Abstract

HT-9, a ferritic-Martensitic steel, has attracted significant interest as a structural and cladding material for a variety of high dose nuclear component applications. This study examines the tensile properties of a HT-9 fuel assembly duct from the fast flux test facility, FFTF. The duct, from the Advanced Core Oxide-3 (ACO-3) irradiation test, was subjected to fast neutron irradiation exposure ranging from 3 dpa above the core top to nearly 155 dpa near the core mid-plane, spanning a temperature range from 382 °C at the lower end to 504 °C at the top. Due to the combination of thermal and neutron flux gradients along the core height. This yields a variety of irradiation damage processes which depend on core location. Tensile properties of specimens extracted at different positions along the height of the irradiated duct were measured at 25 °C, 200 °C and near their in-core irradiation temperature. The results show temperature has a greater impact than dose on post-irradiation strength and ductility. Two irradiation temperature regimes were determined, below irradiation temperatures of 420 °C irradiation hardening increases as irradiation temperature decreases, and above that temperature relatively minor changes are observed in tensile properties. These results are discussed in terms of expected microstructural changes, indicating that dislocation content is a strong contributor in these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HT-9 has been selected as the primary material for use as clad and duct components of a number of advanced reactor designs due to its lower swelling and higher thermal conductivity compared to Austenitic stainless steels while having sufficient high temperature strength and compatibility with sodium cooled fast reactor coolant. HT-9 has also been successfully demonstrated in the experimental sodium cooled fast reactors EBR-II and FFTF in the United States1. Although initial results on HT-9 are promising, additional data are needed to provide a sufficient database for design of advanced reactor concepts with higher fuel utilization and therefore better economics. Of specific interest is the effect of irradiation temperature and dose on mechanical properties as that is important to the fuel design basis2.

During the final years of operation of the FFTF, many of the high dose fuel subassemblies, originally made of Austenitic stainless steels, were replaced with the ferritic/Martensitic steel, HT-9. One of these fuel subassemblies was contained in the ACO-3 duct, which was saved for analysis after FFTF shut down. This duct experienced a peak dose of 155 dpa. Material samples from this duct have been the subject of a wide variety of experimental studies to characterize the microstructural evolution due to the irradiation exposure3,4,5,6 and the influence of the irradiation exposure on mechanical properties7,8,9,10,11. In addition to the extensive examination of the ACO-3 duct material, HT-9 has been and continues to be the subject of many other irradiation studies over the past 30 plus years due to its superior irradiation damage tolerance combined with its appealing mechanical properties, particularly at elevated temperatures.

In the following, the results of tensile mechanical testing of samples from the ACO-3 duct are reported. These tensile experiments were performed on samples from a variety of irradiation dose - temperature pairs along the height of the ACO-3 duct as well as control specimens from the same alloy heat. These tensile tests were carried out at room temperature and 200 °C in all cases, and at tensile test temperatures which approximated the local irradiation temperature for the sample position along the length of the duct. Tensile strain-rate sensitivity was also examined by varying the strain rate by one order of magnitude during tensile loading at room temperature and for one selected condition at elevated temperature.

Experimental procedures

Materials

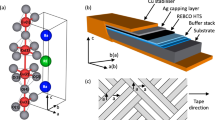

Extensive background on the history and irradiation conditions of the ACO-3 duct experiments and HT-9 heat can be found in Sencer et al.3. Specimens for tensile testing were EDM-machined from the duct, shown in Fig. 1. The measured composition of the duct material is listed in Table 1. Prior to irradiation, the duct received a heat treatment of a 30 min hold at 1065 ˚C followed by an air cool, then a 60 min hold at 750 ˚C followed by a final air cool4,6. Elemental analysis was performed for the control material which showed some differences as shown in Table 1. The control material received the same heat treatment. Samples for tensile testing were removed from the duct from locations 5E1, 2E1, 4E1, 6E1, 6E5 and 6E9, with specific dose and irradiation temperature given in Table 2. Samples will be referred to by their irradiation temperature and dose in this manuscript.

Sample fabrication

Subsized flat tensile specimens were machined from the duct and control material using electrical discharge machining (EDM). Samples, as shown in Fig. 2, were initially profiled into blanks at the full thickness (3 mm) of the duct, and then each blank was machined into three samples of roughly 0.75 mm thick. The sample gauge width was 1.2 mm and the gauge length was 5 mm. Exact measurements were recorded on each individual sample prior to testing. Samples were cut with their axes parallel to the extrusion direction (duct centerline) unless otherwise noted.

Testing conditions

Samples were tested on a 30 kN capacity Instron 5567 screw driven load frame located in the LANL CMR Wing 9 hot cell facility. The load frame was outfitted with an inert atmosphere furnace operable to 700 °C. Samples were loaded using manipulators into a set of ball ended grips in an alignment fixture (Fig. 3). Tests were performed at a constant cross head velocity of 0.15 mm/minute corresponding to a nominal engineering strain rate of 5 × 10− 4/sec. Load/displacement data were converted to engineering stress/strain data using the initial measured specimen dimensions. The compliance from the test system was mathematically removed from each curve. Elevated temperature tests took place under an ultra-high purity argon flush. Additional strain rate jump tests were performed with rates of 1 × 10− 3 and 1 × 10− 4 s− 1. Test conditions are presented in Table 3.

Results

Tensile behavior

Figure 4 shows the results for the control specimens as a function of testing temperature. The general tensile behavior indicates a drop in yield strength with temperature gradually from a high of 592 MPa at room temperature to 450 MPa for samples tested at 500 °C. Uniform elongation drops steadily with temperature from 8.75% at room temperature to 4.15% at 500 °C. Total elongation drops with temperature up to 450 °C. At 500 °C, it begins to increase.

Figure 5 displays the engineering stress-strain curves for tests on the irradiated samples aligned with the extrusion direction of the duct. Each extraction location, corresponding to a distinct irradiation dose and temperature, is represented in Fig. 5. Each irradiation condition had samples tested at three different temperatures as indicated in the plots. As the irradiation temperature decreased, irradiation hardening increased, with increases in yield strength and ultimate tensile strength, decrease in work hardening and a decrease in uniform and total elongation despite differences in dose levels. The averages of the tensile properties measurements from two or more tests are provided in Table 4.

Tensile rate jump behavior

In addition to the tensile tests performed at a fixed extension rate of 5 × 10− 4 s− 1, rate jump experiments were performed at rates of 1 × 10− 4 and 1 × 10− 3 s− 1 to provide information on the strain rate sensitivity of the irradiated samples. The irradiated samples were from each of the six locations from the ACO-3 duct. The summary of all the data can be seen in Fig. 6. Sample to sample variation and small differences in compliance prevents the direct overlay of data, but the general trends are consistent. The irradiated material at room temperature appears to have strain rate sensitivity, m, between 0.0045 and 0.0081. The strain rate sensitivity value increased with increasing irradiation temperature.

Rate jump experiments were performed at 350 °C for samples from the material irradiated at 382 °C to 22 dpa and an unirradiated control specimen out of the INL heat of HT-9. Information on the control material heat can be found in Maloy et al.12. The purpose of the tests at this temperature were to view whether there was inverse strain rate sensitivity via the Portevin-Le Chatelier (PLC) effect. Elevated temperature tests can display the PLC effect due to increased strain rates providing activation energy for dislocations to break free of solute clustering. Results of these experiments are presented in Fig. 7. For the irradiated sample there is some indication of serrations in the stress-strain curve at 10− 4 s− 1, these are on the order of 0.5 MPa. For the INL heat HT-9 that had not been irradiated, serrations were also observed on the order of 0.5 MPa only at 10− 4 s− 1 in the stress-strain curve. The strain rate sensitivity for the irradiated specimen tested at 350 °C was − 0.0010.

Discussion

General tensile response

Irradiation dose and temperature result in changes to the mechanical behavior of this alloy. Figure 8 shows yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, uniform elongation and total elongation as a function of irradiation temperature. Figure 9 shows the impact of irradiation dose on these same properties. From the results it appears irradiation temperature has an impact on mechanical properties while the irradiation dose does not have as significant of an impact in these irradiation conditions. The relationship of these properties to the irradiation-induced microstructural changes will be discussed further below. There are a few observations that can be made based on the tensile data:

-

1.

Yield strength and ultimate tensile strength increase with decreasing irradiation temperatures below 420 °C. For uniform and total elongation, both decrease with decreasing irradiation temperature below 466 °C.

-

2.

The mechanical properties dependence on irradiation dose is far less dramatic than of irradiation temperatures, highlighted by the lowest irradiation temperature of 382 °C at 22 dpa having a 55% higher strength than the sample irradiated at 441 °C to 147 dpa.

-

3.

For all conditions irradiated above 440 °C, tensile yield and ultimate strengths were similar in value, but slightly lower, to the unirradiated control material.

-

4.

These trends were similarly observed for the different tensile test temperatures, from 25 °C to tests performed approximately at the irradiation temperature.

These trends in tensile strength are consistent with a previous study of shear punch tested samples irradiated in BOR-60 of the same heat of HT-913. An irradiation temperature of 430 °C still showed significant hardening while the shear punch results were nearly the same as the control material at irradiation temperatures of 460 °C and 520 °C. Consistent again, Lechtenberg analyzed data on ferritic steels irradiated in EBR-II and HFIR reactors and found irradiation hardening starts to decrease above around 400 °C with strength near the control material at an irradiation temperature around 500 °C14. That study, however, did not have results between 100 °C and 400 °C to also compare.

Role of irradiation-induced microstructure

The tensile testing results presented show a connection between irradiation temperature and the strength and elongation. Correlating to microstructure from previous studies is instructive to understand why. The primary feature types that change during irradiation are the dislocations and precipitates, which will be described. This section will first describe estimated strengthening from the dispersed barrier hardening model (DBH) separately for precipitates and dislocations. Then some specific considerations based on precipitate spatial distribution and dislocation character which are not considered in a DBH analysis. Strengthening is primarily expected from changes to dislocation content while there is a secondary contribution from precipitates. Each of these contributions is dependent on irradiation temperature.

Extensive studies have been performed characterizing the microstructure of the neutron irradiated ACO-3 duct material and other neutron irradiated samples of HT-93,4,15,16,17. Some representative microstructural quantifications of the ACO-3 duct material from previous studies are shown in Table 5. The data presented in Table 5 is a compilation of representative microstructural data from the studies referenced above. Microstructural data are available for only limited exposure conditions for the material conditions in the present study.

These data are useful regarding their influence as potential strengthening mechanisms resulting in the observed tensile behavior. It is understood that irradiation induced features including dislocation loops and precipitates contribute to strengthening of the material by acting as barriers to dislocation slip, typically quantified in a dispersed barrier hardening (DBH) model18,19,20,21. Other strengthening factors in HT-9 are relatively constant before and after irradiation, including the hierarchical grain structure including laths organized into packets into prior austenite grains, and solid solution strengthening. The DBH model has shown good agreement in irradiated metals and is the predominant mechanism used for calculating strengthening due to irradiation induced defects.

For this alloy system, there are two notable precipitate types that form during irradiation, the G and α’ phases. The α’ phase is a Cr-rich Fe-Cr phase that forms in the lower irradiation temperatures in this study4,20, with nearly the same lattice parameter and a higher elastic modulus that will increase dislocation line energy compared to the ferrite matrix. It is typically considered to have a relatively small influence on strengthening, but in sufficiently high number densities, its effect is notable. The G phase, a Mn-Ni-Si rich phase, is another commonly observed precipitate and found over a similar temperature range as the α’ phase in the present studies. The G phase precipitates have been observed to be heterogeneously distributed, with preference to lath boundaries4,20, which will also decrease the strengthening effect compared to DBH model predictions. It has a FCC crystal structure and significantly larger lattice parameter than the ferritic matrix. It also appears to have a relatively weak effect on barrier strengthening20. The introduction of these two phases will cause strengthening and can be represented in the DBH model with uniform spatial distribution of obstacles in the matrix as follows:

Dislocation content changes with irradiation, including the introduction of dislocation loops at the irradiation temperatures up to 450 °C. An increase is also observed in lattice dislocation density at irradiation temperatures of 375 and 415 °C. The loop structures are retained to higher doses for conditions at the lower irradiation temperatures. No dislocation loops or changes to the lattice dislocation content were observed at irradiation temperatures of 470 and 504 °C. The overall contribution of the dislocation loop and line content in the DBH uniform spatial distribution of obstacles in the matrix is formulated as:

Taken together, the full impact on yield strength can be expressed several ways with somewhat similar results: by a linear sum, root sum of squares, or root sum square of weak and strong obstacles separated21. The quantitative result depends on the (i) the value of α which will vary based on how it was determined and (ii) accurate microstructural quantification. Below is the linear summation of the various microstructure-based hardening effects added to the innate materials yield strength, σ0:

In these relationships, previous studies have proposed the following constants: M, T, and Y. M, the Taylor constant is typically taken to be 3; µ, the shear modulus, is 86.95 GPa; b, the Burger’s vector, is 0.24466 nm. The suggested strength factors, α, are typically reduced from fitting analysis with typical values of αα’ ~ 0.1, αG ~ 0.15, αloops ~ 0.1 and αlines ~ 0.3. The choice of αlines ~ 0.3 is typical derived from an alloy condition where most or all of the strengthening is derived solely from the dislocation contribution. In this case, the 2E1 condition at 2 dpa and 501 °C is the best selection for fitting. In this case, αlines ~ 0.6, is more appropriate. It should be noted that the dislocation densities (see Table 5) were derived from neutron or synchrotron scattering experiments using a line broadening technique. This approach includes all scattering contributions regardless of the state of the dislocation mobility, that is, entwined in lath or PAG boundaries or as mobile dislocation structures.

The relative contributions from the various strengthening mechanisms are shown in Table 6; note that some microstructural data are not available for certain irradiation conditions (see Table 5). The values are shown visually in the chart in Fig. 10. From the DBH analysis, strength is mostly from lattice dislocations. At the 375 °C irradiation temperature there is also a significant component from alpha prime and G-phase precipitates.

It has been proposed20 that the irradiation-induced strengthening is largely, nearly totally, due to the dislocation density since the correlation between the square root of the dislocation density, Δσ α √, correlates to a very high degree with the measured yield strengths. Further support for this conclusion is provided in a recent 3D microstructural analysis20 which shows that the major concentrations of carbides, α’ and G phases are not uniformly distributed in the matrix, but rather distributed to a high degree in lath and other boundaries. Co-location of the irradiation induced precipitates at grain and lath boundaries that are existing barriers to dislocations will limit their impact on yield strength from plastic deformation occurring in the lath interiors. Plastic deformation occurring along the lath or prior austenite grain boundaries would be impacted by the precipitates distributed preferentially on the boundaries. It is unknown the exact impact of the precipitates on the yield strength.

Other observations stem from the differences in the yield strength of the irradiated material compared to the unirradiated control material. The 2E1 2 dpa at 504 °C condition, the 5E1 147 dpa at 441 °C and the control condition have similar dislocation densities, but the control condition has a considerably lower yield strength. This is likely due to differences in the mobile versus fixed dislocation fractions. A previous neutron and x-ray diffraction study show5 that there is a notable change in the dislocation nature due to irradiation which results in a large edge dislocation fraction at lower irradiation temperatures. This is a transformation from a nearly total screw dislocation population in the control conditions. This provides evidence that substantial dislocation restructuring takes place during irradiation. Thus, it is not surprising that despite nearly equivalent dislocation populations, the control specimen has distinctly different and lower yield properties. This lower level of pre-irradiation yield strength has been attributed to the relatively high temperature tempering treatment of the material for the ACO-3 duct material.

The irradiation condition 4E1, 93 dpa at 466 °C shows a notable degree of softening compared to either the control condition or the 2E1, 2 dpa at 504 °C condition despite exposure to a high irradiation dose. This condition is at a sufficiently high temperature that neither the α’ or the G phases are found and any initial dislocation loop development would have grown into line segments at this temperature. Some indication of small amounts of void formation are reported. The only observable features relating to strengthening, again measured by neutron and x-ray scattering techniques, are the dislocation density and M23C6 fraction. The dislocation density is at a lower level than any of the other conditions, including the control condition in this study, indicating that substantial amounts of dislocation recovery has taken place. The carbide fraction is nearly the same as the original carbide fractions, however, possibly with a different distribution which could impact the yield strength by either increasing or decreasing depending on the how the distribution changed. Taken together, these two factors could account for the relatively low yield strength of that particular irradiation condition.

Finally, while the irradiation temperature appears to be much more important to material irradiation response than the dose level, the correlation between the dislocation structures and the yield properties indicate that the irradiation doses, even at marginal levels do play an important role restructuring the dislocation types and arrangements. Due to the large differences in total doses, it also appears that this restructuring is stable once formed despite very high atomic displacement levels in some cases.

Rate jump test response and strain rate sensitivity

Rate jump experiments were performed at room temperature for all locations from the irradiated duct by varying the strain rates between 1 × 10− 4s− 1 and 1 × 10− 3s− 1. Elevated temperature tests took place at 350 °C on irradiated material from location 6E9 with a dose of 22 dpa at 382 °C. Rate sensitivity was calculated in all cases. The sensitivity varied with irradiation condition, but the differences were not extreme. There was negative rate sensitivity in the 350 °C tests in addition to serrations in the stress-strain curves at 10− 4 s1, suggesting PLC, but further work must be done to explore this effect more clearly.

Strain rate sensitivity, m, was calculated for each sample based on the formula22:

With έ1 and έ2 being the slower (1 × 10−4s−1) and faster (1 × 10‐3s−1) strain rates, respectively, and σ1 and σ2 being the stresses measured just before and after the strain rate jump.

Table 7 shows the calculated strain rate sensitivity for the rate jump experiments performed. Values for m have an error of roughly +/- 0.0005 for room temperature tests, based on consistency between tests and in different jumps in the same experiment. The elevated temperature experiments have more uncertainty due to larger time for the tests to equilibrate between rate jumps.

Based on the observation that the irradiation-induced dislocation structure and dislocation type evolution is the most important component of the irradiation strengthening, it is possible to assess the role of the dislocation structure on the observed rate jump behavior. It is well established23,24 that the movement of the screw component of the dislocation population is the rate controlling factor in deformation in bcc metals and alloys. As noted, neutron scattering observations have been presented to show that the screw component in the various ACO-3 locations is directly affected by the irradiation exposure. At the lowest irradiation temperature, the screw component is only about 45% of the total, despite the control material having around 95% screw component. The high level of screw component in the control has been attributed to the post-extrusion heat treatment which was performed at a sufficiently high temperature to allow edge components to climb out of the structure. The irradiation-induced dislocation imparts a strong addition to the edge population at lower temperatures, but likely due to thermal effects, the screw population component grows as a fraction of the total as the irradiation temperature increases.

The rate controlling mechanism based on the screw dislocation segments is related to the thermally-activated generation of edge kinks on the screw dislocation lines. These edge kinks can travel quickly once formed accounting for the movement of the screw segments. Thus, the partition between the edge and screw components should help to account for the differences observed in the strain rate sensitivity constant, m, in the jump rate tests (see Table 7). The screw dislocation fractions for these particular ACO-3 duct irradiation conditions, measured using neutron diffraction techniques5 can be compared with the observed m values as shown in Fig. 11.

It should be noted that the strain rate sensitivity data are for conditions just past yield while the screw dislocation measurements were made on undeformed specimens. Nevertheless, since the measurements were made near the yield point at room temperature, the fractions of the two dislocation components should be representative of the structures at small plastic strains. It is notable that the lowest strain rate sensitivity is associated with the largest fraction of edge dislocations in the structure. This would be expected due to the easier mobility of the edge components. At the highest irradiation temperature, the screw component is nearly 100% of the total, again correlating with the highest strain rate sensitivity.

The set of elevated temperature, 350 °C, strain rate sensitivity tests was performed on the ACO-3 duct material irradiated to 22 dpa at 382 °C. As noted above, the screw dislocation fraction was 45%. The negative value is an indication of the PLC effect where clouds of free interstitials require a higher stress to release dislocations for slip and, depending on temperature and strain rate, intermittently follow and re-pin the dislocations during the slip process. Similar negative strain rate sensitivity constants due to dynamic strain aging (DSA) have been observed in HT-925 and in 9Cr-1Mo F/M alloys26,27. The results presented here are consistent with the study by Sarkar et al. The amplitude of the serrations in the stress-strain curves are an order of magnitude smaller in this study, possibly due to either unknown differences in material or experimental uncertainty that could include insufficiently small acquisition time between stress and strain measurements. For the 9Cr-1Mo alloys, DSA is observed in a temperature range between about 200 °C to 350 °C at strain rates between 5 × 10− 6/s to 10− 3/s, depending on the range of experimental conditions in those studies. The conditions in the present work are at the upper end of the temperature range and within the bounds of the strain ranges indicating a comparable DSA process to the 9Cr-1Mo system.

Recent detailed dislocation dynamics experimental studies in Fe-based alloy systems provide some direct insights into DSA processes in the Fe-Cr system. In all cases, the mobility of the screw dislocations are the rate controlling feature. For the Fe-Cr system with even modest amounts of carbon, the results show that Cr-C complexes tend to remove carbon as an active free interstitial element leaving diffusion of excess, substitutional Cr as the likely interacting element which would restrict DSA interactions to higher temperatures due to the much higher diffusion activation energy of Cr, also consistent with the Leslie’s proposed mechanism28. The alternative to either carbon or chromium is the interaction with nitrogen, which is the proposed DSA mechanism supported by Verma et al.29 which they found consistent with earlier studies. Verma et al. report an activation energy for the diffusion of nitrogen at 58 kJ/mole, which is lower than typical values for carbon at ~ 84 kJ/mol and much lower than the activation energy for the diffusion of chromium at ~ 250 kJ/mol. Recent studies on the role of nitrogen in the evolution of radiation damage in F/M alloys30,31 indicates that nitrogen plays a very active role in the development, and presumably, the movement, of dislocation structures in F/M alloys, though there is no direct evidence in the present study.

Post yield hardening response

There are a variety of modeling approaches to represent post-yield strain hardening in alloys. Here, the modified Johnson-Cook (MJC) approach is employed to characterize the initial portion of the post-yield hardening process and to model the influence of strain rate effects on the jump rate tests. The general form of the MJC model is given as:

where A, B, C and D are constants. A is typically proportional to the yield strength value, B and C represent the linear post yield hardening and D, the influence of strain rate). Note that a C represents a parabolic strain hardening superposed on a linear post-yield slope. Values for these constants were determined by the best fit to the measured tensile curves are provided in Tables 8 and 9.

The fitting results are based on the best fit to each condition. This accounts for the variation in the B, C and D constants. This approach is perhaps more useful for design considerations since the post-yield deformation is characterized as a best fit. Overall, the appropriateness of a post-yield hardening slope, A, which provides a linear strengthening contributions, modified by a negative parabolic contribution to account for the strengthening, and an additional modification, D, to account for strain rate sensitivity provide excellent characterization of the experimental post-yield tensile curves.

Summary

This work presents an extensive series of quasi-static tensile tests on irradiated HT-9 material, representing a variety of temperature and dose conditions across the ACO-3 duct irradiated in a fast neutron environment in the FFTF reactor. Data for yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, uniform elongation, and total elongation are presented for both control and irradiated material at a variety of testing temperatures. Tensile rate-jump tests were performed as well, allowing for calculation of a rate sensitivity parameter, m for various irradiation conditions. The following are key results from this study:

-

Yield strength and elongation correlate with irradiation temperature, rather than dose. Yield strength increases with decreasing irradiation temperature between 416 and 382 °C. Uniform and total elongation decrease with decreasing irradiation temperature at and below 466 °C. While at higher irradiation temperatures yield strength is comparable to that of the control samples.

-

Strain-rate sensitivity correlates with percentage of screw dislocations.

-

Modified Johnson-Cook post yielding hardening model parameters were determined for each of the test curves.

Data availability

Data is available upon request. Contact Tarik Saleh at the following email address tsaleh@lanl.gov.

References

Uwaba, T. et al. Irradiation performance of fast reactor MOX fuel pins in ferritic/martensitic cladding irradiated to high burnups. Journal Nuclear Materials, 412, (2011), 294-300.

Porter, D. L. & Crawford, D. C. Fuel performance design basis for the versatile test reactor. Nuclear Sci. Engineering, 196, (2022), 110-122.

Sencer, B. H., Kennedy, J. R., Cole, J. I., Maloy, S. A. & Garner, F. A. Microstructural analysis of an HT9 fuel assembly duct irradiated in FFTF to 155 Dpa at 443°C. Journal Nuclear Materials, 393, (2009), 235-241.

Anderoglu, O. et al. Phase stability of an HT-9 duct irradiated in FFTF. Journal Nuclear Materials, 430, (2012), 194-204.

Mosbrucker, P. L. et al. Neutron and x-ray diffraction analysis of the effect of irradiation dose and temperature on microstructure of irradiated HT-9 steel. Journal Nuclear Materials, 443, (2013), 522-530.

Tomchik, C. et al. High energy x-ray diffraction study of the relationship between the macroscopic mechanical properties and microstructure of irradiated HT-9 steel. Journal Nuclear Materials, 475, (2016), 46-56.

Byun, T. S., Lewis, W. D., Toloczko, M. B. & Maloy, S. A. Impact properties of irradiated HT9 from the fuel duct FFTF. Journal Nuclear Materials, 421, (2012), 104-111.

Byun, T. S., Toloczko, M. B., Saleh, T. A. & Maloy, S. A. Irradiation dose and temperature dependence of fracture toughness in high dose HT9 steel from the fuel duct of FFTF. Journal Nuclear Materials, 432, (2013), 1-8.

Byun, T. S., Baek, J. H., Anderoglu, O., Maloy, S. A. & Toloczko, M. B. Thermal annealing recovery of fracture toughness in HT9 steel after irradiation to high doses. Journal Nuclear Materials, 446, (2014), 263-272.

Baek, J. H., Byun, T. S., Maloy, S. A. & Toloczko, M. B. Investigation of temperature dependence of fracture toughness in high-dose HT9 steel using small-specimen reuse technique. Journal Nuclear Materials, 444, (2014), 206-213.

Maloy, S. A., Toloczko, M., Cole, J. & Byun, T. S. Core materials development for the fuel cycle R&D program. Journal Nuclear Materials, 415, (2011), 302-305.

Maloy, S. A. et al. Characterization and comparative analysis of the tensile properties of five tempered martensitic steels and an oxide dispersion strengthened ferritic alloy irradiated at approximate to 295 degrees C to approximate to 6.5 Dpa. Journal Nuclear Materials, 468, (2016), 232-239.

Eftink, B. P. et al. Shear punch testing of neutron-irradiated HT-9 and 14YWT, JOM, 72, (2020), 1703-1709.

Lechtenberg, T. Irradiation effects in ferritic steels. Journal Nuclear Materials, 133, (1985), 149-155.

Zheng, C. et al. Microstructure response of ferritic/martensitic steel HT9 after neutron irradiation: effect of dose. Journal Nuclear Materials, 523, (2019), 421-433.

Zheng, C. et al. Microstructure response of ferritic/martensitic steel HT9 after neutron irradiation: effect of temperature. Journal Nuclear Materials, 528, (2020), 151845.

Field, K. G., Eftink, B. P., Parish, C. M. & Maloy, S. A. High-efficiency three-dimensional visualization of complex microstructures via multidimensional STEM acquisition and reconstruction. Microscopy Microanalysis, 26, (2020), 240-246.

Bergner, F., Pareige, C., Hernandez-Mayoral, M., Malerba, L. & Heintze, C. Application of a three-feature dispersed-barrier hardening model to neutron-irradiated Fe-Cr model alloys. Journal Nuclear Materials, 448, (2014), 96-102.

Bhattacharyya, D. et al. Microstructural changes and their effect on hardening in neutron irradiated Fe-Cr alloys. Journal Nuclear Materials, 519, (2019), 274-286.

Yan, H., Liu, X., He, L. & Stubbins, J. Phase stability and microstructural evolution in neutron-irradiated ferritic-martensitic steel HT9. Journal Nuclear Materials, 557, (2021), 153252.

Zhu, P., Zhao, Y., Lin, Y. R., Henry, J. & Zinkle, S. J. Defect-specific strength factors and superposition model for predicting strengthening of ion irradiated Fe18Cr alloy. Journal Nuclear Materials, 588, (2024), 154823.

Dieter, G. E. Mechanical Metallurgy, 3rd Edition, p. 297 (1986).

Christian, J. W. Some surprising features of the plastic deformation of body-centered cubic metals and alloys. Metallurgical Trans. A, 14, (1983), 1237-1256.

Monnet, G., Vincent, L. & Devincre, B. Dislocation-dynamics based crystal plasticity law for the low- and high- temperature deformation regimes of Bcc crystal. Acta Materialia, 61, (2013), 6178-6190.

Sarkar, A., Maloy, S. A. & Murty, K. L. Investigation of Portevin-Le Chatelier effect in HT-9 steel. Materials Sci. Engineering: A, 631, (2015), 120-125.

Marmy, P., Martin, J. L. & Victoria, M. Deformation mechanisms of a ferritic-martensitic steel between 290 and 870 K. Materials Sci. Engineering: A, 164, (1993), 159-163.

Murty, K. L. & Seok, C. S. Fracture in ferritic reactor steel-dynamic strain aging and Cyclic loading. JOM, 53, (2001), 23-26.

Leslie, W. C. Iron and its dilute substitutional solid solutions. Metallurgical Transactions, 3, (1972), 5-26.

Verma, P. et al. V., Dynamic strain ageing, deformation, and fracture behavior of modified 9Cr-1Mo steel. Materials Sci. Engineering: A, 621, (2015), 39-51.

Rietema, C. J. et al. The influence of nitrogen and nitrides on the structure and properties of proton irradiated ferritic/martensitic steel. Journal Nuclear Materials, 561, (2022), 153528.

Aydogan, E. et al. Nitrogen effects on radiation response in 12Cr ferritic/martensitic alloys. Scripta Materialia, 189, (2020), 145-150.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Nuclear Energy Advanced Fuels Campaign under DOE Idaho Operations Office. This work was performed in part at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Los Alamos National Laboratory is an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, and is operated by Triad National Security, LLC for the National Nuclear Security Administration of U.S. Department of Energy under contract no 89233218CNA000001. The U.S. Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes.

Funding

This work was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Nuclear Energy Advanced Fuels Campaign under DOE Idaho Operations Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tarik Saleh contributed to data acquisition, analysis, writing, funding acquisition, and conceptualization; Benjamin Eftink contributed to analysis, writing and funding acquisition; Tobias Romero contributed to data acquisition and analysis; Dominic Piedmont contributed to analysis and modeling; James Stubbins contributed to analysis, modeling and writing; Mychailo Toloczko contributed to conceptualization; and Stuart Maloy contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition and analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saleh, T.A., Eftink, B.P., Romero, T.J. et al. Tensile properties of the neutron irradiated HT-9 ACO-3 duct. Sci Rep 15, 43236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27323-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27323-z