Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs), like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), present immense global health challenges, marked by progressive and irreversible neuronal loss. While many studies have reported the neuroprotective potential of various phytochemicals, the neurotherapeutic relevance of alkaloids, like cinchonine remains largely unexplored. This study for the first time investigates cinchonine, a natural Cinchona alkaloid with reported antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and amyloid-inhibitory properties, for its interaction with human transferrin (hTf), a glycoprotein central to iron homeostasis and neuroprotection employing a combination of computational and experimental approaches. UV-Vis spectroscopy revealed significant changes in hTf’s absorbance upon cinchonine binding, confirming stable protein-ligand complex formation, with a binding constant (K) of 0.7 × 105 M− 1. Fluorescence binding assay further validated the formation of a stable protein-ligand complex. Cinchonine binds with hTf with a binding constant (K) of 0.4 × 106 M− 1, signifying the strength of interaction. Molecular docking pinpointed cinchonine’s specific binding site on hTf with a binding affinity of − 6.9 kcal/mol and its interactions with critical residues like Thr392. These findings were reinforced by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and MM-PBSA, which showcased the stability and conformational integrity of the hTf-cinchonine complex over time. Additionally, hydrogen bonding and free energy analyses provided deeper insights into the molecular basis of the protein-ligand complex. All the findings imply the formation of a stable hTf-cinchonine complex. This study underscores cinchonine’s potential as a therapeutic lead, generating hypotheses for future experimental validation of its efficacy in preventing or mitigating NDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) are a class of medical conditions defined by progressive degradation of the structure and function of the central or peripheral nervous systems1,2,3,4,5. They pose multiple substantial difficulties to global health systems and are a leading cause of disability and death worldwide3The importance of understanding neurodegenerative disorders grows as their prevalence increases in aging populations. They have a deleterious impact on patients and their caregivers (hospital staff, family, friends, and society)6. Some of the challenges that every medical professional faces when attempting to treat NDs include the irreversibility of neuronal loss7, complexity due to the involvement of multiple interacting mechanisms8, the limited ability of drugs to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to reach the affected site of damage7, and diagnosis at a later stage when most treatment options become ineffective. While diagnosing a patient suffering from NDs, it has been observed that these diseases either occur or become severe due to various molecular and cellular factors, which include oxidative stress arising due to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) thereby causing cellular damage9, chronic neuroinflammation10, protein aggregation and misfolding (which also serves as a biomarker in most of the diseases either being found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or post-mortem brain tissues of died person), mitochondrial dysfunction creating an imbalance in energy metabolism5,11,12, and dysregulation of metal homeostasis contributing to various metabolic processes13.

Phytochemicals are bioactive compounds produced by plants, often as part of their defense mechanisms against environmental pathogenic microbes (such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) and other environmental stressors14,15. Polyphenols, alkaloids, terpenes, and organosulfur compounds are among the phytochemical families that have received the most attention due to their therapeutic properties16. A variety of phytochemicals observed from plant sources provides a rich source of therapeutic agents to investigate the modulation of NDs due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-aggregatory17, neuroprotective, mitochondrial function enhancers18,19, and metal chelation properties20. The most common ND is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which worsens with age and is a primary cause of death in elderly populations4. Late-stage Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by substantial cognitive decline, memory impairment and loss, and behavioral changes that occur in practically every large community of affected individuals21. More than 70% of dementia cases are caused by AD, with Parkinson’s disease (PD), Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and other conditions accounting for the remainder4,22,23. Although Lecanemab came into the spotlight in the year 202222 and Aducanumab in 2007, our search for a perfect, effective medicine continues due to limitations and negative effects. In the ongoing search for a better alternative that has improved disease-modifying properties and little to no drawbacks, many researchers came across Cinchonine (a phytochemical belonging to the alkaloid family), which is a common product derived from the bark of Cinchona trees24. Cinchona, being an alkaloid, resembles structural quinine, a prominent antimalarial chemical used for decades25. Cinchona is one of four primary alkaloid phytochemicals derived from Cinchona trees, the other three being quinine, quinidine, and cinchonidine26. With a molecular weight of less than 500 kDa24, cinchonine offers features that target the inhibition of NDs24. Cinchona alkaloids have pharmacological activities ranging from antimalarial27 to anticancer28, and many others29,30. Cinchonine has potential as a treatment for AD due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, acetylcholinesterase inhibitory, neuroprotective, and Amyloid-β inhibitory properties24. Justifying the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) features, it easily crosses the blood-brain barrier to reach the damaged organ and exhibits multi-target activity31. As cinchonine is obtained from a natural source, it is predicted to have much lesser-known side effects. It also displays similarities to other recognized compounds, such as quinine, which is another member of its family and a well-studied chemical for a better understanding of its druglike features, including pharmacokinetics and potential interactions24. The pharmacological significance of cinchonine aligns with a broader trend of exploring phytochemicals and traditional medicines for neuroprotection. For instance, a study reviewed multiple conventional medicinal plants and experimental models used in AD research32. Another study by Zhang et al. (2026) carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis, showing the neuroprotective efficacy of Boswellia extract in experimental models of AD and related disorders33. These studies highlight the therapeutic potential of natural compounds targeting oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and amyloidogenic cascades.

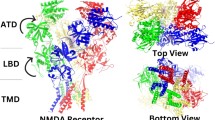

hTf has an important role in iron metabolism and has emerged as a molecule of interest due to its ability to modulate neurodegenerative processes34. hTf is a glycoprotein primarily synthesized in the liver, having a molecular weight of 80 kDa (approximately). hTf belongs to the transferrin family of iron-binding proteins and is essential for iron transport throughout the body35. It consists of two homologous lobes, each capable of binding a single ferric iron (Fe3+) ion with great affinity35. hTf performs multiple important roles, including iron transport, iron sequestration, cell proliferation and differentiation, and neuroprotection against iron-induced oxidative stress, highlighting its significance36,37,38,39. Structurally, hTf consists of two homologous lobes, the N-lobe and the C-lobe, connected by a short peptide linker (Fig. 1). Each lobe is further divided into two domains that form a deep interdomain cleft responsible for binding a single ferric ion (Fe3+) in coordination with carbonate anions. These binding clefts undergo conformational opening and closing during iron loading and release, processes essential for transferrin receptor recognition and cellular iron uptake. Several small-molecule modulators of hTf have been investigated for their potential therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, thymoquinone, a phytochemical derived from Nigella sativa, was shown to bind hTf and modulate iron metabolism in AD models. Similarly, caffeic acid and rivastigmine tartrate exhibited hTf-binding activity and contributed to reduced oxidative and amyloidogenic stress in preclinical assays. These findings highlight hTf as a promising therapeutic target and support the rationale for evaluating cinchonine’s interaction with this protein.

Overall structure and dual metal-binding sites of human transferrin (hTf). The diferric hTf structure displays its two homologous lobes: the N-lobe (lavender) and C-lobe (tan), each coordinating one ferric ion (Fe³⁺, orange spheres). The Fe³⁺ Binding Site 1 in the N-lobe (red) and Fe³⁺ Binding Site 2 in the C-lobe (purple) are shown with their coordinating residues. Associated hydrogencarbonate cofactors are depicted at Site 1 (green) and Site 2 (cyan), illustrating the bidentate coordination that stabilizes Fe³⁺ binding in both lobes. This structural representation highlights the bilobal architecture of hTf and its dual metal-binding centers essential for iron transport and receptor interaction. The figure was generated through PyMOL using the hTf structural coordinates from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3V83).

The iron-sequestering action of hTf might decrease Amyloid-β aggregation, which is another feature of iron imbalance40. hTf’s disease-modifying capabilities make it an intriguing target for potential drugs against AD and other NDs. Drug-protein interactions play an important role in pharmacology, regulating drug effectiveness, distribution, and metabolism. Understanding these interactions is critical for therapeutic development and optimization, particularly in the context of AD. When cinchonine binds to hTf, it may induce structural alterations that may affect its iron-binding capacity. This modification of iron homeostasis has important ramifications. Despite its significance, research on the interaction of cinchonine and hTf is largely unexplored and thus our study is the first of its kind to explore this binding mechanism, employing a blend of computational and experimental approaches.

Materials and methods

Material

We purchased human transferrin (hTf) and cinchonine from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). hTf (catalog no. T8158), Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used in this study. SRL provided the additional chemicals needed to prepare the buffer. All the buffers were made using double-distilled and de-ionized water using a Milli-Q® UF-Plus purification system. hTf stock solution was made in a sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM), pH 7.4. To create a ligand stock solution, ethanol was used to solubilize cinchonine powder. Prior to use, each solution was stored at 4 °C in the dark. The stated spectra here are spectra that have been subtracted. Appropriate blanks were employed as controls and run under identical conditions. Before being used, each solution was fully degassed. All the spectroscopic assays were performed in triplicates.

UV–vis spectroscopy

Protein samples without a ligand (apo-protein) and protein samples with ligand concentrations that increased gradually were used in the spectrophotometric measurement of absorbance spectra. The Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer, which had a 1 cm path length, was utilized. In this experiment, 4 µM of the protein was used, and the protein solution was gradually exposed to increasing ligand concentrations. From 1 to 9 µM, the ligand concentration was steadily increased. A phosphate buffer with a pH of 7.4 was used to make baseline corrections for measurements between 240 and 340 nm in wavelength. The Modified Beer-Lambert’s equation was utilised to get the binding constant as mentioned in the equation below (Eq. 1)

A0 and A depict absorbance of free hTf and in the presence of cinchonine, respectively.

\(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{h}\text{T}\text{f}}\)= molar absorptivity (extinction coefficient) of hTf.

\(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{B}}\)= molar absorptivity (extinction coefficient) of the ligand.

\(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{h}\text{T}\text{f}}\)/εBK = ratio of molar absorptivity of the protein to that of the ligand.

C is the concentration of cinchonine.

Fluorescence quenching assay

Shimadzu Spectrophotometer (RF6000) was used to perform fluorescence quenching studies at 25 °C. The powdered ligand was dissolved in ethanol to create a stock of 1 mM. Protein emission spectra were obtained using stimulated protein with medium response at 280 nm. The 300–400 nm range was used to measure the emission spectrum. 0.5 µL of the ligand’s 1 mM stock was used to titrate the protein. At each titration, 0.5 µL of the ligand was introduced one at a time. All the fluorescence spectra were corrected for inner filter effects as previously published literature. The final ethanol concentration was kept below 1% (v/v) in all titrations to prevent any influence on hTf structure or aggregation. Baseline spectra of buffer and ethanol controls were subtracted to eliminate background interference. Finally, Stern-Volmer constant (Ksv)and binding constant (K) was obtained using the Stern-Volmer (Eq. 2) and modified Stern Volmer equation (Eq. 3), respectively, as per earlier published literatures 41.

Highest fluorescence intensity of only hTf is F0 whilst F depicts fluorescence intensity in the existence of cinchonine, Ksv depicts the Stern-Volmer constant and the concentration of cinchonine is depicted by C.

Highest fluorescence intensity of only hTf is F0 whilst F depicts fluorescence intensity in the existence of Cinchonine, K depicts the binding constant, n depicts the number of binding sites, and the concentration of cinchonine is depicted by C.

Molecular docking

The crystal structure of hTf with a resolution of 2.1 angstroms was acquired from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3V83)42. Among various hTf structures available in the PDB, we selected the diferric hTf structure with a 2.1 Å resolution due to its high completeness, low R-factor, and accurate representation of the functional iron-bound state. This structure offers well-defined domain orientations and a complete set of binding site residues, making it suitable for reliable docking simulations. Removal of non-protein atoms and crystal waters was conducted in MGL AutoDock Tools43. Protonate3D44 was utilized for optimizing hydrogen bonds at a physiological pH of 7.3, with the help of the H + + Server45 for protein setup. The 3D structure of cinchonine was obtained from the PubChem database (ID: 90454)46. The structure of cinchonine was subjected to geometry optimization using ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0 to obtain the lowest-energy conformer before docking. Molecular docking was executed employing the standard protocol of InstaDock software47. InstaDock is a QuickVina-W GUI based on a modified AutoDock Vina search strategy48. The search space was set to − 52.428, 17.896, and − 30.152, with a size of 70, 80, and 70 in the X, Y, and Z, respectively. Parameters such as exhaustiveness (set to 50), energy cutoff (1 kcal/mol), and RMSD cutoff (2Å) were specified. To evaluate the reliability of the docking protocol, a retrospective redocking was conducted using 8R6, the co-crystallized ligand of hTf (PDB ID: 5Y6K). The redocked pose closely matched the experimentally determined structure, exhibiting an RMSD of 0.218 Å (Supplementary Figure S1). This strong concordance validates the protocol’s accuracy in reproducing ligand orientations within the hTf binding pocket. Following docking, multiple poses were analyzed and clustered based on RMSD criteria (cutoff 2.0 Å). The representative pose from the most populated cluster, exhibiting both favorable binding energy and consistent interaction geometry, was chosen as the initial structure for MD simulations. Assessment of the ligand’s druggability, cinchonine, involved calculating ligand descriptors using SwissADME49. Cinchonine was found to possess 22 heavy atoms, 3 hydrogen bond acceptors, 1 hydrogen bond donor, solubility in water of − 3.49, and a molecular weight of 294.39 g/mol. It met al.l criteria for the Lipinski rule of five and does not contain any Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) pattern.

MD simulations

The highest-scoring pose of the hTf-cinchonine complex obtained from the docking study was selected for the all-atom MD simulation to evaluate their dynamics. The ligand was parametrized using CGenFF server50, and the CHARMM36-JUL2022 force field51 was employed for the simulations. The protein and protein-ligand complex were solvated in a 10 Å box of TIP3P solvent52. Appropriate numbers of required sodium/chloride ions were supplied for the electroneutrality of the systems. The prepared systems were first energy-minimized using the steepest descent algorithm until the maximum force was below 1,000 kJ/mol/nm to remove steric clashes. This was followed by two equilibration steps: a 100 ps NVT equilibration at 300 K using a V-rescale thermostat, and a 100 ps NPT equilibration at 1 bar employing the Parrinello–Rahman barostat. Heavy atoms of the protein–ligand complex were restrained during equilibration to allow solvent relaxation. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, with a 1.2 nm cutoff for short-range interactions. Bond constraints were maintained via the LINCS algorithm, and a 2 fs integration timestep was used. The simulation protocol was executed in the GROMACS (version 2022.4) suite with multiple gmx modules. GPU acceleration was utilized to enhance computational efficiency during the 200 ns MD simulations.

MM-PBSA analysis

To quantitatively evaluate the binding affinities of the protein–ligand complexes, the Molecular Mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) method was applied. Calculations were performed using the gmx_MMPBSA tool on representative trajectory frames obtained from MD simulations executed with GROMACS (version 2022.4). Specifically, 10-ns segments were extracted from the 200-ns production trajectories, and binding energy estimations were computed at 0.1-ns intervals. The MM-PBSA approach decomposes the total binding free energy into key energetic components, including van der Waals, electrostatic, and internal energy contributions, as well as polar solvation (derived from the Poisson–Boltzmann equation) and non-polar solvation terms (estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area). The overall binding free energy (ΔGbinding) was determined using the equation:

where complex represents the total energy of the bound system, receptor is the energy of the unbound protein, and ligand corresponds to the energy of the free ligand.

Results and discussions

UV–vis spectroscopy

Upon the binding of the ligand to the protein, a complex is formed, which can be quantified using UV-vis spectroscopy. Changes in the UV-vis spectra, such as variations in absorbance levels and shifts in the peak positions (λmax), indicate the extent of interaction between the ligand and the protein. Therefore, UV-vis spectroscopy is a commonly employed method for characterizing protein-ligand complexes. We performed a titration of hTf using various concentrations of cinchonine (0–0.9 µM) and observed a hyperchromic effect in the UV-visible spectra of hTf. There was no shift in the peak observed upon titration with cinchonine, with λmax being observed at around 279 nm for the native protein; only a hyperchromic effect was evident, with no shift in the peak. The data was analyzed using the Modified Beer-Lambert equation, and a double reciprocal plot of 1/(A − A0) versus 1/C was generated. The binding constant (K) for the hTf-cinchonine complex was determined from the ratio of the intercept to the slope of this plot, as shown in Fig. 2. The binding constant (K) for the hTf-cinchonine complex was calculated to be 0.7 × 105 M− 1, indicating that cinchonine forms a stable complex with hTf and exhibits a strong binding affinity and is in line with the binding constant reported for other protein-ligand complexes53.

Fluorescence binding assay

Cinchonine was used as a ligand in the fluorescence binding experiments with hTf. hTf has demonstrated efficient binding with a number of different ligands. A popular method for figuring out the binding affinities of protein-ligand complexes is intrinsic fluorescence54,55. Intrinsic fluorophores, mainly tryptophan in proteins, bind to its target, and the fluorescence signal can change in intensity or wavelength. This change occurs due to alterations in the fluorophore’s environment, which affect its fluorescence properties. Protein fluorescence intensity changes were tracked in relation to ligand concentration (Fig. 3A). Ksv (Stern-Volmer constant) was quantified using the Stern-Volmer equation and found to be 3.19 × 105 M− 1 (Fig. 3B). Using the modified Stern Volmer equation, the binding constant (K), as shown in Fig. 3C, was determined to be 0.14 × 106 M− 1. The binding constant (K) obtained aligns well with values reported for other protein-ligand complexes56, indicating that cinchonine interacts with hTf to form a stable and robust complex. The obtained K from fluorescence quenching experiment varies from that obtained through UV-visible spectroscopic studies, and it is a commonly observed phenomenon that has been previously reported53,57.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking is a pivotal tool for investigating protein-ligand interactions, providing valuable insights into their binding mechanisms58. Here, structure-based docking was employed to examine the binding prototype of cinchonine within the hTf binding site. Cinchonine showed a binding affinity of − 6.9 kcal/mol with the binding site of hTf. It showed a ligand efficiency of 0.31 kcal/mol/non-H atom with the hTf structure. The redocking analysis of a co-crystallized ligand, 8R6, with hTf showed a binding affinity of − 5.2 kcal/mol with a ligand efficiency of 0.1529 kcal/mol/non-H atom. Cinchonine showed better affinity towards hTf than 8R6 and other previously reported small-molecule binders59,60. The binding affinity and ligand efficiency assessment supported the stability of the hTf-cinchonine docked complex. Cinchonine demonstrated significant interactions with key residues of hTf (Fig. 4). Figure 4A elucidates the detailed binding prototype of cinchonine with hTf, highlighting multiple binding residues involved within the protein. Cinchonine forms 1 hydrogen bond with Thr392, along with several other close interactions (Fig. 4B). The preferential interaction of cinchonine showed its binding into the deep cavity of the hTf binding pocket (Fig. 4C). The 2-D interaction diagram showed the residues contributing to the hTf-cinchonine complex formation, which emphasizes the potential binding of cinchonine with hTf (Fig. 4D). The plot showed that cinchonine interacted with multiple binding site residues in hTf through various interactions, such as conventional hydrogen bonding, Pi-Anion, Alkyl, and van der Waals interactions. The binding observed in molecular docking indicates the stability of the hTf-cinchonine complex. Overall, the docking result suggests that cinchonine can be a promising binding partner of hTf for its therapeutic modulation.

MD simulations

MD simulations are crucial for assessing the dynamic stability of the docked complex over an extended period61,62. In recent times, MD simulations and related computational approaches have been increasingly utilised to investigate conformational behaviour and pathogenic alterations in disease-associated proteins63. Similar computational approaches, including dispersion-corrected DFT and MD-based umbrella sampling, have been reported for studying inclusion complexes such as chrysin–cyclodextrin64 The binding of small molecules to proteins induces notable perturbations in the global structure of the macromolecule65. MD simulations offer a powerful means to scrutinize these phenomena at an atomistic scale. Root mean squared deviation (RMSD) serves as a useful parameter to examine residual fluctuations in proteins. In this study, we examined the RMSD for both the hTf and the hTf-cinchonine complex to compare their dynamics (Fig. 5A). The RMSD of cinchonine was computed to analyze its movement during the 200 ns production runs. The plot reveals that the hTf-Cinchonine undergoes visible stability during the 200 ns of the MD run. This indicates that the tertiary structure attains stability after 50 ns of the production runs. The RMSF plot of the simulated trajectory also showed a similar pattern of distribution in the cases (Fig. 5B). The RMSF pattern of the complex system suggests lower residual fluctuations compared to the free system. The observed dynamics provide valuable insights into the conformational changes and stability of the hTf-cinchonine complex during the MD simulations.

The radius of gyration (Rg) serves as a crucial metric for assessing the tertiary structure compactness of proteins66. Rg provides valuable insights into the folding behavior and overall dimensions of proteins. The Rg values for the apo and cinchonine bound hTf were analyzed from the simulated trajectories. For the apo hTf and the hTf-cinchonine complex, the Rg values were distributed between 2.95 nm and 3.05 nm (Fig. 5C). The Rg plots indicate that cinchonine binding does not induce any structural switching in hTf and maintains conformational integrity throughout the simulation. Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) is another critical attribute directly linked to protein folding and stability67. SASA monitoring during the 200 ns MD simulations provides valuable insights into the conformational dynamics of hTf. The SASA results indicate a rational equilibration with no significant changes in hTf before and after cinchonine binding (Fig. 5D). The combined Rg and SASA analyses underscore the stability of hTf throughout the MD simulation period.

Hydrogen bond dynamics

Hydrogen bonding stands as one of the pivotal specific interactions in biological recognition processes that plays a crucial role in molecular interactions68. In this study, hydrogen bond analysis was conducted to evaluate the time-evolution dynamics of hydrogen bonds formed during the simulation. Figure 6A illustrates the intramolecular hydrogen bonds formed within the hTf structure. The results showed that the hydrogen bonds formed within hTf were stable and maintained within the protein structure during the MD simulations. Figure 6B depicts intermolecular interactions formed between cinchonine with hTf. The plot demonstrates 1–3 hydrogen bond interactions between cinchonine and hTf. These hydrogen bond dynamics shed light on the molecular interactions that contribute to the stability and recognition processes within the hTf-cinchonine complex during the MD simulations. In summary, the hydrogen bond analyses emphasize the persistent nature of critical interactions within the protein structure and highlight the intermolecular hydrogen bonds formed by cinchonine. Overall, the analysis provides valuable insights into the dynamics of the hTf-cinchonine complex.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) stands as a potent method utilized in scrutinizing the structural dynamics of proteins and their complexes with ligands69. In this investigation, PCA scrutinized the trajectory data derived from simulations of both hTf and hTf-cinchonine complexes (Fig. 7). The findings reveal that the hTf-cinchonine complex predominantly occupies a phase space akin to that of free hTf (Fig. 7A). Specifically, PCA describes that cinchonine binding to hTf induces a noticeable decrease in the flexibility of the protein structure along EV2 (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the observed reduction in the conformational flexibility of hTf upon cinchonine binding indicates restricted mobility of residues primarily located at the inter-lobal hinge regions responsible for iron release and receptor recognition. Such a decrease in atomic fluctuations implies that cinchonine stabilizes these dynamic regions, potentially enhancing the structural rigidity necessary for maintaining functional integrity. Functionally, this stabilization could help preserve hTf’s iron-binding and neuroprotective roles, which are often compromised under oxidative or amyloidogenic stress conditions associated with neurodegeneration.

Free energy landscape analysis

Free energy landscape (FEL) analysis is a robust technique utilized for exploring the conformational space of proteins and their complexes in MD simulations70. It aids in discerning the kinetic and thermodynamic states of these biomolecules. In this investigation, FELs were employed to evaluate the folding dynamics of hTf. The graphical representations of FELs offer a visual depiction of the protein’s conformational landscape and its energetically favorable states (Fig. 8). Notably, regions shaded in dark blue denote heightened stability, indicative of structures that are thermodynamically favored. To further quantify conformational stability, the free energy difference (ΔG) between the two dominant minima on the landscape was calculated. For apo hTf, ΔG between the major basins was approximately 2.4 kcal/mol, whereas the hTf-cinchonine complex exhibited a narrower separation of 1.1 kcal/mol between basins. This lower energy difference suggests that cinchonine binding stabilizes the protein in a more energetically favorable and homogeneous conformational state, corroborating the PCA findings of reduced flexibility and enhanced compactness. The FEL analysis depicted the landscapes of both hTf and the hTf-cinchonine complex projected on PC1 and PC2. These analyses revealed that the stability of the hTf-cinchonine complex closely resembles that of free hTf (Fig. 8A-B). In summary, FEL analysis provided a detailed understanding of the protein’s conformational dynamics that aligns with the insights gained from PCA and corroborates the increased stability observed in the hTf-cinchonine complex.

MM-PBSA analysis

To assess the binding strength of the selected ligands with hTf, MM-PBSA calculations were performed on snapshots extracted from the equilibrated MD trajectories. This analysis enabled quantitative estimation of the binding free energies by separating the total ΔGbinding into major energetic contributions, including gas-phase interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics) and solvation effects (polar and non-polar components). Among the tested compounds, cinchonine exhibited the most favorable binding characteristics, with a binding free energy of − 14.82 ± 3.18 kJ/mol. The negative ΔGbinding value indicates energetically favorable interactions and supports the formation of a stable hTf–cinchonine complex. Collectively, these findings suggest that cinchonine may serve as a promising modulator of hTf activity.

Conclusions

The present study uses fluorescence quenching, UV-vis spectroscopy, molecular docking, and MD simulations to describe the interaction between hTf and cinchonine. UV-vis spectroscopy suggested the formation of the stable hTf-cinchonine complex. According to fluorescence assessments, hTf-cinchonine’s binding constant was 0.14 × 106 M− 1, suggesting that cinchonine has a very high affinity for hTf, i.e., cinchonine binds to hTf, forming a stable complex. Additionally, molecular docking was used to gain insight into cinchonine’s method of interaction with hTf. The crucial residues for this interaction were identified via molecular docking. Cinchonine interacts closely with Thr392 in several ways, including forming one hydrogen bond. Our fluorescence experiments were further corroborated by molecular docking, which confirmed that hydrogen bonding drives the hTf-cinchonine interaction. Additionally, MD simulation studies were conducted to validate our observations, and MD studies suggested minimal structural alterations in hTf upon the binding of cinchonine and demonstrated that cinchonine binds to hTf, forming a stable complex and shedding light on the binding process at the atomistic level. Numerous studies have shown that alkaloids have a preventive effect against NDs. Our results suggest that cinchonine interacts stably with hTf, indicating potential pharmacological relevance; however, further experimental validation is required. Together, our findings suggest that cinchonine interacts stably with hTf, implicative of the potential pharmacological significance in the context of NDs pathology. While the current findings provide in vitro and in silico insights into the interaction of cinchonine with hTf, the absence of cellular or in vivo validation represents a limitation. Future studies employing biological models will be essential to validate these findings thereby affirming the translational relevance and neuroprotective potential of cinchonine in NDs.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the supplementary material.

References

Yacoubian, T. A. In Drug Discovery Approaches for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders (ed Adeboye Adejare), 1–16 (Academic, 2017).

Yang, J., Li, H. & Zhao, Y. Dessert or poison? The roles of glycosylation in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s Disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ChemBioChem 24, e202300017. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202300017 (2023).

Pathak, N. et al. Neurodegenerative disorders of Alzheimer, Parkinsonism, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis: an early diagnostic approach for precision treatment. Metab. Brain Dis. 37, 67–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-021-00800-w (2022).

Iram, F. et al. Navigating the maze of alzheimer’s disease by exploring BACE1: Discovery, current scenario, and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 98, 102342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102342 (2024).

Khan, T. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction: pathophysiology and Mitochondria-Targeted drug delivery approaches. Pharmaceutics 14, 2657 (2022).

Mossa, A., Mayahara, M., Emezue, C. & Paun, O. The impact of rapidly progressing neurodegenerative disorders on caregivers: an integrative literature review. J. Hospice Palliat. Nurs. 26, E62–E73. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000997 (2024).

Lamptey, R. N. L. et al. A review of the common neurodegenerative disorders: current therapeutic approaches and the potential role of nanotherapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031851 (2022).

Guo, T. et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegeneration. 15, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-020-00391-7 (2020).

Sweeney, M. D., Sagare, A. P. & Zlokovic, B. V. Blood–brain barrier breakdown in alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Reviews Neurol. 14, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188 (2018).

Koronyo-Hamaoui, M., Gaire, B. P., Frautschy, S. A. & Alvarez, J. I. Editorial: role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Immunol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.958487 (2022).

Ashleigh, T., Swerdlow, R. H. & Beal, M. F. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 19, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12683 (2023).

Ahmad, S., Gupta, D., Ahmed, T. & Islam, A. Designing of new tetrahydro-β-carboline-based ABCG2 inhibitors using 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and DFT tools. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. 41, 14016–14027. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2023.2176361 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Biometal dyshomeostasis and toxic metal accumulations in the development of alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00339 (2017).

Desmedt, W., Mangelinckx, S., Kyndt, T. & Vanholme, B. A phytochemical perspective on plant defense against nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.602079 (2020).

Ahmad, S., Hassan, M. I., Gupta, D., Dwivedi, N. & Islam, A. Design and evaluation of pyrimidine derivatives as potent inhibitors of ABCG2, a breast cancer resistance protein. 3 Biotech 12, 182, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-022-03231-1

Tripathi, S. et al. Transcription factor repertoire in Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) through analytics of transcriptomic resources: insights into regulation of development and withanolide metabolism. Sci. Rep. 7, 16649. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14657-6 (2017).

Sharifi-Rad, J. et al. Multi-Target mechanisms of phytochemicals in alzheimer’s disease: effects on oxidative Stress, neuroinflammation and protein aggregation. J. Personalized Med. 12, 1515 (2022).

Naoi, M., Wu, Y., Shamoto-Nagai, M. & Maruyama, W. Mitochondria in neuroprotection by phytochemicals: bioactive polyphenols modulate mitochondrial apoptosis System, function and structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2451 (2019).

Velmurugan, B. K., Rathinasamy, B., Lohanathan, B. P., Thiyagarajan, V. & Weng, C. F. Neuroprotective role of phytochemicals. Molecules 23, 2485 (2018).

Adusei, S., Otchere, J. K., Oteng, P., Mensah, R. Q. & Tei-Mensah, E. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant and metal chelating capacity of tetrapleura tetraptera. Heliyon 5, e02762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02762 (2019).

Knopman, D. S. et al. Alzheimer disease. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers. 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00269-y (2021).

Khan, T. et al. Recent advancement in therapeutic strategies for alzheimer’s disease: insights from clinical trials. Ageing Res. Rev. 92, 102113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102113 (2023).

Khan, T. et al. Understanding the modulation of α-Synuclein fibrillation by N-Acetyl aspartate: A brain metabolite. ACS Omega. 9, 12262–12271. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c00595 (2024).

Parveen, S., Maurya, N., Meena, A., Luqman, S. & Cinchonine A versatile Pharmacological agent derived from natural Cinchona alkaloids. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 24, 343–363. https://doi.org/10.2174/0115680266270796231109171808 (2024).

Tisnerat, C., Dassonville-Klimpt, A., Gosselet, F. & Sonnet, P. Antimalarial drug discovery: from quinine to the most recent promising clinical drug candidates. Curr. Med. Chem. 29, 3326–3365. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867328666210803152419 (2022).

Aslam, S., Jabeen, T., Ahmad, M. & AL-Huqail, A. A. In Essentials of Medicinal and Aromatic Crops (eds Muhammad Zia-Ul-Haq, 221–248 (Springer International Publishing, 2023). Arwa Abdulkreem Al-Huqail, Muhammad Riaz, & Umar Farooq Gohar)

Lee, S. Y. et al. Hydrocinchonine, cinchonine, and Quinidine potentiate paclitaxel-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis via multidrug resistance reversal in MES‐SA/DX5 uterine sarcoma cells. Environ. Toxicol. 26, 424–431 (2011).

El-Mesery, M., Seher, A., El‐Shafey, M., El‐Dosoky, M. & Badria, F. A. Repurposing of Quinoline alkaloids identifies their ability to enhance doxorubicin‐induced sub‐G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cervical and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biotechnol. Appl. Chem. 68, 832–840 (2021).

Parveen, S., Maurya, N., Meena, A., Luqman, S. & Cinchonine A versatile Pharmacological agent derived from natural Cinchona alkaloids. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 24, 343–363 (2024).

Jo, Y. J. et al. Cinchonine inhibits osteoclast differentiation by regulating TAK1 and AKT, and promotes osteogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 236, 1854–1865 (2021).

Ramić, A. et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation and machine learning prediction model for fluorinated Cinchona Alkaloid-Based derivatives as cholinesterase inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 15, 1214 (2022).

Kombo, H., Kumar, S. & Singh, G. Traditional medicines and experimental analysis methods for alzheimer’s disease. Tradit Med. Res. 7, 43 (2022).

Zhang, M., Liao, Y. & Liang, S. Neuroprotective effects of Boswellia extract in animal models of ischemic stroke, parkinson’s disease, and alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tradit Med. Res. 11, 13 (2026).

Xue, B. et al. Investigating binding mechanism of thymoquinone to human transferrin, targeting alzheimer’s disease therapy. J. Cell. Biochem. 123, 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.30299 (2022).

Kawabata, H. Transferrin and transferrin receptors update. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 133, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.037 (2019).

Cheli, V. T. et al. Transferrin receptor is necessary for proper oligodendrocyte iron homeostasis and development. J. Neurosci. 43, 3614–3629. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1383-22.2023 (2023).

Rodríguez-García, C. et al. Transferrin-mediated iron sequestration suggests a novel therapeutic strategy for controlling Nosema disease in the honey bee, apis mellifera. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009270. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009270 (2021).

Macedo, M. F. et al. Transferrin is required for early T-cell differentiation. Immunology 112, 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01915.x (2004).

Youale, J. et al. Neuroprotective effects of transferrin in experimental glaucoma models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 12753 (2022).

Hou, T. et al. Photooxidative Inhibition and decomposition of β-amyloid in alzheimer’s by nano-assemblies of transferrin and indocyanine green. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 241, 124432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124432 (2023).

Shamsi, A. et al. Comprehensive insight into the molecular interaction of Rutin with human transferrin: implication of natural compounds in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 126643 (2023).

Noinaj, N. et al. Structural basis for iron piracy by pathogenic neisseria. Nature 483, 53–58 (2012).

Huey, R., Morris, G. M. & Forli, S. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock Vina with autodocktools: a tutorial. Scripps Res. Inst. Mol. Graphics Lab. 10550, 1000 (2012).

Labute, P. & Protonate 3D: assignment of ionization States and hydrogen coordinates to macromolecular structures. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 75, 187–205 (2009).

Gordon, J. C. et al. H++: a server for estimating p K as and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W368–W371 (2005).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1202–D1213 (2016).

Mohammad, T., Mathur, Y., Hassan, M. I. & InstaDock A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Brief. Bioinform. 22, bbaa279 (2021).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717 (2017).

Zhu, S. Validation of the generalized force fields GAFF, CGenFF, OPLS-AA, and PRODRGFF by testing against experimental osmotic coefficient data for small drug-like molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 4239–4247 (2019).

Huang, J. & MacKerell, A. D. Jr CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2135–2145 (2013).

Mark, P. & Nilsson, L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A. 105, 9954–9960 (2001).

Qais, F. A., Alam, M. M., Naseem, I. & Ahmad, I. Understanding the mechanism of non-enzymatic glycation Inhibition by cinnamic acid: an in vitro interaction and molecular modelling study. RSC Adv. 6, 65322–65337 (2016).

Soares, S., Mateus, N. & De Freitas, V. Interaction of different polyphenols with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and human salivary α-amylase (HSA) by fluorescence quenching. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 6726–6735 (2007).

Klajnert, B., Stanisławska, L., Bryszewska, M. & Pałecz, B. Interactions between PAMAM dendrimers and bovine serum albumin. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 1648, 115–126 (2003).

Rehman, M. T., Shamsi, H. & Khan, A. U. Insight into the binding mechanism of Imipenem to human serum albumin by spectroscopic and computational approaches. Mol. Pharm. 11, 1785–1797 (2014).

Alam, M. M. et al. Multi-spectroscopic and molecular modelling approach to investigate the interaction of riboflavin with human serum albumin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. 36, 795–809 (2018).

Naqvi, A. A., Mohammad, T., Hasan, G. M. & Hassan, M. I. Advancements in Docking and molecular dynamics simulations towards ligand-receptor interactions and structure-function relationships. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 18, 1755–1768 (2018).

Shamsi, A. et al. Unraveling binding mechanism of alzheimer’s drug Rivastigmine tartrate with human transferrin: molecular Docking and multi-spectroscopic approach towards neurodegenerative diseases. Biomolecules 9, 495 (2019).

Shamsi, A., Shahwan, M., Das Gupta, D., Abdullah, K. & Khan, M. S. Implication of caffeic acid for the prevention and treatment of alzheimer’s disease: Understanding the binding with human transferrin using in Silico and in vitro approaches. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 2176–2185 (2024).

Shukla, R. & Tripathi, T. Molecular dynamics simulation of protein and protein–ligand complexes. Computer-aided Drug Design, 133–161 (2020).

Kamaraj, B., Rajendran, V., Sethumadhavan, R. & Purohit, R. In-silico screening of cancer associated mutation on PLK1 protein and its structural consequences. J. Mol. Model. 19, 5587–5599 (2013).

Kamaraj, B. & Purohit, R. Mutational analysis on membrane associated transporter protein (MATP) and their structural consequences in oculocutaeous albinism type 4 (OCA4)—a molecular dynamics approach. J. Cell. Biochem. 117, 2608–2619 (2016).

Kumar, P., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Dispersion-corrected DFT calculations and umbrella sampling simulations to investigate stability of Chrysin-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Carbohydr. Polym. 319, 121162 (2023).

Mohammad, T. et al. Virtual screening approach to identify high-affinity inhibitors of serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 among bioactive natural products: combined molecular Docking and simulation studies. Molecules 25, 823 (2020).

Lobanov, M. Y., Bogatyreva, N. & Galzitskaya, O. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol. Biol. 42, 623–628 (2008).

Durham, E., Dorr, B., Woetzel, N., Staritzbichler, R. & Meiler, J. Solvent accessible surface area approximations for rapid and accurate protein structure prediction. J. Mol. Model. 15, 1093–1108 (2009).

Bitencourt-Ferreira, G. & Veit-Acosta, M. & de Azevedo, W. F. Hydrogen bonds in protein-ligand complexes. Docking Screens Drug Discovery, 93–107 (2019).

Tharwat, A. Principal component analysis-a tutorial. Int. J. Appl. Pattern Recognit. 3, 197–240 (2016).

Papaleo, E., Mereghetti, P., Fantucci, P., Grandori, R. & De Gioia, L. Free-energy landscape, principal component analysis, and structural clustering to identify representative conformations from molecular dynamics simulations: the myoglobin case. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 27, 889–899 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the generous support from the Ongoing Research Foundation program (ORF-2025-1436) by the King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A.S. is grateful to Ajman University, UAE for supporting this publication.

Funding

A.A.A acknowledges the generous support from the Ongoing Research Foundation program (ORF-2025-1436) by the King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A.S. is grateful to Ajman University, UAE for supporting this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., N.N.M.Z. and K.D. wrote the main manuscript text and A.S., A.A.A., M.S. and M.S.K. prepared all the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shamsi, A., Zain, N.N.M., Dinislam, K. et al. Exploring the binding of cinchonine with human transferrin: combined experimental and computational approaches. Sci Rep 15, 40660 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27571-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27571-z