Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate notable biological activities and medical applications of Sapindus mukorossi (S. mukorossi) seed hydrosol in wound healing. In this study, S. mukorossi hydrosol (SMH) was prepared and tested for antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and tissue repair activity. Phytochemical analysis using GC–MS revealed SMH to contain two bioactive components, benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl), and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP). Antibacterial testing showed that SMH powder diluted with water at a ratio of 1:2 (SMH 1:2) reduced S. aureus colony counts by 60% (p < 0.05). In vitro viability assays on CCD-966SK fibroblasts demonstrated enhanced cell survival under serum-free conditions, with SMH 1:2 yielding the most sustained effects. Scratch assays confirmed that SMH 1:2 promoted fibroblast migration and significantly accelerated wound closure at 24 and 48 h (p < 0.05). Anti-inflammatory testing showed that SMH 1:2 reduced LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 cells (p < 0.01). In vivo wound healing in rats indicated that SMH 1:2 improved epithelial recovery, resulting in significantly smaller wound areas compared to control on day 14 (8.25% ± 3.85% vs. 14.04% ± 3.50%, p < 0.05). Histological examination confirmed enhanced re-epithelialization in SMH-treated wounds. These findings indicate that S. mukorossi hydrosol holds promise as both a wound-healing agent and an ingredient for use in skincare product development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sapindus mukorossi (S. mukorossi), commonly known as the soapnut tree, belongs to the family Sapindaceae and is widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions from Japan to India. This tree holds significant economic value1,2,3, with a fruit that is especially notable for having a high concentration of triterpenoid saponins (approximately 10.1%) within the pericarp3, which have been traditionally utilized as natural surfactants and cleansers for the body, hair, and textiles1,2,4,5,6. The genus Sapindus encompasses more than 40 known wild species6, with S. mukorossi emerging as a focus of increasing scientific interest due to its broad range of biological and pharmacological properties.

The application of S. mukorossi (Wu Huan Zi in Chinese) seed kernel for antimicrobial and skin care was recorded in China’s traditional pharmacopia, Compendium of Materia Medica (or Bencao Gangmu in Mandarin), some 500 years ago. Notably, the saponin-rich fruit pericarp has demonstrated antimicrobial properties7 and has been traditionally employed in the treatment of skin conditions such as eczema3,8. Several parts of S. mukorossi exhibit bioactive properties. For example, recent reports have indicated that extract from leaves, flower, and fruit pericarp of S. mukorossi exhibit anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties, and suggest that S. mukorossi can be used for wound treatment and cosmetic skin care9,10. However, S. mukorossi seeds are considered inedible and are often discarded as agricultural waste1,11,12, though some studies have explored the seeds’ high oil content for biodiesel production11,13,14. More recently however, a growing body of evidence has revealed that the seed kernel oil possesses notable biomedical properties; specifically in studies demonstrating improved bone growth15,16,17, stabilization of oral microbiota18, and accelerated healing of skin wounds19. These benefits are primarily attributed to anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities that support tissue regeneration and repair19,20,21. Recent reports have also indicated that S. mukorossi seed oil is rich in phytosterols and arachidonic acid19. Phytosterols, such as β-sitosterol, are known for their anti-inflammatory properties which effectively attenuated epidermal hyperplasia and immune cell infiltration22,23. Arachidonic acid is an essential polyunsaturated fatty acid in the skin that plays a crucial role in modulating inflammatory responses24,25. Given that cold-pressed S. mukorossi seed oil exhibits both anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, it has been proposed as a promising candidate for skin care applications19.

However, most of the active compounds in plants, such as polyphenols with antioxidant properties or antimicrobial tannins, are water-soluble and do not dissolve in oils26,27,28. Oils require emulsification or solvent pre-treatment and may have a greasy texture and distinct odor, while aqueous solutions are milder in nature, less likely to irritate skin, and do not clog pores. Aqueous solutions are thus more suitable than oils for formulations such as toners, sprays, and dressings, and are ideal for baby care products and applications involving mucosal or oral tissues. In general, water-based products have greater potential for practical applications29,30.

Steam distillation of essential oils from various parts of plants, including flowers, leaves, fruits, roots, and bark results in an aqueous hydrosol byproduct31,32,33 that contains numerous medicinal properties and the water-soluble components34. Such plant hydrosols often contain a variety of bioactive compounds such as alkaloids, terpenes, and polyphenols35,36, with many studies reporting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, astringent, analgesic, skin-softening, pigment-reducing, moisturizing, and wound-healing properties30,37,38.

Although S. mukorossi seeds have been reported to possess beneficial skin-repairing properties, no studies to date have reported on the use of aqueous S. mukorossi seed extract. The goal of this study was to prepare a hydrosol from S. mukorossi seeds and evaluate its properties related to skin care. This first report in the literature on the application of the aqueous extract of S. mukorossi seeds for skin care may serve as a reference for future medical applications.

Results

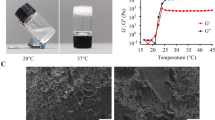

GC–MS phytochemical analysis of S. mukorossi seed hydrosol (SMH) revealed a total of 34 peaks within 30 min (Fig. 1a). The ten predominant compounds were all long-chain alkanes (Table 1), which accounted for a total of 38.67% of the sample. After excluding compounds with mass spectra at 207 m/z and 281 m/z due to siloxane contamination39 and long-chain compounds, two compounds with potential bioactivity were identified at retention times of 9.3 min (Fig. 1b) and 12.0 min (Fig. 1c). Mass spectrometry showed that the 9.3-min peak accounts for 0.47% of the total area, with notably high ion peaks at 175 m/z and 190 m/z. The high m/z peak accompanied by lower-intensity fragments at lower m/z values suggests the presence of a structurally stable functional group most likely associated with a cyclic or polycyclic molecular framework. A search of the literature indicated that this mass ion signature matches Precocene I (6,7-dimethoxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene) and benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl). The compound at RT 12.0 min accounts for 0.86% of the total area, with fragment ions at m/z 206 and m/z 191. A literature search indicated a match with 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP) (Phenol,2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-).

The antibacterial activity of SMH against S. aureus was concentration-dependent (Fig. 2a–d). The PBS control group yielded an average of 171.3 ± 21.1 CFU, while SMH at 1:2 dilution (SMH 1:2) significantly reduced bacterial survival to 69 ± 43 CFU (p < 0 0.05), corresponding to a 60% reduction. Dilutions of 1:4 and 1:8 resulted in 139.7 ± 18.0 CFU and 133 ± 11.1 CFU, equating to 18% and 22% reductions, respectively, but these reductions were not statistically significant (p = 0.120 and 0.068, respectively) compared to the control (Fig. 2e). These results suggest that the antibacterial effect of SMH is concentration-sensitive and optimally effective at higher dosages.

Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus following exposure to (a) PBS (control) and SMH at various dilutions: (b) 1:2, (c) 1:4, and (d) 1:8. (e) The bar graph shows the mean colony-forming units (CFU) of Staphylococcus aureus after 5 min. Only the 1:2 SMH dilution exhibited a significant reduction in bacterial count compared to PBS. (Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences, p < 0.05).

The effect of SMH at various dilutions (1:2, 1:4, and 1:8) on CCD-966SK cell viability was assessed over a 5-day period (Fig. 3). On day 1, all SMH-treated groups exhibited significantly higher absorbance values compared to the SMH-free control, indicating improved initial cell viability in the presence of SMH in the culture medium (p < 0.01). The viability of control cells (cultured in medium without FBS and SMH) increased from day 0 to day 2 but subsequently declined due to the absence of serum. A significant reduction was observed from 0.176 ± 0.008 (day 2) to 0.011 ± 0.009 (day 5) (p < 0.05). In contrast, cells treated with SMH showed a continued increase in viability up to day 4. Notably, the 1:2 dilution group exhibited a steady rise in absorbance from 0.109 ± 0.007 (day 1) to 0.240 ± 0.001 (day 3), and maintained a relatively high level of viability on day 5 (0.216 ± 0.010), with no statistically significant difference compared to day 3. By day 5, all SMH-treated groups exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in viability (p < 0.05), yet their values remained significantly higher than those of the serum-free control (p < 0.01). These findings suggest that SMH supports cell survival under nutrient-deprived conditions and that higher concentrations offer more sustained protective effects. Since the 1:2 dilution showed the best results in terms of cell viability and antibacterial activity (Fig. 2), subsequent in vivo and in vitro wound healing experiments were conducted using SMH at a 1:2 dilution (SMH 1:2).

Quantitative analysis of wound closure revealed a significant difference between SMH 1:2-treated cells and the control group at day 1. In the control group, the wound edges remained intact and noticeable cell death was observed due to serum-free culture conditions. In contrast, cells treated with SMH 1:2 showed clear morphological changes, including the alignment of leading-edge cells toward the wound area and an unclear wound border. Furthermore, a greater number of migrating cells were observed at the scratch margins in the SMH 1:2 group compared to the control (Fig. 4a). Quantitative measurement showed that the wound width in the SMH 1:2-treated cells was significantly reduced to 74.83% (p < 0.05), representing a 0.89-fold decrease relative to the control (83.74%) (Fig. 4b). By day 2, SMH 1:2-treated CCD-966SK cells exhibited significantly enhanced migration into the wound area. Wound width significantly reduced to 53.47% (p < 0.001) in the treated group, whereas the control group retained a wound width of 71.43%, which is 1.34 times wider than that of the SMH 1:2-treated cells (Fig. 4b).

Effect of S. mukorossi seed hydrosol on the in vitro scratch test using CCD-966SK cells during a two-day culture period, original magnification × 40. (a) Cells in the control group exhibited cell death after 1 day due to the serum-free culture environment (blue arrows). With co-culture with SMH 1:2, leading cells at the wound edge oriented toward the wound area 1 day after the scratch trauma was created (red arrows). (b) Scratch-width percentage calculated after quantifying scratch assay images from 0, 1, and 2 days after incubation. The mean value of each group was normalized with the day 0 sample. (Data are presented as mean ± SD. * and ** represent p values lower than 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.)

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory effect of the SMH 1:2, nitric oxide (NO) production was measured in RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). As shown in Fig. 5, LPS stimulation significantly increased NO levels by 3.80-fold, compared to the untreated control (DMEM). Treatment with L-NAME, a known nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, suppressed NO production by 1.26-fold compared to control cells. Notably, co-treatment with SMH 1:2 extract reduced LPS-induced NO production to 3.09-fold, showing a statistically significant decrease compared to the LPS-induction group (p < 0.01).

The in vivo wound healing activity of the prepared S. mukorossi seed hydrosol (SMH 1:2) is presented in Fig. 6. During the initial 6 days post-injury, both the SMH-treated and control groups exhibited hyperemic wound areas with clearly defined borders in the original rectangular wound shape. No visible differences in wound appearance were observed between the two groups during this period (Fig. 6a). By day 10, wound morphology had changed in both groups, with both losing their original geometric shape. Nevertheless, wounds treated with SMH 1:2 displayed drier wound beds with no observable exudate compared to the control group. Despite these visual improvements, quantitative analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in wound area between the two groups within the first 10 days of treatment (Fig. 6b). On day 14, wound beds in the control group also showed dryness and absence of hyperemia. The appearance of the untreated wounds, characterized by a brown color and dryness, was similar to that of the SMH-treated wounds. However, SMH-treated wounds exhibited complete re-epithelialization, and most of the wound area was covered by newly grown hair. At this time point, the average remaining wound size in the SMH-treated group was 8.25% ± 3.85%, which was significantly smaller than that of the control group (14.04% ± 3.50%) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6b).

Based on the histological images shown in Fig. 7a, tissue observation on day 14 reveals that the SMH 1:2-treated group exhibited significantly greater epidermal tissue regeneration at the wound site (Fig. 7d) compared to the control group treated with PBS (Fig. 7c). In the SMH 1:2-treated group, a thicker and more continuous epidermal layer was observed, as indicated by red arrows. The regenerated epithelium appears well-organized and multilayered, suggesting active re-epithelialization (Fig. 7d). In contrast, the control group displayed a thinner and less complete epidermal structure (Fig. 7b).

(a) Histological analysis of wound tissue sections on days 6 and 14 after treatment with PBS or SMH. Blue arrows indicate the original epidermal layer at the wound edges. Red arrows highlight newly formed epidermis covering the wound bed. On day 14, SMH-treated wounds show a greater extent of re-epithelialization compared to the PBS control group as evidenced by the presence of more continuous and thicker newly generated epidermal tissue (red arrows). (b), (c) and (d) are magnified images of un-healed tissue (black rectangle), original epidermal layer (blue rectangle) and newly formed epidermis (red rectangle). Scale bar = 2.5 mm.

Discussion

S. mukorossi seed oil has been shown to promote skin regeneration and wound healing, due to high levels of unsaturated fatty acids, β-sitosterol, and δ-tocopherol that contribute to bioactivity. In vitro studies have also demonstrated that S. mukorossi seed oil contributes to enhanced fibroblast proliferation and anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing nitric oxide in LPS-stimulated macrophages. In vivo, topical application of the seed oil accelerated wound closure in rats, whose wounds were significantly smaller when observed by day 8 compared to controls19. Although S. mukorossi seed oil contains various bioactive components that promote skin regeneration, its oily nature may limit practicality in daily skincare applications, particularly in situations requiring frequent application or for individuals who prefer non-greasy formulations.

Recent investigations highlighting the therapeutic efficacy of various plant-derived hydrosols in dermatological applications, particularly for skin care and wound healing, have concluded that the beneficial effect of plant hydrosols for medical and cosmetic applications depends on the plant species, the plant’s origin, and the part of the plant from which the hydrosol was obtained35. In the present in vitro experiments, a hydrosol derived from S. mukorossi seed kernels demonstrated anti-bacterial (Fig. 2) and anti-inflammatory (Fig. 5) properties, enhanced skin cell viability (Fig. 3), and wound healing (Fig. 4) effects. These results support the in vivo animal experiments (Figs. 6, 7), indicating that SMH is beneficial for skin wound healing.

Another potential application of plant extracts lies in their use as natural materials for green nanotechnology approaches40,41,42,43. In recent years, plant extract–conjugated nanoparticles have attracted growing interest in biomedical, pharmaceutical, and environmental fields. Studies have reported that seed extracts can conjugate with silver and gold nanoparticles, thereby enhancing their anticancer efficacy40,41. In addition, leaf extracts from various plants can also be used to modify nanoparticles, improving their wound-healing properties42,43.

To identify the major bioactive constituents in SMH, a compositional analysis using GC–MS was conducted (Fig. 1). The ten most prominent compounds identified are all long-chain alkanes (Table 1), similar to the components usually found in plant extracts. These long-chain alkanes have been reported to have antibacterial and antioxidant activities44,45. For instance, dodecane has been reported to possess antioxidant activity46, while tetradecane exhibits antimicrobial properties47, while both hexadecane and tetracosane have demonstrated dual antimicrobial and antioxidant activities48,49.

In addition to long-chain alkanes, two bioactive aromatic hydrocarbons were identified at retention times of 9.313 min (Fig. 1b) and 12.057 min (Fig. 1c). There are two possible compounds that exhibit high match scores of the mass spectrum at the RT 9.313 min peak, Percocene I and benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl). Precocene I is a phytochemical predominantly isolated from members of the family Asteraceae, which encompasses angiosperms such as daisies and sunflowers50. This compound exhibits diverse biological properties, notably as an insecticidal agent against a wide range of insect species that is particularly efficacious during the antijuvenile phase of the developmental cycle51,52,53. However, although a high degree of similarity was observed in the relative intensities of the m/z 175 and m/z 190 peaks to the NIST Mass Spectral Library (NIST Chemistry WebBook, https://webbook.nist.gov/), the m/z 57 ion was not observed (Fig. 1b). A more likely candidate corresponding to the m/z 57, 175, and 190 ions is benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) (C14H22) (NIST Chemistry WebBook, https://webbook.nist.gov/). The peak at m/z 175 is plausibly formed due to the cleavage and subsequent loss of a methyl group following ionization, while m/z 57 comes from the tert-butyl cation (C4H9+) of the compound (Fig. 8a). This compound is primarily a synthetic chemical, but is occasionally found in natural sources such as flower extracts from Paracoccus pantotrophus45 and Iris kashmiriana54. Interestingly, several reports have indicated that this compound provides significant antibacterial activity45,47,54.

Figure 1c shows the compound at a retention time of 12.057 min is a derivative of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP). A 2,4-DTBP derivative is the more plausible candidate, as the spectrum shows a characteristic base peak at m/z 191 accompanied by a prominent m/z 206 peak (NIST Chemistry WebBook, https://webbook.nist.gov/) which is in agreement with previous literature44,55,56,57. This compound may correspond to 2,4-DTBP itself (Fig. 8b), in which case the m/z 206 peak would represent its molecular ion. Alternatively, it may be a structural derivative such as 2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl 5-hydroxypentanoate55, wherein the m/z 206 peak arises from the loss of the 5-hydroxypentanoate moiety yielding a DTBP-related fragment ion at m/z 206 and m/z 191.

2,4-DTBP and its derivatives have been reported to exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antibacterial properties54,55,56,57,58,59. 2,4-DTBP itself is a lipophilic phenolic compound classified as a natural product and secondary metabolite that occurs naturally in various plants59,60. Its derivatives, such as 2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl 5-hydroxypentanoate, are most commonly found in Benincasa hispida (Cucurbitaceae family) seed extract55. Detecting this compound in the hydrosol extracted from S. mukorossi seed kernel is consistent with its known natural sources.

Secondary metabolites are organic compounds produced by living organisms, and in plants often function as part of the plant’s defense mechanism against herbivory61. In general, plant-derived secondary metabolites, particularly phenolic compounds including 2,4-DTBP, have been demonstrated to possess antibacterial properties and the potential to reduce antibiotic resistance while maintaining low cytotoxicity62. The most likely mechanism of the antimicrobial action of S. mukorossi seed hydrosol seen in Fig. 2 is the 2,4-DTBP content, as 2,4-DTBP is a potent antimicrobial agent49,58.

Wound healing is a complex, multistep physiological process that encompasses the regulation of inflammation, cellular proliferation, and tissue remodeling. The inflammatory phase represents the initial and essential response following tissue injury, and serves as a critical foundation for subsequent healing events. As presented in Fig. 5, the addition of SMH markedly reduced nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophage cells. This observation aligns with previous findings from a skincare study utilizing S. mukorossi seed oil19, which identified β-sitosterol as a principal bioactive compound contributing to the observed anti-inflammatory effects. Nonetheless, β-sitosterol is a phytosterol with extremely low aqueous solubility, and as such is unlikely to be present in the SMH preparation used in the current study. The anti-inflammatory effects of 2,4-DTBP have been previously evaluated using an LPS-induced inflammation model in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. In that study, treatment with 2,4-DTBP significantly downregulated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β60. In 2024, Rouvier et al. also identified 2,4-DTBP as the principal bioactive constituent of propolis. Their study provided both in vitro and in vivo evidence demonstrating that 2,4-DTBP not only effectively suppresses the overgrowth of Cutibacterium acnes but also exhibits notable anti-inflammatory properties56.

Cellular proliferation and migration play pivotal roles in re-epithelialization and the remodeling of skin tissue throughout the wound healing process63. The results shown in Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate that CCD-966SK cells cultured in vitro undergo significant cell death after 2 days due to the lack of nutrient supply. This phenomenon indicates that SMH not only promotes CCD-966SK cell proliferation (Fig. 3) and migration (Fig. 4), but can also delay the decrease in cell viability caused by starvation. Similar healing effects were also observed in the artificial wounds in the rat model (Figs. 6, 7). These results indicate that SMH 1:2 treatment can enhance epidermal regeneration at the wound site and potentially improve the overall wound healing process. However, the phytochemical analysis conducted in this study (Fig. 1) did not identify any compounds that promote skin cell proliferation. The observed reduction in cell viability loss under starvation conditions when co-cultured with SMH may be attributed to undetected nutritional compounds present in SMH. The inability of GC–MS analysis to detect compounds with a molecular weight larger than 400 Da is a limitation of this study. In addition, because the animal study did not include Masson’s trichrome staining or molecular markers of wound healing, the present study cannot provide information regarding collagen status at the wound site. This limitation restricts discussion of the wound-healing mechanism associated with the application of SMH.

Conclusions

This study is the first to demonstrate that S. mukorossi seed hydrosol exhibits significant antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity as well as the ability to stimulate skin cell proliferation and migration. Bioactive aromatic hydrocarbons, particularly 2,4-DTBP, present in the phytochemical composition of SMH are key contributors to the hydrosol’s beneficial effects. Based on these findings, we propose that S. mukorossi seed hydrosol is a promising candidate for natural skin care applications.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

N-nitro-l-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME), Griess reagent, hematoxylin and eosin staining kit and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), Fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin-EDTA, L-glutamine, and penicillin and streptomycin were obtained from HyClone (South Logan, UT, USA). A tetrazolium salt ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, MTT) kit was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany). Nutrient broth was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

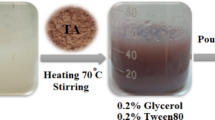

S. mukorossi seeds hydrosol preparation

The S. mukorossi seeds were purchased from He–He Co. Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan). Before hydrosol preparation, the seeds were cleaned under running tap water followed by rinsing with sterile distilled water, and dried in an oven at 40 °C for 72 h. The intact seeds including kernel and shells were ground in a pulverizer to pass a 0.5 mm pore-size screen as previously reported64.

The hydrosol from S. mukorossi seeds was obtained using the hydro-distillation technique. Seed powder was placed into a 2 L round-bottom flask along with 400 mL of distilled water, with plant material fully submerged. The plant material was then subjected to hydro-distillation using a rotary evaporation device (OSB-2100, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 9). The powder-to-water mixing ratios were set at 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8 (w/w). The samples were heated to 40 °C in vacuum environment. The distillation process was carried out for approximately 3 h. Volatile components carried by the steam were condensed through a water-cooled condenser and collected in the receiving flask. The aqueous phase was collected as hydrosol samples (SMH). After filtering through a 0.22 µm membrane filter, the collected samples were stored at 4 °C until bioactivity testing.

Preparation of S. mukorossi seed hydrosol. (a) Fruit and seeds of S. mukorossi were collected. (b) Seeds were dried and ground into a fine powder. (c) The seed powder was mixed with water and subjected to steam distillation to produce a hydrosol containing bioactive volatile compounds. The essential oil was separated and collected.

Phytochemical analysis of S. mukorossi seeds hydrosol

The prepared SMH was filtered and used for phytochemical analysis. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent 7820A gas chromatograph coupled with an Agilent 5977 mass series selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). GC–MS conditions were modified from a previous phytochemistry analysis65. An HP-5MS (Agilent Technologies, USA) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness) was used for separation. Helium was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The temperatures of the ion source and injection port were set at 230 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was programmed from 50 to 285 °C at an increasing rate of 2 °C/min with a total run time of 30 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in the electron impact (EI) mode at 70 eV. Two samples with a volume of 1μL were injected into the Agilent GC system; distilled water was set as the background sample, and the prepared SMH was used as the testing sample. The resulting data from the testing samples were compared to the background sample to eliminate compounds from the solvent. Data was collected with the Agilent Mass Hunter software (Agilent Technologies, USA). For identification of the analyzed constituents with various retention times, library searches of mass spectra were performed using both the National Institute Standard and Technology Mass Spectral Library (NIST20, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and the Wiley Library (Hoboken, NJ, USA). Mass spectra consistent with linear hydrocarbons were excluded from analysis. Emphasis was placed on compounds exhibiting base peaks—those with the highest relative intensity—at higher mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios, as such features are indicative of structurally stable functional groups associated with high molecular weight compounds. Possible bioactive compounds in the tested SMH were identified through selective targeting of molecules containing cyclic or polycyclic functional groups.

Antibacterial activity test against Staphylococcus aureus

The antibacterial efficacy of SMH against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, ATCC 6538) was assessed using a quantitative suspension test. The bacteria were cultured in nutrient broth at 35 °C for 24 h, harvested by centrifugation. Then, the samples were diluted 1000-fold and resuspended in the PBS. 10μL equal volume of bacterial suspension was mixed with 1 mL SMH at various dilutions (1:2, 1:4, and 1:8, w/w). After a 5-min contact time at 35 °C, the mixtures were plated on nutrient agar in triplicate. Colonies were counted after 24-h incubation at 37 °C and compared with PBS-treated controls.

In vitro cell proliferation assay

To evaluate the proliferative effect of prepared S. mukorossi seed hydrosol on skin cells, a cell viability assay was conducted. The human skin fibroblast cell line CCD-966SK (ATCC CRL-1881) was used for in vitro analysis. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/mL and cultured in αMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× sodium pyruvate and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, then incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After allowing 1 day for cell attachment, the medium was replaced with FBS-free αMEM for one additional day to induce starvation. Subsequently, the cells were treated with SMH medium (prepared at dilutions of 1:2, 1:4 and 1:8) and incubated for 5 days. When preparing a standard medium, the ratio of double distilled (DD) water to medium powder is 9:1 (w/w). SMH was used instead of DD water to prepare SMH medium in this study. Cell viability was assessed using the tetrazolium salt (MTT) method. After a 4-h incubation with the tetrazolium salt, 500 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals for 5 min. Optical density was measured at 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 690 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). Based on the results showing that the 1:2 dilution exhibited the most favorable antibacterial (Fig. 2) and cell viability effects (Fig. 3), both this scratch assay and subsequent in vivo wound healing experiments were conducted using S. mukorossi seed hydrosol at a 1:2 dilution (SMH 1:2). All the cellular experiments were performed in triplicate.

In vitro scratch wound healing test

The effect of SMH on cell migration and wound healing activity was evaluated using an in vitro scratch assay. CCD-966SK human skin fibroblasts were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/mL in 24-well culture plates and incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Once the cells reached confluence, they were serum-starved overnight as described above. A linear scratch was then created at the center of each well using a 200-μL pipette tip. Detached or non-adherent cells were removed by washing with fresh serum-free medium. Following this, cells were treated with SMH (1:2) medium. Cells maintained in serum-free medium without hydrosol served as the control group. Bright-field images were acquired using a microscope (Eclipse TS100, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (SPOT Idea, Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA) at 4 × magnification. Photographs were taken immediately after scratching (day 0), and again after 1 and 2 days of incubation, capturing five random fields per wound area. All cellular experiments were performed in triplicate.

Anti-inflammatory experiment

To evaluate the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of the prepared SMH, a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation model using RAW 264.7 macrophage cells was employed. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 4 × 105 cells/mL and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 24 h of pre-incubation, cells were pretreated with SMH (1:2) medium for 24 h. Subsequently, inflammation was induced by adding LPS (1 μg/mL) derived from Escherichia coli strain O55:B5, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 1 mM) was used as a positive control. The concentration of nitric oxide (NO) produced by the cells was quantified using the Griess reagent assay. Briefly, an equal volume of Griess reagent was mixed with the culture supernatant, and color development was measured at 530 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). Anti-inflammatory activity was presented in terms of NO production percentage. The NO release of the samples was normalized by comparing the measured data to the untreated samples. All cellular experiments were performed in triplicate.

In vivo wound healing activity test

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing between 200 and 300 g were used to evaluate the wound healing effects of SMH 1:2. The animals were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the National Applied Research Laboratories (Hsinchu, Taiwan) and housed in clean individual cages with a 12-h light/dark cycle, ambient temperature of 21 °C, and relative humidity maintained between 60 and 70% for the duration of the experimental period. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Leo Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan (IACUC Approval No. L10708) and performed and reported in accordance with the Taiwan law on animal welfare and under consideration of the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). Every effort was made to minimize the number of animals used and reduce animal distress while ensuring scientific integrity and reliability.

The wound healing experiment was conducted following the methodology described in a previous study19. Prior to the procedure, a 5 × 5 cm area on the dorsal surface of each rat was shaved using an electric animal clipper and disinfected with 75% ethanol. Anesthesia was induced using 5% isoflurane in an induction chamber to ensure the animals were fully sedated. A full-thickness excisional wound measuring 2 × 2 cm was then created on the shaved dorsal region using sterile surgical scissors.

Eight Sprague–Dawley rats were randomly assigned to two groups. In the experimental group (n = 4), wounds were topically treated with the prepared S. mukorossi seed hydrosol (SMH 1:2) and covered with porous bandages. The SMH treatment was administered once every 2 days over a 14-day period. In the control group (n = 4), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was applied to the wounds instead of SMH. Following wounding, all rats were housed individually. To monitor the healing progression, digital photographs of the wound sites were taken every 4 days starting from day 2. Wound areas were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and wound closure was expressed as a percentage of the original wound area. After the experiments, the rats were euthanized by CO2 inhalation overdose following the Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition published by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). In brief, CO2 gas was supplied from a commercial high-pressure cylinder. To avoid placing the animals directly into 100% CO2, the gas inflow rate into the euthanasia chamber was precisely adjusted using a flow meter to 20% (cage volume/min). The CO2 flow was maintained for two minutes after the animals ceased breathing, and death was confirmed by physical examination. No additional gases were mixed with CO2 to avoid prolonging the time to death.

For the histological evaluation of wound healing, an additional six rats were used for microscopic observation. Full-thickness skin wounds were created on the dorsal area of the mice as described above. At 6 and 14 days post-injury, mice were euthanized and wounded skin tissue was harvested and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The tissue was embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination. Epidermal regeneration was identified from the histological images obtained by an optical microscope.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed using a free on-line calculator (https://www.statskingdom.com/shapiro-wilk-test-calculator.html) and did not show a significant departure from normality for any data in this study. Between-groups comparison between groups was performed using the one-way ANOVA post hoc with Tukey’s HSD. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chhetri, A. B., Tango, M. S., Budge, S. M., Watts, K. H. & Islam, M. R. Non-edible plant oils as new sources for biodiesel production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9, 169–180 (2008).

Sonawane, S. M. & Sonawane, H. A review of recent and current research studies on the biological and pharmalogical activities of Sapindus mukorossi. Int. J. Interdiscip. Res. Innov. 3, 85–95 (2015).

Anjali, R. S. & Divya, J. Sapindus mukorossi: A review article. Pharma. Innov. 7, 470–472 (2018).

Kuo, Y. H. et al. New dammarane-type saponins from the galls of Sapindus mukorossi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 4722–4727 (2005).

Yin, S. W. et al. Physicochemical and structural characterisation of protein isolate, globulin and albumin from soapnut seeds (Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn.). Food Chem. 128, 420–426 (2011).

Sharma, A., Sati, S. C., Sati, O. P., Sati, M. D. & Kothiyal, S. K. Triterpenoid saponins from the pericarps of Sapindus mukorossi. J. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/613190 (2013).

Upadhyay, A. & Singh, D. K. Pharmacological effects of Sapindus mukorossi. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 54, 273–280 (2012).

Suhagia, B. N., Rathod, I. S. & Sindhu, S. Sapindus mukorossi (Areetha): An overview. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2, 1905–1913 (2011).

Singh, R. & Kumari, N. Comparative determination of phytochemicals and antioxidant activity from leaf and fruit of Sapindus mukorrossi Gaertn.—A valuable medicinal tree. Ind. Crop. Prod. 73, 1–8 (2015).

Zhao, Z., Zhang, A., Song, L., He, C. & He, H. Evaluation of Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn flower water extract on in vitro anti-acne activity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47050316 (2025).

Kumar, P., Vijeth, Fernandes, P. & Raju, K. A Study on performance and emission characteristics of cotton seed methyl ester, Sapindous mukorossi seed oil, and diesel blends on CI engine. Energy Power 5, 10–14 (2015).

Mahar, K. S., Rana, T. S. & Ranade, S. A. Molecular analyses of genetic variability in soap nut (Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 34, 1111–1118 (2011).

Chen, Y. H., Chiang, T. H. & Chen, J. H. Properties of soapnut (Sapindus mukorossi) oil biodiesel and its blends with diesel. Biomass Bioenergy. 52, 15–21 (2013).

Demirbas, A., Bafail, A., Ahmad, W. & Sheikh, M. Biodiesel production from non-edible plant oils. Energ. Explor. Exploit. 34, 290–318 (2016).

Shiu, S. T., Lew, W. Z., Lee, S. Y., Feng, S. W. & Huang, H. M. Effects of Sapindus mukorossi seed oil on proliferation, osteogenetic/odontogenetic differentiation and matrix vesicle secretion of human dental pulp mesenchymal stem cells. Materials 13, 4063. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13184063 (2020).

Kuo, P. J., Lin, Y. H., Huang, Y. X., Lee, S. Y. & Huang, H. M. Effects of Sapindus mukorossi seed oil on bone healing efficiency: An animal study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 6749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25126749 (2024).

Huang, Y. X., Lin, Y. C., Lin, X. K. & Huang, H. M. ω-9 monounsaturated fatty acids in Sapindus mukorossi seed oil enhance calcium deposition expression of Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell. 91, 102595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tice.2024.102595 (2024).

Lin, S. K., Wu, Y. F., Chang, W. J., Feng, S. W. & Huang, H. M. The treating efficiency and microbiota analysis of Sapindus mukorossi seed oil on the ligature-induced periodontitis rat model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158560 (2022).

Chen, C. C. et al. Effects of Sapindus mukorossi seed oil on skin wound healing: In vivo and in vitro testing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102579 (2019).

Rekik, D. M. et al. Evaluation of wound healing properties of grape seed, sesame, and fenugreek oils. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7965689 (2016).

Dakiche, H., Khali, M. & Boutoumi, H. Phytochemical characterization and in vivo anti-inflammatory and wound-healing activities of Argania spinosa (L.) skeels seed oil. Rec. Nat. Prod. 11, 171–184 (2017).

Chang, Z. Y. et al. The elucidation of structure–activity and structure-permeation relationships for the cutaneous delivery of phytosterols to attenuate psoriasiform inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110202 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. β-sitosterol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and lipogenesis disorder in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241914644 (2023).

Chakraborty, M. & Baruah, D. C. Production and characterization of biodiesel obtained from Sapindus mukorossi kernel oil. Energy 60, 159–167 (2013).

Marques, S. R., Peixoto, C. A., Messias, J. B., de Albuquerque, A. R. & da Silva Jr, V. A. The effects of topical application of sunflower-seed oil on open wound healing in lambs. Acta Cir. Bras. 19, 196–209 (2004).

Zhou, Y. et al. Natural polyphenols for prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutrients 8, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8080515 (2016).

Liu, C. et al. Research progress of polyphenols in nanoformulations for antibacterial application. Mater. Today Bio https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100729 (2023).

Manso, T., Lores, M. & de Miguel, T. Antimicrobial activity of polyphenols and natural polyphenolic extracts on clinical isolates. Antibiotics (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11010046 (2021).

Huang, S., Wu, H., Jiang, Z. & Huang, H. Water-based nanosuspensions: Formulation, tribological property, lubrication mechanism, and applications. J. Manuf. Process. 71, 625–644 (2021).

Almeida, H. H. S., Fernandes, I. P., Amaral, J. S., Rodrigues, A. E. & Barreiro, M.-F. Unlocking the potential of hydrosols: Transforming essential oil byproducts into valuable resources. Molecules 29, 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29194660 (2024).

Khan, M. et al. The composition of the essential oil and aqueous distillate of Origanum vulgare L. growing in Saudi Arabia and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 11, 1189–1200 (2018).

Aćimović, M. G. et al. Hydrolates—by-products of essential oil distillation: Chemical composition, biological activity and potential uses. Adv. Technol. 9, 54–70 (2020).

Chemat, F., Vian, M. A. & Cravotto, G. Green extraction of natural products: Concept and principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 8615–8627 (2012).

Nour, A. H., Modather, R. H., Yunus, R. M., Elnour, A. A. M. & Ismail, N. A. Characterization of bioactive compounds in patchouli oil using microwave-assisted and traditional hydrodistillation methods. Ind. Crops. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117901 (2024).

Jakubczyk, K., Tuchowska, A. & Janda-Milczarek, K. Plant hydrolates—antioxidant properties, chemical composition and potential applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112033 (2021).

Hassiotis, C. N. Chemical compounds and essential oil release through decomposition process from Lavandula stoechas in Mediterranean region. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 38, 493–501 (2010).

D’Amato, S., Serio, A., López, C. C. & Paparella, A. Hydrosols: Biological activity and potential as antimicrobials for food applications. Food Control 86, 126–137 (2018).

Bairamis, A., Sotiropoulou, N.-S.D., Tsadila, C., Tarantilis, P. & Mossialos, D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils and hydrosols from oregano, sage and pennyroyal against oral pathogens. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14083238 (2024).

Allan, D., Radzinski, S. C., Tapsak, M. A. & Liggat, J. J. The thermal degradation behavior of a series of siloxane copolymers - a study by thermal volatilisation analysis. SILICON 8, 553–562 (2016).

Ahmeda, A., Zangeneh, M. M. & Zangeneh, A. Green formulation and chemical characterization of Lens culinaris seed aqueous extract conjugated gold nanoparticles for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in comparison to mitoxantrone in a leukemic mouse model. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 34, e5369. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5369 (2020).

Mohammadi, G., Zangeneh, M. M., Zangeneh, A. & Haghighi, Z. M. S. Chemical characterization and anti-breast cancer effects of silver nanoparticles using Phoenix dactylifera seed ethanolic extract on 7,12-Dimethylbenz[a] anthracene-induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in Sprague Dawley male rats. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 34, e5136. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5136 (2020).

Abbasia, N., Ghaneialvar, H., Moradi, R., Zangeneh, M. M. & Zangeneh, A. Formulation and characterization of a novel cutaneous wound healing ointment by silver nanoparticles containing Citrus lemon leaf: A chemobiological study. Arab. J. Chem. 14, 202107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103246 (2021).

Zangeneh, A., Zangeneh, M. M. & Moradi, R. Ethnomedicinal plant-extract-assisted green synthesis of iron nanoparticles using Allium saralicum extract, and their antioxidant, cytotoxicity, antibacterial, antifungal and cutaneous wound-healing activities. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 34, e5247. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5247 (2020).

Rhetso, T., Shubharani, R., Roopa, M. S. & Sivaram, V. Chemical constituents, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of Allium chinense G. Don. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 6, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-020-00100-7 (2020).

Begum, I. F., Mohankumar, R., Jeevan, M. & Ramani, K. GC–MS analysis of bio-active molecules derived from Paracoccus pantotrophus FMR19 and the antimicrobial activity against bacterial pathogens and MDROs. Indian J. Microbiol. 56, 426–432 (2016).

Girija, S., Duraipandiyan, V., Kuppusamy, P. S., Gajendran, H. & Rajagopal, R. Chromatographic characterization and GC-MS evaluation of the bioactive constituents with antimicrobial potential from the pigmented ink of Loligo duvauceli. Int. Sch. Res. Notices https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/820745 (2014).

Al-Youssef, H. M. & Hassan, W. H. B. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Parkinsonia aculeata and chemical composition of their essential oils. Merit Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 3, 147–157 (2015).

Boussaada, O. et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of volatile components from capitula and aerial parts of Rhaponticum acaule DC growing wild in Tunisia. Microbiol. Res. 163, 87–95 (2008).

Yogeswari, S., Ramalakshmi, S., Neelavathy, R. & Muthumary, J. Identification and comparative studies of different volatile fractions from Monochaetia kansensis by GCMS. Glob. J. Pharmacol. 6, 65–71 (2012).

Isman, M. B., Proksch, P. & Yan, J. Y. Insecticidal chromenes from the Asteraceae: Structure–activity relations. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 43, 87–93 (1987).

Fridman-Cohen, S. & Pener, M. P. Precocenes induce effect of juvenile hormone excess in Locusta migratoria. Nature 286, 711–713 (1980).

Mao, L., Henderson, G. & Dong, S. Studies of precocene I, precocene II and biogenic amines on formosan subterranean termite (lsoptera: Rhinotermitidae) presoldier/soldier formation. J. Entomol. Sci. 45, 27–34 (2010).

Amiri, A., Bandani, A. R. & Ravan, S. Effect of an anti-juvenile hormone agent (Precocene I) on Sunn pest, Eurygaster integriceps (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae) development and reproduction. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 9, 5859–5868 (2010).

Chandni, et al. Phytochemical characterization and biomedical potential of Iris kashmiriana flower extracts: A promising source of natural antioxidants and cytotoxic agents. Sci. Rep. 14, 24785. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58362-7 (2024).

Doshi, G. M. et al. Structural elucidation of chemical constituents from Benincasa hispida seeds and Carissa congesta roots by gas chromatography: Mass spectroscopy. Pharmacognosy Res. 7, 282–293 (2015).

Rouvier, F. et al. Identification of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol as an antimicrobial agent against Cutibacterium acnes bacteria from Rwandan Propolis. Antibiotics 13, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13111080 (2024).

Saha, P., Sharma, D., Dash, S., Dey, K. S. & Sil, S. K. Identification of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP) as the major contributor of anti-colon cancer activity of active chromatographic fraction of Parkia javanica (Lamk.) Merr. bark extract. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 16, 275–288 (2023).

Varsha, K. K. et al. 2,4-di-tert-butyl phenol as the antifungal, antioxidant bioactive purified from a newly isolated Lactococcus Sp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 211, 44–50 (2015).

Zhao, F., Wang, P., Lucardi, R. D., Su, Z. & Li, S. Natural sources and bioactivities of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12010035 (2020).

Nair, R. V. R., Jayasree, D. V., Biju, P. G. & Baby, S. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of erythrodiol-3-acetate and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol isolated from Humboldtia unijuga. Nat. Prod. Res. 34, 2319–2322 (2020).

Kersch-Becker, M. F., Kessler, A. & Thaler, J. S. Plant defences limit herbivore population growth by changing predator-prey interactions. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20171120. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1120 (2017).

Miklasińska-Majdanik, M., Kępa, M., Wojtyczka, R. D., Idzik, D. & Wąsik, T. J. Phenolic compounds diminish antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102321 (2018).

de Moura Sperotto, N. D. et al. Wound healing and anti-inflammatory activities induced by a Plantago australis hydroethanolic extract standardized in verbascoside. J. Ethnopharmacol. 225, 178–188 (2018).

Du, M. et al. Isolation of total saponins from Sapindus mukorossi Gaerth. Open J. For. 4, 24–27 (2014).

Wan, Y. et al. Extraction of rose hydrosol from Yunnan Dark Red Rose by steam distillation: Optimization, antioxidant activity, and flavor assessment. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 1496327. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1496327 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by En Chu Kong Hospital, grant number ECKH_W11308.

Funding

This research was funded by En Chu Kong Hospital, New Taipei City, Taipei, Taiwan (grant number ECKH_W11308).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.H. and C.K.L. designed the experiments. H.Y.L., Y.C.C.L., and K.H.F. performed the experiments. R.P.V., N.P., and Y.U. analyzed the data. H.M.H. and H.Y.L. wrote the manuscript. H.M.H. and C.K.L. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, H., Lu, YC.C., Fan, KH. et al. Investigating the biological activities of Sapindus mukorossi seed hydrosol and its potential as a skincare ingredient. Sci Rep 15, 42801 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27030-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27030-9