Abstract

Extracellular enzymes, released by coral holobionts (coral host, symbiotic dinoflagellates and associated microorganisms) are involved in nutrient cycling and can serve as diagnostic indicators of coral health and reef ecosystem functionality. For example, α-glucosidases (α-Glu), Leucine-aminopeptidases (LAP) and alkaline phosphatases (APA), hydrolyze large molecules into assimilable nutrients containing carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, respectively. This study investigated the extracellular activity (EEA) of these three enzymes in octocoral and hexacoral species under different environmental conditions. Results revealed that EEA from mucus-associated microbes was low, while entire coral holobionts exhibited significant activity. Furthermore, under identical environmental conditions and substrate concentrations, LAP activity was the highest, followed by APA and α-Glu, suggesting nitrogen and phosphorus limitation rather than carbon. Heat and light stress significantly influenced enzyme activities, with APA showing the strongest increase, reflecting an increased demand for phosphorus and adaptive strategies to mitigate phosphorus limitation. Finally, all three EEAs were much lower in octocorals than in hexacorals. By investigating the mechanisms controlling enzymatic activities in corals, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of coral physiology and nutrient metabolism in response to changing environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coral reefs are among the most productive and biologically diverse ecosystems on Earth despite thriving in nutrient-poor marine environments1,2. This apparent paradox is made possible by a highly efficient recycling of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon within the reef ecosystem. For example, the microbial decomposition of organic matter in the water column or sediment continuously releases nutrients back into the environment, which are then taken up by other organisms3. Sponges are also increasingly recognized as key ecosystem engineers, that efficiently retain and transfer energy and nutrients in the reef4. The symbiotic relationship between corals and their associated microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses and photosynthetic dinoflagellates from the Symbiodiniaceae family5,6, is also central to nutrient recycling in coral reefs7. Together, these organisms form a superorganism known as a holobiont8. Symbiodiniaceae photosynthesize, and convert sunlight and inorganic nutrients into organic compounds, which are transferred to the coral host, for its own energy needs9. In return, the coral host supplies the symbionts with carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen, and other nutrients derived from its metabolic waste, creating a highly efficient nutrient loop10. In addition, coral-associated bacteria and archaea are involved in various biogeochemical processes, such as nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification11,12.

Coral holobionts are also capable of releasing various extracellular enzymes in seawater, which break down complex organic molecules into smaller, more assimilable ones13,14,15,16,17. For example, leucine aminopeptidases (LAP) and α-glucosidases (⍺-Glu) hydrolyze proteins and carbohydrates into amino acids and sugars respectively, a potential source of nitrogen and carbon for corals and their algal symbionts. Significant LAP and ⍺-Glu activities have been measured in coral mucus, likely produced by the associated bacterial communities14,15,16. Alkaline phosphatases, in turn, are produced under phosphate deficiency (low levels of dissolved inorganic phosphorus DIP in seawater) in several marine organisms, including cyanobacteria18, benthic algae19, and dinoflagellates20,21. It breaks down phosphomonoesters into inorganic phosphate, that organisms can use for metabolic processes. As for the two other enzymes, alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) has been detected in isolated coral mucus, and was shown to be related to the heterotrophic activity of mucus-associated bacteria22,23. When measured in presence of the whole coral holobiont, APA was linked to Symbiodiniaceae photosynthesis, or to the nutritional status of the coral host13,17.

Despite their central role in nutrient recycling, our understanding of the drivers and variability of extracellular enzymatic activities (EEAs) in corals remains limited. Specifically, it is unclear how enzyme production differs across coral taxa (e. g. octocorals vs. hexacorals), whether it is modulated by the coral host or its symbionts, and how these activities respond to environmental stress. Addressing these knowledge gaps is crucial to better understand coral holobiont nutrition, and to scale up these processes to reef-wide nutrient cycling and ecosystem function, especially in the context of increasing nutrient imbalances and stressors in tropical oceans. Although previous studies have begun to investigate the production of EEAs by mucus-associated bacteria and coral holobionts, there are still significant knowledge gaps that require further investigation. To date, only one study16 has compared the production of multiple enzyme types by mucus-associated bacteria from the scleractinian coral Orbicella annularis. In contrast, the two studies focusing on coral holobionts only examined scleractinian species and specifically evaluated APA13,17. Consequently, there is a clear need for more comprehensive comparative studies examining multiple EEAs in a variety of coral species, including octocorals. Unlike hexacorals, octocorals are known to be more heterotrophic24,25,26, and often emerge as the predominant alternative community in many disturbed reefs27,28, as well as in eutrophicated, DOM-enriched reef ecosystems29,30,31. Hence, they may be more efficient in releasing extracellular enzymes in seawater to degrade the organic matter.

In this study, we performed laboratory experiments to investigate the activity of three extracellular enzymes (α-Glu, LAP, APA) in four symbiotic coral species belonging to the octocoral and hexacoral classes. The selected species represent two octocorals (Sarcophyton glaucum and Lobophytum sp.) and two hexacorals (Stylophora pistillata and Turbinaria reniformis) with contrasting ecological strategies. Sarcophyton glaucum and Lobophytum sp. are widespread soft corals commonly found in shallow reefs and are known for their heterotrophic capabilities. Stylophora pistillata is a branching scleractinian and an important reef builder in the Indo-Pacific and Red Sea, while Turbinaria is a plate-like coral often associated with mesophotic and turbid reef environments. This selection covers a diversity of functional traits and habitats, helping to generalize the results across coral types.

We first compared the EEAs under culture conditions (“control” condition; 25 °C and 200 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1), and then examined the effects of moderate heat (30 °C for 14 days) and light limitation (50 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1 for 24 days) on these activities. As these enzymes serve as proxies for C, N and P limitation in phytoplankton and microbial communities of the water column (e.g.20,32,33), they may also indicate whether coral holobionts are limited in one of these elements. Given the pronounced phosphorus limitation experienced by corals in natural environments compared to laboratory conditions, we also examined APA in several octocorals and hexacorals sampled on a Red Sea coral reef, across a depth gradient from 15 to 30–35 m depth. The EEAs can provide valuable insights into the nutrient acquisition strategies and the physiological state of coral holobionts under different environmental conditions. They can be used to better understand the environmental adaptability of coral species to the ongoing environmental changes.

Results

Laboratory experiments

Physiological differences between species in the control condition (26 °C and 220 µmol photons−1 m−2s−1)

The results of the statistical tests are reported in the Supplementary Material in Table S4, S5. Protein content per AFDW was overall 3 times lower in octocorals compared to hexacorals (p < 0.05; Fig. 1a), although the difference between Lobophytum and Stylophora was not significant. In addition, chlorophyll content per AFDW was ca. 3 times lower in octocorals than in hexacorals (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1b), due to a 10 times lower symbiont density in octocorals (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1c). However, when normalized to symbiont cell, chlorophyll content was 2 to 3 times higher in octocorals than in hexacorals (p < 0.01; Fig. 1d). Likewise, Pn, Rc and Pg normalized to AFDW were an order of magnitude lower in the octocorals (p < 0.05 for all; except between Lobophytum and Turbinaria for Rc; Fig. 2a–c). However, when normalized to symbiont cell, there was no difference in rates between octocorals and hexacorals (p > 0.05 for Pn, Rc, Pg; Fig. 2d–f). This suggests that the symbionts have similar photosynthetic capacities regardless of the coral species they are associated with.

Coral physiological parameters in the control condition (green plots), heat condition (red plots) and low light condition (blue plots). The boxplots represent protein content (mg g−1 AFDW) (a), total chlorophyll a and c2 content per AFDW (mg g−1 AFDW) (b), symbiont density (× 107 cells g−1 AFDW) (c) and total chlorophyll a and c2 content normalized to symbiont cells (µg 10−7 symbiont cells) (d). AFDW, ash-free dry weight. Sarcophyton and Lobophytum are octocorals while Stylophora and Turbinaria are hexacorals. The control condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the heat condition is 30 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the low light condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 50 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the control and stress conditions for each species (* for p < 0.05; ** for p < 0.01; *** for p < 0.001; **** for p < 0.0001). Significant differences between species within each condition are indicated by letters: plain letters (a, b) for the control, letters with apostrophes (a′, b′) for heat stress, and letters with double apostrophes (a″, b″) for low light.

Oxygen fluxes in the control condition (green plots), heat condition (red plots) and low light condition (blue plots). The boxplots represent net photosynthesis, respiration and gross photosynthesis rates, normalized to AFDW (a–c, respectively; µmol O2 g−1 AFDW h−1), as well as normalized to symbiont cells (d–f, respectively; µmol O2 10−7 symbiont cells h−1). AFDW, ash-free dry weight. Sarcophyton and Lobophytum are octocorals while Stylophora and Turbinaria are hexacorals. The control condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the heat condition is 30 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the low light condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 50 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the control and stress conditions for each species (* for p < 0.05; ** for p < 0.01). Significant differences between species within each condition are indicated by letters: plain letters (a, b) for the control, letters with apostrophes (a′, b′) for heat stress, and letters with double apostrophes (a″, b″) for low light.

Effect of temperature and irradiance on coral physiology

The results of the statistical tests are reported in the Supplementary Material in Table S4, S5.

No significant effect of temperature was observed on the physiological parameters and oxygen fluxes of the two octocoral species, or Stylophora (Figs. 1 and 2). However, following a 10-day gradual increase, a 14-day exposure to heat stress at 30 °C increased the respiration rates normalized to AFDW or symbiont cell in Turbinaria (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 2b, e), resulting in a 70% increase in Pg (per AFDW, p < 0.05 and per symbiont cell, p < 0.05; Fig. 2c, f).

A 24-days exposure to low light levels had a significant impact on the physiology of all species studied. Although symbiont density was not affected in octocorals, chlorophyll content per AFDW decreased by 30% under low light in Sarcophyton (p < 0.05; Fig. 1b), resulting in a collapse in Pn (both per AFDW, p < 0.01 and per symbiont cell, p < 0.01; Fig. 2a, d), a 60% decrease in Pg (both per AFDW, p < 0.05 and per symbiont cell, p < 0.01; Fig. 2c, f), and a 30% decrease in Rc (per AFDW, p < 0.05; Fig. 2b, e). In Lobophytum, even though chlorophyll content per AFDW increased by 50% (p < 0.001; Fig. 1b), a collapse in Pn (both per AFDW, p < 0.05, and per symbiont cell, p < 0.05; Fig. 2a, b) and a decrease in Pg (both per AFDW—40%, p < 0.05, and per symbiont cell—60%, p < 0.05; Fig. 2c, f) was observed. Both octocoral species also showed a 40% decrease in the P:R ratio (the contribution of photosynthesis to the respiratory requirements, p < 0.001; shown in Supplementary Material Fig. S3). Among hexacorals, chlorophyll content in Stylophora almost doubled (both per AFDW, p < 0.05, and per symbiont cell, p < 0.01; Fig. 1b, d) in the low light condition, but a 80% decrease in Pn (per AFDW, p < 0.05; Fig. 2a) was still observed, along with a 50% decrease in Rc (per AFDW, p < 0.05; Fig. 2b) resulting in a Pg reduced by 60% (per AFDW, p < 0.05; Fig. 2c). Turbinaria was the only species whose symbiont density decreased by half under low light condition (p < 0.001; Fig. 1b), but doubled its chlorophyll content per symbiont cell (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1d), thus maintaining its Pn and Pg at low light at levels comparable to the control (p > 0.05; Fig. 2d, f).

Protein content was the only physiological parameter which was neither affected by temperature nor by low light compared to the control, for all species studied (p > 0.05; Fig. 1a).

EEAs of corals in laboratory experiments

The results of the statistical tests are reported in the Supplementary Material in Table S6, S7. EEAs normalized to protein content are also available in the Supplementary Material Fig. S4a-f. This normalization gave similar results to the AFDW normalization, presented below.

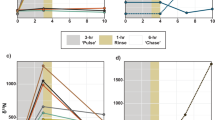

The EEAs of the mucus were negligible compared to the coral holobiont, for all species and for all three enzymes tested (p < 0.01; Supplementary Material Fig. S5a–f). In the coral incubations, ⍺-Glu activity was overall lower than APA which in turn was lower than LAP activity, for the same amount of substrate and in all species tested (Fig. 3a–f), except in Turbinaria, where ⍺-Glu activity was comparable to that of APA. Additionally, EEAs were one (APA, LAP) to two (⍺-Glu) orders of magnitude lower in octocorals compared to hexacorals species (p < 0.0001 for all enzymes studied).

EEAs in laboratory experiment, by corals from the control condition (green plots), heat condition (red plots) and low light condition (blue plots). The boxplots represent α-Glucosidase activity (α-Glu, nmol MUF mg−1 AFDW h−1) in octocorals (a) and hexacorals (b), Alkaline phosphatase activity (APA, nmol p-NP mg−1 AFDW h−1) in octocorals (c) and hexacorals (d), and Leucine-aminopeptidase activity (LAP, nmol AMC mg−1 AFDW h−1) in octocorals (e) and hexacorals (f.). AFDW, ash-free dry weight; EEAs, extracellular enzymatic activities. Sarcophyton and Lobophytum are octocorals while Stylophora and Turbinaria are hexacorals. The control condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the heat condition is 30 °C and an irradiance of 220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1; the low light condition is 26 °C and an irradiance of 50 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the control and stress conditions for each species (* for p < 0.05; ** for p < 0.01; *** for p < 0.001; **** for p < 0.0001). Significant differences between species within each condition are indicated by letters: plain letters (a, b) for the control, letters with apostrophes (a′, b′) for heat stress, and letters with double apostrophes (a″, b″) for low light. For all enzymes and conditions tested, EEAs were significantly higher in both hexacorals compared to both octocorals.

Temperature increased ⍺-Glu activity in hexacorals, by 30 to 80% for Stylophora and Turbinaria, respectively, (p < 0.01, Fig. 3b), but not for the octocorals (Fig. 3a). Increased temperatures further doubled APA in both octocorals and hexacorals (p < 0.05, Fig. 3c, d). Under low light condition, ⍺-Glu activity in octocorals decreased by a factor of two (p < 0.05, Fig. 3a), while APA in hexacorals increased by a factor of two (p < 0.05, Fig. 3d). Neither temperature nor low light significantly affected LAP activity in any of the species studied (Fig. 3e, f).

APA in the field experiment

The results of the statistical tests are reported in the Supplementary Material in Table S7.

The APA of octocorals in the Red Sea was one order of magnitude lower than that of hexacorals at both depths studied (p < 0.0001; Fig. 4a, b). In octocoral species, APA neither differed between shallow coral species (p > 0.05), nor between depths for each species (p > 0.05; Fig. 4). However, APA was two-times higher in deep Rythisma than in deep Sarcophyton (p < 0.05, Fig. 4a).

APA measured in the field (Red Sea), in corals from shallow depth (yellow plots) and mesophotic depth (“deep”, blue blots). The boxplots represent Alkaline phosphatase activity (APA, nmol p-NP mg−1 protein h−1) in octocorals (a) and hexacorals (b). Sarcophyton, Xenia and Rythisma are octocorals while Stylophora, Galaxea and Turbinaria are hexacorals. Asterisks indicate significant differences between shallow and deep condition for each species (**** for p < 0.0001). Significant differences between species within each depth are indicated by letters: plain letters (a, b) for shallow corals and letters with apostrophes (a′, b′) for deep corals. The APA measured was significantly higher in all hexacorals compared to all octocorals tested, for both depths. No data collected for Xenia from mesophotic depth.

In shallow hexacorals, APA was two-times lower in Stylophora and Turbinaria than in Galaxea (p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively, Fig. 4b). APA increased three-fold in deep Stylophora (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4b), and was therefore two times higher than in Galaxea (p < 0.05) and three-times higher than in Turbinaria (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4b).

When comparing APA measured in the field and in the laboratory experiment (normalized to protein content) APA was 3, 8–20 and 6 times higher in situ for Sarcophyton, Stylophora, and Turbinaria respectively (p < 0.0001 for all three species; Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Material Fig. S4e, f).

Discussion

Coral reefs thrive in nutrient-poor environments through efficient nutrient cycling, but the role of extracellular enzymatic activities (EEAs) in coral nutrient acquisition remains poorly understood. Our results show that hexacoral holobionts consistently produced higher EEAs than octocorals, with LAP being the most produced enzyme in all species, followed by APA and ⍺-Glu. APA responded significantly to both heat stress and light limitation, indicating an increased phosphorus requirement in response to environmental changes. These patterns highlight the species-specific metabolic requirements and the potential of EEAs as indicators of coral nutritional needs.

Baseline differences in EEAs between coral taxa

Under the control condition, tissue parameters (symbiont density, protein and chlorophyll concentrations; Fig. 1) and oxygen fluxes (net and gross photosynthesis; Fig. 2) normalized to AFDW were significantly lower in octocorals compared to hexacorals, as previously observed in comparative studies26,34. This is in agreement with the low rates of dissolved carbon and nitrogen assimilation observed in previous studies26,34,35,36, overall suggesting a lower metabolism compared to hexacorals.

The results of this study also show that EEAs were two-fold (normalized to protein content; Fig. S4) to ten-fold (normalized to AFDW; Fig. 3) lower in octocorals than hexacorals. This difference in EEAs was not linked to the activity of the mucus-associated bacteria, which was significantly lower than the activities measured for the coral holobiont (Fig. S5), in agreement with the results obtained for Acropora (α-Glu and LAP15) and Stylophora (APA,17). These results suggest that the three enzymes were mainly released by the coral holobiont in our experiment, although bacteria in the mucus can also greatly contribute to the recycling of organic matter in the reef, by producing a wide range of different enzymes16.

Differences in EEAs between octo-and hexacorals could thus be related to the lower metabolism and nutrient requirements of octocorals, which do not need to spend large amounts of energy for calcification, contrary to hexacorals35. It can also be linked to the microorganism community associated with the tissues of octo- and hexacorals, since different Symbiodiniaceae genotypes can exhibit different APA13. Further studies are therefore needed to better understand which factor(s) and coral partner modulate EEAs in corals.

α-Glu and LAP activities have mainly been studied when released by bacteria or cultivated from coral mucus14,15,16. Therefore, direct comparisons with the activities measured in this study at the holobiont level should be done with caution. Results obtained with APA in this study are consistent with previous measurements performed with the hexacoral species Stylophora acclimated to similar light conditions (150 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1) and incubated in darkness (Fig. S4f ; APA: 15–20 nmol p-NP mg−1 protein h−1 in13). Under identical culture conditions and substrate concentrations, α-Glu activity was consistently half that of APA, which in turn was three times lower than LAP activity across all coral species examined (Fig. 3a–f). This pattern reflects a general trend observed in marine ecosystems in which organisms are more limited in nitrogen and phosphorus than in carbon37. In corals, carbon is indeed abundantly supplied by symbiont photosynthesis, covering more than 90% of the energy needs of the coral host under control conditions9. Although nitrogen can be acquired through the uptake of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) by the Symbiodiniaceae or through biological nitrogen fixation by diazotrophs associated with the coral holobiont38,39, symbionts are often considered N-limited, which favors the utilization of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) through the production of enzymes such as LAP. In contrast, phosphorus cannot be biologically fixed and must be taken up directly from the surrounding environment. This makes P acquisition particularly challenging in oligotrophic reef systems, where phosphate concentrations are typically very low (0.05–0.5 µM), while DIN concentrations are often an order of magnitude higher (0.1–2 µM). Therefore, coral holobionts are often P-limited40,41,42, although phosphorus plays an important role in biological processes such as ATP synthesis and energy transfer43. Previous studies have shown that phosphorus limitation in coral holobionts leads to increased APA activity, suggesting that holobionts release this enzyme to scavenge the phosphorus contained in complex organic molecules dissolved in seawater13,17. Finally, LAP activity, which hydrolyze proteins into smaller and more bioavailable molecules such as amino acids, was consistently the highest in all corals studied, reaching nearly 20 nmol AMC mg−1 AFDW h−1 or 45 nmol AMC mg−1 protein h−1 in hexacorals (Fig. 3f, Fig. S4d). This aligns with the higher nitrogen demand relative to phosphorus of coral holobionts, as reflected in their tissue N :P ratios (N:P = 25–45;17,26), and supports the idea that enzyme activities reflect the relative nutrient demands and availability in the coral environment.

Enzymatic responses to heat stress

Two weeks exposure to elevated temperature did not significantly affect tissue parameters and oxygen fluxes normalized to AFDW in any of the coral species studied, except for increased respiration rate in Turbinaria (Figs. 1 and 2). However, heat stress induced a significant increase in APA in all coral holobionts examined, as well as an increase in α-Glu activity in hexacorals, albeit to a lesser extent than APA (Fig. 3a–d). Such an increase in enzymatic activities can be due to a direct temperature effect on the enzymatic activities, or to a higher metabolic activity of the coral holobiont under elevated temperatures44,45,46. A higher APA and α-Glu activity may also be representative of a higher requirement in phosphorus and carbon by the coral holobionts. In the case of phosphorous, this hypothesis is consistent with previous studies that have reported higher uptake rates of dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) under elevated temperatures in multiple coral species47,48. Enhanced DIP uptake helps corals mitigate bleaching, as phosphorus limitation can compromise the integrity of symbiont thylakoid membranes, reducing their capacity to manage reactive oxygen species (ROS). This impairment increases their susceptibility to heat-induced bleaching48,49,50. As for APA, the higher α-Glu activity may indicate an increased demand for carbon, potentially driven by increased respiration rates or mucus secretion as a protective response to heat stress51,52. However, the increased respiration rates was only observed in Turbinaria, while Stylophora did not show significant changes in respiration or P:R ratio, suggesting either a lower metabolic adjustment or the use of alternative metabolic pathways to maintain carbon balance, such as mucus secretion (Fig. 2, Fig. S3). The observed increase in EEAs under stress strongly suggests that coral holobionts can upregulate enzyme production to maintain nutrient homeostasis within their tissues. In contrast to APA and α-Glu, LAP activity did not change under heat stress for all coral species studied (Fig. 3e, f). This is consistent with the observation that uptake rates of dissolved organic and inorganic nitrogen by corals under heat stress either decreased26,47,48, or increased35,47 depending on the intensity of the stress and the coral species considered. In addition, elevated temperatures have been shown to stimulate nitrogen fixation by diazotrophic bacteria associated with corals38,39, potentially increasing nitrogen availability to the holobiont and further supporting a shift in the nutrient limitation balance toward phosphorus under heat stress. In contrast to the above observations, LAP activity in coral mucus consistently increased under high temperature, maybe due to a proliferation of microorganisms14,15.

Light limitation and species-specific adjustment strategies

In contrast to heat stress, light limitation induced significant and species-specific changes in coral physiology (Fig. 1). Each coral species developed different strategies to cope with environmental fluctuations53,54. Lobophytum, Stylophora and Turbinaria acted as regulators, by adapting internal physiological traits (e. g. chlorophyll content, symbiont density) to maintain their physiological functions under reduced light. Indeed, Stylophora and Lobophytum increased their chlorophyll content normalized to AFDW under reduced light (as observed in55,56), while Turbinaria decreased its symbiont density, resulting in increased chlorophyll content normalized to symbiont cell (Fig. 1c, d). In contrast, Sarcophyton behaved like a conformer, adapting its internal state to environmental conditions (Fig. 1b).

Low irradiance also affected enzymatic activity: APA significantly increased in hexacorals, albeit to a lesser extent than under heat stress (Fig. 3d). A similar trend was observed by13 in corals acclimated to darkness. The mechanisms driving APA upregulation remain to be clarified but may reflect enhanced P demand under low-light conditions. This increased demand could be related to the rise in chlorophyll content normalized to symbiont density in both hexacorals, as chlorophyll synthesis and the production of associated phospholipids may require additional phosphorus. The ⍺-Glu activity was decreased under light limitation in octocorals (Fig. 3a), although it was already very low in these corals under control conditions, while LAP activity appeared to be unaffected by variations in light intensity (Fig. 3e, f). Further experimentation is imperative to unravel the intricate interplay between irradiance levels and EEAs in coral symbioses. These investigations could offer invaluable insights into the adaptive mechanisms employed by corals in response to fluctuating environmental conditions.

Over their lifetimes, corals are exposed to a range of environmental stressors. Our findings suggest that light reduction primarily induces P limitation, as indicated by increased APA, whereas heat stress seems to trigger both P and C limitation, reflected in the upregulation of APA and α-Glu. Such targeted enzymatic adjustments align with a regulator life-history strategy, whereby corals actively modulate nutrient acquisition mechanisms to maintain internal homeostasis under changing conditions.

Field evidence and the role of symbiont clade in APA variability

Measurements of APA in hexacorals and octocorals directly sampled in the reefs of Eilat (Red Sea) confirm our laboratory results with much lower EEAs in octocorals than hexacorals (Fig. 4a, b). Significantly higher APA levels in corals directly sampled in the field compared to those obtained under laboratory conditions, suggest a higher degree of P-limitation on the coral reefs of Eilat (DIP < 0.2 µM, data from Israel National Monitoring Program of the Gulf of Eilat, http://www.iui-eilat.ac.il/Research/NMPMeteoData.aspx), thus supporting the hypothesis that APA may serve as a proxy for P availability in corals. Red Sea corals exhibited similar APA levels (83 nmol P cm−2 h−1 in shallow Stylophora (Table S3)) to those reported for the total coral reef benthos (57: 41.6 to 416 nmol P cm−2 h−1). These results point towards a substantial contribution of coral holobionts to APA in reef environments.

Finally, among the species studied, only Stylophora holobiont showed increased APA at 30 m depth compared to shallower depth (Fig. 4b). Notably, it is also the only species in our study known to shift its Symbiodiniaceae community with depth in Eilat, with Symbiodinium being predominant in shallow waters, and Cladocopium in deeper waters (> 25 m)58,59. In contrast, the other five species sampled in situ (Sarcophyton, Rythisma, Xenia, Turbinaria and Galaxea), as well as Lobophytum (used in the laboratory), typically host Cladocopium as the predominant Symbiodiniaceae clade at both depths660 and showed no variation in APA. This supports the hypothesis that clade-specific traits of Symbiodiniaceae may influence enzymatic production capacity, including APA production13,17,20. However, no study to date has directly compared P requirements across Symbiodiniaceae clades. Thus, we can only hypothesize that such nutrient demands are species-specific and may relate to differences in metabolic rate or nutrient storage capacity. Future studies are needed to test whether such clade-level differences drive enzymatic activity patterns across broader environmental gradients and coral taxa.

Conclusion

Extracellular enzymatic activities in coral reef ecosystems play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, symbiotic interactions, and ecosystem resilience. Our experiments of EEAs under heat stress or light reduction reveals significant changes in enzyme activities, with APA emerging as the most responsive enzyme. Its increase in many coral holobionts under both stressors suggests an increased requirement for phosphorus and highlights the adaptive strategies of corals to mitigate phosphorus limitation. Our results also suggest that APA may be primarily produced by Symbiodiniaceae rather than by mucus-associated bacteria, reinforcing the idea that enzymes are part of a symbiont-driven nutrient regulation mechanism rather than microbial recycling. In addition, we demonstrated that octocoral holobionts have much lower EEAs production than hexacoral (Scleractinia) holobionts, both under laboratory and in situ conditions. This is in line with lower photosynthesis and uptake rates of dissolved nutrients by octocorals. By identifying how enzyme activity reflects nutrient demands and stress responses, this study offers valuable insight into the nutritional diversity of coral holobionts and their contributions to reef-scale nutrient cycling, which are key processes underpinning the resilience and adaptability of coral reef ecosystems in a changing ocean.

Material and methods

Laboratory experiment

Biological material and experimental setup

Experiment was performed with coral colonies originating from the Gulf of Aqaba (Red Sea). Six colonies of the octocoral species (Malacalcyonacea) Sarcophyton glaucum (Quoy & Gaimard, 1833) and Lobophytum sp. (Marenzeller, 1886), and six colonies of the hexacoral species (Scleractinia) Stylophora pistillata (Esper 1797) and Turbinaria reniformis (Bernard, 1896), were used to generate 18 coral nubbins per species (3 coral nubbins from each colony). In the following sections and figures, we will refer to Sarcophyton glaucum and Lobophytum sp. as Sarcophyton and Lobophytum, respectively. Similarly, Stylophora pistillata and Turbinaria reniformis will be referred to as Stylophora and Turbinaria. Nubbins were kept in 6 × 20-L aquaria for 5 weeks until recovery (3 nubbins species−1 aquarium−1 from different colonies) and fed with Artemia nauplii twice a week. They were kept at 26 ± 0.2 °C under a photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 220 ± 10 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1, and a 12:12 photoperiod. The aquaria were continuously supplied with natural seawater at a flow rate of 20 L h−1, and the temperature was controlled by submersible resistance heaters (Visi-Therm VTX 300 W, Aquarium Systems, France) and temperature sensors (Ponsel, France), while light was provided by HQI lamps (Tiger 230 V/50 Hz 250 W, Faeber, Italy) above each aquarium. Submersible pumps (NJ600—230 V/50 Hz 7W, New Jet, Italy) were also used to ensure proper water mixing.

After the recovery phase, aquaria were divided into three sets of 2 aquaria each (with 6 nubbins per species from different colonies in each set) in which 3 different environmental conditions were applied (Fig. 5). The first set, the control condition (“Control”), was kept at 26 °C and a PAR of 220 ± 10 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1, reflecting the conditions at which the corals have been cultured. The second set was exposed to a moderate heat stress (“Heat stress”), with temperature increasing at a rate of 0.4 °C per day until reaching 30 °C after 10 days, and corals were then kept for two weeks at this temperature before measurements started. The irradiance was kept at the level of the control condition. The third set of aquaria (“Low light”) was maintained at 26 °C, but coral nubbins were exposed to low PAR (50 ± 10 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1) for 24 days before measurements began. This light intensity was chosen as it is close to the irradiance found at 30–40 m depth (“upper mesophotic corals”) in the Red Sea25. Temperature in this set was kept at the control temperature, (26 °C), since temperature is often comparable between shallow and upper mesophotic depth in situ (Israel National Monitoring Program of the Gulf of Eilat, http://www.iui-eilat.ac.il/Research/NMPMeteoData.aspx). For both heat stress and low light treatments, enzymatic and physiological measurements were performed after an average of 24 days of total exposure, ensuring comparability between the stress conditions and the control. Corals were fed twice a week during the first 14 days of acclimatization. However, feeding was then stopped 10 days before the start of the measurements to avoid any interaction with the enzymatic assays. After acclimation in the different environmental conditions, two different sets of measurements were performed:

Experimental design for extracellular enzymatic activities (EEAs) measurement. (1) First experiment: Release of EEAs (APA, LAP, ⍺-Glu) by the mucus-associated microorganisms in corals (Sarcophyton, Lobophytum, Stylophora and Turbinaria) maintained in control condition (n = 6 per species) and FSW (n = 3) as a control for any non-enzymatic hydrolysis of the substrate. (2) Second experiment: Effect of temperature and low light on APA, LAP, ⍺-Glu in corals (Sarcophyton, Lobophytum, Stylophora and Turbinaria) (2.a; n = 6 per species and condition) and on their physiology (2.b; n = 6 per species and condition). (3) Third experiment: Effect of a depth gradient on the APA in corals (Sarcophyton, Rythisma, Xenia, Stylophora, Turbinaria and Galaxea) on the field (IUI, Red Sea) (n = 6 per species and depth; no data collected for Xenia from mesophotic depth). Substrate was added at a final concentration of 250 μM in each beaker. APA, alkaline phosphatase activity; FSW, filtered seawater; LAP, leucine-aminopeptidase; Leu-AMC, Leucine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride; p-NPP, para-nitrophenyl phosphate; α-Glu, ⍺-glucosidase; α-MUF, 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-glucopyranoside. Sarcophyton., Sarcophyton glaucum; Lobophytum., Lobophytum sp.; Stylophora., Stylophora pistillata; Turbinaria., Turbinaria reniformis; Xenia., Xenia sp.; Rythisma., Rythisma fulvum; Galaxea., Galaxea fascicularis.

The first set of measurements tested whether alkaline phosphatase, LAP and α-Glu were produced by the mucus-associated microorganisms or by the entire coral holobiont. Nubbins from the control condition (n = 6 per species) were incubated in the light (220 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1) at 26 °C in individual 50-ml beakers containing 0.22-µm filtered seawater (FSW), for 5 h to release mucus (Fig. 5). They were then removed from the beakers, leaving the mucus behind. The substrate corresponding to the enzyme tested (p-NPP, Leu-AMC or α-MUF, respectively) was added and the beakers were then incubated in the dark, with stirring, for another 5 h. Since the incubation seawater was pre-filtered on 0.22 µm, the production of EEAs corresponded primarily to the bacteria naturally contained in the mucus of the different coral species. Since mucus produced very little EEAs (see results Sect. “EEAs of corals in laboratory experiments”), the following experiments were performed on whole coral nubbins.

The second set of measurements therefore tested the individual effects of light and temperature on the physiology (as described in following Sect. “Photosynthesis and respiration measurements” and “Sample processing and data normalization”) and EEAs of corals. For EEAs, the three enzyme assays were performed on the same nubbins, from different colonies, with a 72-h interval between each assay (n = 6 nubbins per species and experimental condition; Fig. 5). Incubations with substrate were performed in the dark, but the temperature was changed depending on the experimental condition (26 °C or 30 °C). Enzymatic measurements were then performed as described in Sect. “Enzymatic assays”, with water subsamples being taken at the beginning and end of incubation. At the end of the incubations, all nubbins were used for physiological measurements (see following sections).

Enzymatic assays

Measurement of alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) is based on the hydrolysis of para-nitrophenyl phosphate (p-NPP) into para-nitrophenol (p-NP) and hydrogen phosphate by the enzyme61. The p-NP molecule produced displays a yellow coloration at pH = 11, whose absorbance can then be measured at 400 nm using a spectrophotometer. Furthermore, the production of p-NP molecules is proportional to the amount of p-NPP cleaved, providing a reliable quantification of APA. Leucine-aminopeptidase (LAP) and α-glucosidase (α-Glu) activities are measured by spectrofluorometry. Measurements rely on the fluorescence emitted by molecules upon excitation in the violet-blue light range. In the presence of LAP, L-Leucine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride (Leu-AMC) is hydrolyzed into leucine (containing 1 atom of N and 6 atoms of C) and 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC), a fluorescent compound sensitive to light. LAP hydrolysis therefore provides both nitrogen and carbon. Similarly, in the presence of α-Glu, 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (α-MUF) is hydrolyzed into glucopyranose (containing 6 atoms of C) and 4-methylumbelliferone (MUF), a fluorescent compound33. As for APA, the production of AMC and MUF is directly proportional to the hydrolysis of Leu-AMC and α-MUF, respectively.

Assays consisted in adding 250 µM of the substrates (p-NPP, Leu-AMC or α-MUF) in 50-ml beakers containing either a small coral nubbin (1 cm3), mucus or 0.22 µm filtered seawater (FSW) as a control to account for any non-enzymatic hydrolysis of the substrate. Previous studies13,14 have established that a concentration of 250 µM of substrate allows for a maximum extracellular enzyme activity (EEA). Preliminary tests showed that enzyme activity increased during an incubation time of 7 h in the dark, before reaching a stability zone (⍺-Glu and LAP: Supplementary material Fig. S1a, b; APA: Supplementary material in17). We therefore chose an incubation time of 5 h in our experiments in order to measure a significant enzyme activity within a relatively short exposure time for the corals. To ensure sufficient exchange of oxygen between air and seawater, seawater was slightly shaked during the incubations (Supplementary material Fig. S1c). We ensured that the level of oxygen in seawater did not drop by more than 15% at the end of the 5-h incubation. After incubation, corals were transferred back to their respective aquaria (see below) until further processing. Corals had all their polyps open 2 h after their transfer and none of them showed any sign of stress. For each enzyme tested, three subsamples of 1 mL (APA) or 0.5 mL (for LAP and α-Glu) were taken immediately after addition of the substrate and at the end of incubation in the dark and filtered through a 0.22-µm PES filter syringe.

For APA, the subsamples were immediately alkalinized with 125 µL of NaOH 1 M to stop the enzymatic reaction and raise the pH to 11 for optimal coloration of pNp, then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min (adapted from13,17). The absorbance was read at 400 nm in transparent 96-well plates using a spectrophotometer (Xenius®, SAFAS, Monaco) and confronted to the calibration curve generated by measuring the absorbance of a known range of p-NP concentrations from 0 to 80 µM (Supplementary Material Fig. S2a). APA was calculated from the production of p-NP during the 5-h incubation, after correction with the control (see Supplementary Material for equations). For LAP and α-Glu activities, the filtered subsamples were immediately stabilized by adding 187.5 µL of Tris–HCl buffer at pH = 10.8, to maintain maximal fluorescence intensity14. Fluorescence intensity was then measured in opaque 96-well plates using a spectrofluorometer (Xenius®, SAFAS, Monaco), at wavelengths of 440–450 nm for both LAP and α-Glu, under an excitation of 356 nm and 364 nm, respectively14,33. Concentrations were calculated based on calibration curves generated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of a known range of AMC and MUF solutions, from 0 to 30 µM (Supplementary Material Fig. S2b, c). LAP and α-Glu activities were calculated from the production of AMC and MUF, respectively, during the 5-h incubation, after correction with the control (see Supplementary Material for equations).

All three enzymatic assays (APA, LAP, α-Glu) were performed sequentially on the same coral nubbins, with a 72-h interval between each measurement. APA was always tested first, followed by LAP and then α-Glu. As a result, APA was measured after the shortest food deprivation period (10 days), while α-Glu was measured last (after 15 days of food deprivation and two prior incubations). This standardized order was applied across all experimental conditions to ensure comparability of each enzyme between treatments. The fact that LAP, the second enzyme tested, consistently showed the highest activity, suggests that assay order or successive incubations didn’t affect the measurements performed.

Photosynthesis and respiration measurements

Net photosynthetic rates (Pn) were estimated under a PAR of 220 ± 10 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1 (for the Control and Heat stress condition) or 50 ± 10 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1 (Low light condition). Respiration rates (Rc) were measured in the dark, immediately following the Pn measurements. For this purpose, 6 nubbins from each experimental condition and species were individually placed in 50-mL Plexiglas chambers hermetically sealed, stirred, and filled with 0.22-µm FSW, at 26 °C or 30 °C, depending on the experimental condition. Each chamber was connected to an oxygen sensor (Polymer Optical Fiber, PreSens, Regensburg, Germany) linked to an Oxy-4 (Chanel fiber-optic oxygen-meter, PreSens, Regensburg, Germany), and oxygen concentration was recorded using the OXY-4 software version 2.30FB (https://www.presens.de/support-services/download-center/software). Before each measurement, the optodes were calibrated using nitrogen-saturated and air-saturated seawater to establish reference points for 0% and 100% oxygen saturation, respectively. Oxygen values were regressed against time to determine Pn and Rc. Gross photosynthesis (Pg) was obtained by adding the absolute value of Rc to Pn. The daily percentage contribution of photosynthesis to the holobiont’s respiratory needs (referred to as P:R in the following sections) was computed as (P/R) × 100. Here, P denotes the total daily grams of carbon per gram of ash-free dry weight (AFDW), acquired over 12 h of gross photosynthesis (Pg × 12), and R represents the daily grams of carbon respired per gram of AFDW (Rc × 24). We assumed a mole-to-mole ratio of CO2 consumed (or produced) to O2 produced (or consumed) during photosynthesis (or respiration).

Sample processing and data normalization

Samples were processed as described in26. Briefly, octocoral nubbins were freeze-dried to determine their dry weight (DW). For hexacorals nubbins, the tissue was first separated from the skeleton using an airbrush before being freeze-dried. All samples were then ground to a powder in a mortar, and a fraction was taken for AFDW determination. The remaining powder was homogenized in Milli-Q water, and three subsamples of 150 µL, 500 µL and 2.5 mL were collected for the determination of symbiont density, total chlorophyll content and protein content, respectively.

The symbiont density was assessed by haemocytometer counts (Neubauer haemocytometer, Marienfeld, Germany) under a microscope. For chlorophyll content, the subsamples were centrifuged at 8000 × g and 4 °C for 10 min, and the pellet was washed twice with MilliQ water. Subsequently, 2.5 mL of acetone (> 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) containing magnesium chloride were added to the symbiont pellet for a 24-h chlorophyll extraction process in the dark at 4 °C. After a centrifugation at 11,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the absorbance was measured at 616 nm and 663 nm using a Xenius ® spectrophotometer (SAFAS, Monaco) and the total chlorophyll concentration was determined according to Jeffrey and Humphrey62. For protein extraction, a sodium hydroxide solution (1 mol L−1) was used, and protein content was then quantified using a BC assay kit (Interchim, France)63 with protein standards prepared using bovine serum albumin (Interchim, France). The absorbance was measured at 562 nm. All physiological data were then normalized to the AFDW of the nubbin.

Field experiment

As APA was the enzyme whose activity was most sensitive to environmental changes under laboratory conditions (see results), a field experiment was conducted to test whether depth (and the associated reduction in light availability) influenced APA in corals. The study was conducted in November 2022 at the Interuniversity Institute (IUI) of Marine Sciences (Eilat, Israel), in the Red Sea. The experiment was performed on three species of octocorals (order Alcyonacea): S. glaucum, Rythisma fulvum (Forskål, 1775), and Xenia sp. (Lamarck, 1816), as well as three species of hexacorals (order Scleractinia): S. pistillata, T. reniformis, and Galaxea fascicularis (Linnaeus 1767). Throughout the following sections and figures, we will refer to Rythisma fulvum, Xenia sp. and Galaxea fascicularis as Rythisma, Xenia and Galaxea, respectively. These different species were selected because they were abundant on the reef and covered a wide range of morphologies. Coral fragments, each from different colonies, were collected by SCUBA diving in shallow waters (“shallow” condition, ca. 15 m depth) and in the upper mesophotic depths (“deep” condition, ca. 30–35 m depth; all species except Xenia sp. which was only found in shallow water), resulting in 6 coral nubbins per species and depth condition (Fig. 5). At the time of coral collection, seawater temperature was stable along the depth gradient (25.5 ± 0.5 °C). Coral nubbins were then kept in the Red Sea Simulator facility64 at the IUI, in 3 aquaria per depth condition, which were continuously supplied with non-filtered seawater. These nubbins were exposed to the natural light cycle, with light intensity adjusted to match the mean light level received at their respective in situ depth (220–250 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1 and 50–80 µmol photons−1 m−2 s−1, for shallow and mesophotic environments respectively), using shade cloth. After one-week acclimation period, coral nubbins from each condition and species (sampled in the 3 different aquaria) were individually placed in beakers containing 50 mL of FSW. The p-NPP substrate was added at a final concentration of 250 µM and the beakers were then incubated for 5 h. Immediately after the addition of the substrate and at the end of the 5-h incubation, seawater samples were taken, and enzymatic assays were then performed as described in Sect. “Enzymatic assays”. At the end of incubations, corals were frozen for later determination of the protein content as described above.

Statistical analysis and calculations

The analyses were carried out using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, version 4.3.2), and all data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Initial outlier detection relied on the Grubb test, and values were removed if the p-value was significant (p < 0.05). For the laboratory experiment, the potential effect of tank was tested for each species and condition on protein content, symbiont density, and chlorophyll content using a Kruskal–Wallis test. No significant tank effect was detected on these coral physiological parameters (Supplementary Table S1), and this random factor was therefore excluded from further analyses. Similarly, the potential tank effect on APA measurements in the Red Sea was tested and found to be non-significant (Supplementary Table S1), and thus was excluded from the analyses. The normality and homoscedasticity assumptions were checked using Shapiro’s and Levene’s tests, along with a graphical analysis of residuals. When these assumptions were met, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the effect of species and condition (either temperature or irradiance for the laboratory experiment, or the depth for the field experiment). In instances of significant differences between conditions, Tukey’s HSD test was performed. For the EEAs, as well as symbiont density and chlorophyll content, a Box-Cox transformation was performed beforehand on the whole dataset (Supplementary Material Table S2) to satisfy assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity. To test the effect of the different enzymes on EEAs in the laboratory experiment, as well as compare EEAs between mucus and coral holobiont, a paired samples ANOVA was performed, followed by pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment. Otherwise, when the assumptions were not satisfied, a Kruskal–Wallis test was used, testing the effects of condition and species independently on protein content, net and gross photosynthesis, and respiration. When the effect was significant, Dunn’s test was applied as a posteriori test. For all statistical tests, differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

For EEAs, the data from the laboratory were normalized to both the nubbin’s AFDW and the protein content. In the results, although normalization to protein content attenuates the differences between corals, normalization to AFDW was applied as it was more stable than protein content, which varied between experimental conditions in hexacorals. However, data normalized to protein content are available in Supplementary Material and are used for comparison with existing data in the literature, or for comparison with data obtained in the field for which normalization to AFDW was impossible. Moreover, for hexacorals, data normalized to surface area are available in Supplementary Material Table S3.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brandl, S. J. et al. Coral reef ecosystem functioning: eight core processes and the role of biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 17, 445–454 (2019).

Hatcher, B. G. Coral reef primary productivity: A beggar’s banquet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 106–111 (1988).

Nelson, C. E., Wegley Kelly, L. & Haas, A. F. Microbial interactions with dissolved organic matter are central to coral reef ecosystem function and resilience. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 431–460 (2023).

de Goeij, J. M., Lesser, M. P. & Pawlik, J. R. Nutrient Fluxes and Ecological Functions of Coral Reef Sponges in a Changing Ocean. In Climate Change, Ocean Acidification and Sponges. Carballo, J. L. & Bell, J. J.(eds.). 373–410. Springer International Publishing, Cham. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59008-0_8.

Knowlton, N. & Rohwer, F. Multispecies microbial mutualisms on coral reefs: The host as a habitat. Am. Nat. 162, S51–S62 (2003).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Systematic revision of symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 2570-2580.e6 (2018).

Wang, J.-T. & Douglas, A. E. Nitrogen recycling or nitrogen conservation in an alga-invertebrate symbiosis?. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 2445–2453 (1998).

Rohwer, F., Seguritan, V., Azam, F. & Knowlton, N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 243, 1–10 (2002).

Muscatine, L. Productivity of Zooxanthellae. In Primary Productivity in the Sea. Falkowski, P. G. (ed.) 381–402. Springer US, Boston, MA, (1980). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-3890-1_21.

Dubinsky, Z. & Jokiel, P. Ratio of energy and nutrient fluxes regulates symbiosis between zooxanthellae and corals. Pac. Sci. 48, 313–324 (1994).

Bednarz, V. N., Grover, R., Maguer, J.-F., Fine, M. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. The assimilation of diazotroph-derived nitrogen by scleractinian corals depends on their metabolic status. MBio 8, e02058-e2116 (2017).

Glaze, T. D., Erler, D. V. & Siljanen, H. M. P. Microbially facilitated nitrogen cycling in tropical corals. ISME J. 16, 68–77 (2022).

Godinot, C., Ferrier-Pagès, C., Sikorski, S. & Grover, R. Alkaline phosphatase activity of reef-building corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 227–234 (2013).

Fonvielle, J. A., Reynaud, S., Jacquet, S., LeBerre, B. & Ferrier-Pages, C. First evidence of an important organic matter trophic pathway between temperate corals and pelagic microbial communities. PLoS ONE 10, e0139175 (2015).

Courtial, L. et al. Effects of temperature and UVR on organic matter fluxes and the metabolic activity of Acropora muricata. Biol. Open 6, 1190–1199 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Ectohydrolytic enzyme activities of bacteria associated with Orbicella annularis coral. Coral Reefs 40, 1899–1913 (2021).

Blanckaert, A. C. A., Grover, R., Marcus, M.-I. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Nutrient starvation and nitrate pollution impairs the assimilation of dissolved organic phosphorus in coral-symbiodiniaceae symbiosis. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159944 (2023).

Yentsch, C. M., Yentsch, C. S. & Perras, J. P. Alkaline phosphatase activity in the tropical marine blue-green alga, Oscillatoria erythraea (“Trichodesmium”). Limnol. Oceanogr. 17, 772–774 (1972).

Lapointe, B. E. & O’Connell, J. Nutrient-enhanced growth of Cladophora prolifera in harrington sound, bermuda: Eutrophication of a confined, phosphorus-limited marine ecosystem. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 28, 347–360 (1989).

Annis, E. & Cook, C. Alkaline phosphatase activity in symbiotic dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae) as a biological indicator of environmental phosphate exposure. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 245, 11–20 (2002).

Girault, M. et al. Variable inter and intraspecies alkaline phosphatase activity within single cells of revived dinoflagellates. ISME J. 15, 2057–2069 (2021).

Lancelot, C. & Billen, G. Activity of heterotrophic bacteria and its coupling to primary production during the spring phytoplankton bloom in the southern bight of the north sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29, 721–730 (1984).

Chróst, R. J. et al. Photosynthetic production and exoenzymatic degradation of organic matter in the euphotic zone of a eutrophic lake. J. Plankton Res. 11, 223–242 (1989).

Fabricius, K. & Klumpp, D. Widespread mixotrophy in reef-inhabiting soft corals:the influence of depth, and colony expansion and contraction on photosynthesis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 125, 195–204 (1995).

Pupier, C. A. et al. Productivity and carbon fluxes depend on species and symbiont density in soft coral symbioses. Sci. Rep. 9, 17819 (2019).

Lange, K., Reynaud, S., De Goeij, J. M. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. The effects of dissolved organic matter supplements on the metabolism of corals under heat stress. Limnol. Oceanogr. lno. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12456 (2023).

Fabricius, K. & Alderslade, P. Soft Corals and Sea Fans: A Comprehensive Guide to the Tropical Shallow Water Genera of the Central-West Pacific the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea (Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, 2001).

Reverter, M., Helber, S. B., Rohde, S., Goeij, J. M. & Schupp, P. J. Coral reef benthic community changes in the Anthropocene: Biogeographic heterogeneity, overlooked configurations, and methodology. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1956–1971 (2022).

Norström, A., Nyström, M., Lokrantz, J. & Folke, C. Alternative states on coral reefs: Beyond coral–macroalgal phase shifts. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 376, 295–306 (2009).

Inoue, S., Kayanne, H., Yamamoto, S. & Kurihara, H. Spatial community shift from hard to soft corals in acidified water. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 683–687 (2013).

Baum, G., Januar, I., Ferse, S. C. A., Wild, C. & Kunzmann, A. Abundance and physiology of dominant soft corals linked to water quality in Jakarta Bay, Indonesia. PeerJ 4, e2625 (2016).

Sala, M., Karner, M., Arin, L. & Marrasé, C. Measurement of ectoenzyme activities as an indication of inorganic nutrient imbalance in microbial communities. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23, 301–311 (2001).

Hoppe, H. G. Significance of exoenzymatic activities in the ecology of brackish water: measurements by means of methylumbelliferyl substrates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 11, 299–308 (1983).

Blanckaert, A. C. A., Biscéré, T., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Species-specific response of corals to imbalanced ratios of inorganic nutrients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 3119 (2023).

Pupier, C. A. et al. Dissolved nitrogen acquisition in the symbioses of soft and hard corals with symbiodiniaceae: A key to understanding their different nutritional strategies?. Front. Microbiol. 12, 657759 (2021).

Pupier, C. A. et al. Divergent capacity of scleractinian and soft corals to assimilate and transfer diazotrophically derived nitrogen to the reef environment. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1860 (2019).

Hoppe, H. G., Arnosti, C. & Herndl, G. J. Ecological significance of bacterial enzymes in the marine environment. In Enzymes in the environment: activity, ecology, and applications. 73–107 (2002).

Bednarz, V., Cardini, U., Van Hoytema, N., Al-Rshaidat, M. & Wild, C. Seasonal variation in dinitrogen fixation and oxygen fluxes associated with two dominant zooxanthellate soft corals from the northern Red sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 519, 141–152 (2015).

Cardini, U. et al. Functional significance of dinitrogen fixation in sustaining coral productivity under oligotrophic conditions. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20152257 (2015).

D’Elia, C. F. The uptake and release of dissolved phosphorus by reef corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 301–315 (1977).

Crossland, C. & Barnes, D. Dissolved nutrients and organic particulates in water flowing over coral reefs at Lizard island. Mar. Freshw. Res. 34, 835 (1983).

Charpy, L. Phosphorus supply for atoll biological productivity. Coral Reefs 20, 357–360 (2001).

Canfield, D. E., Kristensen, E. & Thamdrup, B. The phosphorus cycle. In Advances in Marine Biology. 48, 419–440. Elsevier. (2005).

Rodolfo-Metalpa, R., Peirano, A., Houlbrèque, F., Abbate, M. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Effects of temperature, light and heterotrophy on the growth rate and budding of the temperate coral Cladocora caespitosa. Coral Reefs 27, 17–25 (2008).

Cziesielski, M. J., Schmidt-Roach, S. & Aranda, M. The past, present, and future of coral heat stress studies. Ecol. Evol. 9, 10055–10066 (2019).

Rädecker, N. et al. Heat stress destabilizes symbiotic nutrient cycling in corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2022653118 (2021).

Godinot, C., Houlbrèque, F., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Coral uptake of inorganic phosphorus and nitrogen negatively affected by simultaneous changes in temperature and pH. PLoS ONE 6, e25024 (2011).

Ezzat, L., Maguer, J.-F., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Limited phosphorus availability is the Achilles heel of tropical reef corals in a warming ocean. Sci. Rep. 6, 31768 (2016).

Wiedenmann, J. et al. Nutrient enrichment can increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 160–164 (2013).

Rosset, S., Wiedenmann, J., Reed, A. J. & D’Angelo, C. Phosphate deficiency promotes coral bleaching and is reflected by the ultrastructure of symbiotic dinoflagellates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 118, 180–187 (2017).

Tremblay, P., Naumann, M., Sikorski, S., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Experimental assessment of organic carbon fluxes in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata during a thermal and photo stress event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 453, 63–77 (2012).

Lyndby, N. et al. Effect of temperature and feeding on carbon budgets and O2 dynamics in Pocillopora damicornis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 652, 49–62 (2020).

Putman, R. & Wratten, S. D. Principles of Ecology (University of California Press, 1984).

Fox, M. D. et al. Differential resistance and acclimation of two coral species to chronic nutrient enrichment reflect life-history traits. Funct. Ecol. 35, 1081–1093 (2021).

Titlyanov, E. A., Titlyanova, T. V., Yamazato, K. & van Woesik, R. Photo-acclimation dynamics of the coral Stylophora pistillata to low and extremely low light. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 263, 211–225 (2001).

Hoogenboom, M. O., Campbell, D. A., Beraud, E., DeZeeuw, K. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Effects of light, food availability and temperature stress on the function of photosystem ii and photosystem I of coral symbionts. PLoS ONE 7, e30167 (2012).

Atkinson, M. J. Alkaline phosphatase activity of coral reef benthos. Coral Reefs 6, 59–62 (1987).

Mass, T. et al. Photoacclimation of Stylophora pistillata to light extremes: metabolism and calcification. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 334, 93–102 (2007).

Ezzat, L., Fine, M., Maguer, J.-F., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pages, C. Carbon and nitrogen acquisition in shallow and deep holobionts of the scleractinian coral S. pistillata. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 102 (2017).

Ziegler, M., Arif, C. & Voolstra, C. R. Symbiodiniaceae Diversity in Red Sea Coral Reefs & Coral Bleaching. In: Coral Reefs of the Red Sea. Voolstra, C. R. & Berumen, M. L. (eds.). 11, 69–89, Springer International Publishing, Cham. (2019).

Hernández, I., Niell, F. X. & Fernández, J. A. Alkaline phosphatase activity in Porphyra umbilicalis (L.) Kutzing. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 159, 1–13 (1992).

Jeffrey, S. W. & Humphrey, G. F. New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 167, 191–194 (1975).

Smith, P. K. et al. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 (1985).

Bellworthy, J. & Fine, M. The Red sea simulator: A high-precision climate change mesocosm with automated monitoring for the long-term study of coral reef organisms. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 16, 367–375 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Britt, Dror and the rest of the staff of the IUI for assistance on the field.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the Centre Scientifique de Monaco.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L. : Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. A.B. : Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MI.M.D.N. : Methodology, Investigation. R.G. : Methodology, Investigation. M.F. : Resources, Writing original draft. S.R. : Supervision, Writing original draft. C.F-P. : Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lange, K., Blanckaert, A., Marcus Do Noscimiento, MI. et al. Extracellular enzymatic activities of octocorals and scleractinian corals under environmental stress. Sci Rep 15, 43351 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27214-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27214-3