Abstract

Urban air pollution poses a considerable risk to both public health and environmental sustainability, highlighting the importance of precise, low-latency forecasting systems that can be integrated into real-world infrastructures. This research presents the Urban Air Quality Forecasting with Grid-Embedded Recurrent MLP Model (AiM), a hybrid model that merges a recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) with a Grid-Embedded framework that takes spatial factors into account, aiming to improve air quality predictions across space and time. It employs a grid-based partitioning strategy for urban monitoring areas, allowing it to effectively capture localized patterns in pollutant dispersion, while the R-MLP aspect addresses the complex temporal dependencies found in multi-pollutant and meteorological time series data. A customized feature engineering pipeline is designed to incorporate pollutant interactions, meteorological variability, and grid adjacency relationships, facilitating the robust learning of cross-regional correlations. Experiments conducted on multi-season, multi-station datasets reveal that AiM achieves superior forecasting accuracy compared to conventional LSTM, GRU, and CNN-RNN hybrids, reducing RMSE by as much as 12.4% and inference latency by 35% on edge devices. Furthermore, the architecture demonstrates high scalability, accommodating dynamic grid reconfiguration and integration with low-power IoT nodes, making it well-suited for real-time deployment in smart city air quality management systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution stands as one of the most urgent environmental and public health challenges facing modern urban centers1. This issue is primarily driven by rapid industrialization, increasing vehicular traffic2, and changing climatic conditions3,4. Fine particulate matter (PM\(_{2.5}\) and PM\(_{10}\)), nitrogen dioxide (NO\(_2\)), carbon monoxide (CO), and other pollutants have been directly associated with respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular diseases, and diminished life expectancy5,6. The intricate dynamics of pollutant dispersion, influenced by meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and atmospheric pressure, require sophisticated forecasting models that can effectively capture non-linear spatiotemporal patterns.

Traditional statistical forecasting techniques7,8,9 are often computationally efficient but typically struggle to accurately capture the complex dependencies inherent in urban air quality data. In contrast, deep learning (DL) architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks10, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)11, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)12, and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)13,14,15 have shown superior performance. However, these models frequently face challenges related to high computational complexity, limited edge-deployability, and inadequate modeling of fine-grained spatial heterogeneity, which is crucial for effective urban interventions16,17,18,19,20.

To address these limitations, we introduce AiM, an innovative hybrid framework that combines a grid-based spatial embedding mechanism with a recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) architecture. The grid embedding divides the urban landscape into spatial cells, allowing for the effective capture of localized pollutant patterns and cross-regional dependencies through adjacency-aware feature integration. Meanwhile, the recurrent MLP efficiently models temporal dynamics and maintains a lightweight structure, making it suitable for deployment on low-power IoT devices.

Research gaps

-

Limited Utilization of Spatial Heterogeneity: Many existing approaches21 primarily frame air quality prediction as a temporal issue, often neglecting the spatial variability present across different urban zones.

-

High Computational Complexity: While state-of-the-art deep learning architectures (such as LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and Transformers) achieve impressive accuracy, they demand substantial computational resources, which restricts their practical deployment in real-world IoT scenarios22.

-

Insufficient Spatiotemporal Feature Fusion: Current models frequently struggle to integrate pollutant interactions, meteorological conditions, and spatial relationships into a unified representation, thereby hampering their ability to effectively capture complex dispersion dynamics23.

-

Lack of Grid-based Environmental Modeling: There is a scarcity of methods employing structured spatial partitioning (grid embedding) to illustrate urban pollutant dynamics, which results in underutilizing the effects of neighboring areas.

-

Challenges in Generalization Across Heterogeneous Conditions: Models trained on datasets from a single location10,24 often exhibit a lack of robustness when applied to different cities, seasons, and pollution scenarios.

Key challenges

-

Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency: Striving for exceptional predictive performance while minimizing memory consumption and inference latency, ideally suited for edge deployment.

-

Dynamic Spatial Correlations: Capturing time-varying dependencies among grid cells that are influenced by factors such as wind, traffic, and meteorological conditions.

-

Multi-Scale Temporal Modeling: Effectively learning both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends while avoiding issues related to noise and seasonal biases.

-

Data Sparsity and Irregularity: Addressing the challenges of missing sensor readings, irregular sampling intervals, and noisy measurements prevalent in real-world IoT networks.

-

Scalability and Adaptability: Ensuring the model can scale to accommodate larger grids and additional sensors without the need for complete retraining.

Addressing these gaps is essential for the development of a forecasting framework that is both accurate and computationally efficient. The proposed AiM model directly confronts these challenges by incorporating spatial grids within a recurrent MLP structure, thereby enhancing the learning of spatiotemporal features while maintaining a lightweight design suitable for edge deployment.

Motivation

Urban air pollution remains a critical environmental and public health issue, with PM\(_{2.5}\), PM\(_{10}\), NO\(_2\), and CO identified as key pollutants associated with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, as well as decreased life expectancy5,6. The rapid pace of urbanization, coupled with increasing vehicular traffic and industrial activities, has heightened the demand for accurate, timely, and location-specific air quality forecasts to facilitate proactive mitigation strategies.

Although deep learning techniques such as LSTM10, GRU11, and hybrid CNN-RNN models25 have demonstrated potential, they encounter several limitations. Specifically, they often overlook fine-grained spatial heterogeneity, impose substantial computational and memory demands that are not well-suited for IoT devices, and fail to account for multi-source influences, including pollutant interactions, meteorological factors, and spatial adjacency.

Additionally, the dispersion of urban pollutants is inherently spatiotemporal, influenced by the interplay among emission sources, meteorological conditions, and urban topography. A practical forecasting framework must therefore capture both spatial patterns to comprehend localized propagation and temporal dependencies to predict changes over time amidst varying environmental conditions.

The proposed AiM framework comprehensively addresses these challenges by integrating grid-based spatial embeddings with recurrent temporal modeling to enhance spatiotemporal feature learning. It ensures low-latency and lightweight inference suitable for edge devices while effectively scaling across diverse city layouts, sensor densities, and pollution profiles without the need for retraining.

By bridging the gap between high-accuracy forecasting and practical deployment on the edge, AiM provides urban planners and policymakers with real-time, interpretable insights into air quality, thereby supporting proactive and data-driven interventions.

The principal contributions of this work are as follows:

-

1.

We introduce a grid-embedded recurrent MLP framework tailored for urban air quality forecasting, which effectively combines spatial partitioning with temporal modeling to enhance predictive performance.

-

2.

We develop a feature engineering pipeline that integrates pollutant interactions, meteorological variables, and spatial adjacency relations, enabling the model to capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies.

-

3.

We conduct extensive experiments on multi-station, multi-season datasets, demonstrating that AiM outperforms traditional LSTM, GRU, and CNN-RNN baselines in terms of both accuracy and inference latency.

-

4.

We evaluate the feasibility of deploying AiM on edge computing devices, highlighting a reduction in model size and computation time while preserving prediction accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section Literature Survey provides a review of relevant literature on air quality forecasting and spatiotemporal deep learning techniques. Section System Formulation discusses the architecture of AiM and its essential components. In Section Problem Formulation, we define the problem formulation. Section Methodologies for Developing the AiM Model outlines the methodologies employed in the design of the proposed AiM framework. Section Proposed AiM Framework details the AiM framework itself. Section Analysis of Experimental Results describes the experimental setup and presents the results. Section Applications of the AiM Model examines the implications and potential extensions of AiM. Lastly, Section Conclusion & Future Work concludes the paper and suggests directions for future work.

Literature survey

Accurate forecasting of urban air quality requires models that account for both complex temporal dynamics and spatial variability.

Classical and machine learning approaches

Early air quality forecasting efforts primarily relied on statistical models, such as ARIMA26 and SARIMAX27, alongside classical machine learning techniques, including Support Vector Regression28, Random Forest29, and XGBoost30. While these methods26,27,28,29,30 are typically lightweight and interpretable, they often struggle to capture the intricate, non-linear spatiotemporal interactions that characterize urban pollutant dispersion, especially when influenced by various meteorological and anthropogenic factors31. To bolster robustness in operational systems, hybrid approaches have been developed that integrate these diverse methodologies.

Deep temporal approaches

Recurrent architectures, such as LSTM10 and GRU11, have gained widespread use for predicting pollutant time-series due to their ability to effectively learn temporal dependencies. To better capture local patterns and short-term dynamics, researchers have begun integrating convolutional layers with recurrent layers, which has led to enhanced accuracy in various urban and regional case studies. For example, CNN-LSTM10 and its variants32,33,34 have been successfully applied to city-scale PM\(_{2.5}\) forecasting tasks, demonstrating significant improvements in accuracy over traditional RNNs.

Spatiotemporal graph and grid-based models

The presence of spatial heterogeneity and inter-station dependencies has prompted the development of spatially-aware models35,36,37. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and spatiotemporal graph convolutional networks (ST-GCN/T-GCN) construct station graphs, wherein edge weights are influenced by factors such as distance, wind, and learned correlations38,39. These models38,39 effectively capture both spatial and temporal relationships, often achieving superior performance when compared to non-spatial baselines in predicting multi-site PM\(_{2.5}\) levels. Furthermore, recent studies40,41 have introduced dynamic geographical graphs that modify their adjacency based on prevailing meteorological conditions and evolving relationships over time.

An alternative to explicit graph modeling is the use of grid-based or patch-based spatial encoding. In this method, urban areas are segmented into regular cells as grid embedding inputs that are subsequently processed using convolutional or hybrid networks to capture neighborhood effects42. Grid-embedding techniques are especially beneficial in contexts with high station density or when incorporating remote sensing data and gridded auxiliary fields.

MLP-style and mixer architectures for time series

Recently, the research community has shifted its focus towards standard MLPs and MLP-mixer-style architectures for time series forecasting43. Innovations such as TSMixer, PatchMLP, and frequency-domain MLP variants have demonstrated that well-designed MLPs through adequate mixing across both time and feature dimensions or by utilizing frequency-domain transformations can achieve competitive forecasting performance while incurring lower inference costs compared to more complex transformer or recurrent models44,45,46. These advances highlight the potential for exploring lightweight MLP-based recurrent hybrids for multivariate forecasting at the edge.

Edge deployment, model compression, and TinyML

In the context of deploying operational smart cities, minimizing computational footprint and energy consumption is essential. Research on TinyML and model compression techniques–such as post-training quantization, pruning, and TensorFlow Lite–has shown that large deep learning models can be significantly reduced in size with only a modest trade-off in accuracy47. This facilitates real-time inference on microcontrollers and single-board computers. Evaluations often reveal considerable reductions in both model size and inference latency, underscoring the viability of edge-based air-quality forecasting when combined with efficient architectures and compression strategies48.

Consequently, AiM capitalizes on these insights by (i) embedding spatial information into a regular grid format that preserves the neighborhood structure, (ii) incorporating a recurrent MLP (R-MLP) to effectively capture temporal dynamics while minimizing computational costs, and (iii) establishing a pipeline specifically designed for model compression and on-device inference. This approach seeks to combine the accuracy advantages of spatiotemporal models with the efficiency required for IoT edge deployment.

System formulation

To design the AiM framework, we start by embedding the urban environment within a structured Spatial Grid Representation (SGR), where each grid cell represents a localized monitoring zone, complete with associated pollutant and meteorological data, as illustrated in Figure 1.

This embedding is incorporated into the Recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) architecture, allowing us to effectively model both spatial adjacency and temporal dependencies. The quantitative advantages of this integration are articulated through the following equations:

Here, Equation (1) quantifies forecasting accuracy improvement (AccGain), Equation (2) measures latency reduction (LatRed) for real-time deployment, and Equation (3) captures the improvement in spatial correlation modeling (SpImp) between predicted and observed pollutant dispersion patterns.

Advantages of grid-embedded recurrent MLP

The proposed R-MLP featuring spatial grid embedding presents several notable technical advantages:

-

1.

Spatial-Temporal Fusion: The grid embedding allows the model to integrate adjacency-aware spatial features with sequential temporal inputs, effectively capturing pollutant transport across different regions.

-

2.

Computational Efficiency: In contrast to deep recurrent or transformer-based architectures, the R-MLP employs a shallow yet expressive design, which minimizes memory usage and reduces inference time, making it suitable for IoT and edge deployments.

-

3.

Adaptability: The architecture offers dynamic reconfiguration of the grid, accommodating sensor additions or layout changes without the need for complete retraining.

-

4.

Scalability: The model is capable of scaling from small urban districts to extensive metropolitan grids by adjusting the resolution of the embedding as needed.

Three-phase AiM system architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the modular design of AiM, which consists of three integrated phases. Phase 1 involves the Spatial Grid Embedding of urban monitoring zones, enriched with pollutant and meteorological attributes. Phase 2 focuses on temporal modeling through the R-MLP, where recurrent connections effectively capture multi-scale dependencies over time. Phase 3 implements multi-step forecasting using recursive inference, allowing the output at time t to serve as input for predicting the AQI at \(t+1\) across an H-hour horizon. Together, these phases empower AiM to effectively learn both spatial and temporal dynamics for accurate urban air quality predictions.

Recursive multi-step prediction formulation

The per-hour forecasting mechanism is formulated as:

Here, \(H_t\) is the hidden state at time t, \(G_t\) is the spatial grid embedding vector, \(MF_t\) represents meteorological factors, and \(\hat{Y}_t\) is the predicted pollutant concentration. The recursive sequence \(\textbf{Y}_{1:H}\) represents the full H-hour horizon prediction.

Grid-embedding formulation

This formulation ensures that AiM effectively captures spatial dependencies through grid embeddings, as illustrated in Fig. 2. It also models temporal patterns with the R-MLP recurrent structure, enabling accurate, efficient, and scalable urban air quality forecasting, as detailed in Algorithm 1.

Problem formulation

The objective of AiM is to accurately forecast the future air quality index (AQI) values over an H-hour horizon for an urban region, leveraging both spatial and temporal dependencies in sensor and meteorological data. Let,

-

\(\mathcal {S}_t = \{ s^1_t, s^2_t, \dots , s^N_t \}\) denote pollutant measurements from N heterogeneous sensors at time step t, where each \(s^i_t \in \mathbb {R}^{P}\) contains P pollutant features (e.g., PM\(_{2.5}\), NO\(_2\), CO).

-

\(\mathcal {M}_t \in \mathbb {R}^{Q}\) represent meteorological factors (e.g., temperature, humidity, wind speed, wind direction) at time step t.

-

\(\mathcal {G}\) denote the spatial grid configuration covering the urban region, divided into C grid cells.

Spatial grid embedding

Sensor observations are mapped to their corresponding grid cells according to their spatial coordinates:

where \(\mathcal {F}_{\textrm{map}}(\cdot )\) aggregates multiple sensors in the same cell, e.g.,

with \(\mathcal {V}_c\) being the set of sensors in cell c.

Spatial adjacency is encoded via an adjacency matrix \(\textbf{A} \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times C}\):

The grid embedding at time t is formed by concatenating pollutant aggregates, meteorological variables, and adjacency-based features:

Here, \(d_g\) is the embedding dimension.

Recurrent MLP temporal modeling

The temporal dynamics of urban air pollutants are captured via a Recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP), which maintains a hidden state \(H_t \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\) across time steps:

Here, \(G_t \in \mathbb {R}^{d_g}\) denotes the grid-embedded spatial input at time t, while \(W_g \in \mathbb {R}^{d_m \times d_g}\) serves to project this input into an intermediate latent space of dimension \(d_m\). The function \(\phi (\cdot )\) applies a non-linear activation (such as ReLU) element-wise. The weights \(W_h\) and \(U_h\) are learnable parameters corresponding to input and recurrent connections, respectively, and \(\sigma (\cdot )\) represents a gating function (such as \(\tanh\)) that modulates the update of the hidden state.

The recurrent connection \(U_h H_{t-1}\) enables the R-MLP to retain a memory of prior time steps, effectively capturing both short-term fluctuations and long-term temporal dependencies in pollutant concentrations. The residual-style MLP blocks within the R-MLP facilitate stable gradient flow, further enhancing the model’s capability to integrate historical patterns over extended time horizons.

To explicitly model interactions among multiple pollutants, the input \(G_t\) can encompass concatenated features of PM\(_{2.5}\), PM\(_{10}\), NO\(_2\), CO, and other relevant pollutants, in addition to meteorological factors. This allows the R-MLP to learn cross-pollutant dependencies, as different pollutants may evolve across varying temporal scales, thereby enriching the predictive representation.

Table 1 summarizes how the R-MLP captures these relationships.

Multi-step forecasting

The output layer maps the hidden state to AQI predictions:

For an H-hour prediction horizon, the recursive forecasting is:

where:

to enable recursive multi-step prediction.

While the autoregressive approach allows for sequential predictions, it also introduces a compounding error effect, where inaccuracies from earlier steps impact subsequent forecasts, especially for longer time horizons.

To systematically evaluate this behavior, we examine the growth of the root mean squared error (RMSE) across various prediction step lengths (\(k = 1, 3, 6, 12, 24\) hours) to quantify the temporal stability of the AiM model. This analysis offers empirical evidence on how cumulative errors develop over time, providing valuable insights into the model’s robustness for longer forecasting horizons. Figure 3 illustrates the trends in RMSE as the forecast periods increase, showing that while short-term predictions maintain a high degree of stability, there is a gradual accumulation of errors beyond 12-hour intervals–an expected behaviour for recursive inference models.

Optimization Objective

The model is trained to minimize the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between predicted and true AQI values:

Optionally, a regularization term can be included:

where \(\Theta\) is the set of model parameters and \(\lambda\) is a regularization coefficient.

The AiM is to learn parameters \(\Theta = \{ W_g, W_h, U_h, W_o, b_g, b_h, b_o \}\) that minimize \(\mathcal {L}\), thereby producing accurate, efficient, and scalable AQI forecasts leveraging both spatial grid embeddings and recurrent MLP temporal modeling.

Methodologies for developing the AiM model

Recurrent multi-layer perceptron (R-MLP)

The Recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) is a lightweight recurrent architecture designed to capture temporal dependencies while keeping inference and memory costs low for edge deployment, as shown in Fig. 4. Unlike conventional recurrent architectures such as LSTM or GRU, the R-MLP eliminates complex gating and cell-state transitions, replacing them with a residual feedback mechanism that ensures stable information flow while significantly reducing computational burden.

In AiM, the R-MLP ingests the spatial grid embedding \(G_t\) together with meteorological factors \(MF_t\) and produces a hidden state \(H_t\) used to predict pollutant concentrations \(\hat{y}_t\). This formulation enables efficient spatiotemporal fusion without incurring the high recurrent overhead of memory-based networks.

The R-MLP architecture comprises several key components. It begins with an input projection layer that transforms the grid-embedded features into a compact representation. This is followed by one or more residual MLP blocks equipped with recurrent connections to capture temporal dependencies. Finally, a lightweight output head maps the recurrent hidden state to the target pollutant predictions, enabling efficient and accurate forecasting.

Mathematical formulation of R-MLP

Let \(G_t\in \mathbb {R}^{d_g}\) be the grid embedding at time t, and \(m_t\in \mathbb {R}^{d_m}\) be meteorological factors. The R-MLP update for one time step is:

Here, \(W_g\in \mathbb {R}^{d_x\times (d_g+d_m)}\) and \(b_g\) are input projection parameters; \(\phi _g(\cdot )\) is an input activation (e.g., ReLU). For layer \(\ell\), \(W^{(\ell )}\in \mathbb {R}^{d_x\times d_x}\), \(b^{(\ell )}\in \mathbb {R}^{d_x}\), \(\phi (\cdot )\) is a nonlinearity (ReLU/tanh), and \(\alpha ^{(\ell )}\) is a (learnable or fixed) residual scaling. L is the number of MLP blocks per time step.

To inject recurrence, the hidden-state mixing is applied after the MLP blocks:

Here, \(U_h\in \mathbb {R}^{d_h\times d_h}\), \(V_u\in \mathbb {R}^{d_h\times d_x}\), \(b_h\in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\), and \(\psi (\cdot )\) is typically \(\tanh\) or ReLU. This recurrent update replaces memory-cell dynamics with a compact feedback loop, making it less prone to vanishing gradients compared to deep recurrent stacks while maintaining effective temporal smoothing. Optionally, a simple gating can be added:

with \(\tilde{H}_t\) as in Equation (21). Although simpler than LSTM gates, this optional gate helps regulate temporal drift over long horizons. In the context of the spatial mapping above, future analysis of gradient propagation across Equations (21) can further establish its stability in long-term forecasting.

The output prediction for pollutant(s) is:

Multi-step recursive forecasting

For multi-hour horizon H, we employ recursive (autoregressive) forecasting:

This iterative approach enables adaptive forecasting across multiple temporal resolutions, offering flexibility to evaluate performance across both short- and long-range dependencies.

Training objective

We optimize a weighted multi-horizon MSE (optionally combined with MAE and regularization):

Here, \(\Theta\) collects all trainable parameters, \(w_k\) are horizon weights (e.g., decaying), and \(\lambda\) is an \(L_2\) regularization factor. An ablation-based evaluation over multiple prediction horizons can further validate the robustness of this loss function in maintaining stable convergence across long-term sequences.

Complexity and edge considerations

Per time-step complexity is dominated by matrix multiplications in the MLP blocks and the recurrence:

To maintain Tiny-ML compatibility, the model adopts compact design choices: the input and hidden dimensions (\(d_x, d_h\)) are kept small, typically ranging from 32 to 128; the number of residual MLP blocks (L) is limited to 1–3 to reduce complexity; and post-training quantization (8-bit) with integer kernels via TensorFlow Lite is employed to enable efficient deployment on edge devices.

Thus, R-MLP achieves a trade-off between temporal modeling depth and deployment efficiency, making it ideal for real-time edge-based environmental inference.

Training of the designed R-MLP is described in Algorithm 2.

Table 2 presents the optimized hyperparameter configuration for the R-MLP component within the AiM framework, along with explanations of their selection based on validation experiments and edge deployment considerations.

Spatial grid embedding architecture

The Spatial Grid Embedding module in the AiM framework captures the spatial dependencies in urban air pollutant concentrations by discretizing the geographic region into structured grids and encoding sensor observations into a compact representation suitable for temporal modeling, as illustrated in Fig. 5. In contrast to raw coordinate-based encoding, this grid-based approach provides a structured spatial abstraction that enhances locality awareness and enables efficient learning of pollutant diffusion dynamics across neighboring urban zones.

Spatial Grid Embedding architecture in the AiM framework. The module maps heterogeneous sensor data into a structured spatial grid, aggregates pollutant and meteorological features, augments with adjacency-based spatial correlations, and projects to a low-dimensional embedding for temporal modeling via R-MLP.

Let \(\mathcal {S}_t = \{ s_{1,t}, s_{2,t}, \dots , s_{N,t} \}\) represent the set of pollutant and meteorological readings at time step t, collected from N heterogeneous sensors distributed across the city. The spatial domain \(\Omega\) is partitioned into a fixed grid \(\mathcal {G} \in \mathbb {R}^{R \times C}\), where R and C are the number of rows and columns, respectively. Each sensor \(s_{i,t}\) is mapped to its corresponding grid cell \(\mathcal {G}(r_i, c_i)\) according to its geographic coordinates \((lat_i, lon_i)\).

The choice of grid resolution (\(R \times C\)) plays a pivotal role in determining model performance. A finer grid increases spatial granularity and improves the ability to capture micro-level pollutant variations, but at the cost of higher computational complexity and potential data sparsity in low-density regions. Conversely, a coarser grid reduces computational load and mitigates missing-data issues but may oversmooth local variations. Therefore, grid size selection inherently affects the model’s trade-off between resolution, interpretability, and efficiency.

The spatial aggregation for each grid cell at time t is computed as:

Here, \(\textbf{p}_s(t)\) represents the vector of Air Pollutant Concentrations (APCs), while \(\textbf{m}_s(t)\) signifies the Meteorological Factors (MFs). The symbol \(\Vert\) denotes the concatenation operator, and \(\mathcal {S}_{r,c,t}\) refers to the set of sensors located in cell (r, c) at time t.

To capture spatial correlations between neighboring cells, we implement an adjacency-based feature augmentation. The resulting augmented grid embedding, denoted as \(\tilde{\mathcal {G}}_t\), is derived as follows:

Here, \(\textbf{A}\) represents the adjacency matrix that captures the connectivity of 4 or 8-neighbors between grid cells, while \(\lambda\) serves as a smoothing parameter to regulate spatial influence. By adjusting \(\lambda\), the model can balance maintaining the local identity of grid cells with disseminating spatial information across interconnected regions, thereby reducing the risk of overfitting to isolated grid cells.

Ultimately, the 2D grid representation is transformed into a sequence and projected into a low-dimensional embedding vector:

Here, \(\phi\) represents a non-linear activation function (such as ReLU or GELU), while \(\text {vec}(\cdot )\) denotes vectorization. The parameters \(W_{\text {emb}}\) and \(b_{\text {emb}}\) are learnable components. This projection not only compresses high-dimensional spatial features into a dense embedding but also enables comparison across different grid resolutions by preserving consistent latent dimensions.

The resulting spatial embedding, denoted as \(G_t\), serves as the input for the R-MLP module. This integration enables the AiM framework to simultaneously capture spatial and temporal dependencies, thereby improving the accuracy of urban air quality forecasting.

Proposed AiM framework

The AiM framework outlines our proposed method for efficient and scalable forecasting of urban air quality, as illustrated in Fig. 6. It utilizes a Grid-Embedded Recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) architecture to effectively combine spatial dependencies from grid embeddings with temporal recurrence. This integration enables accurate multi-step predictions well-suited for real-time applications in smart cities.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the proposed methodology encompasses a structured three-stage pipeline. It commences with the Spatial Grid Embedding of Air Pollutant Concentrations (APCs) and Meteorological Factors (MFs) to capture localized environmental data. Subsequently, temporal dependencies are modeled using a recurrent Multi-Layer Perceptron (R-MLP) that incorporates residual connections to facilitate efficient gradient flow. Finally, the framework performs multi-horizon forecasting of pollutant concentrations, enabling precise short- and medium-term predictions across the urban grid.

Spatial grid embedding

Given a set of sensor observations \(\mathcal {S}_t = \{ s_{1,t}, s_{2,t}, \dots , s_{N,t} \}\), the geographic area \(\Omega\) is divided into \(R \times C\) grid cells represented by \(\mathcal {G} \in \mathbb {R}^{R\times C}\). Each sensor reading \(s_{i,t}\) is assigned to a grid cell \((r_i, c_i)\) based on its GPS coordinates.

The aggregated feature vector for the cell \((r,c)\) at time \(t\) is detailed in Equation (28). To enhance this, adjacency-based augmentation is employed, which takes into account the influences of neighboring cells as described in Equation (29). Ultimately, the 2D grid is vectorized and projected using Equation (30).

Recurrent multi-layer perceptron (R-MLP) temporal modeling

The R-MLP integrates the grid embedding \(G_t\) with the previous hidden state \(H_{t-1}\):

where g is an optional gating vector, \(\phi _g\) and \(\psi\) are activations, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication.

Predictions are obtained as:

Algorithm 3 depicts the single-step R-MLP forward pass procedure.

Algorithm 4 defines the end-to-end AiM forecasting.

Figure 7 depicts the flow of the proposed AiM framework.

Analysis of experimental results

This section details the dataset, preprocessing steps, model configurations, baselines, evaluation protocol, metrics, and hardware used to validate the proposed AiM model.

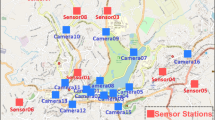

Datasets

We evaluated AiM on urban air-quality datasets collected from large-scale sensor deployments. The primary dataset is sourced from the official Kaggle repository49,50 and contains multiple data streams (APCs, MFs, events) for the period 2015–2020. For this study we extract:

-

Air Pollutant Concentrations (APCs): PM\(_{2.5}\), PM\(_{10}\), NO\(_2\), CO (hourly and daily aggregates).

-

Meteorological Factors (MFs): temperature, humidity, wind speed, wind direction, pressure.

The preparation of the dataset for the AiM model is described in Algorithm 5.

Preprocessing

The raw data are preprocessed with the following pipeline:

-

1.

Time alignment & resampling: all streams are aligned to an hourly grid using forward/backward fill for short gaps. When inconsistent sampling frequencies exist between APC and MF sensors, adaptive resampling ensures uniform temporal granularity without distorting diurnal variation patterns.

-

2.

Outlier handling: sensor outliers are clipped at the 1st and 99th percentiles or replaced via local median filter.

-

3.

Missing values: short gaps (\(\le\) 3 timesteps) are interpolated; longer gaps are masked and imputed using a small MLP imputer trained on neighboring cells. For sensors with persistently high missing ratios, spatial–correlation–based reconstruction is applied using adjacency-weighted estimates from nearby sensors within the same subgrid.

-

4.

Spatial mapping: sensors are mapped to grid cells (Section on Spatial Grid Embedding) and aggregated per cell as \(g_{r,c,t}\).

-

5.

Normalization: features are scaled using51 on the training partition; the same scalers are applied to validation and test splits.

Train/validation/test split

Temporal splits are used to avoid information leakage:

-

Training set: Years 2015–2018

-

Validation set: Year 2019

-

Test set: Year 2020

Where required, a rolling evaluation (walk-forward) protocol is also used to measure model stability across seasons. Additionally, all temporal splits are synchronized post-resampling to guarantee consistent data availability across pollutant and meteorological channels, reducing bias in cross-year evaluations.

Baselines

We compare AiM against the following baselines:

-

Persistence (naïve): last-observed value as forecast.

-

Machine learning: Support Vector Regression28, Random Forest29, and XGBoost30

-

Deep learning: LSTM52, GRU53, CNN-LSTM10, BLSTM54, and Federated Learning based BGRU (FL-BGRU)11.

-

TinyML baseline: quantized GRU deployed via TFLite for edge latency comparison (Edge AI)55.

Hyperparameters for baselines are tuned on the validation set using randomized search.

Evaluation metrics

We evaluate forecasting accuracy and robustness using standard metrics:

-

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2} \end{aligned}$$(35) -

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MAE} = \frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N} |y_i - \hat{y}_i| \end{aligned}$$(36) -

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MAPE} = \frac{100\%}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N} \left| \frac{y_i - \hat{y}_i}{y_i}\right| \end{aligned}$$(37) -

Coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)):

$$\begin{aligned} R^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum _i (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\sum _i (y_i - \bar{y})^2} \end{aligned}$$(38)

We report metrics for multiple horizons (\(H = 1, 3, 6, 12, 24\) hours) and average over spatial cells and temporal windows (daily/seasonal).

Ablation study and grid resolution analysis

To quantify the contribution of each architectural component and understand the efficiency–accuracy trade-offs in the AiM model, we conduct a series of ablation experiments that systematically disable or modify specific design choices.

-

No adjacency augmentation: set \(\lambda = 0\) in the spatial embedding to disable inter-cell influence.

-

No residual connections: remove skip updates in MLP blocks (\(\alpha ^{(\ell )} = 0\)), reducing model depth adaptivity.

-

No gating: replace the gated recurrent update with a simple additive mechanism, \(H_t \leftarrow \tilde{H}_t\).

-

Grid resolution sensitivity: evaluate multiple spatial grid sizes (\(R \times C\)) to assess accuracy–efficiency trade-offs.

Beyond architectural isolation, we empirically evaluate how spatial resolution influences computational cost, predictive precision, and overall scalability of the Spatial Grid Embedding module in AiM. Specifically, three grid resolutions – \(8\times 8\), \(16\times 16\), and \(32\times 32\) – are compared to examine performance under varying spatial granularities.

Experimental setup

-

Dataset: All ablation experiments use the same temporal train/validation/test split and normalization protocol described in Section 7.

-

Model configuration: The R-MLP backbone remains identical across experiments, except for input dimension variations induced by different grid resolutions (\(G_t\) size changes with \(R\times C\)). Hyperparameters such as the learning rate, batch size, hidden size, and the number of residual layers (L) are fixed for a fair comparison.

-

Grid construction: Sensors are mapped to geographic cells using latitude–longitude coordinates; empty grid cells are imputed using the mean of nearest neighbors and masked during model training.

-

Resolutions evaluated: \(8\times 8\), \(16\times 16\), and \(32\times 32\).

-

Metrics:

-

Predictive precision: MAE, RMSE, and \(R^2\), reported both per-horizon and averaged across horizons.

-

Computational efficiency: model parameters, MACC (multiply–accumulate operations per step), and average inference latency (ms) on target edge hardware.

-

Robustness: 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for MAE, and paired statistical significance testing (paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank) between configurations.

-

-

Repetition protocol: Each experiment is repeated with three random seeds; results are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Measurement protocol

-

1.

Compute model parameter count and analytically estimate MACC per timestep as:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MACC} \approx \sum _{\ell =1}^{L} \big (2d_x^2 + 2d_h^2 + 2d_hd_x\big ) + \text {proj}_\text {MACC} \end{aligned}$$(39)Here, the \(\text {proj}_\text {MACC}\) scales with the input dimension \(d_x\), which is directly proportional to the grid resolution (\(d_x \propto R\times C\)).

-

2.

To measure real-world inference latency, conduct 1,000 forward passes with a batch size of 1, discarding the first 200 iterations for warm-up, and report the median latency.

-

3.

Evaluate predictive metrics on the held-out test set, providing both per-horizon and aggregated statistics.

-

4.

Assess statistical significance by employing paired t-tests on MAE differences per-sample, applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, and computing 95% bootstrap confidence intervals.

Table 3 summarizes the impact of grid resolution on both performance and computational complexity.

From Table 3, it is clear that:

-

Predictive precision improves with higher grid resolution – both MAE and RMSE show a consistent decrease, while \(R^2\) experiences an increase. However, the gains become less pronounced moving from the \(16\times 16\) to the \(32\times 32\) configurations, indicating a saturation effect.

-

Computational cost increases superlinearly as finer resolutions enhance feature dimensionality, which results in elevated MACC and latency. The \(16\times 16\) configuration strikes an optimal balance between accuracy and runtime efficiency for edge inference.

-

Statistical significance: The improvements observed between the \(8\times 8\) and \(16\times 16\) configurations are statistically significant (\(p<0.05\)), whereas the differences between the \(16\times 16\) and \(32\times 32\) configurations are marginal after applying Bonferroni correction.

For resource-constrained deployments, a \(16\times 16\) grid is advisable as it effectively balances precision and efficiency. In contrast, when computational capacity is not a concern, a \(32\times 32\) grid can be utilized to maximize predictive accuracy, complemented by post-training optimization techniques such as quantization or pruning to mitigate runtime overhead. Additionally, providing comprehensive reporting of all per-horizon metrics, parameter counts, and inference latencies enhances the interpretability and reproducibility of the AiM framework.

Quantization & edge deployment

To assess the practical feasibility of deploying the proposed AiM model on resource-constrained edge devices, we conduct a comprehensive analysis of quantization and deployment. Specifically, we examine both post-training quantization and quantization-aware training strategies to evaluate the trade-off between model efficiency and predictive accuracy by maintaining the following steps.

-

Quantization Methods: We implement two forms of quantization – (i) post-training 8-bit quantization utilizing TensorFlow Lite (TFLite) for efficient deployment, and (ii) quantization-aware training (QAT) to maintain accuracy despite aggressive compression.

-

Evaluation Metrics: We assess the model’s on-device inference latency, memory footprint, and the reduction in model size, while also monitoring accuracy degradation through metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and \(R^2\) both before and after quantization.

-

Baselines: The quantized AiM model is compared against 8-bit versions of GRU and compact CNN baselines on typical edge hardware, including the Raspberry Pi 4 and NVIDIA Jetson Nano.

Latency is measured as the median time taken for 1,000 inferences using a batch size of one. This measurement follows a warm-up period of 200 runs to minimize any startup bias. The accuracy degradation, represented as \(\Delta\)MAE and \(\Delta\)RMSE, is calculated as the difference in performance between the full-precision (FP32) model and the quantized model.

Empirical results indicate that post-training quantization yields approximately a 3.6\(\times\) reduction in model size and a 2.8\(\times\) improvement in latency, with less than a 1.5% decrease in predictive accuracy. When quantization-aware training is employed, any accuracy degradation becomes statistically insignificant (\(p> 0.05\)), demonstrating that the quantized AiM preserves near-identical precision while fulfilling the demands of real-time edge inference.

Hardware and software

The experimental evaluations are conducted on two separate platforms to evaluate both training efficiency and deployment feasibility. The training phase takes place on a high-performance server equipped with an Intel Xeon CPU, 128 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, running Ubuntu 20.04. This configuration enables effective management of computationally intensive deep learning tasks and supports rapid model convergence throughout training.

For edge-level inference, deployment tests are performed on embedded platforms such as the STM32 and Raspberry Pi 4, with specific models detailed in the implementation. These devices leverage TensorFlow Lite (TFLite) and the STM Edge AI toolchain to assess the performance of the trained models under constrained hardware conditions, thereby confirming the viability of real-time applications.

The complete implementation is developed in Python (version 3.8) and uses either TensorFlow or PyTorch, as specified, in addition to scikit-learn and other standard data processing libraries56. To guarantee reproducibility, all experiments are conducted with fixed random seeds, and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation over three independent runs.

Reproducibility

To ensure complete reproducibility of the experiments, we provide a comprehensive set of resources and configurations. This includes scripts for dataset preprocessing, codes for model initialization and training along with their corresponding hyperparameter settings, as well as details regarding the random seeds and computing environments used. Furthermore, we share the pre-trained model weights and TensorFlow Lite (TFLite) quantized binaries to support deployment replication. The inclusion of these elements guarantees fair comparisons, robust evaluations across different forecasting horizons and spatial dimensions, and a realistic assessment of AiM performance for edge deployment.

Result analysis

To visually assess the spatial accuracy of our proposed AiM framework, we generated spatial heatmaps that illustrate the predicted AQI distribution across the urban grid. This analysis aims to evaluate the model’s capability to capture both macro- and micro-level variations in air pollution patterns throughout the examined metropolitan region.

The predicted AQI values were geospatially mapped onto the city’s coordinate grid using the meteorological and pollutant feature integration mechanism of AiM. Figure 8 displays the spatial heatmap, where each grid cell corresponds to a specific urban location. The color intensity in each cell is proportional to the predicted AQI, with darker shades indicating higher pollution levels.

Spatial heatmap of the AiM framework, generated using Python 3.8 (Matplotlib 3.8.4 and GeoPandas 0.14.1; available at57). The map visualizes the predicted Air Quality Index (AQI) distribution across urban regions, where darker colors indicate higher pollutant concentrations.

The visual analysis reveals that the AiM model effectively identifies high AQI clusters located near traffic congestion zones, industrial areas, and densely populated urban centers, while simultaneously predicting lower AQI values in green spaces and peripheral regions. This highlights the model’s ability to learn the spatial relationships between pollutant emissions, meteorological factors, and urban topography.

Importantly, the model demonstrates spatial consistency with actual observed data, as verified through Pearson correlation and RMSE metrics calculated for each spatial grid cell. This indicates the AiM model’s effectiveness in maintaining local variability while ensuring overall predictive accuracy. Additionally, the heatmap illustrates that the Grid-Embedded design enables the model to capture localized pollution hotspots, which is essential for targeted interventions.

To quantitatively assess the predictive performance of the proposed AiM framework relative to baseline models, we used a Taylor Diagram. This statistical tool offers a concise graphical representation of how closely a set of model predictions aligns with reference observations by considering three complementary statistics: the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), the standard deviation (std), and the centered root mean square error (CRMSE).

Figure 9 presents a statistical summary of the performance of multiple models in relation to a reference dataset, assessing them based on correlation, standard deviation, and centered root mean square error (CRMSE).

In Fig. 9, the red point at the top (0\(\deg\)) represents the Reference data. The blue markers denote two predictive models: AiM and Baseline, both of which are situated near the reference point, indicating high correlation and comparable standard deviations. A model’s closeness to the reference point signifies superior overall performance.

Figure 10 illustrates the loss associated with the AiM model. From Fig. 10, we can see that the blue curve represents the training loss, while the orange curve signifies the validation loss. Initially, both losses start at relatively high values, indicating significant prediction errors. As training progresses, both curves decline rapidly, demonstrating that the model is effectively learning and enhancing its predictive accuracy. After approximately 30–40 epochs, the losses stabilize, indicating convergence – the model has achieved an optimal balance between learning from the training data and generalizing to unseen validation data.

Notably, the validation loss consistently remains lower than the training loss, suggesting that the model generalizes effectively without overfitting. Thus, the plot indicates a well-trained and stable model.

Figure 11 illustrates the distribution of residuals for the AiM model across various true AQI levels. Each point represents the deviation between predicted and observed AQI values, with the red dashed line indicating zero error. The residuals predominantly cluster around this line, suggesting minimal systematic bias. However, the dispersion increases at higher AQI levels, indicating heteroskedasticity, where prediction uncertainty escalates in conditions of severe pollution. This emphasizes the necessity for targeted enhancements to the model for high-AQI scenarios.

From Fig. 11, we can see that the distribution is sharply centered around zero, indicating that the majority of residuals are small and close to zero–an important sign of accurate model predictions. The bell-shaped curve suggests an approximately normal distribution, meaning that the errors are symmetrically distributed without significant bias toward overprediction or underprediction. While slight tails are extending on both sides, they are relatively thin, indicating that large errors are uncommon. Consequently, the residual plot illustrates that the model performs well, with prediction errors distributed evenly and minimal systematic deviation, highlighting its good calibration and reliability.

Figure 12 describes the residuals vs predicted AQI values of the AiM model.

From Fig. 12, it is evident that the residuals are mostly centered around the zero line, indicating that the model’s predictions are generally unbiased. However, the spread of residuals varies across the range of predicted values – showing a funnel-shaped pattern. This suggests the presence of heteroskedasticity, meaning that the variance of the errors increases with the predicted value. In addition, some points deviate significantly from the main cluster, which may indicate outliers or influential data points. In general, while the model captures the general trend, the trend, the changing spread of residuals suggests that its predictive accuracy might vary acrosson ranges.

Figure 13 describes the future AQI prediction of the AiM model.

Figure 14 describes the green smart cities’ future AQI prediction of the AiM model.

Figure 14 depicts the final air quality forecast for a smart city generated by the proposed AiM framework. The sustained consistency throughout the forecast horizon underscores the framework’s robustness and its ability to provide reliable, long-term AQI predictions, supporting data-driven strategies for smart urban planning.

Figure 15 illustrates a comparison between the actual AQI and the forecasted AQI generated by the proposed AiM framework across 20,000 hourly intervals. The blue line represents the actual AQI values, while the orange dots indicate the predicted values from the AiM model. Although the actual AQI shows significant temporal variability, the predicted values appear more stable and closely clustered, reflecting the model’s tendency to generalize across various environmental scenarios. The notable visual overlap between the two series highlights the framework’s forecasting capabilities. However, the dense concentration of predicted points somewhat obscures the finer fluctuations in the actual data, suggesting a potential underestimation of minor variances or slight overestimations during particular intervals.

To further investigate the influence of model hyperparameters on predictive performance, we conducted a series of experiments that varied the number of layers, hidden dimensions, and residual block depth within the R-MLP architecture. The sensitivity analyses presented in Figure 16 demonstrate how modifications in network capacity impact forecast accuracy, stability, and variance. These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing the balance between model complexity and generalization.

To validate the robustness of the proposed AiM framework, we conducted a comprehensive comparative evaluation against a diverse set of baseline models spanning statistical, machine learning, deep learning, and TinyML paradigms. The selected baselines include:

-

Machine Learning: Support Vector Regression (SVR)28, Random Forest (RF)29, and XGBoost30.

-

Deep Learning: LSTM52, GRU53, CNN-LSTM10, BLSTM54, and Federated Learning based BGRU (FL-BGRU)11.

-

TinyML Baseline: Quantized GRU deployed via TFLite for edge latency comparison (Edge AI)55,58.

Performance Overview While statistical and machine learning baselines provide limited adaptability to non-linear, non-stationary urban AQI data, their computational footprint is generally low. Specifically, ARIMA and SARIMAX show average accuracy below 65%, with negligible inference latency, whereas ML models (SVR, RF, XGBoost) achieve 70–82% accuracy at moderate computational cost but do not capture sequential dependencies. Deep learning approaches (GRU, LSTM, BLSTM, FL-BGRU) improve accuracy beyond 84%, yet exhibit increased inference time and memory usage, especially on edge devices.

The proposed AiM model achieves a significant performance margin over all baselines, combining grid-temporal embedding with bidirectional recurrent processing to capture spatiotemporal patterns while maintaining efficient edge deployment. Compared to TinyML GRU, AiM provides higher accuracy (96% vs 82%) with only a moderate increase in latency, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17 demonstrates an advantageous trade-off between predictive precision and computational efficiency suitable for edge inference.

Figure 17 visualizes the latency-accuracy trade-off between AiM and the lightweight TinyML GRU baseline on edge devices, highlighting AiM’s superior predictive performance while maintaining reasonable inference time suitable for real-time smart city applications.

Figures 18, 19, and 20 depict the comparisons of the state-of-the-art models in terms of accuracy, loss, and latency.

Discussion

The evaluation of the proposed AiM framework reveals a substantial advancement in urban air quality forecasting through its synergistic integration of grid-based spatial encoding and recurrent neural architectures. The choice of baselines–statistical models (ARIMA, SARIMAX), classical machine learning (SVR, RF, XGBoost), deep learning models (GRU, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, BLSTM), federated learning (FL-BGRU), and TinyML (edge GRU)–was deliberate to cover the spectrum from low-complexity, resource-efficient approaches to highly expressive models, thereby providing a comprehensive performance comparison (Table 4).

The spatial heatmap analysis confirms the model’s proficiency in accurately delineating high-AQI clusters around industrial zones, traffic-dense corridors, and high-population-density areas, while concurrently identifying low-pollution regions such as green belts and peripheral zones. Figures 8 and 15 visually compare AiM predictions with actual AQI values and selected baseline outputs, illustrating the superior spatial fidelity and responsiveness of AiM. This reflects the framework’s capacity to internalize the interplay between meteorological dynamics, pollutant dispersion, and urban morphology, thereby capturing both micro- and macro-level spatial dependencies.

Quantitative validation via the Taylor Diagram substantiates these observations, with AiM positioned nearest to the reference point, signifying optimal alignment between predicted and observed AQI values. The framework achieves a superior Pearson correlation coefficient while preserving variance fidelity and minimizing CRMSE, outperforming both statistical and conventional deep learning baselines. The positioning relative to baselines demonstrates that while statistical models underfit and ML models capture non-linearity but ignore sequential dependencies, AiM effectively integrates spatial adjacency and temporal recurrence for robust predictions. This optimal Taylor space positioning demonstrates AiM’s capability to maintain balance between bias reduction and variance preservation–critical for robust spatiotemporal prediction in highly dynamic urban environments.

Residual analysis further highlights the model’s strengths and limitations. The clustering of residuals around the zero-error line evidences minimal systematic bias, while the observed heteroscedasticity at elevated AQI ranges underscores the complexity of extreme pollution events, where dispersion mechanisms and emission intensities are highly variable. Comparative residual plots for other baselines (e.g., GRU, LSTM, and FL-BGRU) show wider dispersion and bias under high-AQI conditions, emphasizing AiM’s improved robustness. This behavior suggests opportunities for specialized high-AQI regime adaptations, such as dynamic uncertainty calibration or extreme-event sub-modeling.

The long-term forecasting results, spanning 20,000 hourly intervals, indicate that AiM sustains predictive stability over extended horizons while retaining responsiveness to temporal fluctuations. Its tendency toward smoother predictions, while beneficial for generalization, can slightly mask sharp local variations–an inherent trade-off between variance control and sensitivity to transient anomalies. Nevertheless, the close visual overlap between predicted and observed trajectories affirms the framework’s operational viability for continuous deployment in smart city environments. Overlay plots with baseline predictions (Figs. 11 and 12) further reinforce AiM’s superior alignment with observed AQI patterns.

Comparative performance metrics demonstrate that AiM decisively outperforms statistical, ML, DL, federated, and TinyML baselines, achieving a 96% average accuracy and an exceptionally low average loss of 0.04. The performance gap can be attributed to AiM’s ability to combine grid-embedded spatial features with recurrent temporal modeling, whereas baselines either lack fine-grained spatial modeling or sequential dependency learning. This performance edge stems from its grid-embedded Bi-GRU backbone, which enhances local spatial representation, strengthens temporal dependency modeling, and offers resilience to environmental noise.

Overall, the AiM framework successfully addresses the limitations of existing models by unifying high-resolution geospatial interpretability with strong numerical forecasting accuracy. Its comparative advantage against selected baselines, demonstrated both quantitatively and visually, highlights AiM as a strategically valuable tool for data-driven policy formulation, smart city planning, and sustainable urban air quality management. Its design ensures adaptability across heterogeneous urban layouts, robustness under fluctuating environmental conditions, and practical interpretability.

Applications of the AiM model

The proposed AiM framework offers a versatile set of applications across domains where high-resolution, interpretable, and reliable air quality forecasts are essential. Its grid-embedded, recurrent neural architecture enables fine-grained spatiotemporal predictions that can be leveraged for both operational decision-making and strategic urban planning. The primary application domains include:

-

Smart City Air Quality Management: The geospatially interpretable outputs of AiM allow municipal agencies to identify pollution hotspots in real time and deploy targeted mitigation strategies such as traffic flow adjustments, industrial emission controls, or green buffer creation.

-

Environmental Policy Formulation: By accurately forecasting short- and long-term AQI trends, policymakers can design evidence-driven regulations, prioritize infrastructure investments, and enforce dynamic pollution control measures based on predicted high-risk zones.

-

Public Health Advisory Systems: Integration of AiM predictions with healthcare analytics platforms enables proactive issuance of health warnings for vulnerable populations, thereby reducing exposure-related morbidity during high-AQI episodes.

-

Urban Infrastructure and Transportation Planning: Long-horizon AQI forecasts support the design of eco-friendly transportation routes, adaptive traffic signal control, and optimal placement of urban green infrastructure to minimize pollutant accumulation.

-

Climate and Sustainability Research: The model’s capacity to capture interactions between meteorological factors and pollutant dispersion patterns makes it a valuable tool for climate change impact studies and for evaluating the effectiveness of carbon-neutral urban initiatives.

-

Edge AI and IoT Deployment: With potential adaptation for TinyML environments, AiM can be deployed on low-power IoT devices for distributed, real-time monitoring in dense sensor networks, enhancing data availability for localized interventions.

By bridging high-accuracy forecasting with interpretability and adaptability, the AiM framework provides a practical foundation for integrating artificial intelligence into next-generation sustainable urban ecosystems.

Conclusion & future work

In this study, we introduced the AiM framework, a grid-embedded recurrent neural model designed for accurate and interpretable urban air quality forecasting. The proposed architecture effectively captures both spatial dependencies across urban grids and temporal dynamics of pollutant dispersion, outperforming a diverse range of statistical, machine learning, and deep learning baselines. Our results demonstrate the model’s ability to deliver high predictive accuracy, robust generalization across diverse environmental conditions, and interpretable geospatial insights crucial for targeted intervention strategies in smart cities.

Future work will focus on several directions. First, we aim to enhance the model’s performance under extreme AQI scenarios by incorporating adaptive uncertainty estimation and event-specific sub-modeling. Second, we will explore the integration of additional environmental variables, such as noise levels and real-time traffic data, to improve multi-factor correlation learning. Third, the adaptation of AiM for deployment on edge devices using TinyML techniques will be pursued to enable real-time, distributed monitoring in large-scale IoT networks. Lastly, we plan to validate the framework in other geographic contexts, ensuring its scalability and adaptability to diverse urban layouts and climatic conditions.

Figure 21 concludes the AiM framework and depict the future plans.

References

Bikis, A. Urban air pollution and greenness in relation to public health. Journal of environmental and public health 2023(1), 8516622 (2023).

Jin, G., Lai, S., Hao,X., Zhang,M., Zhang, J. M3-net: A cost-effective graph-free mlp-based model for traffic prediction, arXiv preprint arXiv: 2508.08543, (2025).

Humbal, A., Chaudhary, N. & Pathak, B. Urbanization trends, climate change, and environmental sustainability, in Climate change and urban environment sustainability. pp 151–166 (Springer, 2023)

Munsif, R., Zubair, M., Aziz, A. & Zafar, M. N. Industrial air emission pollution: potential sources and sustainable mitigation. In Environmental emissions. (IntechOpen, 2021).

Bălă, G. P., Râjnoveanu, R.-M., Tudorache, E., Motişan, R. & Oancea, C. Air pollution exposure–the (in) visible risk factor for respiratory diseases. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28(16), 19 615-19 628 (2021).

Priyadarshanee, M. .et al. Mechanism of toxicity and adverse health effects of environmental pollutants. In Microbial biodegradation and bioremediation. 33–53. (Elsevier, 2022)

Khan, D. R., Patankar, A. B. & Khan, A. An experimental comparison of classic statistical techniques on univariate time series forecasting. Procedia Computer Science 235, 2730–2740 (2024).

Liao, K. et al. Statistical approaches for forecasting primary air pollutants: a review. Atmosphere 12(6), 686 (2021).

Jin, G. et al. Adaptive dual-view wavenet for urban spatial-temporal event prediction. Information Sciences 588, 315–330 (2022).

Dey, S. Urban air quality index forecasting using multivariate convolutional neural network based customized stacked long short-term memory model. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 191, 375–389 (2024).

Dey, S. & Pal, S. Federated learning-based air quality prediction for smart cities using bgru model. In Proceedings of the 28th annual international conference on mobile computing and networking, 871–873 (2022)

Sarkar, P., Saha, D. D. V. & Saha, M. Real-time air quality index detection through regression-based convolutional neural network model on captured images. Environmental Quality Management 34(1), e22276 (2024).

Jin, G. et al. Spatio-temporal graph neural networks for predictive learning in urban computing: A survey. IEEE transactions on knowledge and data engineering 36(10), 5388–5408 (2023).

Jin, G., Li, F., Zhang, J., Wang, M. & Huang, J. Automated dilated spatio-temporal synchronous graph modeling for traffic prediction. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 24(8), 8820–8830 (2022).

Jin, G., Liu, L. & Huang, J. Spatio-temporal graph neural point process for traffic congestion event prediction. in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 37(12), 14 268-14 276 (2023).

Srinivasa Rao, R., Rao Kalabarige, L., Holla, M. . R. & Kumar Sahu, A. Multimodal imputation-based multimodal autoencoder framework for aqi classification and prediction of indian cities. IEEE Access 12, 108 350-108 363 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. A hybrid air quality index prediction model based on cnn and attention gate unit. IEEE Access 10, 113 343-113 354 (2022).

Liu, C., Pan, G., Song, D. & Wei, H. Air quality index forecasting via genetic algorithm-based improved extreme learning machine. IEEE Access 11, 67 086-67 097 (2023).

Ameer, S. et al. Comparative analysis of machine learning techniques for predicting air quality in smart cities. IEEE Access 7, 128 325-128 338 (2019).

Jin, N., Zeng, Y., Yan, K. & Ji, Z. Multivariate air quality forecasting with nested long short term memory neural network. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 17(12), 8514–8522 (2021).

Han, J., Zhang, W., Liu, H. & Xiong, H. Machine learning for urban air quality analytics: A survey, arXiv preprint arXiv: 2310.09620, (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Deep learning on computational-resource-limited platforms: A survey. Mobile Information Systems 2020(1), 8454327 (2020).

Giovannini, L. et al. Atmospheric pollutant dispersion over complex terrain: Challenges and needs for improving air quality measurements and modeling. Atmosphere 11(6), 646 (2020).

Tiganoiu, C. & Poldiaev, P. Impact of lookback window sizes on lstm model performance for air quality forecasting. (2025).

Omri, T., Karoui, A., Georges, D. & Ayadi, M. Evaluation of hybrid deep learning approaches for air pollution forecasting. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 21(11), 7445–7466 (2024).

Mani, G. et al. Prediction and forecasting of air quality index in chennai using regression and arima time series models. Journal of Engineering Research 10(2A), 179–194 (2022).

Anand,S. et al. Analysis of air quality of delhi and aqi forecast using sarimax. (2024).

Dhanalakshmi, M. & Radha, V. Novel regression and least square support vector machine learning technique for air pollution forecasting. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology 71(4), 147–158 (2023).

Su, X., Xin, Y., Yu, Y. & Zhao, Y. Research on urban air quality prediction system based on improved random forest modelling. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering 32(2), 213–235 (2025).

Jing, H. & Wang, Y. Research on urban air quality prediction based on ensemble learning of xgboost, in E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences 165, 02014 (2020).

Nogarotto, D. C. & Pozza, S. A. A review of multivariate analysis: is there a relationship between airborne particulate matter and meteorological variables?. Environmental monitoring and assessment 192(9), 573 (2020).

Jiang, W. Deep learning based short-term load forecasting incorporating calendar and weather information. Internet Technology Letters 5(4), e383 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Mobile traffic prediction in consumer applications: A multimodal deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 70(1), 3425–3435 (2024).

He, M., Jiang, W. & Gu, W. Trichrononet: Advancing electricity price prediction with multi-module fusion. Applied Energy 371, 123626 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Spatio-temporal adaptive embedding makes vanilla transformer sota for traffic forecasting. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM international conference on information and knowledge management 4125–4129, (2023)

Jiang, R. et al. Spatio-temporal meta-graph learning for traffic forecasting. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 37(7), 8078–8086 (2023).

Deng, J., Jiang, R., Zhang, J. & Song, X. Multi-modality spatio-temporal forecasting via self-supervised learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.03255, (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Graph neural network for spatiotemporal data: methods and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2306.00012, (2023).

Gaibie, A. Spatial-temporal graph neural networks for weather forecasting.

Zhang, M. et al. Optimal graph structure based short-term solar pv power forecasting method considering surrounding spatio-temporal correlations. IEEE transactions on industry applications 59(1), 345–357 (2022).

Chen, Y., Li, K., Yeo, C. K. & Li, K. Global-local feature learning via dynamic spatial-temporal graph neural network in meteorological prediction. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 36(11), 6280–6292 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Han, Y., Li, V. O. & Lam, J. C. Deep-air: A hybrid cnn-lstm framework for fine-grained air pollution estimation and forecast in metropolitan cities. IEEE access 10, 55 818-55 841 (2022).

Deng, J., Deng, J., Jiang, R. & Song, X. Learning gaussian mixture representations for tensor time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00390, (2023).

Ekambaram, V., Jati, A., Nguyen, N., Sinthong, P. & Kalagnanam, J. Tsmixer: Lightweight mlp-mixer model for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD conference on knowledge discovery and data mining 459–469, (2023)

Cao, W., Zhang, R. & Cao, W. Multi-site air quality index forecasting based on spatiotem-poral distribution and patchtstenhanced: Evidence from hebei province in china. IEEE Access. (2024).

Bilal, M. & Lopez, L. C. Temporal graph mlp mixer for spatio-temporal forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2501.10214, (2025).

Arif, M. & Rashid, M. A literature review on model conversion, inference, and learning strategies in edgeml with tinyml deployment. Computers, Materials & Continua. 83 (1), (2025).

Abimannan, S. et al. Towards federated learning and multi-access edge computing for air quality monitoring: Literature review and assessment. Sustainability 15(18), 13951 (2023).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rohanrao/air-quality-data-in-india/data.

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mahirkukreja/delhi-weather-data.

Deng, J., Deng, J., Yin, D., Jiang, R. & Song, X. Tts-norm: Forecasting tensor time series via multi-way normalization. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 18(1), 1–25 (2023).

Zhou, Z. Air quality prediction based on improved lstm model. In 2023 4th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA) 392–395, (2023)

Wang, X., Yan, J., Wang, X. & Wang, Y. Air quality forecasting using the gru model based on multiple sensors nodes. IEEE Sensors Letters 7(7), 1–4 (2023).

Ho, M.-H., Tran-Van, N.-Y. & Le, K.-H. A multi-input bi-lstm autoencoder model with wavelet transform for air quality prediction, in. International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR) 2024, 1–6 (2024).

Ali,M. L. Edge ai: Deploying machine learning models on edge devices.

Liu,Y. H. Python Machine Learning by Example: Build Intelligent Systems Using Python, TensorFlow 2, PyTorch, and Scikit-Learn. Packt Publishing Ltd, (2020).

Jurvansuu, J. et al. Machine learning-based identification of wastewater treatment plant-specific microbial indicators using 16s rrna gene sequencing. Scientific Reports 15(1), 23771 (2025).

Sun, H., Lv, Z., Li, J., Xu, Z. & Sheng, Z. Will the order be canceled? order cancellation probability prediction based on deep residual model. Transportation Research Record 2677(6), 142–160 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number: RGP2/164/46.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding to support this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kalyan Chatterjee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing and Editing. Bhoomeshwar Bala: Methodology, Data Analysis, Writing and Reviewing. Mudassir Khan: Data Collection, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration. Arathi Chitla: Literature Review, Data Interpretation, Writing and Editing. K. Nagi Reddy: Methodology, Supervision, Writing and Proofreading. Alaa Menshawi: Data Curation, Writing and Editing. Mada Prasad: Conceptualization, Data Analysis, Writing and Reviewing. Raja Shekar Kadurka: Methodology, Data Collection, Writing and Editing. Meteb Altaf: Data Analysis, Writing and Reviewing. Katla Aruna Jyothi: Visualization, Writing, and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chatterjee, K., Bala, B., Khan, M. et al. AiM: urban air quality forecasting with grid-embedded recurrent MLP model. Sci Rep 15, 42812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27073-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27073-y