Abstract

Myxoid liposarcoma (MLPS) is a rare soft tissue sarcoma characterized by histopathological variability, which poses challenges for accurate grading and treatment planning. This study evaluated the feasibility of an automated MRI-based pipeline that combines deep learning and radiomics for non-invasive tumor assessment. In a retrospective multicenter cohort of 48 patients with histologically confirmed MLPS, a 3D U-Net convolutional neural network was trained to perform automatic tumor segmentation on axial T2-weighted MR images. Radiomics features were subsequently extracted from the segmented volumes and used to train a Random Forest classifier for predicting tumor grade, defined by centralized histopathological review according to WHO criteria. The segmentation model achieved a median Dice similarity coefficient of 0.892. The radiomics-based grading classifier reached a mean area under the curve of 0.745, with an F1-score of 0.729 and a balanced accuracy of 0.723 in distinguishing high-grade from low-grade tumors. Most classification errors occurred in borderline or histologically heterogeneous cases. These findings suggest that automated segmentation and radiomics analysis may offer valuable support for MLPS grading and complement histopathology, particularly in diagnostically complex cases. Further prospective validation in larger cohorts is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myxoid liposarcoma (MLPS) is a rare but clinically significant subtype of liposarcoma that primarily affects the deep soft tissues of the lower extremities in young to middle-aged adults1,2,3. Accurate histological grading of MLPS is essential, as the proportion of high-grade round cell components correlates with metastatic potential and guides therapeutic decision-making4.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for local staging of soft tissue sarcomas (STS). However, conventional MRI sequences provide limited specificity for non-invasive tumor grading, and interpretation often relies on subjective visual assessment5,6,7. This diagnostic ambiguity may lead to suboptimal biopsy targeting or delayed treatment planning.

Radiomics offers a promising solution by extracting quantitative image features that capture intratumoral heterogeneity beyond visual perception8,9,10,11. When combined with deep learning-based segmentation models such as 3D U-Net architectures, radiomics enables automated, reproducible image analysis pipelines12,13,14,15. Despite advances in sarcoma imaging, prior work has largely focused on heterogeneous cohorts; robust tools tailored specifically to MLPS remain scarce16.

This study aims to develop and validate a fully automated pipeline integrating MRI-based deep learning segmentation and radiomics classification to distinguish low-grade from high-grade MLPS. By addressing a clinically relevant gap, this approach may support radiologists in non-invasive tumor characterization and inform biopsy planning or surveillance strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design

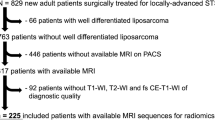

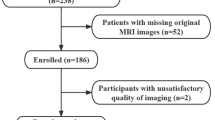

We developed a three-phase machine learning pipeline for automated segmentation and grading of MLPS on MRI. The workflow included: (1) automated tumor segmentation using a 3D U-Net–based deep learning model trained on manually annotated volumes, (2) radiomic feature extraction from the segmented regions of interest (ROIs) using standardized IBSI-compliant methods, and (3) histological grading prediction via a Random Forest classifier trained on the extracted radiomics features. A schematic overview of the pipeline is provided in Fig. 1, detailing data sources, model architecture, and training procedure.

Overview of the machine learning pipeline. A U-Net–based model was trained for automatic MLPS tumor segmentation. For Models 2–2b, the 35 in-house MRIs were augmented with 51 TCIA soft tissue sarcoma scans. PyRadiomics was used for radiomics extraction per IBSI guidelines. A Random Forest classifier then predicted tumor grade. MLPS = myxoid liposarcoma; TCIA = The Cancer Imaging Archive; STS = soft tissue sarcoma; IBSI = Imaging Biomarker Standardization Initiative.

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board (approval number: EK 1223/2024), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the anonymized, retrospective design. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Datasets

Two datasets were used to train and evaluate the segmentation models:

-

1.

In-house MLPS dataset: This included T2-weighted MRI volumes from 35 patients with confirmed MLPS by morphology as well as RNA-sequencing or FISH, acquired at the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma, Medical University of Graz. Imaging was performed on 1.5T and 3 T scanners following ESSR guidelines17. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (EK 1223/2024). Only pre-treatment, pre-operative imaging was included; cases with postoperative or post-neoadjuvant scans were excluded.

-

2.

Public TCIA STS dataset: A publicly available dataset from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), the STS collection, was used to augment training data12. It comprises 51 STS cases with diverse histological subtypes, including liposarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (formerly malignant fibrous histiocytoma), leiomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and others.

For the segmentation task, the two datasets were combined (n = 86). For tumor grading, only the in-house MLPS dataset was used to ensure histological uniformity.

In the in-house cohort, the median age was 47 years (mean: 49 ± 14 years; range: 21–79), with 19 male and 16 female patients. The thigh was the most frequent tumor site (n = 21), followed by the lower leg (n = 6). Less common sites included the gluteal region and lower arm (n = 2 each), and single cases in the axilla, chest wall, inguinal region, and pleura. Age was stratified into young adults (18–34 years, n = 5, 14.3%), middle-aged adults (35–49 years, n = 16, 45.7%), and older adults (≥ 50 years, n = 14, 40%).

In the TCIA cohort, 27 patients were female and 24 male, with a mean age of 55 years (median: 59 ± 17 years). Most were aged ≥ 50 years (n = 34, 66.7%), while middle-aged (35–49 years) and younger adults (18–34 years) accounted for 15.7% (n = 8) and 13.7% (n = 7), respectively. The most frequent histological subtype was undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (n = 17), followed by liposarcoma (n = 11), leiomyosarcoma (n = 10), synovial sarcoma (n = 5), extraskeletal bone sarcoma (n = 4), other sarcomas (n = 3), and fibrosarcoma (n = 1).

Tumor locations were predominantly in the lower extremities. The thigh was most common (left: n = 17; right: n = 11), followed by the buttocks (right: n = 5; left: n = 1), calves (right: n = 3; left: n = 2), and quadriceps (right: n = 2). Single tumors were located in the adductor, biceps, pelvis, groin, arm, hand, knee, popliteal fossa, and parascapular region.

Manual reference segmentation

Manual ground-truth segmentations were performed on all 35 in-house MLPS MRI volumes using 3D Slicer software (v5.4.0)13. Initial annotations were created by a radiology resident (JS) using the platform’s semi-automated tools, including “Grow from Seeds” and “Smoothing,” followed by manual refinements with the “Draw” and “Scissors” tools.

All segmentations were reviewed and finalized in consensus with a senior musculoskeletal radiologist (JI, 12 years of experience). The final regions of interest (ROIs) were exported in NIfTI format for subsequent radiomics analysis and machine learning pipeline development.

Automatic segmentation via machine learning

Automatic tumor segmentation was performed using the nnU-Net v2 deep learning framework, which automatically configures preprocessing steps, network architecture, and training parameters based on dataset characteristics15. Standard augmentations included intensity normalization, elastic deformation, spatial resampling, and random rotations.

Four segmentation models were trained using 5-fold cross-validation (Fig. 2):

-

Model 1: Trained on the in-house MLPS dataset only (n = 35).

-

Model 2: Trained on the pooled dataset (n = 86), combining in-house MLPS and TCIA STS cases; TCIA cases were included only in training folds.

-

Model 2a and 2b: Replicates of Model 2 using newly randomized train/test splits to assess robustness.

All test folds contained only in-house MLPS volumes to ensure evaluation specificity. Training was performed on a consumer-grade workstation running Ubuntu 22.04, using a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM). Each model was trained for 1,000 epochs per fold, requiring approximately three days to complete full cross-validation.

Segmentation performance was evaluated using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC). A DSC > 0.85 was considered indicative of strong overlap with ground-truth annotations, while values < 0.70 were considered suboptimal for clinical application.

Radiomics feature extraction

Radiomic features were extracted from each segmented tumor volume using the PyRadiomics package16, in compliance with the Imaging Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) guidelines. Each lesion yielded 1,688 features, encompassing multiple domains:

-

First-order statistics: capturing intensity distribution within the tumor.

-

Shape descriptors (2D and 3D): characterizing tumor geometry.

-

Texture features: including gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), gray-level run length matrix (GLRLM), and gray-level size zone matrix (GLSZM).

-

Filtered image features: derived from Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) and wavelet transformations to highlight spatial frequency components.

These features provided a high-dimensional representation of tumor phenotype, capturing heterogeneity and spatial complexity beyond visual interpretation. No dimensionality reduction or feature selection was performed at this stage, as the objective was to explore the full radiomic space in this pilot investigation.

Radiomics based grading classifier

Histopathological grading of all 35 in-house MLPS tumors was performed at the Diagnostic and Research Institute of Pathology following the recommendations according to the WHO classification of Soft tissue and Bone Tumours 202017. Tumors were originally classified into three categories—low grade (n = 7), intermediate grade (n = 13), and grade 3 (n = 15)—according to the pathology reports. For binary classification, low and intermediate grades were combined into a “lower-grade” group (n = 20), and grade 3 tumors were designated as “higher-grade” (n = 15). It should be noted that precise quantification of the round cell component was not consistently available in pathology records; thus, classification as “higher-grade” reflects the original pathology report and not strict application of WHO criteria (> 5% round cell component).

Radiomic features (n = 1,688 per case), extracted as described above, were matched to the corresponding histological grades to create a labeled dataset. A Random Forest classifier (Scikit-learn implementation) was trained to differentiate between high-grade and low/intermediate-grade tumors18.

The input features were standardized using Z-score normalization (StandardScaler), applied separately to training and test data within each fold to prevent data leakage. No feature selection or dimensionality reduction was performed to preserve the complete feature space for exploratory analysis.

To address variability due to the small sample size, model performance was evaluated using 10× repeated, stratified 3-fold cross-validation, resulting in 30 independent model runs. Default hyperparameters were used to avoid overfitting and provide a reproducible baseline.

A visual overview of the training, validation, and evaluation setup is provided in Fig. 3.

Performance metrics, averaged across all 30 models, included sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, balanced accuracy, and the weighted F1 score to account for class imbalance. To ensure balanced decision-making between false positives and false negatives, a fixed probability cutoff of 0.5 was applied for all diagnostic measures. In addition, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC) was reported as a cutoff-independent indicator of overall diagnostic performance.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz (No. 31–236 ex 18/19).

Consent to participate

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the anonymized, retrospective design.

Results

Automated segmentation performance

Model 1, trained exclusively on the in-house MLPS dataset (n = 35), achieved a mean Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of 0.722 (SD: 0.367). In comparison, Model 2—trained on the combined in-house and TCIA STS datasets (n = 86)—achieved a significantly higher average DSC of 0.883, representing a 16.1% absolute improvement in segmentation accuracy.

To assess robustness, Models 2a and 2b replicated Model 2 using independently randomized train/test splits. Their performance remained consistent (mean DSCs: 0.887 and 0.892, respectively), with minimal variance across runs (pooled SD: 0.0037), confirming reproducibility of the segmentation pipeline.

The best-performing model (Model 2b) achieved a DSC of 0.892, demonstrating excellent agreement with expert-defined tumor contours. A fold-wise breakdown is provided in Table 1.

Two segmentation outliers contributed to localized performance dips—one small-volume lesion and one pleural tumor with atypical morphology—where sub-models failed to identify any voxels, resulting in a DSC of 0.0. These rare cases had a disproportionate impact on average fold scores. Notably, other atypical cases, such as an axillary MLPS, were segmented correctly, suggesting generalizability to uncommon localizations. A representative MRI case is shown in Fig. 4, illustrating typical imaging features of MLPS and the accuracy of the manual segmentation mask used for training and model evaluation.

Representative MR images of a 52-year-old man with MLPS in the thigh. (a, b) STIR images show a well-demarcated hyperintense mass with internal septations (yellow arrows). (c) T1-weighted coronal image shows iso-/hyperintensity. (d) Fat-suppressed contrast T1w image reveals heterogeneous enhancement (white arrows). (e) Manual segmentation overlay (red) aligns with tumor margins (star). STIR = short tau inversion recovery; T1w = T1-weighted; FS = fat-suppressed.

Radiomics-based tumor grading

As shown in Table 2, the Random Forest classifier trained to differentiate high-grade from lower-grade MLPS achieved a mean ROC AUC of 0.745 ± 0.144 and a mean F1 score of 0.729 ± 0.129 across 30 stratified 3-fold cross-validation runs.

While some iterations achieved high sensitivity and specificity, these fluctuations were not consistently reproducible and likely reflect random variation in small-sample splits. However, repeated cross-validation mitigated overfitting and enabled robust performance estimation.

Figure 5 illustrates the variability in ROC AUC and F1 scores across all model runs. Figure 6 shows the distribution of F1 scores, emphasizing inter-run variance and underscoring the challenges of classification in limited-cohort rare sarcoma datasets.

Discussion

This study presents a fully automated deep learning and radiomics pipeline for MRI-based analysis of myxoid liposarcoma (MLPS), a rare soft tissue sarcoma with highly variable imaging characteristics. While AI-driven image analysis is increasingly applied to common malignancies, its utility in rare tumors like MLPS remains underexplored19,20. Our findings demonstrate that robust segmentation and grading of MLPS is feasible using a relatively small but well-curated dataset.

We addressed the challenge of limited training data by augmenting institutional MLPS cases with public TCIA sarcoma data21,22. This strategy substantially improved segmentation performance—achieving a Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of 0.892—and reduced variability across folds. This improvement underscores the importance of dataset diversity in training segmentation models, particularly for rare tumors with heterogeneous presentations5,7.

However, segmentation performance declined in cases involving anatomically atypical or small-volume tumors, including lesions in the pleura and axilla. These outlier cases highlight the model’s sensitivity to underrepresented spatial contexts and reinforce the need for broader anatomical representation during training23.

The second component of our pipeline—radiomics-based tumor grading—demonstrated moderate classification performance, with a mean area under the ROC curve of 0.745 and a mean F1 score of 0.729. These results support the feasibility of using quantitative imaging biomarkers to assist in the non-invasive stratification of MLPS24,25. The primary clinical relevance of radiomics in this context lies in differentiating low/intermediate-grade from high-grade MLPS, as this distinction may influence treatment decisions such as the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. To reflect this, we report the sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and positive predictive value (PPV) of the radiomics models, where a relatively strong sensitivity of 0.820 is shown on average across all trained models. In particular, the NPV is informative for assessing the model’s potential to overlook high-grade tumors, which is an important consideration when identifying patients in whom neoadjuvant chemotherapy is unlikely to be indicated. Although the achieved NPV of 0.744 is only moderately strong in the pilot study, we would expect it to improve with a larger training dataset; a higher NPV would increase confidence that patients predicted as low/intermediate grade truly lack high grade disease.

Our radiomics feature set, comprising 1,688 IBSI-compliant descriptors, was used in its entirety without feature selection or dimensionality reduction. While this approach maximized exploratory breadth, future studies could benefit from feature pruning to enhance model interpretability and mitigate overfitting risk26. Prior work has shown that interobserver variability in sarcoma grading remains substantial27,28,29, and quantitative image analysis may help standardize assessments30.

Importantly, our study provides a realistic and reproducible example of applying AI to a rare sarcoma subtype. Unlike large-scale oncology studies with inflated performance metrics, our results reflect practical challenges and achievable benchmarks in data-constrained environments31,32. This reinforces the premise that clinically meaningful AI models can be developed even with limited sample sizes, provided that study design, validation, and transparency are rigorously maintained.

Looking forward, future directions include expanding multi-center datasets, incorporating uncertainty quantification, and exploring transformer-based architectures for improved segmentation. Additionally, identifying the most discriminative radiomic features for tumor grade may support explainability and facilitate integration into clinical workflows33.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the in-house MLPS dataset was small (n = 35), which constrains the generalizability of both the segmentation and grading models. Although additional STS cases from TCIA were used to enhance segmentation robustness, the grading classifier was trained solely on the in-house MLPS cohort, increasing the risk of overfitting. Second, the extraction of over 1,600 radiomic features per tumor volume without feature selection or dimensionality reduction may have introduced redundancy and limited interpretability. Third, segmentation performance declined in cases with atypical tumor location or very small lesion size, underscoring the need for more anatomically diverse datasets. Fourth, the absence of uncertainty quantification limits the clinical applicability of our models and highlights the need for confidence-aware AI systems. Finally, histologic grading labels were derived from original pathology reports rather than strict WHO criteria (> 5% round cell component), as precise quantification of the round cell content was inconsistently documented. While this approach may have introduced classification variability and limits generalizability, it reflects real-world reporting practices in routine clinical settings.

Conclusion

This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility of a fully automated deep learning and radiomics pipeline for MRI-based assessment of MLPS—a rare and diagnostically challenging sarcoma. By integrating publicly available STS data with a curated institutional MLPS cohort, we achieved high segmentation performance (DSC up to 0.892) and promising results in radiomics-based tumor grading (ROC AUC 0.745). The proposed pipeline illustrates how AI can be tailored for rare cancers, offering a reproducible and clinically relevant approach that bridges imaging, pathology, and machine learning. As multi-center collaborations and data-sharing initiatives expand, future refinements—such as incorporating larger cohorts, predictive uncertainty estimation, and interpretable feature selection—will be essential to support clinical decision-making and advance non-invasive tumor characterization in sarcoma care.

Data availability

The publicly available TCIA dataset used in this study can be accessed at [https://doi.org/10.7937/K9/TCIA.2015.7GO2GSKS](https:/doi.org/10.7937/K9/TCIA.2015.7GO2GSKS). The in-house dataset cannot be shared publicly due to patient confidentiality and institutional data protection policies but may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author and with appropriate ethical approvals. Raw performance results as well as the derived performance metrics of the tumor classification models are available under the following URL: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17414578](https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17414578).

Abbreviations

- MLPS:

-

Myxoid liposarcoma

- TCIA:

-

The Cancer Imaging Archive

- STS:

-

Soft tissue sarcoma

- DSC:

-

Dice Similarity Coefficient

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th Edition, Volume 3. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; (2020).

Ho, T. P. Myxoid liposarcoma: how to stage and follow. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 24 (4), 292–299 (2023).

Loubignac, F., Bourtoul, C. & Chapel, F. Myxoid liposarcoma: a rare soft-tissue tumor with a misleading benign appearance. World J. Surg. Oncol. 7, 42 (2009).

Billingsley, K. G. et al. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of diseases and postmetastasis survival. Ann. Surg. 229 (5), 602–610 (1999).

Encinas Tobajas VM et al. Myxoid liposarcoma: MRI features with histological correlation. Radiologia 65 (Suppl 2), S23–32 (2023).

Kamalapathy, P. N. et al. Development of machine learning model algorithm for prediction of 5-year soft tissue myxoid liposarcoma survival. J. Surg. Oncol. 123 (7), 1610–1617 (2021).

Mujtaba, B. et al. Myxoid liposarcoma with skeletal metastases: pathophysiology and imaging characteristics. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 50 (1), 66–73 (2021).

Crombé, A. et al. Radiomics and artificial intelligence for soft-tissue sarcomas: current status and perspectives. Diagn. Interv Imaging. 104 (12), 567–583 (2023).

Tfayli, Y., Baydoun, A., Naja, A. S. & Saghieh, S. Management of myxoid liposarcoma of the extremity. Oncol. Lett. 22 (2), 596 (2021).

Crombé, A. et al. Can radiomics improve the prediction of metastatic relapse of myxoid/round cell liposarcomas? Eur. Radiol. 30 (5), 2413–2424 (2020).

Meglič, J., Sunoqrot, M. R. S., Frost Bathen, T. & Elschot, M. Label-set impact on deep learning-based prostate segmentation on MRI. Insights Imaging. 14 (1), 157 (2023).

Vallières, M., Freeman, C. R., Skamene, S. R. & El Naqa, I. Soft-Tissue-Sarcoma (STS) [dataset]. The Cancer Imaging Archive; (2015). Available from: https://doi.org/10.7937/K9/TCIA.2015.7GO2GSKS

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30 (9), 1323–1341 (2012).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods. 18 (2), 203–211 (2021).

van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational radiomics system to Decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77 (21), e104–e107 (2017).

Noebauer-Huhmann, I. M. et al. Soft tissue tumor imaging in adults: European society of musculoskeletal Radiology–Guidelines 2024: imaging immediately after neoadjuvant therapy in soft tissue sarcoma, soft tissue tumor surveillance, and the role of interventional radiology. Eur. Radiol. 35, 3324–3335 (2025).

Pedregosa et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Khalil, S. et al. Enhancing ductal carcinoma classification using transfer learning with 3D U-net models in breast cancer imaging. Appl. Sci. 13 (7), 4255 (2023).

Yang, J., Wu, B., Li, L., Cao, P. & Zaiane, O. MSDS-UNet: a multi-scale deeply supervised 3D U-Net for automatic segmentation of lung tumor in CT. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 92, 101957 (2021).

Vallières, M. et al. Radiomics strategies for risk assessment of tumour failure in head-and-neck cancer. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 10117 (2017).

Safonova, A. et al. Ten deep learning techniques to address small data problems with remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 125, 103569 (2023).

Isler, I. S., Mohaisen, D., Lisle, C., Turgut, D. & Bagci, U. Uncertainty-guided coarse-to-fine tumor segmentation with anatomy-aware post-processing. ArXiv ;ArXiv:250412215. (2025).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45 (1), 5–32 (2001).

Varoquaux, G. Cross-validation failure: small sample sizes lead to large error bars. Neuroimage 180, 68–77 (2018).

Aerts, H. J. W. L. et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 5 (1), 4006 (2014).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Validity and reproducibility of histologic diagnosis and grading for adult soft-tissue sarcomas. Hum. Pathol. 33 (1), 111–115 (2002).

Kilpatrick, S. E. Problems in grading soft tissue sarcomas. Pathol. Patterns Rev. 114 (suppl_1), S82–S88 (2002).

Coindre, J. M. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: the challenge of providing precise information in an imprecise world. Histopathology 48 (1), 42–50 (2006).

Lambin, P. et al. Radiomics: the Bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14 (12), 749–762 (2017).

Oakden-Rayner, L. The replication crisis in radiology: another call to action. Radiology 296 (2), E30–E34 (2020).

Monkam, P. et al. Detection and classification of pulmonary nodules using convolutional neural networks: a survey. IEEE Access. 7, 78075–78091 (2019).

Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A. & Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty Estimation using deep ensembles. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) for providing public access to the soft tissue sarcoma dataset. DeepL Write was used to assist with language editing and to improve manuscript clarity.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study. The work was supported by internal departmental resources at the Department of Radiology, Medical University of Graz, Austria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S., J.I., M.B., and M.U.: Conceptualization, supervision, writing, original draft. J.I., J.S., and M.B.: Formal analysis, methodology, software, data curation, validation. M.B. and M.U.: Radiomics feature extraction, validation. M.U., B.L.A., M.F., and A.L.: Investigation, clinical resources. All authors: Writing—review and editing, and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steiner, J., Bloice, M., Igrec, J. et al. MRI-based deep learning and radiomics pipeline for myxoid liposarcoma: a feasibility study in a rare sarcoma. Sci Rep 15, 44104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27217-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27217-0