Abstract

Balance impairments can affect walking ability and, consequently, limit physical activity level (PAL). This investigation in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) may help unravel factors limiting PAL and identify new rehabilitation strategies to improve mobility in these patients. Eighteen FSHD patients (10 males; mean age: 36.33 years) and twenty-three age- and sex-matched healthy controls (HC) were recruited. Balance was assessed using the Mini-BEST and Four Step Square test (FSST), while PAL was measured with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Gait performance during usual walking (UW), fast walking (FW), and dual-task walking (DT) was evaluated using an inertial sensor (BTS G-Walk). Gait speed (GS), stance time (ST), gait cycle (GC), stride length (SL), pitch and roll angles were considered. Correlations between gait parameters and Mini-BEST were performed in patients, while between PAL, GS, and SL were assessed in both groups. Compared to HC, patients showed lower PAL, Mini-BEST scores and longer FSST times. As group effect, patients exhibited major ST, GC, and roll angle. In the interaction between group and walking condition, during FW patients showed reduced GS and prolonged GC, while no differences were observed in UW and DT. Altered gait parameters, except roll angle, were associated with Mini-BEST, while PAL correlated with gait parameters only in HC. Balance resulted associated with impaired gait parameters in FSHD. The association between balance and gait deficits emerging during FW indicate balance impairment as an element discouraging patients from engaging in physically demanding tasks, plausibly decreasing PAL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD, OMIM #158900) is one of the most common genetically determined muscular dystrophies, second only to Duchenne muscular dystrophy and myotonic dystrophy type 1, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 1:15,000 to 1:20,0001. Its clinical presentation is characterized by progressive asymmetric muscle wasting and fat infiltration, primarily affecting the facial, shoulder, and upper body muscles2, but lower limb may also be involved3, with approximately 20% of patients eventually requiring a wheelchair4. Together with reduced aerobic fitness5,6, pronounced fatigue7, and decreased muscle strength8, gait impairments are among the most significant functional limitations which may derive from the condition9,10.

Specific aspects of gait kinematics in FSHD have been explored. For instance, Alphonsa et al.11 analyzed spatiotemporal gait parameters during single-task and dual-task walking in 9 FSHD patients, reporting reduced cadence and velocity compared to healthy controls (HC), without significant differences between single-task and dual-task conditions. Similarly, Gambelli et al.12 identified lower velocity and shorter step length in 8 FSHD patients, noting that individuals with severe tibialis anterior muscle weakness exhibited increased foot drop and greater variability in minimum toe clearance. These findings indicate the multifaceted nature of gait impairments in FSHD. However, the association between balance, an essential function influencing walking capability across various pathological contexts13,14,15,16, and gait kinematic remains poorly studied. Balance impairment in FSHD would stem mainly from trunk muscle wasting and fat infiltration17. Of note, a study by Aprile et al.18 conducted on a group of 16 FSHD patients, suggested that impairment of static balance leads to reduced performance in brief walking distances. However, a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of balance deficits on gait should go beyond brief, self-paced walking. In real-life scenarios, to adapt to the surrounding environment, it may be necessary, for instance, to increase walking speed or walk in contexts with distractions that divert attention from the motor task; situations that, in pathological conditions, can become challenging. Although conducted in a laboratory setting, analysing the presence of deficits under such conditions (walking at a sustained speed or with a cognitive load) and their relationship with balance could provide valuable insights into disease related impairments, offering new perspectives for targeted rehabilitation aimed at improving locomotion.

Due to its key role in mobility, gait function is strictly linked to physical activity level (PAL), a critical determinant of health19,20 and disease outcomes21. Importantly, physical activity (PA), defined as any movement that increases caloric expenditure beyond resting energy levels22, not only reduces the risk of chronic diseases23 but also has a significant impact on physical efficiency. This effect has been observed across various populations, including healthy individuals at different life stages24,25, as well as in diverse patient cohorts26,27,28. Noteworthy, a retrospective study involving 368 FSHD patients found that a higher PAL during youth, before disease onset, was associated with less severe clinical outcomes later in life29, observation which would indicate that maintaining a high PAL may confer benefits even after the disease is established. Despite this, PAL is underexplored in FSHD. To date, in author’s knowledge, only one study has compared PAL between FSHD patients and a healthy cohort, reporting lower levels in the patients30. The fundamental role of preserving walking ability in enhancing PAL has been highlighted by studies on Parkinson’s disease31, post-stroke populations32, and older adults33. Furthermore, associations between gait kinematic parameters and PAL have been observed in older adults34,35,36 and in Parkinson’s disease patients37, while no study has investigated this relationship in FSHD. In light of such a close relationship, it seems plausible that balance impairments limiting walking ability may, as a consequence, lead to an overall decline in PAL. Exploring the interplay between balance, gait, and PAL in FSHD is crucial not only for a better understanding of disease-related consequences, but also to provide new insights which could guide the development of targeted interventions to improve mobility, foster an active lifestyle, and ultimately preserve patients’ physical efficiency. Hence, the purpose of the present study is to evaluate balance, gait kinematics, and PAL in FSHD patients, analysing associations between these domains and comparing the results with a HC group. We hypothesize that FSHD patients exhibit reduced balance and impaired gait performance compared to HC, with a significant association between the two domains. Moreover, we expect PAL to be lower in the FSHD group and significantly associated with gait parameters in both groups.

Methods

Study design

We performed a single-centre observational cross-sectional controlled study including patients with FSHD and HC. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki; it was approved by the Lombardy Territorial Ethics Committee 6, protocol number 0006176/24, and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The reporting was performed following the STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist38.

Participants

FSHD patients were recruited from the outpatients of the CRIAMS Sport Medicine Centre, Voghera (Italy). The recruitment period lasted from 05/2024 to 12/2024. Evaluations of balance and gait performance were carried out in a dedicated analysis laboratory at the CRIAMS Sport Medicine Centre. Participants, consecutively recruited, were enrolled in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: clinical and genetic diagnosis of FSHD, enrolment in the Italian National Register for FSHD, and maintained ability to walk independently without any support. Exclusion criteria were as follows: being wheelchair-bound at the time of selection, use of corticosteroids, cardiac or respiratory dysfunctions, psychological or psychiatric disorders, major osteoarticular dysfunctions. Patients were categorized into four clinical groups based on the Complete Clinical Evaluation form39, which classifies individuals as follows: category A, with facial and scapular girdle muscle weakness; category B, with muscle weakness confined to either the scapular girdle or facial muscles; category C, asymptomatic individuals; and category D, displaying a myopathic phenotype with clinical features inconsistent with the canonical FSHD presentation. Additionally, a HC group consisting of sex- and age-matched subjects was enrolled from the local community for comparison.

Gait, balance and physical activity level assessments

Gait was assessed during 3 conditions: (I) usual walking (UW): subjects were asked to walk at their self-selected comfortable speed; (II) fast walking (FW): subjects were asked to walk to their maximum speed, not running; (III) cognitive dual task (DT): subjects were asked to walk while performing a verbal fluency task. In each condition, subjects walked back and forth a 20 m path for 1 min, having a 5 min rest period among the tasks. Each gait task was performed once, with the order randomized. Gait parameters were measured using a wearable inertial device (G-Walk, BTS Bioengineering, Italy), an instrument with demonstrated reliability compared to gold standard gait analysis methods40, previously used for similar investigations in various cohorts41,42. This device is composed of a triaxial accelerometer (16 bit/axes) with a sensitivity set at ± 2 g, a triaxial gyroscope (16 bit/axes) with a sensitivity set at ± 2000°/s and a triaxial magnetometer (13 bit, ± 1.200 µT). According to manufacturer instructions, the sensor was positioned below the line that connects the two dimples of Venus-lumbosacral passage, which corresponds to S1–S2 vertebrae, by means of an elastic band. All data were acquired at a frequency of 100 Hz and were transmitted by Bluetooth to a notebook and processed using the BTS G-Studio software (BTS Bioengineering, Italy). The BTS G-Studio software, allowed to obtain a set of gait parameters from which the following were analysed: gait speed (GS, expressed in m/s), stance time (ST, expressed in s), gait cycle (GC, expressed in s), stride length (SL, expressed as % of height), roll trunk angle and pitch trunk angle (expressed in degrees (˚)). Of note, the GS parameter took into account the time required to change gait direction. For each task, the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Moreover, for each of these parameters a coefficient of variability (CV%=SD/mean×100) was also calculated. Given the potential asymmetric muscle involvement in FSHD43, the analysis of ST, GC, and SL were conducted separately for the right and left sides to verify the presence of potential asymmetries. Similarly, for pitch and roll angles, the data referring to the trunk angle related to the support of the left foot and right foot were analysed distinctly.

Balance and dynamic stability were assessed by means of the Mini-Balance Evaluation System Test (Mini-BEST)44, and the Four-Square Step Test (FSST)45, respectively.

Finally, PAL was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ; long form, covering the last seven days), which, in its short form, has previously been used to evaluate PAL in hereditary neuromuscular diseases46. However, in the present study, we opted for the long form as it provides a more detailed assessment47. To further improve the accuracy of the reported data, the questionnaire was administered as an interview by a trained researcher (VQ)48.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-squared test was used to assess gender differences between the two subject groups. The normality and homogeneity of variances were analysed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene’s test, respectively. A 2 (HC and FSHD) x 3 (UW, FW and DT conditions) x 2 (left and right side) repeated-measure ANOVA was used to compare ST, GC, trunk pitch and roll angles. The same ANOVA was used to compare the SL (expressed as % of subject height) and the ST, GC and SL coefficients of variability after being transformed with the arcsin function to account for the non-normal distribution of the percentage values. A 2 (HC and FSHD) x 3 (UW, FW and DT conditions) repeated-measure ANOVA was used to compare the GS and its coefficients of variability after being transformed with the arcsin function. When Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. For all ANOVAs, the post-hoc test analysis was done with the Tukey’s HSD test. The Mini-BEST score, FSST score and IPAQ score were compared between the two subject groups by the Mann-Whitney test. The correlation between gait parameters and the Mini-BEST test was evaluated in the patient group. Moreover, the correlation between PAL and kinematic parameters, previously shown to be associated with it (GS and SL)34,35,36,37, was assessed in both groups. The goodness of the fit was estimated by the Pearson’s r coefficient and the significance of r noted. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JASP (V. 0.18.1, Jasp Team 2023).

Results

Participants

Forty-one subjects participated in the study, of which 18 FSHD patients and 23 HC. Among the patients, none reported hearing or visual impairments, common non-motor FSHD symptoms49. The two groups were similar for age, gender distribution, and height (m). In the comparison of PAL, patients showed significantly lower metabolic equivalent of task (MET) values compared to the control group. Data are summarized in Table 1.

Gait and balance assessment

The mean gait parameters calculated across the two subject groups under the different walking conditions are reported in Fig. 1.

Gait parameters. (panel A) Mean gait speed of the HC (white columns) and FSHD subjects (grey columns) under the three walking conditions: UW, FW, and DT. There was no difference between the two groups of subjects except for the gait speed under FW condition. In panels from B to F the stance time (panel B), gait cycle (panel C), stride length (panel D) and pitch (panel E) and roll trunk angle (panel F) were reported for both body side (left: white and dark grey columns, right: light grey and striped columns) and both groups of subjects (HC: white and light grey, FSHD: dark grey and striped columns) under the three walking conditions. There was a significant difference between the two groups only for the gait cycle (panel C) under FW condition. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). DT, dual tasking; FSHD, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy; FW, fast walking; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; UW, usual walking; °, degree; m, meters; s, seconds.

Gait speed

All walking conditions collapsed, there was no difference in the GS (Fig. 1, panel A) between HC and FSHD subjects (F (1,39) = 1.14, p = 0.29), but there was a significant main effect of walking conditions (F (1.5,58.6) = 210.5, p < 0.001) and a significant interaction between group and walking conditions (F (1.5,58.6) = 7.75, p < 0.01). During the FW the GS was greater than during UW and DT for both HC and FSHD (post-hoc, p < 0.001 for all comparisons), while there was no difference in GS between UW and DT for both subject groups (post-hoc, p > 0.2 for both comparisons). There was no difference in the GS between HC and FSHD under UW (post-hoc, p = 1.0) and DT (post-hoc, p = 0.99). Under FW, instead, the FSHD GS was lower than that of HC (post-hoc, p < 0.05).

Stance time

For the ST (Fig. 1, panel B) there was a significant main effect of the walking condition (F (1.4,54.77) = 135.9, p < 0.001), of the body side (F (1,39) = 8.8, p < 0.01) and a significant difference between the two groups of subjects (FSHD > HC, F (1,39) = 21.8, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant interaction between group and walking conditions (F (1.4,54.77) = 3.2, p = 0.07), group and body side (F (1,39) = 2.47, p = 0.12), group, walking conditions and body side (F (1.56,60.89) = 0.065, p = 0.89).

Gait cycle

There was a significant difference in the GC (Fig. 1, panel C) between HC and FSHD (FSHD > HC, F (1,39) = 25.5, p < 0.001), and between walking conditions (F (1.58,78) = 1.33, p < 0.001). There was no difference in the GC between left and right leg (F (1,39) = 0.76, p = 0.39). A significant interaction was present between walking conditions and subject group (F (1.58,78) = 4.37, p < 0.05), while no interaction was observed between group and body side (F (1,39) = 0.2, p = 0.65) and between group, walking conditions and body side (F (1.42,55.56) = 0.09, p = 0.85). In the FW condition the GC of the FSHD subjects was greater than that observed for the HC (post-hoc, p < 0.001 for all comparisons), whereas only a tendency to increase GC in FSHD subjects compared to healthy subjects was observed in the UW (post-hoc, p = 0.05 for the left side and p = 0.049 for the right side) and DT conditions (post-hoc, p = 0.047 for the left side and p = 0.055 for the right side).

Stride length

The stride length (Fig. 1, panel D) was not different between HC and FSHD all conditions collapsed (F (1,39) = 2.39, p = 0.13), nor was there a difference between body sides (F (1,39) = 0.02, p = 0.87). There was only a significant difference between walking conditions (F (1.45,56.47) = 104.5, p < 0.001). No significant interaction was present between walking conditions and subject group (F (1.45,56.47) = 0.56, p = 0.52), between body side and subject group (F (1,39) = 0.005, p = 0.94) and between walking conditions, body side and subject group (F (1.11,43.48) = 0.11, p = 0.77).

Trunk angles

The pitch trunk angle (Fig. 1, panel E) was not different between HC and FSHD all condition collapsed (F (1,39) = 2.61, p = 0.11) while a significant difference between the two groups was observed for the roll angle (Fig. 1, panel F, FSHD > HC, F (1,39) = 8.6, p < 0.01). For both the trunk angles there was a significant difference between walking conditions (pitch: F (1.6,62.35) = 28.5, p < 0.001; roll: F (1.93,75.32) = 8.53, p < 0.001), while no difference was observed between body sides (pitch: F (1,39) = 1.27, p = 0.27; roll: F (1,39) = 0.19, p = 0.66). For both angles, no significant interaction was present between walking conditions and subject group (pitch: F (1.6,62.35) = 0.41, p = 0.62; roll: F (1.93,75.32) = 0.12, p = 0.88), between body side and subject group (pitch: F (1,39) = 0.002, p = 0.96; roll: F (1,39) = 0.005, p = 0.94) and between walking conditions, body side and subject group (pitch: F (1.18,46.05) = 0.17, p = 0.73; roll: F (1.29,50.19) = 2.25, p = 0.13).

Coefficients of variability

The mean coefficients of variability calculated across the two subject groups under the different walking conditions for gait speed, stance time, gait cycle and stride length were reported in Fig. 2. All conditions collapsed, there was no difference in the coefficients of variability between the two groups for any of the parameters considered: GS (F (1,39) = 0.04, p = 0.84), ST (F (1,39) = 0.0002, p = 0.99), GC (F (1,39) = 0.36, p = 0.55) and SL (F (1,39) = 0.65, p = 0.42).

Variability coefficients calculated for gait speed (panel A), stance time (panel B), gait cycle (panel C) and stride length (panel D) under the three walking conditions: UW, FW and DT. In each panel the variability coefficients were reported for both HC (white and light grey) and FSHD (dark grey and striped columns) and for both body side (left: white and dark grey columns, right: light grey and striped columns) except for the gait speed. There was no difference between the two groups. DT, dual tasking; FSHD, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy; FW, fast walking; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; UW, usual walking.

Balance

In Fig. 3 the mean Mini-Best score (panel A) and the mean completion time of the Four-Square Step test (B) were reported for both HC and FSHD group. Regarding balance performance, FSHD patients showed a significantly lower score in the Mini-BEST Test (p < 0.001) and performed worse in the FSST, as indicated by a longer completion time (p < 0.001), compared to HC.

Mini-BEST score (panel A) and time to complete the Four-Square Step test (panel B). White columns refer to HC, grey columns to FSHD subjects. The FSHD subjects perform worse than healthy subjects in the Mini-BEST test and took more time to complete the Four-Square Step test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (***, p < 0.001). FSHD, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; s, seconds.

Correlation analysis

The results of the correlations between gait parameters and the Mini-BEST test are summarized in Table 2. Due to the similarity between UW and DT conditions, DT was not considered for the correlation analysis. Only the gait parameters related to the right side were considered, since as previously seen, there are no significant differences in these parameters between the two body sides. In the FSHD group, several gait parameters showed significant correlations with the Mini-BEST score, including GC during both UW and FW, ST during both UW and FW, and GS during FW.

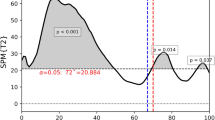

In Fig. 4 the PAL score was plotted against the GS (panel A) and SL (panel B) under UW and FW conditions for both HC and FSHD. In the HC group, GS and SL, both in UW and FW conditions, positively correlated with PAL (GS during UW: Pearson’s r = 0.67-, p < 0.001, GS during FW: Pearson’s r = 0.63, p = 0.001; SL during UW: Pearson’s r = 0.64, p < 0.001, SL during FW: Pearson’s r = 0.75, p < 0.001). Conversely, none of these correlations were significant in the FSHD group.

Graphical representations of the correlation analysis between gait speed and PAL (panel A) and between stride length and PAL (panel B) under UW and FW conditions in both FSHD and HC groups. Each symbol corresponds to a subject. FSHD, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy; FW, fast walking; HC, healthy controls; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; PAL, physical activity level; UW, usual walking; °, degree; m, meters; s, seconds.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the relationship between balance, gait, and PAL in patients with FSHD. The results reveal significant differences between the groups across all domains investigated. PAL was significantly lower in patients with FSHD, a finding consistent with that reported by Vera et al.30 on 11 FSHD patients, who suggested that such reduction might impact resting metabolic rate. Regarding balance, patients scored significantly lower in the Mini-BEST test and had longer times on the FSST. In author’s knowledge, this is the first study to implement these tests in patients with FSHD, making direct comparisons with other studies difficult. However, the results appear to be consistent with those obtained in other FSHD cohorts in which balance impairments have been observed by means of instrumental investigations17,18. Importantly, our results suggest that the Mini-BEST test and FSST may serve as valid tools for monitoring balance and dynamic stability in individuals with FSHD. This is relevant in clinical settings and rehabilitation contexts, where the need for repeated evaluations benefits from the use of accessible and low-cost tools.

Interaction between group and walking condition

This is the first study to examine gait under three different conditions (UW, FW, and DT) within the same cohort of FSHD patients, offering a comprehensive perspective on gait variations that arise in contexts beyond spontaneous walking. The obtained data revealed differences compared to HC and only partial consistency with the existing literature. Considering the interaction of group and specific walking conditions, during UW patients with FSHD exhibited behaviour largely comparable to that of HC, with no significant differences observed between the groups for any of the parameters investigated, despite a trend toward significance for a longer GC (Fig. 1). This observation contrasts with data reported in other studies, which found a lower GS9,10,11,12,50 and reduced SL10 in patients during UW. Several factors may contribute to this discrepancy. For instance, the variability inherent in examinations conducted on relatively small groups (in all these studies, the sample size was smaller than ours) may lead to differing results. Additionally, the wide clinical variability of FSHD51 could lead to different findings depending on the cohort analyzed. The latter hypothesis would be consistent with studies reporting that some gait-related parameters (step length, forward stability margins during a trailing step, toe clearance, trunk and hip flexion) may vary among patients with different levels of impairment or clinical manifestations12,50; however, once again, the small sample sizes analysed in these studies (4 severe tibialis anterior weakness vs. 4 mild tibialis anterior weakness patients, and 4 mildly affected vs. 6 moderately affected patients, respectively) necessitate interpreting the findings with caution. In summary, the discrepancy between the data obtained in this study and the existing literature appears to reflect the well-known clinical variability of the disease and underscores the need for further studies involving larger and more homogeneous cohorts that allow for stratification by potential confounding factors.

In the FW, a reduction in GS and a longer GC compared to HC were observed (Fig. 1). To the author’s knowledge, the only other study that evaluated FW in FSHD patients is Rijken et al.52, in which data from the FW and UW within the same FSHD group were used to investigate gait propulsion and ankle plantar flexor weakness. Unfortunately, the lack of a HC group limits the comparability of the results. Nevertheless, our data indicate that subjecting patients to a more physically demanding walking condition, such as FW, may serve as an effective approach to uncover subtle kinematic alterations that may remain undetected during UW.

Finally, our results regarding DT are consistent with the only other study that evaluated it11 which, despite the different cognitive task employed (serial 7’s subtraction vs. verbal fluency), reported no differences between UW and DT in FSHD for the investigated parameters (GS and cadence).

In summary, the results obtained in the present cohort of FSHD patients suggest that FW is the gait modality that best differentiates between FSHD patients and HC, whereas UW and DT conditions yield similar outcomes across the two groups.

Group effect

Considering the group effect, collapsing all walking conditions, two additional differences emerge in patients compared to HC: greater ST and roll angle. Moreover, a longer GC, already observed in FW, is confirmed. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate ST in FSHD, which prevents direct comparisons. However, an increase in ST is a well-known hallmark of unfavourable locomotion patterns, observed in several cohorts of patients with gait deficits53,54,55. Noteworthy, an extended ST coupled with lower GS (as observed in the FW condition) has been reported in other conditions with gait impairments, such as cervical dystonia and ataxia13,56. In these cases, patients use this strategy to compensate for deficits in dynamic postural control by shortening the swing phase and lengthening the stance phase. Applied to our cohort, such strategy would align with the observed balance and dynamic stability deficits, as well as the negative association between ST and the Mini-BEST score found in both UW and FW conditions (Table 2).

Regarding the roll angle, our results align only partially with the existing literature. In fact, Iosa et al.10 reported wider and less symmetrical oscillations in both roll and pitch angles compared to HC. Another study by Rijken et al.50 found greater trunk and hip flexion during a trailing step, whereas trunk stability appeared normal during level walking. Overall, once again, the need for additional characterization elements to identify specific disease manifestation patterns on gait function becomes evident. Indeed, although all the exposed data seem to converge towards the well-known trunk muscles impairment17, the underlying reasons for the observed different alterations remain unclear. Based on the literature, it seems plausible that the heterogeneity in the distribution of fat infiltration in the trunk muscles57 may underlie the different alterations. However, future studies will be needed to clarify the specific consequences of the degree of impairment and the mapping of muscle involvement on trunk control during gait.

Instead, the increased GC appears to be consistent with the findings of Rijken et al.50, who identified a markedly longer step time in patients and seems also consistent with the reduced GS observed in the FW condition.

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis revealed that, in the FSHD group, all gait parameters (except for roll angle) showing a difference compared to HC, both for the group effect and for the interaction between group and gait condition, were significantly associated with the Mini-BEST score (Table 2). The negative association with GC and ST, observed during both UW and FW, appears to confirm the critical role of balance in influencing these parameters, as previously indicated by observations in post-stroke patients58 and those with Parkinson’s disease59. Moreover, the positive association with GS during FW seems in line with the findings of Findling et al.60, who reported that patients with multiple sclerosis compensate for reduced balance abilities by decreasing their GS. Overall, the present findings highlight that in FSHD, like other gait-impaired populations61,62,63,64, there is a clear connection between gait and balance. This suggests that rehabilitation interventions should address both domains to optimize functional improvements. Furthermore, from a methodological perspective, it indicates the utility of the Mini-BEST in identifying balance impairments that impact gait alterations, as already observed in other patient cohorts13,65.

Interestingly, the results from the correlation analysis between gait parameters and PAL in the HC group appear to confirm the well-established relationship between the two domains66,67. In fact, in line with previous findings34,35,36,37,68 GS and SL were positively and significantly associated with PAL. Conversely, in the FSHD group, we did not observe any significant association between gait parameters and PAL (Fig. 4). The underlying reason for this discrepancy is not clear and opens the door to new research questions. On one hand, the cross-referencing of comparative and correlational data may suggest that the significant difference observed for the GS parameter could underlie the lack of association in patients. However, also SL, which is comparable between the two groups, shows association only in the HC group, thereby challenging this interpretation.

Noteworthy, patients appear to exhibit higher PAL variability, as appreciable in Fig. 4 and reflected in the CV% calculated from the whole groups mean and SD values (HC: 11.19%; FSHD: 64.56%). In contrast, the CV% of gait parameters were statistically similar between the two groups across all conditions investigated (Fig. 2). This apparent different variability between the two datasets could hinder the identification of a significant association. Interestingly, a higher CV% in the PAL of FSHD patients compared to the HC group is also suggested by data from another study that measured it30. In such work, the PAL, quantified using the Activity Metabolic Index Score from the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire69, showed a mean value of 25.1 ± 32.1 SD for the FSHD group, while for the HC group it was 181.6 ± 148 SD, from which a CV% of 127.9% for the patients and 81.6% for the HC can be calculated. Obviously, the estimation of the CV% based on whole groups mean and SD lacks statistical validity. However, the higher value observed in both studies could suggest a new research perspective worthy of further exploration in a dedicated work.

Considerations on PAL and walking conditions

The results observed in the various walking conditions may provide valuable insights into the factors contributing to the observed lower PAL in patients. Specifically, the similarities between groups during UW and the differences during FW, a modality requiring greater physical effort, suggest that the reduced PAL in patients may primarily result from a decrease in moderate-to-vigorous PA, while low-intensity activities, such as self-paced walking, may be better preserved. Since the parameters altered during FW, namely GS and GC, are significantly associated with the Mini-BEST score (Table 2), our data suggest that balance impairments could discourage engagement in high-effort PA. Therefore, a rehabilitation program focused on improving balance and gait could play a crucial role in enabling patients to perform activities requiring greater physical effort, potentially increasing their PAL. For instance, the FW, used here for kinematic analysis, can also serve as an effective exercise to enhance aerobic fitness70,71, a component typically deficient in FSHD patients5,72,73. Building on these observations, exploring the impact of balance enhancement on patients’ ability to engage in a structured training regimen, such as regular FW practice, could represent a promising future research direction. This approach could help elevate patients’ PAL and improve physical efficiency.

Limitations and future directions

This study has some limitations. First, future studies with larger cohorts will be important to confirm or disprove the reported findings. In particular, it would be crucial to assess whether variations in the clinical category defined by the CCEF are associated with different gait, balance, and PAL characteristics. This analysis, which was not possible in the present study due to the limited representation of categories B, C, and D, would provide important information on the effects of the disease and for the development of more specific rehabilitation programs. Moreover, future studies should adopt an objective quantification of PAL, rather than a self-assessed measure, to avoid potential perceptual biases. Objective quantification of PAL would be a fundamental prerequisite to shed light on the wide variability suggested by the data from this study and that by Vera et al.30 and, if confirmed, to evaluate the factors that determine it. Moreover, considering that FSHD predominantly affects upper limb function and that impairments in the upper extremities can influence both gait74 and balance function75, it is important that future research explores the interplay between upper limb deficits and balance/gait performance, along with their consequent effects on PAL. Such investigations will be crucial for developing more global and effective rehabilitation approaches for this patient population.

Conclusion

Our results show that all gait deficits, except for the roll angle, are significantly associated with balance capability. This observation suggests the importance of developing rehabilitation programs that target both balance and gait functions as the most effective approach to enhance mobility. Notably, the PAL of FSHD patients is significantly lower than that of HC and, unlike the latter, is not associated with any kinematic gait parameters. Based on the observation that the deficits emerging during FW are associated with balance, future interventional studies should investigate whether targeted rehabilitation programs aimed at improving both balance and gait can help patients engage in physically demanding activities, thereby effectively promoting an increase in PAL.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hamel, J. et al. Patient-reported symptoms in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (PRISM-FSHD). Neurology 93 (12), e1180–e1192. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000008123 (2019).

Vera, K. A., McConville, M., Kyba, M. & Keller-Ross, M. L. Sarcopenic obesity in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Front. Physiol. 11, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.01008 (2020).

Zheng, F. et al. Age at onset mediates genetic impact on disease severity in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Brain 148 (2), 613–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awae309 (2024).

Voet, N. B., Bleijenberg, G., Padberg, G. W., van Engelen, B. G. & Geurts, A. C. Effect of aerobic exercise training and cognitive behavioural therapy on reduction of chronic fatigue in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: Protocol of the FACTS-2-FSHD trial. BMC Neurol. 10, 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-10-56 (2010).

Vera, K. A. et al. Exercise intolerance in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Med Sci. Sports Exerc. 54 (6), 887–895. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002882 (2022).

Crisafulli, O. et al. Bioimpedance analysis of fat free mass and its subcomponents and relative associations with maximal oxygen consumption in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 125 (1), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-024-05581-5 (2024).

Schipper, K., Bakker, M. & Abma, T. Fatigue in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: A qualitative study of people’s experiences. Disabil. Rehabil. 39 (18), 1840–1846. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1212109 (2017).

Wilson, V. D. et al. Muscle strength, quantity and quality and muscle fat quantity and their association with oxidative stress in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: Effect of antioxidant supplementation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 219, 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.04.001 (2024).

Iosa, M. et al. Mobility assessment of patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 22 (10), 1074–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.07.013 (2007).

Iosa, M. et al. Control of the upper body movements during level walking in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Gait Posture. 31 (1), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.08.247 (2010).

Alphonsa, S., Wuebbles, R., Jones, T., Pavilionis, P. & Murray, N. Spatio-temporal gait differences in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy during single and dual task overground walking: A pilot study. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 8 (2), 166–175 (2022).

Gambelli, C. N. et al. The effect of tibialis anterior weakness on foot drop and toe clearance in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 102, 105899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2023.105899 (2023).

Crisafulli, O. et al. Dual task gait deteriorates gait performance in cervical dystonia patients: A pilot study. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 128 (11), 1677–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02393-1 (2021).

Costa, T. M. et al. Gait and posture are correlated domains in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 775, 136537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136537 (2022).

Alizadehsaravi, L., Bruijn, S. M., Muijres, W., Koster, R. A. J. & van Dieën, J. H. Improvement in gait stability in older adults after ten sessions of standing balance training. PLoS ONE. 17 (7), e0242115. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242115 (2022).

Cho, J., Ha, S., Lee, J., Kim, M. & Kim, H. Stroke walking and balance characteristics via principal component analysis. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 10465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60943-5 (2024).

Rijken, N. H., van Engelen, B. G., de Rooy, J. W., Geurts, A. C. & Weerdesteyn, V. Trunk muscle involvement is most critical for the loss of balance control in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 29 (8), 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.07.008 (2014).

Aprile, I. et al. Balance and walking in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: Multiperspective assessment. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 48 (3), 393–402 (2012).

Bravata, D. M. et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review. JAMA 298 (19), 2296–2304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.19.2296 (2007).

Bull, F. C. et al. World health organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54 (24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Garcia, L. et al. Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes: A dose-response meta-analysis of large prospective studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 57 (15), 979–989. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-105669 (2023).

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E. & Christenson, G. M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 100 (2), 126–131 (1985).

Ng, K. S., Lian, J., Huang, F., Yu, Y. & Vardhanabhuti, V. Association between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and chronic disease risk in adults and elderly: Insights from the UK biobank study. Front. Physiol. 15, 1465168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1465168 (2024).

Marzetti, E. et al. Physical activity and exercise as countermeasures to physical frailty and sarcopenia. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 29 (1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0705-4 (2017).

Wang, C., Tian, Z., Hu, Y. & Luo, Q. Physical activity interventions for cardiopulmonary fitness in obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 23 (1), 558. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04381-8 (2023).

Gothe, N. P. & Bourbeau, K. Associations between physical activity intensities and physical function in stroke survivors. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 99 (8), 733–738. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001410 (2020).

Rooney, S. et al. Physical activity is associated with neuromuscular and physical function in patients with multiple sclerosis independent of disease severity. Disabil. Rehabil. 43 (5), 632–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1634768 (2021).

Iijima, H. et al. Relationship between pedometer-based physical activity and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A cross-sectional study. Arch Phys. Med Rehabil. 98 (7), 1382–1388e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.12.021 (2017).

Bettio, C. et al. Physical activity practiced at a young age is associated with a less severe subsequent clinical presentation in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25 (1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-07150-x (2024).

Vera, K., McConville, M., Kyba, M. & Keller-Ross, M. Resting metabolic rate in adults with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 46 (9), 1058–1064. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-1119 (2021).

Domingues, V. L., Pompeu, J. E., de Freitas, T. B., Polese, J. & Torriani-Pasin, C. Physical activity level is associated with gait performance and five times sit-to-stand in parkinson’s disease individuals. Acta Neurol. Belg. 122 (1), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-021-01824-w (2022).

Fini, N. A., Bernhardt, J. & Holland, A. E. Low gait speed is associated with low physical activity and high sedentary time following stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 43 (14), 2001–2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1691273 (2021).

Egerton, T., Paterson, K. & Helbostad, J. L. The association between gait characteristics and ambulatory physical activity in older people: A cross-sectional and longitudinal observational study using generation 100 data. J. Aging Phys. Act. 25 (1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2015-0252 (2017).

Rosengren, K. S., McAuley, E. & Mihalko, S. L. Gait adjustments in older adults: Activity and efficacy influences. Psychol. Aging. 13 (3), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.13.3.375 (1998).

Porto, J. M., Pieruccini-Faria, F., Bandeira, A. C. L., Bôdo, J. S. & Abreu, D.C.C. Physical activity components associated with gait parameters in community-dwelling older adults. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 38, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.11.064 (2024).

Krell-Roesch, J. et al. Self-reported physical activity and gait in older adults without dementia: A longitudinal study. Health Sci. Rep. 7 (11), e70108. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.70108 (2024).

Bastos, P., Meira, B., Mendonça, M. & Barbosa, R. Distinct gait dimensions are modulated by physical activity in Parkinson’s disease patients. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 129 (7), 879–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-022-02501-9 (2022).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61 (4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 (2008).

Ricci, G. et al. A novel clinical tool to classify facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy phenotypes. J. Neurol. 263 (6), 1204–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8123-2 (2016).

De Ridder, R. et al. Concurrent validity of a commercial wireless trunk triaxial accelerometer system for gait analysis. J. Sport Rehabil. 28 (6), jsr.2018–0295. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2018-0295 (2019).

Familiari, F. et al. Shoulder Brace has no detrimental effect on basic spatio-temporal gait parameters and functional mobility after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Gait Posture. 107, 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.10.005 (2024).

Leonardi, L. et al. A wearable proprioceptive stabilizer for rehabilitation of limb and gait ataxia in hereditary cerebellar ataxias: A pilot open-labeled study. Neurol. Sci. 38 (3), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2800-x (2017).

Aguirre, A. S. et al. Treatment of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD): A systematic review. Cureus 15 (6), e39903. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39903 (2023).

Godi, M. et al. Comparison of reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Mini-BESTest and Berg balance scale in patients with balance disorders. Phys. Ther. 93 (2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120171 (2013).

Moore, M. & Barker, K. The validity and reliability of the four square step test in different adult populations: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 6 (1), 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0577-5 (2017).

Andries, A., Van Walsem, M. R., Ørstavik, K. & Frich, J. C. Functional ability and physical activity in hereditary neuromuscular diseases. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 9 (3), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-210677 (2022).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35 (8), 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000078924.61453.fb (2003).

Van Dyck, D., Cardon, G., Deforche, B. & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. IPAQ interview version: Convergent validity with accelerometers and comparison of physical activity and sedentary time levels with the self-administered version. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 55 (7–8), 776–786 (2015).

Padberg, G. W. et al. On the significance of retinal vascular disease and hearing loss in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 2, S73–80 (1995).

Rijken, N. H., van Engelen, B. G., Geurts, A. C. & Weerdesteyn, V. Dynamic stability during level walking and obstacle crossing in persons with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Gait Posture. 42 (3), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.06.005 (2015).

Salsi, V., Vattemi, G. N. A. & Tupler, R. G. The FSHD jigsaw: Are we placing the tiles in the right position? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 36 (5), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1097/wco.0000000000001176 (2023).

Rijken, N. H., van Engelen, B. G., de Rooy, J. W., Weerdesteyn, V. & Geurts, A. C. Gait propulsion in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and ankle plantarflexor weakness. Gait Posture. 41 (2), 476–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.11.013 (2015).

Gommans, L. N. M. et al. Prolonged stance phase during walking in intermittent claudication. J. Vasc Surg. 66 (2), 515–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.02.033 (2017).

Farashi, S. Analysis of the stance phase of the gait cycle in parkinson’s disease and its potency for parkinson’s disease discrimination. J. Biomech. 129, 110818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110818 (2021).

Õunpuu, S., Pierz, K., Garibay, E., Acsadi, G. & Wren, T. A. L. Stance and swing phase ankle phenotypes in youth with Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1: An evaluation using comprehensive gait analysis techniques. Gait Posture. 98, 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.09.077 (2022).

Buckley, E., Mazzà, C. & McNeill, A. A systematic review of the gait characteristics associated with cerebellar ataxia. Gait Posture. 60, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.11.024 (2018).

Rijken, N. H. et al. Skeletal muscle imaging in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, pattern and asymmetry of individual muscle involvement. Neuromuscul. Disord. 24 (12), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2014.05.012 (2014).

Nam, H. S., Clancy, C., Smuck, M. & Lansberg, M. G. Insole pressure sensors to assess post-stroke gait. Ann. Rehabil Med. 48 (1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.23064 (2024).

Rennie, L., Opheim, A., Dietrichs, E., Löfgren, N. & Franzén, E. Highly challenging balance and gait training for individuals with parkinson’s disease improves pace, rhythm and variability domains of gait: A secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 35 (2), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215520956503 (2021).

Findling, O. et al. Balance changes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A pilot study comparing the dynamics of the relapse and remitting phases. Front. Neurol. 9, 686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00686 (2018).

Mori, L. et al. Outcome measures in the clinical evaluation of ambulatory Charcot-Marie- tooth 1A subjects. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 55 (1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.23736/s1973-9087.18.05111-0 (2019).

Espinoza-Araneda, J. et al. Postural balance and gait parameters of independent older adults: A sex difference analysis. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (7), 4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074064 (2022).

Karabin, M. J., Sparto, P. J., Rosano, C. & Redfern, M. S. Impact of strength and balance on functional gait assessment performance in older adults. Gait Posture. 91, 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.10.045 (2022).

Bottoni, G. et al. An 8-month adapted motor activity program in a young CMT1A male patient. Front. Physiol. 15, 1347319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1347319 (2024).

Combs, S. A., Diehl, M. D., Filip, J. & Long, E. Short-distance walking speed tests in people with Parkinson disease: Reliability, responsiveness, and validity. Gait Posture. 39 (2), 784–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.10.019 (2014).

Cabell, L., Pienkowski, D., Shapiro, R. & Janura, M. Effect of age and activity level on lower extremity gait dynamics: An introductory study. J. Strength. Cond Res. 27 (6), 1503–1510. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318269f83d (2013).

Ciprandi, D. et al. Study of the association between gait variability and physical activity. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-017-0188-0 (2017).

Karavirta, L. et al. Physical determinants of daily physical activity in older men and women. PLoS ONE. 20 (2), e0314456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314456 (2025).

Richardson, M. T., Leon, A. S., Jacobs, D. R., Jr, Ainsworth, B. E. & Serfass, R. Comprehensive evaluation of the Minnesota leisure time physical activity questionnaire. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47 (3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90008-6 (1994).

Bai, X. et al. Effect of brisk walking on health-related physical fitness balance and life satisfaction among the elderly: A systematic review. Front. Public Health. 9, 829367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.829367 (2022).

Murphy, M., Nevill, A., Neville, C., Biddle, S. & Hardman, A. Accumulating brisk walking for fitness, cardiovascular risk, and psychological health. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 34 (9), 1468–1474. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200209000-00011 (2002).

Crisafulli, O. et al. Maximal oxygen consumption is negatively associated with fat mass in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 21 (8), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080979 (2024).

Crisafulli, O. et al. Analysis of body fluid Distribution, phase angle and its association with maximal oxygen consumption in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: An observational study. Health Sci. Rep. 8 (1), e70335. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.70335 (2025).

Moreno Izco, F. et al. Análisis de la marcha y del movimiento de las extremidades superiores en distrofias musculares [Analysis of gait and movement of upper limbs in muscular dystrophies]. Neurologia. 20(7), 341-348. Spanish. (2005).

Boström, K. J., Dirksen, T., Zentgraf, K. & Wagner, H. The contribution of upper body movements to dynamic balance regulation during challenged locomotion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 26, 12:8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00008 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the patients who participated in the study, and Dr. Matteo Fortunati for his technical and logistical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM-Téléthon), [Grant n° 24420] to GD and by the Ricerca corrente 5×1000-2020 (cod. 090000X121—progetto 08050122) to GMS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oscar Crisafulli: Conceptualization, investigation, data curation, data analysis, methodology, original draft preparation, review and editing. Stefania Sozzi: Data analysis, original draft preparation, review and editing. Venere Quintiero: Investigation; review and editing. Massimo Negro: Investigation; review and editing. Rossella Tupler: Data curation, methodology; review and editing. Stefano Ramat: Investigation, methodology, review and editing. Giulia Maria Stella: Data curation, methodology; review and editing. Micaela Schmid: Data analysis, methodology, review and editing. Giuseppe D’Antona: Conceptualization, project administration, investigation, data curation, data analysis, supervision, methodology, original draft preparation, review and editing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki; it was approved by the Lombardy Territorial Ethics Committee 6, protocol number 0006176/24, and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Crisafulli, O., Sozzi, S., Quintiero, V. et al. Interplay between balance, gait kinematic and physical activity level in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Sci Rep 15, 42973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26924-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26924-y