Abstract

Modern engineering and scientific computing often requires solving sparse linear systems containing point-block matrix to model multiphysics problems. The space-time parallel method is popular and attractive in fluid dynamics, fitting parallel computers very well. In this paper, we design and implement a parallel, multi-GPU enabled GMRES solver for solving linear systems in the Kronecker product form arising from the domain decomposition based space-time parallel methods. To improve the efficiency of the solver, we also design a set of optimization strategies for Sparse Matrix-Vector Multiplication (SpMV) in Kronecker product form. These include: (1) enhancing the Compute-to-Memory Access Ratio (CMAR) to fully utilize the high bandwidth nature of the GPU during the computation phase and (2) introducing a parallel buffering scheme and a pre-mapping algorithm to enable the use of GPU-Direct for accelerating the communication phase. We conducted experiments on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs and compared the performance of OKP-Solver with the cuSPARSE based implementation. On the V100 platform, the Kronecker product based SpMV computation (\(T_{Kx}\)) achieves speedups of \(2.00\times\), \(1.87\times\), \(1.85\times\), and \(1.91\times\) on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively, while the communication time (\(T_c\)) achieves \(9.18\times\), \(6.82\times\), and \(1.54\times\) on 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively. On the A100 platform, \(T_{Kx}\) achieves speedups of \(1.43\times\), \(1.50\times\), \(1.64\times\), and \(1.64\times\), while \(T_c\) achieves \(8.95\times\), \(5.60\times\), and \(1.62\times\). The overall solver runtime (\(T_{all}\)) achieves speedups of \(1.70\times\), \(3.48\times\), \(3.70\times\), and \(1.82\times\) on V100, and \(1.33\times\), \(3.70\times\), \(3.48\times\), and \(2.28\times\) on A100, for 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many fields of engineering calculations, such as aerospace, simulation of atmospheric ocean currents, and biomolecular simulation, etc., the solution of physical problems usually depends on the solution of sparse linear systems. These problems are described as differential equations or integral equations based on physical laws, and are transformed into the problem of solving a sparse linear equation system in the form of \({\mathbf {A}}{{\varvec{x}}}={{\varvec{b}}}\) through discretization and linearization processes. Linear equations can be solved by direct method or iterative method. The direct method1 is accurate but resource-consuming, making it suitable for small scale problems. The iterative method, by contrast, is efficient and better suited to large scale problems, despite yielding approximate solutions. A commonly used iterative method is Generalized Minimal Residual Method (GMRES) based on Krylov subspaces2.

Modern scientific computing problems often involve high resolutions and strong time dependence. Traditional time-stepping algorithms, due to stability limits, must use very small time steps when solving problems with strong time dependence, which results in high computational costs. In addition, in parallel computing, the number of communications is proportional to the number of time steps, which severely limits the scalability of the algorithm on large scale parallel architectures. To address these challenges, recent space-time parallel computing strategies, which parallelize both the space and time dimensions, have significantly improved computational efficiency. These strategies have shown notable advantages in problems such as heat equations, convection-diffusion equations, and Stokes flows.

Space-time parallel methods can be divided into methods based on multiple shooting3,4,5, methods based on multigrid6,7,8, direct time parallel methods9, and methods based on domain decomposition and waveform relaxation10,11,12,13. This paper conducts research based on methods based on domain decomposition. When solving the numerical solutions of time-dependent partial differential equations, papers14,15 use the finite element method for spatial discretization and the implicit Runge-Kutta method for temporal discretization. By dividing the time intervals, the stage variables are coupled within each time step, resulting in a linear system in the Kronecker product form, which is used to describe and solve the numerical problems of the partial differential equations after temporal and spatial discretization.

The main challenge to solve a spatiotemporal coupling linear system is that it requires increasing computational resources as the number of coupled stages increases. With the fast development of heterogeneous computing, state-of-the-art GPUs, designed for fine-grained data parallelism and high memory bandwidth, can offer substantial computing capabilities for the solve of the numerical system. However, the SpMV in Kronecker product form in this kind of linear systems don’t change the density of the corresponding matrix when the Kronecker product operations are explicitly performed, which makes the issue of scattered memory accesses still exist. Therefore, code migrating from CPUs to GPUs requires detailed algorithm designs and performance optimizations. Motivated by this fact, in this paper, we focus on building a complete framework on the CPU+GPU platform for the solve of the spatial-temporal linear system. The main contributions are as follows:

-

1.

We introduce a parallel framework on multiple GPUs for solving the linear system derived from space-time parallel method based on domain decomposition. Unlike the general scalar matrix format, our work is motivated by the structure of multiphysics problems and thus focuses on the point-block matrix format. The framework uses the generalized minimum residual (GMRES) method as the key solver.

-

2.

We propose an optimized strategy with specified data layouts for the SpMV in Kronecker product form operations in the distributed solver, which effectively improves the Compute-to-Memory Access Ratio (CMAR). However, a major challenge arises from the mismatch in vector data ordering between the computation and communication phases of the solver. To address this challenge, we employ parallel buffering and pre-mapping strategies to ensure efficient data alignment. When combined with GPU-Direct, these strategies substantially reduce the frequency and overhead of host-device and device-device communications.

-

3.

We conducted experiments on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs and compared the performance of OKP-Solver with the cuSPARSE based implementation. The results show that both the computation and communication phases of the solver benefit from notable acceleration, leading to an overall runtime (\(T_{all}\)) speedup of at least \(1.33\times\) across all cases. In terms of GFLOPS, OKP-Solver improves the Kronecker product based SpMV performance by 83.58%, 86.68%, 84.83%, and 91.11% on the V100 platform, and by 45.41%, 50.03%, 64.55%, and 65.68% on the A100 platform, for 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively.

Related work

As a structured linear algebraic tool, the Kronecker product is widely applied in high-performance computing and machine learning due to its favorable computational structure and compact representation capabilities in high-dimensional problems. In the field of machine learning, Tang et al. (2020) utilized dynamic Kronecker product block generation and sparsity optimization techniques to achieve GPU acceleration for graph kernel computations16; Yu et al. (2022) optimizes bilinear pooling via two-level Kronecker product decomposition17; Lin et al. (2024) addresses the missing value problem in learning curve prediction by projecting and selecting observation data joint covariance matrices from latent Kronecker products18.

In the field of high performance computing, Gonon et al. (2024) enhances the GPU computation efficiency of Kronecker-sparse matrix multiplication through a tiling strategy and GPU memory optimization techniques19; Cui et al. (2025) implements tensor product vertex-patch smoothers on GPUs using the characteristics of the Kronecker product structure and fast diagonalization technology, optimizing high-order finite element multigrid computations20; Crews et al. (2022) leverages Python’s CuPy library to achieve GPU acceleration for the discontinuous Galerkin finite element method via tensor product structures21; Jangda et al. (2024) introduces the FastKron framework, adopting row-slice multiplication accumulation, shift buffer optimization, and multi-GPU latency-hiding strategies to significantly improve the computation speed of Kron-Matmul on GPUs22; Jhurani et al. (2013) designs BLAS-like interfaces (TKRON2/TKRON3), optimizes memory layout and shared memory reuse, and proposes efficient GPU algorithms for batched Kronecker products23.

Some works17,18,23 used the properties of Kronecker product to convert the explicit SpMV in Kronecker product form into implicit operations, so as to reduce the number of floating-point operations, thereby improving the computational efficiency.

In contrast to existing research, our study makes two distinct contributions. First, most existing research focuses on specific application scenarios, studying various computational forms of the Kronecker product. Our work focuses on designing a solver for linear systems involving Kronecker products, which arise from a space-time parallel method based on domain decomposition. Secondly, while these studies mainly focus on single-GPU acceleration, we explore the performance and optimization strategies of the proposed solver on multi-GPU platforms.

Background

Kronecker product

Given matrices \({\mathbf {H}}\in \mathbb {R}^{m\times e}\) and \({\mathbf {G}}\in \mathbb {R}^{y\times k}\), then the Kronecker product \({\mathbf {H}}\otimes {\mathbf {G}}\in \mathbb {R}^{my\times ek}\) is defined as:

where \(h_{ij}\) represents the element at the \(i^{th}\) row and \(j^{th}\) column of \({\mathbf {H}}\).

Point-block matrix

Point-block matrices are common in multi-physics problems24,25,26,27, where multiple coupled variables are required to be solved at each grid point. These problems generally result in sparse matrices that are composed of dense blocks each of which represents the coupling feature between the variables locally. For example, in an incompressible flow, each grid point in the computational domain has three velocity components u, v, w and a pressure component p to be solved, and it leads to a point-block matrix with a block size of 4 when the physical variables associating with a grid point are calculated in the coupling method.

Typically storage formats for a point-block matrix are BCSR (Block Compressed Sparse Row) and BCSC (Block Compressed Sparse Column)27 where sparse data is stored in blocks instead of scalars. These formats are widely supported by high-performance computing libraries such as PETSc28, cuSPARSE29, Trilinos30, Intel MKL31 and Hypre32.

Problem definition

We consider the linear system in the Kronecker product form arising from the spatiotemporal coupling algorithm14,15 as:

where \({\mathbf {A}}, {\mathbf {B}} \in \mathbb {R}^{s \times s}\) are dense matrices arising from the temporal discretization with \(s\) denoting the number of time steps, and \({\mathbf {M}}, {\mathbf {L}} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) are point-block matrices with a block size \(b\) from the spatial discretization, \(n\) represents the number of block rows, so that \(N=nb\), \(\tau\) is a constant for time-scaling, and \(\mathcal {U}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\), with a size of \(N\times s\), are the solution and right-hand side vector, respectively.

GPU solver

We show the GMRES(m) method for the solve of Eq. (2) in Algorithm 1. The procedure aims to solve the linear system with a size of \(sN\times sN\). As the matrix is expressed in Kronecker product form and not explicitly formulated, according to Eq. (1), we can also view Eq. (2) as a coupled of s systems each of which is of size \(N\times N\). Although the GMRES(m) takes exactly the same steps for different linear equations, the data layout, communication strategies and performance profilings are totally different when it comes to multiple GPU computing, because the characteristics of the matrix are the most considered factor in performance optimization and generally affect the adoption of implementation strategies. Therefore, in the following discussion, we focus on designing a multi-GPU enabled solver for Eq. (2) by making full ultilization of the features of the matrix in Kronecker product formulation. To evaluate the optimization performance of this solver, we also develop a baseline implementation using the cuSPARSE 12.1 library33. For clarity, we refer to our proposed solver as OKP-Solver (Optimized Kronecker Product Solver) and the cuSPARSE-based implementation as CU-Solver.

The SpMV in Kronecker product form on multiple GPUs

One of the most time consuming steps is SpMV in Kronecker product form (line 3 and line 7) in Algorithm 1. To effectively increase the Compute-to-Access Ratio on the GPU device, we perform the SpMVs by using the property of the Kronecker product:

where vec stands for the vectorization operation that stacks all column vectors of a matrix into a single column, \(\mathcal {\hat{X}} = ( {{\varvec{x}}}^{(1)}, {{\varvec{x}}}^{(2)},.., {{\varvec{x}}}^{(s)} )_{N\times s}\) with \({{\varvec{x}}}^{(i)} = ( x^{(i)}_{11},.., x^{(i)}_{1b},.., x^{(i)}_{N1},.., x^{(i)}_{Nb} )^T\), and \(\mathcal {X} = \text {vec}(\mathcal {\hat{X}})\).

To avoid the frequent formats transform between \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathcal {\hat{X}}\), all column vectors having the size of \(N\times s\) in Algorithm 1, for example \(\mathcal {U}\), \({{\varvec{v}}}_i\), \({{\varvec{w}}}\), are stored and operated in the corresponding matrix formats by spliting the single column into s column vectors. And \(\mathcal {X}\) is never operated except it is required for file output. We then show the distributed data layout for matrices and vectors from Algorithm 1 in Figs. 1 and 2. Considering a multiple GPU environment, each GPU is mapped into a MPI process and communicate with it, and takes a partial job of the total computational workload. For a typical multiphysics problem, \({\mathbf {M}}\) and \({\mathbf {L}}\) are point-block matrices, and partitioned in block rows between processes. The partition of vectors are sticky with that of matrices to ensure that the coupling variables for the same mesh point are not scattered in different devices. In addition, each point-block matrix is divided into main-diagonal and off-diagonal parts to facilitate the communication optimization of SpMV, which is introduced in Section “Communication”.

OKP-Solver

The first step to perform Eq. (3) is to calculate \(\mathcal {\hat{X}} {\mathbf {A}}^T\) locally without communication required. As mentioned above, this benefits from the local storage of \({\mathbf {A}}\). From the view point of global memory accesses on GPUs, performing \(\mathcal {\hat{X}} {\mathbf {A}}^T\) requires \(qs(s+1)\) reads and qs writes when performed as a traditional matrix multiplication, where q is the number of rows in a local device. Besides, shared memory loads and writes, because successive threads need to take a row of data from \(\mathcal {\hat{X}}\) and multiply it with a column from \({\mathbf {A}}^T\) then do vector reduction to get the result. However, the computation can be optimized by writing the resulting matrix as the linear combination of \({{\varvec{x}}}^{(j)}\) as:

where \(a_{ij}\) represents the element at the \(i^{th}\) row and \(j^{th}\) column of \({\mathbf {A}}\). This consideration leads to \((q+s)s\) reads and qs writes. We explain it by Fig. 3 and Algorithm 2 which shows how Eq. (4) are implemented. For the same time step vector \({{\varvec{x}}}^{(j)}\) (a column of \(\hat{\mathcal {X}}\)) is operated in parallel by all successive threads, each of which is responsible for processing one vector element, so that only one transaction needs to be done in the same warp to fetch the data of \({\mathbf {A}}\), with the result denoted as \(\tilde{\mathcal {X}} = ( \tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(1)}, \tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(2)}, \ldots , \tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(s)} )_{N\times s}\).

The calculation process of \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) can be viewed as multiple SpMVs. Like the general SpMV, this also requires communication. It is straightforward to perform \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) by launching s SpMV kernels one by one, but it degrades the performance because the global memory accesses on the same matrix \({\mathbf {M}}\) is not reduced. So does the times of communication. To have both the calculations and communication efficient done on GPUs, we merge the local part of \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}\) in different time steps into one single vector, which is shown in Fig. 4. The reason why this transformation is needed will be discussed in the communication optimization in Section “Communication”.

We show how \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) are computed based on the transformed format of \(\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) in Fig. 5. The rectangular, local matrix \({\mathbf {M}}\) are further divided into the main-diagonal part and off-diagonal part, and separately stored to seek the possible overlap between the calculation and communication. Specifically, the main-diagonal part involves only local operations, and it could be executed while the communication for the remote data required by each local device.

Algorithm 3 lists the implementation kernel for \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) that uses a warp of threads to map the workload of a block row of \({\mathbf {M}}\). This idea is motivated by the point-block matrix and single vector multiplication and our previous work on the ILU factorization for the point-block matrix27,34,35.

The procedure starts with the initialization of the auxiliary vector for the subsequent data reduction in shared memory. A warp of threads is assigned to process a block row of M, and tied to a block identifier g. As a warp can cover \(\left\lfloor 32/b^2 \right\rfloor\) complete blocks, each thread then identifys the local index \(w_l\) within a warp and is mapped to a single element at (r, c) in a block (lines 8–9). Different from a single SpMV operation, multiple SpMVs can increase the data reuse by prefetching the matrix data from the global memory and uses it for s times (line 13–15). Finally, s vector reduction operations are performed through shared memory to obtain the final result of multiple SpMVs and the results are written back to the global memory. Several cycles will be performed by a warp when the warp is unable to cover all blocks at a block row, and different cycles are serial (lines 18–29). Additionally, the reduction logic in Algorithm 3 is general and not restricted to a specific block size. The stride (\(\alpha\)) used in the vector reduction stage, however, varies with the matrix block size b35, and \(\alpha\) should be the value obtain by (32/2b) and then rouding it up to the nearest power of 2.

For ease of understanding, Fig. 6 shows how multiple SpMVs are performed in warps as an example. In this case, the block size is 4, and a warp can handle two complete blocks in a block row at a time. Note that we present \(\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) in multiple segments only for illustration purposes, in fact, it is stored as a merged vector as we have mentioned before. Squares with the same color in \(\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) indicate that the vector data at these positions are being calculated using the same matrix elements. This property allows the matrix data to be loaded once and reused for computing with multiple vectors, thereby reducing redundant memory accesses across multiple SpMVs operations.

CU-Solver

In CU-Solver, the SpMV operation in Kronecker product form is implemented following Algorithm 4. The computation of \(\mathcal {\hat{X}} {\mathbf {A}}^T\) is realized through a two-level loop structure, each consisting of s iterations. Within the innermost loop, the cublasDaxpy function is invoked to perform the required vector accumulation operations (lines 1–8). Afterwards, cudaMemcpy is invoked s times to transfer the data of \(\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) to the host. Then, cusparseDbsrmv is invoked s times to compute the main-diagonal part of \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\). After each cusparseDbsrmv computation, a VecScatter operation handles communication, resulting in a total of s communication calls (lines 10–15). Each communication phase consists of a pair of VecScatterBegin and VecScatterEnd calls, making it non-blocking and allowing partial overlap with subsequent computation. Finally, s cudaMemcpy calls transfer the data back to the device, followed by s cusparseDbsrmv operations to compute the off-diagonal part of \({\mathbf {M}}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\), which are then accumulated to complete \(({\mathbf {A}} \otimes {\mathbf {M}})\mathcal {X}\) (lines 17–20).

Communication

In the processing of computing the \(({\mathbf {A}} \otimes {\mathbf {M}})\mathcal {X}\) implicitly (Eq. (3)), each column vector of \(\mathcal {\hat{X}}\) requires data exchange across GPU devices. This makes the amount of communication and the times of memory copies between hosts and devices increase as the number of columns in \(\mathcal {\hat{X}}\), i.e., s, increases, resulting in increasing overhead. In this subsection, effective considerations are introduced to keep the communication overhead from affecting the overall performance.

Parallel buffering

Since the computation of the \(({\mathbf {A}} \otimes {\mathbf {M}})\mathcal {X}\) can be viewed as the multiple SpMVs, it is straightforward to consider that merging s times of communication into once can reduce the redundant overhead for launching message exchange tasks. To complete this, all the data that needs to be sent to remote devices is required to be extracted from each \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) into the same buffer. Instead of extracting s times one by one, we realize a parallel process to buffer the data simultaneously for all \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}\), which is shown in Algorithm 5. To parallelize the buffer setup, we launch as many threads as the length of the send buffer, allowing each thread to handle one element of the buffer. Since the relative indices of the extracted elements in each \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) are the same, we first compute the length \(\ell\) of a single buffer (line 3). This value is used to determine \(w_s\), which indicates which \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) the current thread is operating on (line 4). Furthermore, \(\ell\) is used to compute \(\varsigma\) and \(o\), which are used to compute a specific index \(\iota\) of the indexed array \({{\varvec{c}}}\), which serves to locate where in \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) the element responsible for the thread originated (lines 5–7). Finally, each thread sets the buffer using \(\iota\), \(w_s\), and the length \(q\) of a single \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) (line 8).

Figure 7 shows how the data is buffered in parallel in the case where device 0 needs to send data to both device 1 and device 2. Each element inside \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) is of size b that corresponds to the block size of \({\mathbf {M}}\). Elements in different colors indicate that they come from different \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\), and elements in the same shape indicate that they are reuired in the same relative position of \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\).

Pre-mapping strategy

As shown in Fig. 7, the layout of the parallel buffering process is in time-step order, and the data in \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\) that will be sent to remote devices are extracted and stored consecutively in the sending buffer. This will cause a problem that the data that needs to be sent to the same device is scattered in the sending buffer, resulting in repeated times of communication with the same device. From the receiver’s perspective, if the sending and receiving buffers are in processor order, the same problem occurs when writing data from the receiving buffer back into \(\tilde{{{\varvec{x}}}}^{(i)}\).

To avoid this problem, we create a sending map and receiving map respectively to arrange the buffers in different orders. The algorithm is listed in Algorithm 6. Note that the mapping arrays only needs to done once and reused to reorder the buffers before the buffers are accessed. Figure 8 shows illustrates the layouts of the sending and receiving buffers before and after the reordering operations in the case where device 0 performs sending and receiving steps. In addition, we use the GPU direct technique in the communication part to realize the direct communication between devices.

Experiments

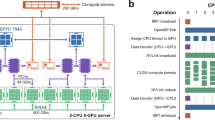

The experiments are conducted on two heterogeneous server platforms. The first platform consists of two computing nodes. Each node is equipped with two Intel(R) Xeon(R) E5-2640 V4 CPUs (with a clock speed of 2.4GHz) and 128 GB of memory. Each CPU has 10 physical cores, giving each node a total of 20 CPU cores. Nodes are interconnected via NVLink within each node, providing an intra-node bandwidth of up to 130 GB/s, while inter-node communication relies on Intel Omni-Path Architecture (OPA) interconnects operating at 100 Gbps. In addition, each node was configured with four Tesla V100 GPUs, each with 16 GB of HBM2 memory. The theoretical peak performance of the GPU is 15.7 TFLOPS for single-precision and 7.8 TFLOPS for double-precision floating-point operations, respectively. The second platform consists of computing nodes equipped with two Kunpeng-920 CPUs running at 3.0 GHz and 220 GB of available memory. In addition, each node is configured with four NVIDIA A100 GPUs, each with 40 GB of HBM2 memory. Each GPU card is by default allocated 32 CPU cores and 55 GB of memory. The nodes are interconnected via \(4\times 100\) Gbps RoCE high-speed links that utilize the RDMA protocol. The theoretical peak performance of the GPU is 19.5 TFLOPS for single-precision and 9.7 TFLOPS for double-precision floating-point operations, respectively.

All the algorithms introducted in above sections are realized based on PETSc (Portable, Extensible Toolkit for Scientific Computation)28. The PETSc version is 3.14.2, and configured with GCC 6.3, OpenMPI 4.0.036 and CUDA 12.137. The most important optimization related compilation flag for the solver is -O3, and the Linux kernel version is 3.10.0-1160.el7.x86_64.

In the numerical experiments, the case is constructed from the unsteady incompressible Stokes problem defined in a three-dimensional computational domain (denoted as \(\Omega \subset \mathbb {R}^3\)). The governing equations are given by

where \(\mathbf{u}\) is the velocity field, p is the pressure, \(\nu\) is the viscosity, \(\mathbf{g}\) is a given source term, and \(\mathbf{u}_0(x)\) is the prescribed initial velocity. The boundary \(\partial \Omega\) is divided into three disjoint parts: inlet \(\Gamma _{in}\), wall \(\Gamma _{wall}\), and outlet \(\Gamma _{out}\). On the inlet and wall boundaries, Dirichlet conditions are imposed:

At the outlet, either a pressure boundary condition or an equivalent stress-free condition is prescribed:

where \(\mathbf{n}\) denotes the unit outward normal vector.The number of mesh points is 151090. Eq. (5) is discretized in space using a stabilized finite element method and solved with a space-time coupled algorithm. The components for Eq. (2), expressed in \(\mathbf{M}\), \(\mathbf{L}\), \(\mathbf{A}\), \(\mathbf{B}\), and \(\tau\), are extracted from the process for performance comparisons and analysis. The main parameters for the matrices and vectors are listed in Table 1. The Kronecker product version of the GMRES, i.e., Algorithm 1, with a restart number of 30 is employed as the main solver for solving the linear system. The absolute and relative tolerance for convergence is set to \(10^{-8}\) and \(10^{-6}\), respectively.

Considering the load balancing problem in communication and computation, we report the execution time as the average values over three experimental runs. For each run, the time of each operation is taken as the maximum across all processes. That is:

where r represents the number of experimental runs and P is the total number of processes uesd.

As a reference, we implemented a CPU-only solver based on PETSc. We employ three timing metrics: \(T_{Kp}\) (time for the SpMV in Kronecker product form), \(T_{other}\) (Time for other operations) and \(T_{all}\) (Overall runtime). To ensure the stability of the tests, we fix the number of iterations at 6000 as the baseline for the subsequent performance analysis. The experimental results of the CPU solver with 1, 2, 4, and 8 cores are reported in Table 2. These experiments were conducted on the V100 platform, where each node is equipped with two Intel(R) Xeon(R) E5-2640 V4 CPUs running at 2.4 GHz and 128 GB of memory. Each CPU has 10 physical cores, providing a total of 20 physical cores per node.

Figure 9 presents the time breakdown of key operations performed on a single GPU, using CU-Solver and OKP-Solver on V100 and A100 platforms. For clarity, the notation used in the GPU experiments is summarized in Table 3, which provides detailed descriptions of all timing components.

On a single GPU, the solver requires no communication during computation, and \(T_{Kx}\) accounts for the majority of the solver’s runtime. Specifically, \(T_{Kx}\) accounts for 76.2% of the total time on V100 and 68.8% on A100 in CU-Solver. In OKP-Solver, \(T_{Kx}\) constitutes 64.5% and 64.2% of the total time on V100 and A100, respectively. Figure 10 shows the time breakdown for each operation of the two solvers on a single node with 2 GPUs.

In Fig. 10, CU-Solver spends most of its runtime on \(T_{dt}\) and \(T_{Kx}\), taking 45.5% and 31.8% on V100, and 53.8% and 22.9% on A100, while \(T_c\) accounts for only 10.2% and 10.6%. In contrast, OKP-Solver is dominated by \(T_{Kx}\) and \(T_{Gn}\), which account for 59.3% and 31.7% on V100, and 56.7% and 30.1% on A100, with \(T_c\) reduced to merely 3.9% and 4.4%. Figure 11 shows the results for both solvers on 4 GPUs within a single node on two platforms. We observe that the proportion of \(T_c\) in CU-Solver increases to 24.2% and 21.4%, while in OKP-Solver, \(T_c\) increases to 13.2% and 13.3%. This is because the matrix data in our case is unevenly distributed, leading to load imbalance. As a result, \(T_c\) increases when using both 4 GPUs and 8 GPUs.

Figure 12 presents the performance of both solvers on 8 GPUs, with the experiment conducted across two nodes. We observe a significant increase in the proportion of \(T_c\) for both solvers on 8 GPUs. In CU-Solver, the proportion increases from 24.2 and 21.4% on 4 GPUs to 55.3 and 28.8% on 8 GPUs. Similarly, in OKP-Solver, it rises from 13.2 and 13.3% to 65.4 and 40.6%. This is because there is a bottleneck in inter-node communication, and the limited network bandwidth will be saturated as the number of GPUs increases. Specifically, when multiple GPUs concurrently exchange data across nodes, contention for shared bandwidth resources occurs, drastically reducing communication efficiency. In addition, A100 platform has higher efficiency in inter-node communication, so the increase in \(T_c\) is less significant compared to V100 platform.

Figures 10a, 11a, and 12a indicate that \(T_{dt}\) constitutes a substantial fraction of the total runtime (\(T_{all}\)) in CU-Solver. Specifically, \(T_{dt}\) accounts for 45.5%, 45.9%, and 28.4% on the V100 platform, and 53.8%, 39.0%, and 23.6% on the A100 platform, corresponding to 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively. This decrease in \(T_{dt}\) proportion on 8 GPUs is attributed to the significant increase in \(T_c\). Importantly, there is more memory copy overhead when solving the Kronecker product form linear system in Eq. (2), as its structure requires much more host-device data transfers compared to general linear systems. Concretely, CU-Solver performs \(s\) rounds of host-device data transfers and host-side VecScatter operations for multiple SpMVs involving \(\mathbf{M}\) or \(\mathbf{L}\), which makes the number of memory copies 2s times that of a general linear system. Consequently, the heavy data copying consumes a large amount of time, making \(T_{dt}\) account for a considerable percentage of \(T_{all}\) in CU-Solver. In contrast, OKP-Solver employs GPU-Direct technology to enable direct device-device communication, effectively avoiding costly host-device memory copies. This optimization reduces \(T_{dt}\) on 2 GPUs from \(11.05\) and \(10.73\,\text {s}\) to \(0.21\) and \(0.18\,\text {s}\). On 4 GPUs, \(T_{dt}\) decreases from \(7.97\) and \(5.48\,\text {s}\) to \(0.22\) and \(0.20\,\text {s}\). On 8 GPUs, it drops from \(8.58\) and \(5.28\,\text {s}\) to \(0.29\) and \(0.30\,\text {s}\). As a result, \(T_{dt}\) accounts for only 3.0% and 3.4% on 2 GPUs, 4.6% and 4.9% on 4 GPUs, and 1.8% and 2.9% on 8 GPUs of the overall time. The low portions of \(T_{dt}\) also show that the proposed parallel buffering (Algorithm 5) and pre-mapping (Algorithm 6) algorithms achieve high efficiency.

Figure 13 shows the speedup of OKP-Solver relative to other CU-Solver components. In particular, for \(T_c\), the combination of parallel buffering (Algorithm 5) and pre-mapping (Algorithm 6) achieves speedups of \(9.18\times\), \(6.82\times\), and \(1.54\times\) on 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively, on V100 platform, and \(8.95\times\), \(5.60\times\), and \(1.62\times\) on A100 platform. The speedup of \(T_c\) on 8 GPUs appears significantly lower compared to that on 2 and 4 GPUs within a single node. The higher communication speedups on 2 GPUs and 4 GPUs within a single node are mainly because OKP-Solver merges s communication rounds into a single round, employs GPU-Direct to bypass the host and avoid redundant operations, and further benefits from the inherently faster intra-node communication bandwidth. The notably lower speedup of \(T_c\) on 8 GPUs arises from the increased inter-node communication overhead, which prolongs communication times for both CU-Solver and OKP-Solver. This effect is largely due to the fundamental difference between intra-node and inter-node communication: while intra-node communication benefits from direct hardware connections and low latency, inter-node communication relies on network protocols and RDMA technology, which differ substantially in bandwidth, latency, and configuration complexity. The situation is further aggravated by load imbalance caused by uneven matrix distribution as the number of processes increases.

A comparison of Figs. 11a and 12a, as well as Figs. 11b and 12b, reveals a counter-intuitive phenomenon: the absolute runtime of \(T_{Gn}\) increases despite a reduced workload for both CU-Solver and OKP-Solver on 8 GPUs. More precisely, \(T_{Gn}\) for CU-Solver rises from \(2.02\) to \(4.29\,\text {s}\) on V100, and from \(2.02\) to \(3.64\,\text {s}\) on A100. For OKP-Solver, \(T_{Gn}\) increases over the same range from \(1.48\) to \(2.80\,\text {s}\) on V100, and from \(1.23\) to \(2.05\,\text {s}\) on A100. The main cause lies in inter-node communication, which increases the communication time within \(T_{Gn}\). \(T_{Gn}\) involves collective operations such as \(MPI\_Allreduce\), which must traverse the network when scaling from a single node to two nodes, rather than remaining within the high-bandwidth intra-node links. This leads to higher latency and lower effective bandwidth, increasing the communication cost and directly affecting the absolute runtime of \(T_{Gn}\). This can be clearly observed from the changes of \(T_{Gn}\) for both solvers when scaling from 4 to 8 GPUs on the two platforms: on A100 platform, which has better inter-node communication performance, the absolute increase in \(T_{Gn}\) is much smaller than that on V100 platform. However Fig. 13 show that the speedup of \(T_{Gn}\) on 8 GPUs reaches \(1.53\times\) on V100 and \(1.77\times\) on A100, surpassing the \(1.37\times\) on V100 and \(1.65\times\) on A100 achieved on 4 GPUs. Unlike \(T_c\), it does not suffer the speedup decrease caused by the same inter-node communication issue. This is because OKP-Solver has good scalability. On 8 GPUs, the good scalability of OKP-Solver on both platforms leads to faster computation, which effectively hides the inter-node communication latency. As a result, compared with 4 GPUs, OKP-Solver achieves a higher speedup for \(T_{Gn}\).

Figure 14 shows the GFLOPS comparisons of the computational part for \(({\mathbf {A}}\otimes {\mathbf {M}}+\tau {\mathbf {B}}\otimes {\mathbf {L}})\mathcal {X}\) between CU-Solver and OKP-Solver when executed on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs on both V100 and A100 platforms. The number of floating-point operations involved in \(({\mathbf {A}}\otimes {\mathbf {M}}+\tau {\mathbf {B}}\otimes {\mathbf {L}})\mathcal {X}\) can be divided into three parts: (1) The computations of \(\hat{\mathcal {X}} \mathbf{A}^T\) and \(\hat{\mathcal {X}} \mathbf{B}^T\), which require \(4qs^2\) floating-point operations; (2) main-diagonal blocks computations of \(\mathbf{M}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) and \(\mathbf{L}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\), which incur a cost of \(4s \cdot nnz_{m} \cdot b^2\) operations, where \(nnz_{m}\) is the number of nonzeros in the main-diagonal blocks; and (3) off-diagonal blocks computations of \(\mathbf{M}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\) and \(\tau \mathbf{L}\tilde{\mathcal {X}}\), which contribute \(4s \cdot nnz_{o} \cdot b^2 + 3qs\) operations, where \(nnz_{o}\) denotes the number of nonzeros in the off-diagonal blocks. For this case, performing \(({\mathbf {A}}\otimes {\mathbf {M}}+\tau {\mathbf {B}}\otimes {\mathbf {L}})\mathcal {X}\) once requires 293,200,460 floating-point operations. It can be observed from Fig. 14 that the GFLOPS performance has increased significantly through the proposed optimization strategy which improves CMAR and makes better use of the GPUs. On V100 platform, OKP-Solver achieves 83.58%, 86.68%, 84.83%, and 91.11% GFLOPS improvements over CU-Solver on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively, while on A100 platform the improvements are 45.41%, 50.03%, 64.55%, and 65.68%.

We conducted a roofline model analysis of the OKP-Solver kernel, \((\mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{M} + \tau \mathbf{B}\otimes \mathbf{L})\mathcal {X}\), on both platforms. Roofline model is a performance analysis tool that relates a kernel’s achievable floating-point performance to its arithmetic intensity (i.e., the number of floating-point operations per byte of memory accessed) and the hardware limits of the processor, such as peak FLOPS and memory bandwidth38. Figure 15 illustrates the roofline model of the OKP-Solver kernel when performing the computation \((\mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{M} + \tau \mathbf{B}\otimes \mathbf{L})\mathcal {X}\) on two platforms. Experiments were performed on a single GPU to measure the arithmetic intensity and the achieved double-precision performance. The kernel achieves an arithmetic intensity of approximately 0.23 FLOP/Byte, given by

where AI is arithmetic intensity, F is the total number of floating-point operations and B is the total number of bytes transferred between memory and the GPU. For reference, the machine balance point, calculated using the double-precision peak performance, is 8.7 FLOP/Byte for V100 and 5.0 FLOP/Byte for A100.

We observe from Fig. 15 that our kernel is memory bandwidth-bound on both platforms. This is due to the type of large-scale sparse problem we are studying, which typically suffers from memory bandwidth limitations on GPUs39,40.

Figure 16 presents the residual convergence curves of CU-Solver and OKP-Solver on V100 and A100 platforms. In this case, both solvers exhibit almost identical convergence behavior on two platforms, reaching convergence after 117 iterations.

Conclusion

In this paper, parallel, multi-GPU enabled algorithms for efficiently solving linear systems derived from domain decomposition based space-time parallel methods are proposed and optimized. The OKP-Solver accelerates the GMRES method in Kronecker product form in both computation and communication. Compared to a general cuSPARSE based implementation, i.e., CU-Solver, \(T_{Kx}\) achieves speedups of \(2.00\times\), \(1.87\times\), \(1.85\times\), and \(1.91\times\) on 1, 2, 4 and 8 V100 GPUs, and \(1.43\times\), \(1.50\times\), \(1.64\times\), and \(1.64\times\) on 1, 2, 4 and 8 A100 GPUs, respectively. Furthermore, by employing parallel buffering and pre-mapping strategies combined with GPU-Direct, the communication time \(T_c\) is accelerated by \(9.18\times\), \(6.82\times\), and \(1.54\times\) on V100, and \(8.95\times\), \(5.60\times\), and \(1.62\times\) on A100, for 2, 4, and 8 GPUs, respectively. The experiments show that the overall runtime \(T_{all}\) of OKP-Solver achieves speedups of \(1.70\times\), \(3.48\times\), \(3.70\times\), and \(1.82\times\) on 1, 2, 4, and 8 GPUs of V100 platform, and \(1.33\times\) \(3.70\times\), \(3.48\times\), and \(2.28\times\) on A100 platform, respectively. This solver is expected to be used in multiphysics applications with space-time coupling.

Data Availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Tinney, W. F. & Walker, J. W. Direct solutions of sparse network equations by optimally ordered triangular factorization. Proc. IEEE 55(11), 1801–1809 (1967).

Saad, Y. & Schultz, M. H. Gmres: A generalized minimal residual algorithm for solving nonsymmetric linear systems. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 7(3), 856–869 (1986).

Lions, J.-L. Résolution d’edp par un schéma en temps «pararéel» a “parareal’’ in time discretization of pde’s. Academie des Sciences Paris Comptes Rendus Serie Sciences Mathematiques 332(7), 661–668 (2001).

Gander, M. J. & Vandewalle, S. Analysis of the parareal time-parallel time-integration method. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 29(2), 556–578 (2007).

Minion, M. L., Speck, R., Bolten, M., Emmett, M. & Ruprecht, D. Interweaving PFASST and parallel multigrid. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 37(5), S244–S263 (2015).

Horton, G. & Vandewalle, S. A space-time multigrid method for parabolic partial differential equations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 16(4), 848–864 (1995).

Gander, M. J. & Neumuller, M. Analysis of a new space-time parallel multigrid algorithm for parabolic problems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 38(4), A2173–A2208 (2016).

Margenberg, Nils & Munch, Peter. A space-time multigrid method for space-time finite element discretizations of parabolic and hyperbolic pdes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04372, (2024).

Güttel, Stefan. A parallel overlapping time-domain decomposition method for odes. In Domain decomposition methods in science and engineering XX pages 459–466. Springer, (2013).

Lelarasmee, E., Ruehli, A. E. & Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A. L. The waveform relaxation method for time-domain analysis of large scale integrated circuits. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Tntegr. Circuits Syst. 1(3), 131–145 (2004).

Tran, M.-B. Parallel schwarz waveform relaxation algorithm for ANN-dimensional semilinear heat equation. ESAIM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 48(3), 795–813 (2014).

Bennequin, D., Gander, M. & Halpern, L. A homographic best approximation problem with application to optimized schwarz waveform relaxation. Math. Comput. 78(265), 185–223 (2009).

Li, S., Shao, X. & Cai, X.-C. Highly parallel space-time domain decomposition methods for parabolic problems. CCF Trans. High Perform. Comput. 1(1), 25–34 (2019).

Axelsson, O., Dravins, I. & Neytcheva, M. Stage-parallel preconditioners for implicit Runge–Kutta methods of arbitrarily high order, linear problems. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 31(1), e2532 (2024).

Kirby, R. C. On the convergence of monolithic multigrid for implicit Runge-Kutta time stepping of finite element problems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 46(5), S22–S45 (2024).

Tang, Yu-Hang., Selvitopi, Oguz, Popovici, Doru Thom & Buluç, A. A high-throughput solver for marginalized graph kernels on gpu. In 2020 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), pages 728–738. IEEE (2020).

Tan, Yu., Cai, Yunfeng & Li, Ping. Efficient compact bilinear pooling via kronecker product. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3170–3178 (2022).

Lin, J. A., Ament, S., Balandat, M. & Bakshy, E. Scaling gaussian processes for learning curve prediction via latent kronecker structure. In NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on Bayesian Decision-making and Uncertainty (2024).

Gonon, Antoine, Zheng, Léon., Carrivain, Pascal & TUNG QUOC L. E. Fast inference with kronecker-sparse matrices. In Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning (2025).

Cui, C., Grosse-Bley, P., Kanschat, G. & Strzodka, R. An implementation of tensor product patch smoothers on GPUs. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 47(2), B280–B307 (2025).

Crews, D. W. Analysis of tensor-product discontinous galerkin operators for vlasov-poisson simulations and gpu implementation on python. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.13532, (2022).

Jangda, A & Yadav, M. Fast kronecker matrix-matrix multiplication on gpus. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGPLAN Annual Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming, pages 390–403, (2024).

Jhurani, C. Batched kronecker product for 2-d matrices and 3-d arrays on nvidia gpus. arXiv preprint arXiv:1304.7054, (2013).

Keyes, D. E. et al. Multiphysics simulations: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 27(1), 4–83 (2013).

Kashi, Aditya & Nadarajah, Sivakumaran. Fine-grain parallel smoothing by asynchronous iterations and incomplete sparse approximate inverses for computational fluid dynamics. In AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, page 0806 (2020).

Kashi, A. & Nadarajah, S. An asynchronous incomplete block LU preconditioner for computational fluid dynamics on unstructured grids. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 43(1), C1–C30 (2021).

Ma, W. & Cai, X.-C. Point-block incomplete LU preconditioning with asynchronous iterations on GPU for multiphysics problems. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 35(2), 121–135 (2021).

Balay, S. et al. PETSc Web page. https://petsc.org/, (2025).

NVIDIA cuSPARSE Library. https://developer.nvidia.com/cusparse, (2025).

The Trilinos Project Team. The Trilinos Project Website. https://trilinos.github.io, (2020).

Intel Math Kernel Library Documentation. https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/resources-documentation/developer.html, (2025).

hypre: High performance preconditioners. https://llnl.gov/casc/hypre, https://github.com/hypre-space/hypre.

NVIDIA cuSPARSE Library, release: 12.1. https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/archive/12.1.0/cusparse, (2023).

Abdelfattah, A., Ltaief, H., Keyes, D. & Dongarra, J. Performance optimization of sparse matrix-vector multiplication for multi-component PDE-based applications using GPUs. Concurr. Comput. Practice Exp. 28(12), 3447–3465 (2016).

Eberhardt, Ryan & Hoemmen, Mark. Optimization of block sparse matrix-vector multiplication on shared-memory parallel architectures. In 2016 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium Workshops (IPDPSW), pages 663–672. IEEE, (2016).

MPI: A message-passing interface standard version 4.0. https://www.mpi-forum.org/docs/mpi-4.0/mpi40-report.pdf, (2021).

NVIDIA CUDA, release: 12.1. https://developer.nvidia.com/cuda-toolkit, (2023).

Williams, S., Waterman, A. & Patterson, D. Roofline: An insightful visual performance model for multicore architectures. Commun. ACM 52(4), 65–76 (2009).

Shi, Shaohuai, Wang, Qiang & Chu, Xiaowen. Efficient sparse-dense matrix-matrix multiplication on gpus using the customized sparse storage format. In 2020 IEEE 26th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), pages 19–26. IEEE, (2020).

Zhixiang, Gu., Moreira, Jose, Edelsohn, David & Azad, Ariful. Bandwidth optimized parallel algorithms for sparse matrix-matrix multiplication using propagation blocking. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM Symposium on Parallelism in Algorithms and Architectures, pages 293–303 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Innovation Team Support Plan of Science and Technology of Henan Province (252102210219) and the Nanhu Scholar Program of XYNU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M. was responsible for the methodology, supervision, and overall project guidance. S.Z. developed the code, conducted the experiments, drafted the manuscript, and created the figures. X.L. was responsible for organizing and processing the data. W.Y. provided the experimental platform and related resources. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, W., Zhao, S., Le, X. et al. A multi-GPU enabled solver in Kronecker product form for multiphysics problems. Sci Rep 15, 43529 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27400-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27400-3