Abstract

System process mapping is essential for understanding complex systems and implementing effective management practices. In healthcare, mapping patient flow aims to reduce costs, improve the quality of care, and enhance efficiency. Process mining (PM) in healthcare is challenging due to the need for specialised knowledge and the inherent variability and complexity of healthcare processes. Comparing observed differences in patient flow pathways provides only a partial view; they must be combined with process outcomes and attributes for a comprehensive understanding. This paper proposes a combined stepwise approach using random forest (RF) and PM discovery to achieve outcome-centred process mapping from process-unaware systems. To this aim, we analysed the MIMIC-IV v2.2 dataset, containing healthcare data from patients at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) between the years 2008–2019. The MIMIC-IV dataset includes different types of sources within the hospital such as the emergency department (ED), patient measurements, procedures, transfer between departments, and intensive care units (ICUs). The results indicate that older patients with high ED priority and multimorbidity are particularly complex and challenging to treat, necessitating the implementation of tailored management strategies, in agreement with common clinical practice. A potential application of this approach is the real-time prediction of patients’ length of stay, which could optimise clinicians’ work, save healthcare resources, and improve the quality of patient care. Our approach can be applied to improve system process management by combining control-flow and data perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global healthcare systems are increasingly challenged by growing service demand and rising costs of patient care1,2. A major contributor to this burden is the increasing prevalence of chronic and non-communicable diseases, often co-occurring as multimorbidity, which significantly impacts care delivery and cost-effectiveness3,4,5. In this context, understanding the patient flow plays an important role in analysing patient movement through healthcare facilities and the associated operational logistics6,7. In particular, mapping patient flow is a valuable tool for identifying inefficiencies, evaluating the quality of care, and assessing overall hospital performance8,9,10.

Indeed, patient flow is influenced by factors such as socio-demographics and treatment complexity, often leading to deviations from standard clinical pathways11,12,13,14. Some deviations are warranted variations, driven by legitimate clinical needs or patient preferences15,16,17. Conversely, unwarranted, which arise from provider practices, resource disparities, or systemic inefficiencies can compromise care quality and resource use18,19.

To address such inefficiencies, healthcare organisations have increasingly adopted process improvement strategies over the years. Lean methodologies focus on reducing waste, while Six Sigma targets variability and errors. Both can be combined under the Lean Six Sigma framework to enhance care delivery20,21,22,23.

More recently, Process Mining (PM) - originally developed for industrial applications - has gained traction in healthcare for analysing and optimising care processes24,25,26. PM enables the discovery, validation, and enhancement of process models from event logs, which are structured records of sequential activities27. Among PM techniques, process discovery is the most widely used in healthcare and aims to automatically reconstruct real-life processes from event logs24. The event log building involves converting observed data into activities that will form the discovered process28. Another key technique, conformance checking, assesses how closely recorded events align with an expected or normative process model24,25. The process models that PM can discover and operate on can originate from either process-aware or process-unaware systems29,30. For example, logistics companies typically operate under well-defined process models, while hospitals, due to their complexity and fragmented data across units and systems, are often considered process-unaware31. This lack of a unified, explicit model results in highly variable process paths. A common challenge in analysing process-unaware systems is the ‘spaghetti effect’: a tangled, overly complex model with many interwoven paths, making interpretation and decision-making difficult32,33. This effect arises from the unstructured nature of events and the lack of predefined workflows that make the process difficult to interpret, analyse, or use for decision-making. Although no definitive method exists to fully eliminate the spaghetti effect, it can be mitigated through declarative modelling, which imposes higher-level constraints, or through techniques such as filtering, clustering, and aggregation33,34.

Hence, PM can identify key differences in process control flows; however, understanding their impact on outcomes requires additional targeted analysis35. This is where machine learning methods such as Random Forest (RF) can enhance PM by linking process characteristics with outcome variables. RF, an ensemble method of decision trees, has become a powerful tool in classification and regression tasks, widely used for its robustness and interpretability36,37,38.

Combining PM discovery and process outcome analyses, such as RF, under a single stepwise approach represents an opportunity to improve the interpretability of the process models automatically discovered with PM. Specifically, evaluating the relationship between process attributes and outcome can guide PM discovery by filtering attributes based on their impact on the outcome. Within this context, the aim of this paper is to propose a new stepwise approach based on RF and PM discovery to obtain a specific outcome-centred process mapping from an unaware-system such as the healthcare one.

In particular, combining PM with RF offers a novel opportunity: by integrating outcome-driven feature analysis into process discovery, it becomes possible to guide and refine the modelling process itself. Specifically, outcome-focused filtering of attributes can improve the clarity and relevance of discovered models.

In this paper, we propose a novel stepwise approach that integrates Random Forest with Process Mining discovery techniques to generate outcome-centred process maps from process-unaware systems, such as those found in healthcare. This method aims to reduce complexity, improve interpretability, and enable more targeted performance and outcome evaluations.

State of the art and problem description

System process mapping through techniques such as PM is helpful for a better understanding of complex systems and the adaptation of managing interventions39,40. PM techniques can be resumed in three main families41: discovery techniques, which have the aim to generate a process model from the events stored in log files, allowing the discovery of large and complex process automatically; conformance checking techniques, which allow to study and compare the deviations and similarities between a theoretical process model and the real process model; enhancing techniques, which have the purpose of improving and extending existing process. In the healthcare domain, the main techniques adopted are two: discovery and conformance checking25,26. Discovery techniques are used to monitor the management of patient care flow; on the other hand, conformance checking techniques are used for a model-checking perspective, comparing the real model with the guidelines or theoretical model.

E. Rojas et al.26 identifies two principal methodologies to perform PM and create an event log dataset, which represents the backbone to conduct PM analysis. The first methodology uses clustering techniques to conduct the analysis. This methodology is based on the clustering analysis of sequences42, which incorporates a series of activities to deal with an unstructured or spaghetti-type process. The second methodology is L*life-cycle Model43. It divides the PM workflow into five stages: plan and justify; extract; create the control-flow model and connect the event log; create the integrated process model; and provide operational support. This approach is suitable for a structured or lasagna-type process. Another approach, called process mining project methodology (PM2) can be used for both types of processes, structured and unstructured44. This methodology consists of three principal stages. The first stage focuses on (1) planning the research question and (2) extraction of data from the event log; the second stage is structured in (3) data processing, (4) mining & analysis, and (5) evaluation, and the last stage is represented by (6) process improvement & support.

Performing PM analysis in the healthcare context is challenging and demands a deep and specialised knowledge domain32,45. Specifically, in systems where processes are not strictly defined or standardised, the natural variability and complexity lead to a spaghetti-like process model28,46. To reduce the spaghetti-effect, user-defined techniques can be implemented33, such as aggregation, which combines similar activities or process steps to reduce the complexity of the process model; filtering, which removes less significant or infrequent activities and paths to focus on the core process flow; and clustering47, which groups related process variants to present a more structured and understandable view. All these approaches listed so far are based on the principle of process appearance optimisation, obtaining a better representation and interpretability of the process maps with a higher generalisation of the entire process model. A high level of generalisation may lead to an underfitting and an oversimplification of the process model that has an impact on the process analysis48,49; for example, errors or inefficiencies that occur infrequently may not appear in an overgeneralised model, reducing the ability to detect and address them and consequently providing a less detailed basis for decision-making, possibly leading to conclusions that don’t fully address underlying issues or optimise improvements or misalignment in understanding the process. Another important challenge is reported in the work conducted by Partington et al.35 which highlights that it is not sufficient to only compare the observed differences in patient flow pathways, but they should be combined with other comparative analyses on outcomes, such as the costs associated with patient flow pathways, to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the process.

Data mining and machine learning techniques, which are increasingly being applied across a wide range of healthcare domains50,51, could be integrated with PM analysis to address the above-mentioned challenges and can also support the analysis for multiple purposes52,53,54. For instance, they can support classification55 which has the aim to group similar events to construct higher-level activities, aiding in the discovery of simpler process models; prediction56 achieved by discerning relationships among process sequences, features, and business case characteristics; summarization57 to assess the impact of certain attributes or process behaviours on specific outcomes.

Within the healthcare system domain, a systematic literature review conducted by Palmer et al.58 identifies the length of stay (LoS), length of queues, and waiting times as main outcomes used to modelling patient flow among healthcare settings. The LoS of the patient flow is also one the most used outcomes for the effective planning and management of hospital resources59, and optimising LoS has two main purposes: firstly, it aims to meet the individual needs of patients by tailoring the level of care received60; for example, reducing LoS for a patient recovering from minor surgery without compromising care quality. Secondly, it contributes to the efficient management and planning of healthcare resources by decreasing LoS, thereby freeing up resources that could be allocated to other services and/or patients61. For instance, shorter LoS for certain treatments can allow for quicker bed turnover, enabling hospitals to accommodate more patients and reduce waiting times for critical care services. Stone et al.59 conducted a systematic review of the approaches and methodologies adopted to evaluate and predict the LoS. They chose 93 of 160 selected papers from 1970 to 2021 and identified 3 main approaches: statistical and arithmetic approaches such as regression models and regression tree models; these tools help to explore and analyse the association between LoS and factors such as comorbidities, age, and type of admission of the patients. The bootstrap-based model and RF models, which involve repeatedly resampling data to estimate the accuracy of a model and reduce variance, are also implemented to reduce the errors. Machine learning and data mining approaches are implemented to predict LoS from high-dimensional data represented by a high number of features. Neural networks and support vector machine represent the main tools to predict the LoS and require a training set and a test set of the data due to the adjustment of the hyperparameters, with the specific purpose of reaching the best accuracy of the model. A preprocessing step known as a multi-tiered data mining approach is also implemented for the prediction of LoS, and it aims to obtain clusters of patients with similar characteristics and predict the LoS for each group identified. Operational Research-Based approaches are also implemented to model patient flow and predict LoS, and among them, compartmental modelling, simulation modelling, and Markov models are the main tools adopted. The characteristics of these models are to highlight valuable insights into the data, describing the rate of the patient flow or the movements of patients through the hospital.

Considering all these premises, the possibility of filtering the process attributes with the awareness of the impact that the process attributes have on a specific process outcome may allow a closer and outcome-centred patient flow mapping and analysis based on the process outcome to be examined. To the best of our knowledge, RF and PM techniques have been applied from two distinct perspectives. Specifically, the RF technique is used to evaluate the association between the LoS and patient attributes59; separately, PM is implemented to evaluate and map patient flow, as well as to discover and ensure conformance with the clinical guidelines24.In this paper, we combine RF and PM, in particular, we aim to propose a new stepwise approach based on RF and PM discovery for obtaining a specific outcome-centred process mapping from an unaware-system such as the healthcare system. Specifically, the RF analysis to study the importance ranking of the process attributes on the primary process outcome such as LoS for directly filtering the process attributes and consequently obtaining a specific outcome-centred patient flow mapping with PM. This stepwise integration addresses a key challenge in process mining of healthcare data, i.e., overgeneralization, by using the importance scores derived from RF to filter event logs before the process model discovery. This outcome-centred filtering results in stratified process maps that retain interpretability while reducing noise, providing a clearer view of how patient flow patterns relate to specific outcomes.

To prove our goal, we used as a case study the MIMIC-IV v2.2 dataset, containing healthcare data from patients at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) between the years 2008–2019 such as the emergency department (ED) information, patient measurements, hospital admission information, and transfer between departments.

Methods and use case

Proposed approach

PM2 methodology stands out as a comprehensive framework designed to systematically apply PM techniques to research questions. The relationship between PM2 and PM practices is one of complementarity and integration44, and it serves as an overarching guide to ensure that all PM analyses are applied effectively and cohesively. By embedding different PM techniques within the structured phases of PM2, practitioners can leverage the strengths of multiple methodologies and achieve a more comprehensive understanding of processes. Thus, PM2 harmonises PM methodologies, creating a synergistic effect that improves process analysis. RF is a machine learning method and an ensemble technique that combines multiple decision trees to produce accurate and robust predictions37. It is largely used for classification and regression tasks, such as classifying data into different categories, or it can predict continuous values. RF can also determine the importance of different features in the dataset, and this helps in understanding which features have the most impact on the prediction, which can be useful for feature selection and understanding the underlying data38.

The rationale behind our approach lies in RF’s capability to determine the importance of different process attributes in predicting the process outcome; therefore, the co-joint implementation of RF and PM techniques can be used for obtaining a ranking of the most important process attributes that have an impact on the process outcome, and filtering the event log with specific process attributes characteristics to visualise specific outcome-centred process mapping. After performing the PM discovery, it is possible to evaluate the process control flow and time performance, as well as check the conformance between process models with specific outcome-centred characteristics. Similar to PM2, our approach is organised into sequential stepwise phases to ensure a thorough and systematic application (Fig. 1):

Phase 1: data management and process abstraction. In this first phase, the focus is on organising the data and processes involved. We have divided phase 1 into three main steps. Step 1 consists of the selection and management of the data from several datasets which contain detailed and different types of information. Step 2 focuses on the abstraction of the process, which means organising the entire information collected in a process starting with the simplest and most general level of abstraction, then progressively moving into more detailed aspects. Finally, step 3 is about event log building, which includes three actions: (A) setting a primary business goal, (B) identifying the key activities essential for the process, and (C) selecting the appropriate process instance level. This phase lays the foundation for a structured approach to data handling, process organisation and abstraction.

Phase 2: fixing the process outcome, attributes, and analysis. This phase aims to identify the process outcome to be analysed and the process attributes. Once identified and declared in steps 1 and 2 the process outcome and the process attributes, in step 3 is necessary to merge in a unique table all the information collected using unique key IDs. This step is fundamental to analyse the distribution of the process outcome and attributes during step 4 and their relation in the following phase 3.

Phase 3: Importance analysis: attributes selection. Phase 3 is characterised by RF analysis, using the process outcome as the dependent variable and the process attributes as independent variables. The analysis begins with step 1, where the data is split into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%). In step 2, it is possible to optimise the model’s hyperparameters using the training set, and in step 3, the accuracy of the model obtained can be tested using the test set. Finally, the importance of each process attribute can be determined, and select the attributes with the highest score rank.

Phase 4: analysis of the attributes selected and event log filtering. After the selection of the highest score rank of the process attributes in phase 3, the following phase 4 is characterised to analyse the process attributes selected considering the process outcome. Categorise the process outcome, if it is a continuous variable, is useful to stratify the distribution analysis of attributes in specific groups. For instance, if you decide to categorise the process outcome on the basis of the 1 st and 4th quantiles, you can explore how the process attributes are distributed in these two groups. Once analysed the distribution of the attributes selected in step 1, in the following step 2 it is possible to identify specific features of the selected attributes observed between groups, which can be used during step 3 for filtering the event log.

Phase 5: process mining analysis: control flow discovery, performance analysis, and conformance checking. After filtering the event log by specific features of the selected attributes in phase 4, during phase 5 it is possible to perform PM analysis. The first analysis conducted in step 1 is the discovery of the direct followed graph to analyse and explore the behaviours of the process. In step 2 the control flow analysis and the time performance analysis are useful for understanding the characteristics of the entire process, and the model discovery and the conformance checking in step 3 are aimed at discovering the general process with the inductive miner algorithm to evaluate the model simplicity and comparing the discovered model between groups with specific features.

Use case

We identified the MIMIC-IV dataset as a suitable use case for several reasons: I-The dataset matches our background and aim, containing information that reflects the complexity of real processes that could occur in a hospital. II-The PM perspective is already implemented and well-studied in MIMICEL project62, which has been used to successfully generate an event log to capture an end-to-end and analyse the existing patient flows in ED. III-The MIMIC-IV dataset is free and accessible, allowing the reproducibility and shareability of the method proposed. IV-The privacy of patients is guaranteed by full data anonymisation, and PM can be performed without violating privacy concerns. We aim to validate the proposed approach using the MIMIC-IV dataset to obtain a specific outcome-centred process mapping from a complex, unaware system such as the healthcare system.

The MIMIC-IV dataset

The MIMIC-IV v2.2 dataset is one of the largest accessible datasets containing healthcare data from patients at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) between the years 2008–201963. The dataset incorporates different types of sources within the hospital such as the ED, patient measurements, procedures, transfer between departments, and intensive care units (ICUs). The entire dataset is organised in relational tables grouped in 6 modules (ED, Hosp, ICU, CXR, ECG, and Note) and includes more than 299,000 patients, 431,000 hospital admissions, and 73,000 ICUs stays. The main modules are represented by the ED module which contains around 425,000 ED stays with several types of information such as vital signs, triage, medication reconciliation, medication administration, and discharge diagnoses; the Hosp module covers data from laboratory tests, patient demographics, hospitalizations, and intra-hospital transfers; the ICU module includes intravenous and fluid inputs (inputevents), ingredients for the aforementioned inputs (ingredientevents), patient outputs (outputevents), procedures (procedureevents). All tables are linked by 3 main key IDs allowing the identification of patients, stays events in the ED, and event admission into the hospital.

The sequential stepwise phases of PM2 described above have been adapted to MIMIC data as following:

Phase 1: data management and process abstraction. The approach starts with the selection and management of the data contained in each relational table of the main MIMIC-IV modules, with the specific aim of building the event log for PM analysis and the table of attributes for each case. We took into account the MIMICEL62 that had already implemented a method for the event log building for the ED module, and we extended and adapted the same approach for the Hosp and ICU modules. This step is essential for abstracting the processes, focusing on patients who first access the ED. We abstracted 4 main processes: (1) the transfer process describes the patient flow through the hospital, for instance, when a patient enters the ED may either be discharged or admitted to the hospital. If admitted, the patient might be transferred to one or more different units before eventually being discharged, or they may be discharged directly from the initial unit. (2) The detailed transfer process is derived from the transfer process by specifying the hospital units where patients are admitted and discharged. This activity label enrichment helps highlight admissions to and discharges from specific hospital units. In this particular abstraction, we focus only on the group of patients who are admitted to the hospital after being discharged from the ED, providing a clearer view of these specific cases. (3) The ED management describes the flow of patients within the ED, detailing activities and movements during their ED stay. (4) The hospital management process represents the flow of patients within the hospital after their stay in the ED, covering the subsequent phases of their hospitalisation.

Regarding the event log building we started from (A) Set a primary business goal. The main goal is to obtain an overall understanding of the patient flow when a patient enters through the ED. Specifically, this phase aims to capture the physical, end-to-end movement of patients within the hospital, based on data from the MIMIC-IV dataset. The benefit in reaching this goal is tracking the patient flow from the highest level of generalisation of the entire process to the specific ones such as ED or hospital admission and evaluating the process outcome: the patients’ LoS in the next steps. Next, we followed with (B) Identify key process and activities. This step involves recognising the activities involved at different levels of abstraction. In our work, we use patient records to build 4 granularity levels: the first level describes where patients are located throughout their hospital visit; the second one is more specific, describing the exact units where patients are admitted and discharged; The third level is represented by ED management, and we used the MIMIC-EL framework to aggregate duplicate activities that share the same timestamps. Concerning the fourth level, the hospital management counted the following information: hospital admission and discharge, hospital services requested, lab events, microbiology lab events, pharmacy, and ICU events (imputevents and outputevents). Before to proceed further in (C) Select process instance levels, we considered that MIMIC-IV is structured in relational tables and linked to each other with main 3 key IDs: subject_id refers to a specific patient, stay_id describes the patient stay in a specific department or hospital unit, hadm_id refers to a specific admission into the hospital. For our purposes, we needed to obtain a unique stay_id from the ED acceptance to the ED or hospital discharge enabling us to distinguish multiple stays from the same patient. For this reason, we create another unique stay_id equal to the stay_id assigned from the ED that never changes during the patient visit until the patient is discharged from the ED and not admitted into the hospital or discharged from the hospital after the admission. An event log is a collection of process instances (cases) and in this step focuses on the cases levels in the event log. All the abstracted levels of processes are designed considering the patient flow, specifically when the patient physically goes to the hospital and leaves the hospital structure. For this reason, we select as instance level the unique stay_id for the transfer process, the stay_id in ED for the ED management process, and hadm_id for the hospital management process. In the case of admitted patients for the detailed transfer process, we considered the hadm_id as process instance level. Further datils for these steps are reported in Supplementary code material developed in SQL language.

Phase 2: fixing the process outcome, attributes, and analysis. The phase 2 is dedicated to fixing the process outcome to explore and drive the entire PM analysis. We chose LoS as process outcome and we estimated the LoS for each instance (case) and process abstracted. Consequently, we obtain 4 specific LoS: the total LoS which describes the period of time when the patients enter the ED and are discharged from the ED or the hospital after the admission; the admitted LoS which represents the entire time period for those patients that first enter in ED and subsequently are admitted into the hospital and discharged; the LoS in ED which refers to the time period spent during the stay in ED whether they are admitted to the hospital or discharge; and finally, the LoS in hospital which defines the time period spent into the hospital from the hospital admission to the hospital discharge. We also selected the attributes for each instance adding information that can enrich the event log. In this step we merged all the information in a single table, composed by the characteristics of patients such as sex, age, and race; ED information such as arrival transport, acuity, which refers to the priority assigned during triage on a scale from 1 to 5, disposition, which indicates whether the patient is discharged or admitted to the hospital, and pain level, rated on a scale from 0 to 10; hospital information such as the type of first service requested, which is the clinical specialty assigned to the patient upon arrival, and the type of insurance. Moreover, we also accounted for the presence of multiple diseases (multimorbidity) in the patients by calculating the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) and the Elixhauser comorbidity index (ECI)64,65,66 from the billed diagnosis in ED or hospital or both for patients admitted to the hospital. At the end of phase 2, we analysed the 1 st and 4th quantiles of LoS for each process to obtain two groups: the first one represents the shortest instances (low LoS) and the other one represents the longest (high LoS).

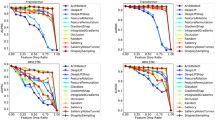

Phase 3: random forest for the importance of attribute and analysis. The phase 3 is characterised by the RF analysis performed on the label groups, low Los or high Los, and the attributes extracted in the previous phases with the specific aim to analyse the importance of the attributes to evaluate their impact on the specific LoS for each process considered. Each RF model was performed with the inner-validation, useful to set the best hyperparameters in the training set, and consequently, the outer-validation of the trained model was evaluated with the test set, estimating accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the RF models. The training and test sets were obtained by splitting each sample randomly into 70% and 30% respectively.

Phase 4: analysis of the attributes selected and event log filtering. We selected the first 3 highest attributes for importance, considering both criteria: mean decrease accuracy and the mean decrease in Gini coefficient for each process considered (Table 1). In the end, we obtained 5 groups of top attributes for importance, and we analysed their distribution in each group and process. This phase is useful to get more information about the process, focusing on the LoS as a process outcome. Indeed, analysing the main characteristics for each group that have the highest importance to predict the shortest and longest LoS has the advantage of driving the following PM analysis by filtering the event log with the specific features of attributes that have an impact on the process outcome. At the end of this phase, we filtered the entire event logs with specific features of attributes for each process considered according to RF results.

Phase 5: process mining analysis. We performed the direct followed graph and the control flow analysis in terms of frequency and time performance, consequently we followed the analysis with the discovery of the models with the inductive miner algorithm for each group (low LoS and high LoS) selected in phase 4 and processes abstracted in phase 1 to assess the model simplicity, used to evaluate how easy a process model is to understand. Therefore, we proposed the conformance checking perspective as the final analysis, completing the two main PM perspectives for health, discovery, and conformance25. By fixing the discovered model process one step at a time, it is possible to perform conformance checking using the event log of each group, low and high LoS, at the same process abstraction level, estimating the 3 main conformance indexes: fitness, precision, and generalisation48. Fitness measures how well the observed behaviour in the event log fits the behaviour allowed by the process model. In other words, it evaluates whether the traces in the event log can be successfully replayed on the process model. The core idea of precision is to measure how much the process model allows behaviour that is not seen in the event log. If a process model allows a lot of behaviour that never actually occurs in reality (in the event log), then the precision of the model is low. Conversely, if the process model restricts its behaviour closely to what is observed in the event log, its precision is high. Generalisation measures how well the process model generalises and evaluates whether the model can handle variations that were not present in the event log but are likely to occur. A high value means that the model can handle new instances that were not explicitly observed in the event log but are reasonable given the existing behaviour in the event log.

Software and packages

We used Postgres v. for managing relational tables and constructing the event log; R v.4.1.2 and packages67,68,69,70 facilitated random forest analysis and overall data exploration and data description; Python v.3.12.6 and packages71,72 enabled process mining analysis.

Results

General characteristics and ranking of attributes

At the end of phases 1 and 2, we obtained 4 types of processes abstracted and 5 event logs, and we obtained more than 200,000 subject_id, 420,000 stay_id, and 200,000 hadm_id. The event logs cases are characterised by a sex distribution between females and males of 54% and 46% respectively, a mean age of 50.3 (SD: ±20.1) years, and a race distribution of 58% White, 22% Black, 8% Hispanic, and 4% Asian.

Regarding the principal ED attributes, most of the ED patients were walk in patients (59%), 37% arrived by ambulance, 0.5% by other means and 4% had an unknown mode of arrival. The patients have a median acuity of 3 [25th :2–75th :3] and a median pain of 4 [25th :0–75th :8]. Less than 1% of the ED patients had a loss of consciousness or respiratory failure. The 37% of patients received admission to the hospital as disposition from the ED, and the principal type of service requested is general service for internal medicine 67%, followed by non-surgical-cardiac admissions 7%, general surgical service 6%, non-surgical-brain 4%, and non-surgical- musculoskeletal system (4%). Along 11 years of observation, each patient had in median 3 [25th :1–75th :7] stays in ED and 1 [25th :0–75th :4] admission to the hospital, with a median LoS in ED of 5.5 h [25th :3.5–75th :8.3] and 64.0 h [25th :19.8–75th :126.0] into the hospital. Further details are reported in Supplementary material, Appendix A and B (Appendix Table S 1 - Appendix Table S 4).

During phase 3 we performed the RF analysis to obtain the importance ranking of the principal attributes selected for each level of the process abstracted. We obtained good accuracy from the outer-validation for the models, ranging from 75% to 92%. We also obtain reasonable measures for sensitivity and specificity, shifting from 79% to 90% and from 71% to 94% respectively. We reported the principal attributes selected in phase 4, which have an impact on the LoS, and the mean decrease accuracy and Gini importance measure in Table 1. We also described the filtering criteria chosen for the instances for the following PM analysis, on the base their distributions by median or quantile or mean or frequencies. Appendix C (Appendix Table S 5 - Appendix Table S 20) of the Supplementary material reports the detailed results achieved with the RF analysis; instead, Section D (Appendix Table S 21 - Appendix Table S 27) reports the detailed distribution of the attributes selected for each group.

Control flow and time performance perspectives

Previously, we reported the results that allowed us to obtain more information and awareness for each process abstracted, considering the LoS as the central process outcome. Precisely, we analysed which are the attributes that have the highest impact on the LoS; moreover, based on the distributions of each attribute selected for those patients that had a low and high LoS (1st – 4th quantiles), we selected specific attributes and characteristics useful to filter the entire event logs for the PM analysis. This process allows us to obtain for each process 2 event logs that belong to patients with specific attributes that have an impact on determining a low (short) and high (prolonged) LoS.

Considering the general transfer process, we selected 83,059 and 29,598 cases for the low and high LoS total. The median LoS observed in the low group is 4 h and 118 h for the high group. The direct followed graph with the absolute frequencies and time performance information is represented in Figs. 2 and 3. 90% of the low LoS group accessed the ED and were discharged from the ED; instead, for the high LoS group 79% of cases experienced the following path: entered the ED, ended up admitted to the hospital and then discharged from the hospital or transferred (one or more transfer) to another unit before being discharged from the hospital. The time performance analysis shows that in general, the high LoS group has a longer median time period between pairs of transitions, except for the transition enter the ED and admitted to the hospital for which the median time for high and low LOS groups is 5 h and 8 h respectively.

With regard to the hospital admission units and discharge units, we observed that 4% of the 10% of cases in the low LoS group are admitted to ED observation only compared to the 3% of the 79% of cases in the high LoS group while the rest of patients in the high Los group are admitted to the hospital and principally to general medicine 13%, cardiology 5%, surgery 4% hematology/oncology 3%, and neurology 2%.

We also represented the detailed transfer process abstraction focusing only on those patients who had a hospital admission, requested general service for internal medicine (MED) as the first hospital service, and in a specific hour for the hospital admission, 8–12 and 16–20 h respectively. After filtering the event log, we obtained 4,981 cases for low LoS with 16 h as median time performance, and 6,279 cases for high LoS with 110 h. We observed 126 paths for the low group and 639 paths for the high group. 91% of the paths for the low group follow the admission to ED observation and discharge; instead, only 6% of the paths for the high group follow the admission to ED observation, and the others are admission in medicine 32%, or other units such as ICUs. Even though many of the low group patients were admitted to the hospital, many first underwent ED observation, waiting for an available specific hospital ward to be assigned. In general, we observed the same phenomenon described in the transfer process: the time period from the enter in ED and the following hospital admission is longer in the low group compared to the high one, but the trend is reversed considering the time period between admission and discharge from the hospital.

Concerning the process management in the ED we select patients who arrive walk in the ED and other characteristics such as acuity and ECI levels. After filtering the event log, we obtained 151,215 cases for the low group and 23,682 cases for the high group. The median LoS in ED for the low group was 4 h and 6 h for the high group. We observed a large number of pathway variations in both groups, with 16,648 distinct paths in the low LoS group and 11,235 in the high LoS group. The median time performance differences of the most frequent paths observed are almost 1 h between the low and high groups; moreover, we did not observe so many differences in the median time execution of pairs of activities between low and high groups, but we noticed that the high group, in median, is faster for few minutes in the execution of the first activities, and this trend change during the execution of the last activity before to be discharged from the ED.

Regarding the management in the hospital, after filtering the event log, we obtained 5,382 cases for the low group and 8,408 cases for the high group. The median time performance for the low group is 0.43 h and 155 h for the high group; this difference is mainly because patients in the high LoS group typically require hospitalisation for several days and often need admission to ICUs, reflecting the greater complexity and severity of their clinical conditions. We observed high differences in both the number and median length of paths between the low and high groups—362 vs. 7,600 distinct paths and a median length of 12 vs. 32 activities, respectively. The most common paths in the low groups are represented by hospital admission and hospital discharge, or alternatively, in-hospital laboratory test (one or more), hospital admission, and then hospital discharge. Given the high number of path variations in the high group, it was difficult to identify a common path; however, while the most frequent paths in the low group ranged between 80% and 2% of cases, the high group ranged from 4% to less than 1%. We also observed that the relative frequency of the input events and output events activities was higher in the high group. The detailed results for the control flow and time perspectives are reported in Supplementary material, Appendix E (Appendix Figure S 1 - Appendix Figure S 20 and Appendix Table S 28 - Appendix Table S 48).

Discovery and conformance checking perspectives

We completed the PM analysis with the discovery and the conformance checking of the models for each process abstracted and group selected. In Supplementary material, Appendix F (Appendix Table S 49 and Appendix Figure S 21 - Appendix Figure S 30) contains the full list of results obtained. We measured the comprehensibility of the discovered models with the simplicity index, and we obtained that transfer, management in ED, and management in hospital models had an index ranging from 64% to 78%; instead, detailed transfer models had the lowest index, varying from 40% to 43%. We also measured the conformance checking indexes: fitness, precision, and generalisation, reported in Supplementary material, Appendix G (Appendix Table S 49 - Appendix Table S 54). The fitness measure was almost 100% for each model and related event log. This score grade is expected considering that the processes generated from unaware systems were spaghetti-like. Analysing the same model discovered with related low and high event logs, we observed that the highest differences in precision were in the management hospital model; instead, the highest generalisation differences are observed in the detailed transfer model.

Discussions

In this study, we applied a new stepwise approach based on RF and PM discovery for obtaining a specific outcome-centred process mapping from an unaware-system such as the healthcare system, using as case study the MIMIC-IV v2.2 dataset. Specifically, we focused on LoS as the main outcome variable, using it as a lens through which to evaluate and compare the discovered process patterns. The analysis revealed distinct pathways and characteristics associated with different LoS profiles, offering insights into the operational and clinical factors that may influence hospital throughput and patient care efficiency. Although the overall process remains highly spaghetti-like, the combined use of RF and PM enables us to disentangle and compare patient flows for low- and high-LoS groups, revealing insightful patterns. Considering the general transfer process, patients in the low-LoS group tend to be younger, with low multimorbidity and low ED priority, and are discharged from the ED within three hours—most to ED observation—whereas those in the high-LoS group are older, have high multimorbidity and ED priority, experience a median ED stay of five hours followed by a two- to three-day hospital admission (mainly to general medicine, cardiology, surgery, hematology/oncology or neurology). Focusing on the detailed transfer process, patients who were admitted to the hospital and required general internal medicine services are characterised by specific admission times: 8:00 to 12:00 for short LoS and 16:00 to 20:00 for prolonged LoS. Most of the short LoS patients are admitted to the ED observation unit and discharged within a median of 16 h. In contrast, patients with prolonged LoS are primarily admitted to internal medicine units, with a median stay of 89 h, or to other units such as ICUs.

In the specific case of the process management in the ED, for patients who arrived by walk, the short LoS group is characterised by a lower priority in ED and a lower multimorbidity compared to the prolonged LoS group. The short LoS group is discharged, in median, within 4 h from the ED access; differently, the prolonged LoS group takes in median 6 h to be discharged. The paths of activities were similar between the two groups, but the prolonged LoS group was slower during the execution of the last activities before being discharged from the ED compared to the short LoS group. Concerning the process management in the hospital, for patients admitted who required general internal medicine services, in the short LoS group, the most common pathways involve either hospital admission followed by discharge or hospital admission and discharge after one or more laboratory tests, with a median stay of 13–15 h. On the other hand, the high variability of pathways in the prolonged LoS group makes it challenging to identify a common pattern, indicating the extreme complexity of the process in the hospital with these characteristics and making the patient flow unique and incomparable to the other ones.

Considering all the processes abstracted, we identified that multimorbidity significantly affects LoS, highlighting the complexity of managing patients with multiple chronic conditions. The observed impact of multimorbidity on LoS is well-supported by existing research, highlighting the difficulties in treating patients with numerous chronic illnesses73,74,75. Additionally, the acuity in ED of the patient’s condition at the admission appears a critical factor in predicting the LoS. A low acuity and consequently a high ED priority level correlate with a longer LoS but a shorter median time to hospital admission, compared with high acuity and low ED priority level; this relationship is already documented in the literature76,77,78. Age also played a notable role, older patients generally required extended LoS, in agreement with previous studies79,80,81,82. Furthermore, there are specific attributes that can impact the LoS differently in the ED and in the hospital. For example, the arrival transport has a high impact on the LoS in ED and it is associated with a higher triage urgency score83,84,85. Concerning the hospital, the type of service requested, and the admission time have an impact on the LoS. Chrusciel et al.82 show that some services requested after the ED have an impact on LoS in the hospital such as geriatric medicine, rheumatology, gastroenterology hepatology, and internal medicine. The admission time in the hospital during the day (8:00–12:30), afternoon (12:30–17:00), and late afternoon or night (17:00–8:00) also has an impact on the LoS, as reported by Earnest et al.86. The attributes selected in our study that have an impact on the LoS are broadly supported by the existing literature. Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Gokhale et al.87 on prediction variables and methods used in tools that predict the risk of prolonged LoS show that 68% of studies selected identify as prediction variables the main 3 attributes selected in our study: multimorbidity, acuity, and Age; and the 60% of the studies selected the other 3 specific attributes: arrival transport in ED, type of service requested, and admission time in hospital.

The process abstraction used in this paper follows a scheme introduced in the MIMICEL study62, which is specific for constructing event logs in the ED. We then adapted this approach for patient transfers and hospital management. In a recent study conducted by Park et al.88 a new methodology for process abstraction has been proposed to standardise healthcare data according to the CDM model. The MIMIC data cannot be manipulated and standardised according to the CDM model because they are already anonymised. Considering the customisation of the processes abstraction it is difficult to compare the results obtained from the control flow and the conformance checking analysis with other studies.

Evaluating the conformance checking indexes obtained, the fitness measure is almost 100% for each model and related event log, which means that the traces in the event log can be successfully replayed on the process model considered. Processes generated from unaware systems are expected to be spaghetti-like and this phenomenon facilitates the execution of traces successfully28. The detailed transfer models have a low precision and a good generalisation, which means that the process model allows a lot of behaviour that never actually occurs in the event log, and it can handle variations that were not present in the event log but are likely to occur. This effect may be associated with the high number of hospital units; instead, the other models have a good precision and generalisation score indicating that the process model restricts its behaviour closely to what is observed in the event log and can handle new instances that were not explicitly observed into the event log but are reasonable given the existing behaviour. Lastly, taking into account the simplicity and precision scores the best representative models that we obtain are transfer, management in ED, and management in hospital models. A good precision and simplicity score allows a better representation of the actual process because if the model is too permissive, it might represent a more flexible process than it is in reality. Analysing the precision scores obtained for the transfer, ED management, and hospital management models, and comparing the respective short and prolonged LoS event logs, we observe no differences for the transfer model, suggesting comparable model behaviour. On the other hand, there is a notable difference of nearly 10% when comparing the short LoS ED management model with the prolonged LoS event log, and vice versa. This difference is at least 40% for the hospital management models. These results highlight a difference in model behaviour between short and prolonged LoS for both ED and hospital management models.

Overall, these results suggest that older patients with a high ED priority and high multimorbidity are complex patients and more challenging to treat, necessitating the implementation of tailored management strategies. Such complexity in older patients can lead to prolonged hospital stays, and consequently increased resource utilisation59. The healthcare systems should consider integrating comprehensive assessments into the standard care protocols for older patients providing a multidimensional evaluation of a patient’s status. This holistic approach can help identify the specific needs of each patient for more personalised and effective interventions89,90. Moreover, multidisciplinary teams should be involved in the care of these patients and work collaboratively to develop and implement care plans that address the various dimensions of patient health91,92. Additionally, older patients with high ED priority and multimorbidity have complex medical histories that cannot be fully captured during ED visits93. For this purpose, communication and care coordination between ED and primary care providers is crucial for more informed decisions and improving overall patient outcomes. The results obtained from our proposed approach identify the attributes that impact on a process outcome, such as LoS, and analyse the related tailored patient flow. By combining process outcome and patient flow pathway analysis using a stepwise approach based on RF and PM discovery, it is possible to obtain a specific outcome-centred process mapping from an unaware system, such as the healthcare system, for a more comprehensive understanding.

Process mining applications, especially in domains such as healthcare, may target specific cohorts or even individual process instances24, so the notion of “minimum sample size” may not strictly apply. Nevertheless, it is possible to provide a statistical perspective on the amount of data required to ensure that the event log contains sufficient behavioural information for process discovery. Cai et al.94 defined the probability that a newly observed trace introduces new process behaviours (e.g., a new variant or transition), providing a statistically grounded stopping criterion for large event logs. In particular, a log is considered ε-discovery sufficient if the probability that a newly observed trace introduces new process behaviours is below a given threshold ε. For Random Forest models, the minimum number of observations depends on the complexity of the problem, the number of features, and the variability of the data. For practical purposes, model adequacy can be evaluated through learning curves95, which assess whether the model’s performance has stabilised or adding more samples could improve it. In our case, the MIMIC dataset provides a fixed number of observations, and we optimise the model’s hyperparameters to minimise prediction error over 1,000 iterations, splitting the dataset into 70% for training and 30% for testing. Considering that our approach is based on the combination of RF and PM analyses, we recommend assessing the adequacy of the RF model using learning curves before proceeding with the PM analysis.

The main advantages to adopt the approach presented in this paper are: (a) Obtaining a stratified process maps focused on specific process outcome measure by combining RF and PM framework analysis in a unique stepwise approach. (b) Identifying the main attributes that impact most on the process outcome and directly analysing the type of process these key attributes define. (c) Although the represented processes remain spaghetti-like, the stratification analysis between groups allows to compare pathways and pairs of activities and therefore capture the main differences in outcome-centred processes generated from unaware system.

Unlike standard PM approaches that often produce highly generalised or spaghetti-like models from process-unaware systems, our approach introduces a guided stratification method. By identifying and ranking process attributes based on their impact on the outcome (e.g., LoS), we filter and split event logs before conducting PM discovery. This pre-processing step minimises overgeneralization and results in process models that are simpler, more interpretable, and tightly connected to relevant clinical outcomes. This work contributes methodologically in three key ways: (a) it enables stratified process maps focused on specific outcome measures by combining RF and PM in a unified stepwise framework; (b) it identifies the attributes that most impact process outcomes and uses these to define and compare subgroups within the overall process; (c) it allows the detection of meaningful differences in control flow and performance, even when the underlying system produces inherently spaghetti-like models.

While it is true that existing methods can identify relevant factors or generate process maps, they generally treat these as separate tasks. Our approach differs by explicitly using outcome-driven feature importance to filter and guide PM discovery. This integration avoids generic overfitting and provides outcome-specific process insights. In doing so, it offers a clearer interpretation of how particular patient profiles influence process variability - an advantage over traditional PM that lacks this outcome-centred stratification. Finally, the integration of RF and PM discovery into the analysis provides a robust framework and can help in forecasting patient needs, identifying high-risk patients and implementing preventative measures to reduce hospital admissions and resources.

The broad implications of the proposed approach in research and healthcare settings are potentially significant for more effectively designing strategies to improve efficiency and quality in healthcare delivery. For example, by identifying the attributes that impact process outcomes and analysing patient flow, healthcare providers can allocate resources more efficiently. This ensures that critical areas receive the necessary attention, reducing bottlenecks and improving overall service delivery. Furthermore, understanding the specific pathways and outcomes for different patient groups allows for more personalised care plans. Tailored interventions can be designed to meet the unique needs of patients, particularly those with complex conditions, leading to better health outcomes. Finally, healthcare administrators and clinicians can make more informed decisions based on comprehensive data insights and make strategic planning, policy-making, and operational adjustments that align with the goals of improving patient care quality and operational efficiency.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It employs a comprehensive approach to provide a detailed understanding of patient flow and process outcomes. This holistic analysis highlights the importance of process attributes on process outcomes selected to drive the PM analysis for an outcome-centred evaluation. Moreover, using different levels of abstraction, from the simplest, such as the transfer model, to the most complicated, allows us to obtain more insightful and tailored results and model representations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that combines PM and RF to analyse the flow of patients starting from ED; additionally, the methodology has the potential for broad application across various datasets generated from process-unaware systems, such as healthcare systems, supporting informed decision-making through comprehensive data insights. The use of the MIMIC dataset, which is accessible, and the Supplementary code material ensures that our results can be reproduced and used by other researchers.

However, the study also has some limitations: first, some factors that could impact on LoS are not accounted for in the study due to the nature and anonymisation of the MIMIC dataset. These include the days of the week and holidays, the crowding levels, and the number of available beds for ED and hospital units. These factors could potentially influence the outcomes, and their absence in the analysis may limit the comprehensiveness of our findings. Nevertheless, the trend of our findings is supported by the existing literature and common clinical experience, confirming the importance of some process attributes on the process outcome LoS. Second, the preprocessing choices proposed in our stepwise approach, including the definition of events and thresholds for LoS, may introduce bias or information loss, and for this cause our approach requires further validation across different datasets and healthcare settings. Despite its strong predictive performance, RF does not directly compute the temporal dimension of the data, which can be a limitation in contexts such as patient flow, where the sequence of events is crucial. Lastly, a major limitation of PM is its dependence on high-quality, complete event logs; missing, inaccurate, or inconsistently recorded events can lead to incomplete or misleading process models.

Conclusions and future work

In conclusion, the primary methodological contribution of our study lies in combining Random Forest’s feature-ranking capabilities with Process Mining discovery in a unified, outcome-centred workflow. This enables targeted filtering of event logs based on statistically significant predictors of the process outcome, which enhances specificity, reduces overgeneralization, and improves the practical interpretability of complex process models generated from process-unaware systems.

Future work will focus on enhancing the robustness and applicability of our approach. Further validations are required across datasets related to different frameworks to verify the applicability and scalability of the proposed approach, and outcomes, such as costs and consumption of resources. Furthermore, the possibility to improve this analytical approach in real-time will be crucial. For instance, in healthcare settings, predicting the LoS of patients in real-time could be a real and useful application for clinicians and nurses to support and optimise their work, save resources for the healthcare systems, and improve the quality of care delivered to patients.

Data availability

Third-party data were used to generate the results reported in this paper. Specifically, the authors used MIMIC-VI 2.2 data available on the PhysioNet repository ([https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2)) and made widely accessible to the international research community through a data use agreement ([https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/view-dua/2.2/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv/view-dua/2.2)) and license ([https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/view-license/2.2/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv/view-license/2.2)).

References

Schiavone, F. & Ferretti, M. The FutureS of healthcare. Futures 134, 102849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102849.

Figueroa, C. A., Harrison, R., Chauhan, A. & Meyer, L. Priorities and challenges for health leadership and workforce management globally: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19 (1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4080-7 (Dec. 2019).

Tran, P. B. et al. Costs of multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 20(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02427-9.

Soley-Bori, M. et al. Impact of multimorbidity on healthcare costs and utilisation: a systematic review of the UK literature. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 71(702), e39–e46. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713897.

World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable diseases, (2023). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=In low-resource settings%2 C health-care costs for NCDs quickly,of people into poverty annually and stifle development. (accessed Apr. 30, 2024).

Nguyen, Q., Wybrow, M., Burstein, F., Taylor, D. & Enticott, J. Understanding the impacts of health information systems on patient flow management: A systematic review across several decades of research. PLoS One 17(9), e0274493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.

Karakusevic, S. Understanding patient flow in hospitals. [Online]. (2016). Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2016/12/patient_flow.pdf

Armony, M. et al. On Patient Flow in Hospitals: A Data-Based Queueing-Science Perspective, Stoch. Syst., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 146–194, Jun. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1287/14-SSY153

Marshall, A., Vasilakis, C. & El-Darzi, E. Length of stay-based patient flow models: recent developments and future directions. Health Care Manag Sci. 8 (3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-005-2012-z (2005).

Bhattacharjee, P. & Ray, P. K. Patient flow modelling and performance analysis of healthcare delivery processes in hospitals: A review and reflections. Comput. Ind. Eng. 78, 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2014.04.016.

Cohen-Stavi, C. J. et al. Guideline deviation and its association with specific chronic diseases among patients with multimorbidity: a cross-sectional cohort study in a care management setting. BMJ Open. 11(1), e040961. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040961.

Reames, B. N., Krell, R. W., Ponto, S. N. & Wong, S. L. Critical Evaluation of Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines, J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 31, no. 20, pp. 2563–2568, Jul. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.46.8371

Guthrie, B., Payne, K., Alderson, P., McMurdo, M. E. T. & Mercer, S. W. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity, BMJ, vol. 345, no. oct04 1, pp. e6341–e6341, Oct. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e6341

Goldbraich, E. et al. Understanding deviations from clinical practice guidelines in adult soft tissue sarcoma. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 216, 280–284 (2015).

Mercuri, M. & Gafni, A. Medical practice variations: what the literature tells us (or does not) about what are warranted and unwarranted variations. J. Eval Clin. Pract. 17(4), 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01689.x.

Atsma, F., Elwyn, G. & Westert, G. Understanding unwarranted variation in clinical practice: a focus on network effects, reflective medicine and learning health systems, Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 271–274, Jun. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa023

Wennberg, J. E. Time to tackle unwarranted variations in practice, BMJ, vol. 342, no. mar17 3, pp. d1513–d1513, Mar. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1513

Harrison, R. et al. Addressing unwarranted clinical variation: A rapid review of current evidence, J. Eval. Clin. Pract., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 53–65, Feb. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12930

Eide, H. P., Barach, P., Søreide, E., Thoresen, C. & Tjomsland, O. Managing unwarranted variation in hospital care – findings from a regional audit in Norway. Res. Heal Serv. Reg. 2(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43999-023-00033-7.

Rathi, R., Vakharia, A. & Shadab, M. Lean six sigma in the healthcare sector: A systematic literature review, Mater. Today Proc., vol. 50, pp. 773–781, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.05.534

Morell-Santandreu, O., Santandreu-Mascarell, C. & Garcia-Sabater, J. J. A Model for the Implementation of Lean Improvements in Healthcare Environments as Applied in a Primary Care Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18(6), 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062876.

Tlapa, D. et al. Feb., Effects of Lean Healthcare on Patient Flow: A Systematic Review, Value Heal., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 260–273, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.11.002

de Koning, H., Verver, J. P. S., van den Heuvel, J., Bisgaard, S. & Does, R. J. M. M. Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare, J. Healthc. Qual., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 4–11, Mar. (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-1474.2006.tb00596.x

Erdogan, T. G. & Tarhan, A. Systematic mapping of process mining studies in healthcare. IEEE Access. 6, 24543–24567. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2831244 (2018).

Batista, E. & Solanas, A. Process Mining in Healthcare: A Systematic Review, in 9th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Jul. 2018, pp. 1–6., Jul. 2018, pp. 1–6. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/IISA.2018.8633608

Rojas, E., Munoz-Gama, J., Sepúlveda, M. & Capurro, D. Process mining in healthcare: A literature review. J. Biomed. Inf. 61, 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2016.04.007 (Jun. 2016).

van der Aalst, W. et al. Process Mining Manifesto,., pp. 169–194. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28108-2_19

van der Aalst, W. Process Mining (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49851-4Berlin.

Goel, S., Bhat, J. M. & Weber, B. End-to-End process extraction in process unaware systems, pp. 162–173. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36285-9_17

van der Aalst, W. M. P. Process-Aware Information Systems: Lessons to Be Learned from Process Mining, pp. 1–26. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-00899-3_1

Van Der Aalst, W. M. P., Leymann, F. & Reisig, W. The role of business processes in service oriented architectures (Editorial). Int. J. Bus. Process. Integr. Manag. 2 (2), 75. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBPIM.2007.015160 (2007).

Munoz-Gama, J. et al. Process mining for healthcare: characteristics and challenges. J. Biomed. Inf. 127, 103994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2022.103994 (Mar. 2022).

van der Aalst, W. M. P. Analyzing ‘Spaghetti Processes,.’ In Process Mining 301–317 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19345-3_12.

Maggi, F. M., Mooij, A. J. & van der Aalst, W. M. P. User-guided discovery of declarative process models, in 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining (CIDM), Apr. pp. 192–199. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/CIDM.2011.5949297

Partington, A., Wynn, M., Suriadi, S., Ouyang, C. & Karnon, J. Process Mining for Clinical Processes, ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1–18, Mar. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2629446

Aria, M., Gnasso, A. & D’Aniello, L. Twenty Years of Random Forest: preliminary results of a systematic literature review, [Online]. (2022). Available: https://hdl.handle.net/11588/895688

Parmar, A., Katariya, R. & Patel, V. A review on random forest: an ensemble classifier, pp. 758–763. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03146-6_86

Biau, G. & Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. TEST 25 (2), 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11749-016-0481-7 (Jun. 2016).

Greasley, A. Using process mapping and business process simulation to support a process-based approach to change in a public sector organisation. Technovation 26 (1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.07.008 (Jan. 2006).

Marriott, R. D. Process Mapping – The Foundation for Effective Quality Improvement, Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 177–181, Jul. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.08.010

Wil & van der Aalst Process Mining: Discovery, Conformance and Enhancement of Business Processes (Springer, 2011).

Rebuge, Á. & Ferreira, D. R. Business process analysis in healthcare environments: A methodology based on process mining. Inf. Syst. 37 (2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2011.01.003 (Apr. 2012).

van der Aalst, W. Process mining: discovering and improving Spaghetti and Lasagna processes, in 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining (CIDM), Apr. pp. 1–7. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/CIDM.2011.6129461

van Eck, M. L., Lu, X., Leemans, S. J. J. & van der Aalst, W. M. P. PM^2: A Process Mining Project Methodology, 2015, pp. 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19069-3_19

Leonetti, S. et al. Process mining discovery starting from process-unaware data: lessons learned from an application in healthcare, in Abstract book DSSR 2024, p. 128. [Online]. Available: https://dssr2024.unina.it/assets/files/Book_of_Abstracts.pdf

Fernandez-Llatas, C., Martinez-Millana, A., Martinez-Romero, A., Benedi, J. M. & Traver, V. Diabetes care related process modelling using Process Mining techniques. Lessons learned in the application of Interactive Pattern Recognition: coping with the Spaghetti Effect, in 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Aug. 2015, pp. 2127–2130., Aug. 2015, pp. 2127–2130. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2015.7318809

N, L. N. and J. V, Trace Clustering Techniques for Process Mining, in Third International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Jan. 2023, pp. 1–6., Jan. 2023, pp. 1–6. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAECT57570.2023.10117842

Buijs, J. C. A. M., van Dongen, B. F. & van der Aalst, W. M. P. On the role of Fitness, Precision, generalization and simplicity in process discovery, pp. 305–322. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33606-5_19

Buijs, J. C. A. M., van Dongen, B. F. & van der Aalst, W. M. P. Quality dimensions in process discovery: the importance of Fitness, Precision, generalization and simplicity. Int. J. Coop. Inf. Syst. 23 (01), 1440001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218843014400012 (Mar. 2014).

Yang, Y., Siau, K., Xie, W. & Sun, Y. Smart Health: Intelligent Healthcare Systems in the Metaverse, Artificial Intelligence, and Data Science Era, J. Organ. End User Comput., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Aug. (2022). https://doi.org/10.4018/JOEUC.308814

Phan, A. C., Phan, T. C. & Trieu, T. N. A systematic approach to healthcare knowledge management systems in the era of big data and artificial intelligence. Appl. Sci. 12 (9), 4455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12094455 (Apr. 2022).

Brzychczy, E. An overview of data mining and process mining applications in underground mining. Inżynieria Min. 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.29227/IM-2019-01-52 (Apr. 2021).

Fernandes, E. C., Fitzgerald, B., Brown, L. & Borsato, M. Machine learning and process mining applied to process optimization: bibliometric and systemic analysis. Procedia Manuf. 38, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.01.012 (2019).

Chen, K., Abtahi, F., Carrero, J. J., Fernandez-Llatas, C. & Seoane, F. Process mining and data mining applications in the domain of chronic diseases: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 144, 102645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102645 (Oct. 2023).

Tello, G., Gianini, G., Mizouni, R. & Damiani, E. Machine Learning-Based framework for Log-Lifting in business process mining applications, pp. 232–249. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26619-6_16

Mehdiyev, N. & Fettke, P. Explainable artificial intelligence for process mining: A general overview and application of a novel local explanation approach for predictive process monitoring, pp. 1–28. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64949-4_1

Blevi, L., Delporte, L., & Robbrecht, J. (2017). Process mining on the loan application process of a Dutch Financial Institute. BPI Challenge, 448, 328-343. https://www.win.tue.nl/bpi/2017/bpi2017_winner_professional.pdf

Palmer, R., Fulop, N. J. & Utley, M. A systematic literature review of operational research methods for modelling patient flow and outcomes within community healthcare and other settings. Heal Syst. 7 (1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41306-017-0024-9 (Jan. 2018).

Stone, K., Zwiggelaar, R., Jones, P., Mac, N. & Parthaláin A systematic review of the prediction of hospital length of stay: towards a unified framework. PLOS Digit. Heal. 1 (4), e0000017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000017 (Apr. 2022).

Scott, A., Shiell, A. & Farnworth, M. G. The value of early discharge: Dispelling some myths, Health Policy (New. York)., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 81–91, Dec. (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(93)90111-2

Clarke, A. Why are we trying to reduce length of stay? Evaluation of the costs and benefits of reducing time in hospital must start from the objectives that govern change., Qual. Saf. Heal. Care, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 172–179, Sep. (1996). https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.5.3.172

Wei, J., He, Z., Ouyang, C. & Moreira, C. MIMICEL: MIMIC-IV event log for emergency department. PhysioNet https://doi.org/10.13026/64aq-jw11 (2022).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x.

Quan, H. et al. Coding Algorithms for Defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 Administrative Data. Med. Care 43(11), 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83.

van Walraven, C., Austin, P. C., Jennings, A., Quan, H. & Forster, A. J. A Modification of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Measures Into a Point System for Hospital Death Using Administrative Data, Med. Care, vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 626–633, Jun. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5

Charlson, M., Szatrowski, T. P., Peterson, J. & Gold, J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47(11), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5.

Wickham, H., Francois, R., Henry, L. & Müller, K. dplyr, A Gramm. Data Manip. [Last accessed 2020 Aug 12] Available from, p. Rproject, 2014., p. Rproject, 2014. (2020).

Wickham, Hadley, et al. "Welcome to the Tidyverse." Journal of open source software 4.43 (2019): 1686.

Liaw, Andy, and Matthew Wiener. "Classification and regression by randomForest." R news 2.3 (2002): 18-22.

Wilkinson, Leland. "ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis by WICKHAM, H." (2011): 678-679. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/

McKinney, W. Pandas: a foundational python library for data analysis and statistics. Python high. Perform. Sci. Comput. 14 (9), 1–9 (2011).

Berti, A., Van Zelst, S. J. & van der Aalst, W. Process mining for python (PM4Py): bridging the gap between process-and data science, arXiv Prepr. arXiv.06169, 2019., 2019. (1905).

Aubert, C. E. et al. Association of patterns of multimorbidity with length of stay. Med. (Baltim). 99(34), e21650. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021650.

Rodrigues, L. P. et al. Association between multimorbidity and hospitalization in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 51(7), https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac155.

Hewitt, J. et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity and its association with outcomes in older emergency general surgical patients: an observational study. BMJ Open. 6(3), e010126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010126.

Wessman, T. et al. The association between length of stay in the emergency department and short-term mortality. Intern. Emerg. Med. 17(1), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-021-02783-z.

Casalino, E. et al. Predictive factors for longer length of stay in an emergency department: a prospective multicentre study evaluating the impact of age, patient’s clinical acuity and complexity, and care pathways. Emerg. Med. J. 31(5), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-202155.

Ye, L. et al. Prolonged length of stay in the emergency department in high-acuity patients at a < scp > C hinese tertiary hospital. Emerg. Med. Australas. 24 (6), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01588.x (Dec. 2012).

Eskandari, M. et al. Evaluation of factors that influenced the length of hospital stay using data mining techniques. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 22(1), 280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-022-02027-w.