Abstract

Secure software engineering (SSE) is inevitably linked to DevSecOps which aims to embed security at every phase of the software development life cycle. The adoption of SSE practices is however poorly understood, especially in various adoption phases. This study aims to address this gap by exploring what motivates individuals to adopt SSE practices, and investigating how this differs between the pre-adoption and the post-adoption phase. A survey of people working in software development (N=463) recruited through the Prolific platform was conducted to investigate the determinants of behavioral intention to practice SSE. The measurement instrument was validated with a confirmatory factor analysis. Covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was used to determine associations between constructs based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), technology acceptance model (TAM), and awareness of security risks to developed software and the newest SSE practices. The results indicate that TPB, TAM and awareness explain adoption of SSE practices well. They also indicate major differences between the pre-adoption and post-adoption phases as none of the meaningful associations overlapped between the phases. In the pre-adoption phase, associations of behavioral intention with subjective norm and both awareness constructs have the meaningful effect sizes. Additionally, a non-significant association with perceived usefulness has a small effect size. In the post-adoption phase, behavioral intention was associated with attitude toward SSE and ease of use. Key implications of this study stem from the detected differences between adoption phases which should be considered both in future studies on this topic, and in practical settings in which SSE and thus DevSecOps is being implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secure software engineering (SSE) is a specialized area in software development that emphasizes integrating security measures into the software development life cycle. It is inevitably linked to DevSecOps which aims to embed security at every phase of the software development life cycle1,2,3,4. It introduces security early in the development process, enabling teams to identify and mitigate security risks sooner. This approach promotes collaboration across development, operations, and security teams as ensuring security becomes a shared responsibility. Continuous security checks may be embedded in every stage, from coding to deployment, helping tackle emerging threats and proactively maintaining compliance with industry standards. SSE is thus essential for mitigating risks and vulnerabilities, and is becoming increasingly important as software plays a critical role in various aspects of life and business as also outlined by international standards5. With the escalation of digital technology reliance, ensuring robust software against security threats – both intentional and unintentional – is vital, highlighting the indispensable role of SSE in modern software development6,7.

The effectiveness of SSE practices significantly depends on individual developers’ willingness and ability to adopt these practices. Understanding the factors associated with individual developers’ adoption of SSE is thus essential for creating a security-conscious culture within software development teams8. This understanding is vital for developing strategies and tools that support SSE, enhancing training programs, and ultimately leads to coding practices that are more secure. Therefore, the exploration of individual motivators and barriers in SSE adoption remains a key area of focus in software engineering research9,10.

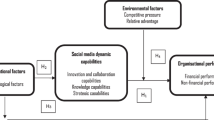

Few studies explored SSE adoption, and each of them did it from a different perspective. One of the first studies on this topic employed the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and its predecessors to study the determinants of behavioral intention to practice SSE11. It indicates only partial support for TPB in this context as only attitude toward behavior and subjective norm were associated with behavioral intention while other factors, such as self-efficacy, were not11. Several later studies leaned on key adoption theories12. First, a study employing the diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory to explain adoption of SSE practices indicated associations between behavioral intent to adopt SSE methods and relative advantage, compatibility, and trialability13. Next, a study leaning on the technology acceptance model (TAM) found that behavioral intention to adopt secure coding methodologies was directly associated with perceived usefulness and only indirectly with ease of use14. Finally, a study proposed to apply the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) for explaining the adoption of SSE practices15 albeit we found no such empirical studies in the literature. Additionally, we found a study building on the technology-organization-environment (TOE) framework that investigated the roles of organizational (e.g., organizational support, organizational justice), technical (e.g., absorption capacity) and individual characteristics (e.g., interest and fun, social needs) in adoption of SSE methods16. To summarize, the presented studies do not combine different theories when studying adoption of SEE practices. They also do not differentiate nor investigate the differences between phases of the adoption process.

In this study, we aim to address the presented gaps in our understanding of SSE adoption. This study makes two key contributions. First, this is one of the first studies to study adoption determinants from competing theories (i.e., TPB and TAM17) therefore contributing to the literature on adoption of SSE practices. Second, it investigates differences between adoption determinants in the pre- and post-adoption phases. This is a step in the opposite direction of the classical adoption theory which aims to unify adoption phases into a single framework18 and therefore contributes to the adoption theory both in the context of SEE practices as well as in general.

Theoretical background

Any technology an enterprise aims to implement into work practice should firstly be adopted by its users. As (secure) software development methods are considered a technology19, several authors investigated factors predicting acceptance of secure software development practices through technology adoption theories. One of the most prevalent theories explaining why some innovations get accepted faster while others remain nearly untouched is explained by Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory (DOI). It explains how a particular innovation idea diffuses over time through a social system20. The principles of DOI theory were readily included in research in the software development research as the basis for understanding the implementation of particular methodology or developing new models (e.g.,21,22,23).

The second set of most significant theories used in research on adoption of software development methods among individuals are the technology acceptance model (TAM)24 and its derivatives (e.g., TAM225)22,26. The original theory is based on three core constructs: 1) perceived usefulness of the technology, 2) perceived ease of its use, and 3) the intention to adopt the technology. Additionally, a target construct is the actual use of the technology. The succeeding TAM2 adds several more factors. The most significant of them (i.e., the one directly influencing the intention) is the subjective norm. Subjective norm refers to a belief of potential user that people who are important to them will approve and support the adoption of particular technology27. Apart from subjective norm, perceived usefulness is predicted by an image, job relevance, output quality, and result demonstrability, while subjective norm is moderated by voluntariness and experience28.

Venkateshs’ unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (namely, UTAUT and UTAUT2)29,30 and Ajzens’ theory of planned behavior (TPB)31 are the final established theories in literature on software development enterprises’ methodology adoption. Both are typical individual-centric theories for predicting technology-related behavior. TPB, which is a widely used theory in variety of topics, such as32,33,34,35, is based on three core constructs: 1) subjective norm, 2) attitude toward behavior, and 3) perceived behavioral control (a degree to which an individual believes performing particular behavior is easy or difficult36). These predict behavioral intention, while the latter finally predicts an actual behavior. UTAUT approaches a similar problem slightly differently - with a more technology-focused approach. Behavioral (adoption) intention is predicted by four factors: 1) expectation of performance, 2) expectation of effort, 3) social influence, and 4) facilitating conditions29. UTAUT2 adds additional factors to the original UTAUT model (i.e., hedonic motivation, price value, and habit)30. While the UTAUT2 adds additional factors as direct predictors of intention, it drops voluntariness from moderating factors. Hence, it only keeps gender, age, and experience30. Both theories were used in the field of software development in previous research (e.g., TPB26,37,38, UTAUT(2)15,39,40, however, some of the factors proposed by UTAUT(2) may not seem entirely suitable for predicting adoption of SSE practices.

When it comes to understanding the factors driving the process of adoption of SSE practices, the process depends not only on technical aspects but also on fostering a culture of open communication, shared responsibility, respect, and trust (as in Dev(Sec)Ops)26. In secure software development and promoting a security-conscious culture, individual motivation and perception should be considered. The security culture, for example, in open-source software communities, is shaped by the concepts found in above-mentioned theories, the attitudes, behaviors, and skills of the members38. Furthermore, the adoption of secure software practices in companies also relies on individual motivation, backed by organizational support and the ability to learn and adapt16. In small and medium enterprises, factors like the perceived advantages and compatibility with existing practices might also be considered when deciding whether to adopt secure software practices13. Additionally, a supportive community, including social and organizational backing, is essential for encouraging developers to adopt secure coding practices14.

Research model

Literature in the field of cybersecurity awareness suggests a potential association between developers’ understanding of security risks and their behavioral intentions toward secure software engineering (SSE). Information security research has shown that awareness of potential risks significantly influences users’ and developers’ attitudes and intentions toward protective behaviors41,42. In software development contexts, this includes recognizing threats such as injection attacks, misconfigurations, or data leakage. Studies have identified a gap in security-centered programming awareness among developers, which highlights a need for increased focus in this area43,44,45,46. Despite this, risk awareness remains a key precondition for secure behavior. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1

Awareness of risks to developed software is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

Further,42 explored the influence of threat awareness on adopting protective measures, suggesting a positive correlation between awareness and behavioral changes. However, this relationship is not always straightforward, as evidenced by the ”knowing-and-doing” gap in cybersecurity, where awareness does not consistently lead to secure behaviors47. Understanding the relationship between awareness and behavior suggests a complex association that needs more exploration in software development. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H2

Awareness of newest SSE practices is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

The TPB31 proposes predicting factors of individual behavior as attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Various studies have previously applied this theory to predict behavior in SSE11,15,41,48. Within the TPB framework, attitude refers to the degree to which a person evaluates desirable or unfavorable behavior, in this case, secure coding practices48. Research (e.g.,11) has shown that attitude is a strong predictor in TPB, particularly in the domain of SSE, where the tendency to adopt secure practices is (among others) influenced by one’s attitude toward these practices. Additionally, experiences with security issues tend to have a lasting impact on attitudes toward software security43. The latter study indicated that after encountering security issues, most participants acknowledged the importance of software security and implemented specific procedures to address it. This lasting effect of experience on attitude suggests that a positive attitude toward SSE significantly contributes to the intention to engage in secure coding practices. Based on this, we hypothesize:

H3

Attitude toward SSE is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

Subjective norm, as described in the TPB and emphasized by numerous researchers, plays a critical role in shaping behavioral intentions31, including those related to secure software engineering (SSE). These norms represent the perceived social pressure exerted by influential groups or individuals, which can significantly influence a person’s opinions and attitudes48,49. In the context of SSE, the influence of subjective norms has been acknowledged in various behavioral prediction models11,41,48. These norms can be explained by the perception of what significant others think about performing or not performing a behavior41. However, it’s important to note that subjective norm does not always significantly predict behavioral intention42, even though it was proven as a significant predictor of behavioral intention regarding SSE practice11. In work-related issues, especially in SSE, colleagues often serve as important referents, influencing individual behaviors through subjective norm16. Subjective norm is particularly relevant in the field of SSE because they cause collective expectations and pressures within the professional community41. In software development environments, the influence of peers, management, and the broader organizational culture can significantly shape a developer’s approach to secure coding. The adoption of SSE practices is not just a matter of individual skill or awareness but is also influenced by the perceived expectations and norms within the work environment. Based on this, we hypothesize:

H4

Subjective norm is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

When it comes to technology adoption, one of the main theories used in the literature is the Technology Acceptance Model24 and its derivatives, which typically means including the potential ease of use of the technology and its perceived usefulness. In the field of software engineering, especially SSE, the concept of ease of use has not been frequently examined, in contrast to perceived behavioral control, which has been a more common focus11,16,41,48, even though literature suggests a strong association between the two constructs42, where it should be emphasized, that perceived behavioral control refers to the individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty using a technology50 when applying it to the context of adopting new technology. However, ease of use, known as a vital predicting factor in adopting new technologies across various fields25, including engineering51, together with its strong link to perceived behavioral control42, suggests its relevance in SSE. Thus, we build on the premise that if SSE practices and tools are perceived as easy to use, they are more likely to be adopted and integrated into regular development workflows. This is rooted in the assumption that ease of use makes new practices more approachable and plays a similar (even though not exactly the same) role as perceived behavioral control. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H5

Ease of use is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

Together with ease of use, perceived usefulness, another fundamental construct of the TAM24, plays a vital role in predicting the behavioral intention in technology adoption. It is often considered a stronger predictor than ease of use12, and reflects the degree to which developers believe that employing specific security measures or tools will enhance their (task) performance. As such, it is a key driver for their adoption in the domain of security practices11. Additionally, the complexity of security tools, which negatively impacts their perceived usefulness, can discourage their adoption23. The importance of perceived usefulness in encouraging the adoption of security tools and practices is further suggested in studies on SSE43,52. However, the perceived usefulness extends beyond only the functionality of tools and also includes the broader benefits of the software development process itself53. In this context, the perceived usefulness of SSE, which contains both the direct benefits and the perceived advantages of the development process, we hypothesize that perceived usefulness is positively associated with the behavioral intention to adopt and adhere to secure coding practices:

H6

Perceived usefulness is positively associated with behavioral intention to practice SSE.

Research methodology

Research design

This study employed a cross-sectional research design to determine which factors are associated with adoption of SEE practices. A survey was conducted to investigate the determinants of behavioral intention to practice SSE.

Ethical considerations

The study proposal was approved on 8 April 2022 by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Maribor, Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Theoretical constructs were defined and operationalized as presented in Table 1. Questionnaire items were taken from previously validated research and adapted to the context of the study. All theoretical constructs were modeled as first-order reflective constructs. Items for awareness of risks to developed software and awareness of newest SSE practices were adapted from41. Next, items for attitude toward SSE, subjective norm and perceived usefulness were adapted from11. Items for ease of use were adapted from24. Finally, items for behavioral intention were adapted from54. Questionnaire items for awareness of risks to developed software, subjective norm, ease of use and perceived usefulness were measured by using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. Questionnaire items for awareness of newest SSE practices, attitude toward SSE and behavioral intention were measured by using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree. The survey was distributed in English.

Sample and data collection

The sample included 463 people working in software development (e.g., software developers, security experts, project managers). The survey was conducted between 11 and 12 April 2022. Respondents were recruited through the Prolific platform https://prolific.co/. They were presented with an informed consent statement on the first page of the online survey. By proceeding to the survey, they indicated their agreement through implied consent (i.e., by continuing with the survey, they gave their consent through conduct). Respondents received a compensation of GBP 0.43 for taking the survey. A total of 530 respondents took the survey. 30 respondents did not complete the questionnaire or withdrew from the study. 14 responses were excluded for failing an attention check. Next, we excluded 22 respondents with no software development experience. Responses were further checked for indications of respondent non-engagement (i.e., standard deviation equal to 0). After excluding a single response due to respondent non-engagement, we were left with 463 useful responses which were used in further analyses.

Table 2 shows the sample characteristics. Age of the respondents ranged from 19 to 64 years old (\(M=30.5,SD=8.7,median=28\)). Experience with software development ranged from 1 to 36 years (\(M=5.6,SD=6.1,median=3\)). Experience with SSE ranged from 0 to 27 years (\(M=1.7,SD=3.2,median=1\)). A significant share of respondents (\(N_{inexp}=202\)) had no prior experience with SSE. A number of respondents chose a role in software development that did not fit out predefined categories (i.e., Other). These included quality assurance specialists, software testers, AI developers, various leading roles beside project managers, such as team and development leads, software architects, etc. A low share of security experts could be attributed to the fact that few people primarily specialize in security and may consider themselves primarily as some other role in software development even though they have experience with SSE. This is in line with the widely adopted agile methods in which a certain role can be played by several people, and a single person can play several roles55,56. Therefore, we considered experience with SSE as the key indicator of adoption of SEE.

Data analysis

Covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was employed to analyze the data since all measured theoretical constructs were reflective. CB-SEM enables the analysis of complex research models when these include latent variables (i.e., theoretical constructs) with multiple indicators which allow for indirect measurement through characteristics attributed to them. A key advantage of CB-SEM is that it integrates the measurements of latent variables and associations between them into a concurrent evaluation.

Data was analyzed with R version 4.3.2, with lavaan version 0.6-16 and semTools version 0.5-6 packages. Missing values (0.05 percent) were imputed with medians prior to the analysis. When there is less than 10 percent missing values, any imputation method can be applied57. We considered median imputation as adequate since the reduced variance of the distribution and depressed observed variables induced57,58,59 is insignificant considering the relatively few missing data. Model fit of all measurement and structural models was determined with fit indices \(\chi ^2/df\), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Standard thresholds were used to interpret how well the data fit the models ensuring that the results of CB-SEM analysis are meaningful.

To validate the survey instrument, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. Convergent validity was determined by evaluating average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings of items on their corresponding latent variables. Discriminant validity was evaluated with a heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) analysis. Reliability was determined with Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR).

A structural model was developed to test the hypothesized associations. We calculated Cohen’s \(f^2\) for measuring local effect size for each hypothesized association60. This calculation includes the calculation of \(R^2\) change for each association. There are various ways to calculate \(R^2\) change for associations in CB-SEM. We opted to calculate \(R^2\) change by using the direct matrix approach suggested by61 as it enables calculation of \(R^2\) changes for all associations without the need to alter the structural model. We used function rsquareCalc in the provided script to calculate \(R^2\) changes61.

To gain more insights into whether there are differences due to SSE experience, we split our sample into two subsamples. The pre-adoption subsample included respondents without SSE experience (\(N_{pre}=202\)). The post-adoption subsample included respondents with at least one year of SSE experience (\(N_{post}=261\)). First, we aggregated individual item scores into construct item scores by calculating their means. We used independent samples t tests to compare means of measured constructs between the subsamples. Next, we tested the structural model on each subsample to investigate the differences between the two subsamples.

Results

Measurement model

A measurement model was developed to validate the survey instrument. First, we tested the full measurement model. However, an item for awareness of risks to developed software (i.e., AoRtDS3) and perceived usefulness (i.e., PU3) had poor factor loadings and were thus excluded from the measurement model. The fit of the final measurement model presented in Table 3 indicates that the data fits it well.

Table 4 presents CA, CR, AVE and HTMT analysis which are relevant for determining the validity and reliability of the survey instrument. First, CA ranged from 0.705 to 0.953 and CR from 0.710 to 0.954 exceeding the commonly accepted threshold 0.70. This demonstrates adequate reliability of all constructs. Next, AVE ranged from 0.553 to 0.874. Values above the 0.50 threshold are generally considered as acceptable therefore indicating adequate convergent validity. Additionally, all factor loadings (see Table 5) were above 0.50 showing further support for adequate convergent validity. Finally, HTMT ratios of correlations were all below the conservative 0.85 threshold thus indicating adequate discriminant validity of the survey instrument.

Structural model

This subsection presents the results for the full sample. A structural model was developed to test the hypothesized direct effects. Model fit of the structural model is presented in Table 6, and indicates that the model fits the data well.

Effect sizes for the structural model are presented in Fig 1. The predictors explain a meaningful share of variance of behavioral intention (\(R^2=0.617\), \(95\%\) CI [0.563, 0.670]). Significant positive associations between behavioral intention and awareness of newest SSE practices (\(beta=0.237\), \(95\%\) CI [0.139, 0.334], \(p<0.001\)), attitude toward SSE (\(beta=0.306\), \(95\%\) CI [0.171, 0.441], \(p<0.001\)), subjective norm (\(beta=0.249\), \(95\%\) CI [0.157, 0.341], \(p<0.001\)), and ease of use (\(beta=0.111\), \(95\%\) CI [0.022, 0.201], \(p=0.015\)) indicate support for hypotheses H2, H3, H4 and H5, respectively. All these associations had small effect sizes (\(f^2 \ge 0.02\)). The results do not show support for hypotheses H1 (\(beta=0.066\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.030, 0.163]\), \(p=0.178\)) and H6 (\(beta=0.068\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.059, 0.194]\), \(p=0.295\)). The association with control variable age was negative and significant (\(beta=-0.064\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.127, -0.001]\), \(p=0.047\)) albeit with a negligible effect size (\(f^2 <0.02\)).

Experience with SSE

This subsection presents the results for the two subsamples, namely, the pre-adoption and the post-adoption subsamples. First, we conducted independent samples t tests as presented in Table 7.

These test indicate that mean scores in the post-adoption subsample are higher than mean scores in the pre-adoption subsample for all constructs except perceived usefulness. For this construct, the difference was non-significant.

Second, the structural model was tested on the pre-adoption and the post-adoption subsamples. Model fits for both subsamples are presented in Tables 8 and 9. These results suggest that the structural model fits both subsamples well.

Effect sizes for the pre-adoption and post-adoption subsamples are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

The predictors explain a meaningful share of behavioral intention variance for both subsamples (pre-adoption: \(R^2=0.568\), \(95\%\) CI [0.482, 0.653]; post-adoption: \(R^2=0.686\), \(95\%\) CI [0.625, 0.747]). However, none of the associations were significant in both subsamples indicating a major shift in the determinants of behavioral intention from the pre-adoption to the post-adoption phase.

In the pre-adoption subsample, there were significant positive associations between behavioral intention and awareness of risks to developed software (\(beta=0.139\), \(95\%\) CI [0.001, 0.278], \(p=0.049\)), awareness of newest SSE practices (\(beta=0.261\), \(95\%\) CI [0.132, 0.391], \(p<0.001\)), and subjective norm (\(beta=0.416\), \(95\%\) CI [0.292, 0.541], \(p<0.001\)) which shows support for hypotheses H1, H2 and H4, respectively. The associations with awareness of risks to developed software and awareness of newest SSE practices had small effect sizes (\(f^2 \ge 0.02\)) while the association with subjective norm had a medium effect size (\(f^2 \ge 0.15\)). The association between behavioral intention and perceived usefulness was non-significant (\(beta=0.170\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.018, 0.358]\), \(p=0.076\)) however had a small effect size (\(f^2 \ge 0.02\)) thus indicating some support for hypothesis H6. There was no support for hypotheses H3 (\(beta=0.092\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.094, 0.277]\), \(p=0.332\)) or H5 (\(beta=0.049\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.083, 0.181]\), \(p=0.470\)). The association with control variable age was non-significant (\(beta=0.006\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.096, 0.107]\), \(p=0.915\)).

In the post-adoption subsample, there were significant positive associations between behavioral intention and attitude toward SSE (\(beta=0.668\), \(95\%\) CI [0.460, 0.875], \(p<0.001\)), and ease of use (\(beta=0.193\), \(95\%\) CI [0.077, 0.309], \(p=0.001\)) which shows support for hypotheses H3 and H5, respectively. The association with attitude toward SSE had a large effect size (\(f^2 \ge 0.35\)), and the association with ease of use had a small effect size (\(f^2 \ge 0.02\)). The results indicated no support for hypotheses H1 (\(beta=-0.029\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.165, 0.106]\), \(p=0.670\)), H2 (\(beta=0.107\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.028, 0.243]\), \(p=0.121\)), H4 (\(beta=0.042\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.083, 0.167]\), \(p=0.510\)) or H6 (\(beta=-0.059\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.251, 0.133]\), \(p=0.549\)). The association with control variable age was negative and significant (\(beta=-0.122\), \(95\%\) CI \([-0.202, -0.041]\), \(p=0.003\)), and had a small effect size (\(f^2 \ge 0.02\)).

Summary

Table 10 provides a summary of hypothesis testing results.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to study determinants of SSE practices adoption from varying theories and in different adoption phases. It makes a number of contributions to literature on adoption of SEE practices as well as adoption theories in general as presented in the following.

Theoretical implications

This study has several theoretical implications. First, the results of this study indicate that both TPB and TAM explain adoption of SSE practices well albeit they may seem somewhat puzzling at first sight. Positive associations of behavioral intention with attitude toward SSE, subjective norm and ease of use indicate support for TPB. Even though the first two constructs are directly taken from TPB, ease of use (which is conceptually equivalent to effort expectancy29) is used as a replacement for the original TPB construct perceived behavioral control which is interpreted as perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior in several TPB studies, including in the SSE domain11,62. The associations with attitude toward SSE and subjective norm highlight the social and psychological aspects of adoption. A positive attitude toward SSE may originate from personal values or experiences that align with the principles of SSE. The role of subjective norm suggests that the social environment, including the opinions of colleagues and industry peers, plays a significant role in shaping behavioral intentions of individuals. This may be particularly relevant in environments where collaborative decision-making and peer influences are strong, such as in agile software development teams. These results are not fully consistent with11 where self-efficacy was not found to be associated with behavioral intention. This could be a consequence of including ease of use (a TAM construct) instead of self-efficacy (a decomposed TPB construct62) which may indicate a better fit of TAM for explaining this adoption determinant.

The overall support for TAM is however poorer than the support for TPB. Although subjective norm is associated with behavioral intention in the full sample, the third TAM construct, namely perceived usefulness, is not. On one hand, this appears to be consistent with the published TAM literature14. On the other hand, this is not quite consistent with the recent findings from the DOI literature highlighting the importance of relative advantage13 which is the DOI equivalent of perceived usefulness18. We may note that the association between relative advantage and adoption intention was barely significant in that study (\(p=0.049\))13. Therefore, the support for this association is marginal at best in the literature. Interestingly, there is also some marginal support for this association for the pre-adoption subsample. Even though the association between perceived usefulness and behavioral intention is non-significant, it had a non-negligible (i.e., small) effect size. Perceived usefulness has been related to attitude toward behavior in the original TAM24 which may explain why this association is not significant29. These considerations suggest that there may be good reasons to consider adoption from a single theoretical perspective (i.e., either the TPB or the TAM perspective). However, there may be good reasons to consider adoption of SSE practices from an integrated TAM-TPB perspective, too, as explained by the next theoretical implication.

Second, this study advances the field by being among the first to investigate the intentions to practice SSE across different adoption phases. Specifically, the results of our study indicate a shift of significant determinants between the pre-adoption and the post-adoption phase. The interesting part is that neither TPB nor TAM explain adoption of SSE practices well on their own – but very well together, with the addition of new awareness constructs since \(R^2\) ranged from 0.568 in the pre-adoption to 0.686 in the post-adoption phase.

In the pre-adoption subsample, only the association of behavioral intention with subjective norm was significant among TPB and TAM constructs while the association with perceived usefulness was non-significant with a small effect size. The medium effect of subjective norm in the pre-adoption phase highlights the influence of the social environment on initial adoption decisions. Developers might be more inclined to consider adopting SSE practices if they perceive it as a norm or expectation within their professional community (e.g., due to the opinions of peers, organizational culture or industry trends). Although subjective norm is a construct in both theories, these results indicate quite poor support for both TPB and TAM beyond subjective norm.

In the post-adoption subsample, there were significant associations of behavioral intention with attitude toward SSE (i.e., primarily a TPB construct) and ease of use (i.e., primarily a TAM construct). The association between behavioral intention and attitude toward SSE dominates in the post-adoption phase with a large effect size. This suggests that once developers adopt SSE practices their continued practicing may stem from a better understanding and appreciation of the value of SSE practices which develops through hands-on experience. Although having a small effect size, the association between behavioral intention and ease of use may indicate the importance of integrating SSE practices into existing workflows for continuing to practice SSE. Developers are more inclined toward continuing to use SEE practices that they find more straightforward and likely more compatible with their existing routines.

It is interesting to note that there was no overlap in significant determinants between the pre-adoption and post-adoption subsamples. Such differences presumably originate from an individual’s distinct perspectives on SSE practices during different phases of the adoption process. In the pre-adoption phase, individuals form their initial opinions based on the gathered information from their surroundings. Therefore, external factors, such as subjective norm and awareness, may be more meaningful. These factors should be considered in future studies focusing on the pre-adoption phase as well as studies on adoption of SSE practices in general. Other external factors may also play important roles thus future studies may seek to identify them. In the post-adoption phase, individuals adapt their opinions based on their own experience with SSE practices thus factors that are more closely related to them, such as ease of use and attitude toward SSE practices, gain prominence. These factors explain very well the continuance intention therefore future studies may consider them in their research models. This shift between the adoption phases can be therefore considered as a natural progression in the adoption life cycle. These findings also contribute to the broader adoption theory as there may be justifiable reasons to study different adoption phases separately contrary to the long-standing tendency to unify theories of adoption and (continued) use, such as UTAUT29 and its later variants. If adoption of SSE practices is nevertheless studied in a uniform way, relevant constructs from both adoption phases should be included in research models.

Third, this is among the first studies integrating awareness constructs in the research model. The addition of two awareness determinants (i.e., awareness of risks to developed software and awareness of newest SSE practices) provides a broader understanding of adoption of SSE practices. The positive association of behavioral intention with awareness of newest SSE practices indicates that staying updated with the latest advancements is a critical motivator for adopting SSE practices. This may be attributed to the frequently evolving nature of these practices since new threats and solutions emerge continuously. Similarly to TPB and TAM constructs, there were differences between the pre-adoption and post-adoption phase. Both awareness constructs were significant only in the pre-adoption subsample. This suggests that being aware of the potential risks to developed software and being aware of the solution to tackle them are among the key determinants of adoption of SSE practices. However, these factors appear to loose all importance after actually having experience with SSE practices.

Practical implications

The empirical findings of this study also provide some implications for implementing DevSecOps in practice. First, the distinction between influencing factors in different phases of SSE adoption carries significant implications for software development managers. Our study shows that strategies to improve SSE adoption should be tailored to the specific adoption phase of practitioners. Managers should segment their teams into pre-adoption and post-adoption groups and apply targeted interventions that reflect the motivational and cognitive needs of each group. This approach enables more efficient and meaningful promotion of secure software practices.

Second, in the pre-adoption phase, behavioral intention is significantly influenced by developers’ awareness of both the risks to developed software and the newest SSE practices. Managers can take a proactive role by organizing short onboarding sessions, security awareness campaigns, or knowledge-sharing meetups that focus on real-world security incidents (e.g., injection vulnerabilities, authentication failures) and mitigation strategies. They may also provide curated learning materials or internal security newsletters to keep developers up to date with emerging SSE techniques and tools.

Third, shaping subjective norm is also particularly important in the pre-adoption phase. Managers can emphasize the benefits and necessities of compliance with industry standards, protection against rising cybersecurity threats, and alignment with peer and industry expectations. In practice, this may involve integrating secure coding practices into performance expectations, recognizing individuals or teams who demonstrate exemplary security behavior, or having security champions act as internal role models to establish secure behavior as the norm.

Fourth, for practitioners in the post-adoption phase, the focus should shift toward improving user experience and reinforcing positive attitudes toward security practices. Our results show that attitude toward SSE and ease of use are the most influential predictors of continued engagement. Therefore, managers should prioritize developer-friendly security tools and ensure they are well-documented, intuitive, and minimally disruptive to workflows. Collecting feedback from developers on tool usability and involving them in tool selection or configuration can significantly improve adoption.

Fifth, aligning SSE practices with developers’ values and preferences helps cultivate a more favorable attitude. Managers can demonstrate how secure coding reduces long-term rework, improves software maintainability, or supports team efficiency. Cross-functional collaboration with security teams and embedding security into agile activities (e.g., threat modeling in sprint planning) can further improve relevance and perceived usefulness.

Sixth, managers should also highlight the personal benefits of adopting SSE practices. Developers may be more motivated when they see security as a pathway to professional growth. Offering internal certifications or recognizing contributions in promotion and performance reviews can reinforce the value of security knowledge for individual career advancement.

Limitations and future work

This study has some limitations that the readers should note. First, our research model included a limited number of SSE practice adoption determinants. While this approach was necessary to maintain a manageable survey length and minimize respondent fatigue, other relevant determinants may have been excluded from the study. Future studies may thus explore other constructs related to adoption of SSE practices. Second, our study relied on self-reported data. Self-reporting is susceptible to several biases, such as the social desirability bias according to which respondents answer questions in a manner they perceive as more favorable by others. There were some attempts to provide alternative measurement instruments (e.g., self-efficacy63) in the literature. Future studies may therefore employ other research designs and approaches to measure constructs, including observational studies, to provide a more accurate understanding of behaviors and attitudes toward SSE practices. Third, even though the use of the Prolific platform for participant recruitment is widely used in research, it is not without limitations due to potential selection bias. Future studies could expand the sample by employing other channels to reach a broader and more diverse population of software developers. Such an approach would enhance the representativeness of the sample thereby increasing the ecological validity of the findings. Additionally, cross-validation of the results with different sample sources could provide a more robust understanding of the factors associated with the adoption of SSE practices. Such approach would also address the potential limitation of our sample in which only 1.3% of surveyed declared themselves security experts. However, such results need to be interpreted in the broader agile software development context, where each role in the agile team can be done by more than one person, and one team member can do many roles55,56. Thus the 1.3% self-declared security experts are most likely those who in their careers predominantly assume the security expert role, while the rest of the 56.4% of the surveyed respondents who declared their experience with secure software engineering probably encountered the role of the security expert in their careers, even if it is not their preferred or dominant career role. Fourth, our study does not provide any concrete insights into why there are differences between the pre-adoption and post-adoption phases. Future studies, likely involving qualitative research methods, would be necessary to fill in this gap and provide meaningful insights that would further help to first understand the underpinnings of the adoption process and then to develop strategies for improving adoption of SSE practices in the industry. Fifth, we employed a cross-sectional survey design. While such an approach is consistent with prior research on behavioral intentions, it does not allow for causal inferences or the examination of changes over time. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs would therefore be valuable to validate the findings and provide insights into the dynamics of SSE adoption.

Data availibility

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files)

References

IBM. What is devsecops?, (2023).

Amazon. What is devsecops?, (2023).

Microsoft. What is devsecops?, (2023).

RedHat. What is devsecops?, (2023).

International Organization for Standardization. ISO/IEC 15408–1, 2009 (2009).

Poth, Alexander, Kottke, Mario, Middelhauve, Kerstin, Mahr, Torsten & Riel, Andreas. Lean integration of it security and data privacy governance aspects into product development in agile organizations. J. Univ. Computer Sci. 27(8), 868–893 (2021).

Soualmi, A., Laouamer, L. & Alti, A., Performing Security on Digital Images. In Exploring Security in Software Architecture and Design, pages 211–246. IGI Global, (2019).

Türpe, S. & Poller, A. Managing security work in scrum: Tensions and challenges. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings, pages 34–49, (2017).

Ansari, Md Tarique Jamal., Al-Zahrani, Fahad Ahmed, Pandey, Dhirendra & Agrawal, Alka. A fuzzy TOPSIS based analysis toward selection of effective security requirements engineering approach for trustworthy healthcare software development. BMC Med. Inf. Dec. Mak. 20(1), 1–14 (2020).

Bishop, David & Rowland, Pam. Agile and secure software development: An unfinished story. Issues Inf. Syst. 20(1), 144–156 (2019).

Woon, Irene M.Y.. & Kankanhalli, Atreyi. Investigation of is professionals’ intention to practise secure development of applications. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 65, 29–41 (2007).

Lenz, Julia, Bozakov, Zdravko, Wendzel, Steffen & Vrhovec, Simon. Why people replace their aging smart devices: A push-pull-mooring perspective. Computers & Secur. 130(103258), 1–22 (2023).

Umeugo, Wisdom. Factors affecting the adoption of secure software practices in small and medium enterprises that build software in-house. Int. J. Adv. Res. Computer Sci. 14(2), 1–7 (2023).

Sung Kun Kim and Ji Young Kim. Communal antecedents in the adoption of secure coding methodologies. Asia Pacific J. Inf. Syst. 26(2), 231–246 (2016).

Zulfikar Ahmed Maher, Humaiz Shaikh, Mohammad Shadab Khan, Ammar Arbaaeen, and Asadullah Shah. Factors Affecting Secure Software Development Practices among Developers-An Investigation. In 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences, ICETAS 2018, pages 22–23. IEEE, 2018.

Song, Mingqiu, Wang, Penghua & Yang, Peng. Promotion of secure software development assimilation: Stimulating individual motivation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 12(1), 164–183 (2018).

Mathieson, Kieran. Predicting user intentions: Comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2(3), 173–191 (1991).

Blut, Markus, Chong, Alain Yee Loong., Tsiga, Zayyad & Venkatesh, Viswanath. Meta-analysis of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Challenging its validity and charting a research agenda in the red ocean. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 23, 13–95 (2022).

Wagenaar, G., Overbeek, S. & Helms, R. Describing Criteria for Selecting a Scrum Tool Using the Technology Acceptance Model. In Intelligent Information and Database Systems (eds Nguyen, Ngoc Thanh et al.) (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017).

Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of innovations. Macmillian Publishing Co., (1995).

Mahnič, Viljan & Hovelja, Tomaž. The influence of diffusion of innovation theory factors on undergraduate students’ adoption of scrum. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 32(5), 2121–2133 (2016).

Hanslo, R. & Mnkandla, E. Serum adoption challenges detection model: SACDM. In Proceedings of the 2018 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, FedCSIS 2018, number September 2018, pages 949–957. Polish Information Processing Society, (2018).

Witschey, J., Xiao, S. & Murphy-Hill, E. Technical and personal factors influencing developers’ adoption of security tools. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2014-Novem(November):23–26, (2014).

Davis, Fred D., Bagozzi, Richard P. & Warshaw, Paul R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 35, 982–1003 (1989).

Venkatesh, Viswanath & Davis, Fred D. Theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 46(2), 186–204 (2000).

Masombuka, T. & Mnkandla, E., A DevOps collaboration culture acceptance model. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, pages 279–285, (2018).

Overhage, S. & Schlauderer, S. Investigating the long-term acceptance of agile methodologies: An empirical study of developer perceptions in Scrum projects. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pages 5452–5461. IEEE, (2012).

Legris, Paul, Ingham, John & Collerette, Pierre. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 40(3), 191–204 (2003).

Venkatesh, Viswanath, Morris, Michael G., Davis, Gordon B. & Davis, Fred D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly 27(3), 425–478 (2003).

Venkatesh, Viswanath, Thong, James Y. L. & Xin, Xu. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly 36(1), 157–178 (2012).

Ajzen, Icek. The theory of planned behavior. Organiz. Behav. Human Decision Process. 50(2), 179–211 (1991).

Saeidi, Soheila, Enjedani, Somayeh Nazari, Behineh, Elmira Alvandi, Tehranian, Kian & Jazayerifar, Seyedalireza. Factors affecting public transportation use during pandemic: an integrated approach of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Tehnički glasnik 18(3), 342–353 (2024).

Rahi, Samar. What drives citizens to get the covid-19 vaccine? the integration of protection motivation theory and theory of planned behavior. J. Social Market. 13(2), 277–294 (2023).

Rahmat, Taufik Edi et al. Nexus between integrating technology readiness 2.0 index and students’e-library services adoption amid the covid-19 challenges: implications based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Educ. Health Promotion 11(1), 50 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Factors influencing university students’ behavioral intention to use generative artificial intelligence: Integrating the theory of planned behavior and ai literacy. Int. J. Human-Computer Interact. 41(11), 1–23 (2024).

Ajzen, Icek. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior (Dorsey Press, Chicago, 1988).

Amin, A., Rehman, M., Basri, S. & Hassan, M.F. A proposed conceptual framework of programmer’s creativity. In 2nd International Symposium on Technology Management and Emerging Technologies, ISTMET 2015 - Proceeding, pages 108–113. IEEE, (2015).

Wen, S.F., Kianpour, M. & Kowalski, S. An empirical study of security culture in open source software communities. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ASONAM 2019, number August, pages 863–870, (2019).

Guardado, Deana. Process Acceptance and Adoption by IT Software Project Practitioners. PhD thesis, Capella University, School of Business and Technology, (2012).

Masombuka, Koos Themba. A Framework for a Successful Collaboration Culture in Software Development and Operations (DevOps) Environments. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa, (2020).

Safa, Nader Sohrabi et al. Information security conscious care behaviour formation in organizations. Computers & Security 53, 65–78 (2015).

Dinev, Tamara & Qing, Hu. The centrality of awareness in the formation of user behavioral intention toward protective information technologies. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 8(7), 386–408 (2007).

Assal, H. & Chiasson, S. ’Think secure from the beginning’: A Survey with Software Developers. In Computer-Human Interaction 2019, pages 1–13, Glasgow, (2019).

Patel, S. 2019 Global Developer Report: DevSecOps finds security roadblocks divide teams, (2019).

Tahaei, M. & Vaniea, K. A Survey on Developer-Centred Security. Proceedings - 4th IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops, EUROS and PW 2019, (Table I):129–138, (2019).

Schneier, B. Software Developers and Security, (2019).

Ngoqo, Bukelwa & Flowerday, Stephen V. Exploring the relationship between student mobile information security awareness and behavioural intent. Inf. Computer Secur. 23(4), 406–420 (2015).

Jalali, Foad, Nia, Mehran Alidoost, Ermakova, Tatiana, Abdollahi, Meisam & Fabian, Benjamin. Investigating the role of usable security in developers’ intention toward security enhancement in service-oriented applications. Security and Privacy 5(2), 1–21 (2021).

Ajzen, Icek. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2(4), 314–324 (2020).

Zolait, Ali Hussein Saleh. The nature and components of perceived behavioural control as an element of theory of planned behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 33(1), 65–85 (2014).

Cervera, Mario, Albert, Manoli, Torres, Victoria & Pelechano, Vicente. On the usefulness and ease of use of a model-driven Method Engineering approach. Inf. Syst. 50, 36–50 (2015).

Gasiba, T., Lechner, U. & Pinto-Albuquerque, M. Cybersecurity challenges for software developer awareness training in industrial environments. In Innovation Through Information Systems Springer International Publishing (eds Ahlemann, Frederik et al.) (Cham, 2021).

Gefen, David & Keil, Mark. The impact of developer responsiveness on perceptions of usefulness and ease of use: An extension of the technoiogy acceptance model. Data Base for Adv. Inf. Syst. 29(2), 35–49 (1998).

Hossain, Akram, Quaresma, Rui & Rahman, Habibur. Investigating factors influencing the physicians’ adoption of electronic health record (ehr) in healthcare system of bangladesh: An empirical study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 44, 76–87 (2019).

Anwer, Faiza, Aftab, Shabib, Waheed, Usman & Muhammad, Syed Shah. Agile software development models tdd, fdd, dsdm, and crystal methods: A survey. Int. J. Multidisc. Sci. Eng. 8(2), 1–10 (2017).

Al-Saqqa, S., Sawalha, S. & AbdelNabi, H. Agile software development: Methodologies and trends. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 14(11), (2020).

Hair, Joseph F., Black, William C., Babin, Barry J. & Anderson, Rolph E. Multivariate Data Analysis (Prentice Hall, Always learning, 2010).

Allison, Paul D. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. J. Abnormal Psychol. 112(4), 545–557 (2003).

Lateef Babatunde Amusa and Twinomurinzi Hossana. An empirical comparison of some missing data treatments in PLS-SEM. PLOS ONE 19(1), 1–14 (2024).

Selya, Arielle S., Rose, Jennifer S., Dierker, Lisa C., Hedeker, Donald & Mermelstein, Robin J. A practical guide to calculating cohen’s \(f^2\), a measure of local effect size, from proc mixed. Front. Psychol. 3(111), 1–6 (2012).

Hayes, Timothy. R-squared change in structural equation models with latent variables and missing data. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 2127–2157 (2021).

Vrhovec, Simon, Bernik, Igor & Markelj, Blaž. Explaining information seeking intentions: Insights from a Slovenian social engineering awareness campaign. Computers Secur. 125(103038), 1–12 (2023).

Votipka, Daniel, Abrokwa, Desiree, & Mazurek, Michelle L. Building and Validating a Scale for Secure Software Development Self-Efficacy. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, (2020).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and S.V. conceptualised the research, S.V. collected and analysed the results, A.M. wrote the original draft, T.H. contributed to the discussion of the results. All authors reviewed the work of others and finalized the manusript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mihelič, A., Hovelja, T. & Vrhovec, S. Factors influencing the adoption of secure software engineering practices in pre-adoption and post-adoption phases. Sci Rep 15, 42763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27024-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27024-7