Abstract

The agricultural sector confronts escalating challenges, including population growth, climate change, and constrained land resources. Addressing these issues requires agricultural methods to evolve into more intelligent, sustainable, and efficient practices in order to satisfy the expanding global demand. In this context, the smart greenhouse plays a crucial role in contemporary smart agriculture by amalgamating diverse technologies and equipment to establish an optimal environment for plant cultivation. This paper aims to create an enhanced algorithm for ventilation control utilizing artificial intelligence technology. The goal is to achieve intelligent ventilation and air exchange in greenhouses while ensuring that optimal air conditions for crop growth are maintained consistently. Employing data from the Shouguang Vegetable High-Tech Demonstration Park, we collect and analyze historical and real-time data within a glass greenhouse. We establish the foundational algorithm for autonomous ventilation control using an adaptive genetic algorithm-back propagation neural network. A hybrid fitness scaling approach, combining linear and nonlinear fitness scaling, is proposed and implemented. In the pursuit of a well-fitted model, three models i.e., multiple regression (MR), back propagation neural network (BPNN), and genetic algorithm - back propagation neural network (GA-BPNN) are explored in experiments to fit greenhouse data. These models have been validated through extensive simulation experiments, and the results revealed that our method outperforms the investigated techniques in terms of errors. This paper concludes that effective ventilation control algorithms enable precise regulation of greenhouse environmental factors, including temperature, humidity, and CO2, thereby optimizing crop yield and quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

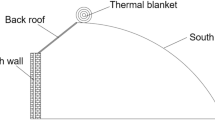

Ventilating a vegetable greenhouse is a crucial technical consideration with a direct impact on the growing conditions and production efficiency of greenhouse vegetables. To ensure the sustained maintenance of optimal temperature conditions for crop growth over the long term, greenhouses, whether traditional solar structures or relatively costly glass ones (refer to Figure 1), typically adopt a relatively airtight design. When the greenhouse is fully enclosed, the gas composition in the indoor air undergoes significant changes over time. This includes an increase in water vapor (mainly from soil evaporation and plant transpiration), a rise in harmful gases (primarily from fertilizer decomposition, etc.), and a decrease in carbon dioxide (CO2) (essential for crop photosynthesis). Implementing ventilation and air exchange system enhances the exchange of indoor and outdoor air, creating a more favorable environment for crop growth and consequently increasing production efficiency.

The growth of plants usually has strict requirements for temperature, light, water, fertilizer, and gas, following the “barrel effect”, and the most problematic component is frequently related to gas. This is especially notable during the winter, when greenhouses are frequently enclosed. Despite significant differences between the interior and exterior environments, the heightened internal temperature and enhanced sealing often result in indoor air humidity reaching saturation. Excess moisture accumulates as a water film on plant leaves, detrimentally affecting crop photosynthesis and respiration, and creating conditions conducive to bacterial growth and the onset of pests and diseases.

(The ideal atmospheric humidity for crop growth is around 65-75% during the daytime and 80-90% at nighttime1.) Additionally, temperature stands out as the foremost determinant of greenhouse vegetable growth and development. Different vegetables exhibit varied optimum growth temperatures during different stages, and extremes, whether too high or too low, can significantly impact plant growth. We present the growth habits of some common greenhouse vegetables and the temperature range conducive to their development in Table 1.

Table 1 displays the germination and growth temperature requirements for various common vegetables, including chili peppers, tomatoes, celery, eggplant, and cucumbers. The concentration of CO2 is directly correlated with crop photosynthesis. In closed greenhouse environments, low CO2 levels can result in sluggish photosynthesis, decreased crop resilience to pests and diseases, compromised quality, and diminished yields2. Beyond CO2, harmful gases such as ammonia (NH3) also pose threats to crops. As indicated by3, cucumbers can perish within 1-2 hours when NH3 concentrations exceed 0.1%-0.8%. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are essential for vegetable growth, however, the breakdown of both organic and artificial fertilizers can release toxic gases such as methane and ammonia. Additionally, the degradation of organic materials within the soil, like fallen leaves, also contributes to the release of toxic gases. Consequently, the presence of these harmful gases in a greenhouse is indubitable.

To consistently enhance crop yields, greenhouse ventilation plays an important role and can be achieved through two methods: 1) natural ventilation (passive ventilation4), relying on the temperature differential between the warmer air inside the greenhouse and the cooler air outside the greenhouse, and 2) forced ventilation (active ventilation), involving the use of mechanical systems to enhance air circulation and facilitate air exchange between the greenhouse and the external environment. 5reviewed the impact of shape and orientation on the availability of solar radiation in greenhouses in various regions with reference to the equator. Wind direction, greenhouse dimensions, vent configurations6, and humidity around the greenhouse are important influencing parameters on the effectiveness of ventilation systems. They also propose a development path of using sensors to build intelligent and automatic feedback. The greenhouse environment, influenced by factors like weather and human activity, exhibits high nonlinearity and strong coupling7. Neural networks, known for their adaptability to both linear and nonlinear contexts, were utilized by7 in the development of an Output Feedback Neural Network (OFNN)-based ventilation control approach, demonstrating high accuracy in managing various aspects. In a study by8, a recurrent dynamic network (NARMX) predictive control approach was employed to optimize water and energy utilization in naturally ventilated and fog-cooled greenhouses, resulting in a near-optimal and uniform crop growth environment.

In hot climate regions of the tropics and subtropics, where air cooling is essential to counteract overheating during summer,9 and10 comprehensively reviewed current greenhouse design and cooling technologies, providing comparisons and critical discussions of multiple cooling systems. 11reviewed greenhouse design and cooling systems in tropics and subtropics, pointing out the interrelationships between greenhouse architecture and cooling mechanisms to achieve anti-climatic sustainable farming. It also pointed to topics for further research, arguing for the selection of appropriate solutions based on local climate and growing conditions.

Globally, scholars have increasingly utilized advanced technologies to augment the efficiency and efficacy of greenhouse agricultural practices. This study employs adaptive GA-BPNN12,13,14 to regulate microclimatic conditions within greenhouses, including temperature, humidity, and CO2, thereby fostering an optimal environment for crop growth. We enhance experimental outcomes through \(\alpha\)-weighted linear and nonlinear mixed fitness scaling. Recognizing the versatility of the Weibull distribution in fitting diverse datasets, we suggest its use as an alternative to the conventional segmented function for determining critical parameters, such as cross probability and mutation probability.

We structure the remainder of the paper as follows: In Section Experimental setup, we provide a detailed account of the data acquisition process for this study, along with an assessment of data validity using quadratic regression. Section Algorithms outlines the methodology’s structure, delving into the enhanced fitness scaling function and analyzing the fitting effects of the Weibull, One-phase exponential decay (ExpDec1)15,16, and Boltzmann functions17,18. Discussion of the experimental results takes place in Section 4, where various algorithms such as BPNN19,20, GA-BPNN, etc., are analyzed in terms of their adherence to the original data. Finally, Section Conclusion and future work offers concluding remarks on the overall study.

Experimental setup

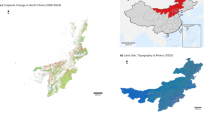

The study’s experimental site was selected in ShouGuang, a prominent vegetable base in China. ShouGuang’s diverse range and widespread distribution of vegetable greenhouses offer ample experimental data for our research purposes. (Refer to Figure 2).

Data collected from an authentic glass greenhouse includes wind speed (m/s), levels of toxic gases (%), CO2 (%), temperature (\(^{\circ }\text {C}\)), and humidity (%). The wind speed represents the airflow rate within the greenhouse, facilitated by fans and ventilation windows according to greenhouse environmental conditions. We assessed the data’s credibility by constructing a quadratic regression model to correlate wind speed, ensuring alignment between the model’s outcomes and real-world observations.

We utilize quadratic regression to map the wind speed and other variables because it better reflects the monotonic relationship between the data while avoiding the drawbacks of unnecessarily complicated high-order polynomial fits. The model considers wind speed to be the independent variable and other factors to be the dependent variables, and the interval of the independent variable is too small to fit the model. However, to reflect the trend of other factors with wind speed, the small interval of the independent variable has little effect on this model. The results of the regression analysis are shown in Figure 3.

In Figure 3(A), the scatter plot illustrates the relationship between wind speed and toxic gases alongside the quadratic fitting curve. It reveals a gradual decrease in toxic gases as wind speed increases, indicating that higher wind speeds correspond to lower concentrations of toxic gases during greenhouse ventilation. Further scrutiny of the regression curve demonstrates that the rate of decrease in toxic gases accelerates with rising wind speed, forming a convex function that aligns well with real-world observations, thus validating the regression outcome.

Figure 3(B) displays the scatter plot of wind speed against CO2 concentration, along with the quadratic regression curve. Despite data points being scattered, the initial portion of the regression curve indicates a consistent increase in CO2 levels with escalating wind speeds, albeit with a gradual slowdown in the rate of increase. The CO2 increase nearly plateaus around the interval \(\left[ 1.8, 1.9\right]\), closely mirroring the typical atmospheric CO2 concentration of 0.03%. However, due to irregular sampling intervals, the latter part of the curve shows a decline in CO2 with wind speed, deviating from the expected scenario. Nevertheless, the overall regression curve provides insights into the relationship between wind speed and CO2.

Figures 3(C) and 3(D) demonstrate the correlation between wind speed and temperature, and wind speed and humidity, respectively. Both temperature and humidity exhibit a consistent decrease with increasing wind speed, with the rate of decline gradually tapering off. This is attributed to wind enhancing evaporation and transpiration from plants and soil, thereby reducing atmospheric moisture content. Consequently, higher wind speeds lead to increased moisture transport and lower humidity levels.

Algorithms

Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)

UMAP21 is a dimensionality reduction approach that aims to preserve the underlying structure of high-dimensional data. It uses concepts from topology and graph theory to construct a weighted K-nearest neighbor graph, denoted as G, based on the original data.

Let \(X={x_{1}, x_{2},..., x_{n}}\) represent the high-dimensional dataset, with each \(x_{i}\in \mathbb {R}^{d}\) representing a data point. UMAP generates G by employing a distance metric such as Euclidean distance to connect each data point to its k nearest neighbors. The graph G depicts the proximity relationships between the data points.

To generate a lower-dimensional representation, UMAP learns a smooth and uniform manifold that approximates the original high-dimensional space. Let \(Y={y_{1}, y_{2},..., y_{n}}\) represent X’s low-dimensional embedding, where each \(y_{i} \in \mathbb {R}^{k}\) represents a reduced-dimensional point. UMAP seeks Y such that it retains both the data’s local and global structures.

UMAP optimizes a cost function composed of two terms: localization and cross-entropy. The localization term encourages neighboring points in high-dimensional space to stay close in low-dimensional space. It can be expressed as:

Here, \(D_{l}(\cdot , \cdot )\) denotes the low-dimensional distance metric, \(D_{h}\) means the high-dimensional distance metric, \(W_{ij}\) is the weight of the edge between \(x_{i}\) and \(x_{j}\) in the graph G, and \(Q_{ij}\) stands for the pairwise similarity of \(x_{i}\) and \(x_{j}\).

where \(P_{ij}, Q_{ij}\) denote the similarity between neighboring points in high-dimensional space and low-dimensional space, respectively. The other parameters have the same meaning as Eq. 1.

Analysis of the effect of UMAP on model performance: By mapping high-dimensional data to low-dimensional space, UMAP reduces the number of model parameters, which decreases model complexity and enhances its generalization. UMAP identifies and removes highly correlated features from greenhouse environment data, improving the quality of features and enabling the model to capture the complex dynamic changes in greenhouses more effectively. UMAP also shortens training time, increasing model efficiency. However, dimensionality reduction makes the data lose its clear physical meaning, reducing its interpretability.

Genetic algorithm

Genetic Algorithms(GAs)22,23,24,25 are a parallel stochastic search optimization algorithm that mimics the process of biological evolution via genetic variations and converts issue solutions into “population” search problems directed by randomized techniques. GAs utilize mutation and selection to find optimal solutions to complex problems. Selection weeds out worse-performing alternatives to allow only the best to survive and reproduce, whereas mutation generates diverse candidate solutions to prevent being stuck in local optima. This combination ensures consistent progress towards superior solutions. If the search space allows for it, a near-optimal solution may emerge over many generations.

The individual decision variables (IDVs) \(X=X_{1}X_{2}\cdots X_{n}\) corresponding to the n-dimensional decision vector \(X=[x_{1},x_{2},\cdots ,x_{n}]^{T}\) are the unknown quantities to be solved, and all IDVs constitute the solution space of the problem. The search for the optimal solution of the problem is performed by genetic and evolutionary operations on the population composed of M-IDVs, and the IDVs are made to approach the optimal solution \(X^{*}\) after several iterations.

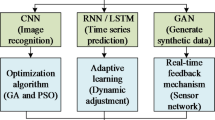

From finding the shortest path in a graph to designing novel pharmaceuticals or materials, GAs can tackle a wide range of optimization challenges. They have been employed in a variety of industries, such as engineering, finance, and artificial intelligence. Figure 4 shows the genetic algorithm flow.

Structure design of GA-BP neural network

To create a GA-BP neural network (GA-BPNN) model, first construct the neural network topology and decide the number of input, output, and hidden layers. The genetic algorithm generates an initial population of chromosomes by coding, taking the training and test sets as input, and cycling to solve the optimal error in order to determine the optimal weights and offsets, which are then substituted into the BPNN for computation.

Figure 5 shows the GA-BPNN architecture used in this paper, where \(x_{i}\left( i=1,2,...,n\right)\) denotes the input node, \(y_{i}\left( i=1,2,...,k\right)\) represents the output node, \(h_{i}\left( i=1,2,...,m\right)\) is the hidden node. \(W_{i},B_{i}\left( i=1,2 \right)\) are the weight and bias, respectively.

The procedures of the algorithm are as follows:

Step 1: During the training phase, the algorithm takes critical environmental parameters (wind speed (m/s), levels of toxic gases (%), CO2 (%), temperature (\(^{\circ }\text {C}\)), and humidity (%)) as input parameters, which are then passed to Step 3 as training data after UMAP dimensionality reduction and data verification.

Step 2: Input nodes (\(x_{i}\)), hidden nodes (\(h_{i}\)), and output nodes (\(y_{i}\)) of the exploited neural network (net) are constructed. The GA randomly creates an initial chromosomal population, which serves as the neural network weights (\(W_{1}, W_{2}\)) and biases (\(B_{1}, B_{2}\)), and calculates the first fitness.

Step 3: The GA codes the training data into a new population of chromosomes, which are selected during the GA evolution. During iterations, the best-performing individual is evaluated from the population through cross, mutation, and selection operators based on fitness scores, yielding the optimal initial weights and biases. The neural network can utilize the optimal value directly to accelerate convergence and improve efficiency during training.

Step 4: In the control phase, the program collects environmental parameters in real-time and continuously, which are fed into the net to calculate the optimal wind speed (i.e., output) and provide control signals for devices such as fans and vents accordingly.

The algorithm, driven by data, can adapt to dynamic changes in the environment to some extent. Any complex nonlinear relationship can be captured by data approximation of DNN, which can also rapidly converge and approach optimality with the assistance of GA for optimization. Therefore, the model has high generality and extensive applicability potential, and is not limited to specific greenhouses.

Fitness scaling

In genetic algorithms, fitness value is a numerical score awarded to each individual in a population. It compares the proximity of each candidate solution to optimality depending on the fitness functions defined beforehand. As the algorithm converges, the fitness values of all IDVs in the population become very close to each other, making optimization difficult and causing the GAs to oscillate too much at the optimal solution. To improve the GAs, we employed fitness scaling, which includes linear and nonlinear fitness scaling, using the following equations, respectively:

Linear fitness scaling: \(f^{*}=h_{1}f+h_{2}\), where f and \(f^{*}\) are the values of the fitness function before and after fitness scaling, respectively. \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\) denote the two newly added hyperparameters. \(h_{1}, h_{2}\) take different values and consequently have varied expressions for various scenarios, typically:

Minimum Scaling Transform:

Maximum Scaling Transform:

where \(f_{min}, f_{max}\) are the minimum and maximum of the fitness function before scaling transform, and \(\Delta \in \left( 0,1\right)\) is to improve the randomness of the population.

Nonlinear fitness scaling: The more typical methods are power-law fitness scaling and logarithmic fitness scaling, which have the following expressions:

Power-law fitness scaling:

where \(k>1\) indicates the selective pressure increased, while \(k<1\) denotes the selective pressure decreased.

Logarithmic fitness scaling:

where \(h_{1}, h_{2}\) are new hyperparameters.

Weibull-based adaptive genetic algorithm

We adjust the aforementioned fitness scaling formula (see section 2.4) as follows, based on the application scenario and data characteristics of this work:

where \(\Phi\), \({\Phi }^{*}\) indicate the pre-scaling and post-scaling values, respectively. \(\eta \in (0,1)\) is to prevent the denominator from being zero, while allowing the worst individual in the population to be selected, hence enhancing the randomness of group selection.

In Figure 6, we find that a single method cannot achieve good scaling transform results for this study. As we can see in Figure 6(A), the curve of fitness converges slowly, i.e., epoch=20, and eventually to around 10, which is larger than expected. Figure 6(B) shows the curve with the linear fitness scaling, which converges around 12th epoch, somewhat quicker than Figure 6(A), and the fitness value ends up about 11, which is still on the large side. The power-law fitness scaling (k=2) is slightly better than the first two, faster (epoch<10) in terms of convergence speed, and with a smaller value (around 5), as we see in Figure 6(C). The natural logarithm fitness scaling is used in Figure 6(D), and the fitness eventually stabilizes between 6 and 7 and converges slowly compared to the power-law fitness scaling. We conclude that the algorithm converges faster and the process is more stable after applying power-law fitness scaling compared to linear and natural logarithm fitness scaling, thus implying that power-law fitness scaling is more suitable in this scenario.

We employ a hybrid fitness scaling method based on linear and non-linear fitness scaling to further improve experimental results, with the following formula:

where \(\alpha \in [0,1]\) is a newly introduced trade-off factor for weighing the linear and nonlinear components. Among the above formulas, Eq. 10 shows the hybrid scaling method with natural logarithmic scaling and linear scaling, which will be mainly applied in our algorithm. In order to ensure the study’s completeness, we also provide the power-law version (as in Eq. 11) to interested scholars.

Cross probability \(p_{c}\) and mutation probability \(p_{m}\) in GAs are critical for determining the behavior and performance of GAs, and directly affect the convergence of the algorithms. The larger \(p_{c}\), \(p_{m}\), the faster new individuals are created, however, when \(p_{c}\), \(p_{m}\) are too large, the risk of genetic patterns being disrupted increases, and the structure of individuals with high fitness is quickly destroyed. Too small, the \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) slow the search process and even halt it. Many scholars26,27,28,29,30 studied adaptive genetic algorithms and proposed a variety of strategies for dynamic adjustment of relevant parameters, such as \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\), which are dynamically adjusted with reference to individual fitness. The most representative method is employed in27, and the calculations of \(p_{c}\), \(p_{m}\) are shown as Eqs. 12 and 13 :

where \(f_{avg}, f_{max}, f_{min}\) denote the average, maximum, and minimum values of population fitness. Here, we set \(k_{1}, k_{2}, k_{3}, k_{4}\) to 0.7, 0.55, 0.1, 0.001, respectively. These strategies, however, don’t employ continuous functions, when individual fitness values exceed the average, \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) jump, causing greater fluctuations in the average fitness, indicating the need for a more stable and continuous weighting function.

Basically, \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) are reduced when population fitness is relatively dispersed, and \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) are increased accordingly when population fitness tends to be consistent. At the same time, if an individual’s fitness is lower than the average fitness, it indicates that the individual is not performing well and a higher probability can be used for it, whereas if the fitness is higher than the average fitness, it indicates that the individual is performing well and a lower probability can be used for it. As fitness approaches maximum fitness, \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) tend to zero.

Based on the above considerations and the observation of the existing probability dynamics adjustment, we generate \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) with the Weibull distribution31,32. The Weibull distribution is a continuous probability distribution that reflects the probability of an event occurring over a particular time or distance period. It is frequently used to simulate the survival periods or lifespans of mechanical components or other physical phenomena that are prone to wear or failure as a result of random occurrences. The probability density function (PDF) is:

where \(\alpha\) denotes the scale parameter of the Weibull distribution, \(\gamma\) is the shape parameter of it, and u represents the location at which the distribution begins. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) is defined as:

The mean and variance are given as follows:

where \(\Gamma \left( \cdot \right)\) is the Gamma function, i.e., \(\Gamma \left( n\right) =\int _{0}^{\infty }t^{n-1}e^{-t}dt, n>0\).

Figure 7 shows the fit of the Weibull, ExpDec1, and Boltzmann functions versus \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) data, which were generated according to traditional adaptive genetic algorithms27. The Weibull PDF function is employed here with a modification on Eq.( 14):

where \(y_{0}\) and \(p_{0}\) are the offsets on the y and x axes, respectively. The function of ExpDec115,16 is:

where \(y_{0}\) denotes the offset on the y-axis, \(A_{1}\) is the amplitude, and \(t_{1}\) stands for the time constant. The Boltzmann function17,18 is:

where \(A_{1}\) and \(A_{2}\) are the bottom and top values, respectively. \(p_{0}\) means the center (i.e., 50% threshold at \((p_{0},(A_{1}+A_{2})/2)\)) value), and dp is the time constant.

As can be seen in Figures 7(A) and 7(B), the curves of the Weibull PDF closely correspond to the histograms of the real data of \(p_{c}\) and \(p_{m}\) for all the methods analyzed. Figure 7(C) shows that the convergence is faster relative to the single fitness scaling method, and the convergence value of the fitness is around 0, which is small, confirming our hypothesis. The value of the trade-off factor, \(\alpha =0.475\) chosen, may fluctuate depending on the hardware/software environment and must be fine-tuned accordingly.

Results and discussions

Maintaining stringent controls for consistency, all experimental procedures were within a uniform hardware environment that aligns with the setting identical to earlier experiments, inclusive of a specified learning rate of 0.001. To enable a lucid comparison of prediction outcomes, our algorithms were positioned against an ensemble of models, including BPNN, GA-BPNN, Linear SGA-BPNN (Linear fitness scaling GA-BPNN), PLSGA-BPNN (Power-law fitness scaling GA-BPNN), log SGA-BPNN (Logarithm fitness scaling GA-BPNN), and the original data. We integrated an examination of the residuals from each respective methodology to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced evaluation of their comparative performance.

The results are as follows:

Comparison of simulation results of multiple algorithms. (A) BP neural network and our method. (B) Vinilla GA-BP neural network and our method. (C) GA-BP neural network with linear fitness scaling (Linear SGA-BP) and our method. (D) GA-BP neural network with power-law fitness scaling (PLSGA-BP) and our method. (E) GA-BP neural network with logarithm fitness scaling (Log SGA-BP) and our method. (F) Error plots for all algorithms.

In Figures 8(A)- 8(E), it can be seen that our method is closer to the original signal. Figure 8(F) shows the residual curves of various algorithms appearing in this research, from which it can be seen that the fluctuation of our method is relatively small and generally near “0”. In order to compare the effectiveness of the algorithms more explicitly, we calculated the mean absolute error (\(MAE=\frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\left| x_{i}-\widehat{x_{i}}\right|\)) and the mean squared error(\(MSE=\frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\left( x_{i}-\widehat{x_{i}} \right) ^{2}\)) for each algorithm, and computed the P-value through the T-test, as shown in Table 2.

In Table 2, we find that MAE and MSE for multiple regression (MR) are 1.7702 and 3.2143, respectively, with maximum values, which means the worst performance of MR compared to other algorithms. Our algorithm with the minimum values of MAE and MSE, i.e., 0.0533 and 0.0091, respectively, suggests that the results are closest to the original data. The p-values can also roughly indicate this pattern. Based on the characteristics of the data, we compare whether there is a significant difference between the mean values of two vectors using the T-test. If the p-value is small (typically less than 0.05), it indicates a significant difference between the two vectors. We found that the p-value for MR is 0.0984, which is close to 0.05, indicating the worst fit. Our method has the highest p-value of 0.8831, indicating the best fit. Based on the available data, a system-wise search was performed, and our model could obtain optimum ventilation conditions: toxic gases (%) 0.0700, CO2 (%) 0.0050, temperature (\(^{\circ }\text {C}\)) 30, humidity (%) 85.5, and the estimated ideal wind speed was 1.6423.

From Table 2, it can be seen that MR performs the worst, as the manually designed higher-order terms cannot adapt to the dynamic changes in the data, and its accuracy relies more on the designer’s experience, leading to significant errors. The parameter optimization of BP-NN takes more time and is prone to getting stuck in local optima, affecting its precision. Linear SGA-BPNN, PLSGA-BPNN, and Log SGA-BPNN are suitable for linear, exponential, and logarithmic data, respectively, while data in nature typically do not follow a specific pattern. Our method employs hybrid fitness scaling that fuses linear and nonlinear features and uses the Weibull distribution for faster convergence.

Conclusion and future work

Conclusion

Nowadays, the utilization of artificial intelligence (AI) within the realm of smart agriculture stands as a prominent research area, bearing significant implications for the advancement of smart agriculture practices. This paper combines the current state of Shouguang smart agriculture with an in-depth study of the fundamental algorithm. The experimental results show that MR requires manual design of higher-order terms when modeling nonlinear relationships, whereas GA-BPNN automatically captures complex coupling relationships through hidden layers. Compared to MR, GA-BPNN, through its global search strategy, is more likely to escape local optima and find better network parameters. Inheriting the advantages of GA and neural networks, GA-BPNN exhibits stronger generalization capabilities and is well-suited for various regression tasks. Although it is slightly more complex than MR, its prediction results are more accurate.

The main contribution of the study: First, we rely on the Shouguang High-Tech Vegetable Expo to analyze environmental data on greenhouse vegetable productions and conduct in-depth research on the fundamental algorithms. Second, we apply UMAP to downsize the training data and analyze its validity with multiple regression. And then, to address the issue of low accuracy of the GA-BP neural network, we offer the hybrid fitness scaling and Weibull distribution improvement method, which achieves better results. Outstanding experimental results verify the superiority of the proposed ventilation algorithm.

The potential limitations: To improve space utilization and production efficiency, a variety of crops are usually grown in greenhouses. Different crops have different requirements for ventilation, and the same crop has different requirements for ventilation at different growth stages, which brings great challenges to our research. In addition, the model training requires a large amount of data.

Future work

From an efficiency point of view, traditional agriculture tends to rely on experience, which makes it difficult to control the greenhouse environment precisely. This management method not only leads to energy waste but also affects the growth rate and quality of crops. Automated ventilation, through intelligent algorithms, achieves precise environmental control, optimizing resource utilization and freeing growers from tedious manual operations. With less input, more output is obtained, thereby significantly improving the efficiency of agricultural production. From the perspective of sustainability, our approach aims to build an environment-friendly, green agricultural production model. It enables precise control of environmental factors based on crop needs, reducing unnecessary resource waste.

This study not only helps protect the ecological environment but also lays the foundation for future agricultural development. The future direction of this work is to apply the proposed algorithm to the glass greenhouse ventilation system to test its effectiveness in the real-world application environment, and to improve the accuracy under the premise of minimizing the training data.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goldammer, T. Greenhouse management: a guide to operations and technology (Apex publishers, 2019).

Thompson, M., Gamage, D., Hirotsu, N., Martin, A. & Seneweera, S. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide on photosynthesis and carbon partitioning: A perspective on root sugar sensing and hormonal crosstalk. Front. Physiol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00578 (2017).

Wdowikowska, A. et al. Water and nutrient recovery for cucumber hydroponic cultivation in simultaneous biological treatment of urine and grey water. Plants 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12061286 (2023).

Boulard, T., Haxaire, R., Lamrani, M., Roy, J. & Jaffrin, A. Characterization and modelling of the air fluxes induced by natural ventilation in a greenhouse. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 74, 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1006/jaer.1999.0442 (1999).

Akrami, M. et al. Towards a sustainable greenhouse: Review of trends and emerging practices in analysing greenhouse ventilation requirements to sustain maximum agricultural yield. Sustainability 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072794 (2020).

Akrami, M. et al. Study of the effects of vent configuration on mono-span greenhouse ventilation using computational fluid dynamics. Sustainability 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030986 (2020).

Jung, D.-H., Kim, H.-J., Kim, J. Y., Lee, T. S. & Park, S. H. Model predictive control via output feedback neural network for improved multi-window greenhouse ventilation control. Sensors 20, 1756 (2020).

Fitz-Rodríguez, E. et al. Neural network predictive control in a naturally ventilated and fog cooled greenhouse. In International Symposium on Advanced Technologies and Management Towards Sustainable Greenhouse Ecosystems: Greensys 2011(952), 45–52 (2011).

Ghoulem, M., El Moueddeb, K., Nehdi, E., Boukhanouf, R. & Kaiser Calautit, J. Greenhouse design and cooling technologies for sustainable food cultivation in hot climates: Review of current practice and future status. Biosyst. Eng. 183, 121–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.04.016 (2019).

Kumar, K., Tiwari, K. & Jha, M. K. Design and technology for greenhouse cooling in tropical and subtropical regions: A review. Energy and Buildings 41, 1269–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2009.08.003 (2009).

Sethi, V. On the selection of shape and orientation of a greenhouse: Thermal modeling and experimental validation. Sol.Energy 83, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2008.05.018 (2009).

Ou, Y., Ye, S.-Q., Ding, L., Zhou, K.-Q. & Zain, A. M. Hybrid knowledge extraction framework using modified adaptive genetic algorithm and bpnn. IEEE Access 10, 72037–72050 (2022).

Zhang, J. & Qu, S. Optimization of backpropagation neural network under the adaptive genetic algorithm. Complexity 2021, 1–9 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Application of ga-bpnn on estimating the flow rate of a centrifugal pump. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105738 (2023).

Suresh, S., Shettar, M., Gowrishankar, M. & Sharma, S. Durability analysis on properties of water soaked pnncs and cs-ann model for wear property analysis of pnncs. Cogent Eng. 10, 2213977 (2023).

Zeng, F. et al. Improvement in the intense pulsed emission stability of grown cnt films via an electroless plated ni layer. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 2379–2382 (2011).

Sevcik, C. Caveat on the boltzmann distribution function use in biology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 127, 33–42 (2017).

Decelle, A., Seoane, B. & Rosset, L. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering using the learning dynamics of restricted boltzmann machines. Phys. Rev. E 108, 014110 (2023).

Zheng, S. et al. An accurate forest fire recognition method based on improved bpnn and iot. Remote. Sens. 15, 2365 (2023).

Ben, S. J., Dörner, M., Günther, M. P., von Känel, R. & Euler, S. Proof of concept: Predicting distress in cancer patients using back propagation neural network (bpnn). Heliyon 9 (2023).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426 (2018).

Katoch, S., Chauhan, S. S. & Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 8091–8126 (2021).

Alhijawi, B. & Awajan, A. Genetic algorithms: Theory, genetic operators, solutions, and applications. Evol. Intell. 1–12 (2023).

Acampora, G., Chiatto, A. & Vitiello, A. Genetic algorithms as classical optimizer for the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 142, 110296 (2023).

Ghezelbash, R., Maghsoudi, A., Shamekhi, M., Pradhan, B. & Daviran, M. Genetic algorithm to optimize the svm and k-means algorithms for mapping of mineral prospectivity. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 719–733 (2023).

Han, S. & Xiao, L. An improved adaptive genetic algorithm. In SHS Web of Conferences, vol. 140, 01044 (EDP Sciences, 2022).

Gao, Y., Ma, C. & Wang, T. Fault diagnosis for cooling dehumidifier based on fuzzy classifier optimized by adaptive genetic algorithm. Heliyon 8 (2022).

Kuptametee, C., Michalopoulou, Z.-H. & Aunsri, N. Adaptive genetic algorithm-based particle herding scheme for mitigating particle impoverishment. Measurement 214, 112785 (2023).

Alshammari, H. et al. Optimal deep learning model for olive disease diagnosis based on an adaptive genetic algorithm. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 1–13 (2022).

Han, Y., Hu, H. & Guo, Y. Energy-aware and trust-based secure routing protocol for wireless sensor networks using adaptive genetic algorithm. IEEE Access 10, 11538–11550 (2022).

Ramos, P. L., Almeida, M. H., Louzada, F., Flores, E. & Moala, F. A. Objective bayesian inference for the capability index of the weibull distribution and its generalization. Comput. & Ind. Eng. 167, 108012 (2022).

Teimourian, H., Abubakar, M., Yildiz, M. & Teimourian, A. A comparative study on wind energy assessment distribution models: A case study on weibull distribution. Energies 15, 5684 (2022).

Funding

This research was supported by Weifang University of Science and Technology High-Level Talent Fund Project under grant (KJRC2025006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW and CZ wrote sections of the manuscript and prepared the figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, ZY., Zhang, CP., Alam, M. et al. Application of adaptive GA-BPNN based on weibull distribution for autonomous greenhouse ventilation. Sci Rep 15, 43245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27333-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27333-x