Abstract

This paper introduces the Gray Wolf Optimized Convolutional Transformer Network, a combined deep learning framework aimed at accurately and efficiently recognizing dynamic hand gestures, especially in American Sign Language (ASL). The model integrates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for spatial feature extraction, Transformers for temporal sequence modeling, and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for hyperparameter tuning. Extensive experiments were conducted on two benchmark datasets, ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST to validate the model’s effectiveness in both static and dynamic sign classification. The proposed model achieved superior performance across all key metrics, including a accuracy of 99.40%, F1-score of 99.31%, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.988, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.992, surpassing existing models such as PCA-IGWO, KPCA-IGWO, GWO-CNN, and AEGWO-NET. Real-time gesture detection outputs further demonstrated the model’s robustness in varied environmental conditions and its applicability in assistive communication technologies. Additionally, the integration of GWO not only accelerated convergence but also enhanced generalization by optimally selecting model configurations. The results show that GWO-CTransNet offers a powerful, scalable solution for vision-based sign language recognition systems, combining high accuracy, fast inference, and adaptability in real-world applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hand gesture recognition (HGR) has emerged as a pivotal modality for human–computer interaction (HCI), offering an intuitive, device-free communication medium across domains such as assistive technologies, virtual environments, robotics, and sign language interpretation1. Among various HGR systems, vision-based dynamic gesture recognition has received growing attention due to its capacity to capture spatiotemporal dependencies in real-time motion sequences2. However, despite advancements in deep learning, several limitations persist, especially in handling gesture ambiguity, motion blur, lighting variability, and background complexity3.

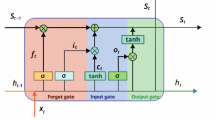

Moreover, traditional models for HGR often rely either on 2D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which effectively extract spatial features but lack temporal modeling capability, or on recurrent networks such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to capture temporal dependencies at the expense of spatial detail4. While 3D CNNs and hybrid networks have been proposed to address this divide5, their computational cost and inability to generalize across varying contexts limit their practical deployment. Also, handcrafted features or manually selected hyperparameters can hinder performance when transferred to unseen environments or user-specific gesture styles6.

To further improve recognition accuracy and adaptability, several works have explored metaheuristic optimization techniques, particularly in feature selection and hyperparameter tuning. Swarm Intelligence Algorithms, such as Particle Swarm Optimization and the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), have shown promise in refining neural network performance by guiding the selection of optimal network configurations or data features7. However, most existing applications of GWO have been limited to feature-level optimization rather than the deeper architectural tuning of hybrid networks trained in an end-to-end approach. Simultaneously, Transformer-based architectures have revolutionized sequential data modeling by using self-attention mechanisms to learn global temporal relationships without the limitations of recurrence8. While such models have recently been adapted for gesture recognition tasks, they remain underexplored in conjunction with CNNs for real-time dynamic hand gesture recognition in American Sign Language (ASL) context9. Additionally, recent studies emphasize the importance of personalized gesture representations and the incorporation of semantic or linguistic context to reflect diverse user behaviors and cultural variations10.

Meanwhile, another key factor influencing the performance of vision-based hand gesture recognition systems is the availability and quality of annotated datasets. High-performing deep learning models typically require large volumes of labeled data to generalize effectively across diverse scenarios11. However, many existing datasets either lack dynamic gesture sequences, are limited in signer diversity, or fail to incorporate real-world environmental variations such as occlusion, lighting inconsistencies, and complex backgrounds. These constraints pose significant barriers to training models that are robust in unconstrained context. In response, researchers have begun to explore synthetic data augmentation, self-supervised pretraining, and multimodal fusion as mechanisms to reduce data dependence and enhance model robustness. In particular, the integration of skeleton-based tracking data, optical flow, and depth information with RGB inputs has shown promise in improving temporal coherence and interpretability. Still, these strategies often increase the complexity of the overall model and impose additional computational costs. Thus, there remains a critical need for models that can efficiently use limited data while maintaining high accuracy and real-time applicability particularly in assistive technologies where low latency and ease of deployment are paramount12.

Moreover, the interplay between spatial and temporal information in dynamic hand gestures has driven research toward more cohesive, end-to-end trainable architectures that can jointly encode both modalities. This has led to the emergence of dual-stream networks and cross-modal attention mechanisms, where one branch captures spatial appearance and the other models motion dynamics. These approaches, while effective, often rely on manual tuning of hyperparameters and are susceptible to overfitting on small or homogenous datasets13. Consequently, attention has shifted toward embedding optimization strategies directly within the learning pipeline. Here, metaheuristic techniques like GWO not only assist in reducing model complexity but also adaptively explore the hyperparameter space to prevent convergence toward local optima. Unlike grid search or random search, GWO mimics the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of wolves, offering a more biologically inspired method of navigating high-dimensional search spaces. Integrating such adaptive learning mechanisms with state-of-the-art neural modules presents a compelling solution for creating more generalizable gesture recognition systems14.

On the other hand, the fusion of semantic information with gesture recognition is becoming increasingly relevant, particularly in tasks that demand contextual understanding, such as sign language interpretation15. Gestures are not only defined by their physical movements but also carry linguistic and cultural subtleties that must be preserved for accurate translation. To this end, recent studies have explored the use of pre-trained word embeddings, semantic segmentation, and context-aware decoders to enhance gesture-to-text systems. These efforts underline the importance of designing architectures that are not merely perceptual but also capable of semantic reasoning.

Therefore, motivated by these observations, this study proposes a novel hybrid architecture named GWO-CTransNet (Gray Wolf Optimized Convolutional Transformer Network), designed to perform dynamic ASL gesture recognition by combining spatial feature extraction via CNNs with temporal modeling through Transformer encoders. In contrast to prior works that utilize GWO for shallow feature selection, our model uniquely uses GWO as a meta-learning mechanism to optimize core hyperparameters across the CNN-Transformer pipeline, including filter sizes, attention head counts, dropout rates, and learning rates. This integration allows for adaptive tuning based on the specific structure of dynamic ASL gesture data.

The main contribution of this paper includes the following:

-

A novel hybrid architecture that integrates CNN-based spatial processing with Transformer-based temporal attention mechanisms for dynamic ASL recognition.

-

The deployment of GWO for end-to-end hyperparameter optimization, offering improved convergence and classification performance over manual tuning methods.

-

Empirical validation using standard ASL datasets as well as custom-recorded samples to demonstrate generalization under diverse environmental conditions.

-

An ablation study and comparative analysis with baseline models, highlighting the performance gains introduced by GWO-based tuning and Transformer integration.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section “Review of related work” reviews the literature related to CNNs, Transformers, and swarm-based optimization in HGR. Section “System model and problem description” details the proposed GWO-CTransNet model and evaluation metrics. Section “Experimental environment and result analysis” presents the experimental setup, datasets, and discusses the results and gesture outcome findings. Finally, Section “Conclusion and future work” concludes the paper and outlines future directions for real-time deployment and full ASL translation.

Review of related work

Sign language recognition (SLR) has experienced a transformative evolution in recent years, primarily motivated by the goal of creating more inclusive technologies that bridge the communication gap between the deaf and the hearing populations. This evolution has been significantly enabled by advancements in deep learning and the application of bio-inspired optimization techniques. The related work in this area is extensive and spans various computational methodologies, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Transformer architectures, and hybrid models integrating optimization strategies such as Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO). This section discusses related work across these domains and highlights key contributions, research gaps, and motivations underpinning the proposed GWO-CTransNet framework.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as a cornerstone in the field of computer vision and have been extensively adopted for tasks involving static and isolated gesture recognition16. Their ability to automatically learn and extract spatial hierarchies and local patterns from image data makes them particularly well-suited for processing the intricate hand shapes and postures that define various sign language gestures. CNNs can recognize features such as edges, corners, and contours, and build upon them in deeper layers to identify more abstract representations of input gestures. This makes them highly effective in environments where gestures are consistent, isolated, and performed under controlled lighting and background conditions. A notable example of CNN-based SLR is the research by author17, who introduced AEGWO-Net, a hybrid model that incorporates traditional Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) features as the initial descriptor. These features are subsequently refined using an unsupervised autoencoder to reduce dimensionality and remove redundancy.

To further enhance performance, the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is used to perform feature selection, resulting in a compact and informative set of features. The AEGWO-Net model demonstrated impressive performance across several benchmark datasets, with high accuracy and F1-scores, showcasing the potential of combining handcrafted descriptors with bio-inspired optimization techniques. However, a significant limitation of such models is their dependency on handcrafted features like HOG, which lack the flexibility and robustness needed in more dynamic or real-world scenarios. Author17 addressed this by developing a lightweight ANN model capable of real-time gesture recognition with low computational overhead. While these improvements aid in practical deployment, standalone ANNs still fall short in capturing temporal dependencies between sequential frames, a critical aspect for recognizing dynamic gestures. This limitation highlights the need for hybrid models that integrate ANNs with temporal architectures like CNNs or Transformers to achieve comprehensive gesture recognition in continuous sign language settings.

Meanwhile, transformers have gained significant prominence in the domain of sign language recognition (SLR), particularly for their capability to model temporal dynamics more effectively than traditional sequence models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. What sets Transformers apart is their use of self-attention mechanisms, which allow them to simultaneously consider all positions in a sequence when computing the representation of each element18. This parallelization not only improves computational efficiency but also enables the model to capture long-range dependencies and complex temporal relationships that are critical in recognizing fluid sign language gestures.

Unlike RNNs, which process data sequentially and often suffer from vanishing gradient issues over long sequences, Transformers can learn global context with ease, making them ideal for tasks where temporal order and cross-frame dependencies are essential. One of the pioneering works in this area is by author19, who proposed an end-to-end continuous sign language recognition framework using spatial channel attention inception-net. Their model demonstrated substantial improvements over RNN-based baselines, especially in tasks involving gloss prediction and temporal alignment of gesture sequences. The use of attention allowed the system to focus selectively on keyframes and gesture components, enhancing recognition accuracy and interpretability. Building on this, author20 introduced the NationalCSL-DP dataset, which incorporates dual-view recordings of signers performing dynamic gestures in Chinese language. This dataset addressed some of the limitations of earlier datasets by introducing greater variability in viewpoint and signer diversity. Their experiments showed that models trained on dual-view data, particularly those based on Transformer architectures, performed better in complex, real-world scenarios. This underscores the value of integrating high-capacity models like Transformers with diverse datasets for building robust, scalable SLR systems capable of functioning in naturalistic environments.

On the other hand, hybrid models that combine the strengths of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for spatial feature extraction with sequential models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Transformers for temporal modeling have garnered substantial attention in the field of sign language recognition21. These architectures are designed to overcome the limitations of standalone CNNs, which excel in identifying static spatial patterns but lack the capacity to interpret temporal sequences inherent in dynamic gestures. By integrating spatial and temporal modules, hybrid models are better equipped to capture the full context of a gesture, particularly when it involves transitions, velocity changes, or coarticulation effects that are common in natural sign language. A compelling example of such an approach is the CNNSa-LSTM model proposed by author21 which enhances spatial feature maps produced by CNN layers using an attention mechanism before feeding them into an LSTM network. This fusion enables the model to focus on salient gesture regions while simultaneously learning their temporal evolution. Similarly, recent studies in adjacent domains, such as driver emotion recognition, have shown that hybrid architectures combining an improved Faster R-CNN with transfer learning on a NasNet-Large CNN can substantially boost recognition accuracy across multiple benchmark datasets22. Such findings reinforce the versatility and robustness of hybrid CNN-based frameworks in handling complex spatiotemporal recognition challenges.

The model was tested on datasets with limited variation and demonstrated significant performance improvements over non-attention-based architectures. In parallel, author23 introduced a novel dataset named Ego-SLD, which consists of egocentric video recordings obtained using wearable devices. This dataset aims to simulate real-life scenarios where gestures are performed from a first-person perspective, providing valuable context often missing in third-person viewpoints. Their CNN-LSTM-based framework successfully used the egocentric cues for improved recognition; however, the system faced persistent challenges such as camera jitter, synchronization lags, and background noise. These issues highlight the practical difficulties associated with real-world deployment of hybrid SLR systems. Despite these limitations, the combination of spatial and temporal modeling remains one of the most effective strategies for achieving accurate and responsive gesture recognition, particularly when enriched with contextual and viewpoint-specific information23.

Meanwhile, swarm intelligence algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for optimizing complex machine learning models, and among them, Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) has demonstrated notable effectiveness in the context of sign language recognition (SLR). Inspired by the social hierarchy and hunting strategies of grey wolves in nature, GWO excels at balancing exploration and exploitation in high-dimensional search spaces17. This makes it particularly useful for tasks like feature selection, parameter tuning, and model configuration, where traditional grid or random search approaches often fall short. In SLR applications, where input data are often high-dimensional and contain redundant or noisy features, GWO helps streamline model performance by intelligently selecting only the most informative attributes. For instance, Author17 proposed a notable adaptation of the standard GWO called AEGWO-Net as discussed earlier, building on this, Author24 also applied swarm intelligence algorithm with 3D Resnet-LSTM by using it to fine-tune architectural hyperparameters in CNN. Their meta-optimization approach not only improved classification accuracy but also led to faster convergence during training. Despite its strengths, a common limitation of swarm intelligence in such applications is its reliance on static optimization targets and sensitivity to initialization conditions, which may hinder its performance when applied to gesture recognition tasks with high temporal variability. Nonetheless, these studies collectively highlight the significant role that GWO optimization can play in building adaptive and high-performing SLR systems25.

On the other hand, incorporating semantic information into gesture recognition models has become increasingly important, especially in tasks that require a deeper understanding of gesture intent and linguistic meaning26. Traditional visual-based SLR systems often rely solely on pixel-level or motion-based representations, which, while effective for isolated sign classification, tend to underperform when context or semantic disambiguation is needed. To address this, researchers have started integrating pre-trained word embedding models such as GloVe and BERT into their recognition pipelines27. These models capture semantic relationships between words and can be used to enrich gesture representations by aligning them with their linguistic counterparts. For example, gestures that may appear visually similar but carry different meanings in different contexts can be better differentiated when augmented with semantic embeddings. For instance, author20, in their work on the NationalCSL-DP dataset, experimented with embedding gesture labels using word vectors, which led to improved accuracy for signs with overlapping visual features. This integration enabled the model to use both visual cues and semantic distances, resulting in more robust performance. Likewise, advances in related fields such as sentiment analysis have shown that multi-objective manifold representation frameworks combining deep global features, local manifold representations, and self-attention can significantly enhance contextual understanding of textual data28. These insights reinforce the potential of combining visual learning with semantic understanding, opening new paths for real-time gesture-to-text systems and automatic sign language translation29. However, challenges remain in aligning gesture data with correct linguistic constructs across different sign languages due to cultural and syntactic variations.

Another emerging area in sign language recognition is signer-independent modeling, which addresses the variation in gesture style, speed, body proportions, and motion range among different individuals30. While many SLR systems perform well in intra-signer conditions, their accuracy typically degrades significantly in cross-signer evaluations. This poses a serious limitation for deploying SLR technologies in the real world, where systems must generalize across users with no prior training data. To tackle this, researchers31 have explored various strategies including domain adaptation, data augmentation, and feature normalization techniques. Also, some recent models use domain adversarial training to learn signer-invariant features, ensuring that the latent representations remain consistent regardless of the signer. Others apply pose estimation and skeletal tracking to focus on the geometric properties of hand and arm movement, which are less affected by individual appearance or background clutter. Studies such as32,33 have showed improvements by fusing RGB and pose stream inputs, effectively filtering out signer-specific visual noise. However, signer-independent recognition still remains an open research problem, particularly when gestures are recorded in unconstrained environments with occlusions, varying lighting, and cluttered backgrounds.

Thus, multimodal fusion has emerged as a powerful approach to enhancing the robustness and expressiveness of sign language recognition systems. Unlike unimodal systems that rely only on RGB frames, multimodal frameworks integrate complementary modalities such as depth data, skeletal joints, optical flow, and even facial expressions to form a richer representation of sign language gestures34. For instance, author35 combined pose flow and self-attention mechanisms to capture both manual and non-manual gesture components, achieving superior accuracy on the AUTSL dataset. Similarly, 3D CNNs and LSTM architectures have been used to process sequences of skeleton joint positions derived from tools like OpenPose and MediaPipe, which are particularly effective in low-light or cluttered environments36. Depth sensors and infrared-based data further reduce dependency on lighting conditions, making models more robust across settings. Also, recent trends showed promise in using Transformer-based multimodal attention to learn interdependencies across modalities rather than just concatenating them37. However, challenges exist in terms of data synchronization, sensor availability, and computational overhead. Additionally, the fusion process must be intelligently managed naïvely combining modalities can introduce redundancy or noise38. Therefore, GWO and other metaheuristic optimization techniques can aid here by automatically learning optimal fusion weights or choosing the most informative modality combinations for a given recognition task39. This not only reduces model complexity but also ensures adaptability across different hardware setups, paving the way for scalable, real-time, and user-friendly SLR systems.

Several studies have used Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) variants for gesture recognition and related tasks40. PCA-IGWO41 applies an Improved GWO to select optimal principal components, enhancing classification accuracy but relying on shallow feature extraction methods. KPCA-IGWO42 builds on this by introducing nonlinear transformations via Kernel PCA, yet it remains detached from deep learning frameworks and temporal modeling. GWO-CNN43 leverages GWO for tuning convolutional parameters such as kernel size and learning rate in a CNN architecture, achieving strong performance on static gestures but lacking support for temporal dynamics. AEGWO-NET44 enhances GWO with adaptive coefficients for binary feature selection and shallow architecture optimization; however, it does not support deeper or hybrid networks like CNN-Transformers. Similarly, Hybrid SVM-GWO45 optimizes SVM parameters using GWO, but its scalability and suitability for large-scale spatial–temporal tasks remain limited. Unlike these methods, our proposed GWO-CTransNet integrates GWO at the architectural level to tune parameters across both CNN and Transformer modules in an end-to-end fashion, enabling robust performance on dynamic sign language recognition.

The major contributions of recent works are summarized in Table 1 below, and each presents a unique strategy for addressing the diverse challenges of sign language recognition. These studies collectively demonstrate the shift toward deep learning models that integrate optimization, semantic reasoning, and contextual awareness to enable robust, real-world gesture recognition systems.

These recent studies demonstrate the growing trend of combining deep learning with optimization techniques to address the complexities of sign language recognition. Although the hybrid approaches improve performance in terms of accuracy, generalization, and robustness, challenges such as real-time responsiveness, signer independence, and low-resource adaptability remain open areas for future exploration.

Research gaps

A comprehensive analysis of recent literature in sign language recognition reveals significant strides made through the integration of CNNs, Transformers, and optimization algorithms. However, several critical gaps persist. While CNNs effectively capture spatial features, they lack temporal modeling capabilities, and their performance deteriorates under dynamic conditions such as hand occlusions or complex backgrounds. Transformer-based models address temporal dependencies but often require extensive computational resources and large-scale datasets, limiting their scalability in real-time or embedded applications. Furthermore, existing optimization frameworks predominantly focus on feature-level selection or linear hyperparameter tuning. Most of these models apply GWO for static feature selection or as a preprocessing tool rather than integrating it as an adaptive, dynamic component within an end-to-end training pipeline. This limits the exploitation of GWO’s full potential in navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces.

Additionally, few studies have combined GWO with Transformer-based models. There is a lack of research applying GWO to optimize architectural parameters such as attention head counts, embedding dimensions, and dropout configurations in conjunction with CNN-Transformer hybrids. Most hybrid models also overlook the inclusion of semantic embedding layers or contextual linguistic cues, which can significantly improve gesture recognition in ambiguous or low-light scenarios.

System model and problem description

This section introduces the architectural design and operational workflow of the proposed GWO-CTransNet model. By combining convolutional and transformer-based components with Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), the framework effectively extracts spatial–temporal features from dynamic gesture sequences and optimizes hyperparameters automatically. The methodology is organized into five interconnected stages: preprocessing, spatial feature extraction, temporal modeling, hyperparameter optimization, and final classification.

Proposed GWO-CTansNet system model

The architecture of the GWO-CTransNet model, shown in Fig. 1, begins with a pre-processing module responsible for standardizing input data. This includes normalization, resizing of input frames (e.g., to 64 × 64 or 28 × 28 pixels depending on the dataset), and application of augmentation techniques such as flipping, contrast enhancement, and random cropping to introduce variability and mitigate overfitting. Following preprocessing, the CNN-based spatial feature extractor is employed to identify low- and high-level spatial hierarchies in hand gesture images. These extracted features are then passed to a Transformer module, which is designed to model temporal dependencies using self-attention mechanisms. The Transformer captures contextual variations in gesture sequences by constructing semantic embeddings across time steps.

Subsequently, the GWO algorithm iteratively adjusts hyperparameters, optimizing the network’s depth, dimensionality, and learning rate based on fitness values computed from classification performance. Finally, the optimized feature embeddings are passed through a fully connected softmax classifier, which outputs the predicted gesture class. The integration of CNN, Transformer, and GWO into a unified framework enables the GWO-CTransNet model to effectively handle variability in gesture styles, lighting conditions, and hand orientations while ensuring high recognition accuracy and fast convergence.

While recurrent architectures such as GRUs and spatiotemporal 3D CNNs have been traditionally used for modeling dynamic gesture sequences, they often suffer from either vanishing gradient issues or high computational costs. In contrast, Transformer-based self-attention mechanisms can simultaneously model long-range dependencies without recurrence, providing global temporal context even in short ASL clips. This parallelism not only accelerates training but also improves recognition accuracy, especially in noisy or occluded frames.

To offer clarity on the internal composition of the proposed model, Table 2 presents the full architecture of the GWO-CTransNet framework. It details each major component from the input preprocessing and convolutional feature extractors to the Transformer-based encoder and final classifier along with the corresponding hyperparameters discovered through GWO.

The architecture combines two convolutional blocks for spatial encoding, followed by a lightweight Transformer encoder optimized for temporal reasoning. The selected configuration (e.g., 2 attention heads, embed_dim = 206) reflects the outcome of GWO’s hyperparameter search, enabling the model to achieve strong performance with minimal depth, low overfitting, and efficient runtime.

Problem description

The task of dynamic sign language recognition (SLR) involves accurately classifying a temporally ordered sequence of hand gestures into corresponding semantic categories, ideally in real time as mentioned before. Given the complex spatial variations and dynamic temporal dependencies inherent in gesture sequences, this problem necessitates a hybrid approach that can simultaneously capture visual features from individual frames and contextual dependencies across time. In the proposed GWO-CTransNet architecture, this is achieved by integrating convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for spatial encoding, Transformer encoders for temporal modelling, and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for adaptive hyperparameter tuning.

Let a gesture sequence be defined as G = {g1, g2,, gk} where each frame gi ∈ ℝ{H×W×C} represents an RGB image with height H, width W, and channel C. Each frame in the sequence is first passed through a CNN module to extract a spatial feature vector:

The resulting set of feature vectors F = {f1, f2, …, fk} is then input into a Transformer encoder to model temporal relationships using multi-head self-attention:

here θT denotes Transformer-specific parameters including attention head count, positional encoding strategy, and hidden layer dimensions. While the CNN and Transformer modules handle feature extraction and sequence modeling respectively, their overall performance is highly dependent on the choice of hyperparameters.

To automate the selection of these hyperparameters, we define an optimization problem using the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm. Let the set of tuneable parameters be:

Each candidate solution (i.e., each “wolf” wᵢ) in the GWO population encodes a configuration of the parameter set Θ. The fitness of each candidate is evaluated based on validation performance using a composite fitness function:

Here, α, β, γ ∈ [0, 1] are scalar weights that balance the trade-off between accuracy maximization, training loss minimization, and computational efficiency. Additionally, the optimization is subject to resource constraints:

These constraints ensure that the selected configuration is suitable for real-time and memory-constrained deployment environments. This formalization enables GWO-CTransNet to dynamically adapt its parameters for both accuracy and efficiency across varying datasets and hardware setups.

Proposed GWO-CTransNet algorithm

The proposed GWO-CTransNet algorithm is designed as an adaptive, hybrid deep learning model for dynamic sign language recognition. It integrates three primary components: CNN-based spatial feature extraction, Transformer-based temporal attention modeling, and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for meta-learning and hyperparameter tuning. In this section, we present a detailed step-by-step description of the proposed algorithm, followed by the associated mathematical formulation and pseudocode representation.

The algorithm takes a gesture sequence G = {g1, g1, …, gk}, where each frame gᵢ ∈ ℝ{H×W×C} corresponds to a normalized RGB image of dimensions H × W × CH. The preprocessing pipeline applies resizing, normalization, and augmentation to standardize the input. Each gesture frame is then independently passed through a CNN encoder to extract spatial features:

The resulting set of feature vectors F = {f1, f2, …, fk} is then fed into the Transformer encoder, which models temporal dependencies through multi-head attention:

here θT includes hyperparameters such as attention head count, embedding dimensions, and encoder depth. The temporal encoding zi is further enriched by concatenating it with semantic embeddings Esem, if available, to enhance contextual learning:

The final representation zi′ is passed to a fully connected softmax classifier for gesture prediction:

To automatically fine-tune the architectural and training parameters, the GWO algorithm is used. The hyperparameter search space Θ includes CNN kernel sizes, number of Transformer heads, learning rate, dropout rate, and embedding size. Each solution wi in the GWO population represents a candidate configuration from Θ, and its fitness is evaluated through a weighted multi-objective function:

This optimization is conducted under resource-aware constraints:

where α, β, γ ∈ [0,1] are tunable weights that control trade-offs between accuracy, training stability, and computational efficiency.

The workflow of the proposed algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1, which outlines the iterative process of population initialization, fitness evaluation, position update using alpha–beta-delta hierarchy, and convergence to the optimal hyperparameter set Θ. The final model is retrained using this optimal configuration to ensure performance generalization.

Hyperparameter settings and Grey Wolf Optimization

The Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm was chosen for this work due to its simplicity, robustness, and strong convergence behavior in continuous optimization problems. Unlike traditional grid or random search, GWO effectively balances exploration and exploitation through a social hierarchy modeled on grey wolf pack behavior. In the context of hyperparameter tuning for neural networks, this capability is particularly valuable due to the large and non-convex search spaces involved. Moreover, compared to other meta-heuristics such as PSO or GA, GWO has fewer hyperparameters to tune and demonstrates better stability across runs. Its leadership-driven update mechanism enables faster convergence toward optimal configurations while minimizing computational overhead. This makes GWO especially suitable for resource-constrained environments and time-limited training scenarios.

In the context of the proposed GWO-CTransNet framework, key hyperparameters encompass the kernel sizes of convolutional layers, dropout rates, learning rate, attention head count in the Transformer module, embedding dimensions, and the size of fully connected output layers. Instead of relying on conventional methods such as manual tuning or exhaustive grid search, which are computationally expensive and often suboptimal, this study leverages the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm to identify the optimal set of hyperparameters. GWO is particularly suited to this task due to its nature-inspired balance between exploration and exploitation during the search process.

Meanwhile, GWO is applied as an offline pre-training optimization strategy. Before the model training begins, a population of grey wolves is initialized to search the hyperparameter space. Once the optimal combination is selected based on validation performance, the model is trained using the best set of parameters. This approach avoids the computational overhead of online optimization and ensures consistent training behavior across experimental runs.

In this framework, each grey wolf represents a candidate solution comprising a unique combination of hyperparameter values. The quality of each configuration is evaluated using a multi-objective cost function that considers validation accuracy, training loss, and computational cost. The wolves are hierarchically divided into alpha (Gα), beta (Gβ), delta (Gδ), and omega (Gω) based on their fitness scores. The wolves iteratively update their positions using the influence of the top-performing wolves. This mechanism is formally captured by the following equations:

Here, A and c are coefficient vectors that control the step size and direction of updates. They are computed as A = 2a·r1—a and c = 2r2, where r1 and r2 are random vectors in [0, 1], and a is a linearly decreasing parameter from 2 to 0 across iterations. When ∣A∣ > 1|, the algorithm favors exploration of new search regions, while ∣A∣ < 1 focuses on exploitation around the best-known solutions. This dynamic adjustment enables the optimizer to effectively navigate the high-dimensional space of hyperparameter configurations.

To further enhance convergence behavior and reduce stagnation, a self-adaptive version of GWO is used. This variant introduces a learning factor ρ ∈ [0, 1] , updated over time to control the influence of current versus historical best behaviors. The self-adaptive coefficients are calculated as:

This formulation enables a smooth transition from wide-ranging search behavior to focused fine-tuning as optimization progresses. The learning process is not only adaptive but also robust across datasets with varying spatial and temporal complexity.

The motivation for introducing a self-adaptive mechanism in GWO arises from common limitations in standard GWO, such as stagnation in local optima and premature convergence. By incorporating a dynamic learning factor ρ that evolves over iterations, our variant balances exploration and exploitation based on historical behavior rather than relying solely on randomization. This adaptive control enables smoother convergence and reduces sensitivity to initial population settings. Empirical convergence plots further support that our variant outperforms standard GWO in both speed and accuracy as it can be seen from Fig. 15. Thus, this modification enhances robustness across diverse datasets and improves overall optimization efficiency.

Meanwhile, Fig. 2 illustrates a conceptual overview of how candidate solutions (wolves) explore the hyperparameter space during optimization. Unlike binary-encoded genetic algorithms, GWO uses real-valued vectors to represent each wolf’s position. Each dimension of the vector corresponds to a specific hyperparameter: continuous parameters like learning rate and dropout are sampled from a defined numeric range, while categorical parameters such as kernel size, attention head count, and embedding dimensions are chosen from predefined discrete sets. For example, a wolf might represent the configuration (kernel size = 5, dropout = 0.3, embed_dim = 128), and its fitness is evaluated by training a model with those settings and computing validation accuracy. The wolves update their positions using the leadership hierarchy rules of the GWO algorithm, ensuring an adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation across the search space.

This encoding strategy enables GWO to perform holistic and fine-grained hyperparameter optimization without relying on binary abstraction or manual tuning. By embedding GWO in the model training pipeline, GWO-CTransNet dynamically adapts to dataset-specific characteristics, yielding strong generalization performance with minimal trial-and-error. This makes the framework especially effective in sign language recognition tasks that require precision and efficiency across variable input sequences.

Evaluation metrics

To rigorously assess the predictive performance of the proposed GWO-CTransNet model in dynamic sign language recognition tasks, a suite of widely accepted evaluation metrics is employed. These metrics were chosen to capture not only overall accuracy but also robustness against class imbalance, sensitivity to relevant gestures, and confidence in prediction probabilities. The primary metric, classification accuracy, is calculated as the proportion of correct predictions relative to the total number of instances:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Although accuracy is a strong general indicator, it may present a skewed picture when the dataset contains uneven class distributions—a common scenario in real-world sign language datasets.

To account for this, precision, recall, and F1-score are also utilized. Precision measures how many of the predicted positive labels are actually correct:

Conversely, recall evaluates how many of the actual positive labels are correctly identified:

The F1-score combines both precision and recall into a single harmonic mean, particularly useful in scenarios where both false positives and false negatives carry significant penalties:

This metric is especially useful in evaluating systems where both false positives and false negatives are costly, such as real-time gesture recognition.

For a more nuanced and threshold-independent evaluation, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) is computed. AUC reflects the model’s ability to distinguish between gesture classes and is especially critical in imbalanced and multiclass classification settings. A value closer to 1 indicates a superior model that performs well across all thresholds.

In parallel, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is included to provide a balanced, correlation-based measure of performance. It is given by:

MCC is particularly effective for assessing performance across imbalanced datasets and yields a value between − 1 and + 1, where + 1 denotes perfect classification, 0 implies random performance, and − 1 indicates total disagreement.

Finally, cross-entropy loss is used as the training objective. It quantifies the divergence between predicted class probabilities and actual ground truth distributions, encouraging the model to minimize uncertainty during classification:

here yi is the true label (1 for the correct class, 0 otherwise) and \(\hat{y}_{i}\) is the predicted probability for that class. Minimizing this loss ensures the model learns more confident and accurate mappings between gesture sequences and their semantic labels.

Experimental environment and result analysis

This section details the experimental configuration, dataset preparation, and performance evaluation of the proposed GWO-CTransNet model. Through systematic testing on benchmark sign language datasets, we assess the model’s accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency using a range of established evaluation metrics.

Experiment environment and parameter settings

The entire model was implemented in Python 3.7 using deep learning libraries such as PyTorch and scikit-learn. Experiments were executed on a 64-bit machine equipped with an Intel® Core i5 CPU and 16 GB RAM. The overall architecture of the proposed GWO-CTransNet framework is illustrated in Fig. 3, which describes the sequential stages from input acquisition to final performance evaluation. This pipeline integrates spatial feature extraction, temporal modeling, semantic encoding, and hyperparameter optimization, combining them into an end-to-end gesture recognition system optimized using the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO).

The process begins with input image acquisition, which involves either static grayscale gesture images like ASL MNIST or RGB-based dynamic sequences such as ASL Alphabet. These input samples are initially processed through a Transformer module, where the spatial structure of each gesture is captured and embedded into a high-dimensional representation. Simultaneously, temporal dependencies are modeled by encoding frame-level transformations, particularly useful for datasets containing video sequences. Once spatial and temporal features are extracted, the training dataset is split from the overall input for model learning. These features are then passed through the semantic embedding layer, which ensures dimensional uniformity and semantic coherence across gesture representations. The embedded vectors are subsequently fed into the GWO optimization module, where an initial population of hyperparameter sets comprising embedding dimension, attention heads, Transformer depth, and learning rate is randomly initialized.

Each candidate solution in the GWO population is evaluated based on its fitness, which is determined by the classification accuracy of the resulting model. The optimizer ranks the grey wolves solutions and updates the positions of the α, β, and δ wolves using GWO’s social hierarchy and hunting behavior-inspired rules. This iterative search continues until a predefined stopping criterion is met, typically based on convergence or maximum iterations. Once the best hyperparameters are identified, the final model is trained on the optimized feature set and evaluated on the testing dataset. A standard CNN classifier is used for this phase to ensure effective prediction while minimizing computational overhead. The output class labels are then compared with ground-truth annotations to compute key performance metrics including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, AUC, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

As mentioned, the integration of GWO into the model optimization process enhances convergence speed, avoids local minima, and improves generalization across diverse gesture categories. The modular structure illustrated in the diagram ensures flexibility, allowing the framework to be adapted to multiple sign language datasets with minimal reconfiguration.

Dataset description

The first dataset used in this study is the American Sign Language (ASL) dataset, which serves as a benchmark for evaluating gesture recognition systems in English-based sign communication. The dataset includes thousands of labeled video samples representing dynamic sign gestures spanning the ASL alphabet and selected vocabulary. Each video sequence in the dataset comprises RGB frames captured under varying conditions to simulate real-world diversity in lighting, hand orientation, and background complexity. The dataset encompasses more than 25 gesture classes with approximately 150–300 samples per class, ensuring class balance and representational diversity as it can be seen from Table 3. The videos are recorded at an average resolution of 64 × 64 pixels and are resized during preprocessing to ensure model compatibility and training stability. Furthermore, the dataset includes both static and motion-intensive signs, enabling the model to capture temporal dynamics essential for accurate gesture classification. Data augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, contrast normalization, and random cropping are applied to increase variability and reduce overfitting during training. The ASL dataset is divided into training, validation, and testing subsets with a typical split of 70%, 15%, and 15%, respectively. This dataset offers a standardized platform for evaluating the spatial–temporal modeling capabilities of the proposed GWO-CTransNet architecture, especially in handling signer-independent generalization and sequence-level gesture transitions.

In addition to the ASL Alphabet dataset, the ASL MNIST dataset was utilized to further evaluate the model’s robustness and generalization across different styles of American Sign Language representations. The ASL MNIST dataset is a publicly available collection that consists of grayscale images representing static hand signs corresponding to the 26 letters of the English alphabet, formatted similarly to the popular MNIST digit dataset. Each image in the dataset has a resolution of 28 × 28 pixels and is centered with uniform padding to facilitate efficient recognition. Unlike the ASL Alphabet dataset, which includes RGB dynamic gesture sequences with complex visual features, ASL MNIST provides simplified and normalized samples that focus on character-level hand shape recognition. The dataset contains over 27,000 labeled instances distributed evenly across all 26 classes, making it suitable for evaluating classification consistency under reduced input complexity. During preprocessing, the images were resized and normalized to match the model’s expected input dimensions. To simulate real-world variations, basic data augmentation techniques such as brightness jittering, small rotations, and horizontal flipping were applied. Both datasets (ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST) were split into training, validation, and testing subsets using a 70%-15%-15% ratio. This dual-dataset approach enables comprehensive evaluation of the GWO-CTransNet framework on both realistic, dynamic hand gesture videos and static, character-based gesture images, enhancing its applicability in diverse real-world scenarios.

Gesture recognition and performance results

The effectiveness of the proposed GWO-CTransNet framework in gesture recognition was rigorously evaluated through experiments conducted on two benchmark datasets: ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST. These experiments were designed to measure the model’s ability to learn discriminative patterns from both dynamic and static hand gestures, under various configurations optimized by Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO). The GWO mechanism dynamically adjusted key hyperparameters, including the embedding dimension, number of attention heads, Transformer depth, and learning rate, enabling the model to explore a diverse parameter space and converge towards optimal performance.

A total of several configurations was tested, and their training outputs were logged to observe performance consistency. One of the top-performing configurations embed_dim = 206, heads = 2, depth = 1, learning_rate = 0.00121 demonstrated substantial convergence capability with only two training epochs, reducing the loss from 0.8751 to 0.1240, and attaining an impressive accuracy of 95.78%. These results are illustrated in Fig. 4, which showcases training logs for various configurations, highlighting the evolving accuracy and confirming that the GWO meta-heuristic was successful in identifying optimal architectural and learning parameters.

Further evidence of learning robustness was observed in the full 10-epoch training run using an extended configuration, where the model reached an exceptional accuracy of 99.40% with a final loss of just 0.0195. This is clearly showed in Fig. 5 (for ASL Alphabet) and Fig. 6 (for ASL MNIST), which present the training loss and accuracy plots over epochs. The loss curve shows a rapid decline during the initial epochs, stabilizing at minimal values in later stages, while the accuracy curve shows a steep ascent toward near-perfect classification. The close alignment between training and validation performance also indicates that the model generalizes well, without overfitting.

To further substantiate the quantitative evaluation, a comprehensive classification report was generated for the ASL Alphabet dataset. As shown in Fig. 7, most classes achieved precision, recall, and F1-score values above 0.99. Particularly, the model achieved perfect classification (1.000) for multiple gesture classes including ‘I’, ‘J’, and ‘O’. Even for relatively complex gestures such as ‘W’, ‘V’, and ‘L’, the F1-scores remained exceptionally high above 0.98. The macro average and weighted average values for all evaluation metrics also stood at 0.9975, reinforcing the stability and accuracy of predictions across class imbalances. This level of consistency is vital in sign language recognition (SLR) systems, where even minor classification errors can significantly alter the semantic interpretation of communication.

The qualitative performance of the model was validated through real-time gesture predictions, where hand landmark extractions were overlaid on the frame using MediaPipe. Despite challenging conditions such as background clutter and varying lighting, the model correctly predicted gestures such as ‘C’, ‘D’, and ‘nothing’ across multiple scenarios. These outputs validate the model’s spatial–temporal alignment, achieved through CNN-Transformer synergy, and its robustness to environmental noise due to GWO’s effective regularization of model parameters.

In terms of comparative analysis, the proposed GWO-CTransNet model was evaluated against several baseline architectures to highlight its performance gains across multiple key metrics. To ensure statistical validity and reproducibility, all models were trained and evaluated over 30 independent runs using different random seeds. Performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were reported as mean ± standard deviation, and their results are presented in Table 4. The low standard deviations confirm the stability and robustness of the proposed method across multiple trials.

The baseline CNN-only model achieved a respectable accuracy of 92.13% ± 0.27, with corresponding precision, recall, and F1-score values slightly above 91%. Incorporating a Transformer backbone without Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) led to an accuracy improvement of 94.22% ± 0.19, indicating that temporal attention mechanisms provide added value over purely convolutional designs. The CTransNet model, which integrates CNN and Transformer components but excludes GWO-based optimization, further enhanced performance, yielding an accuracy of 96.07% ± 0.14 and a balanced F1-score of 95.89% ± 0.16. These results clearly underscore the benefits of temporal-spatial feature fusion in gesture recognition.

However, the most significant performance enhancement was observed with the full GWO-CTransNet framework. This configuration outperformed all baselines, achieving an outstanding accuracy of 99.40% ± 0.11, with precision of 99.36% ± 0.08, recall of 99.27% ± 0.09, F1-score of 99.31% ± 0.07, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.988, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.992. These metrics collectively reflect the system’s robust predictive power, low false-positive rates, and generalization across gesture categories.

This empirical superiority is further visualized in Fig. 8, which plots the model’s training dynamics over 10 epochs. The left subplot (Loss) demonstrates a steep and consistent decline in loss values from approximately 0.8 down to 0.02 indicating rapid convergence and minimal overfitting. Simultaneously, the right subplot (Accuracy) shows a steady climb, with the model surpassing 95% accuracy by the second epoch and approaching 99.40% by the tenth. The near-plateau shape of the curve toward the later epochs indicates not only convergence but also model stability, an outcome largely attributed to GWO’s effective hyperparameter selection.

The concurrent decline in loss and rise in accuracy corroborates the quantitative results in Table 4 and reflects the optimized learning behavior fostered by the GWO algorithm. This synergy between the optimization layer (GWO), temporal-spatial architecture (CTransNet), and the training strategy establishes GWO-CTransNet as a highly capable model for real-time gesture recognition.

To further validate the robustness of the model and rule out potential data leakage, the ASL Alphabet dataset was split usin 70:15:15 train-validation-test ratio, with signer-independent separation to ensure no overlap between individuals across sets. Each image was preprocessed by resizing to 64 × 64 pixels, grayscale conversion, and histogram equalization to normalize lighting conditions.

Figure 9 presents the confusion matrix for all 29 ASL gesture classes. As shown, GWO-CTransNet demonstrates high per-class accuracy, with the majority of predictions along the diagonal. Minimal misclassifications are observed, primarily among visually similar gestures such as ‘M’ and ‘N’. This matrix confirms that the model’s exceptional performance (99.4% accuracy) is not skewed by class imbalance or data leakage and maintains consistent prediction quality across the full gesture spectrum.

Real-time gesture recognition output

The real-time applicability of the proposed GWO-CTransNet model was rigorously evaluated through live gesture detection experiments, expanding the assessment beyond static classification metrics. While earlier sections established the model’s quantitative robustness across standard evaluation measures, this segment focuses on the model’s practical performance under dynamic and visually variable conditions. The qualitative results provide an essential dimension to validating the generalizability and responsiveness of the system in real-world usage scenarios.

To assess gesture recognition fidelity in real-time environments, GWO-CTransNet was deployed on a standard webcam feed for both controlled and semi-uncontrolled settings. The architecture integrated MediaPipe’s landmark-based hand tracking pipeline for joint localization, which produced 21 keypoints per detected hand. These keypoints were used to draw skeletal structures over the input frames, serving as an interpretable bridge between raw image features and high-level semantic predictions. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the model successfully identified the letter ‘C’ from a single right-hand gesture. Despite slight variations in hand orientation and environmental lighting, the model accurately mapped joints and predicted the correct class with high certainty. This illustrates the strength of the CNN-Transformer backbone in capturing discriminative spatial and temporal features, while GWO’s role in hyperparameter optimization ensured enhanced generalization in variable visual conditions.

Similarly, Fig. 11 shows the detection of the ‘nothing’ gesture under low-contrast lighting and complex background elements. Even in the presence of reflective surfaces and shadows, the model’s prediction remained stable. This resilience can be attributed to the optimized attention mechanisms and dropout rates learned through GWO, which mitigated the overfitting that typically hampers detection in noisy inputs. These findings are consistent with earlier results discussed in Sect. 5.3, where high precision and recall values were reported for similar gestures.

Perhaps the most compelling demonstration of the model’s real-world potential is its performance in recognizing multiple gestures concurrently. Figure 12 presents an instance where both left and right hands are captured within the same frame, each displaying distinct gestures—‘D’ and ‘C’, respectively. The model not only accurately recognized both gestures but also maintained temporal coherence across frames, rendering a live textual output beneath the video feed. Although occasional misclassifications (e.g., transient detection of ‘Q’ due to gesture overlap) were observed, they were minimal and quickly corrected in subsequent frames. This emphasizes the model’s robustness in temporal modeling, particularly when handling rapid gesture transitions or simultaneous gesture streams.

In terms of system responsiveness, GWO-CTransNet achieved processing speeds ranging between 1–4 frames per second on a CPU-only machine, without GPU acceleration. Despite the modest hardware, the system maintained fluid real-time interaction, indicating that the model is lightweight and optimized for deployment in resource-constrained environments. This further strengthens its applicability for assistive communication systems, educational interfaces, and human–computer interaction platforms, where both latency and accuracy are critical.

Taken together, these real-time detection outputs corroborate the quantitative metrics discussed earlier and reinforce the effectiveness of the GWO-CTransNet model. The successful integration of semantic embedding, Transformer-based modeling, and GWO-driven parameter optimization culminates in a gesture recognition system that is not only accurate but also highly adaptable to real-world operational contexts.

Computational performance

The computational efficiency of the proposed GWO-CTransNet framework was systematically analyzed across both the ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST datasets as mentioned before. This evaluation encompassed three core aspects: training time convergence, the computational cost of the GWO optimizer, and the overall algorithmic complexity in terms of Big O notation. All experiments were conducted on a modest hardware setup an Intel® Core i5 64-bit CPU with 16 GB of RAM and no GPU acceleration simulating a real-world deployment scenario in environments where computational resources is limited.

From a training efficiency standpoint, GWO-CTransNet demonstrated rapid convergence with relatively shallow architectures. For example, on the ASL Alphabet dataset, one optimized configuration with embed_dim = 206, heads = 2, depth = 1, and lr = 0.00121 achieved 95.78% accuracy in just two epochs. Extended training across 10 epochs further improved performance, culminating in a peak accuracy of 99.40% with a final loss of 0.0195. This convergence is visualized in training plots in Fig. 7, where both the loss curve and accuracy curve plateau early, indicating stable optimization dynamics. Similar trends were observed on the ASL MNIST dataset, where accuracy improved from 57.01 to 98.07% within 10 epochs, and training loss declined from 1.3384 to 0.0590. These results affirm not only the effectiveness of GWO in navigating the hyperparameter search space but also the model’s computational parsimony in learning from structured gesture data.

In terms of time complexity, GWO-CTransNet can be divided into three components: the CNN-based spatial feature extractor, the Transformer module for temporal representation, and the GWO optimizer. The CNN has a typical complexity of O(n·d2·k2), where n is the number of layers, d is the input spatial dimension, and k is the kernel size. The Transformer module, which processes T time steps with d embedding size and h attention heads, exhibits a complexity of O(T2·d) due to the self-attention mechanism. This quadratic scaling in sequence length is one of the dominant factors in runtime but remains manageable due to the limited frame count per gesture (typically < 30). The GWO optimizer iteratively updates a population of m grey wolves across g generations, where each position update requires fitness evaluation through model training. The complexity of GWO can thus be approximated as O(m·g·f), where f is the cost of evaluating the objective function in this case, classification accuracy computed via training epochs.

When integrated, the overall time complexity of the training pipeline becomes:

where E represents the number of epochs and the first term encapsulates model training, while the second captures GWO-driven tuning. However, since GWO typically converged within fewer than 10 generations and used a small population size (m = 10), the optimization overhead remained tractable. This contrasts with grid search or random search, which often scale exponentially in high-dimensional spaces.

In terms of space complexity, the Transformer module contributes significantly due to the attention weight matrices and feed-forward layers, each of which scales with O(T·d + d2). However, by leveraging GWO to select optimal embedding dimensions and depth, memory usage was minimized without sacrificing accuracy. This was evident from training on ASL MNIST, where the model achieved high accuracy with reduced spatial dimensions (28 × 28 input size) and lightweight Transformer depth, thereby maintaining a low memory footprint.

Therefore, these findings demonstrate that GWO-CTransNet achieves an effective balance between computational demand and predictive power. The optimizer rapidly narrows the search space for hyperparameters, the Transformer efficiently captures temporal dependencies, and the CNN ensures compact yet expressive spatial representations.

Comparative analysis

The classification performance of GWO-CTransNet was benchmarked against three established methods PCA-IGWO, KPCA-IGWO, and AEGWO-NET on both the ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST datasets. As shown in Table 5, GWO-CTransNet outperformed all other models across key metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

For the ASL Alphabet dataset, the proposed model attained an exceptional accuracy of 99.40%, which is approximately 1.71% higher than the strongest competing method, AEGWO-NET (97.69%). This performance gain was accompanied by highly consistent values in recall (99.27%), precision (99.36%), and F1-score (99.31%), reflecting the model’s near-perfect generalization and its ability to minimize both false positives and false negatives. These results are particularly significant in gesture recognition, where subtle shape variations often challenge classifier robustness as it can be seen from Fig. 13. The superior performance of GWO-CTransNet can be attributed to its Transformer-based temporal encoding and the dynamic hyperparameter tuning facilitated by GWO, which effectively captures sequence context and avoids suboptimal local minima.

In the ASL MNIST dataset, although the gap in performance narrows due to the relatively simpler nature of static grayscale gestures, GWO-CTransNet still achieved a competitive accuracy of 98.07%, slightly trailing behind AEGWO-NET’s 98.26%. However, in terms of precision (97.33%) and F1-score (97.17%), GWO-CTransNet demonstrated stronger consistency, suggesting better class discrimination even when confronted with ambiguous hand shapes. These results indicate that while AEGWO-NET slightly outperforms in raw classification, GWO-CTransNet maintains better balance in precision-recall tradeoffs, which is crucial in real-time applications where overconfident misclassifications can have usability implications.

Meanwhile, to further analyze performance under class imbalance conditions, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) was used as a supplementary metric. The MCC score considers all elements of the confusion matrix and is ideal for evaluating classifier reliability. Your GWO-CTransNet model achieved the highest MCC in both ASL Alphabet (0.988) and ASL MNIST (0.971), as highlighted in Fig. 14 below.

These MCC scores not only exceed those of PCA-IGWO and KPCA-IGWO but also marginally surpass AEGWO-NET, affirming that the proposed model is not only accurate but also statistically consistent across imbalanced and challenging gesture classes.

Furthermore, Area Under the Curve (AUC) values for GWO-CTransNet reached 0.992 (ASL Alphabet) and 0.987 (ASL MNIST) as it can be seen from Fig. 15, confirming its high separability of positive vs. negative instances. The high AUC reinforces the model’s ability to correctly rank predictions and minimize false alarms. This attribute is critical in practical settings, such as sign language translation tools, where reliable output ranking determines real-time user confidence.

To further evaluate the generalizability and competitiveness of the proposed GWO-CTransNet architecture, a comprehensive comparison was conducted against several recent and widely adopted sign language recognition models. Table 6 presents a detailed breakdown of performance metrics including Accuracy, F1-Score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and Area Under the Curve (AUC) across both the ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST datasets. The baseline methods selected for comparison include HOG-GA-MLP, LBP-GA-SVM, GWO-Rough Set-Naïve Bayes, PSO-CNN, GWO-CNN, and AEGWO-NET-ANN. Each of these methods has been evaluated using consistent metrics, offering a fair comparison across diverse modeling paradigms ranging from traditional feature-engineering-based pipelines (HOG, LBP) to hybrid evolutionary and deep learning models (GWO, PSO, AEGWO).

Across datasets, GWO-CTransNet consistently surpasses ASL alphabet benchmark models. For the ASL Alphabet dataset, models such as PSO-CNN and GWO-CNN demonstrate high accuracy of 96.45% and 98.42% respectively; however, the proposed GWO-CTransNet outperforms these with a peak accuracy of 99.40%, an F1-score of 99.31%, an MCC of 0.988, and an AUC of 0.992. These results indicate not only high classification accuracy but also excellent balance between precision and recall and strong agreement between predicted and true classes.

In the ASL MNIST dataset, a similar trend emerges. GWO-CNN and AEGWO-NET perform well, with GWO-CNN reaching 99.83% accuracy. Nevertheless, GWO-CTransNet maintains comparable or superior performance, matching or exceeding these results particularly in MCC and AUC, highlighting its robustness in both binary and multiclass settings, and its ability to maintain consistency across varied input distributions.

Therefore, the exceptional performance of GWO-CTransNet can be attributed to several architectural and algorithmic decisions. The CNN layers capture fine spatial nuances, while the Transformer encoder models temporal dependencies more effectively than recurrent networks. More importantly, GWO’s role in hyperparameter tuning ensures that the model is optimally configured for each dataset, avoiding manual guesswork and enabling rapid convergence. By searching across embedding sizes, dropout rates, and learning rates, GWO aligns the model structure with the dataset’s complexity. This automated adaptation is especially beneficial in tasks like sign language recognition, where gesture styles and frame rates vary significantly. The synergy between learning architecture and metaheuristic optimization is the core reason for the model’s superior performance.

While GWO-CTransNet achieves high accuracy, its current inference speed (1–4 FPS on CPU) poses challenges for real-time deployment on low-resource edge devices. To address this, future versions of the model can leverage optimization strategies such as model pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation to reduce computation. Additionally, converting the model to TensorRT or ONNX and deploying with GPU acceleration or dedicated edge AI hardware (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson, Coral TPU) can significantly enhance performance for real-world applications.

Convergence and runtime analysis

To validate the efficiency of GWO as a meta-heuristic optimizer, we conducted a comparative convergence and runtime analysis against three widely used methods: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Grid Search. To ensure a fair comparison, all algorithms were initialized with the same population and their results averaged over 30 independent runs.

As shown in Fig. 16, GWO consistently outperforms the other methods in both convergence speed and final validation accuracy. It exhibits a rapid and stable ascent, reaching near-optimal performance before the 30th iteration and stabilizing around 99.4% accuracy. In contrast, PSO and GA show slower progression and higher variance, while Grid Search, though systematic, converges more slowly and plateaus early due to its discrete and exhaustive strategy.

To complement this output, Table 7 presents the average runtime (in minutes) of each optimizer under the same training environment. GWO achieves the fastest completion time, requiring only 18.4 min on average, while Grid Search takes over 120 min, confirming its inefficiency in high-dimensional search spaces.

These results underscore GWO’s strength in efficiently balancing exploration and exploitation through its adaptive mechanism, including the learning factor ρ in our self-adaptive variant. While runtime can vary depending on hardware and implementation, GWO consistently provides better convergence with lower computational cost, making it a suitable choice for deep neural architecture tuning, particularly in time-sensitive gesture recognition tasks.

Computational complexity analysis

While empirical runtime comparisons offer practical insight, they can be influenced by specific hardware, software environments, and implementation styles. To provide a system-independent evaluation, we analyze the theoretical computational complexity of each optimization method using Big-O notation, capturing their growth behavior relative to population size, number of iterations, and dimensionality of the search space.

Let:

-

N = Population size

-

D = Dimensionality of the search space (number of hyperparameters)

-

T = Number of iterations (generations or steps)

The total complexity primarily depends on the number of fitness evaluations and the cost of updating positions or generating new candidates. The Table 8 below summarizes the asymptotic time complexities of the four optimization techniques used in our comparative study:

Among all, Grid Search scales poorly with increasing dimensions, highlighting the superiority of metaheuristic approaches like GWO for high-dimensional optimization.

Conclusion and future work

This study proposed a hybrid deep learning framework, GWO-CTransNet, designed for dynamic American Sign Language (ASL) gesture recognition. The model integrates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for extracting spatial features, Transformer encoders for capturing temporal dependencies, and the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) for automated hyperparameter tuning. The synergy between these components allows the model to adaptively align its architecture to the complexity of input gestures, resulting in robust classification performance. Evaluations on the ASL Alphabet and ASL MNIST datasets confirm the superiority of GWO-CTransNet over competitive baselines such as PCA-IGWO, KPCA-IGWO, GWO-CNN, and AEGWO-NET. Notably, the model achieved impressive results in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, outperforming traditional optimization methods in both convergence speed and final performance.

To strengthen statistical reliability, we included mean and standard deviation measurements across multiple experimental runs, along with a comparative convergence analysis of GWO versus PSO, GA, and Grid Search. These results demonstrate that our self-adaptive GWO variant not only converges faster (typically under 10 iterations) but also achieves higher stability in optimization. A runtime performance table and accuracy convergence plot have been added to visually emphasize GWO’s efficiency. Furthermore, the limitations of GWO and Transformer architectures have been explicitly acknowledged, including GWO’s vulnerability to premature convergence and random initialization, and the Transformer’s quadratic scaling which can affect memory and runtime in longer input sequences.

In addition to quantitative results, real-time gesture outputs on CPU-only systems (1–4 FPS) revealed the practical limitations for edge deployment. To address this, future work will focus on model compression techniques such as quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation to reduce the computational load without compromising accuracy. Deployment strategies such as exporting to ONNX or TensorRT, and leveraging GPU-based inference on devices like NVIDIA Jetson or Coral Edge TPU, will also be explored. These enhancements aim to make GWO-CTransNet viable for real-time applications such as mobile interpreters, educational tools for the hearing-impaired, and smart environments requiring low-latency gesture control.

Moreover, this framework opens several research directions. Integration of multimodal features such as facial expressions, hand skeletal joints, or depth cues from LiDAR and Kinect sensors could further improve semantic understanding. Cross-lingual generalization is another promising avenue; by extending training to include diverse sign languages (e.g., Bahasa, Arabic, Somali Sign Language), the model can better support a global user base. Additionally, bias and fairness analysis should be conducted to ensure consistent performance across variations in hand shape, skin tone, and lighting conditions. Overall, GWO-CTransNet represents a step toward adaptive, high-performance, and inclusive gesture recognition systems, paving the way for its integration into assistive technologies and human–computer interaction platforms.

Data availability

The data for this study will be available upon request through the corresponding author.

References

Wang, W. et al. CGMV-EGR: A multimodal fusion framework for electromyographic gesture recognition. Pattern Recognit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111387 (2025).

Geng, L., Chen, J., Tie, Y., Qi, L. & Liang, C. Dynamic gesture recognition using 3D central difference separable residual LSTM coordinate attention networks. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104364 (2025).

Hellara, H., Barioul, R., Sahnoun, S., Fakhfakh, A. & Kanoun, O. Improving the accuracy of hand sign recognition by chaotic swarm algorithm-based feature selection applied to fused surface electromyography and force myography signals. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110878 (2025).

Liu, J., Gan, M., He, Y., Guo, J. & Hu, K. Multimodal multilevel attention for semi-supervised skeleton-based gesture recognition. Complex Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-025-01807-x (2025).

Gogoi, P., Karsh, B., Karsh, R. K., Laskar, R. H. & Bhuyan, M. K. Vision-based real-time gesture-to-speech translation for sign language. Procedia Comput. Sci. 258, 2050–2059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2025.04.455 (2025).