Abstract

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist, is used in critical care for sedation and sympathetic modulation. However, its association with survival after cardiac arrest remains uncertain.This study investigated the relationship between DEX administration and mortality risk in cardiac arrest patients.This retrospective cohort study utilized the MIMIC-IV database. Adult patients with documented cardiac arrest (as defined by ICD-9/10 codes) prior to intensive care unit (ICU) admission were stratified into DEX-exposed and unexposed groups based on dexmedetomidine administration. The primary outcome was 28-day mortality; secondary endpoints were 90-day and 1-year mortality. Patients were matched 1:1 using propensity score matching (PSM) based on key baseline characteristics such as demographics, comorbidities, and illness severity scores to minimize confounding. Robustness was assessed through sensitivity analyses and adjusted multivariable Cox regression. Among 1,342 patients, 314 (23.4%) received DEX. After PSM (269 matched pairs), DEX exposure were associated with significantly lower mortality rates at 28 days (90/269 [33.5%] vs. 150/269 [55.8%]), 90 days (112/269 [41.6%] vs. 165/269 [61.3%]), and 1 year (128/269 [47.6%] vs. 180/269 [66.9%]). Multivariable analysis showed DEX administration was independently associated with lower mortality at 28-day (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.27–0.48, p < 0.001), 90-day (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.32–0.54, p < 0.001), and 1-year (HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.34–0.56, p < 0.001). These associations remained consistent across sensitivity analyses and subgroups stratified by gender, age, comorbidity burden, and illness severity scores. DEX administration demonstrated a significant association with improved survival in post-cardiac arrest patients, suggesting a potential role in post-cardiac arrest management. Prospective studies are warranted to confirm its clinical efficacy and safety in post-arrest management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac arrest remains a major global public health concern, with persistently low survival rates despite medical advances. According to the 2022 Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), the survival-to-discharge rate for emergency medical services(EMS)-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is 9.3%, with U.S. state rates ranging from 5.5% to 15.4%1. Further quantifying the in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) burden, a Medicare population analysis revealed an average risk-adjusted incidence of 8.5 per 1,000 admissions, with significant interhospital variability1. Although IHCA survival is slightly higher—about 25% in advanced healthcare systems,yet significant gaps remain in optimizing outcomes2. These persistently poor survival rates, despite advances in resuscitation and emergency care, underscore the urgent need for innovative therapies and system-level interventions.

Among various post-resuscitation interventions, sedation and analgesia play a vital role in ensuring patient comfort, hemodynamic stability, and potentially neurological recovery3. Commonly used agents include propofol, benzodiazepines, and α2-adrenergic agonists such as dexmedetomidine4. Emerging translational evidence demonstrates that targeted sedation can induce neuroprotective slow-wave oscillations in murine cerebral activity, correlating with improved survival5. Similarly, porcine models have shown enhanced cardiocerebral outcomes through analgesia-mediated attenuation of sympathetic overstimulation6.

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist with established sedative and organoprotective properties, has demonstrated therapeutic potential across diverse critical care populations: It may reduce in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) management7; enhance survival without significant adverse reactions like hypotension or seizures in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients8 and promote renal recovery while reducing mortality in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury9.These beneficial effects—potentially mediated by anti-inflammatory action10, sympathetic modulation11, and organ protection12—are pathophysiologically relevant to post-cardiac arrest care. Despite these promising results, evidence regarding cardiac arrest outcomes remains limited, and current guidelines lack recommendations on DEX for cardiac arrest, prompting further investigation into its effects on mortality rates in this population.

This study aimed to evaluate the association between DEX administration and survival outcomes in cardiac arrest patients admitted to the ICU.

Methods

Data source

This observational cohort study adhered to the STROBE(Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines13. We utilized the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC)-IV version 3.0 database14. This database contains de-identified clinical records of over 90,000 critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care units (ICUs) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, including all eligible ICU admissions from 2008 to 2022 with complete clinical documentation15. Ethical oversight was approved by the institutional review boards(IRBs) of both BIDMC and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). As MIMIC-IV complies with HIPAA Safe Harbor standards, individual consent was waived. Data access was authorized via CITI program certification (ID: 55071275).

Participants

This large-scale retrospective cohort study utilized International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9; code 4275) and Tenth Revision (ICD-10; codes I46, I462, I468, I469) to identify hospitalized adults with cardiac arrest. The study included both out-of-hospital and in-hospital cardiac arrest patients prior to ICU admission. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) age < 18 years; (2) ICU length of stay < 24 h; and (3) cardiac arrest events occurring post-ICU admission to exclude secondary events unrelated to the initial ICU admission indication. For patients with multiple ICU admissions, only the first qualifying admission was analyzed. The cohort was stratified based on DEX exposure status during ICU care: the DEX group received ≥1 dose after ICU admission, while the comparison group had no documented DEX administration (Non-DEX).

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed using PostgreSQL via Navicat Premium to acquire critical parameters documented within the first 24 hours of ICU admission. The retrieved variables encompassed: (1) Demographic characteristics: gender, age, ethnicity, marital status; (2) Vital signs: heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), respiratory rate (RR), core temperature, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂); (3) Laboratory parameters: white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin, platelets, potassium, sodium, calcium, anion gap (AG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin (TBIL), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT); (4) Comorbidities: pre-existing conditions including myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), chronic pulmonary disease (CPD), diabetes, renal disease, malignant cancer, liver disease, sepsis, acute kidney injury (AKI); (5) Illness severity scores: Acute Physiology Score III (APSIII), Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPSII), Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS), and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score calculated within 24 hours of ICU admission; (6) Concomitant Interventions: defibrillation events, mechanical ventilation duration, vasopressor administration duration and concurrent sedation agents (propofol/midazolam). Outliers were addressed by integrating clinical plausibility with the Tukey method16. Missing data were addressed with multiple imputation by chained equations to better account for uncertainty17.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 28-day all-cause mortality after cardiac arrest. Prespecified secondary outcomes included 90-day and 1-year all-cause mortality, assessed through longitudinal follow-up. Mortality was ascertained from hospital records and, when applicable, linked national death registries included in MIMIC-IV.

Statistical analysis

Given significant baseline heterogeneity and the observational design, propensity score matching (PSM) was implemented using a 1:1 nearest-neighbor algorithm (caliper=0.2) to balance baseline characteristics between dexmedetomidine (DEX) and non-dexmedetomidine (Non-DEX) cohorts18. PSM was selected over regression adjustment alone for its capacity to directly harmonize cohorts and enhance clinical interpretability of group comparisons. Covariates included demographics, vital signs, laboratory parameters, comorbidities, illness severity scores, and concomitant interventions. Balance was rigorously assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with SMD < 0.1 indicating adequate covariate balance. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range[IQR]), while categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed using independent t-tests for normally distributed data or Mann-Whitney U tests for non-parametric data, while categorical variables were compared via chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate.

The robustness of primary findings was assessed through multi-model sensitivity analyses incorporating five distinct causal inference approaches: (1) propensity score adjustment (PSA)18, (2) inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)19, (3) standardized mortality ratio weighting (SMRW)20, (4) pairwise algorithmic matching (PA)21, and (5) overlap weight (OW)22. Effect estimates, associated confidence intervals, and significance levels were systematically quantified and comparatively analyzed across all models. To address potential effects of DEX infusion duration and timing, exploratory analyses were performed using continuous and categorical variables for infusion duration, as well as early (≤ 72 h) versus late (> 72 h) initiation relative to ICU admission.

Survival probabilities were illustrated with Kaplan–Meier survival curves for both unmatched and matched cohorts, with between-group differences assessed by log-rank tests. Proportional hazards assumptions for Cox models were verified using Schoenfeld residuals. Where violations occurred (global test p < 0.05), extended Cox models with time-dependent covariates were implemented, incorporating covariates selected through tripartite criterion: (1) significant univariate associations (p < 0.05), (2) established prognostic relevance in prior literature, and (3) clinical plausibility as adjudicated by our multidisciplinary critical care team. Multivariable Cox regression modeling was employed for primary outcome analysis, with derived hazard ratios (HRs) accompanied by 95% confidence intervals enabling multidimensional appraisal.

Subgroup analysis was conducted to determine mortality-modifying effects of dexmedetomidine exhibited differential patterns across demographic/clinical strata including gender, age, comorbidities, severity score and use of other sedatives. Preceding this stratification, interaction term evaluations incorporating P-values for effect modification were systematically applied across all predefined cohorts to verify baseline characteristic homogeneity. Interaction P-values for subgroup analyses were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni method to account for multiple comparisons across predefined strata.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.2.2 (http://www.Rproject.org; The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and Free Statistics software version 2.2.0 (Beijing FreeClinical Medical Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China)23,24,25. Statistical evaluations universally adopted bidirectional hypothesis verification, employing an alpha threshold of 0.05 as the demarcation criterion.

Results

Baseline characteristics

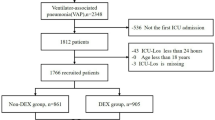

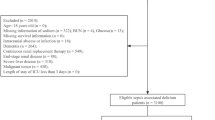

The final cohort comprised 1,342 cardiac arrest patients meeting inclusion criteria, stratified into DEX (n = 314, 23.4%) and non-DEX (n = 1,028) groups (Fig. 1). Pre-matching analyses showed significant differences: DEX recipients were younger (62.5 ± 16.1 vs. 66.5 ± 17.0 years; SMD = 0.247), more frequently male (70.1% vs. 60.2%; SMD = 0.208), and exhibited greater acute morbidity burdens, including sepsis (85.7% vs. 65.4%; SMD = 0.486), AKI(92.4% vs. 88.5%; SMD = 0.131), and SOFA scores (median 10.0 [IQR 7.0–12.0] vs. 8.0 [5.0–11.0]; SMD = 0.356). Critical care interventions differed, with longer mechanical ventilation duration (median 3.4 [1.6–6.6] vs. 1.7 [0.8–4.0] days; SMD = 0.420) and extended vasopressor dependency (median 2.7 [1.2–6.3] vs. 1.5 [0.6–2.9] days; SMD = 0.536) observed in the DEX cohort. PSM incorporating all prespecified covariates from the Methods section, yielded 269 matched pairs. Most covariates had SMD < 0.1 after matching (Table 1), confirming that initial imbalances were effectively resolved. Variables with significant pre-matching imbalances (e.g., SOFA score, sepsis, mechanical ventilation duration) achieved SMD < 0.05 post-matching(Table 1).

ICU, intensive care unit; MIMIC IV, Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis before and after PSM

Survival probabilities were visually represented using Kaplan-Meier curves for both unmatched and propensity-matched cohorts, with between-group differences assessed via log-rank testing. Before PSM, the DEX group exhibited notably higher survival rates at 28 days, 90 days, and 1 year, with p-values less than 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant advantage(Fig. 2. A1,A2,A3;Table S1). After PSM, these differences persisted, suggesting that DEX administration is associated with improved survival outcomes even after adjusting for baseline characteristics. The consistent significance of the p-values post-matching underscores the robustness of the observed survival benefit linked to DEX use(Fig. 2. B1,B2,B3;Table S1).KM curves demonstrated significant survival differences (log-rank p < 0.0001), while Cox regression quantified hazard ratios for mortality (Table 2).

Notes: (A1) 28-day mortality before PSM; (A2) 90-day mortality before PSM; (A3) 1-year mortality before PSM; (B1)28-day mortality after PSM; (B2)90-day mortality after PSM; (B3)1-year mortality after PSM.Abbreviation: PSM, propensity score matching; DEX, dexmedetomidine.

Primary and secondary outcomes analysis with PSM cohorts

28-day mortality was significantly lower in the DEX group (98/314 [31.2%] vs. 548/1028 [53.3%]). This survival advantage persisted at 90 days (129/314 [41.1%] vs. 605/1028 [58.9%]) and 1-year follow-up (147/314 [46.8%] vs. 656/1028 [63.8%]). Forest plot analyses across seven analytical models—univariate, multivariate Cox, propensity score adjustment (PSA), propensity score matching (PSM), inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), standardized mortality ratio weighting (SMRW), pairwise algorithmic matching (PA), and overlap weighting (OW)—consistently demonstrated mortality reduction associated with DEX exposure (Fig. 3). For 28-day mortality, hazard ratios (HRs) ranged from 0.38 to 0.53 across models (p < 0.001 for all) (Fig. 3A). The concordance of hazard ratios across all seven models (Fig. 3), with narrow confidence intervals and consistent directionality, indicates robustness of the observed treatment effect against potential residual confounding. The 90-day mortality analysis yielded HRs of 0.44–0.59, maintaining significance (p < 0.001), including IPTW (p = 0.001) (Fig. 3B). One-year mortality patterns mirrored these findings (HRs: 0.46–0.61; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3C). All sensitivity analyses corroborated the primary outcome directionality.

Abbreviation: DEX, dexmedetomidine. IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; SMRW, standardized mortality ratio weighting; PA, pairwise algorithmic; OW, overlap weight.

Cox regression analysis before and after PSM

Global tests of Schoenfeld residuals indicated violations of the proportional hazards (PH) assumption for all mortality endpoints (all p < 0.001). However, visual inspection of residual plots revealed no systematic temporal patterns (Figure S1;Table S2). Sensitivity analyses with time-dependent covariates yielded consistent hazard ratios (Table 2), supporting the robustness of primary findings.

In the original cohort, unadjusted Cox regression revealed a 55% reduction in 28-day mortality risk with DEX exposure (HR 0.45, 95% CI: 0.36–0.56; p < 0.001). Sequential adjustment for confounders across Models 1–5 demonstrated progressively stronger protective effects, with fully adjusted HRs decreaing from 0.44 to 0.38 (all p < 0.001). Post-propensity matching analyses corroborated these findings: the unadjusted matched cohort showed a 53% mortality risk reduction (HR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.36–0.61; p < 0.001), intensifying to 64% risk reduction in the fully adjusted Model 5 (HR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.27–0.48; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Similar trends were observed for both 90-day and 1-year mortality. For 90-day mortality, the crude HR of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.44–0.64, p < 0.001) in the original cohort improved to 0.44 (95% CI: 0.36–0.54, p < 0.001) after full adjustment, while in the PSM cohort, the HR decreased from 0.52 (95% CI: 0.41–0.66, p < 0.001) to 0.42 (95% CI: 0.32–0.54, p < 0.001). For 1-year mortality, the protective effect of DEX remained robust, with the fully adjusted HR reaching 0.46 (95% CI: 0.38–0.56, p < 0.001) before PSM and 0.44 (95% CI: 0.34–0.56, p < 0.001) after PSM(Table 2).

Model 1 was adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity and marital status; Model 2 was additionally adjusted for HR, MAP, RR, temperature, SPO2, glucose, WBC, hemoglobin, platelets, potassium, sodium, calcium, AG, ALT, AST, ALP, TBiL, BUN, creatinine, INR, PT, PTT; Model 3 was additionally adjusted for MI, CHF, CVD, CPD, diabetes, malignant cancer, liver disease, sepsis and AKI; Model 4 was additionally adjusted for APSIII, SAPSII, OASIS and SOFA; Model 5 was additionally adjusted for defibrillation, ventilation duration, vasopressor duration, the ues of propofol and midazolam. Abbreviation: PSM, propensity score matching; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, pulse oxygen saturation; WBC, white blood cell; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; TBIL, total bilirubin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; INR, international normalized ratio; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; CPD, chronic pulmonary disease; AKI, acute kidney injury; APSIII, Acute Physiology Score III; SAPSII, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; OASIS, Oxford Acute Severity of Illness score; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Subgroup analysis

Stratified subgroup analyses of 28-day (Supplementary Figure S2 and Table S3), 90-day (Figure S3 and Table S4), and 1-year mortality (Figure S4 and Table S5) revealed a consistent association between dexmedetomidine exposure and reduced mortality across most demographic and clinical subgroups, including age, sex categories, and comorbidity burdens. Interaction tests indicated statistically significant effect modifications in the age subgroup for 90-day (p-interaction = 0.042) and 1-year mortality (p-interaction = 0.029). No significant interactions were observed in other subgroups (all p-interaction > 0.05; range: 0.11–0.92). Despite these interactions, hazard ratios remained below 1.0 in all age strata, suggesting preserved risk reduction associated with dexmedetomidine exposure. Table S6 summarize the associations between DEX infusion parameters and mortality. Each additional hour of DEX infusion was associated with a 7% reduction in 28-day mortality (aHR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90–0.96, p < 0.001), though this effect dissipated at 1 year (aHR 1.00, p = 0.42). Notably, early initiation (≤ 72 h post-ICU) was associated with markedly reduced 28-day mortality (aHR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00–0.72, p = 0.03).

Discussion

This investigation revealed a statistically significant and robust association between DEX administration and reduced mortality risk in post-cardiac arrest patients. This favorable association persisted after rigorous adjustment for multiple confounding factors using various statistical approaches, including propensity score matching (PSM) and sensitivity analyses. Subgroup analyses further indicated consistent associations between DEX and survival outcomes across diverse patient subgroups. Crucially, the association remained statistically robust following comprehensive baseline adjustment using PSM, demonstrating a significant link between DEX and survival in this population. The survival advantage was consistently observed across multiple time points, suggesting potential long-term benefits.

To our knowledge, this represents the first investigation documenting an association between DEX administration and improved survival in cardiac arrest patients, thus providing novel evidence for this vulnerable cohort. Although prior studies suggest the benefits of DEX in other critically ill populations, physiological differences in cardiac arrest recovery warrant cautious extrapolation of these results. However, our results align directionally with established benefits observed elsewhere: Specifically, Wang et al. reported a 38% risk reduction in acute kidney injury (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.55–0.70)26, Zhao et al. demonstrated a 69% decrease in ventilator-associated sepsis mortality (HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.23–0.42)27, and Shi et al. documented improved survival in mechanically ventilated patients28. Notably, our analysis revealed a comparable magnitude of association in cardiac arrest patients (PSM-adjusted 28-day HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.27–0.48), with point estimates closely approaching those in the Zhao et al. study. The consistency across heterogeneous populations – a 64% risk reduction (HR 0.36) in our primary analysis versus 69% in Zhao et al. – reinforces the possibility of a consistent underlying association pattern. This observed relationship may reflect DEX’s dual neuroprotective and hemodynamic-stabilizing properties during post-resuscitation care, a mechanism that is biologically plausible given cardiac arrest pathophysiology.

Our results highlight a population-specific response pattern to DEX that diverges significantly from prior ICU literature. While Li and Yue29reported no survival benefit of DEX in epilepsy patients, our cardiac arrest cohort exhibited a marked absolute risk reduction (31.2% vs. 53.3%). Similarly, the SPICE-III trial30 reported increased mortality with high-dose DEX in younger general ICU patients (HR 1.30, 95% CI 1.03–1.65; p = 0.029), directly contrasting with our observation of consistent survival benefit across all age strata. These discrepancies likely reflect distinct pathophysiological contexts: SPICE-III enrolled a general ICU population (median age 64.7 years, 60.5% sepsis), whereas our cohort comprised post-cardiac arrest patients (median age 62.5 years, 85.7% sepsis) subjected to catecholamine surge and reperfusion injury, conditions in which DEX’s sympatholytic and anti-inflammatory properties may confer unique survival advantage. These divergent findings may reflect context-dependent biological responses to DEX, warranting population-specific investigation in critical care settings.

Experimental studies elucidate potential mechanisms underlying DEX’s protective effects in cardiac arrest. Swine models demonstrate improved post-resuscitation cardiac and neurological outcomes through inhibition of inflammatory and apoptosis pathways6, consistent with neuroprotection via anti-neuroinflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects in rat models31. These preclinical findings support the hypothesis that the observed clinical benefits of DEX may stem from its dual mechanisms: anti-inflammatory properties via inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release5, and sympatholytic effects promoting hemodynamic stability27,28,32. Critically, while preclinical evidence supports organ protection, clinical application requires vigilance for potential hemodynamic adverse events (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension). The absence of real-time hemodynamic parameters in the MIMIC-IV database precluded quantification of these risks in our study. Future investigations integrating continuous hemodynamic monitoring are essential to establish the definitive benefit-risk profile of DEX therapy in this setting.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, despite employing PSM and multiple sensitivity analyses, residual confounding from unmeasured variables cannot be entirely excluded. Second, heterogeneous DEX administration protocols (including dosing and timing variability) limit clinical generalizability. Third, MIMIC-IV lacks granular laboratory biomarkers for mechanistic exploration. Fourth, violations of the proportional hazards assumption were observed in Cox models, though sensitivity analyses confirmed the stability of our primary findings. Fifth, the absence of continuous hemodynamic monitoring precluded assessment of DEX-related adverse effects (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension). Prospective trials with protocolized DEX and safety surveillance are warranted. While proportional hazards (PH) violations were observed, consistent results from extended Cox models support the robustness of primary findings. The survival benefit was most pronounced within the first 28 days, aligning with the critical post-arrest recovery phase.

Conclusion

This observational study identified an association between DEX exposure and improved survival outcomes in resuscitated cardiac arrest patients. This benefit is potentially mediated through anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective pathways. Our findings indicate that DEX represents a promising adjunct therapeutic agent for post-cardiac arrest management. However, robust multicenter randomized controlled trials remain imperative to definitively establish its clinical efficacy and define effective and safe administration strategies in this high-risk population.

Data availability

Raw clinical data is publicly available via PhysioNet. Analysis code and derived datasets are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Martin, S. S. et al. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of us and global data from the american heart association. Circulation 149(8), e347–e913 (2024).

Soar, J. In-hospital cardiac arrest. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 29(3), 181–185 (2023).

Chalkias, A., Adamos, G. & Mentzelopoulos, S. D. General critical Care, temperature Control, and End-of-Life decision making in patients resuscitated from cardiac Arrest. J. Clin. Med. 12(12), 4118 (2023).

Ceric, A. et al. Sedation and analgesia in post-cardiac arrest care: a post hoc analysis of the TTM2 trial. Critical Care 29(1), 247 (2025).

Ikeda, T. et al. Post-cardiac arrest sedation promotes electroencephalographic Slow-wave activity and improves survival in a mouse model of cardiac Arrest. Anesthesiology 137(6), 716–732 (2022).

Shen, R. et al. The effects of Dexmedetomidine post-conditioning on cardiac and neurological outcomes after cardiac arrest and resuscitation in swine. Shock (Augusta Ga) 55(3), 388–395 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Dexmedetomidine administration is associated with improved outcomes in critically ill patients with acute myocardial infarction partly through its anti-inflammatory activity. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1428210 (2024).

Liu, S. Y. et al. Association of early Dexmedetomidine utilization with clinical and functional outcomes following Moderate-Severe traumatic brain injury: A transforming clinical research and knowledge in traumatic brain injury Study. Crit. Care Med. 52(4), 607–617 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Association between Dexmedetomidine administration and outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Anesth. 83, 110960 (2022).

Wu, W. et al. Dexmedetomidine mitigates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by modulating heat shock protein A12B to inhibit the toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 398, 111112 (2024).

Bo, J.-H. et al. Dexmedetomidine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced sympathetic activation and sepsis via suppressing superoxide signaling in paraventricular nucleus. Antioxid. (basel Switzerland) 11(12), 2395 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Dexmedetomidine alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting autophagy through PI3K/akt/mTOR pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 54(3), 173–181 (2023).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. (London England) 12(12), 1495–1499 (2014).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10(1), 1 (2023).

Johnson, A. et al. Mimic-iv. PhysioNet.

Muñoz Monjas, A. et al. Automatic outlier detection in laboratory result distributions within a real world data network. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 302, 88–92 (2023).

Ten Berg, S. et al. Milrinone versus Dobutamine in acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock; a propensity score matched analysis.Clin. Res. Cardiology: Official J. German Cardiac Soc., (2025).

Austin, P. C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational Studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 46(3), 399–424 (2011).

Austin, P. C. & Stuart, E. A. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies[J]. Stat. Med. 34 (28), 3661–3679 (2015).

Sato, T. & Matsuyama, Y. Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization. Epidemiol. (Cambridge Mass) 14(6), 680–686 (2003).

Li, L. & Greene, T. A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis. Int. J. Biostatistics 9(2), 215–234 (2013).

Zajichek, A. M. & Grunkemeier, G. L. Propensity scores used as overlap weights provide exact covariate balance. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 66(3), ezae318 (2024).

Ruan, Z. et al. Association between psoriasis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among outpatient US adults. JAMA Dermatology 158(7), 745–753 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. C-reactive protein/lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker in acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional study assessing disease severity. Int. J. Surg. (London England) 110(6), 3223–3229 (2024).

Huang, W. et al. The mixed effect of Endocrine-Disrupting chemicals on biological age acceleration: unveiling the mechanism and potential intervention target. Environ. Int. 184, 108447 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Impact of Dexmedetomidine on mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a retrospective propensity score matching analysis. BMJ open. 13(11), e073675 (2023).

Zhao, S. et al. Effect of age and ICU types on mortality in invasive mechanically ventilated patients with sepsis receiving dexmedetomidine: a retrospective cohort study with propensity score matching[J]. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1344327 (2024).

Shi, X. et al. Effect of different sedatives on the prognosis of patients with mechanical ventilation: a retrospective cohort study based on MIMIC-IV database. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1301451 (2024).

Li, X. & Yue, W. Comparative analysis of dexmedetomidine, midazolam, and Propofol impact on epilepsy-related mortality in the ICU: insights from the MIMIC-IV database.BMC Neurol. 24 (1), 193 (2024).

Shehabi, Y. et al. Dexmedetomidine and Propofol sedation in critically ill patients and Dose-associated 90-Day mortality: A secondary cohort analysis of a randomized controlled trial (SPICE III). Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 207(7), 876–886 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Dexmedetomidine post-conditioning attenuates cerebral ischemia following asphyxia cardiac arrest through down-regulation of apoptosis and neuroinflammation in rats. BMC Anesthesiol. 21(1), 180 (2021).

Yuan, Y. et al. Effects of Dexmedetomidine on minimum alveolar concentration of Sevoflurane for blunting sympathetic response to pneumoperitoneum: a randomized trial. Drug Des. Dev. Therapy 19, 5899–5909 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are particularly indebted to Physician-Scientist Team from Beijing Institute for Physician Scientist for their critical insights into the study methodology, statistical expertise, and manuscript review.

Funding

Henan Provincial Key Project of Medical Science and Technology Research Plan (SBGJ202102155); Key Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Henan Province (22A320067); Key project of the National Key Research and Development Plan on Common Disease Prevention Research (2021YFC2501800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyi Zhang (SYZ) conceived the research framework, conducted data extraction and analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. Yao Luo (YL) supervised the entire research process, provided strategic guidance on experimental design, and conducted rigorous scholarly appraisal of the research. Qiang Zhang (QZ) contributed to data validation and resource acquisition. Jie Liu (JL) was responsible for manuscript refinement and revision. Chao Lan (CL) provided overall direction and quality control for the study and conducted the final review of the manuscript. All authors have thoroughly reviewed the final manuscript and consented to its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Luo, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. Impact of dexmedetomidine administration on mortality in patients with cardiac arrest: a propensity score matching analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 15, 43333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27295-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27295-0