Abstract

Remnant cholesterol (RC) serves as an important indicator for assessing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, however, correlation with contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) remains unclear. This research investigated the relationship between RC and the occurrence of CI-AKI in STEMI patients following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). A cohort of 1288 patients with STEMI undergoing PCI were enrolled and stratified into CI-AKI and non-CI-AKI groups based on standard diagnostic criteria. Independent risk factors for CI-AKI were identified using Boruta analysis and logistic regression. The association between RC and CI-AKI was evaluated for nonlinearity using restricted cubic splines (RCS). The predictive performance of RC for identifying CI-AKI was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, while its incremental value to an existing risk model was determined by the net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination index (IDI). The ROC analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) for predicting CI-AKI based on blood urea nitrogen, left ventricular ejection fraction, and fasting plasma glucose was 0.739 (95% CI 0.703–0.775, P < 0.001), while the AUC increased to 0.803 (95% CI 0.772–0.834, P < 0.001) when RC was integrated into the model. Additionally, the NRI (0.618, 95% CI 0.470–0.766, P < 0.001) and the IDI (0.053, 95% CI 0.036–0.076, P < 0.001) both highlight improved prediction performance. RC is an independent predictor of CI-AKI in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI. The inclusion of RC significantly enhances the predictive accuracy of a model based on established clinical parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) refers to acute renal impairment resulting from the administration of contrast agents during angiography or other medical procedures1. It is now recognized as the third most common cause of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury, significantly increasing the risks of short- and long-term morbidity and mortality2,3. Since no definitive therapeutic strategies are currently available for CI-AKI, its pathogenesis is potentially modifiable, early identification of high-risk individuals and implementation of preventive measures are critically important4. The exact mechanisms underlying CI-AKI remain unclear, however, existing research highlights a strong association with inflammatory activation5,6,7.

Remnant cholesterol (RC) reflects the remnants of lipoproteins at various stages of triglyceride breakdown and conversion, representing the total cholesterol content within all triglyceride-enriched lipoproteins (TRLs)8. As an indicator of lipid metabolism abnormality, RC has been shown to induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and activate inflammatory signaling pathways, which are associated with cardiovascular diseases and renal dysfunction9,10,11.

Previous research has examined the relationship between traditional lipid markers, both total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG), and CI-AKI12,13,14. The association between RC and CI-AKI following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains unclear. This study therefore aims to investigate this association in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing PCI.

Methods

Subjects and research design

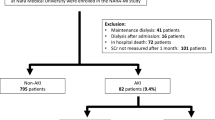

This retrospective analysis focuses on patients diagnosed with STEMI at admission who had complete medical records and underwent PCI treatment between January 2020 and December 2023. Their baseline and clinical characteristics were obtained from the electronic medical record system of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University. The study cohort was subsequently divided into CI-AKI and non-CI-AKI groups based on postoperative outcomes.

Exclusion Criteria: (1) Patients with incomplete clinical information; (2) Heart failure with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional status of Class III or higher; (3) Severe hepatic dysfunction; (4) Acute infections; (5) History of malignancies; (6) Use of other radiographic contrast agents or nephrotoxic substances—including but not limited to aminoglycoside antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin, amikacin, tobramycin), immunosuppressants with elevated or newly initiated trough concentrations (e.g., cyclosporine, tacrolimus), and nephrotoxic traditional/herbal medicines such as preparations containing aristolochic acid (Fig. 1).

Data acquisition and PCI protocol

Sample Testing: All blood specimens and laboratory indicators were tested and assessed in the central and clinical laboratories of Xuzhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed via echocardiography performed within 2 days of admission.

PCI Procedure: PCI procedures were carried out by skilled interventional cardiologists. Standard catheters, guidewires, balloons, and stents were used, with a radial artery approach in adherence to clinical guidelines. A non-ionic, low-osmolar contrast agent (iodixanol) was selected, and intravenous infusion of 0.9% saline at 1 mL/kg/h was administered for 12 h post-contrast use.

Definition of the indicators

(1) The 2019 European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines recommend RC was calculated using the formula RC = TC minus LDL-C and HDL-C15. (2) CI-AKI was defined as a ≥ 26.5 μmol/L increase in serum creatinine within 48 h after PCI, or a serum creatinine level ≥ 1.5 times baseline, or a urine output < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 consecutive hours16.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, based on their normal or non-normal distribution, and were compared using the independent samples *t*-test or Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and were compared using the chi-square test. Collinearity was first screened with Pearson correlation, retaining the clinically more relevant variable among correlated pairs, and multicollinearity was subsequently assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) after model construction. Independent risk factors for CI-AKI were identified using Boruta analysis followed by logistic regression. The dose–response relationship between RC and the probability of CI-AKI was analyzed using restricted cubic splines (RCS).The predictive performance of RC was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Furthermore, the incremental value of adding RC to an established CI-AKI risk model was quantified by calculating the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) and net reclassification improvement (NRI).All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1). Specific packages included: Boruta (v8.0.0) for feature selection, glm for logistic regression, rms (v6.7-0) for RCS modeling, pROC (v1.18.4) for ROC analysis, and PredictABEL (v1.2-5) for IDI/NRI calculations. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The incidence of CI-AKI after PCI was 15.1% (195/1288). A comparison of baseline characteristics between the CI-AKI and non-CI-AKI groups is presented in Table 1. Patients who developed CI-AKI were significantly older, more likely to be female, smokers, and to have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They also presented with a significantly higher resting heart rate, fasting plasma glucose, neutrophil count, and a greater prevalence of chronic kidney disease and higher Killip classification. Additionally, levels of D-dimer, red blood cell distribution width, glycosylated hemoglobin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, hs-CRP, hs-TnT, NT-proBNP, lactate dehydrogenase, and RC were higher in the CI-AKI group. However, the CI-AKI group had a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Risk factors for CI-AKI

The dependent variable was defined as whether CI-AKI occurred, with the 19 indicators serving as the independent variables. Feature selection was performed using the Boruta algorithm, a wrapper method built on a random forest ensemble.

It first augments the original feature set with “shadow features” created by permuting each real variable, trains a random forest on the combined set, and then compares the importance score of every real feature with the highest importance achieved by any shadow feature. Features whose importance consistently exceeds this “shadow maximum” are tagged “important”, those that repeatedly fall below are tagged “irrelevant”, and the remainder are marked “tentative”. The procedure iterates until all features are classified or a stopping limit is reached, producing an objective, threshold-free subset of variables that carry unique predictive information for the target. In the Boruta algorithm report, variables such as RC in the green zone are highlighted as significant contributors to the model. Those in the yellow zone are tentatively linked to potential adverse outcomes, whereas variables in the red zone are considered unimportant (Fig. 2). The Boruta algorithm identified total cholesterol (TC), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lymphocytes (LYM), NT-proBNP, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), eGFR, LVEF, and RC as important features for CI-AKI in STEMI patients undergoing PCI.

Importance of potential risk factors of contrast-induced acute kidney injury ranked by Boruta algorithm. The horizontal axis is the name of each variable, and the vertical axis is the Z value of each variable. The box plot shows the Z value of each variable during model calculation. The green boxes represent important variables, the red boxes represent unimportant variables, and the yellow boxes represent potentially important variables. Note T2DM, Type 2 diabetes mellitus; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; HR, Heart rate; RDW, Red cell distribution width; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; NEUT, Neutrophil; BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; LYM, Lymphocyte; FPG, Fasting plasma glucose; eGFR, Estimated glomerular filtration rate; TC, Total cholesterol; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RC, Remnant cholesterol; HbA1c, Glycated hemoglobin A1c.

Logistic regression analysis using the above factors revealed that BUN, FPG, LVEF, and RC are significant independent predictors of CI-AKI (Table 2). The variance inflation factor for all covariates in the final model ranged from 1.03 to 1.93, indicating no substantial multicollinearity.

Relationship between RC levels and CI-AKI

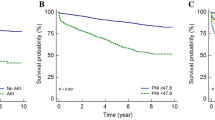

RCS analysis demonstrated a significant nonlinear association between RC and the risk of CI-AKI (P for overall < 0.001; P for nonlinear < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Using RC = 0.637 mmol/L as the reference point, the risk of CI-AKI was lower when RC levels were below the reference, while a gradual increase in CI-AKI risk was observed with higher RC levels. Notably, the odds ratio (OR) rose markedly when RC exceeded approximately 1.0 mmol/L, confirming that elevated RC is an independent risk factor for CI-AKI..

The receiver operating characteristic analysis

ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUC of BUN was 0.656, LVEF was 0.689, FPG was 0.646, and RC was 0.717 (P < 0.05). RC had a cutoff value of 0.47 ng/mL, which yielded a sensitivity of 77.4% and a specificity of 60.7%. (Table 3, Fig. 4).

Construct models

Informed by the outcomes of multivariable analysis, a traditional model including BUN, LVEF, and FPG was constructed. ROC analysis indicated that this traditional model had significant value for predicting CI-AKI, with an AUC of 0.739 (95% CI 0.703–0.775, P < 0.001).The incorporation of RC into this model significantly increased the predictive performance, yielding an AUC of 0.803, (95% CI 0.772–0.834, P < 0.001) (Table 4, Fig. 5).

Net reclassification index and integrated discrimination index

The incremental predictive value of adding RC to the baseline model was further quantified using the net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination index (IDI). These findings showed NRI was 0.618 (95% CI 0.470–0.766) and IDI was 0.053 (95% CI 0.036–0.076), both achieving statistical significance (P < 0.001). These findings confirm that the inclusion of RC significantly enhances the model’s ability to stratify risk for CI-AKI (Table 5).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that RC is an independent risk factor for CI-AKI in STEMI patients undergoing PCI, exhibiting a significant nonlinear dose–response relationship. Furthermore, incorporating RC into a clinical prediction model significantly enhanced its discriminatory power for CI-AKI. These findings align with contemporary research establishing elevated RC as a significant residual risk factor for adverse outcomes in STEMI patients17,18,19. For instance, the ACCORD trial prospectively demonstrated that each standard deviation increase in RC was associated with an approximately 7% higher risk of cardiovascular events20. The pathophysiological link between lipids and renal injury has long been hypothesized, notably by Moorhead et al.’s “lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis”, which implicated aberrant lipid metabolism in glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage21. Our results provide compelling clinical evidence supporting this mechanistic link in the context of CI-AKI.

Inflammation is a well-established critical driver in the pathogenesis of CI-AKI, and specific inflammatory markers can predict its occurrence in ACS patients following PCI10,11,22. A Mendelian randomization study confirmed the causal association between RC and inflammation, suggesting that RC may contribute to CI-AKI through inflammation-mediated pathways9. The non-linear relationship observed in our RCS analysis also indicates that RC is a modifiable target. Recent studies suggest that RC can infiltrate arterial walls, causing localized microvascular lesions: (1) Inflammatory Activation and Atherogenesis: RC lipoproteins infiltrate arterial walls and are taken up by macrophages, forming foam cells. This process activates PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling, inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and exacerbating vascular inflammation and oxidative stress. RC further amplifies this cascade by modulating oxidized LDL and NF-κB-dependent receptors, promoting atherosclerosis and renal ischemia23,24,25.(2) Pro-thrombotic Effects: In the hypercoagulable state of STEMI, RC upregulates PAI-1 to enhance platelet aggregation and amplifies the coagulation cascade, thereby reducing renal perfusion and increasing hypoxia26,27,28.(3) Impaired Renal Repair: The pre-existing renal vulnerability from elevated RC is compounded by PCI, as RC impairs the tubular stress response and intrinsic self-repair mechanisms, exacerbating contrast-induced damage29.

Numerous studies have shown that FPG, LVEF, and BUN are independent factors for CI-AKI30,31,32. This research, using a combination of the Boruta algorithm and logistic regression analysis, identified these same factors as independent predictors of CI-AKI in STEMI patients following PCI. This study developed a traditional model that included FPG, LVEF, and BUN. The ROC analysis indicated that this traditional model achieved an AUC of 0.739 for CI-AKI. After integrating RC, the AUC significantly increased to 0.803, enhancing the model’s ability to identify CI-AKI. Further analysis using IDI and NRI confirmed that incorporating RC significantly improved the CI-AKI risk prediction model. As an easily accessible and calculable clinical biomarker, RC facilitates improved risk stratification for CI-AKI, enabling the timely identification of high-risk STEMI patients for targeted preventive measures.

Study strengths and limitations

This retrospective study possesses several methodological strengths. First, it explores the nonlinear associations between RC and CI-AKI in the STEMI-PCI population, utilizing RCS analyses with multiple knot configurations. Second, the integration of machine learning–driven feature selection, specifically using the Boruta algorithm, with conventional logistic regression helps to enhance the objectivity of variable selection. This approach may offer a modest methodological improvement compared to previous predictive models. Third, incorporating RC significantly improves risk stratification, as evidenced by IDI = 0.053 and NRI = 0.618, thereby highlighting its immediate clinical applicability. This is particularly noteworthy, in light of RC’s cost-effectiveness and its derivability from routine lipid panels.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the single-center, single-ethnicity cohort may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Second, despite adjusting for established confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured variables, such as dietary patterns, may still persist. Third, mechanistic insights into RC’s potential nephrotoxic effects remain speculative until experimental validation is obtained. Finally, external validation across diverse healthcare settings is necessary before clinical implementation.

Conclusion

RC is an independent predictor of CI-AKI in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI. Incorporating RC significantly enhances the predictive model for CI-AKI.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the laboratory’s confidentiality rules, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rear, R., Bell, R. M. & Hausenloy, D. J. Contrast-induced nephropathy following angiography and cardiac interventions. Heart 102(8), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306962 (2016).

Macdonald, D. B. et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists Guidance on Contrast Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 73(3), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/08465371221083970 (2022).

Wilhelm-Leen, E., Montez-Rath, M. E. & Chertow, G. Estimating the risk of radiocontrast-associated nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28(2), 653–659. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016010021 (2017).

Nakano, M. Is longer an obstacle to angiography and intervention in patients with chronic kidney disease?. Circ. J. 86(5), 797–798. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-22-0141 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. The predictive value of SII combined with UHR for contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 7005–7016. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S482977 (2024).

Zhang, F., Lu, Z. & Wang, F. Advances in the pathogenesis and prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy. Life Sci. 259, 118379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118379 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. D-4F ameliorates contrast media-induced oxidative injuries in endothelial cells via the AMPK/PKC pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 556074. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.556074 (2021).

Nordestgaard, B. G. et al. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 298(3), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.3.299 (2007).

Varbo, A. et al. Elevated remnant cholesterol causes both low-grade inflammation and ischemic heart disease, whereas elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol causes ischemic heart disease without inflammation. Circulation 128(12), 1298–1309. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003008 (2013).

Saeed, A. et al. Remnant-like particle cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein triglycerides, and incident cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72(2), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.050 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Correlation between remnant cholesterol and hyperuricemia in American adults. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02167-0 (2024).

Qin, Y. et al. A high triglyceride-glucose index is associated with contrast-induced acute kidney injury in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 522883. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.522883 (2021).

Park, H. S. et al. HDL cholesterol level is associated with contrast induced acute kidney injury in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing PCI. Sci. Rep. 6, 35774. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35774 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. Malnutrition and the risk for contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with coronary artery disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 54(2), 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02915-6 (2022).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455 (2020).

van der Molen, A. J. et al. Post-contrast acute kidney injury—Part 1: Definition, clinical features, incidence, role of contrast medium and risk factors : Recommendations for updated ESUR Contrast Medium Safety Committee guidelines. Eur. Radiol. 28(7), 2845–2855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-5246-5 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. The role of remnant cholesterol in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 31(10), 1227–1237. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae102 (2024).

Quispe, R. et al. Remnant cholesterol predicts cardiovascular disease beyond LDL and ApoB: A primary prevention study. Eur. Heart J. 42(42), 4324–4332. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab432 (2021).

Castañer, O. et al. Remnant cholesterol, not LDL cholesterol, is associated with incident cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76(23), 2712–2724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.008 (2020).

Fu, L. et al. Remnant cholesterol and its visit-to-visit variability predict cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: Findings from the ACCORD cohort. Diabetes Care 45(9), 2136–2143. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-2511 (2022).

Moorhead, J. F. et al. Lipid nephrotoxicity in chronic progressive glomerular and tubulo-interstitial disease. Lancet 2(8311), 1309–1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91513-6 (1982).

Ohmura, H. Contribution of remnant cholesterol to coronary atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 29(12), 1706–1708. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.ED205 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Mechanisms of inflammatory microenvironment formation in cardiometabolic diseases: Molecular and cellular perspectives. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1529903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1529903 (2025).

Xu, J. et al. Change in postprandial level of remnant cholesterol after a daily breakfast in Chinese patients with hypertension. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 685385. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.685385 (2021).

Alloza, I. et al. BIRC6 is associated with vulnerability of carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(24), 9387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249387 (2020).

Bruno, M. E. C. et al. PAI-1 as a critical factor in the resolution of sepsis and acute kidney injury in old age. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 1330433. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1330433 (2024).

Hao, Q. Y. et al. Remnant cholesterol and the risk of coronary artery calcium progression: Insights from the CARDIA and MESA study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 15(7), e014116. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.122.014116 (2022).

Luo, Z. et al. Soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 associated with contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with STEMI. Int. Urol. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-024-04204-4 (2024).

Ma, Q. W. et al. Predictive effect of remnant cholesterol on early diabetic kidney disease. Chin. J. Diabetes 14(11), 1264–1271. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn1115791-20220326-00130 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Association of left ventricular ejection fraction with contrast-induced nephropathy and mortality following coronary angiography or intervention in patients with heart failure. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 13, 887–895. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S137654 (2017).

Shen, G. et al. Predictive value of systemic immune-inflammation index combined with N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide for contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with STEMI after primary PCI. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56(3), 1147–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03762-3 (2024).

Lin, H. H. et al. DDAH-2 alleviates contrast medium iopromide-induced acute kidney injury through nitric oxide synthase. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 133(23), 2361–2378. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20190455 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingkun Jin, Luhong Xu, and Jiahui Ding wrote the main manuscript text. Haiyan He prepared figures and tables. Xishen Zhang, Linsheng Wang, Xudong Zhang, Di Zheng, Jing Zong, Fangfang Li, and Wenhua Li collected the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (approval number: XYFY2022-KL122-01). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, J., Xu, L., Ding, J. et al. Remnant cholesterol associated with contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction following percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep 15, 43334 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27330-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27330-0