Abstract

Crustacean shell waste, a mostly untapped marine byproduct, presents considerable environmental risks while also offering a rich but underutilized source of biopolymers. Although chitosan nanoparticles (ChNPs) have received attention for their bioactivity and biocompatibility, most research focuses on commercial chitosan, ignoring local waste valorization, complete nanoparticle characterisation, and cross-disciplinary applications. To bridge these gaps, the current work presents an integrated, sustainable methodology to convert Penaeus monodon shell waste into bio-functional chitosan nanoparticles by green ionic gelation. Physicochemical investigations (FESEM, TEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA, and DLS) revealed crystallinity, thermal stability, and consistent nanoscale shape of the molecule. The ChNPs showed better antibacterial efficiency against fish pathogens and antioxidant activity (DPPH and H2O2). Additionally, cytotoxicity screening on NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells supported their high biocompatibility. Notably, a new chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) hydrogel composite was developed and evaluated as a natural covering for post-harvest fruit preservation. While these findings are promising, more focus on antimicrobial studies, multi-cell line and in vivo biosafety validation, optimization of hydrogel formulation and large-scale trials should be done in future. This work establishes a circular economy model linking waste management, nanotechnology, and biological efficacy on a single platform, bridging research gaps and opening new pathways for sustainable applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the recent introduction of aquaculture, 6–8 million tonnes of crustacean waste are produced globally each year1. Shrimp, being a significant portion of aquaculture’s output, its processing produces chitinous waste, which is resistant to biological degradation; it might be harmful if disposed of unreasonably, as well as the waste of biomaterials. Consequently, it is an excellent chance to use the waste of shrimp shells to make value-added products like chitin, chitosan and their derivatives2. Chitosan is a natural biopolymer derived from chitin through a chemical process that removes acetyl groups3 and exhibits distinctive characteristics such as biocompatibility, minimal toxicity, and biodegradability. These remarkable properties have led to its extensive utilization in various industries, agriculture and the food sector4,5. Furthermore, chitosan has found applications in diverse fields, such as water treatment, where it acts as a flocculating agent and in cosmetics, where it serves as a dehydrating agent. Its uses extend to food preservation, and additives, in the pharmaceutical industry, chitosan is employed as a drug delivery system and hydrogel film, while its antimicrobial properties make it valuable in combating microbial activity6. Thus, their effective utilization presents a compelling opportunity for promoting sustainability and embracing the waste-to-wealth paradigm, an approach that converts environmental liabilities into valuable resources through green technology and circular bioeconomy principles.

Chitosan nanoparticles (ChNPs), representing the characteristics of natural or chemically altered chitosan polymers, can greatly expand the functionality of chitosan due to their higher surface-to-volume ratio, improved stability, and tailored physicochemical characteristics. Chitosan-derived nanoparticles have been extensively researched as a biocompatible substitute for metal nanoparticles in biological uses, including pharmaceutical delivery. There are several approaches to synthesizing ChNPs, namely electrospray, emulsification, solvent diffusion, micro-emulsion techniques, and ionic gelation7. The current study’s adoption of the ionic gelation method was done using an improved protocol that makes use of STPP (Sodium tripolyphosphate) as an anionic crosslinker. The NH3+ groups of the acidified chitosan form cross-links with the STPP anions, resulting in the three-dimensional arrangements that make up the ChNPs8,9. Ionic gelation is uncomplicated, ecological, less hazardous, gentle, flexible, practical, and controlled.

Despite the availability of various synthesis protocols, most previous studies have focused on commercial-grade chitosan sources, overlooking the valorization of indigenous and locally available shrimp shell waste, particularly from species like Penaeus monodon. This has resulted in a research gap regarding region-specific biopolymer characterization, optimization of nanoparticle formulation, and the full spectrum of biological activities, including antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic evaluations.

ChNPs have been synthesised from various crustacean sources, mainly Litopenaeus vannamei and crab shells and are commonly utilised in biomedical, pharmacological and aquaculture practices. For example, Rai10 made alginate-chitosan hydrogel beads with L. vannamei head protein hydrolysate. They were more concerned with the distribution and stability during in vitro digestion. Eissa11 documented chitosan nanoparticles sources from L. vannamei for film and aquafeed applications. Concurrently, research involving Portunus spp. shells have demonstrated antimicrobial and scaffold properties12,13,14. Previous research restricted P. monodon chitosan to only antibacterial and material characterization15,16. In contrast, our study uses discarded shell waste of P. monodon, an underutilized yet abundant shrimp resource in Asian aquaculture, to synthesize ChNPs and study its antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxicity screening and (CMC)-chitosan hydrogel composite for post-harvest preservation.

Moreover, comprehensive studies integrating extraction, nanoparticle formulation, structural and functional analysis, and biological application in a single continuum are scarce. There is also limited literature addressing the formulation of biopolymer-based hydrogel composites for real-world applications like food preservation, especially in topical contexts where post-harvest losses are significant.

In consideration of the significance, an attempt has been made to extract chitin and chitosan using a chemical approach from local shrimp shell wastes, following its nano-preparation with a detailed exploration of their physicochemical, functional, antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties.

Materials and methods

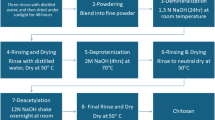

Preparation of chitin and chitosan

The raw shrimp shell waste materials were pre-treated to remove any dirt or debris under running tap water and were then processed in three main steps to extract chitosan, including demineralization with (1:15 w/v) of 1N HCl for 2 h at 50 °C, deproteinization with 15% NaOH in a ratio of (1:15) for 3 h at 65 °C, and deacetylation with 65% NaOH solution for 1 h at 100 °C under continuous stirring on a magnetic stirrer (REMI, 1-MLH) at 1000 rpm to obtain chitosan following oven drying. After each step, the residue was filtered by repeated washing with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved.

Synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

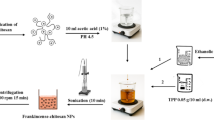

The harvested shrimp chitosan and commercial chitosan with 1% acetic acid (5 mg/ml) were mixed properly using a magnetic stirrer (REMI, 1-MLH), keeping the pH in the range of 3.0–6.517. The above-prepared chitosan solution was then diluted with the STPP solution (3:1) and continuously stirred for 30 min to obtain uniform-sized ChNPs (Fig. 1).

Preparation of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and chitosan (CH) composite hydrogel (CMC-CH)

Three distinct concentrations of hydrogel were formulated by combining CMC and CH solutions, denoted as T1(1:1), T2(1:0.5) and T3(0.5: 1). The solutions with varying ratios were thoroughly mixed under continuous stirring for 30 min at a speed of 500 rpm.

Characterization

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) imaging of chitin and chitosan was conducted at magnifications of 500 X to 5.0 KX (Sigma 300 from Carl Zeiss, Germany), producing images characterized by significantly enhanced clarity, minimal electrostatic distortion, and an impressive spatial resolution reaching as low as 1.5 nm, a notable improvement over traditional Scanning electron microscope (SEM)18. Infrared spectral analysis was conducted using a Frontier Spectrometer (FTIR-Spectro, PerkinElmer, Spectrum Two Version 10.4.3) equipped with a UATR Two connection. The spectra were obtained at a resolution of 4 cm-1, covering the wavelength range from 450 to 4000 cm-119. Using FTIR spectroscopy, the DD of chitosan was computed using the band at A1655/A3450 as the formula suggested by Domszy and Roberts20, DD = 100 − [(A1655 /A3450) X 100 / 1.33]. To assess the crystallinity of chitosan, an X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern was obtained21. Using a Japanese Shimadzu DTG-60 device, Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed. The sample was heated at a rate of 10 °C per minute between 30 and 600 °C in a nitrogen environment that flowed at 30 ml min-122. To measure the colour of the chitin and chitosan samples, a Hunter Lab EasyMatch QC instrument was equipped with a dual-beam xenon flash lamp. Colour assessment was conducted using a three-dimensional scale known as Lab*. The viscosity of the homogenous chitosan solution was determined at room temperature with the help of an Ostwald viscometer23, and the molecular weight was determined with the method as defined prior24,25. The Mark-Houwink equation was used to compute the average molecular weight, which was found to be η = KMa. Here, [η] represents the intrinsic viscosity, M denotes the average molecular weight of the solution, and the Mark-Houwink constants for a particular polymer are K (= 4.74 dL gm-1) and “a” (= 0.72)23. The Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of chitosan nanoparticles were taken (TEM-2100Plus, Camera used: GATAN RIO-9) to scrutinize the size, form, and morphology of the prepared nanoparticles. Using Dynamic light scattering (DLS), the chitosan nanoparticles’ particle size, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI) were ascertained.

In vitro antimicrobial activity

Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activity of nano chitosan of different concentrations (5 mg ml-1, 1 mg ml-1 and 0.5 mg ml-1) was screened against selected fish pathogens, Aeromonas hydrophila (ATCC-7966) and Escherichia coli (ATCC-25922) using the disc diffusion method in a triplicate manner. Prepared Muller Hinton Agar (Hi-media) plates, and swabbing with specific concentrations of bacteria was used for screening. Sterile paper discs of 6 mm in diameter (Hi-media) were soaked with different concentration solutions. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured as the average of three experiments. Two reference commercial antibiotic discs, namely tetracycline (T) (25 mcg) and streptomycin (S) (10 mcg), were utilized for comparing the antibacterial activity of chitosan and nano chitosan.

Antifungal activity

To evaluate radial growth, sterile ChNPs solution was incorporated into Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose (YPED) at 5 mg ml-1, 1 mg ml-1 and 0.5 mg ml-1. The antifungal efficacy of nanoparticles has been examined in triplicate against two important fish fungal pathogens, Aphanomyces invadens and Saprolegnia parasitica, in the Aquatic Environmental Biotechnology and Nanotechnology (AEBN) division, ICAR-CIFRI, Barrackpore, India. YPED medium was produced and individually poured onto Petri plates containing different quantities of sterile ChNPs. Mycelial agar plugs of uniform size (diameter: 7.0 mm) were extracted from the actively developing peripheral end of a 7-day-old culture of the test pathogens and introduced at the centre of plates supplemented with varying amounts of ChNPs. All Petri dishes were cultured at 28 °C for 7 days, and observations of radial mycelial expansion were recorded when the control Petri dish exhibited complete growth. A. invadens plates were incubated for five days due to their rapid development. Each treatment included three replications26.

DPPH scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity was evaluated using the DPPH assay, following a slightly modified version of the method described by Blois27. All measurements were carried out in triplicate. Chitosan and DPPH-methanol solution (1 ml, 0.1 mM) were thoroughly combined. By using a spectrophotometer, both before and following a 60-min incubation period at 37 °C, the absorbance at 517 nm was determined. As a positive control, ascorbic acid (ASA) was employed.

The following formula was used to express DPPH scavenging as a percentage:

H2O2 scavenging assay

Mukhopadhyay’s28 method was used to examine the scavenging potential. Chitosan was mixed with hydrogen peroxide (10 mM), and the combination was then left to sit at 25 °C for 30 min. Then, 0.25 ml of ammonium ferrous sulphate (1 mM) and 1.5 ml of 1,10-phenanthroline (1 mM) were applied. The resulting solution turned crimson red after half an hour, and the absorbance at 510 nm was determined with a UV–visible spectrophotometer in triplicate. ASA served as a positive control.

The formula used to calculate the scavenging effectiveness as a percentage was (A test/A blank) × 100, where A test is the absorbance of the test sample that contained H2O2, and A blank is the absorbance of the blank sample that contained 1,10-phenanthroline and ammonium ferrous sulfate.

Cell viability

Mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells were seeded at 3.5 X 103/ well in 96-well TC plates in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) along with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, samples in triplicate at different concentrations (100 µg ml-1, 200 µg ml-1, 300 µg ml-1 and 400 µg ml-1) were added to the respective wells in duplicate. Following 72 h of incubation, WST-1 was added at 10ul/ well and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm and 620 nm. The absorbance at 620 nm was subtracted from 450 nm, and the graph was plotted. In each of the exposure groups, the reduction in cell viability was estimated.

Coating of grapes with CMC-CH hydrogel

Grapes were acquired from the fruit marketplace and surface-disinfected by dipping in 0.1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 2 min, washed and dried for 2 h at room temperature. After drying, the grapes were coated with CMC-CH composite hydrogel of various concentrations [T1 (1:1), T2 (1:0.5), and T3 (0.5:1)]. The qualities of coated as well as control grapes were observed for 14 days by measuring the weight loss percentage, pH, and decay observations.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s post hoc test to determine significant differences among the mean values at a significance level of P < 0.05. Each sampling and analysis were conducted in three replicates and carried out using SPSS version 22. Graphical representations of the results were generated in Microsoft Excel, while the cytotoxicity and FTIR spectra were plotted using Origin software.

Results and discussion

FESEM was used to examine the morphology of chitin and chitosan generated from shrimp shells, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The virgin shrimp shell developed a lamellar-like structure with ovoidal apertures that were smooth and sharper as it was demineralized and deproteinized. Rod-shaped formations started to develop when this chitin was deacetylated into chitosan, some of which were fragmented and small in size, indicating incomplete dissolution of chitin. Similar apertures and fibres on the examined chitin and chitosan were found to support earlier discoveries in insects and crustaceans in the study25,29.

FTIR can recognize and characterize the majority of organic substances by identifying the functional groups, side chains, and cross-links in the organic molecular groups and compounds30. The FTIR analysis (Fig. 3) revealed a remarkable similarity in the chemical configuration and bonding trend between shrimp chitosan, commercial chitosan and respective nano chitosan. The FTIR results of chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles showed an absorption pattern at wavenumbers between 3500 and 2400 cm-1, which indicated a stretching bond of the OH functional group, hydrogen intramolecular bonds and NH2 bond with the OH stretching vibration. The absorption at 1475–1600 cm-1 is correlated to the stretching vibration C = C. The absorption peak 1000–1300 cm-1 signifies the C–N stretching set related to the amine group and stretching vibration of glucosamine, while the absorption peak at 800–900 cm-1 corresponds to ring stretching for ß-1–4 glycosidic linkage, all of which is indicative of the saccharide structure of chitosan31,32. The FTIR graph verified the presence of free amine, hydroxyl, and ether groups in the chitosan nanoparticle spectrum.

Because of its advantages, including its reasonable speed and the fact that it doesn’t necessitate dissolving the chitosan sample in any aqueous solution, the FTIR spectroscopic technique is frequently used to determine chitosan DD values30. The degree of acetylation is one of the most important parameters impacting chitosan quality, and it increases as chitosan purity does as well. The degree of deacetylation is thought to be a major factor in evaluating the biological activity, polymeric and physical characteristics, and therapeutic applications of chitosan33. In the current study, the DD of shrimp chitosan and commercial chitosan are 74.46% and 76.01%, respectively. According to No and Meyers34, the DD of chitosan ranges from 56 to 99%, with an average of 80%. In addition to the source and purification method, the type of analytical techniques used, such as the method of sample preparation and the use of instruments, has a substantial impact on the results35. Moreover, the DD plays a crucial role in defining the viscosity, molecular weight, solubility, and chemical reactivity of chitosan.

The XRD diffractogram of the chitosan samples is shown in Fig. 4A. Chitosan obtained from shrimp revealed a total of five distinct prominent peaks at 45.73°, 36.84°, 35.02°, 31.85° and 30.74°, along with several weaker peaks. Likewise, the XRD analysis of commercial chitosan displayed a strong peak measured at 19.82°, while the remaining peaks were comparatively weaker. Notably, the chitosan isolated from shrimp shell waste in the present study exhibited a revealingly high crystallinity in comparison to commercial shrimp chitosan in terms of their XRD patterns. Strong intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonding can be formed by a multitude of hydroxyl and amino groups, which contribute to the high crystallinity of chitosan. Additionally, there is some regularity in the structure of chitosan molecules. As a result, chitosan molecules could form crystalline regions very easily.

The thermogravimetric curves generated in Fig. 4B represent a valuable way to examine the weight loss properties of a sample, evaluate its thermal stability, analyse reaction kinetics, and clarify weight loss trends. According to Woranuch and Yoksan36, thermal stability is the ability of a material to adapt to changes in temperature that occur in both environments with regulated temperatures and inert gas flows. The shrimp chitosan and commercial chitosan showed a weight loss of 12% and 15%, respectively, during the first stage of weight loss, which occurred between 30 and 250 °C, where the water molecules begin to evaporate, which appears to be the cause of the initial stage of decomposition. Next comes a second period of transitional weight loss between 250 and 400 °C, which in shrimp and commercial chitosan, respectively, accounted for 28% and 47% of the weight loss. As previously observed32,37, the second stage of degradation involves the breakdown of the acetylated and deacetylated units of chitin as well as the dehydration of saccharide rings and polymerization. The weight loss for shrimp chitosan and commercial chitosan in the final (3 stages) between 400 and 800 °C was reported to be 19% and 35%, respectively. Notably, commercial chitosan showed significant thermal deterioration as compared to shrimp chitosan, suggesting that commercial chitosan is not as thermally stable as shrimp chitosan in high-temperature environments38.

Colour indices of shrimp chitin and chitosan, as well as commercial chitosan, are represented in Table 1. In the current study, the shrimp chitin and chitosan have low L* and a* value as compared to commercial chitosan, indicating a more white or pale yellow colouration than commercial. However, the values are very close to commercial chitosan, representing low brightness and more colour intensities in shrimp extracts25. Based on the value of the Ostwald viscometer, the viscosity of the sample was observed to be low with a poise value. Consequently, the molecular weight of the shrimp chitosan that was obtained was 97.52 KDa. To verify the method’s effectiveness, medium molecular weight commercial chitosan was also run in parallel. The latter had a molecular weight of 336.256 KDa, indicating that, in comparison to high molecular weight chitosan, the extracted shrimp chitosan with a lower molecular weight has better qualities like biodegradability, biocompatibility, bioactivity, lower toxicity, and antibacterial activity39. Furthermore, compared to high molecular-weight chitosan, low molecular-weight chitosan has greater solubility and reduced viscosity, enabling a larger range of medicinal applications40,41.

Confirmed by DLS measurement and transmission microscopy observation (Fig. 5B), the commercial chitosan nanoparticles with a size range of 30–150 nm were obtained and well dispersed in the solution. The polydispersity index (PDI) was 14.4%, hydrodynamic diameter 34.05 ± 7.8 nm, and the particle size of shrimp chitosan nanoparticles was measured as 69.3 ± 16.7 nm by DLS (Fig. 6B), which is consistent with the TEM observation with no severe agglomeration of the particles. A magnified TEM image (Figs. 5A and 6A) illustrates that the nanoparticles had a spherical homogeneous structure and were consistently dispersed42,43. All the observations are in close comparison with the commercial chitosan nanoparticles.

In vitro, cytotoxicity methods play a crucial role in evaluating the biocompatibility of new formulations. After examining the impact of these formulations on cell growth rates in culture, clearing toxicity profiles offers both time and cost benefits. This study utilized NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblast cells due to their presence in the body’s matrix and connective tissue, making them a common choice for assessing the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of various formulations44.

Various parameters, including chitosan concentration, molecular weight, and DD may influence the cytotoxic activity of ChNPs. Cytotoxicity testing was conducted on commercial chitosan extracted from shrimp and their respective nano chitosan in 3T3 cells. Across exposure concentrations ranging from 100 to 400 µg/ml, neither chitosan nor chitosan nanoparticles exhibited any cytotoxic effects (Fig. 7), which strengthens the proposition that shrimp chitosan nanoparticles are harmless. The concentrations employed in our cytotoxicity study were chosen based on previous literature studies45, and the results are expressed as cell viability percentages. Both nanoparticle types exhibited high cell viability across all tested concentrations with minimal deviation from the control. Shrimp nano chitosan maintained cell viability consistently around 95–100% even at the highest concentration (400 µg/ml), and commercial nano chitosan also displayed high viability with no significant decrease with increasing concentration. The findings show that they are safe in vitro, setting the groundwork for biological and pharmacological investigations.

The authors proposed that particle size exerted a greater impact on cytotoxicity in Caco-2 cells compared to positive surface charge, attributed to the enhanced cellular uptake of smaller particles over larger ones46 This finding aligns with the study by Zheng47, which demonstrated that chitosan nanoparticles, despite accumulating intracellularly to a greater extent than chitosan molecules, maintained good viability of Caco-2 cells. The MTT-based cytotoxic analysis also demonstrated the non-toxic characteristics of CS-NPs/NAR towards normal 3T3 fibroblast cells48. The toxicity of chitosan extracted from tiger prawn shell waste on BHK-21 cell culture revealed that chitosan concentrations from 0.25 to 1% did not induce toxicity in BHK-21 cells. All novel shrimp chitosan-containing nanoparticles still need to undergo a comprehensive cytotoxicity test on normal and cancer cell lines to determine their suitability for use in clinical, tissue engineering, drug delivery applications and other biomedical research49,50.

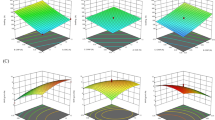

Research on the protective effects of chitosan and its derivatives against free radicals, including hydroxyl, superoxide, peroxide, and DPPH, has been conducted extensively over the years. Antioxidant qualities can be attributed to deacetylated low molecular-weight chitosan, which is in particular51. The antioxidant potential of chitosan and its nano form was evaluated using DPPH and H2O2 assay, demonstrating the dose-dependent characteristics as illustrated in Fig. 8. The current investigation shows that as concentrations rise, so does the scavenging rate of chitosan and ChNPs, with 200 µg showing the maximum level of inhibition. One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test revealed significant differences among treatments and concentrations (P < 0.05).

Fruits can become infected with bacteria while being transported and stored, which can cause them to lose weight, lose quality, or even experience physiological decline. Table grapes are a valuable dessert fruit with significant economic value. However, once harvested, they lose quality quickly, as evidenced by rapid weight loss, colour changes, accelerated ripening and softening, rachis browning, and a high incidence of berry decay52. As a result, their shelf life is reduced. Manufacturing edible, naturally biodegradable coverings to preserve fruit quality after harvest is gaining popularity as an alternative to commercially available synthetic waxes. We investigated the ability to preserve table grape postharvest quality using a recently developed edible bilayer covering based on polysaccharides, including chitosan and CMC. The coating’s ability to preserve morphological and microstructural characteristics was shown by the results in Table 2 and Fig. 9, suggesting that it may be applied to table grapes to increase their shelf life and preserve their quality53,54. The observed reductions in weight loss and decay in coated grapes are consistent with recent findings that composite edible films can better preserve fruit quality than single polymer coatings. Chang55 and Chen56 demonstrated that modified starch-chitosan and CMC-CS films, respectively, delay deterioration in grapes and strawberries. Unlike these studies, which relied on starch or bulk chitosan, our work enhances both antimicrobial efficacy and moisture barrier properties. However, these results are preliminary evidence of potential usefulness in post-harvest preservation and important aspects such as consumer acceptability, sensory quality, scalability for commercial fruit processing and cost effectiveness were not evaluated in this study.

As shown in Table 2, coating grapes with CMC-chitosan hydrogels significantly reduced weight loss and delayed changes in pH compared to the control (P < 0.05).

Chitosan is a versatile material with proven antimicrobial activity. The inhibition of bacterial growth could be that the microorganisms’ anionic groups bonding to the cationic amino groups of chitosan. Furthermore, tiny chitosan molecules may directly bind to DNA and prevent DNA transcription and mRNA translation once they have penetrated bacterial cell walls. The study results indicated (Table 3) that the maximum zone of inhibition observed in shrimp nano chitosan (SN1), and commercial nano chitosan (CMN1 & CMN2) was to be (12 mm and 17 mm) respectively. These discoveries offer a fresh strategy to improve antibacterial activity against A. hydrophila and E. coli. However, a variety of factors affect its activity, such as the bacterial target and growth, in addition to its concentration, pH, zeta potential, molecular weight, and acetylation level57. The primary cause of chitosan’s antimicrobial activities is thought to be interference with cell membrane permeability; as a result, internal components will be externalized, resulting in cellular death. Similar to the way pH affects chitosan’s solubility, it also has an impact on the electrical charges that each chitosan molecule carries. Chitosan molecules may bond together by electrical interactions due to this characteristic58. The statistical analysis confirmed that higher concentrations produced significantly larger inhibition zones.

The antifungal efficacy of various ChNPs was assessed against fish pathogenic fungus, revealing that the nanoparticles suppressed the radial proliferation of pathogens at varying concentrations compared to the control treatment (Fig. 10). Nevertheless, there is little study regarding the antifungal mechanisms of the A. invadens and S. parasitica strains on chitosan nanoparticles, the results indicate that an increase in concentration correlates with a greater growth inhibition rate compared to the control and STPP. The radial growth of S. parasitica was entirely suppressed at 5 mg ml-1 and 1 mg ml-1, indicating a wide-ranging applicability for the control of fish diseases.

The inhibitory zones found against A. hydrophila and E. coli, in addition to the suppression of A. invadans and S. parasitica, indicate that ChNPs exhibit significant in vitro antibacterial activity. However, the current findings must be regarded as preliminary, necessitating more validation prior to the establishment of practical applications in aquaculture disease management.

When compared with earlier work, our approach differs in both the raw and application endpoints. Previous studies emphasized material characterization, drug delivery, scaffold preparation or aquaculture nutrients, whereas the present study demonstrates a complete picture of how P. monodon shell waste ChNPs can be a sustainable alternative while valorizing a regionally important aquaculture byproduct for antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxicity screening and (CMC)-chitosan hydrogel composite for post-harvest preservation altogether.

Limitations

Although the study offers valuable insights into the extraction, characterization and biological assessment of shrimp-derived chitosan nanoparticles, several limitations must be recognized. First, the antimicrobial assays were conducted only against selected bacterial (A. hydrophila, E. coli) and fungal (A. invadens, S. parasitica) strains. Conducting tests against a broader range of pathogens would provide a more complete picture of how well antimicrobials work. Second, cytotoxicity evaluation was limited to a single fibroblast cell line (NIH-3T3), which may not fully represent responses in other mammalian or fish cell lines. Third, the grape coating experiment was conducted in controlled laboratory conditions, and therefore, factors such as consumer acceptability, scalability and cost effectiveness were not evaluated. These limitations suggest that while the findings are promising, further in vivo research and application-based validations are necessary to confirm their wider applicability.

Conclusion

This study provides significant contributions to the field of aquaculture by showcasing an innovative approach to sustainably utilize shrimp waste, particularly from black tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon, highlighting the extraction of chitosan from shrimp shells, transforming what would otherwise be waste into valuable bio-based nanoparticles with numerous potential applications. The benefits for the aquaculture industry are multifaceted. First, by converting shrimp shell waste into chitosan nanoparticles, this work presents an eco-friendly solution to one of the industry’s major waste disposal challenges. These address environmental concerns associated with the accumulation of crustacean waste in aquaculture and provide a means to reduce its environmental footprint. Moreover, the study’s findings on the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan nanoparticles have direct implications for improving health and disease management in aquaculture. The nanoparticles demonstrated potent antimicrobial activity against common aquatic pathogens, which are often responsible for significant mortalities. The in vitro results suggest that ChNPs could be used as an alternative to traditional antimicrobials; however, it is too soon to say that they can be a direct substitute for antibiotics and antifungals in aquaculture. Further in vivo validation, including trials in aquatic organisms, evaluations of long-term safety, and investigations into scalability and cost-effectiveness, is essential to substantiate their practical usefulness.

Additionally, the biocompatibility of chitosan nanoparticles, as evidenced by cytotoxicity testing, suggests their safe use in various applications, including the development of functional coatings for food products, enhancing shelf life and reducing post-harvest spoilage. This could improve the overall sustainability of aquaculture production, contributing to better economic returns. Crucially, by offering a whole pathway from raw waste to functional nanoparticles together with in-depth structural, biological, and application study, this work closes earlier research gaps. It provides a scalable framework for repurposing local aquaculture waste, improving economic feasibility and sustainability.

References

Tacon, A. G., Hasan, M. R. & Subasinghe, R. P. Use of fishery resources as feed inputs to aquaculture development: trends and policy implications. FAO. 1018 (2006). https://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2008/639/

Hafsa, J. et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial proprieties of chitin and chitosan extracted from Parapenaeus longirostris shrimp shell waste. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 74, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharma.2015.07.005 (2016).

Kumar, M. N. V. R. A review of chitin and chitosan applications. React. Funct. Polym. 46, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1381-5148(00)00038-9 (2000).

Chien, P. J., Sheu, F., Huang, W. T. & Su, M. S. Effect of molecular weight of chitosans on their antioxidative activities in apple juice. Food Chem. 102, 1192–1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.007 (2007).

Yadav, M. K., Pokhrel, S. & Yadav, P. N. Novel chitosan derivatives of 2-imidazole carboxaldehyde and 2-thiophene carboxaldehyde and their antibacterial activity. J. Macromol. Sci. 57, 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/10601325.2020.1763809 (2020).

Ke, C. L., Deng, F. S., Chuang, C. Y. & Lin, C. H. Antimicrobial actions and applications of chitosan. Polymers 13, 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13060904 (2021).

Calvo, P., Remunan Lopez, C., Vila, J. L. & Jato Alonso, M. J. Novel hydrophilic chitosan polyethene oxide nanoparticles as protein carriers. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 63, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970103)63:1%3c125::AID-APP13%3e3.0.CO;2-4 (1997).

Carvalho, R., Duman, K., Jones, J. B. & Paret, M. L. Bactericidal activity of copper-zinc hybrid nanoparticles on copper-tolerant Xanthomonas perforans. Sci. Rep. 9, 20124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56419-6 (2019).

Pant, A. & Negi, J. S. Novel controlled ionic gelation strategy for chitosan nanoparticles preparation using TPP-β-CD inclusion complex. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 112, 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2017.11.020 (2018).

Rai, S. et al. Fabrication of alginate/chitosan composite beads for improved stability and delivery of a bioactive hydrolysate from shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) head. Food Sci. Nutr. 13(6), e70443. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.70443 (2025).

Eissa, M. E., Hendam, B. M., ElBanna, N. I. & Aly, S. M. Bee venom loaded chitosan nanoparticles enhances growth, immunity and resistance to Vibrio parahaemolyticus in pacific white shrimp. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 26179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11011-z (2025).

Devi, L. C., Putra, H. S. D., Kencana, N. B. W., Olatunji, A. & Setiawati, A. Turning Portunus pelagicus shells into biocompatible scaffolds for bone regeneration. Biomedicines 12(8), 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081796 (2024).

Pradhan, J. et al. Chitosan extracted from Portunus sanguinolentus (three-spot swimming crab) shells: its physico-chemical and biological potentials. J. Environ. Biol. 45(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/45/1/MRN-5186 (2024).

Yusan, L. Y., Paramita, S., Pramesti, E. P., & Nurmaningsih, K. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles 4% from blue swimming crab shell waste (Portunus pelagicus) against Staphylococcus aureus. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1473, No. 1, pp. 012054). (IOP Publishing, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1473/1/012054

Putri, S. E., Ahmad, A., Raya, I., Tjahjanto, R. T. & Irfandi, R. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles from black tiger shrimp shell (Penaeus monodon). Egypt. J. Chem. 66(8), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2022.148340.6417 (2023).

Abdel-Warith, A. W. A. et al. Using of chitosan nanoparticles (CsNPs), Spirulina as a feed additives under intensive culture system for black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 32(8), 3359–3363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.09.022 (2020).

Queiroz Antonino, R. S. C. M. et al. Preparation and characterization of chitosan obtained from shells of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei Boone). Mar. Drugs. 15, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15050141 (2017).

Mukheem, A. et al. Development of biocompatible polyhydroxyalkanoate/chitosan-tungsten disulphide nanocomposite for antibacterial and biological applications. Polymers 14, 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14112224 (2022).

Madhu, S., Devarajan, Y., Balasubramanian, M. & Raj, M. P. Synthesis and characterization of nano chitosan obtained using different seafood waste. Mater. Lett. 329, 133195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2022.133195 (2022).

Domszy, J. G. & Roberts, G. A. Evaluation of infrared spectroscopic techniques for analyzing chitosan. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 186, 1671–1677. https://doi.org/10.1002/macp.1985.021860815 (1985).

Liu, S. et al. Extraction and characterization of chitin from the beetle Holotrichia parallela motschulsky. Molecules 17, 4604–4611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules17044604 (2012).

Felix, C. B. et al. A comprehensive review of thermogravimetric analysis in lignocellulosic and algal biomass gasification. J. Chem. Eng. 445, 136730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.136730 (2022).

Chaudhary, P., Chauhan, S., Sharma, V., Singh, K. & Umar, A. Physico-chemical characteristics of amino acids in aqueous solution of amikacin sulphate. ES Mater. Manuf. 14, 95–109. https://doi.org/10.30919/esmm5f502 (2021).

Divya, K., Rebello, S. & Jisha, M. S. A simple and effective method for extraction of high purity chitosan from shrimp shell waste. In Proceedings of the international conference on advances in applied science and environmental engineering. 141–145 (2014). https://doi.org/10.15224/978-1-63248-004-0-93

Jena, K. et al. Physical, biochemical and antimicrobial characterization of chitosan prepared from tasar silkworm pupae waste. Environ. Technol. Inno. 31, 103200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2023.103200 (2023).

Oh, J. W., Chun, S. C. & Chandrasekaran, M. Preparation and in vitro characterization of chitosan nanoparticles and their broad-spectrum antifungal action compared to antibacterial activities against phytopathogens of tomato. Agronomy 9, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9010021 (2019).

Blois, M. S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 181, 1199–1200. https://doi.org/10.1038/1811199a0 (1958).

Mukhopadhyay, D. et al. A sensitive in vitro spectrophotometric hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay using 1, 10-phenanthroline. Free Radic. Antioxid. 6, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.5530/fra.2016.1.15 (2016).

Hisham, F., Akmal, M. M., Ahmad, F. B. & Ahmad, K. Facile extraction of chitin and chitosan from shrimp shell. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 2369–2373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.329 (2021).

Khan, T. A., Peh, K. K. & Cheng, H. S. Reporting degree of deacetylation values of chitosan: the influence of analytical methods. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 5, 205–212 (2002).

Povea, M. B. et al. Interpenetrated chitosan-poly (acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) hydrogels. Synthesis, characterization and sustained protein release studies. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2, 509 (2011).

Ladchumananandasivam, R., da Rocha, B. G., Belarmino, D. D. & Galv, A. O. The use of exoskeletons of shrimp (Litopenaeus vanammei) and crab (Ucides cordatus) for the extraction of chitosan and production of nanomembrane. Mater. Sci. Appl. https://doi.org/10.4236/msa.2012.37070 (2012).

Wenling, C. et al. Effects of the degree of deacetylation on the physicochemical properties and schwann cell affinity of chitosan films. J. Biomater. Appl. 20, 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885328205049897 (2005).

No, H. K. & Meyers, S. P. Preparation and characterization of chitin and chitosan—a review. J. Aquat. Food Prod. 4, 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J030v04n02_03 (1995).

Hargono, H. & Djaeni, M. Utilization of chitosan prepared from shrimp shell as fat diluent. J. Coast. Dev. 7, 31–37 (2003).

Woranuch, S. & Yoksan, R. Eugenol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles: I. Thermal stability improvement of eugenol through encapsulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 96, 578–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.08.117 (2013).

Kumari, S., Annamareddy, S. H. K., Abanti, S. & Rath, P. K. Physicochemical properties and characterization of chitosan synthesized from fish scales, crab and shrimp shells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 104, 1697–1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.119 (2017).

Pradhan, J. et al. Chitosan extracted from Portunus sanguinolentus (three-spot swimming crab) shells: Its physico-chemical and biological potentials. J. Environ. Biol. 45, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/45/1/MRN-5186 (2024).

Suryani, S. et al. Production of low molecular weight chitosan using a combination of weak acid and ultrasonication methods. Polymers 14, 3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14163417 (2022).

Boamah, P. O., Onumah, J., Agolisi, M. H. & Idan, F. Application of low molecular weight chitosan in animal nutrition, husbandry, and health: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 6, 100329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100329 (2023).

Gonçalves, C., Ferreira, N. & Lourenço, L. Production of low molecular weight chitosan and chitooligosaccharides (COS): A review. Polymers 13, 2466. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152466 (2021).

Rampino, A., Borgogna, M., Blasi, P., Bellich, B. & Cesàro, A. Chitosan nanoparticles: Preparation, size evolution and stability. Int. J. Pharm. 455, 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.07.034 (2013).

Liu, H. & Gao, C. Preparation and properties of ionically cross-linked chitosan nanoparticles. Polym. Adv. Technol. 20, 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.1306 (2009).

Coradeghini, R. et al. Size-dependent toxicity and cell interaction mechanisms of gold nanoparticles on mouse fibroblasts. Toxicol. Lett. 217, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.022 (2013).

Zhou, H. M. et al. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of a novel root repair material. J. Endod. 394, 78–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.026 (2013).

Loh, J. W., Saunders, M. & Lim, L. Y. Cytotoxicity of monodispersed chitosan nanoparticles against the Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 262, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.037 (2012).

Zheng, S. et al. Cytotoxicity of Triptolide and Triptolide loaded polymeric micelles in vitro. Toxicol. In Vitro 25, 1557–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2011.05.020 (2011).

Kumar, D., Sukapaka, M., Babu, G. K. & Padwad, Y. Chemical composition and in vitro cytotoxicity of essential oils from leaves and flowers of Callistemon citrinus from western Himalayas. PLoS ONE 10, e0133823. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133823 (2015).

Yao, Q. et al. Preparation, characterization, and cytotoxicity of various chitosan nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/183871 (2013).

Frigaard, J., Jensen, J. L., Galtung, H. K. & Hiorth, M. The potential of chitosan in nanomedicine: An overview of the cytotoxicity of chitosan-based nanoparticles. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 880377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.880377 (2022).

Confederat, L. G., Tuchilus, C. G., Dragan, M., Shaat, M. & Dragostin, O. M. Preparation and antimicrobial activity of chitosan and its derivatives: A concise review. Molecules 26, 3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26123694 (2021).

Valverde, J. M. et al. Novel edible coating based on Aloe vera gel to maintain table grape quality and safety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 7807–7813. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf050962v (2005).

Niu, C., Liu, L., Farouk, A., Chen, C. & Ban, Z. Coating of layer-by-layer assembly based on chitosan and CMC: Emerging alternative for quality maintenance of citrus fruit. Horticulturae 9, 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9060715 (2023).

Arnon, H., Zaitsev, Y., Porat, R. & Poverenov, E. Effects of carboxymethyl cellulose and chitosan bilayer edible coating on postharvest quality of citrus fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 87, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.08.007 (2014).

Chang, H., Li, K., Ye, J., Chen, J. & Zhang, J. Effect of dual-modified tapioca Starch/Chitosan/SiO2 coating loaded with clove essential oil nanoemulsion on postharvest quality of green grapes. Foods 13(23), 3735. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13233735 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Development of chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose edible films loaded with blackberry anthocyanins and tea polyphenols and their application in beef preservation. Food Hydrocoll. 164, 111198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.111198 (2025).

Chandrasekaran, M., Kim, K. D. & Chun, S. C. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. A review. Processes 8, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8091173 (2020).

Ristić, T., Hribernik, S. & Fras-Zemljič, L. Electrokinetic properties of fibres functionalised by chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles. Cellulose 22, 3811–3823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-015-0760-6 (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of Odisha, with a funding grant (4187/ST dated 05.11.2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Barsha Baisakhi: Investigation, data interpretation, formal statistical analysis, original manuscript writing. Jyotirmayee Pradhan: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, original manuscript writing & editing. Basanta Kumar Das: Supervision, review of manuscript. karmabeer jena: interpretation of the results, data analysis. Debasmita Mohanty: Carried out the anti-bacterial study. Swaleha Khatun: Preparation of edile coating composite. Stuti Ananta: Carried out antioxidant assays. Javed Akhtar: Carried out cytotoxicity study. Paital & Samar Gourav Pati: Molecular weight determination of chitosan.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

All data that support this study are included in the tables.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baisakhi, B., Pradhan, J., Das, B.K. et al. Penaeus monodon shell waste-derived chitosan nanoparticles show biocompatibility and broad antimicrobial activity. Sci Rep 15, 44157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27492-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27492-x