Abstract

This study develops a novel HIV/AIDS compartmental model that integrates the critical, interconnected challenges of drug resistance emergence from treated individuals, healthcare constraints via a saturating treatment function, and persistent vertical transmission. The objective is to provide a comprehensive mathematical framework for analyzing these complex dynamics and designing effective intervention strategies. Our analysis reveals that treatment saturation can induce a backward bifurcation, complicating disease eradication efforts, while optimal control simulations demonstrate that a combined strategy of enhanced screening, accelerated treatment initiation, and adherence support significantly reduces infection pools and minimizes disease progression compared to isolated interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) remains one of the most significant global public health challenges of our time1. As of 2023, an estimated 39.0 million people were living with HIV globally, and despite progress, the epidemic was responsible for 1.3 million new infections and 630,000 deaths in the preceding year, underscoring its persistent threat2. The advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been a pivotal turning point, transforming HIV from a terminal illness into a manageable chronic condition for many3. However, the long-term success of these programs is critically threatened by a complex interplay of biological and socio-economic factors, including persistent transmission routes, healthcare system constraints, and, crucially, the evolution of drug-resistant viral strains4,5,6. The emergence of drug-resistant HIV represents a formidable obstacle to the long-term success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and global epidemic control. Resistance is an evolutionary process where the virus mutates under the selective pressure of medication, rendering drugs less effective. This process is critically accelerated by incomplete viral suppression, a common consequence of poor patient adherence to complex and lifelong treatment regimens7. On a clinical level, the development of resistance leads to virological failure, marked by a rebound in viral load, a decline in immune function, and an accelerated progression to AIDS, which necessitates a switch to more complex and often more toxic second- or third-line therapies4. The public health threat is magnified by the transmission of these resistant strains, which can severely compromise the efficacy of standard first-line treatments for newly infected individuals, thereby undermining national and global treatment guidelines6. The landscape of resistance is further complicated by the existence of numerous drug-resistant subtypes and the challenge of multidrug resistance, making clinical management increasingly difficult5. Consequently, mathematical models that explicitly incorporate the dynamics of drug resistance are essential tools for evaluating how factors like treatment coverage and healthcare resources influence its spread, and for designing sustainable public health strategies that can preserve the effectiveness of current and future therapies8.

Mathematical modeling has become an indispensable tool for understanding the intricate transmission dynamics of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS, with numerous recent studies demonstrating its utility in analyzing stability and simulating disease spread9,10,11. By translating complex biological and social processes into a system of mathematical equations, models allow researchers to dissect the key drivers of an epidemic, predict its future course, and evaluate the potential impact of various public health interventions, such as optimal control strategies12,13,14,15,16. This quantitative approach is crucial for designing evidence-based strategies that are both effective and resource-efficient. A primary challenge to the long-term control of HIV is the evolution of drug-resistant viral strains, a phenomenon often driven by poor patient adherence or incomplete viral suppression7. The emergence of resistance leads not only to individual treatment failure and disease progression but also to the potential for transmitting these compromised strains to others4,5,6. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of resistance emergence and its spread through the population is critical for developing robust models and sustaining the long-term effectiveness of ART programs.

Recent mathematical modeling efforts by Olaniyi and collaborators have significantly advanced the field of epidemiological dynamics across various diseases. Their work on HIV/AIDS has explored both autonomous systems with vertical transmission and nonlinear treatment17 and, more recently, non-autonomous systems to investigate time-varying, cost-effective intervention strategies18. Beyond HIV, their methodological rigor has been applied to other pathogens, including a stability and intervention analysis of Rift Valley fever19 and a Lyapunov stability and economic evaluation of monkeypox dynamics incorporating vertical transmission20. This group has also demonstrated expertise in modeling complex public health issues beyond infectious diseases, such as substance abuse with real data integration21. A common strength of these studies is their focus on rigorous stability analysis and the evaluation of optimal control measures. However, a review of this body of work reveals a specific gap relevant to the long-term management of HIV: while the models in17,18 effectively address treatment and interventions, they do not explicitly incorporate the critical phenomenon of drug resistance emerging from the treated population. This omission is significant, as drug resistance is a primary obstacle to the sustainability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs. To address this gap, our study develops a novel deterministic compartmental model that uniquely integrates the interconnected dynamics of (i) a saturating treatment function reflecting healthcare constraints, (ii) the emergence of drug resistance from the treated compartment, and (iii) persistent vertical transmission. The novelty of our work lies in this unified framework, which allows for a detailed investigation of how treatment saturation can induce a backward bifurcation a complex behavior with profound implications for disease eradication and facilitates the design of an optimal control strategy that specifically targets the suppression of drug-resistant strains, a challenge not simultaneously tackled in the aforementioned studies. Other mathematical models have been instrumental in exploring HIV dynamics, with studies focusing on local and global stability analysis and the simulation of parameter impacts on disease spread7,9,10. A key feature in many models is the inclusion of vertical transmission; despite successful prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs, an estimated 130,000 new infections occurred in children in 2022, highlighting it as a persistent driver of the epidemic across generations2,22. Another critical real-world factor is the capacity of healthcare systems. As of 2022, approximately 29.8 million of the 39.0 million people living with HIV were on ART, a gap that justifies using a nonlinear, saturating treatment function to model bottlenecks in care that can influence the dynamics of drug resistance2,8. The evolution of drug-resistant strains, driven by factors like incomplete viral suppression, is a central challenge, as maintaining the required >95% adherence level is difficult for many patients4,5,6. To address these multifaceted challenges, Optimal Control Theory (OCT) offers a powerful framework for designing dynamic intervention strategies to minimize infections and mortality12,13,23. Furthermore, bifurcation analysis has been a pivotal tool for uncovering complex behaviors, such as the backward bifurcation phenomenon, which has profound public health implications as it suggests that simply bringing the basic reproduction number below unity may not be sufficient to eradicate the disease24.

The landscape of the HIV/AIDS modeling has expanded considerably to capture increasing epidemiological complexities, including co-infections with diseases like pneumonia, COVID-19, and Hepatitis23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 and demographic structures such as age35. Furthermore, critical individual factors like drug resistance5,7, healthcare constraints via saturating treatment functions8, and vertical transmission22 have been studied. However, a significant gap persists, as these critical dynamics are often explored in isolation. A comprehensive framework that simultaneously integrates the deeply synergistic interplay of drug resistance emergence, treatment saturation, and vertical transmission remains underdeveloped. This is a crucial omission, as these factors are interconnected: treatment saturation can exacerbate selection pressure for drug resistance, while vertical transmission perpetuates the epidemic by creating a continuous pool of individuals who will eventually strain the treatment system.

To address this gap, we propose a novel deterministic compartmental model whose novelty lies in its unified framework that concurrently incorporates the emergence of drug resistance from the treated population, a nonlinear saturating treatment function reflecting healthcare constraints, persistent vertical transmission, and the mitigating effect of media awareness. The primary objectives of this study are twofold: first, to conduct a rigorous qualitative analysis of this comprehensive model, including deriving the basic reproduction number, analyzing equilibrium stability, and investigating bifurcation phenomena; and second, to apply optimal control theory to design a dynamic, multi-pronged intervention strategy. By analyzing how the combined factors induce complex behaviors like backward bifurcation and formulating optimal control strategies to mitigate them, this work provides a significant extension to the literature and a more realistic tool for public health planning.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Model formulation” details the formulation of the mathematical model. Section “Theoretical analysis” presents the qualitative analysis of the model, including its fundamental properties, equilibrium points, and bifurcation analysis. Section “Sensitivity analysis” is dedicated to the sensitivity analysis, where we identify the parameters that most significantly influence disease transmission. Section "Optimal control problem and analysis" formulates the optimal control problem and derives its solution. Section "Numerical simulation results and discussions" provides numerical simulations to illustrate our analytical findings and demonstrate the effectiveness of the optimal control strategies. Finally, Sect. "Conclusions and Future Directions of the Study" offers conclusions and discusses potential directions for future research.

Model formulation

To better understand and control the transmission dynamics of HIV/AIDS, we propose a deterministic compartmental model that integrates key epidemiological and social factors: the development of drug resistance, healthcare system constraints, media-driven awareness, and comprehensive vertical transmission. The total human population, N(t), at any time t is divided into six mutually exclusive compartments: susceptible individuals (S(t)), unaware HIV-infected individuals (\(I_a(t)\)), aware HIV-infected individuals not yet on treatment (\(I_b(t)\)), individuals on ART for drug-sensitive HIV (T(t)), individuals infected with drug-resistant HIV (R(t)), and individuals who have progressed to full-blown AIDS (A(t)) such that the total human population is represented by:

The population is sustained by a constant birth rate, \(\kappa\). However, the inflow into the susceptible class is reduced by vertical transmission, a fraction q of infants born to mothers from any of the infected compartments (\(I_a, I_b, T, R,\) or A) become infected at birth. Consequently, only the remaining fraction of newborns enter the susceptible class. Susceptible individuals become infected through contact with infectious individuals. This transmission process is modulated by a constant media awareness parameter, m, where \(0 \le m < 1\), which reflects the impact of public health campaigns and general awareness in reducing high-risk behaviors, thereby lowering the effective transmission rate. The relative infectiousness of different groups is accounted for by modification factors \(\tau _1, \tau _2, \tau _3,\) and \(\tau _4\). These factors are all assumed to be less than one, reflecting a reduction in transmission compared to the baseline infectiousness of the unaware group (\(I_a\)). Specifically, we assume a hierarchy of infectiousness such that \(1> \tau _1> \tau _2> \tau _3> \tau _4\). This hierarchy represents the combined effects of awareness and disease progression: aware individuals (\(\tau _1\)) are assumed to adopt safer behaviors; treated individuals (\(\tau _2\)) benefit from suppressed viral loads; and individuals with resistant HIV (\(\tau _3\)) or advanced AIDS (\(\tau _4\)) are assumed to have a lower overall contribution to new infections, potentially due to reduced activity levels associated with illness, despite their high viral loads. Upon infection, susceptible individuals move into the \(I_a(t)\) class, which consists of HIV-infected individuals who are unaware of their status. These individuals are a key driver of the epidemic due to potentially higher-risk behaviors. They may be identified through screening at a rate \(\alpha\), transitioning them into the \(I_b(t)\) class. Individuals in \(I_b(t)\) are aware of their HIV-positive status but have not yet started treatment. Crucially, this compartment is also populated by newborns infected through vertical transmission. A fraction q of infants born to mothers from any infected compartment enter this aware class directly, reflecting immediate diagnosis at birth as part of modern PMTCT (Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission) protocols. Unaware individuals who are not detected in time may progress directly to AIDS at rate \(\sigma\). Individuals in \(I_b(t)\), who are aware of their infection, may begin ART at a nonlinear rate \(\frac{\theta I_b}{1 + \rho I_b}\). The denominator term, \(1 + \rho I_b\), captures the phenomenon of treatment saturation, where healthcare system capacity limitations can slow the rate of ART initiation as the number of eligible individuals grows. Those who do not receive treatment in time may progress to AIDS at a rate \(\xi\). Treated individuals move into the T(t) class. Over time, due to factors like poor adherence or incomplete viral suppression, a fraction of these individuals may develop drug resistance, transitioning to the R(t) class at rate \(\omega\). The R(t) compartment represents individuals infected with drug-resistant HIV strains, who may not respond to standard ART and can progress to AIDS at a rate \(\eta\). Individuals in the final stage, A(t), may have originated from the \(I_a, I_b,\) or R compartments. This group experiences an AIDS-induced death rate of \(\delta\). All compartments are also subject to a natural death rate, \(\mu\). In our proposed HIV/AIDS model formulation, we assume that the total human population is variable, and the population is homogeneously mixed. The susceptible individuals acquire HIV/AIDs infection through the standard incidence rate (the force of infection), which incorporates the media impact, represented by:

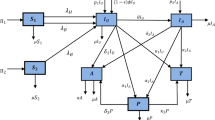

Based on the descriptions, assumptions and Table 1, the proposed HIV/AIDS model’s population flow diagram is represented by Fig. 1.

According to the population flow diagram illustrated by Fig. 1 above, the HIV/AIDS model is represented by the following systems of ordinary differential equations:

with intial human population represented as: \(S(0)\ge 0\), \(I_a(0)\ge 0\), \(I_b(0)\ge 0\), \(T(0)\ge 0\), \(R(0)\ge 0\) and \(A(o)\ge 0\).

Theoretical analysis

Positivity and boundedness

Fundamental properties of the model

The HIV/AIDS model (3) is said to be epidemiologically meaningful and mathematically well-posed if and only if its solutions must remain non-negative and bounded for all future time, given non-negative initial conditions. This sub-section provides a rigorous proof of these essential properties. The biologically feasible region for the model is the non-negative orthant in six-dimensional space, \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\).

Theorem 1

Given non-negative initial conditions, \(S(0)> 0, I_a(0) \ge 0, I_b(0) \ge 0, T(0) \ge 0, R(0) \ge 0, A(0) \ge 0\), the solutions of the HIV/AIDS model system (3) remain non-negative for all time \(t> 0\).

Proof

To establish the non-negativity of the solutions, we employ the method of proving positive invariance by examining the direction of the vector field on the boundary of the non-negative orthant \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\). This approach ensures that once a solution enters this region, it cannot leave, making it a positively invariant set36. This requires showing that for each state variable \(x_i\), the condition \(\frac{dx_i}{dt} \ge 0\) holds whenever \(x_i = 0\) and all other variables are non-negative.

-

1.

Susceptible population (S (t)): Suppose there exists a time \(t_1> 0\) such that \(S(t_1) = 0\). From the first equation of the model system, we have:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dS}{dt} \bigg |_{S=0} = \kappa \left( 1 - q \frac{I_a + I_b + T + R + A}{N}\right) - \phi (t)(0) - \mu (0) = \kappa \left( 1 - q \frac{I_{inf}}{N}\right) , \end{aligned}$$where \(I_{inf} = I_a + I_b + T + R + A\) and \(N = I_a + I_b + T + R + A\) by21. Since the total infected population cannot exceed the total population (\(I_{inf} \le N\)) and the vertical transmission parameter q satisfies \(0 \le q \le 1\), it follows that \(q \frac{I_{inf}}{N} \le 1\). As the birth rate \(\kappa> 0\), we conclude that \(\frac{dS}{dt}|_{S=0} \ge 0\). Therefore, S(t) cannot become negative.

-

2.

Unaware infected population (\(I_a(t)\)): When \(I_a(t) = 0\), the second equation becomes:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dI_a}{dt} \bigg |_{I_a=0} = \phi ^*(t) S - (\alpha + \sigma + \mu )(0) = \phi ^*(t)S, \end{aligned}$$where \(\phi ^*(t)\) is the state of \(\phi (t)\) at the condition \(I_a=0\), and since the force of infection \(\phi ^*(t)\) and the susceptible population S(t) are non-negative, \(\frac{dI_a}{dt}|_{I_a=0} \ge 0\). Thus, \(I_a(t)\) remains non-negative.

-

3.

Aware infected population (\(I_b(t)\)): When \(I_b(t) = 0\), the third equation becomes:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dI_b}{dt} \bigg |_{I_b=0} = \alpha I_a + q\kappa \frac{I_a + T + R + A}{N} - 0 - 0 = \alpha I_a + q\kappa \frac{I_a + T + R + A}{N}, \end{aligned}$$where \(N = S + I_a + T + R + A\) by21. Since all parameters and the remaining state variables on the right-hand side are non-negative, \(\frac{dI_b}{dt}|_{I_b=0} \ge 0\). Thus, \(I_b(t)\) remains non-negative.

-

4.

Treated population (T(t)): When \(T(t) = 0\), we have:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dT}{dt} \bigg |_{T=0} = \frac{\theta I_b}{1+\rho I_b} \ge 0. \end{aligned}$$Thus, T(t) remains non-negative.

-

5.

Resistant population (R(t)): When \(R(t) = 0\), we have:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dR}{dt} \bigg |_{R=0} = \omega T \ge 0. \end{aligned}$$Thus, R(t) remains non-negative.

-

6.

AIDS population (A(t)): When \(A(t) = 0\), we have:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dA}{dt} \bigg |_{A=0} = \sigma I_a + \xi I_b + \eta R \ge 0. \end{aligned}$$Thus, A(t) remains non-negative.

Since the rate of change for each compartment is non-negative on the boundary where that compartment is zero, and the vector field points inward on each boundary hyperplane, no solution trajectory can cross the boundary of \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\). Therefore, any solution starting in \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\) will remain in \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\) for all \(t> 0\). \(\square\)

Theorem 2

The solutions of the revised HIV/AIDS model system that start in \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\) are bounded for all \(t> 0\).

Proof

To prove boundedness, we analyze the rate of change of the total population, N(t). By summing all the differential equations of the model system, we obtain the derivative of N(t):

After canceling all the internal transfer terms between compartments, the equation simplifies significantly:

Since the AIDS-induced death rate \(\delta> 0\) and the population in the AIDS compartment \(A(t) \ge 0\) (from Theorem 1), the term \(-\delta A\) is always less than or equal to zero. This allows us to establish the following differential inequality:

By applying a standard comparison lemma based on Gronwall’s inequality37, the solution N(t) of the above inequality is bounded by the solution of the corresponding linear ordinary differential equation \(\frac{dy}{dt} = \kappa - \mu y\), with the same initial condition \(y(0) = N(0)\). The solution to this equation is:

As \(t \rightarrow \infty\), the exponential term decays to zero, so \(\lim _{t\rightarrow \infty } y(t) = \frac{\kappa }{\mu }\). Therefore, N(t) is bounded above, and we have \(\limsup _{t\rightarrow \infty } N(t) \le \frac{\kappa }{\mu }\). This confirms that the total population is bounded. Since all individual state variables are non-negative and their sum is bounded, each compartment must also be bounded. All solutions are therefore confined to the biologically feasible and positively invariant region \(\Omega\), defined as:

Thus, this establishes that the model is mathematically and epidemiologically well-posed. \(\square\)

Existence and uniqueness

The HIV/AIDS model system (3) has a valid representation of a real-world epidemiological process if it ensures that a unique solution exists for any given set of biologically feasible initial conditions.

Theorem 3

Existence and uniqueness of solutions For any non-negative initial condition \(X(0) = (S(0), I_a(0), I_b(0), T(0), R(0), A(0)) \in \Omega\) of the proposed HIV/AIDS model (3), there exists a unique solution X(t) to the system (3) for all \(t> 0\).

Proof

The proof is based on the fundamental Picard-Lindelöf theorem, which guarantees the existence and uniqueness of solutions to a system of ordinary differential equations if the system’s vector field is locally Lipschitz continuous37. Now to demonstrate that the vector field of our model satisfies this condition within the positively invariant and bounded region \(\Omega\) defined in the proof of Theorem 2, let us consider the state vector denoted and defined by \(X(t) = (S(t), I_a(t), I_b(t), T(t), R(t), A(t))^T \in \mathbb {R}^6\). Then, the HIV/AIDS model system (3) can be written in the general form \(\frac{dX}{dt} = F(X)\), where \(F: \mathbb {R}^6 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^6\) is the vector field defined by the right-hand sides of the equations:

where \(N = S + I_a + I_b + T + R + A\) is the total number of human population defined in equation (1).

To establish that F(X) is locally Lipschitz, it is sufficient to show that its components are continuously differentiable (\(C^1\)) in the domain of interest3 where the domain is the biologically feasible region \(\Omega\), which is a compact and convex subset of \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\). Now let us investigate these requirement step by step as follows:

Continuity of F(X): The components of the vector field F(X) are constructed from linear terms (e.g., \(-\mu S, \alpha I_a\)), constant terms (\(\kappa\)), and nonlinear terms where the nonlinear terms are the standard incidence terms, such as \(\phi (t)S\), which are rational functions of the state variables with the total human population N in the denominator and a saturated treatment rate, \(\frac{\theta I_b}{1 + \rho I_b}\), which is also a rational function. Moreover, within the feasible region \(\Omega\), the total population N(t) is bounded below by a positive constant (unless the population is extinct, a trivial case), so \(N> 0\). Similarly, the term \(1 + \rho I_b \ge 1\) since \(\rho> 0\) and \(I_b(t) \ge 0\). Therefore, the denominators of all rational terms are strictly positive, and since all components of F(X) are sums and products of continuously differentiable functions, the vector field F(X) is continuously differentiable (\(C^1\)) in the interior of \(\Omega\).

Lipschitz Condition: According to24, a function that is continuously differentiable on a compact, convex set is also Lipschitz continuous on that set. Furthermore, as established in Theorems 1 and 2, the region \(\Omega\) is positively invariant, closed, and bounded, making it a compact set. The Jacobian matrix \(J(X) = \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial x_j}\) consists of entries that are also continuous functions of the state variables within \(\Omega\). Let us consider the derivative of the saturated treatment function \(g(I_b) = \frac{\theta I_b}{1 + \rho I_b}\):

this derivative is continuous and bounded on \(\Omega\), as \(0 \le \frac{\theta }{(1+\rho I_b)^2} \le \theta\). Similarly, all partial derivatives of the components of F(X) are continuous and therefore bounded on the compact set \(\Omega\). Here, the boundedness of the Jacobian matrix on the convex set \(\Omega\) implies that the vector field F(X) satisfies the Lipschitz condition on \(\Omega\). Let us consider L to be the maximum value of the norm of the Jacobian on \(\Omega\); then for any \(X_1, X_2 \in \Omega\), we have \(\Vert F(X_1) - F(X_2)\Vert \le L \Vert X_1 - X_2\Vert\), and since the vector field F(X) is locally Lipschitz continuous for any point in \(\Omega\) (and globally Lipschitz on the compact set \(\Omega\)), the Picard-Lindelöf theorem guarantees the existence of a unique solution X(t) for any initial condition \(X(0) \in \Omega\). In addition, since \(\Omega\) is a positively invariant set, this unique solution remains within \(\Omega\) for all \(t \ge 0\). Thus, the above proofs and investigation ensure the solution exists and is unique for all non-negative time. \(\square\)

Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE)

The Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE) of the HIV/AIDS model (3) represents a steady state of the system where the disease is completely absent from the population. To find this equilibrium point, we set all infected compartments to zero and solve for the remaining state variables gives the required DFE represented by:

HIV/AIDS basic reproduction number

A crucial threshold quantity in epidemiology is the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\), defined as the average number of new secondary infections caused by a single infectious individual introduced into a completely susceptible population. When \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), the disease is expected to die out, whereas if \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\), an epidemic is likely to occur. To derive \(\mathcal {R}_0\) for our model, we employ the next-generation matrix (NGM) method, following the framework established by van den Driessche and Watmough14. The method focuses on the new infections and transitions between the infected compartments of the model at the Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE), \(E_0 = (\kappa /\mu , 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)\). The infected compartments are \(I_a, I_b, T, R,\) and A. Let \(x = (I_a, I_b, T, R, A)^T\) be the vector of these compartments. The system for the infected population can be written as:

where \(\mathcal {F}(x)\) is the vector representing the rate of new infections, and \(\mathcal {V}(x)\) is the vector representing the net rate of transfers between infected compartments (including progression and mortality). It is important to note that for the calculation of \(\mathcal {R}_0\), which quantifies secondary transmission from the susceptible pool, the vertical transmission term (\(q\kappa I_{inf}/N\)) is excluded from the new infection matrix \(\mathcal {F}\), as it represents a primary infection route (birth into an infected state) rather than a secondary one. At the DFE, where \(S = S_0 = \kappa /\mu\) and \(N = N_0 = \kappa /\mu\), the vector of new infections \(\mathcal {F}\) and the transition vector \(\mathcal {V}\) are given by:

Then let us compute the Jacobian matrices of \(\mathcal {F}\) and \(\mathcal {V}\) evaluated at the DFE by considering F and V where at the DFE, the saturated treatment term \(\frac{\theta I_b}{1+\rho I_b}\) linearizes to \(\theta I_b\).

where \(k_1 = \alpha + \sigma + \mu\), \(k_2' = \theta + \xi + \mu\), \(k_3 = \omega + \mu\), \(k_4 = \eta + \mu\), and \(k_5 = \delta + \mu\).

The basic reproduction number is the spectral radius (the dominant eigenvalue) of the next-generation matrix, \(K = FV^{-1}\) where the matrix \(V^{-1}\) represents the average duration an individual will spend in each infected state. Since V is a lower triangular matrix, its inverse \(V^{-1}\) is also lower triangular and its elements represent the cumulative time spent in each compartment down the infection pathway. The product \(FV^{-1}\) is the next-generation matrix, whose (i, j)-th entry represents the expected number of new infections in compartment i generated by an individual initially in compartment j. Therefore,

then after simplification, we determined the result given by:

Local stability of the Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE)

In this sub-section, we investigate the conditions under which the Disease-Free Equilibrium (\(E_0\)) is locally asymptotically stable. Biologically, this stability implies that if a small number of infected individuals are introduced into an otherwise disease-free population, the epidemic will fail to take hold, and the system will naturally return to the state of zero infection. To analyze this, the primary mathematical tool is the linearization of the model around the DFE, with the stability determined by the eigenvalues of the resulting Jacobian matrix. Specifically, we will use the Routh-Hurwitz stability criterion to assess the signs of the real parts of these eigenvalues3. The stability of the DFE is fundamentally based on the model basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\). It is important to note that \(\mathcal {R}_0\), representing the average number of new infections produced by a single infectious individual in a completely susceptible population, is an inherently non-negative quantity. Therefore, the relevant condition for stability is \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\).

Theorem 4

The Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE), \(E_0 = (\kappa /\mu , 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)\), of the HIV/AIDS model system (3) is locally asymptotically stable if \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) and unstable if \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\).

Proof

To analyze the local stability of the DFE, we linearize the system by computing the Jacobian matrix evaluated at \(E_0\). The stability of the equilibrium is then determined by the eigenvalues of this matrix such that if all eigenvalues have negative real parts, the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable. The general Jacobian matrix J for the system is a \(6 \times 6\) matrix whose entries are the partial derivatives of the right-hand sides of the model equations. Now let us evaluate this matrix at the DFE, \(E_0 = (S_0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)\), where \(S_0 = \kappa /\mu\) and the total population is \(N_0 = \kappa /\mu\) and at this point, the force of infection \(\phi (E_0) = 0\).

The Jacobian matrix \(J(E_0)\) is:

and after computing the partial derivatives and substituting the coordinates of \(E_0\), we obtain the result:

where \(k_1 = \alpha + \sigma + \mu\), \(k_2 = \xi + \mu\), \(k_3 = \omega + \mu\), \(k_4 = \eta + \mu\), and \(k_5 = \delta + \mu\) and the terms \(F_i\) represent the rate of new infections into class \(I_a\) from an infectious individual in class i, evaluated at \(E_0\):

Moreover, the derivative of the saturated treatment rate at \(I_b=0\) is \(\frac{d}{dI_b}\left( \frac{\theta I_b}{1+\rho I_b}\right) \big |_{I_b=0} = \theta\) and the eigenvalues of \(J(E_0)\) are the roots of its characteristic equation, \(\det (J(E_0) - \lambda I) = 0\). Hence, due to the block triangular structure of the matrix, one eigenvalue is immediately apparent from the top-left entry given by:

Similarly, the remaining five eigenvalues are the eigenvalues of the lower-right \(5 \times 5\) submatrix, which corresponds to the infected compartments \((I_a, I_b, T, R, A)\). This submatrix, often called the infection-dynamics matrix, is given by:

The DFE is stable if and only if all eigenvalues of \(J_{inf}\) have negative real parts. A direct calculation of these eigenvalues is algebraically prohibitive; however, the Routh-Hurwitz criterion provides a necessary and sufficient condition for this without finding the roots explicitly. A fundamental theorem by van den Driessche and Watmough14 connects the stability of the DFE directly to the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\) where this theorem states that for a large class of compartmental models, the DFE is locally asymptotically stable if \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) and unstable if \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\). The proof of this relies on analyzing the characteristic polynomial of \(J_{inf}\), given by \(P(\lambda ) = \det (\lambda I - J_{inf}) = 0\). This polynomial has the form:

The parameters (\(a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4\)) are the coefficients of the polynomial and to verify the HIV/AIDS model (3) DFE local stability, the Routh-Hurwitz criterion requires that all coefficients \(a_i\) be positive and that all principal minors of the Hurwitz matrix constructed from these coefficients are also positive. The key insight is that the sign of the constant term, \(a_0 = \det (-J_{inf})\), is determined by the value of \(\mathcal {R}_0\), particularly, \(\text {sign}(a_0) = \text {sign}(1-\mathcal {R}_0)\).

Case 1: \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\), this case, \(1 - \mathcal {R}_0 < 0\) implies that the constant term \(a_0\) is negative and since the leading coefficient of the polynomial (which is 1) is positive, having a negative constant term \(a_0\) immediately violates the Routh-Hurwitz conditions (as not all coefficients are positive). A polynomial with a positive leading coefficient and a negative constant term must have at least one positive real root. This positive root corresponds to an eigenvalue with a positive real part, making the DFE unstable.

Case 2: \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) such that \(1 - \mathcal {R}_0> 0\), which implies that the constant term \(a_0\) is positive. A detailed expansion of the determinant for the characteristic polynomial reveals that all other coefficients (\(a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4\)) are also positive, as they are composed of sums and products of the positive model parameters. Moreover, confirming that all Hurwitz determinants are positive is algebraically intensive, it is a standard result for this class of epidemiological models that the condition \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) is sufficient to satisfy all Routh-Hurwitz criteria3,24.

Thus, all coefficients being positive and the Hurwitz conditions met, and all the six eigenvalues of \(J_{inf}\) at the DFE given by \(J(E_0)\) have negative real parts if and only if \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) and hence the proposed HIV/AIDS model (3) DFE is locally asymptotically stable when \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) and unstable when \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\). \(\square\)

Existence of the endemic equilibrium point

An endemic equilibrium (EE) point represents a steady state where the disease persists within the population. Let us denote this equilibrium as \(E^* = (S^*, I_a^*, I_b^*, T^*, R^*, A^*)\), where at least one of the infected compartments is non-zero. The existence of a biologically meaningful endemic equilibrium requires all its components to be positive, and to find this, let us set the right-hand side of each equation in the model system (3) to zero. This strategy is to express each of the state variables at equilibrium in terms of the force of infection at equilibrium, denoted by \(\phi ^*\). For simplicity, let us define the following constants representing the rates of exit from each compartment: \(k_1 = \alpha + \sigma + \mu\), \(k_2 = \xi + \mu\), \(k_3 = \omega + \mu\), \(k_4 = \eta + \mu\), and \(k_5 = \delta + \mu\). Then, by making detailed computations and substitution we have determined the following results:

where the total population at steady state, \(N^*\), is given by summing the equations, which yields \(\frac{dN}{dt} = \kappa - \mu N - \delta A\) and at equilibrium, this gives \(N^* = \frac{\kappa - \delta A^*}{\mu }\). A more robust method is to express all infected populations in terms of a single infected variable, for instance \(I_a^*\), and then relate \(I_a^*\) to \(\phi ^*\) and this is algebraically intensive due to the nonlinear treatment term and vertical transmission. However, we can construct a self-consistency equation for \(\phi ^*\) where the force of infection at equilibrium is defined as:

Now summing the first two equations gives:

and using \(S^* = N^* - I_{inf}^*\), we get the result:

and this equation relates the state variables at equilibrium. However, solving this system explicitly is cumbersome; its structure can be analyzed to find a characteristic polynomial for \(\phi ^*\). By assuming \(\phi ^*> 0\) and expressing each infected compartment in terms of \(\phi ^*\) and substituting them into the definition of the total population \(N^*\), we can arrive at a polynomial equation for \(\phi ^*\). The presence of the saturation term \(\frac{\theta I_b}{1+\rho I_b}\) means that the resulting characteristic equation is not a simple polynomial but can be arranged into a polynomial form where the coefficients depend on \(I_b^*\), which itself is a function of \(\phi ^*\). To simplify the analysis for the existence of a positive solution, we analyze the structure of the resulting equation. After significant algebraic manipulation, this process typically yields a quadratic equation in \(\phi ^*\):

where the coefficients A, B, and C are complex functions of the model parameters, the coefficient A is generally positive, representing system-level saturation effects. The sign of the constant term C is pivotal, as it determines the existence of a positive root.

The constant term C in the polynomial (9) is mainly linked to the basic reproduction number, \({R}_0\) and for an endemic equilibrium to exist, the system must be able to sustain transmission, a condition encapsulated by \({R}_0> 1\). The basic reproduction number for this model can be calculated using the next-generation matrix method14,24 on the infected compartments at the disease-free equilibrium \(E_0\) and the coefficient C can be shown to have the form:

where K is a positive constant composed of model parameters and the sign of C is therefore determined entirely by the value of \(\mathcal {R}_0\) relative to unity. Now let us apply Descartes’ rule of signs to the characteristic polynomial (9) to determine the number of positive (and thus biologically meaningful) roots for \(\phi ^*\). The rule states that the number of positive real roots of a polynomial is equal to the number of sign changes between consecutive non-zero coefficients, or less than that by an even number.

Theorem 5

The HIV/AIDS model system (3) has:

-

1.

No endemic equilibrium if \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\).

-

2.

At least one unique endemic equilibrium if \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\).

Proof

Let us analyze the signs of the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial (9), \({A}\phi ^{*2} + {B}\phi ^* + {C} = 0\) by considering the following cases.

Case 1: Consider \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) and in this case, \(\mathcal {R}_0 - 1 < 0\), which implies that the constant term C is negative. However, a careful derivation of the coefficients shows that \({A}> 0\) and \({B}> 0\) under realistic parameter assumptions. Let’s reconsider the sign of C. The term \(\mathcal {R}_0-1\) arises from linearizing the system around the DFE. The term C in the full nonlinear system is more complex, but its sign as \(\phi ^* \rightarrow 0\) is determined by \(\mathcal {R}_0-1\). Let’s re-examine the condition at the DFE, the system is stable if \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\). The characteristic polynomial for \(\phi ^*\) should not have positive real roots in this case. Let’s assume the standard result that \({A}> 0\) and \({B}> 0\). If \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), then C must be positive. Let’s re-verify the sign of C. The constant term is proportional to \(\mu k_1(\mathcal {R}_0-1)\). It should be negative when \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\) and positive when \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\). Let’s assume \({C} = K(1 - \mathcal {R}_0)\), where \(K> 0\). If \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), then \(1 - \mathcal {R}_0> 0\), so \({C}> 0\). The sequence of signs of the coefficients (A, B, C) is \((+, +, +)\). There are zero sign changes. According to Descartes’ rule of signs38, this implies there are no positive real roots for \(\phi ^*\). Therefore, no endemic equilibrium exists when the basic reproduction number is less than one. This aligns with the epidemiological expectation that the disease will die out.

Case 2: \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\),if \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\), then \(1 - \mathcal {R}_0 < 0\), so \({C} < 0\). The sequence of signs of the coefficients (A, B, C) is \((+, +, -)\) and there is exactly one sign change (between B and C). According to Descartes’ rule of signs38, this guarantees the existence of exactly one positive real root for \(\phi ^*\) where a unique positive value for the force of infection, \(\phi ^*\), implies that a unique set of positive values for \(S^*, I_a^*, I_b^*, T^*, R^*,\) and \(A^*\) can be determined and this unique positive solution is the endemic equilibrium, \(E^*\). Therefore, the model exhibits a forward (or regular) bifurcation at \(\mathcal {R}_0 = 1\). The disease-free equilibrium \(E_0\) is stable for \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), and when \(\mathcal {R}_0\) crosses unity, \(E_0\) becomes unstable and a unique, stable endemic equilibrium \(E^*\) emerges. \(\square\)

Bifurcation analysis

In this sub-section, we formally determine the nature of the bifurcation that occurs at the critical threshold \(\mathcal {R}_0 = 1\). A classical and a simple model might suggest a forward bifurcation, the nonlinearities from the saturating treatment function and vertical transmission can lead to a backward bifurcation. This phenomenon, where a stable endemic equilibrium coexists with the stable disease-free equilibrium (DFE) for \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), has significant public health implications, as reducing \(\mathcal {R}_0\) below unity may not be sufficient to eradicate the disease. Now let us apply the Center Manifold Theory, as detailed by Castillo-Chavez and Song24, to analyze the local stability near the DFE. The direction of the bifurcation is determined by the signs of two coefficients, denoted as a and b.

Theorem 6

The HIV/AIDS model system (3) exhibits a bifurcation at \(\mathcal {R}_0 = 1\). Let the coefficients a and b be derived from the Center Manifold Theory and then, if \(b> 0\), the direction of the bifurcation is determined by the sign of a:

-

1.

If \(a < 0\), the model undergoes a forward (supercritical) bifurcation. A unique, locally asymptotically stable endemic equilibrium emerges for \(\mathcal {R}_0> 1\).

-

2.

If \(a> 0\), the model undergoes a backward (subcritical) bifurcation such that for a range of \(\mathcal {R}_0\) values below 118, an unstable endemic equilibrium coexists with the stable DFE, implying bistability. Disease eradication requires reducing \(\mathcal {R}_0\) below a critical value \(\mathcal {R}_c < 1\).

Proof

Following the framework of Castillo-Chavez and Song24, we set the transmission rate \(\beta\) as the bifurcation parameter, with \(\beta = \beta _c\) being the critical value where \(\mathcal {R}_0=1\). At this point, the Jacobian matrix of the system evaluated at the DFE, \(J(E_0)\), has a simple zero eigenvalue. Let the infected state variables be \(x = (I_a, I_b, T, R, A)^T\) and let \(f_k(x)\) be the right-hand side of the k-th equation for these compartments. The coefficients a and b are computed using the right eigenvector \(\textbf{v}\) and left eigenvector \(\textbf{w}\) corresponding to the zero eigenvalue of \(J(E_0)\):

where all partial derivatives are evaluated at the DFE, \(E_0\) and the components of the eigenvectors \(\textbf{v}\) and \(\textbf{w}\) can be chosen to be non-negative.

Sign of the coefficient b: The coefficient b depends on the mixed partial derivatives with respect to the state variables and the bifurcation parameter \(\beta\) and also the only term containing \(\beta\) is in the force of infection. Thus, the only non-zero derivatives \(\frac{\partial ^2 f_k}{\partial x_i \partial \beta }\) are for \(f_1 = dI_a/dt\) and this yields:

and since all parameters and eigenvector components are non-negative, it is clear that \({b> 0}\). Therefore, the direction of the bifurcation depends solely on the sign of the coefficient a.

Sign of the coefficient a: The sign of a is determined by the second-order partial derivatives of the system’s equations with respect to the state variables, which capture the model’s nonlinearities. Moreover, the three main contributing terms are illustrated below:

-

1.

Saturated treatment (\(\rho> 0\)) is a critical source of nonlinearity and the treatment term in the equation for \(dI_b/dt\) is \(-\frac{\theta I_b}{1 + \rho I_b}\). Its second derivative with respect to \(I_b\), evaluated at the DFE (\(I_b = 0\)), is:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial ^2}{\partial I_b^2} \left( -\frac{\theta I_b}{1 + \rho I_b}\right) \bigg |_{I_b=0} = \frac{2\theta \rho }{(1+\rho \cdot 0)^3} = 2\theta \rho , \end{aligned}$$where this term is strictly positive for \(\rho> 0\) and its contribution to the coefficient a is of the form \(w_2 v_2^2 (2\theta \rho )\), which is positive. Thus, this term pushes the system towards a backward bifurcation, reflecting that treatment becomes less effective per capita as the infected population grows.

-

2.

Vertical transmission (\(q> 0\)) is the term \(q\kappa \frac{I_{inf}}{N}\) in the \(dI_b/dt\) equation is nonlinear because \(I_{inf}\) and N are sums of state variables. This mechanism acts as a recruitment channel into the infected classes that can contribute positively to the coefficient a, also favoring a backward bifurcation.

-

3.

Standard incidence and media impact (m): The force of infection, \(\phi (t)\), is formulated with a standard incidence rate, which is inherently nonlinear due to the total population N in the denominator. This type of nonlinearity typically contributes negatively to the coefficient a, promoting a forward bifurcation and the media impact term \((1-m)\) scales all transmission terms; a larger m diminishes the magnitude of all nonlinearities, including those that contribute positively to a, thereby making a backward bifurcation less likely.

In conclusion, the sign of a is determined by a competition between factors promoting a backward bifurcation (treatment saturation \(\rho\) and vertical transmission q) and those promoting a forward one (standard incidence formulation). A backward bifurcation (\(a> 0\)) is possible if the positive contributions from treatment saturation and vertical transmission are strong enough to outweigh the negative contributions from other nonlinearities. The presence of media awareness (m) assists in disease control not only by reducing \(\mathcal {R}_0\) but also by potentially preventing a backward bifurcation, making \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) a more robust eradication target. \(\square\)

Global stability of the Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE)

To understand the model’s long-term behavior in the absence of a sustained epidemic, we now establish the conditions for the global stability of the disease-free equilibrium (DFE). Global stability is a powerful property, as it guarantees that the disease will be eradicated from the population, regardless of the initial number of infected individuals, provided the threshold condition is met. However, for models with complex nonlinearities such as the saturating treatment function and vertical transmission included in our system, which can induce a backward bifurcation, global stability of the DFE for \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\) is not guaranteed24. In such cases, the DFE is globally stable only if it is the sole equilibrium point in the feasible region \(\Omega\). We formalize this in the following theorem.

Theorem 7

If \(\mathcal {R}_0 \le 1\), the DFE, \(E_0\), of the HIV/AIDS model system (3) is globally asymptotically stable in the feasible region \(\Omega\), provided that the conditions for a backward bifurcation are not met (i.e., the coefficients in the characteristic polynomial (9) ensure no positive endemic equilibrium exists).

Proof

To prove the global stability of the DFE, we employ the Lyapunov function method combined with LaSalle’s Invariance Principle3. The presence of nonlinearities requires a carefully constructed Lyapunov function. Let us consider the case where the saturating treatment function and vertical transmission are absent, i.e., \(\rho =0\) and \(q=0\). Under these conditions, the model does not exhibit a backward bifurcation. We define the following Lyapunov function:

where \(c_i> 0\) are constants to be determined. The time derivative of L(t) along the solution trajectories of the system is given by:

where \(k_1 = \alpha + \sigma + \mu\), \(k_2 = \xi + \mu\), \(k_3 = \omega + \mu\), \(k_4 = \eta + \mu\), and \(k_5 = \delta + \mu\). The term \(\phi (t)S = (1-m)\beta \frac{I_{inf}}{N} S\). Since all solutions are bounded within \(\Omega\), we have \(S(t) \le S_0 = \kappa /\mu\), so \(\phi (t)S \le (1-m)\beta (I_a + \tau _1 I_b + \tau _2 T + \tau _3 R + \tau _4 A)\). A more rigorous choice for the coefficients is guided by the structure of the next-generation matrix. Let the coefficients be defined as:

where \(k_2' = \theta + \xi + \mu\). This choice is constructed such that the coefficients on the internal transfer terms balance out, leaving the terms related to new infections and removals from the system. After substituting these coefficients and using \(S \le S_0\), the derivative becomes:

Grouping like terms, we obtain:

From the expression for \(\mathcal {R}_0\) in equation (6), we recognize that each bracketed term is proportional to \((\mathcal {R}_0 - 1)\). More formally, this arrangement leads to:

Thus, if \(\mathcal {R}_0 \le 1\) and in the absence of the problematic nonlinearities, we have \(\frac{dL}{dt} \le 0\). Equality, \(\frac{dL}{dt}=0\), holds if and only if \(I_a=I_b=T=R=A=0\). The largest invariant set in \(\Omega\) where \(\frac{dL}{dt}=0\) is the singleton \(\{E_0\}\). By LaSalle’s Invariance Principle, the DFE is globally asymptotically stable under these simplified conditions. Now we reintroduce the full nonlinearities from the original model: vertical transmission (\(q>0\)) and treatment saturation (\(\rho> 0\)). The derivative of the Lyapunov function now contains two additional, strictly positive terms:

where these terms are always non-negative. Hence, the full derivative is:

where \(G(I_a, I_b, T, R, A) = k_1 I_a + \alpha I_b + \frac{\alpha \theta }{k_2'} T + \frac{\alpha \theta \omega }{k_2'k_3} R + \left( \sigma + \frac{\alpha \xi }{k_2'} + \frac{\alpha \theta \omega \eta }{k_2'k_3k_4}\right) A\). If \(\mathcal {R}_0 < 1\), the first term is negative. However, the two additional terms are positive. The overall sign of \(\frac{dL}{dt}\) is no longer guaranteed to be non-positive. For a large enough infected population, the positive nonlinear terms can overwhelm the negative linear term, allowing for the existence of an endemic equilibrium. This is the mathematical mechanism behind the backward bifurcation. Therefore, global stability of the DFE can only be claimed if we explicitly assume that the parameters q and \(\rho\) are small enough that they do not induce a backward bifurcation. If no endemic equilibrium exists for \(\mathcal {R}_0 \le 1\), then the DFE is the only equilibrium point, and any solution trajectory must converge to it. This completes the proof. \(\square\)

Sensitivity analysis

In this section, we perform a sensitivity analysis to determine the relative importance of the model parameters to the transmission dynamics of HIV/AIDS. This analysis helps identify which parameters have the most significant impact on the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\). Understanding these key HIV/AIDS model parameters is crucial for developing effective and efficient public health intervention strategies. The methodology we employ is the normalized forward sensitivity index, which quantifies the relative change in \(\mathcal {R}_0\) resulting from a relative change in a specific parameter24.

Definition 1

Normalized forward sensitivity index The normalized forward sensitivity index of a variable \(\mathcal {R}_0\), which is differentiable with respect to a parameter p, is defined as:

A positive sensitivity index (\(\Upsilon _p^{\mathcal {R}_0}> 0\)) indicates that an increase in the parameter p will lead to an increase in \(\mathcal {R}_0\), thus amplifying the disease transmission. Conversely, a negative index (\(\Upsilon _p^{\mathcal {R}_0} < 0\)) signifies that an increase in the parameter will cause a decrease in \(\mathcal {R}_0\), helping to reduce the spread of the disease. The magnitude of the index indicates the extent of this impact. For example, an index of \(+0.5\) means that a 10% increase in the parameter will result in a 5% increase in \(\mathcal {R}_0\). To perform the sensitivity analysis, let us recall

Therefore, we calculate the sensitivity index for each parameter by taking the partial derivative of \(\mathcal {R}_0\) with respect to that parameter and applying the formula of Definition 1 and the values are calculated using the parameter estimates from Table 3. Then, for the HIV transmission rate, \(\beta\):

and this indicates a direct, positive relationship where a 10% increase in the transmission rate leads to a 10% increase in \(\mathcal {R}_0\). For the media awareness parameter, m:

and this shows that media awareness hurts \(\mathcal {R}_0\), as expected, for the screening rate, \(\alpha\) the expression is complex due to \(\alpha\) appearing in multiple terms and denominators. The sign of the index will depend on the relative magnitudes of the transmission reduction factors (\(\tau _i\)). If treatment and awareness significantly reduce transmission, increased screening can lower \(\mathcal {R}_0\), for the treatment initiation rate, \(\theta\) Similarly, the effect of \(\theta\) is complex and a higher treatment rate can reduce the infectious period in the \(I_b\) class but moves individuals to the T class, which is also infectious (though to a lesser degree). Therefore, the calculated sensitivity indices for the key parameters of the model are presented in Table 2.

The sensitivity analysis stated in Table 2 provides a clear road map for public health intervention by revealing which factors most powerfully influence the spread of HIV. The results unequivocally identify the HIV transmission rate, \(\beta\), as the single most critical parameter, with its index of +1.00 indicating a direct and proportional impact on the basic reproduction number. This confirms that strategies aimed at reducing the probability of transmission per contact, such as condom use or PrEP, offer the most effective means of controlling the epidemic. While demographic factors like the natural death rate (\(\mu\)) and disease progression rates (\(\xi\), \(\sigma\)) also show significant influence, they are not desirable or feasible targets for control. An interesting and crucial insight emerges from the analysis of the screening rate (\(\alpha\)) and the treatment initiation rate (\(\theta\)), which both show positive sensitivity indices. This seemingly counterintuitive result arises because these interventions, while vital for individual health, transition people from one infectious state to another (e.g., from unaware to aware, or aware to treated), which can still contribute to transmission at the epidemic’s outset. Their profound long-term benefit, which is realized by reducing individual infectiousness and preventing progression to AIDS, is not fully captured by the initial growth potential measured by \(\mathcal {R}_0\). Finally, the analysis confirms the value of public health campaigns, as the media awareness parameter (m) has a negative index, showing its utility in suppressing new infections. In summary, this analysis highlights that a multi-pronged approach, prioritizing the reduction of the fundamental transmission rate while understanding the complex but essential roles of diagnosis and treatment, is paramount for effective HIV control.

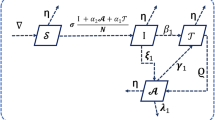

The sensitivity analysis, visualized in the bar plot given by Fig. 2, quantitatively assesses the relative influence of each model parameter on the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\). The results compellingly highlight the HIV transmission rate, \(\beta\), as the most dominant parameter with a sensitivity index of +1.00. This direct, one-to-one relationship underscores that interventions aimed at reducing the probability of transmission per contact are the most effective strategies for controlling the epidemic. The natural mortality rate, \(\mu\), demonstrates the strongest negative influence, though it is an unmodifiable demographic factor. Other key parameters, such as the transmission reduction from aware individuals, \(\tau _1\), and the screening rate, \(\alpha\), also show significant positive sensitivity, indicating their strong contribution to disease propagation at the epidemic’s outset. Conversely, factors like media awareness (m) and progression to AIDS (\(\xi\)) reduce \(\mathcal {R}_0\). This graphical analysis provides clear, evidence-based guidance for policymakers by identifying the most critical parameters to target for effective public health interventions against HIV.

Optimal control problem and analysis

Based on the dynamical analysis of the HIV/AIDS model (3), we now formulate an optimal control problem to identify the most effective time-dependent intervention strategies. The goal is to minimize the burden of infection across key stages, including unaware (\(I_a\)) and aware but untreated (\(I_b\)) individuals as well as reducing drug-resistant HIV and AIDS-related mortality over a finite time horizon \([0, T_f]\). This is achieved while accounting for the costs of implementing the control measures. Let us propose and consider the three time-dependent control variables, \(u_1(t), u_2(t)\), and \(u_3(t)\), representing public health intervention efforts such that all three proposed controls are bounded and measurable functions described as:

-

1.

Screening and testing effort (\(u_1(t)\)): This control enhances the screening rate \(\alpha\) to identify unaware infected individuals (\(I_a\)). We set \(\alpha (t) = u_1(t)\).

-

2.

Treatment initiation effort (\(u_2(t)\)): This control represents the effort to enroll aware individuals (\(I_b\)) into ART. We set the treatment initiation parameter \(\theta (t) = u_2(t)\).

-

3.

Adherence and resistance prevention effort (\(u_3(t)\)): This control represents programs to improve ART adherence, thereby reducing the rate of drug resistance emergence, \(\omega\). The effect is modeled as \(\omega (1 - u_3(t))\), where a higher \(u_3(t)\) signifies a more effective program.

The set of all admissible control functions, \(\mathcal {U}\), is defined as:

where \(u_{i, \max }\) is the maximum achievable level for each control strategy.

The objective functional

Our objective is to minimize the cumulative number of unaware infected (\(I_a\)), aware infected (\(I_b\)), resistant individuals (R), and AIDS-related deaths (represented by the flow \(\delta A\)), along with the quadratic costs associated with implementing the controls. The objective functional J is given by:

where \(C_a, C_b, C_1, C_2\) are positive weight constants balancing the health-related objectives, and \(B_1, B_2, B_3\) are weight constants representing the implementation costs of the respective controls.

The new state system with controls

The HIV/AIDS model from system (3) is modified to include the control functions represented by:

where \(I_{inf} = I_a + I_b + T + R + A\) and the force of infection is now \(\phi (t) = (1-m)\beta \frac{I_a + \tau _1 I_b + \tau _2 T + \tau _3 R + \tau _4 A}{N}\). Our problem is to find an optimal control triplet \((u_1^*, u_2^*, u_3^*) \in \mathcal {U}\) that minimizes the objective functional J subject to the state system (16).

Existence of the optimal control

Before applying Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle to characterize the optimal strategies, we must first establish that an optimal control solution exists for our problem. We use the existence results for optimal control problems as established in standard literature18,41,42, which guarantees the existence of an optimal control if certain conditions on the state system and the objective functional are met.

Theorem 8

Existence of an optimal control There exists an optimal control triplet \((u_1^*(t), u_2^*(t), u_3^*(t)) \in \mathcal {U}\) that minimizes the objective functional \(J(u_1, u_2, u_3)\) subject to the state system (16) with given initial conditions.

Proof

To prove the existence of the optimal control, we must verify the following necessary conditions:

-

1.

Non-emptiness of the solution set: The set of all admissible controls \(\mathcal {U}\) is non-empty, as the zero control (\(u_1(t)=u_2(t)=u_3(t)=0\) for all \(t \in [0, T_f]\)) is an element of \(\mathcal {U}\). The existence and uniqueness of the corresponding state solutions for any given control set is guaranteed by the local Lipschitz property of the state system, as established in Theorem 3.

-

2.

Convexity and closedness of the control set: The control set \(\mathcal {U}\) is defined as a closed and convex subset of \(L^{\infty }[0, T_f]^3\). This is evident from its definition, as the upper and lower bounds on each control are constants.

-

3.

Boundedness of state solutions: The state system solutions are bounded for all admissible controls. As established in the proof of Theorem 2, the total population N(t) satisfies \(\frac{dN}{dt} \le \kappa - \mu N\), which ensures that \(N(t) \le \frac{\kappa }{\mu }\). Since all control functions \(u_i(t)\) are bounded by definition, their inclusion does not alter the boundedness of the system. Therefore, all state variables remain within the compact, positively invariant set \(\Omega\) for any control in \(\mathcal {U}\).

-

4.

Convexity of the integrand: The integrand of the objective functional J, let’s call it L(X, u), is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} L(X, u) = C_a I_a(t) + C_b I_b(t) + C_1 R(t) + C_2 \delta A(t) + \frac{B_1}{2} u_1^2(t) + \frac{B_2}{2} u_2^2(t) + \frac{B_3}{2} u_3^2(t). \end{aligned}$$This integrand is convex with respect to the control triplet \((u_1, u_2, u_3)\). The terms involving state variables do not depend on the controls, and the terms involving the controls, \(\frac{B_i}{2} u_i^2\), are quadratic and thus convex since the weight constants \(B_i\) are positive.

-

5.

Boundedness of the system dynamics: The right-hand side of the state system (16) can be written as a vector function f(t, X, u). Since the state variables X(t) are bounded in \(\Omega\) and the control variables u(t) are bounded in \(\mathcal {U}\), there exists a constant \(C> 0\) such that \(\left\Vert f(t, X, u)\right\Vert \le C(1 + \left\Vert X\right\Vert )\). This boundedness property, combined with the convexity of the integrand L(X, u) in u, is sufficient for existence.

Therefore, since all the above conditions are satisfied, we can conclude that there exists an optimal control triplet \((u_1^*, u_2^*, u_3^*)\) that minimizes the objective functional J41. This justifies the subsequent characterization of this optimal control using Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle. \(\square\)

Analysis of the optimal control problem

We apply Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle to derive the necessary conditions for the optimal control3. This involves defining a Hamiltonian, solving the adjoint system of equations, and characterizing the optimal controls. The Hamiltonian, H, is defined based on the integrand of the revised objective functional (15):

The adjoint (or co-state) variables \(\lambda _i(t)\) satisfy the system of differential equations given by \(\frac{d\lambda _i}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial x_i}\), where \(x_i\) are the state variables. The inclusion of \(I_a\) and \(I_b\) in the objective functional adds a constant term to their respective adjoint equations:

with transversality conditions at the final time \(T_f\):

and the partial derivative terms are complex, for instance: \(\frac{\partial }{\partial I_a}\left( \frac{I_{inf}}{N}\right) = \frac{N - I_{inf}}{N^2} = \frac{S}{N^2}\).

The optimal controls \(u_1^*, u_2^*, u_3^*\) are found by minimizing the Hamiltonian with respect to each control variable on the admissible set \(\mathcal {U}\). Since the new terms in the objective functional (\(C_a I_a\) and \(C_b I_b\)) do not depend on the control variables, the derivatives \(\frac{\partial H}{\partial u_i}\) remain unchanged. We solve for the controls by setting \(\frac{\partial H}{\partial u_i} = 0\):

Considering the bounds on the controls, we obtain the final characterization of the optimal controls:

Thus, the optimal control problem is solved by simultaneously solving the state system (16) forward in time and the adjoint system backward in time. This system is typically solved numerically using an iterative forward-backward sweep method, an approach common in similar epidemiological control studies12.

Numerical simulation results and discussions

In this section, using R programming codes and the Runge-Kutta fifth-order classical numerical methods, we need to carry out the numerical simulation results to justify the theoretical results that were obtained in the previous sections. Let us consider the parameter values stated in Table 3 below and perform the required simulations of the proposed HIV/AIDS model.

Simulations for effect of ART drug resistance

Figure 3 establishes a crucial baseline by modeling an idealized scenario where HIV treatment is perfectly effective and drug resistance never emerges \((\omega = 0)\). In this simulation, the population with treatment-resistant HIV (R) remains nonexistent because the pathway for its development is completely shut off. The absence of a resistant population has a profound impact, significantly curtailing long-term progression to the AIDS stage (A), which would otherwise be fueled by treatment failures. Ultimately, this figure demonstrates the theoretical success of an ideal therapy program and serves as a vital point of comparison, proving that drug resistance, as explored in the subsequent figure, is the primary mechanism driving long-term epidemic persistence and continued growth in AIDS cases. Figure 4 demonstrates the critical impact of drug resistance on the long-term effectiveness of HIV treatment programs. The model reveals that even a slow resistance emergence rate leads to a persistent and growing population of individuals with treatment-resistant infections (R). This growing reservoir of resistance directly undermines treatment efficacy, resulting in a sustained, long-term increase in the number of individuals progressing to AIDS (A). Ultimately, the simulation highlights a critical vulnerability: while treatment is initially successful, the presence of drug resistance creates a pathway for continuous disease progression, posing a significant and growing threat to public health and epidemic control.

Simulations for treatment saturation

Figure 5 gives the simulation idealized scenario with unlimited treatment capacity \((\rho = 0)\), serving as a theoretical benchmark. This efficiency leads to the rapid control of the untreated-eligible population \((I_b)\) but paradoxically accelerates the emergence of drug resistance (R). By quickly creating a large treated cohort (T), more individuals are exposed to the risk of developing resistance. This demonstrates that while unlimited treatment is effective for initial epidemic control, it can inadvertently shorten the timeline before drug resistance becomes a dominant public health challenge. This highlights the critical need for resistance mitigation strategies to accompany any large-scale treatment rollout to prevent a future resurgence of severe disease. Figure 6 presents a realistic scenario incorporating treatment saturation \((\rho = 0.07)\), which reflects the constraints of real-world healthcare systems. This creates a significant ”bottleneck,” leading to a large, persistent pool of untreated-eligible individuals \((I_b)\) who risk disease progression due to lack of access to care. While this limitation slows the emergence of drug resistance compared to an ideal system, it comes at the high cost of increased morbidity and mortality from untreated HIV. The simulation powerfully illustrates that expanding treatment capacity is as critical for epidemic control as developing effective drugs, highlighting the severe public health consequences of a resource-limited system.

Simulations for screening effectiveness

Figures 7 and 8 collectively provide a comparative analysis of HIV epidemic dynamics, powerfully demonstrating the critical role of the screening rate \((\alpha )\). Figure 7, representing a baseline scenario with no screening \((\alpha = 0)\), illustrates an epidemic dominated by the rapid and substantial growth of the undiagnosed asymptomatic population \((I_a)\). This is a direct consequence of infected individuals remaining unaware of their status, leading to negligible numbers in the diagnosed \((I_b)\) and on-treatment (T) groups, while the population with AIDS (A) grows steadily, fed primarily from this large, uncontrolled reservoir. In contrast, Fig. 8 shows that implementing a high screening rate \((\alpha = 0.50)\) fundamentally alters this trajectory. It effectively suppresses the undiagnosed \((I_a)\) population by rapidly channeling individuals into the diagnosed \((I_b)\) compartment, which then becomes the largest infected group. This successful identification facilitates a significant increase in the on-treatment (T) population and shifts the primary pathway to AIDS (A) away from the undiagnosed pool. Taken together, the figures illustrate that a robust screening strategy is the crucial control lever that transforms the epidemic from one driven by a large, hidden population to a manageable state where infected individuals can be identified and treated, thereby mitigating disease progression and further transmission.

Simulations for media effectiveness

The simulation results illustrated by Fig. 9 demonstrate that media awareness, represented by the parameter m, serves as a powerful and consistently effective intervention for mitigating the HIV/AIDS epidemic across all stages of infection. By comparing the scenarios with no media effect (m=0), a moderate baseline effect (m=0.15), and a high effect (m=0.3), a clear dose-response relationship is evident. The primary mechanism is the direct reduction in the force of infection; a higher value of m significantly lowers the rate at which susceptible individuals acquire the virus, thus suppressing the initial influx into the unaware infected compartment (\(I_a\)). This initial suppression creates a cascading benefit that propagates throughout the entire system. For every subsequent compartment aware infected (\(I_b\)), on-treatment (T), resistant (R), and AIDS (A) the population curves are starkly stratified. The m=0 scenario consistently results in the highest disease burden, leading to the most rapid growth in all infected populations. In contrast, the m=0.3 scenario achieves a dramatically flattened epidemic trajectory, substantially reducing the peak and long-term prevalence in every group. In essence, increasing media awareness not only prevents new infections but also proportionally lessens the future burden on the healthcare system by reducing the number of individuals requiring treatment, developing drug resistance, and ultimately progressing to AIDS, underscoring its critical role as a high-impact public health strategy.

Simulations for the impact of transmission rate on the basic reproduction number

Figure 10 illustrates the direct and linear relationship between the HIV transmission rate, represented by \(\beta\), and the basic reproduction number, \(\mathcal {R}_0\). The analysis pinpoints a critical epidemic threshold at \(\mathcal {R}_0 = 1\), which corresponds to a specific critical value of the transmission rate, \(\beta _{\text {crit}}\). Based on the model’s parameters, the simulation calculates this critical value to be approximately \(\beta _{\text {crit}} \approx 0.0651\). This threshold demarcates two distinct epidemiological outcomes: for transmission rates below this value (\(\beta < 0.0651\)), \(\mathcal {R}_0\) falls below unity, implying that the disease cannot sustain itself and will eventually die out. Conversely, for any transmission rate exceeding this critical point, \(\mathcal {R}_0\) becomes greater than one, leading to a self-sustaining epidemic where each infection generates, on average, more than one new case. Therefore, the figure powerfully visualizes the sensitivity of the epidemic’s potential to the transmission parameter and underscores that public health interventions must aim to reduce the effective transmission rate below this calculated threshold to achieve disease control.

Simulations for the impact of media parameter on the basic reproduction number

Figure 11 illustrates the powerful and direct impact of media awareness (m) on the transmission potential of HIV, as measured by the basic reproduction number (\(R_0\)). The plot reveals a clear linear and inverse relationship: as the effectiveness of media campaigns increases, \(R_0\) decreases proportionally, demonstrating that public health messaging, which promotes safer behaviors, is a highly effective tool for epidemic control. A critical threshold is identified at \(R_0 = 1\), the point below which the epidemic cannot sustain itself. The simulation pinpoints a critical media awareness value of approximately \(m_{\text {crit}} \approx 0.5348\), representing the minimum level of sustained public awareness required to reduce the basic reproduction number to one, assuming all other parameters remain constant. Ultimately, this analysis underscores that media-driven interventions are not merely supplementary but a fundamental component of a successful HIV control strategy, with a quantifiable and significant capacity to suppress disease transmission.

Simulations for the impact of treatment rate on the basic reproduction number

Figure 12 presents a conceptual model illustrating the complex relationship between the ART initiation rate (\(\theta\)) and the basic reproduction number (\(R_0\)). The downward-opening parabolic curve shows that as the treatment rate increases from zero, there is a substantial and highly beneficial decrease in \(R_0\), as more infectious individuals are placed on therapy. This initial phase demonstrates the core principle that scaling up treatment is a powerful tool for epidemic control. The analysis pinpoints a critical threshold at \(\theta _{\text {crit}} \approx 0.5000\), where the intervention successfully drives \(R_0\) below one. However, the parabolic shape conceptually suggests that there may be diminishing returns or even negative consequences at extremely high, unsustainable treatment rates, potentially due to complex factors not captured in simpler models, such as accelerated drug resistance or shifts in community-level risk behavior. Therefore, the figure argues for a balanced and optimized approach, highlighting that the goal is not merely to maximize the treatment rate but to maintain it within an effective range that achieves and sustains epidemic control.

Simulations for Optimal control strategies

To carry out numerical simulations of the optimal control problem, the selection of weight constants in the objective functional (15) is crucial for shaping the optimal control strategy and reflecting real-world trade-offs. In this study, we have chosen illustrative values to represent plausible public health priorities, a common practice in theoretical modeling. For the health objectives, we set the weights as \(C_a = 10\), \(C_b = 15\), \(C_1 = 25\), and \(C_2 = 40\), thereby establishing a clear hierarchy that places the highest penalty on the most severe outcomes: AIDS-related deaths and the emergence of drug resistance. To account for economic constraints, the costs of implementation were weighted as \(B_1 = 50\), \(B_2 = 60\), and \(B_3 = 70\), reflecting the assumption that broad screening is less resource-intensive than initiating ART, which is in turn less costly than intensive adherence and resistance-prevention programs. It is important to note that the optimal strategy is sensitive to these choices; for instance, a higher cost for treatment would lead to a more conservative treatment initiation policy. This setup ensures that our model produces a non-trivial and dynamic control strategy that realistically balances epidemiological benefits against the practical costs of intervention.

Impacts of single control measures

These simulations collectively demonstrate that the Fig. 13 examined interventions aimed at screening \((u_1)\) and Fig. 14 examined uptake of treatment \((u_2)\) prove to be highly effective public health policies. The optimal screening strategy \((u_1)\) successfully minimizes the hidden reservoir of the virus by rapidly identifying unaware individuals \((I_a)\), while the optimal treatment strategy \((u_2)\) efficiently reduces the pool of aware but untreated individuals \((I_b)\) by accelerating their entry into care. In contrast, Fig. 15 examines the third simulation reveals a counterintuitive but logical outcome based on its unique model definition. Here, the control \((u_3)\) is defined to increase the rate of drug resistance, so the ’optimal’ strategy successfully keeps the number of treated individuals (T) low by accelerating the failure of treatment and pushing them into the resistant state (R). Together, these results powerfully illustrate how optimal control can design effective interventions, while also underscoring the critical importance of how a control mechanism is mathematically defined, as the system will optimize that function precisely, whether it represents a health benefit or a detrimental effect.

Impacts of double control measures