Abstract

The main objective of osteoporosis management is to prevent osteoporotic fractures. Using machine learning methods, new risk variables can be identified to enhance the ability to identify women with osteoporosis who are at an increased risk of bone fracture. A multicenter study using machine learning-based methods was conducted in two independent cohorts of postmenopausal women (HURH and Camargo Cohorts), with clinical follow-up periods ranging from 8 to 10 years. The prediction models were developed in the HURH Cohort and validated using the Camargo Cohort, an independent external group of postmenopausal women. This study developed machine learning models to predict the risk of osteoporotic bone fractures. One is for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, and the other is for general postmenopausal women. For each of these, two variable grouping options were used. The aggregation with the most predictive power included variables that are generally most accessible in medical practice. For postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, the AUC was 0.92, and for general postmenopausal women, it was 0.88. The results highlighted the significance of the previous fracture, DXA data, vitamin D levels, and PTH levels in predicting future fractures. Machine learning should be used to identify postmenopausal women at increased risk of fractures. This study summarizes that previous fractures, DXA, PTH, and vitamin D play crucial roles in identifying these women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is the most common bone disorder worldwide, characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD), reduced bone mass, alterations in bone microarchitecture, and an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis is a silent, progressive disease with dramatic clinical and economic consequences. It has been reported that one in three postmenopausal women has osteoporosis, and the majority will have a bone fracture at some point in life. Osteoporotic bone fractures are associated with increased morbidity, disability, and mortality, and a worse quality of life1,2,3,4.

Preventing the appearance of osteoporotic bone fractures is the principal therapeutic objective in the management of osteoporosis5. Therefore, it is crucial to identify patients at higher risk of suffering fractures to prevent their occurrence. In this sense, various algorithms have been developed to identify patients with a higher risk of suffering the disease and/or suffering bone fractures6. The most widely used is FRAX, which provides risk stratification by combining various risk factors. The procedure used to perform it was the statistical analysis of cohorts of patients with osteoporotic fractures using previously identified risk factors7. These algorithms demonstrate strong discriminative ability but require adjustments to enhance their predictive performance8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However, FRAX is intended to identify patients for treatment7,15. Although FRAX should not be used to assess the reduction in fracture risk in individuals in treatment, it may still have value for guiding the need for continued treatment or treatment withdrawal. Using machine learning methods16, new variables associated with bone fracture risk could be identified to improve the ability to single out osteoporotic women at increased risk of bone fracture.

The central premise of machine learning is to present algorithms that input data, apply computational analysis to predict output values within satisfactory accuracy ranges, recognize patterns and trends, and, finally, learn from previous experience17. Machine learning works with complex distributions to determine probabilistic associations and find the minimum number of features that capture the essential patterns in the data to develop a predictive model18. Machine learning methods have shown better results than traditional statistical model-based methods17. Thus, machine learning is applied to identify risk factors and classify multiple pathologies. Some of the techniques developed for classification systems and data processing are Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB), k-nearest Neighbors (KNN), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), or decision tree (DT)19.

In this scenario, the primary objective was to identify variables associated with an increased risk of bone fracture in postmenopausal women, thereby enhancing the ability to recognize subjects with a higher risk of fracture by developing a risk prediction algorithm. Machine learning-based methods were used in two independent cohorts of postmenopausal women with prolonged clinical follow-up.

Results

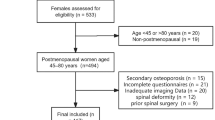

The study comprised 576 postmenopausal women, divided into two independent cohorts: the HURH and Camargo cohorts. Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the study cohorts. The HURH Cohort included 276 postmenopausal women diagnosed with osteoporosis. After a clinical follow-up, 72 patients suffered osteoporotic bone fractures. The Camargo cohort involved 300 postmenopausal women from the general population, and after the clinical follow-up, 91 suffered a fracture.

Table 2 presents the different machine learning methods tested for predicting osteoporotic fractures after 8–10 years of clinical follow-up in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (HURH Cohort). Additionally, the table includes data from external validation using records from a general population of postmenopausal women without an osteoporosis diagnosis (Camargo Cohort). Two predictive models were developed based on two sets of variables: one including all variables (set 1) and another limited to variables more readily available in general medical consultations (set 2). In both cases, the machine learning method yielding the best performance for predicting osteoporotic fractures was XGB (Table 2). The XGB method achieved the highest values across the evaluated metrics, including balanced accuracy, recall, precision, area under the curve (AUC), F1 score, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), degenerated Youden index (DYI), and kappa. For the HURH Cohort, the AUC was 0.88 for variables in set 1 and 0.92 for those in set 2. In the external validation using the Camargo Cohort, the AUC was 0.88 for both sets of variables.

For osteoporotic postmenopausal women (HURH Cohort), the results showed that the most influential variable in the osteoporotic bone fracture was a previous fracture, followed by parathormone (PTH) and lumbar spine T Score (Figs. 1 and 2). If the risk analysis includes all study variables, the results showed that cortical vBMD was the fourth most influential variable for osteoporotic fracture risk. Figure 1A shows the level of influence of each variable. The ROC curve was calculated, and the results showed that the system based on the XGB model obtains a larger area, allowing a greater accuracy in predicting osteoporotic bone fracture (Fig. 1B), the AUC was 0.88. The radar plots indicated that the model training subsets yielded similar scores to those in the test subsets. The XGB was the system with the larger area (Fig. 1C). The order of influence on fracture risk of the most accessible variables (variables included in set 2) is summarized in Fig. 2A. The most influential variables for osteoporotic fracture were previous fracture, PTH, lumbar spine T score, and vitamin D levels. The XGB method showed the largest area in the ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2B). The AUC was 0.92. The radar plots of training and test subsets are summarized in Fig. 2C. In the case of the general population of postmenopausal women (Camargo Cohort), which served as the external validation for the proposed machine learning model, the highest area under the ROC curve (AUC) was achieved using the XGB model (Fig. 3A), with an AUC of 0.88. When the risk analysis was limited to the most accessible variables (set 2), the XGB method also demonstrated the most significant area under the ROC curve (Fig. 3B), with an AUC of 0.88. In both scenarios, radar charts illustrated that the test subsets of the model were consistent with the performance scores, further emphasizing that XGB consistently achieved the highest AUC (Figs. 3C and D). These results underscore the robustness of the XGB model in external validation, particularly in its ability to generalize across diverse clinical contexts.

Analysis of clinical variables included in set 1 in the HURH cohort. Order of influence of clinical variables on the osteoporotic fracture prediction (A). ROC curves for the assessed machine learning methods (B). Radar plot in the training phase and the test phase (C). PTH: Parathyroid hormone, vBMD: volumetric bone mineral density, TBS: trabecular bone score, DMII: diabetes mellitus II, BMI: body mass index, SVM: Support Vector Machine, DT: Decision Trees, GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, XGB: Extreme Gradient Boosting.

Analysis of clinical variables included in set 2 in the HURH cohort. Order of influence of clinical variables on the osteoporotic fracture prediction (A). ROC curves for the assessed machine learning methods (B). Radar plot in the training phase and the test phase (C). PTH: Parathyroid hormone, vBMD: volumetric bone mineral density, TBS: trabecular bone score, DMII: diabetes mellitus II, BMI: body mass index, SVM: Support Vector Machine, DT: Decision Trees, GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, XGB: Extreme Gradient Boosting.

External validation of the results with the Camargo cohort. ROC curves for the assessed machine learning methods, with the clinical variables included in sets 1 (A) and 2 (B). Radar plot in the validation phase for the clinical variables included in sets 1 (C) and 2 (D). SVM: Support Vector Machine, DT: Decision Trees, GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, XGB: Extreme Gradient Boosting.

Discussion

Artificial intelligence, with its different tools such as machine learning, allows the construction of models to identify the risk of patients and subsequently validate them in the same population that has permitted their development; these models would make it possible to validate the new diagnostic instruments available to us and determine whether they provide greater prognostic power. This study designed different models using a machine learning methodology, incorporating various parameters, including some typically not utilized in clinical practice, such as trabecular bone score (TBS) and 3D-DXA. A model was also performed using parameters available in all hospital centers. The models were tested in two independent subject cohorts, one compromised by osteoporotic postmenopausal women and the other by general postmenopausal women.

In osteoporotic postmenopausal women, the two models obtained have an AUC greater than 0.80, indicating the models’ great power in identifying osteoporotic postmenopausal women with an increased fracture risk. The more complex model additionally incorporated volumetric cortical BMD, history of previous falls, and TBS. The addition of a greater number of parameters, both clinical and densitometric, did not improve the diagnostic capacity of the model. In general, postmenopausal women (without osteoporosis diagnosis), the models developed have great power for the identification of postmenopausal women with an increased risk of bone fractures. The AUC was 0.88 for two sets of variables. For the prediction of bone fracture in postmenopausal women without a diagnosis of osteoporosis, adding a larger number of parameters also did not improve predictive ability. In both cohorts, the models for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women were based on the XGB method. That algorithm exhibits some crucial characteristics. The method is efficient in terms of speed and scalability. XGB is highly flexible and can handle various data types, including numerical, categorical, and missing data. Its ability to capture non-linear and complex relationships in the data makes it a powerful tool for predictive modeling. Additionally, XGB is known for its ability to handle data imbalances and its resistance to overfitting, resulting in more robust and accurate models20.

The results showed that the presence of a previous fracture was the most significant factor in the artificial intelligence models for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. It had been reported that the risk of osteoporotic fracture increases predominantly in the 2 years following the fracture, giving rise to the concept of imminent risk of fracture21. It has also been summarized that the fracture risk then decreases but is still higher than in patients who have not suffered a previous fracture22,23,24,25. PTH has a significant influence on our prediction models. This is an exciting result because PTH levels are not considered in the most commonly used algorithms for predicting osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. PTH is crucial in bone metabolism. It binds to the PTH receptor located on osteoblasts, causing the release of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa beta ligand (RANKL), which facilitates the proliferation and maturation of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone resorption26. More importance has usually been given to vitamin D as it exerts a double effect: on the one hand, it inhibits the release of PTH, and on the other hand, it facilitates bone mineralization27. However, the relationship between PTH and vitamin D occurs with 25-hydroxycholecalciferol values below 32 ng/mL. The direct relationship is lost with higher values, and PTH can be deleterious to bone28. Our results also confirm the importance of vitamin D in the risk of osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women. It was important in our prediction models for osteoporotic women and the general population. BMD has been widely used for disease diagnosis, indication, and therapeutic response29. Our results indicated that measuring BMD in the spine, femoral neck, and total hip is vital in the simplified prediction models, incorporating the most accessible variables in general medical practice. BMD is a technique with high specificity and low sensitivity, and a significant percentage of fractures occur in individuals with osteopenia or normal BMD, as indicated by the NORA study30. Moreover, Bouxsein et al. found that improvements in BMD were closely related to a greater reduction in vertebral and hip fractures31. However, BMD cannot modify the increased risk determined by a previous fracture.

The more complex prediction models introduce TBS and 3D-DXA as predictive variables. TBS is a textural analysis resulting from a computed evaluation of pixel gray-level variations in previously obtained LS DXA images. It correlates with 3D parameters of bone microarchitecture, such as trabecular connectivity, the number of trabeculae, and their separation32. A decrease in TBS is associated with an increased risk of fracture33. 3D-DXA allows the evaluation of the shape and intrinsic properties of the material that determine bone strength. It provides a 3D analysis of the cortical and trabecular compartments34. Decreased BMD is associated with an increased risk of fractures. However, it does not provide information on volumetric density distribution, while DEXA-3D offers information on bone strength. In the elderly, cortical thinning, periosteal apposition, and endocortical resorption are observed. Normal BMD does not show these changes. QCT is available to explore the three-dimensional structure of bones. However, it is an expensive technique and involves a high dose of radiation for the patient. aBMD is associated with an AUC curve of 0.712, with an OR of 2.48 (1.595–3881) for predicting the risk of hip fracture. These data are similar to those obtained with 3-DXA and do not provide superiority35. Our machine learning models, excluding DEXA-3D, enhance this prediction capability. TBS and 3D-DXA play a role in prediction models that include additional variables. However, they did not improve the prediction capacity of our simpler models, which use more common parameters in clinical practice. This is probably because these are bone quality parameters already quantified in the previous fracture. The main limitation of our study is that the size of both cohorts did not permit a more detailed analysis, such as examining the various types and locations of fractures.

Another limitation is that our analysis treated fracture occurrence as a binary outcome at the end of follow-up, without considering the exact timing of fracture events. Therefore, the models do not capture the temporal dynamics of fracture risk, including the concept of imminent risk, which is known to be particularly high within the first two years after a fracture. Incorporating time-to-event analyses, such as the Cox proportional hazards model or survival-based machine learning approaches, in future studies could provide a more nuanced understanding of both short- and long-term fracture risk trajectories. It is also important to note that the algorithm included postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who were undergoing various treatments. This was to create an algorithm that accurately reflected actual clinical practice. Another limitation is that both cohorts were recruited in Spain. Therefore, the predictive models developed here reflect the characteristics of Spanish postmenopausal women and may not fully generalize to populations with different ethnic backgrounds, genetic profiles, environmental exposures, or healthcare systems. External validation in cohorts from other countries and more diverse populations will be essential to confirm the robustness and clinical applicability of our models before widespread adoption. Nonetheless, this study will provide a foundation for future research to incorporate a broader range of postmenopausal women and to create more precise and practical algorithms for predicting fracture risk.

Although the total sample size of this study (n = 576; 276 participants in the HURH Cohort and 300 participants in the Camargo Cohort) might be considered modest when compared with very large datasets, it is appropriate for the development and validation of machine learning models in clinical research, especially considering the number of outcome events and the ratio between predictors and observations. Recent methodological studies emphasize that the adequacy of sample size in machine learning-based prediction models depends on several factors beyond the absolute number of observations, including the number of events per predictor, the expected signal-to-noise ratio, and the model’s anticipated performance, rather than on arbitrary numerical thresholds. In our study, the number of fracture events (72 in the HURH Cohort and 91 in the Camargo Cohort) provides a reasonable events-per-variable ratio, which is considered crucial to reduce overfitting and ensure stable estimates. Furthermore, the sample size used here is similar or even larger than those in several previously published ML studies in osteoporosis and other medical domains. To further minimize the risk of overfitting, we implemented several well-established methodological strategies. These included a nested cross-validation framework, Bayesian hyperparameter optimization with explicit regularization, constraints on model complexity, and systematic feature selection to retain only the most relevant predictors. Such approaches are widely recognized as effective for reducing variance and improving generalizability in predictive modeling. Moreover, bootstrap-based resampling was used to estimate performance uncertainty and assess model stability. Crucially, the models were tested not only with internal resampling techniques but also with an independent external cohort (the Camargo Cohort). External validation is considered the gold standard to evaluate model generalizability and to detect potential overfitting. The comparable performance metrics observed between the training/test sets and the external validation cohort (AUC 0.88–0.92) support the robustness and reproducibility of our findings, indicating that the models are capturing real clinical patterns rather than noise.

In conclusion, this study developed two machine learning models to predict the risk of osteoporotic bone fractures in postmenopausal women, both exhibiting high predictive power (AUC = 0.92 and 0.88). These models demonstrated improved predictive capability when incorporating variables that are more accessible in clinical practice, particularly previous fractures, DXA data, PTH, and vitamin D levels. This study emphasizes that machine learning methodology should be applied to identify postmenopausal women with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A longitudinal or prospective study was conducted in two independent cohorts of postmenopausal women: the HURH Cohort and the Camargo Cohort. The HURH Cohort (n = 276) included postmenopausal women who were diagnosed with osteoporosis. The inclusion criteria were postmenopausal women (no menstruation for more than 12 months) and a low bone mass or osteoporosis, as defined by Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). We randomly included women from the Densitometry Unit at Rio Hortega University Hospital (Valladolid, Spain) who were sent consecutively. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation’s Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis6, patients had been diagnosed with osteoporosis by clinical criteria. Subsequent follow-up was conducted by the Bone Metabolism Unit or primary care physicians. The medical history and the different episodes were recorded in the electronic medical record and could be followed up. The Camargo Cohort (n = 300) comprised a general population of postmenopausal women from Santander, Spain. The Camargo Cohort Study is a community-based study designed to evaluate the prevalence and incidence of metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism, as well as osteoporotic fractures and risk factors for osteoporosis and fragility fractures, in postmenopausal women attending a primary care center in Northern Spain (Santander)36. The women were selected based on demographic data from the HURH cohort. Subsequent follow-up was conducted by the Bone Metabolism Unit at University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria, or by primary care physicians. The Camargo Cohort was used to perform an external validation of the results obtained in the HURH cohort. All subjects were recruited from 01/01/2007 to 01/01/2009, with a follow-up period of 8 to 10 years. Data were accessed for research purposes from 01/01/2007.

Clinical, demographic, and analytical data such as age at diagnosis, family history, lifestyle factors, previous illnesses, and past and present medication were collected from each subject.

Most postmenopausal women received treatment during the study; some also had prior therapy before starting the study. They were all analyzed together to ensure the findings accurately reflect real-world clinical observations. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated. DXA data were also collected. The trabecular bone score (TBS) was evaluated at the lumbar level (L1-L4) using TBSiNsight 2.1 (Med-Imaps, Merignac, France). In addition, three-dimensional Dual-Energy X-ray absorptiometry (3D-DXA) was determined for each patient. A DXA scan was performed using a Prodigy scanner (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The software 3D-SHAPER (version 2.6, Galgo Medical S.L., Barcelona, Spain) was also used. This method utilized a statistical 3D model of the proximal femur’s form and density, built from a quantitative computed tomography (QCT) database comprising Caucasian men and women. The modeling details of this method can be found in Winzenrieth et al. and Humbert et al. 36,38. The study was conducted using DXA exploration to obtain a 3D model specific to each patient’s proximal femur, generating measurements in 3D from the total area of interest in the femur. The volumetric BMD (vBMD, mg/cm3), bone mineral content (BMC) (g), and volume (cm3) were calculated in the trabecular, cortical, and integral (trabecular and cortical) compartments, respectively. The volumetric BMD (vBMD, mg/cm3), bone mineral content (BMC) (g), and volume (cm3) were calculated in the trabecular, cortical, and integral (trabecular and cortical) compartments, respectively. The cortical thickness (Cth, mm) and BMD of the cortical surface (sBMD cortical, mg/cm2, obtained by the multiplication of cortical vBMD (mg/cm3) and Cth (cm)) provided additional analysis for the cortical region. The precision of the models and 3D-SHAPER measurements was evaluated against a QCT35,37. The average form precision—i.e., the average distance between external limits of the femur geometry—was derived from 3D-SHAPER and QCT, and the result was 0.93 mm. Regarding bone density and cortical bone thickness, the correlation coefficients between 3D-SHAPER and the measurements derived from QCT were 0.86, 0.93, and 0.91 for trabecular vBMD, cortical vBMD, and cortical thickness, respectively35,37.

The study participants were followed up clinically for 8–10 years, after which they were evaluated for osteoporotic fractures. The diagnosis of vertebral fractures was made based on lateral radiographs of the dorsal and lumbar spine taken throughout the follow-up and reviewed by the same physician (FCS), who determined them according to the Genant criteria38. Non-vertebral fractures were obtained from their medical records. Osteoporotic bone fractures were determined after a follow-up of 8–10 years.

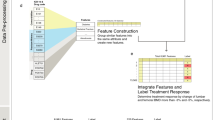

Machine learning analysis

The XGB method was proposed as the primary method for data analysis due to its scalability, rapid execution, and commendable accuracy. Moreover, its versatility enables parallel computing39. Various other machine learning methods documented in the scientific literature were employed to evaluate the efficacy and performance of this system. The most important were the SVM40, DT 41, GNB42, and KNN43. Models resulting from these methodologies were developed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA; MATLAB R2023)44. The procedural steps undertaken to implement the machine learning algorithms are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1. This study combined nested cross-validation with Bayesian optimization techniques to robustly and efficiently tune the hyperparameters of machine learning models. Within the nested cross-validation framework, the outer loop evaluated the model’s generalized performance, while the inner loop focused on hyperparameter optimization. In the inner loop, Bayesian optimization was employed as a strategy to efficiently explore the space of key hyperparameters, including maximum tree depth (max_depth), the number of estimators (n_estimators), the learning rate (learning_rate), and regularization terms (lambda and alpha). Using a probabilistic model based on a Gaussian process, Bayesian optimization identified optimal hyperparameter combinations by leveraging information from previous iterations, thereby minimizing the need for exhaustive evaluations and focusing on the most promising regions45,46. This approach reduced the risk of overfitting by ensuring that test data in the outer loop remained entirely independent of the optimization process and improved model stability by conducting consistent evaluations across multiple data partitions. The combination of these techniques yielded models with optimized performance and high generalizability. In addition, the specific hyperparameters considered for each algorithm were as follows: for XGB, max_depth (2–10), n_estimators (50–500), learning_rate (0.01–0.3), subsample (0.5–1.0), colsample_bytree (0.5–1.0), and regularization parameters lambda (0–10) and alpha (0–10); for SVM, C (0.01–100), gamma (1e-5–1), and kernel type (linear, polynomial, radial basis function); for DT, max_depth (1–20), min_samples_split (2–20), and min_samples_leaf (1–10); for GNB, the var_smoothing parameter (1e-12–1e-6); and for KNN, n_neighbors (1–30), weights (uniform, distance), and metric (Euclidean, Manhattan). Bayesian optimization with a Gaussian process surrogate model was applied within a 5-fold cross-validation framework to explore the hyperparameter space efficiently. The configuration that maximized mean balanced accuracy in the cross-validation folds was selected, then retrained on the entire training set, and finally evaluated on the independent test set. This process was repeated across 100 simulation iterations to ensure robustness. Building on a systematic feature relevance analysis, we employed a combined approach to identify the most influential variables. Initially, feature importance was evaluated using a preliminary XGB model, which provided scores derived from gain, coverage, or weight. This was followed by iterative feature selection techniques such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), with XGB as the base estimator, to reduce the feature set while maintaining high predictive performance. Lastly, the impact of removing specific features was assessed through cross-validation, ensuring that only those significantly contributing to the model’s performance were retained.

To further prevent overfitting in XGB, additional techniques were employed, including explicit regularization via the parameters lambda and alpha, controlling the maximum tree size (max_depth), adjusting the learning rate (learning_rate) to a lower value, and applying early stopping to halt training if validation metrics failed to improve after several consecutive iterations. Bootstrap validation was also performed, generating multiple data subsets through resampling to estimate uncertainty in performance metrics and ensure consistency. Additionally, the model was validated on an independent external cohort to assess its generalizability across diverse clinical contexts. The data were randomly split into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets to ensure a balanced representation of key classes and characteristics. The simulations were rigorously executed over 100 iterations, meticulously accounting for mean and standard deviation values, thereby mitigating the potential impact of noise and ensuring the attainment of statistically valid conclusions47. Finally, subjects from the Camargo Cohort were used to perform an external validation of the results obtained in the HURH cohort.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abrahamsen, B., van Staa, T., Ariely, R., Olson, M. & Cooper, C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos. Int. 20, 1633–1650 (2009).

Adachi, J. D. et al. Impact of prevalent fractures on quality of life: baseline results from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85, 806–813 (2010).

Black, D. M. & Rosen, C. J. Clinical Practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl. J. Med. 374, 254–262 (2016).

Johansson, L. et al. Decreased physical health-related quality of life-a persisting state for older women with clinical vertebral fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 30, 1961–1971 (2019).

Reid, I. R. A broader strategy for osteoporosis interventions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16, 333–339 (2020).

Cosman, F. et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 2359–2381 (2014).

Kanis, J. A., Johnell, O., Oden, A., Johansson, H. & McCloskey, E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos. Int. 19, 385–397 (2008).

Azagra, R. et al. FRAX® tool, the WHO algorithm to predict osteoporotic fractures: the first analysis of its discriminative and predictive ability in the Spanish FRIDEX cohort. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 13, 204 (2012).

Tebé Cordomí, C. et al. Validation of the FRAX predictive model for major osteoporotic fracture in a historical cohort of Spanish women. J. Clin. Densitom. 16, 231–237 (2013).

González-Macías, J., Marin, F., Vila, J. & Díez-Pérez, A. Probability of fractures predicted by FRAX® and observed incidence in the Spanish ECOSAP study cohort. Bone 50, 373–377 (2012).

Azagra, R. et al. [FRAX® thresholds to identify people with high or low risk of osteoporotic fracture in Spanish female population]. Med. Clin. (Barc). 144, 1–8 (2015).

Leslie, W. D. et al. FRAX for fracture prediction shorter and longer than 10 years: the Manitoba BMD registry. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 2557–2564 (2017).

Hoff, M. et al. Validation of FRAX and the impact of self-reported falls among elderly in a general population: the HUNT study, Norway. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 2935–2944 (2017).

Goldshtein, I., Gerber, Y., Ish-Shalom, S. & Leshno, M. Fracture risk assessment with FRAX using Real-World data in a Population-Based cohort from Israel. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 94–102 (2018).

Leslie, W. D. et al. Does osteoporosis therapy invalidate FRAX for fracture prediction? J. Bone Min. Res. 27, 1243–1251 (2012).

Khanna, V. V. et al. A decision support system for osteoporosis risk prediction using machine learning and explainable artificial intelligence. Heliyon 9, e22456 (2023).

Handelman, G. S. et al. eDoctor: machine learning and the future of medicine. J. Intern. Med. 284, 603–619 (2018).

Sarker, I. H. Machine learning: Algorithms, Real-World applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 160 (2021).

Waring, J., Lindvall, C. & Umeton, R. Automated machine learning: review of the state-of-the-art and opportunities for healthcare. Artif. Intell. Med. 104, 101822 (2020).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16). San Francisco, CA, USA: ACM; pp. 785–794 (2016).

Johansson, H. et al. Imminent risk of fracture after fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 775–780 (2017).

Khalid, S. et al. One- and 2-year incidence of osteoporotic fracture: a multi-cohort observational study using routinely collected real-world data. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 123–137 (2022).

van Geel, T. C. M., van Helden, S., Geusens, P. P. & Winkens, B. Dinant, G.-J. Clinical subsequent fractures cluster in time after first fractures. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 99–102 (2009).

Toth, E. et al. History of previous fracture and imminent fracture risk in Swedish women aged 55 to 90 years presenting with a fragility fracture. J. Bone Min. Res. 35, 861–868 (2020).

Kanis, J. A. et al. Previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk: a meta-analysis to update FRAX. Osteoporos. Int. 34, 2027–2045 (2023).

Chen, T., Wang, Y., Hao, Z., Hu, Y. & Li, J. Parathyroid hormone and its related peptides in bone metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 192, 114669 (2021).

Mavar, M., Sorić, T., Bagarić, E. & Sarić, A. Matek Sarić, M. The power of vitamin D: is the future in precision nutrition through personalized supplementation plans? Nutrients 16, 1176 (2024).

Bouillon, R. et al. Skeletal and extraskeletal actions of vitamin D: current evidence and outstanding questions. Endocr. Rev. 40, 1109–1151 (2019).

Stone, K. L. et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Bone Min. Res. 18, 1947–1954 (2003).

Siris, E. S. et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for Pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1108–1112 (2004).

Bouxsein, M. L. et al. Change in bone density and reduction in fracture risk: A Meta-Regression of published trials. J. Bone Min. Res. 34, 632–642 (2019).

Shevroja, E. et al. Update on the clinical use of trabecular bone score (TBS) in the management of osteoporosis: results of an expert group meeting organized by the European society for clinical and economic aspects of osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal diseases (ESCEO), and the international osteoporosis foundation (IOF) under the auspices of WHO collaborating center for epidemiology of musculoskeletal health and aging. Osteoporos. Int. 34, 1501–1529 (2023).

Shevroja, E. et al. Use of trabecular bone score (TBS) as a complementary approach to Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for fracture risk assessment in clinical practice. J. Clin. Densitom. 20, 334–345 (2017).

Humbert, L. et al. 3D-DXA: assessing the femoral Shape, the trabecular macrostructure and the cortex in 3D from DXA images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 36, 27–39 (2017).

Humbert, L. et al. DXA-Based 3D analysis of the cortical and trabecular bone of hip fracture postmenopausal women: A Case-Control study. J. Clin. Densitom. 23, 403–410 (2020).

Martínez, J. et al. Bone turnover markers in Spanish postmenopausal women: the Camargo cohort study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 409, 70–74 (2009).

Winzenrieth, R. et al. Effects of osteoporosis drug treatments on cortical and trabecular bone in the femur using DXA-based 3D modeling. Osteoporos. Int. 29, 2323–2333 (2018).

Genant, H. K., Wu, C. Y., van Kuijk, C. & Nevitt, M. C. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J. Bone Min. Res. 8, 1137–1148 (1993).

Chen, T. et al. Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R package version 0.4-2. 1, 1–4 (2015).

Cervantes, J., Garcia-Lamont, F., Rodríguez-Mazahua, L. & Lopez, A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: Applications, challenges and trends. Neurocomputing 408, 189–215 (2020).

Charbuty, B. & Abdulazeez, A. Classification based on decision tree algorithm for machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends. 2, 20–28 (2021).

Ampomah, E. K. et al. Stock Market Prediction with Gaussian Naïve Bayes Machine Learning Algorithm. Informatica 45, (2021).

Cubillos, M., Wøhlk, S. & Wulff, J. N. A bi-objective k-nearest-neighbors-based imputation method for multilevel data. Expert Syst. Appl. 204, 117298 (2022).

MATLAB Runtime - MATLAB Compiler. https://es.mathworks.com/products/compiler/matlab-runtime.html

Feurer, M. & Hutter, F. Hyperparameter optimization. in Automated Machine Learning: Methods, Systems, Challenges (eds Hutter, F., Kotthoff, L. & Vanschoren, J.) 3–33 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05318-5_1. (2019).

Chen, R. C., Dewi, C., Huang, S. W. & Caraka, R. E. Selecting critical features for data classification based on machine learning methods. J. Big Data. 7, 52 (2020).

Herland, M., Khoshgoftaar, T. M. & Wald, R. A review of data mining using big data in health informatics. J. Big Data. 1, 2 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the subjects for their participation in the study.

Funding

This research was partly supported by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI21/00532), which was co-funded by European Union FEDER funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RU-M contributed to the conceptualization, data analysis, interpretation, drafting, and critical revision of the article. JM contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, drafting, and critical revision of the draft article. FC-S contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and revising the draft article critically. AMT contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and revising the draft article critically. ARdT contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and revising the draft article critically. JG contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and revising the draft article critically. MM-M contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and critical revision of the draft article. JLH contributed to the acquisition of data, data curation, data analysis, and revising the draft article critically. JLP-C contributed to the conceptualization, data analysis, interpretation, drafting of the article, supervision, and revising it critically. All authors reviewed and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical aspects

The experimental protocol was approved by the Río Hortega University Hospital of Valladolid Ethics Committee (PI-FIS-20-076126) and fully complied with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (2008), Spanish data protection law (LO 15/1999), and specifications (RD 1720/2007). All patients who agreed to participate gave signed written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Usategui-Martín, R., Mateo, J., Campillo-Sánchez, F. et al. Assessment of the risk of osteoporotic bone fracture in postmenopausal women using machine learning methods. Sci Rep 15, 43329 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27226-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27226-z