Abstract

The extensive use of Portland cement significantly contributes to global carbon emissions, demanding sustainable alternatives in construction. This study investigates the combined influence of palm oil fuel ash (POFA), a supplementary cementitious material, and jute fiber (JF), a natural reinforcement, on the performance and eco-efficiency of concrete. Experimental tests assessed compressive, tensile, flexural strengths, modulus of elasticity, and ultrasonic pulse velocity, alongside embodied carbon and eco-strength efficiency. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed to model responses, while multi-objective optimization determined the ideal mix proportions. Results reveal that incorporating 0.10% JF with 10% POFA enhances mechanical performance by up to 26%, while 25% POFA substitution yields the lowest embodied carbon. The optimized blend (12.66% POFA and 0.244% JF) achieved an 86% desirability index, balancing strength and sustainability. These findings provide new evidence that the integration of agro-waste ash with natural fibers, supported by statistical optimization, offers a viable pathway for producing eco-efficient, high-performance concrete, thereby advancing sustainable construction practices. Future work may extend these findings through microstructural and durability assessment to further validate the long-term sustainability of POFA-JF concrete.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The building industry is a substantial contributor to carbon discharges globally because of the extensive usage of Portland cement (PC). Approximately 8% of global carbon emissions are from the cement industry1. In recent times, demands for sustainable construction materials have increased, and researchers are increasingly investigating innovative solutions and materials for low-carbon construction, ensuring the overall mechanical characteristics of concrete for resilient infrastructure2,3,4,5. One promising approach to lower the embodied carbon and enhance the overall characteristics of concrete is to use natural fibers and industrial by-products as supplementary cementitious materials (SCM)6,7,8. Jute fibers (JF) and palm oil fuel ash (POFA) are the two most promising components, as recent studies have shown significant impacts on concrete mechanical, durability, and environmental characteristics9,10.

The usage of natural fiber-reinforced concrete mixtures is recognized as a feasible alternative for cost-effective constructions in developing countries11. Due to their capacity for decomposition and ecological viability, natural fibers have been extensively used as strengthening materials12. Natural fibers contribute to the moderation of CO2 emissions released into the environment13. The building, automotive, packaging, architectural, and biomedical industries are progressively using bio-composites14. Fibers that are produced naturally are relatively more economical, resilient, as well as biodegradable than artificial alternatives15. Numerous natural fiber composites were recently proposed by researchers for use in various technological applications16. When used as reinforcing agents, natural fibers are thought to function as fracture stoppers and impede the development of cracks in cementitious materials, hence reducing catastrophic harm17. The usage of constant fiber reinforcement has led to the growth of an innovative building material characterized by superior tensile strength as well as versatility. Incorporating fiber reinforcement in the matrices is crucial for enhancing resilience and robustness18.

Use of jute fiber in concrete composite is considered a viable alternative due to its plentiful accessibility and economic efficiency, since these are sourced from perennial plants19. The quantity of JF is attributable to its broad availability20. These items feature a pentagonal or hexagonal cross-section, offering suitability for outdoor applications because of their insulation capacity, UV resistance, and antimicrobial characteristics20. Due to their remarkable physical characteristics, jute textiles are most appropriate to serve as a reinforcing material in lamination and bionic composite21. Jute textiles possess several functions. Jute fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) has adequate structural properties that meet industrial material standards and are also economically viable22. Jute fiber is a significant degradable fiber for its remarkable features, cost-effectiveness, abundant accessibility, and eco-friendly characteristics23. Jute and sisal fibers show significantly larger natural mechanical characteristics compared to those of palm and sugarcane fibers24. Physical indication of this phenomenon is well demonstrated in those materials reinforced with such appropriate fibers. Research findings indicate that JF have a tensile capacity in the range from 250 to 300 MPa25. This degree of strength is considered sufficient for many applications. Multiple studies have been undertaken to assess performance and influence properties of cementitious composite, focusing specifically upon the influence of prolonged, continuous jute fibers and short, discrete jute fibers26. Their assertion indicates that the integration of JF into concrete enhances the composite’s longevity, resistance to external stresses, and fracture resistance27. Numerous investigations indicate that JF may replace traditional fibers in building materials28. Multiple features, such as the nature and volume of fibers incorporated, can affect the properties of natural fiber-reinforced concrete composites (NFRCC)29. The properties of NFRCC can be affected by the fiber’s hydrophilic nature as well as the amount of fiber and filler incorporated into the composite30. To get optimal efficiency and enhanced usefulness, composites often need a significant amount of fiber content31. The ideal circumstance is essential for the effectiveness of concrete. The effect of fiber content on NFRCC properties is critically significant32. Several studies focused on the utilization of JF instead of using steel fibers24,33. Steel fiber is linked to rusting and expansion under heat challenges. The prior study conducted by Jawad et al.19 determined that the incorporation of jute fiber led to an increased fibrous area, thus resulting in a decrease in the flowability of the concrete. This subsequently increased the concrete’s roughness. The inclusion of 2% JF in concrete has been shown to enhance the material’s mechanical strength, and the analysis revealed that the incorporation of 2% JF leads to the greatest improvements in CS, STS, and FS. Incorporating JF into concrete beyond a 2% limit reduces the mechanical strength of the composite, whereas tests revealed that JF addition enhances the concrete’s resistance against DD, WA, DS, and acidic environments. In another study on the addition of JF in concrete, Islam et al.34 showed that with increased JF concentration in concrete, the flowability of fresh concrete declines. The results demonstrate that the decrease in flowability for concrete blends was more significant in samples including JF with an overall length of 20 mm and a ratio of dimension ratio of 200, in contrast to those with JF measuring 10 mm in length and a dimension ratio of 100. This occurrence arose due to the longer JF possessing a substantially larger surface area compared to volume ratio. The findings demonstrate a link between the length of curing and the achieved degree of compressive strength (CS). The study results demonstrate that incorporating a small quantity of 0.25% JF into concrete significantly enhanced its CS, irrespective of the length of fiber. Findings showed that incorporating JF in concrete reduced both the size and frequency of cracks in specimens tested for CS, STS, and FS. These tests confirmed that the occurrence of JF fibers helped limit the complete physical failure of the concrete samples. One more study showed by Muhammad et al.35, found that the accumulation of only a small percentage of JF, about 0.10% in concrete, has expressively enhanced the concrete’s mechanical characteristics in comparison to the reference mix. It was observed that raising the JF content from 0.10% to 0.20% mechanical properties of concrete.

Concurrently, palm oil fuel ash (POFA), a by-product of palm oil production, has garnered attention for its pozzolanic properties and potential to replace a portion of Portland cement36. By utilizing POFA, we can significantly decrease the embodied carbon of concrete while enhancing its durability and long-term performance. Bashar et al.37 asserted that POFA is a notable commercial pozzolanic waste material in Southeast Asia. The availability and quantity of POFA established a robust platform for investigators to examine this material’s potential as a primary foundation for the creation of ecologically welcoming and environmentally friendly materials, like geopolymer concrete. Supplementary cementitious materials are combined into concrete to improve their durability and strength through pozzolanic reactions. POFA, derived from palm-oil remains such as shells, empty fruit lots, and fibers, is produced as a byproduct when these wastes are burned at 850–1000 ℃ in palm-oil mills for energy generation. Mujah38 said that POFA is a by-product of the ignition of palm oil waste leftovers. It includes substantial concentrations of oxides of amorphous silicon and aluminum, respectively. Several investigations are currently underway to assess the efficacy of employing crushed-POFA as a grout in concrete mixtures. Tangchirapat et al.39 examined the application of ground-PO for improving the durability, permeation of water, as well as resistance to sulfates of concrete holding a significant quantity of recycled concrete aggregates (RCA). Muthusamy and Azzimah40 investigated the use of POFA in lightweight concrete and indicated that a 20% addition yielded optimal compressive strength, but up to 50% may still be employed for structural purposes. The findings of these previous studies indicated the decrease of POFA when incorporated in high-strength concrete (HSC), which may primarily be credited to the particulate volume’s coarseness, the substantial presence of unaltered carbon, and the increased loss during the process of combustion of unprocessed POFA. Additional researchers used the essential amount of processed POFA in the production of concrete and composite materials. The use of as much as 82% subspace replacement with GGBFS in alkali-activated mortar and concrete warrants attention. Additionally, treated-POFA is being utilized to progress the durability characteristics of concrete across several energy applications. Incorporating POFA into concrete was found to lower chloride removal efficiency, even when additional super-plasticizers were used, compared to concrete made with cedar peel ash41. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of POFA as a supplementary cementitious material due to its pozzolanic properties and JF as natural reinforcement.

While the individual effects of POFA and JF on concrete’s mechanical and durability properties have been the focus of several previous studies, a systematic investigation into the combined and potentially synergistic influence of these two materials, particularly with respect to both mechanical performance and embodied carbon reduction, remains limited. Furthermore, comprehensive correlation analysis, predictive response surface modeling, and multi-objective optimization of POFA-JF concrete have been largely unexplored. Therefore, the objective of this investigation are; (1) to systematically evaluate the combined effects of POFA and JF on concrete’s mechanical and non-destructive properties; (2) to assess the environmental performance in terms of embodied carbon and eco-efficiency; (3) to develop the predictive models using response surface methodology; and (4) to identify the optimal mix proportions by multi-objective optimization, balancing strength and sustainability.

Materials and methods

Materials and mix proportioning

The study employed ordinary Portland cement (OPC) in accordance with the ASTM C150M-15 standard. The POFA utilized in this research was taken from the local palm oil industry in Perak, Malaysia. POFA was properly sieved to eliminate the larger particles of ≥ 300 ųm. After sieving, POFA was ground in a Los Angeles abrasion machine for two hours to obtain a fine powder suitable for cement replacement. Previous studies report typical POFA fineness between 4000 and 5000 cm²/g, which was adopted as a reference level in this work and median particle size of approximately 11 ųm, confirmed by sieving. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) was conducted to determine the chemical composition of both POFA and OPC. Chemical composition of both POFA and OPC is summarized in Table 1.

The procurement procedure for the necessary components did not compromise on acquiring jute from local sources, due to its essential significance as a component of concrete. An evaluation was performed on the material’s qualities and, according to the jute characteristics provided by the supplier, to determine its appropriateness for concrete construction and associated testing trials. Evaluating the development of jute inside concrete, also measuring the structural integrity of the jute, were essential measures in improving the quality of FRC (fiber reinforced concrete) components42. The ideal bonding between jute and concrete enabled the formation of FRC elements with improved strength43. That approach confirms strong bonding between the jute and concrete. For the proposed study, micro silica was obtained from a local supplier, and its density, along with other relevant properties, was evaluated upon delivery. Its characteristics, including reduced water absorption, are closely linked to its appropriateness for use in materials with specific particle sizes and shapes. The polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (SP) was obtained from the Malaysian firm SIKA-KIMIA. The aggregates, fine and coarse, used in the experiments were sourced from the UTP laboratory, having SG values of 2.80 and 2.60, respectively. The marking curves for two sorts of aggregates are accessible in Fig. 1. Further, the tap water was used in mixing the concrete. Concrete mix proportions, incorporating varying amounts of JF and POFA, are outlined in Table 2.

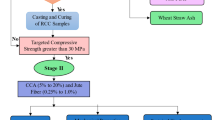

A reference mix was formulated following ACI 211.1–91 standards. Using Design Expert software version 13, mix designs with different POFA and JF contents were established. By using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), the study identified an optimal experimental design to assess the effect of POFA and JF on concrete properties and create predictive models for strength variation. This study involved two independent variables, POFA and JF, with POFA percentages in the range from 0 to 25% and JF from 0 to 0.5%. The upper limit for JF was selected because multiple studies have reported that increasing jute fiber content above 0.4–0.5% by volume leads to a decline in mechanical strength, workability, and fiber dispersion due to agglomeration and increased porosity. As such, a relatively low percentage of JF was maintained in this study, aligning with prior work that found optimal mechanical performance in the range of 0.10–0.40%9,42,44. Five dependent variables were included in the RSM: CS, STS, FS, MOE, and UPV.

Mixing and sample preparation

A cylindrical mixer with high shear was used to mix the ingredients. Initially, all dry components, cement, POFA, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, and micro silica were precisely restrained and varied in the cylindrical mixer for approximately 2 min. Afterwards, water and SP were gradually added to the dry mixture. The concrete was mixed for an additional five minutes before JF was incrementally introduced to ensure even distribution of the fiber throughout the concrete. After adding the fiber, mixing continued for another 3 to 4 min. Concrete specimens were created in cuboid molds measuring 100 mm x 100 mm, prepared according to ASTM C39 standards for CS testing45. STS samples with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 200 mm were cast following ASTM C49646. FS beams of 500 mm in length and 100 mm in width were made up in compliance with ASTM C78/C78M-2147. As per ASTM C469 standards, the MoE assessment was carried out on cylindrical samples measuring 300 mm in diameter and 100 mm in length48. For every test, a minimum of two specimens were evaluated following a curing period of 28 days. The UPV assessment was shown using 100 mm concrete cubes in compliance with the ASTM C597-09 specification49. The sample surfaces were carefully ground to ensure flatness and perpendicularity before positioning them between ultrasonic transducers at opposite ends along the longitudinal axis. The UPV value was then determined using Eq. (1). All specimens were cured under ambient laboratory conditions at room temperature for 28 days. For each test, at least two specimens were prepared and tested to ensure result consistency.

Results and discussion

Compressive strength

Figure 2 presents the CS results, indicating that the control concrete achieved a CS of 50 MPa. Incorporating 0.1% JF into the mix increased the CS by 16%, whereas raising the JF content to 0.25% led to only a 12% improvement, which was lower than that observed at 0.1% JF. When the OPC is replaced with 5% of POFA, it increases the CS by 10%. Adding 0.5% of JF with 5% substitution of OPC results in an increase in the CS by 6%. When the replacement level increased to 10% along with 0.1% of JF, it resulted in enhancing the CS by 26%. Raising the substitution level to 15% along with 0.25% of JF resulted in enhancing the CS by 22%, while the same level of substitution with 0.5% of JF showed only 6% rise in CS. Furthermore, with 20% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF caused a drop in strength of 8% in contradiction to the control mix. Consequently, increasing the substitution level to 25% without any JF content resulted in reducing the strength by 34%, while accumulation of 0.25% of JF in concrete with an analogous level of change, CS reduces by 24%. Conversely, increasing the JF contents to 0.5% with 25% OPC substitution resulted in reducing the strength by 28% in contrast to the control mix. The results indicate that incorporating 0.1% JF into the concrete produced the optimal CS, with a 10% cement replacement combined with 0.1% JF delivering the highest strength among all tested mixtures. The reduction in strength at higher POFA and JF levels was possibly due to excessive cement dilution and fiber agglomeration, which may increase porosity and hinder matrix continuity50. At high POFA contents, unreacted ash particles act as inert fillers, while excessive fibers may create weak interfacial zones that restrict effective stress transfer within the composite51. A prior investigation by Muhammad et al.35 studied the impression of JF on both fresh and hardened concrete properties, revealing that a mix with 0.10% JF achieved the highest CS, improving by 6.77% compared to the control mix. One more research carried out by Chinnu et al.52 to compare the benefits of utilizing POFA in comparison to fly ash and slag. They found that 10% of POFA is the optimal percentage to be used as an SCM; beyond this value concrete characteristic tends to degrade. In this research, it was also evaluated that 0.10% of JF, along with 10% cement substitution, results in optimal CS.

Figure 3 illustrates how POFA and JF influence the CS of concrete using both 2D and 3D response surface plots, where the red-shaded areas represent the maximum CS values. The optimal combination was found to be 0.10% JF with 10% POFA, which resulted in the highest CS. Beyond these levels, increases in fiber content and POFA percentage led to a reduction in CS.

Split tensile strength

Figure 4 displays the STS results, showing that the control concrete achieved an STS of 4.94 MPa. Incorporating 0.1% JF increased the strength by 7.70%, whereas raising the JF content to 0.25% led to only a 5.83% improvement, which was lower than that achieved with 0.1% JF. When the OPC is replaced with 5% of POFA, it increases the STS by 4.88%. Adding 0.5% of JF with 5% substitution of OPC results in increasing the STS by 2.95%. When the replacement level increased to 10% along with 0.1% of JF, it resulted in enhancing the STS by 12.24%. Raising the substitution level to 15% along with 0.25% of JF resulted in increasing the STS by 10.45%, while the same level of substitution with 0.5% of JF in it showed 1% decrease in STS, in contrast to the control mix. Furthermore, with 20% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF resulted in a reduction of strength by 4.08% in contrast to the reference mix. Consequently, growing the substitution level to 25% without any JF content resulted in reducing the STS by 36.94%, while accumulation of 0.25% of JF in concrete with an analogous level of change, STS reduces by 26.96%. Conversely, raising the JF contents to 0.5% with 25% OPC substitution resulted in reducing the STS by 33.32% in comparison to the reference mix. From the findings, it was discovered that the accumulation of 0.1% of JF in concrete results in optimal STS. A 10% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF has shown the maximum STS in comparison to other mixes. Similarly, reduction in mechanical strengths at higher POFA and JF content is likely due to excessive dilution of cement and fiber agglomeration50,51. Earlier, an investigation conducted by Muhammad et al.35 initiate that 0.10% of JF in concrete has developed in increasing the STS by 6.91% and found that 0.10% of JF in concrete is the optimal value. Furthermore, an experimental research led by Sooraj et al.53 found that growing the additional level of cement with POFA from 10 to 20 resulted in enhancing the STS but when this values has been increased beyond 20 demonstrated a decline in STS, which shows from 10% to 20% substitution of cement with may results in better STS. In the present research, it was also found that when 0.10% of JF is added to concrete along with 10% of POFA concrete demonstrates the maximum STS.

Figure 5 depicts how POFA and JF affect the STS of concrete, illustrated through 2D as well as 3D response surface plots. The area in red on these plots represents the highest STS values observed. The combination of a 0.10% JF and 10% POFA as a cement replacement resulted in the highest STS, while increases beyond these amounts in fiber and POFA content caused a decline in STS.

Flexural strength

Results of FS are illustrated in Fig. 6, indicating that the control concrete recorded an FS of 4.38 MPa. Adding 0.1% JF to the concrete mix improved the strength by 7.70%, whereas raising the JF content to 0.25% produced only a 5.83% gain, which was lower than the improvement achieved with 0.1% JF. When the OPC is replaced with 5% of POFA, it increases the FS by 4.88%. Adding 0.5% of JF with 5% substitution of OPC results in increasing the FS by 2.95%. When the replacement level increased to 10% along with 0.1% of JF, it resulted in enhancing the FS by 12%. Raising the substitution level to 15% along with 0.25% of JF resulted in the enhancement of FS by 10.45%, while the same level of substitution with 0.5% of JF showed a 6.70% decrease in FS. Moreover, replacing 20% of the cement with 0.1% JF led to an 11.83% decrease in strength associated to the reference mix. Consequently, increasing the substitution level to 25% without any JF content resulted in reducing the strength by 33.81%, while accumulation of 0.25% of JF in concrete with an analogous level of change, FS reduces by 23.08%. Conversely, increasing the JF content to 0.5% with 25% OPC substitution resulted in reducing the FS by 35.67% in contrast to the control mix. The results revealed that incorporating 0.1% JF into the concrete mix produced the optimal FS. A 10% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF has shown the maximum FS in comparison to other mixes. In a prior study by Sooraj et al.53, it was evaluated that 10 to 20% replacement of cement with POFA results in optimal FS, with 10% replacement having higher FS. Research conducted on JF accumulation in concrete by Muhammad et al.9 evaluated that 0.10% of JF results in enhancing the FS by 9.63% in the control mix. This study also evaluated that both 0.10% of JF along with 10% replacement of OPC with POFA have demonstrated the higher FS in contrast reference mix proportion.

Figure 7 shows the impression of POFA and JF on the FS of concrete through both 2D as well as 3D response plots. The areas in red on these graphs highlight the highest FS values achieved. The optimal FS was recorded at 0.10% JF combined with 10% POFA. Increasing the fiber content beyond 0.10% or the POFA level above 10% results in a reduction of FS.

Modulus of elasticity

Figure 8 presents the MOE results, showing that the control concrete recorded an MOE of 33.23 GPa. Incorporating 0.1% JF into the concrete mix increased the MOE by 7.70%, whereas raising the JF content to 0.25% improved it by only 5.83%, which was lower than the gain observed with 0.1% JF. When the OPC is replaced with 5% of POFA, it increases the MOE by 4.88%. Adding 0.5% of JF with 5% substitution of OPC results in increasing the MOE by 2.95%. When the replacement level increased to 10% along with 0.1% of JF, it resulted in enhancing the MOE by 12.24%. Raising the substitution level to 15% along with 0.25% of JF resulted in improving the MOE by 10.45%, while the same level of substitution with 0.5% of JF in it showed 1% decrease in MOE, in contrast to the reference mix. Furthermore, with 20% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF resulted in reducing the MOE by 4.08% in dissimilarity to the control mix. Consequently, increasing the substitution level to 25% without any JF content resulted in reducing the MOE by 18.75%, while accumulation of 0.25% of JF in concrete with a analogous level of replacement, the MOE reduces by 12.82%. Conversely, expanding the JF content to 0.5% with 25% OPC substitution resulted in reducing the MOE by 15.14% in contrast to the reference mix. From the findings, it was found that the accumulation of 0.1% of JF in concrete results in optimal MOE. A 10% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF has shown the maximum MOE in comparison to other mixes. A study executed by Tiwari et al.54 originate that adding JF to concrete has caused in enlightening the total strength and stiffness of concrete, which may result in increasing the concrete MOE. Another study found that inclusion of POFA more than 30% resulted in a decline in the MOE, while 10% to 20% substitution of POFA with OPC resulted in enhancing the MOE55.

Figure 9 presents the impacts of POFA and JF on the MOE of concrete, displayed through 2D and 3D response surface plots. The red-highlighted regions indicate where the MOE reaches its peak values. The highest MOE is observed with fiber content slightly above 0.10% but below 0.30%, combined with 10% POFA. When fiber content goes beyond 0.25% or POFA exceeds 10%, a decline in MOE is noticeable.

Ultra-sonic pulse velocity

Figure 10 displays the UPV results, indicating that the control concrete achieved a UPV of 3.5 Km/sec. Adding 0.1% JF to the mix increased the UPV by 10.28%, while raising the JF content to 0.25% improved it by only 8%, which was less than the gain observed with 0.1% JF. When the OPC is replaced with 5% of POFA, it increases the UPV by 4.28%. Adding 0.5% of JF with 5% substitution of OPC results in an increase in the UPV by 2.57%. When the replacement level increases to 10% along with 0.1% of JF, it leads to enhancing the UPV by 13.14%. Growing the substitution level to 15% along with 0.25% of JF caused an increase in the UPV by 12.57%, while the same level of substitution with 0.5% of JF showed only a 1.42% rise in UPV. Furthermore, with 20% substitution of cement with 0.1% of JF, lead to reduction in UPV by 4.85% in difference to the control mix. Consequently, increasing the replacement level to 25% without any JF content resulted in a reduction of the UPV by 18%, while the accumulation of 0.25% JF in concrete with a analogous level of replacement resulted in a reduction of the UPV by 8.28%. Conversely, increasing the JF content to 0.5% with 25% OPC substitution resulted in lowering the UPV by 14.57% in comparison to the control mix. From the findings, it was found that the accumulation of 0.1% of JF in concrete results in optimal UPV. A 10% substitution of cement along with 0.1% of JF has shown the maximum UPV in comparison to other mixes. In a prior study directed by Kumar et al.56 initiate that a higher percentage of POFA within the concrete matrix resulted in reducing the UPV of concrete, which may be credited to the lower density and higher porosity in concrete. However, concrete incorporating POFA demonstrated greater durability compared to the control mix. A comprehensive research conducted by Ahmad et al.19 assessed the effects of JF on UPV of concrete. It was found that prior studies have indicated an increase in UPV by the accumulation of JF because it increases the compactness of concrete and enhances the overall structure of concrete.

Figure 11 displays the impression of POFA and JF on the UPV of concrete using 2D and 3D plots. The areas in red represent the highest UPV values. The optimal UPV occurs with fiber content slightly above 0.10% but below 0.35%, alongside 10% POFA. Increases in fiber content beyond 0.35% or POFA above 10% lead to a reduction in UPV.

Environmental sustainability assessment

Embodied carbon

For each concrete mix, the EC was determined using emission factors for all constituents as reported in the literature, enabling a comprehensive sustainability evaluation. Below is Table 3, which presents the value of the EC factor for each constituent. Regarding POFA, as per available literature, there is no available literature. As it is a waste material, being a waste material, it does not have any EC factor defined in available literature, but some factors need to be considered to use POFA in concrete, such as the EC factor of transportation and electricity. For this study, the EC factor of transportation was considered as 0.204 kg.CO2/tonne.km57 and for electricity 0.5 kg.CO2/kWh58. For 1 tonne means 1000 Kg of POFA, the total carbon footprint can be calculated considering a 50 Km distance for transportation of POFA from the local industry within the state of Perak to the laboratory (as POFA was collected within 50 Km area) and considering 200 kWh utilization of electricity to process the POFA. In absence of concrete literature for POFA grinding, we adopted a conservative estimate of 200 kWh per tonne. For comparison, typical cement grinding in industrial plants requires about 100–150 kWh per tonne of cement59. We opted for a higher value to ensure the embodied carbon estimate errs on the cautious side.

Total embodied carbon can be calculated using the formula;

so,

The reference concrete exhibited an EC of 542.58 kg.CO2/kg, as illustrated in Fig. 12. Incorporating 0.1% JF into the concrete caused a slight increase in the EC value by 0.06%, whereas raising the JF content to 0.25% resulted in only a 0.15% increase. Additionally, substituting 5% of cement with POFA led to a 3.96% reduction in the EC factor. When 0.5% JF was added at the same cement replacement level, the EC was reduced by 3.65%. Increasing the replacement to 10% combined with 0.1% fiber further lowered the EC by 7.86%. At a 20% substitution level with 0.1% fiber, the EC reduction reached 15.79%. With a 25% cement replacement and no fiber, the EC decreased by 19.82%; adding 0.25% fiber at this level resulted in a 19.66% reduction. Increasing fiber to 0.5% under the same 25% substitution brought about a 19.50% decrease in EC. Among all mix designs, the highest POFA replacement of 25% produced the lowest EC in the concrete. This aligns with expectations; as higher cement replacement levels reduce EC due to POFA having a lower embodied carbon factor compared to OPC.

Concrete’s eco-efficiency

ESE was calculated using Eq. (2). Selecting a concrete mix solely based on EC is insufficient; evaluating ESE is crucial to ensure the long-term sustainability and durability of the concrete mix65.

CS28 denotes the compressive strength of concrete measured at 28 days, and EC refers to the embodied carbon linked with the specific concrete mixture.

The reference concrete exhibited an ESE of 0.092 kg CO2/MPa/kg, as shown in Fig. 13. Incorporating 0.1% JF in the concrete increased the ESE by 15.92%, while raising the JF content to 0.25% led to a smaller increase of 11.82%. Additionally, substituting 5% of cement with POFA improved the ESE by 12.45%, and when combined with 0.5% JF at the same substitution level, the ESE rose by 14.16%. Increasing the replacement to 10% with 0.1% fiber content resulted in a significant ESE boost of 30.24%. At a 20% POFA replacement with 0.1% fiber, the ESE increased by 14%. When 25% of cement was replaced without fiber addition, the ESE improvement was 4.76%; adding 0.25% fiber at this substitution level raised the ESE by 9.54%. Finally, increasing fiber content to 0.5% with a 25% POFA replacement led to an additional 1.87% increase in ESE.

Analysis of variance by RSM

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) uses data collected from experiments to explore and quantify the relationships between various input factors and the outcomes measured66,67,68,69. These relationships are typically captured through mathematical models, which may be linear or polynomial, to reflect how the response variables behave under different conditions. This study evaluated concrete performance using seven indicators, including CS, STS, FS, MoE, and UPV. Model development employed Partial Sum of Squares Type III, incorporating factors normalized to values of -1, 0, and + 1 to represent their minimum, mid-point, and maximum levels70. Analysis indicated that a quadratic model provided the superlative fit for CS, FS, MoE, and UPV, while a cubic model was most appropriate for STS, as detailed in Eqs. (3–7). The selection of quadratic and cubic models for various responses was based on the statistical adequacy criteria automatically computed by Design Expert 13, where models with the highest R², adequate precision, and significant F- and p-values were selected as the best fits.

In the presented equations, variable “A” represents the total amount of JF, while “B” indicates the quantity of POFA. Model validation was carried out through ANOVA, using a 95% confidence level and a significance threshold of 5%71,72. Within this context, a statistically significant effect indicates that the model variables have a meaningful influence on the response outcomes. Evaluation of the results showed that each model was statistically significant, as its p-value was below 0.05 (Table 4). Notably, the independent variable “A” consistently affected all response parameters, demonstrated by p-values below 5%72,73. An important measure for determining model adequacy is the ‘lack of fit’ p-value, which should be greater than 0.05 for an acceptable fit9. All models in this study satisfied the fit criteria based on the lack of fit results. The detailed findings from ANOVA for every response are provided in Table 4.

Model fit statistics are provided in Table 5, highlighting essential parameters for assessing how well the proposed models perform. Among these indicators, the coefficient of determination (R2) serves as an important measure of how accurately the model reflects the observed data74. Higher R2 percentages suggest a sturdy correlation between the model’s predictions and the actual outcomes, reflecting robust model performance75. For the models generated in this study, R2 values ranged from 95.45% to 99.83%, underscoring their reliability. The evaluation also incorporated adjusted R2 and predicted R2 to further judge model quality65. A key requirement is that the variance between adjusted and anticipated R2 should remain within two units, a condition successfully met by all models in this analysis.

Diagnostic plots

Diagnostic plots play an important role in evaluating and validating the statistical models developed in this study76. The diagnostic charts presented (Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18) allow for assessment of model adequacy, consistency, and the detection of any influential or outlier data points77. A key tool in this evaluation is the standardized residual plot78, which depicts how residuals are distributed. When residuals follow a linear trend, it suggests the model fits the data well, while noticeable deviation from linearity may indicate that the model does not adequately capture the underlying data-generating process79. In this research, the standardized residual plots demonstrate that the developed models achieve a high level of accuracy. Additionally, ‘Actual vs. Predicted’ plots provide insight into the correspondence between experimentally measured values and those predicted by the models80. Strong model performance is shown when the plotted points closely follow the 45-degree reference line79. The results show that the data points closely follow a straight line, demonstrating the accuracy and robustness of the developed models.

Optimization of responses

This research primarily focuses on applying optimization algorithms to identify the best combination of input factors that can achieve favorable response outcomes81. Since multiple response variables are involved, the optimization approach must carefully balance inputs to realize optimal results73. To accomplish this, both input and output variable ranges were precisely defined so the objectives remain within prescribed boundaries. For this study, the objective function was formulated to keep JF within its allowed range while maximizing the impact of POFA. The specific optimization goals for individually response variable are presented in Table 6. The effectiveness of the optimization is calculated using the desirability index (where 0 ≤ d ≤ 1), with greater values reflecting more successful outcomes70.

After defining these constraints, optimization was performed, leading to the determination of optimization ramps as depicted in Fig. 19; Table 6. These figures present the optimal values for each response and their corresponding desirability scores. Results indicate that the most favorable input levels are JF = 0.244 and POFA = 12.66. With these values, the model forecasts optimized responses of 61.29 MPa for CS, 5.55 MPa for STS, 4.91 MPa for FS, 36.92 GPa for MoE, and 3.944 km/sec for UPV. The desirability value achieved was 0.86 (86%), underscoring the robustness of this optimization approach when considering multiple performance outcomes simultaneously.

Model validation

To confirm the predictive models and the optimization procedure, experimental testing was conducted using the optimized input mixture containing BF and CF at the levels of JF = 0.244 and POFA = 12.66. Test samples prepared with this optimized mix were evaluated for CS, STS, FS, MoE, and UPV. The experimental outcomes were then associated with the standards predicted by the models. Notably, the absolute relative difference (ARD) among the experimental and anticipated responses was found to be less than 5% across all tests, confirming the consistency and precision of the recognized estimate models within this study70. The ARD was measured using Eq. (8), and the detailed values for all responses are presented in Table 7.

Conclusion

This research examined the combined influence of POFA and JF on the mechanical and environmental aspects of concrete. A comprehensive sequence of trials was conducted to measure compressive strength (CS), split tensile strength (STS), ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), flexural strength (FS), modulus of elasticity (MOE), electrical conductivity (EC), and energy-saving efficiency (ESE). RSM was utilized to develop anticipated models for all response variables. Finally, multiple objectives optimization was performed to regulate the optimal values for all considered responses. Based on the experimental results and analyses presented, the conclusions wan from this research are as follows:

-

(1)

To study the hybrid effects of POFA and JF, there were two variables for developing RSM response models with varying percentages of POFA (0 ≥ 25) and JF (0 ≥ 0.5). In this investigation, dependent variables consist of CS, STS, FS, MOE, and UPV.

-

(2)

Quadratic models were estimated as significant for CS, FS, MOE, and UPV, while the cubic model was found significant for STS.

-

(3)

An ANOVA was conducted for every response model at a 95% confidence level (5% significance level). The coefficients of determination (R²) were statistically significant, ranging from 95.45% to 99.83% for all analyzed responses.

-

(4)

From the investigation, it was found that the addition of 10% POFA along with 0.1% of JF demonstrated the optimal mechanical properties. It was evaluated that CS, STS, FS, and MOE increase by 26%, 12.24%, 12% and 11.99% respectively, in contrast to the reference mix.

-

(5)

Increasing the cement replacement level to 10% POFA combined with 0.1% JF leads to a 13.14% improvement in UPV. This suggests that substituting 10% of OPC with POFA along with 0.1% JF is the optimal mix ratio, as exceeding these amounts results in a decline in concrete properties.

-

(6)

The amalgamation of POFA as a cement additional reduces the EC of the mix, attributable to POFA’s lower EC compared to OPC. Specifically, a concrete mixture containing 25% POFA without any JF recorded the lowest EC value, which is approximately 19.82% less than that of the control mix.

-

(7)

Results related to ESE demonstrate that a concrete blend with 15% POFA and 0.25% JF exhibits the highest eco-efficiency, outperforming the reference mix by about 38.22%.

-

(8)

Multi-objective optimization determined the best variable levels as POFA = 12.66% and JF = 0.244%, successfully achieving targeted improvements across all response variables while keeping them within acceptable limits. Experimental validation confirmed that the deviation between measured and predicted values remained within 5%.

Future directions

As this research study purely focuses on concrete’s mechanical characteristics, for future research, it is directed to perform further research on micro-structure to examine the interaction between fibers and POFA, and also analyze the process of hydration when using POFA as a supplementary cementitious material. Furthermore, future research may focus on the impact of adding other types of natural fibers in combination with POFA, such as jute-hemp or jute-sisal hybrid fibers, to the concrete mixture. A variety of mixtures tested may result in further optimization of the balance between mechanical properties and environmental sustainability. Long-term durability testing of POFA-jute fiber-reinforced concrete under harsh temperature, humidity, and freeze-thaw conditions can be conducted. Other very promising areas could be testing for various fiber treatments or other modifications that possibly will further improve the bonding with the cement substrate for increased mechanical performance. Moreover, the scalable use of POFA, a widely available industrial byproduct, combined with abundant natural fibers like jute, offers a cost-effective pathway toward reducing the embodied carbon footprint of concrete at a commercial scale. Investigations could also be done on how to scale this technology of sustainable concrete up to the real scale of construction projects, including supportive studies on economic viability and life cycle costs for wider diffusion in the industry. To understand the hydration kinetics of POFA as a cementitious material, x-ray diffraction analysis should be conducted.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. The corresponding author of this manuscript shall be contacted to provide the requested data.

References

York, I. N. & Europe, I. Concrete needs to lose its colossal carbon footprint. Nature 597 (7878), 593–594. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02612-5 (2021).

Khan, M. & McNally, C. A holistic review on the contribution of civil engineers for driving sustainable concrete construction in the built environment. Dev. Built Environ. 16, 100273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100273 (2023).

Ansari, M. A., Shariq, M. & Mahdi, F. Multi-optimization of FA-BFS based geopolymer concrete mixes: a synergistic approach using grey relational analysis and principal component analysis. Structures 71, 108007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.108007 (2025).

Ansari, M. A., Shariq, M. & Mahdi, F. Assessment of geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: a Scientometric-Aided review. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. 30 (2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1061/jsdccc.sceng-1627 (2025).

Saxena, A., Sulaiman, S. S., Shariq, M. & Ansari, M. A. Experimental and analytical investigation of concrete properties made with recycled coarse aggregate and bottom ash. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 8 (7), 197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-023-01165-y (2023).

Althoey, F., Ansari, W. S., Sufian, M. & Deifalla, A. F. Advancements in low-carbon concrete as a construction material for the sustainable built environment. Dev. Built Environ. 16, 100284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100284 (2023).

Ansari, M. A., Shariq, M. & Mahdi, F. Geopolymer concrete for clean and sustainable construction – a state-of-the-art review on the mix design approaches. Structures 55, 1045–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.06.089 (2023).

Ansari, M. A., Shariq, M. & Mahdi, F. Multioptimization of FA-Based geopolymer concrete mixes: a synergistic approach using Gray relational analysis and principal component analysis. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. 30 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1061/jsdccc.sceng-1556 (2025).

Khan, M. B. et al. Effects of Jute Fiber on Fresh and Hardened Characteristics of (Wiley, 2023).

Abu Aisheh, Y. I. Palm oil fuel Ash as a sustainable supplementary cementitious material for concrete: a state-of-the-art review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01770 (2023).

Khalid, M. Y. et al. Natural fiber reinforced composites: sustainable materials for emerging applications. Results Eng. 11, 100263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2021.100263 (2021).

Elanchezhian, C. et al. Review on mechanical properties of natural fiber composites. Mater. Today Proc. 5, 1785–1790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.276 (2018).

Sai Shravan Kumar, P. & Viswanath Allamraju, K. A review of natural fiber composites [Jute, Sisal, Kenaf]. Mater. Today Proc. 18, 2556–2562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.113 (2019).

Nagaraj, C., Mishra, D. & Reddy, J. D. P. Estimation of tensile properties of fabricated multi layered natural jute fiber reinforced E-glass composite material. Mater. Today Proc. 27, 1443–1448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.864 (2020).

Elfaleh, I. et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: an eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 19, 101271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101271 (2023).

Yamini, P., Rokkala, S., Rishika, S., Rani, P. M. & Arul Kumar, R. Mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced composite structure, Mater. Today Proc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.547.

Naveen, M. et al. Experimental Investigation on Jute Fiber Concrete Under Various Environmental Conditions (Springer, 2024).

Ahmad, J. & Zhou, Z. Mechanical properties of natural as well as synthetic fiber reinforced concrete: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 333, 127353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127353 (2022).

Ahmad, J., Arbili, M. M., Majdi, A., Althoey, F. & Deifalla, A. F. Performance of concrete reinforced with jute fibers (natural fibers): a review. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1177/15589250221121871.

Islam, M. S. & Ahmed, S. J. U. Influence of jute fiber on concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 189, 768–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.048 (2018).

Mushtaq, B., Ahmad, F., Nawab, Y. & Ahmad, S. Optimization of the novel jute Retting process to enhance the fiber quality for textile applications. Heliyon 9 (11), e21513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21513 (2023).

Yasin, Y. et al. Experimental evaluation of mechanical characteristics of concrete composites reinforced with jute fibers using bricks waste as alternate material for aggregates. Next Mater. 5, 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxmate.2024.100232 (2024).

Özen, S., Benlioğlu, A., Mardani, A., Altın, Y. & Bedeloğlu, A. Effect of graphene oxide-coated jute fiber on mechanical and durability properties of concrete mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 448, 138225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138225 (2024).

Song, H., Liu, J., He, K. & Ahmad, W. A comprehensive overview of jute fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15, e00724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00724 (2021).

Jo, B. W., Chakraborty, S. & Lee, Y. S. Hydration study of the polymer modified jute fibre reinforced cement paste using analytical techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.086 (2015).

Islam, M. Z., Sabir, E. C. & Syduzzaman, M. Experimental investigation of mechanical properties of jute/hemp fibers reinforced hybrid polyester composites. SPE Polym. 5 (2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/pls2.10119 (2024).

Hossain, M. A., Datta, S. D., Akid, A. S. M., Sobuz, M. H. R. & Islam, M. S. Exploring the synergistic effect of fly Ash and jute fiber on the fresh, mechanical and non-destructive characteristics of sustainable concrete. Heliyon 9 (11), e21708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21708 (2023).

Affan, M. & Ali, M. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced concrete under freeze-thaw conditions for pavement applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 323, 126599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126599 (2022).

Chakrabortty, A. & Begum, H. A. An approach to improve the existing ribbon Retting of jute fibre using concrete tank and natural catalyst. Heliyon 9 (9), e19488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19488 (2023).

Nambiar, R. A. & Haridharan, M. K. Mechanical and durability study of high performance concrete with addition of natural fiber (jute). Mater. Today Proc. 46, 4941–4947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.339 (2021).

Rajkumar, R., Navin Ganesh, V., Mahesh, S. R. & Vishnuvardhan, K. Performance evaluation of E-waste and Jute Fibre reinforced concrete through partial replacement of Coarse aggregates. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 6242–6246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.689 (2021).

Sultana, N., Zakir Hossain, S. M., Alam, M. S., Islam, M. S. & Al Abtah, M. A. Soft computing approaches for comparative prediction of the mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced concrete. Adv. Eng. Softw. 149, 102887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2020.102887 (2020).

Shadheer Ahamed, M., Ravichandran, P. & Krishnaraja, A. Natural fibers in concrete – a review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1055 (1), 012038. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1055/1/012038 (2021).

Islam, M. S. & Ahmed, S. J. Influence of jute fiber on concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 189, 768–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.048 (2018).

Khan, M. B. et al. Effects of jute fiber on fresh and hardened characteristics of concrete with effects of jute fiber on fresh and hardened characteristics of concrete with environmental assessment. No June. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071691 (2023).

Hasan, N. M. S. et al. Eco-friendly concrete incorporating palm oil fuel ash: fresh and mechanical properties with machine learning prediction, and sustainability assessment. Heliyon 9 (11), e22296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22296 (2023).

Bashar, I. I. et al. Engineering properties and fracture behaviour of high volume palm oil fuel Ash based fibre reinforced geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.022 (2016).

Mujah, D. Compressive strength and chloride resistance of Grout containing ground palm oil fuel Ash. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 712–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.066 (2015).

Tangchirapat, W., Khamklai, S. & Jaturapitakkul, C. Use of ground palm oil fuel Ash to improve strength, sulfate resistance, and water permeability of concrete containing high amount of recycled concrete aggregates. Mater. Des. 41, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2012.04.054 (2012).

Muthusamy, K. & Zamri, N. A. Exploratory study of palm oil fuel ash as partial cement replacement in oil palm shell lightweight aggregate concrete. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 8, 150–152. https://doi.org/10.19026/rjaset.8.953 (2014).

Abdullah, E., Mirasa, A. K. & Asrah, H. Review on the effect of palm oil Fuel ash (POFA) on concrete.J. Ind. Eng. Res. 1, 1–4 (2015).

Zhang, T., Yin, Y., Gong, Y. & Wang, L. Mechanical properties of jute fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete. Struct. Concr. 21 (2), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201900012 (2020).

Zakaria, M., Ahmed, M., Hoque, M. & Islam, S. Scope of using jute fiber for the reinforcement of concrete material. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2, 256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40689-016-0022-5 (2016).

Ahmad, J. et al. Performance of concrete reinforced with jute fibers (natural fibers): a review. J. Eng. Fiber Fabr. 17, 15589250221121872. https://doi.org/10.1177/15589250221121871 (2022).

Sulfate, M. iTeh Standards iTeh Standards,” Des. E 778 – 87 (Reapproved 2004), vol. i, no. Reapproved 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1520/C0039 (2018).

International, A. S. T. M. Astm C496/C496M. ASTM Stand. B 545–545 -3 (2008).

Ag-, C., Statements, B. & Pycnometer, W. Standard test method for iTeh standards iTeh standards 22–25 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0078.

[ASTM] American Standard Testing and & Material ASTM C469-02 standard test method for static modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio of concrete in compression. ASTM Stand. B. 4, 1–5 (2002). https://portales.puj.edu.co/wjfajardo/mecanicadesolidos/laboratorios/astm/C469.pdf.

American Society for Testing and & Material, A. S. T. M. C. 597-02, standard test method for pulse velocity through concrete. United States: ASTM. 04 (02), 3–6 (2003).

Khan, M. et al. Effects of jute fiber on fresh and hardened characteristics of concrete with environmental assessment. Buildings 13, 1691. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071691 (2023).

Mirza, J., Hussin, M. & Ismail, M. Effects of Palm Oil Fuel Ash as Micro-Filler on Interfacial Porosity of Polymer Concrete 99–111 (Springer, 2019).

Chinnu, S. N., Minnu, S. N., Bahurudeen, A. & Senthilkumar, R. Influence of palm oil fuel Ash in concrete and a systematic comparison with widely accepted fly Ash and slag: a step towards sustainable reuse of agro-waste Ashes. Clean. Mater. 5, 100122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2022.100122 (2022).

Sooraj, V. M. Effect of palm oil fuel Ash (POFA) on strength properties of concrete. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 3, 2250–3153 (2013).

Tiwari, S., Sahu, A. & Pathak, R. Mechanical properties and durability study of jute fiber reinforced concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 961, 12009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/961/1/012009 (Nov. 2020).

Osman, M. H., Adnan, S. H., binti, N. I., Mazlin & Wan Jusoh, W. A. Properties of concrete containing palm oil fuel Ash and expanded polystyrene beads. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 12 (9), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2020.12.09.010 (2020).

Kumar, A. G., Ramasamy, S., Venkatachalam, B. K. K. & Nachimuthu, B. Experimental investigation on the viability of palm oil fuel Ash as a sustainable additive in high performance concrete. Rev. Mater. 29, 2. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-7076-RMAT-2024-0149 (2024).

Gan, V. J. L. et al. Automatic Measurements of Carbon Emissions From Building Materials and Construction for Sustainable Structural Design of Tall Commercial Buildings 7–8 (Wiley, 2020).

Chen, L. & Wemhoff, A. P. Predicting embodied carbon emissions from purchased electricity for united States counties. Appl. Energy. 292, 116898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116898 (2021).

Dahanni, H. et al. Life cycle assessment of cement: are existing data and models relevant to assess the cement industry’s climate change mitigation strategies? A literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134415 (2024).

Collins, F. Inclusion of carbonation during the life cycle of built and recycled concrete: influence on their carbon footprint. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 15, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-010-0191-4 (2010).

Turner, L. K. & Collins, F. G. Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) emissions: a comparison between geopolymer and OPC cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 43, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.01.023 (2013).

Cushman, B. R. Energy consumption Energy type 1–12 (2017). http://www.dartmouth.edu/~cushman/books/Numbers/Chap1-Materials.pdf.

Thilakarathna, P. S. M. et al. Embodied carbon analysis and benchmarking emissions of high and ultra-high strength concrete using machine learning algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121281 (2019).

Kumar, R., Shafiq, N., Kumar, A. & Jhatial, A. A. Investigating embodied carbon, mechanical properties, and durability of high-performance concrete using ternary and quaternary blends of metakaolin, nano-silica, and fly Ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28 (35), 49074–49088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13918-2 (2021).

Ghani, M. U. et al. Mechanical and environmental evaluation of PET plastic-graphene nano platelets concrete mixes for sustainable construction. Results Eng. 21, 101825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101825 (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. Factors influencing adoption of digital twin advanced technologies for smart City development: evidence from Malaysia. Buildings 13 (3), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030775 (2023).

Waqar, A., Basit, M., Talal, M. & Radu, D. Investigating the synergistic effects of carbon fiber and silica fume on concrete strength and Eco-Efficiency case studies in construction materials investigating the synergistic effects of carbon fiber and silica fume on concrete strength and eco-efficie. No Febr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e02967 (2024).

Waqar, A., Khan, M. B., Najeh, T., Almujibah, H. R. & Benjeddou, O. Performance-based engineering: formulating sustainable concrete with sawdust and steel fiber for superior mechanical properties. Front. Mater. 11, 1452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2024.1428700 (2024).

Khan, M. B., Waqar, A., Bheel, N., Shafiq, N. & Sor, N. H. Optimization of fresh and mechanical characteristics of carbon fiber-reinforced concrete composites using response surface technique 1–32 (2023).

Khan, M. B. et al. Enhancing the mechanical and environmental performance of engineered cementitious composite with metakaolin, silica fume, and graphene nanoplatelets. Constr. Build. Mater. 404, 133187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133187 (2023).

Waqar, A. & Almujibah, H. Factors influencing adoption of digital twin advanced technologies for smart City development: evidence from Malaysia. No March. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030775 (2023).

Waqar, A., Skrzypkowski, K., Almujibah, H., Zagórski, K. & Khan, M. B. Success of implementing cloud computing for smart development in small success of implementing cloud computing for smart development in small construction projects. No May. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095713 (2023).

Tahir, H., Khan, M. B., Shafiq, N., Radu, D. & Nyarko, M. H. Optimisation of mechanical characteristics of Alkali-Resistant glass fibre concrete towards sustainable construction sustainability optimisation of mechanical characteristics of Alkali-Resistant glass fibre concrete towards sustainable construction. No July. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411147 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Effect of volcanic pumice powder Ash on the properties of cement concrete using response surface methodology. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-023-00265-7 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Limitations to the BIM-based safety management practices in residential construction project. Environ. Challenges. 14, 100848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100848 (2024).

Sarabia, L. A. & Ortiz, M. C. Response surface methodology. Compr. Chemom. 1, 345–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044452701-1.00083-1 (2009).

Ghafari, E., Costa, H. & Júlio, E. RSM-based model to predict the performance of self-compacting UHPC reinforced with hybrid steel micro-fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.064 (2014).

Cibilakshmi, G. & Jegan, J. A DOE approach to optimize the strength properties of concrete incorporated with different ratios of PVA fibre and nano-Fe2O3. Adv. Compos. Lett. 29, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633366X20913882 (2020).

Taşkın Çakıcı, G., Batır, G. G. & Yokuş, A. Preparation and characterization novel edible nanocomposite films based on sodium alginate and graphene Nanoplatelet, via Box–Behnken design. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-08057-4 (2023).

Bezerra, M. A., Santelli, R. E., Oliveira, E. P., Villar, L. S. & Escaleira, L. A. Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta 76 (5), 965–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2008.05.019 (2008).

Ghani, M. U. et al. Mechanical and environmental evaluation of PET plastic-graphene nano platelets concrete mixes for sustainable construction. Results Eng. 21, 10125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101825 (2024).

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Muhammad Umer** : Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. **Nawab Sameer Zada** : Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology. **Paul O. Awoyera** : Formal analysis; Data Curation; Visualization; Writing - Review & Editing. **Muhammad Basit Khan** : Methodology; Formal analysis; data curation; visualization; Writing - Review & Editing. **Wisal Ahmed** : Formal analysis; Data Curation; Visualization; Writing - Review & Editing. **Olaolu George Fadugba** : Formal analysis; data curation; visualization; Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Umer, M., Zada, N.S., Awoyera, P.O. et al. Synergistic effects and optimization of palm oil fuel ash and jute fiber in sustainable concrete. Sci Rep 16, 259 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27579-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27579-5