Abstract

Patients receiving hemodialysis (HD) often experience fatigue and reduced quality of life due to the chronic physical and psychological burden of treatment. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) and Physical Exercise (PE), show promise in alleviating these symptoms. This study aimed to compare the effects of PMR and PE on subjective well-being and fatigue in patients with HD. An individually randomized parallel-group trial was conducted with 66 patients receiving hemodialysis recruited from two centers in Mashhad, Iran. Participants were randomly assigned to either the PMR group (n = 34) or the PE group (n = 32). The PMR group received structured relaxation training, while the PE group performed selected stretching and balance exercises over four weeks. Outcomes were assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) and the Subjective Well-being Scale (SWS) before and after the intervention. Both interventions led to highly significant improvements in all domains of subjective well-being (emotional, psychological, and social) and the Total Subjective Well-being score from baseline (p < 0.001). Crucially, the PMR group achieved a significantly higher Total Subjective Well-being score post-intervention compared to the PE group (p = 0.03; Cohen’s d = 0.57). Fatigue levels also decreased significantly in both groups (p < 0.001), although the difference between the PMR and PE groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.12). Furthermore, demographic factors, including employment status and HD frequency, significantly influenced total well-being. Both PMR and PE are practical and viable non-pharmacological strategies for enhancing subjective well-being and reducing fatigue in patients with HD. However, the PMR intervention demonstrated a superior effect on the overall subjective well-being score. Future studies should investigate the combination of these approaches for optimal patient rehabilitation.

Trial Registration: This study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) with the unique identifier IRCT20201227049856N1 on 2021-02-15. The trial record can be accessed on the official IRCT website: https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/trial/53463.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive condition that may lead to kidney failure, requiring replacement therapy, most commonly hemodialysis (HD)1. CKD is projected to become the fifth leading cause of death globally by 2040. The prevalence of Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is significant, and it rises by around 15% in Iran2. Patients receiving HD face numerous challenges, including fatigue, cramps, depression, and sleep disorders, all negatively affecting quality of life (QOL)3,4. Among HD challenges, Fatigue often arises from extended dialysis, dietary restrictions, stress, and the body’s physiological response to these factors. Additionally, it may be linked to muscle breakdown caused by acidosis, inflammation, or insulin resistance, leading to decreased physical activity and muscle fatigue5. Poor Subjective Well-being (SWB) is another common issue, encompassing general life satisfaction and a balance of positive and negative emotions, which is often compromised by the burden of chronic illness. Additionally, sleep disruption can result in reduced QOL, heightened drug consumption, and mortality rates. In this way, a multinational research project discovered that some chronic illnesses were significantly linked to sleep disturbances, including chronic kidney disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, and stroke. Sleep disruption in COPD patients correlates with the length of the illness and pain6. To address these widespread issues and improve the overall SWB and QOL, non-pharmacological therapies are increasingly sought. To address these issues, non-pharmacological therapies include physical activity, light therapy, mind–body techniques (such as PMR and yoga), acupressure, back massage, and chamomile extract beverages, which can enhance various aspects of well-being7,8. PMR is a supplementary therapy created by Jacobson in the 1920s. It involves deliberately tensing and relaxing major muscle groups in a systematic manner. The goal is to reduce chronic muscle tension caused by pain-induced sympathetic arousal by enhancing awareness of muscle tension and relaxation, hence encouraging a relaxation response. PMR typically begins with the toes and progresses to major muscle groups, including the feet, calves, thighs, arms, hands, and neck9,10,11. Considering the positive effects of exercise and PMR on reducing daily fatigue and improving the overall subjective well-being and QOL of dialysis patients, this study aims to examine the impact of these interventions (PE and PMR) on subjective well-being and fatigue as measured through the MFI and QOLS12.

Methods

Trial design

This randomized two-group clinical trial included 70 patients at Mantasarih and 17 Shahrivar hospitals in Mashhad, Iran, in 2021 (Fig. 1). The study evaluated the effects of PMR and PE on subjective well-being and fatigue in patients with HD. Crucially, this was an individually randomized trial, not a cluster-randomized trial. Participants were randomized at the individual level, not by hospital or dialysis unit. This design ensured that the treatment allocation was independent of the hospital setting. The trial record can be accessed on the official IRCT(website: https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/trial/53463).

Participants

The study’s inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) To continue treatment in the dialysis unit as a chronic patient, (2) individuals must be at least 18 years old, (3) have received HD treatment for over 6 months, (4) and possess basic literacy, (4) Participants must possess proficient communication skills, (5) be mentally healthy according to hospital psychologists, (6) consent to take part in the study and engage in relaxing techniques. (7) Potential eligibility criteria include having used the educational material, (8) not engaging in sports programs for the past six months, and (9) not using antidepressants or sedatives. The exclusion criteria include: (1) Lack of cooperation in the study, (2) exercising less than twice a week, (3) patient death or travel, (4) changing dialysis centers, (5) kidney transplant, (6) peritoneal dialysis, (7) use of sedatives or anti-anxiety medications.

Randomization and blinding

Individual participants were randomly assigned to one of the two intervention groups (PMR or Physical Exercise) using a computer-generated random sequence created in Microsoft Excel. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researchers enrolling participants. Due to the nature of the behavioral interventions, neither participants nor those delivering the interventions could be blinded. However, the outcome assessors and the statistician performing the data analysis were blinded to the group assignments. (Note: Further details on the randomization procedure and contamination control are provided in the Sample Size and Randomization section).

Outcome

Data were collected using four instruments developed or selected based on the study objectives and previous research. The Participant Selection Form was designed in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria derived from similar studies and expert consultation. The Demographic and Clinical Information Questionnaire gathered baseline data including age, gender, education level, marital and employment status, economic condition, duration and frequency of hemodialysis, comorbidities, and relevant biochemical indices. Both instruments were reviewed and approved by a panel of seven nursing faculty members to ensure content validity, clarity, and relevance. Necessary revisions were made following their feedback, and reliability was confirmed through expert agreement and item consistency.

The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), developed by Smets et al. (1996)13, was employed to assess the multidimensional nature of fatigue among hemodialysis patients. This 20-item scale consists of five subscales: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater fatigue. The instrument has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in diverse populations, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above 0.80 for most subscales. In the current study, the content validity of the Persian version was verified by seven experts, and internal consistency reliability was confirmed through a pilot test on 10 patients (α = 0.70–0.92 across subscales)14.

The Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWS) by Keyes and Magyar-Moe (2003)15 was used to evaluate emotional, psychological, and social well-being. The 45-item scale includes 12 items for emotional well-being (5-point Likert), 18 items for psychological well-being, and 15 items for social well-being (both on 7-point Likert scales). Higher scores indicate greater levels of well-being. The Persian version of this scale has previously demonstrated satisfactory validity and reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.61 to 0.86. In the present study, content validity was confirmed through an expert panel review, and internal consistency reliability was assessed in a pilot sample of 10 hemodialysis patients, yielding alpha coefficients of 0.84 (emotional), 0.85 (psychological), 0.71 (social), and 0.78 (overall well-being)16,17.

Data collection

After obtaining ethical approval from the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee and with formal coordination with hospital and faculty administrators, the study was conducted on hemodialysis patients at Montaseriyeh and 17 Shahrivar Hospitals in Mashhad, Iran. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, including age, dialysis vintage, and comorbidities, were collected through a combination of patient interviews and medical record reviews at enrollment. The intervention content, comprising selected stretching exercises and PMR, was developed based on an extensive literature review and expert consultation. Instructional videos were produced by the research team, reviewed by academic advisors, and revised accordingly. Eligible participants provided written informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the study objectives. Before intervention, baseline data were collected using demographic and clinical data forms, the Keyes & Magyar-Moe Subjective Well-being Scale (SWS, 2003), and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI, Smets et al., 1996). Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their data. Relevant laboratory tests were obtained from hospital records and information systems.

In the PMR group, Jacobson’s PMR technique was taught in two individual sessions (50–60 min each). The first session involved direct instruction; the second included review and Q&A. Participants also received an instructional video and were asked to perform PMR twice daily for four weeks, including during dialysis sessions. Weekly monitoring was conducted via phone or in-person visits. The relaxation protocol included 18 sequential muscle group contractions (5–10 s), followed by relaxation (5 s), and was combined with synchronized breathing techniques (Supplementary 1).

In the stretching group, an exercise program comprising 10 selected stretching and balance movements was designed with expert input. Patients received one instructional session and an accompanying video. Exercises were performed at home four times a week (on non-dialysis days and Fridays) over four weeks. Each movement was held for 10–30 s and repeated 4–6 times, with emphasis on safe, tolerable execution. Similar to the PMR group, weekly follow-ups were conducted via phone or in-person visits during dialysis sessions to monitor adherence, address concerns, and ensure the correct technique was being used. Both interventions lasted four weeks. Post-intervention assessments using the same instruments were conducted after the final session (supplementary 2).

Sample size and randomization

The required sample size was calculated using the standard formula for comparing two mean values, estimating 35 participants per group to achieve 80% statistical power (β = 0.20) at a 95% confidence interval (α = 0.05). The calculation was based on detecting a medium effect size for Subjective Well-being. This was an individually randomized parallel-group trial. Participants were assigned to the PMR or PE group using a computer-generated random sequence. Crucially, the participants’ pre-existing dialysis session schedule (i.e., odd vs. even days) was not used as a factor or a stratum in the randomization process; allocation was entirely independent of the schedule. We acknowledge concerns regarding the multi-center setting; however, to prevent information contamination between the two intervention groups following individual randomization, the scheduling of the PMR and PE instruction and monitoring sessions was deliberately managed by separating participants based on their existing dialysis session day. This approach served as an administrative arrangement for contamination control, and not a step in the allocation process. The final sample of 66 participants (34 in PMR and 32 in PE) was sufficient to meet the power requirements. All outcome assessors and statisticians remained blinded to the intervention assignments.

Statistical methods

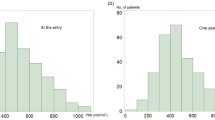

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 21). The normality of the data distribution was assessed using both graphical methods (histograms and Q-Q plots) and the Shapiro–Wilk test. All analyses were performed based on the intention-to-treat principle, with a significance level of p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. Between-group comparisons of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were conducted using independent samples t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The primary analysis utilized Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the effectiveness of the two interventions on post-intervention scores of subjective well-being and fatigue. This model controlled for baseline scores of the outcome variable, providing greater statistical power and adjustment for pre-existing differences. This approach is particularly suitable for our individually randomized trial design. Within-group changes from baseline to post-intervention were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Relationships between key variables were examined using bivariate correlation analysis. All statistical tests were selected based on the data’s distribution characteristics.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the 70 participants was 48.12 ± 13.24 years. The average duration of hemodialysis was 53.46 ± 31.67 months in the physical exercise (PE) group and 50.41 ± 51.54 months in the progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) group. As shown in Table 1, the two groups were homogeneous at baseline. No statistically significant differences were found across demographic or clinical variables including gender (χ2 = 2.21, p = 0.15), marital status (χ2 = 1.11, p = 0.58), education (χ2 = 5.72, p = 0.13), employment status (χ2 = 2.38, p = 0.50), or duration of hemodialysis (Z = − 0.44, p = 0.66).

Effects on subjective well-being

Both interventions produced significant within-group improvements across all domains of subjective well-being (emotional, psychological, and social), as well as in total well-being scores (all p < 0.001; see Table 2). Post-intervention, between-group comparisons showed no statistically significant differences for the emotional (47.44 ± 3.55 vs. 46.25 ± 3.91; t(64) = − 1.29, p = 0.19, d = 0.32), psychological (102.32 ± 8.59 vs. 99.00 ± 9.27; t(64) = − 1.51, p = 0.14, d = 0.37), and social (79.91 ± 7.50 vs. 77.31 ± 5.45; t(64) = 1.60, p = 0.11, d = 0.40) well-being subscales. However, the PMR group achieved a higher total well-being score after intervention (229.61 ± 14.49) compared with the PE group (222.09 ± 12.14), yielding a statistically significant difference (t(64) = 2.28, p = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.57).

Effects on fatigue

Both the PMR and PE groups showed significant reductions in fatigue from baseline to post-intervention (both p < 0.001; see Table 2). The mean fatigue score decreased from 64.52 ± 9.39 to 54.35 ± 12.81 in the PMR group, and from 65.87 ± 8.95 to 51.25 ± 8.07 in the PE group. Although the between-group difference in fatigue reduction favored the PE group (Δ = − 14.62 ± 7.21 vs. − 10.17 ± 14.42), this difference was not statistically significant (t (64) = − 1.57, p = 0.12, d = 0.39).

Laboratory parameters

As detailed in Table 3, there were no statistically significant between-group differences in laboratory parameters, including hemoglobin (t(64) = 0.93, p = 0.36), hematocrit (t(64) = 0.96, p = 0.34), creatinine (t(64) = − 0.43, p = 0.67), urea (pre: t(64) = 1.05, p = 0.29; post: t(64) = 1.25, p = 0.21), or blood calcium (t(64) = 0.96, p = 0.58). Although not statistically significant (p = 0.07), the reduction in creatinine levels was greater in the PE group (− 0.31 ± 0.44 mg/dL) compared with the PMR group (− 0.11 ± 0.57 mg/dL), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Influence of demographic and clinical variables

Post-hoc analysis revealed that employment status (p = 0.03) and the number of hemodialysis sessions per week (p = 0.01) had significant independent effects on the total well-being score following intervention. Additionally, participants with autoimmune conditions had significantly higher fatigue scores (p = 0.01). No other demographic or clinical variables demonstrated significant effects on the primary outcomes.

Discussion

Research investigating the impact of various complementary techniques, including PMR, PE, and massage, on overall mental well-being scores has consistently demonstrated an increase in these ratings9,18. Additionally, our study revealed that both PMR and PE have the potential to improve overall mental well-being scores among patients receiving hemodialysis. However, it is noteworthy that the PMR group demonstrated a considerably higher average total mental well-being score than the PE group. Additionally, the results revealed a significant increase in the average total mental well-being score during the post-intervention period compared to the pre-intervention period in both groups.

In this regard, Wei et al. (2020) conducted a study to examine the impact of various sports on the mental well-being and sleep quality of elderly women. The findings demonstrated that physical activity has the potential to enhance the mental well-being and sleep quality of the population. It is worth noting that they suggest that stretching activities have a more significant impact on mental well-being than aerobic activities. The exercises were conducted daily for 16 weeks, with each session lasting one hour19. The findings of the study align with those of our research. It was suggested to engage in physical activity consistently in both studies. However, our study included four sessions per week, whereas the other study included six. The alignment between the two studies can be attributed to the similar number of sessions and the incorporation of stretching exercises, which are common to both.

In a further study conducted by Shang et al. (2021), the results obtained further demonstrated a direct correlation between mental well-being and physical exercise, as well as the role of physical exercise in enhancing well-being20. In contrast, the study conducted by Moriyama et al. (2020) aimed to examine the impact of group exercise intervention on the mental well-being and health-related QOL of the Japanese population. Remarkably, the findings did not demonstrate a significant influence of group exercise on the mental well-being of individuals21. However, Moriyama et al.’s study was limited by the inadequate representation of age and gender, as well as the inclusion of individuals who were either unwilling or inconsistent in their exercise habits. Consequently, the two groups examined were not completely equivalent. Consequently, these disparities may have confounded the well-being factor. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the study’s methodology involved conducting exercise sessions in a group setting, which poses challenges in controlling variables that may influence non-exercise-related characteristics. These constraints were identified in the described research and can be attributed as the causes for the observed inconsistencies.

On the other hand, Forbes et al. (2017) conducted a study examining the impact of exercise and relaxation on health and well-being. Their findings contradicted our study, suggesting that exercise is more efficacious than PMR22. It is worth noting that the previous study evaluated overall well-being, whereas the current study specifically examined participants’ mental well-being. Additionally, disparities in measurement instruments and variables may be a crucial factor contributing to the divergence in results. Furthermore, it is essential to note that the composition of the investigation mentioned above and its approach to execution differ from our study. In addition, previous research primarily presents the outcomes of comparing two investigations, highlighting the potential challenges of controlling intervening factors and ensuring equal conditions across the two experiments. These challenges may lead to calculation errors.

Furthermore, multiple studies have demonstrated that patients receiving hemodialysis not only suffer from mood disorders, insomnia, loss of work, and sadness but also endure a gradual onset of fatigue that can significantly impact their overall well-being and QOF23. Our research findings indicate that the practice of PMR may increase patients’ fatigue levels. PRE has been shown to decrease pain and fatigue and enhance QOF in numerous studies that are parallel to ours24,25,26,27,28. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated that both PMR and PE procedures have reduced pain and fatigue and improved QOF, not only among patients receiving hemodialysis but also among patients with various medical conditions, including those with cancer. In a 2021 study conducted by Cohen et al., the objective was to investigate the impact of exercise and relaxation training on fatigue in patients with breast cancer. The findings revealed that both PE and PMR techniques had a notable effect in reducing fatigue among patients. While this study did not find a significant difference in the efficacy of the two approaches, it suggests that both procedures are equally effective in alleviating fatigue among the patients under investigation29.

The results of these studies suggest that patients in various inpatient communities, such as individuals undergoing HD, experience fatigue and a decline in overall well-being due to the treatment and disease process. In addition, the demographic data analysis of this study revealed that underlying diseases, such as autoimmune conditions, can exacerbate the severity of these consequences and the level of fatigue. Consequently, addressing these complications is seen as a psychological and physical necessity for patients, potentially enhancing their acceptance of interventions and ensuring their consistent implementation. This, in turn, can lead to improved disease symptoms, which may explain the lack of significant differences between the two interventions. Hence, as a result of diligent monitoring and frequent interventions, patients in both groups will receive nearly identical ratings for improving their health condition.

Overall, our study found that none of the strategies mentioned earlier demonstrated a substantial advantage over the other methods in alleviating fatigue among patients receiving hemodialysis. Therefore, it is advisable to employ two techniques for patients receiving hemodialysis, taking into account their abilities and limitations. Nevertheless, further comprehensive research is still required in this domain.

Limitation

This study has limitations. The lack of an untreated control group prevents definitive causal conclusions, though this was an ethical decision to provide active therapy to all participants. Although individual randomization was employed, practical constraints, such as dialysis schedules, may have introduced bias. Additionally, although adherence was monitored, the precision of home exercise technique and unmeasured physical activity remain potential confounding factors.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both PMR and physical exercises have a substantial positive impact on the QOF, mental well-being, and fatigue levels of patients receiving hemodialysis. Consequently, the application of these techniques ensures comprehensive improvement in patients’ well-being by addressing both psychological and physical challenges. However, since there is no clear superiority of one method over the other in terms of average fatigue reduction in patients, and PMR is more effective in enhancing mental well-being, it is advisable to recommend PMR to patients receiving hemodialysis due to its ease of implementation and fewer limitations compared to physical exercises. Nevertheless, current research is promoting the development of comprehensive rehabilitation programs that integrate these approaches for broader clinical use and, ultimately, enhance patients’ overall QOF.

Data availability

The datasets generated in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HD:

-

Hemodialysis

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- PMR:

-

Progressive muscle relaxation

- PE:

-

Physical exercises

References

Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G. National Kidney Foundationpractice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Annals of internal medicine. 139 (2), 137–47. (2003).

Mousavi, S. S., Soleimani, A. & Mousavi, M. B. Epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in Iran: a review article. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 25(3), 697–702 (2014).

Borg, R., Carlson, N., Søndergaard, J. & Persson, F. The growing challenge of chronic kidney disease: An overview of current knowledge. Int. J. Nephrol. 2023, 9609266 (2023).

Yonata, A., Islamy, N., Taruna, A. & Pura, L. Factors Affecting quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Gen. Med 15, 7173–7178 (2022).

Aljawadi, M. H. et al. Quality of life tools among patients on dialysis: A systematic review. Saudi Pharm. J. 32(3), 101958 (2024).

Koyanagi, A. et al. Chronic conditions and sleep problems among adults aged 50 years or over in nine countries: A multi-country study. PLoS ONE 9(12), e114742 (2014).

Siebern, A. T., Suh, S. & Nowakowski, S. Non-pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Neurotherapeutics 9(4), 717–727 (2012).

Lu, Y., Wang, Y. & Lu, Q. Effects of exercise on muscle fitness in dialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Nephrol. 50(4), 291–302 (2019).

Toussaint, L. et al. Effectiveness of Progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing, and guided imagery in promoting psychological and physiological states of relaxation. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2021, 5924040 (2021).

Burckhardt, C. S. & Anderson, K. L. The quality of life scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity, and utilization. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 1, 60 (2003).

Smets, E. M., Garssen, B., Bonke, B. & De Haes, J. C. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 39(3), 315–325 (1995).

Pai, M. F. et al. Sleep disturbance in chronic hemodialysis patients: the impact of depression and anemia. Ren. Fail. 29(6), 673–677 (2007).

Smets, E. & Garssen, B. Bonke Bd, De Haes J: The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 39(3), 315–325 (1995).

Hafezi, S., Zare, H., Mehri, S. N., Mahmoodi, H. The multidimensional fatigue inventory validation and fatigue assessment in Iranian distance education students. In 2010 4th International Conference on Distance Learning and Educatio. 2010, 195–198, IEEE, 2010.

Keyes, C. L., Shmotkin, D. & Ryff, C. D. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82(6), 1007 (2002).

Kord, B. The prediction of subjective well-being based on meaning of life and mindfulness among cardiovascular patients. Iran. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 5(6), 16–23 (2018).

Mirzaei, P. Build mental well-being and to compare the effectiveness of this program with the program in reducing depression, happiness Fordyce high school students in Isfahan [dissertation] (Alzahra University, 2007).

Muhammad Khir, S. et al. Efficacy of Progressive muscle relaxation in adults for stress, anxiety, and depression: A systematic review. Psychol. Res Behav. Manag. 17, 345–365 (2024).

Wei-wei, Z., Jun-mei, X., Ling, Y. Influence of exercise prescription on subjective well-being and sleep quality of trailing elderly females. In E3S Web of Conferences (2020).

Shang, Y., Xie, H. D. & Yang, S. Y. The Relationship between physical exercise and subjective well-being in college students: The mediating effect of body image and self-esteem. Front Psychol. 12, 658935 (2021).

Moriyama, N., Omata, J., Sato, R., Okazaki, K. & Yasumura, S. Effectiveness of group exercise intervention on subjective well-being and health-related quality of life of older residents in restoration public housing after the great East Japan earthquake: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 46, 101630 (2020).

Forbes, H., Fichera, E., Rogers, A. & Sutton, M. The effects of exercise and relaxation on health and wellbeing. Health Econ. 26(12), e67–e80 (2017).

Kaplan Serin, E., Ovayolu, N. & Ovayolu, Ö. The effect of progressive relaxation exercises on pain, fatigue, and quality of life in dialysis patients. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 34(2), 121–128 (2020).

Khazaei Ghozhdi, M., Ghaljeh, M. & Khazaei, N. The Effect of progressive muscle relaxation technique on fatigue, pain and quality of life in dialysis patients: A clinical trial study. Evid. Based Care 12(4), 7–16 (2023).

Hadadian, F. et al. Studying the effect of progressive muscle relaxation technique on fatigue in hemodialysis patients – Kermanshah- Iran. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 11, 8 (2018).

Maniam, R. et al. Preliminary study of an exercise programme for reducing fatigue and improving sleep among long-term haemodialysis patients. Singapore Med. J. 55(9), 476–482 (2014).

Chou, H. Y., Chen, S. C., Yen, T. H. & Han, H. M. Effect of a virtual reality-based exercise program on fatigue in hospitalized Taiwanese end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clin. Nurs. Res. 29(6), 368–374 (2020).

Meléndez-Oliva, E. et al. Effect of a virtual reality exercise on patients undergoing haemodialysis: A randomised controlled clinical trial research protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(5), 4116 (2023).

Cohen, J., Rogers, W. A., Petruzzello, S., Trinh, L. & Mullen, S. P. Acute effects of aerobic exercise and relaxation training on fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A feasibility trial. Psychooncology 30(2), 252–259 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the patients who contributed to this research

Funding

This study was under the financial aegis of the Research Deputy of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Study design: MR H, TP, SV; data collection and analysis: M H, AA; manuscript preparation: M H, Kh M, MA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.NURSE.REC. 991513) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki; informed consent has been obtained from the subjects. The study purpose and importance were explained to participants who met the inclusion criteria, and they signed the written informed consent form. Patients were informed that they are free to leave the study at any time without affecting their treatment plan, should they wish to do so. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, which are aligned with the Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasanzadeh, M., Miri, K., Pourghaznein, T. et al. The Effect of progressive muscle relaxation and physical exercises on subjective well-being and fatigue of patients receiving hemodialysis: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 15, 43440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27302-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27302-4