Abstract

Whereas the occurrence of oxic methane (CH₄) production (OMP) in the oxygenated water column of lakes is widely accepted, its mechanisms, isotopic signature, and contribution to total CH₄ emissions remain uncertain. Evidence suggests that phytoplankton produces CH4, but it is unclear how this pathway contributes to ecosystem OMP rates. Shallow lakes are often productive and feature high phytoplankton biomass, which could potentially lead to high OMP rates and a substantial contribution to CH4 emissions. Here we present results of a field mesocosm study carried out in three shallow lakes in the Pampean Plain (Argentina), designed to assess their ambient OMP dynamics. We combined this with laboratory experiments designed to estimate the potential CH4 production by phytoplankton strains from these systems. We demonstrate that OMP occurred in all lakes, albeit at low rates; all tested phytoplankton strains produced CH4, yet this production contributed up to 15% to OMP rates, implying that other pathways dominate the observed OMP. The contribution of OMP to lake CH4 diffusive emissions was low for all lakes and likely influenced by lake morphometry, suggesting that, despite their high phytoplankton abundances, other sources—such as sediment CH4 production and/or lateral inputs—dominate CH4 emissions in these ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The traditional understanding of methane (CH4) cycling in aquatic ecosystems considers that biological CH4 is solely produced under anoxic conditions by methanogenic archaea1. However, the frequent supersaturation of CH4 that is observed in oxic surface waters of aquatic ecosystems cannot be explained solely by transport of CH4 from anoxic sediments and deeper water layers2,3,4,5, generating what has been termed the “methane paradox”. Over the last decade there have been numerous reports of CH4 production in the oxic water column of aquatic ecosystems through various mechanisms, both under oxic and anoxic conditions6,7. These newly identified pathways of CH4 production are generically referred to as Oxic Methane Production (OMP), considering that they occur in oxygenated habitats, such as the oxic portion of the water column, but without necessarily implying that these specific pathways require oxygen to occur8. Collectively, these studies have demonstrated that there is no actual paradox but rather that the pathways of aquatic CH4 production are more diverse and complex than previously thought5,9.

There are several known metabolic pathways, in addition to archaeal methanogenesis, which produce CH4. There are reports of aerobic production of CH4 as a byproduct of methyl-phosphonates (MPn) decomposition by aerobic heterotrophs in marine2,10,11 and freshwater environments12,13,14. Similarly, aerobic demethylation of dimethyl sulfoniopropionate (DMSP) has been reported to produce methanethiol in marine waters, with the subsequent release of CH43. Aerobic metabolism of methylamine (MeA) has been also reported as a source of methane in lakes6,15 and it has even been hypothesized that all living cells can produce CH4 by a common mechanism triggered by free iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS)16. There is also growing evidence for a coupling between OMP and phytoplankton17,18. Grossart et al.4,19 detected methanogenic archaea in oxic waters of a lake in Germany, which were attached to phytoplankton and possibly living in micro-anoxic niches associated with algal cells. Moreover, several reports indicated a link between OMP and photosynthesis at an ecosystem scale20,21,22,23. In this regard, it has been experimentally shown that various phytoplanktonic groups including diatoms21, cyanobacteria24,25, chlorophytes22, cryptophytes22, haptophytes and marine microalgal species25,26,27 produce CH4, and that the rate of production is somehow linked to temperature and light exposure24,28. All of these results reflect that there appear to be multiple coexisting OMP pathways in freshwaters and these probably vary in relative importance among aquatic ecosystems, along trophic and other environmental gradients7,29,30. Regardless of the mechanisms behind OMP, there is still much uncertainty as to the magnitude of the rates of OMP at the ecosystem scale and the contribution of these pathways to freshwater CH4 emissions. There have been various attempts to address these questions, based on whole-lake22,29,31,32 or mesocosm20 mass balances, and also based on experimental incubations of lake water4,5,7,29,31. Reported ecosystem OMP rates vary from 0.01 µM day−1 up to 0.52 µM day−15,20,22,29,31,32. The studies that have quantified the contribution of OMP to total lake CH4 production, or to total lake CH4 emissions in the surface mixed layer of stratified lakes, have reported a wide range of values, from < 5% to up to ~ 80%29,31,32,33. This is in part related to core morphometric features of freshwater ecosystems, with the contribution of OMP increasing with decreasing sediment area to volume ratio31,32. Overall, as suggested by the contrasting results reported in the studies cited above, the factors that regulate OMP rates and the contribution of these pathways to total ecosystem CH4 emissions are still not well understood.

OMP pathways also contribute to the observed isotopic CH4 signature in the water column, and therefore to the processes that are inferred from these. The δ13C-CH4 in the water column and in the sediments has been used to assess the extent of CH4 oxidation, where the source has traditionally been assumed to be one of the two main anoxic methanogenic pathways which typically yield very depleted CH4 (− 65‰ to − 110‰34). There is increasing evidence that δ13C–CH4 generated by the various OMP pathways is highly variable (− 19‰ to − 63‰) but generally more enriched than δ13C–CH4 generated by archaeal methanogenesis25,30,32,35. Since OMP pathways generate enriched δ13C–CH4 that overlaps with the signature of oxidized methanogenic CH4, the existence of OMP complexifies CH4 isotopic mass balances, and it is therefore important to better assess CH4 lake dynamics.

OMP rates and their contribution to ecosystem CH4 emissions have been mostly explored in oligo- to mesotrophic lakes that tend to stratify, and there has been very little work done on shallow polymictic (that frequently mix) lakes23. These lakes tend to be productive and to develop high phytoplankton biomass36,37,38, and for this reason it could be expected that the rates of OMP might be high, yet the contribution of OMP to total CH4 diffusive fluxes may still be modest given the importance of sediments in these shallow systems. In addition, the phytoplankton communities of shallow lakes may be dominated by very different taxa39, which could potentially lead to differences in ambient OMP and in the potential values of δ13C–CH4 derived from OMP as well. To test these contrasting hypotheses, we present an integrative study that combines ecosystem, mesocosm and in vitro approaches to assess the magnitude and the ecosystem-level contribution of OMP, as well as the potential contribution of phytoplankton to this process, in three shallow lakes with different abundance and composition of phytoplanktonic communities. In situ mesocosm experiments were carried out in each lake to quantify field OMP rates and to assess the potential values of δ13C–CH4 derived from OMP. In addition, sampling of the lakes allowed extrapolation of the mesocosm results to determine the potential contribution of OMP to whole lake CH4 emissions. Finally, phytoplankton strains were isolated from each one of these lakes and used to carry out in vitro experiments to assess their potential CH4 production rates, which were subsequently used to infer the potential contribution of phytoplankton to ambient OMP in these lakes.

Methods

Study area

The Pampean Plain (35°32’–36°48’S; 57°47’–58°07’W) is a 600,000 km2 lowland in central Argentina. Its low slope, geomorphology, and climate create a hydrological system with diffuse catchments, poorly developed drainage, and shallow aquifers, leading to thousands of shallow lakes40. About 13,800 lakes exceed 10 ha, and 146,000 are between 0.05 ha and 10ha41. These lakes are shallow, polymictic (that frequently mix), and naturally eutrophic or hypereutrophic. Most are turbid-phytoplankton, with high algal biomass, turbidity, and absence of submerged macrophytes, while others remain clear-vegetated, with abundant macrophytes, lower algal biomass, and lower turbidity. Clear and turbid lakes usually show distinct phytoplankton community structures36,39,42.

Field experiments were carried out in three shallow Pampean lakes located in the province of Buenos Aires, where seasonal studies of their limnological conditions, phytoplankton structure and CO2 and CH4 emissions had been previously conducted36,43: La Salada (SA), El Burro (BU) and La Segunda (SG) (Fig. S1). SA and BU are phytoplankton-turbid, whereas SG is clear-vegetated. These lakes tend to present different phytoplankton abundance and community compositions, high CH4 emissions, and are located within an area of approximately 54 km2, so they shared similar climatic conditions during the study period.

Experimental design

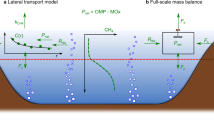

Field experiments were carried out in the 2021 austral summer, between 25th and 28th of January in SA; 29th of January and 2nd of February in SG; 2nd and 6th of February in BU In each lake, three (SA) or four (SG, BU) mesocosms were deployed (Fig. 1A, Fig. S2). Mesocosms were built with the same transparent polycarbonate sheets as in Bogard et al.20, which impedes the diffusion of gases (Suppl. Inf. 1). Mesocosms were 0.8 m deep, 1 m wide, with a volume of 628.3 L and a surface area of 0.8 m2. They were closed at the bottom to exclude sediments CH₄ production, were equipped with a floating device and protective rim to prevent lake water entry and were anchored to the sediment for stability. The average depth of the lakes at the time of the experiments was 1.2 m, 0.9 m and 0.9 m for SA, SG and BU, respectively. The enclosures were placed between 60 and 200 m from the shore of the lakes. Prior to the onset of the experiments, the enclosures were filled with water from 0.2 m below the surface of each lake using a submersible pump (Proactive Pump II, Waterspout 2, Proactive Environmental Products®) with a velocity of 11.12 L min-1. The water was run through a shower head device to equilibrate the dissolved gases with the atmosphere. The latter was done to lower the initial CH4 baseline (while retaining saturation of O2 and CO2) and therefore to facilitate the detection of changes in CH4 concentration within the mesocosms during the experimental period. In addition, water was filtered through a 55 µm pore size net to exclude large zooplankton that could graze on phytoplankton. The filling of the mesocosms did not cause sediment resuspension or alter phytoplankton morphology, as subsequently verified by the analysis of phytoplankton samples. After filling the mesocosms, high frequency oxygen (O2) and temperature (T) sensors (miniDO2T, Precision Measurement Engineering, Inc.®) were deployed inside each mesocosm as well as in the lake, in all cases at 0.4 m depth. These devices measured T (°C), O2 (mg L−1), and O2 saturation (%) every 5 min for the entire duration of the experiment. Note that in the clear lake submerged macrophytes were not included inside the mesocosms, since our study primarily focused on exploring CH4 production by the planktonic communities. The length of the experimental deployment varied slightly among lakes due to logistic considerations, including constraints imposed by COVID restrictions. To ensure consistency, here we present the results from the initial 100-h deployment for all experiments. After filling in the enclosures, a 24-h acclimatation followed, after which the limnological sampling was carried out. The only parameters sampled immediately after filling in the enclosures were the first point of dissolved CH4 and 13C-CH4. The detailed sampling design is shown in Table S1.

Overview of mesocosm field experiments and mass balance approach to estimate OMP rates. (A) Illustration of the field setup, indicating how the mesocosms were filled and where the O2/T sensors were located; (B) Mass balance components: the change in CH4 dissolved inside the enclosures between two consecutive time points (ΔCH4OBS) is the result of the potential CH4 produced through OMP (OMP) minus the CH4 oxidized (MOX) and the CH4 lost to the atmosphere through diffusion (EVA); (C) Mass balance solution example: the exampled modeled curve predicts the expected CH4 concentration in the mesocosms considering loss of CH4 through oxidation (MOX) and evasion (EVA), and compares this to the exampled observed curve (OBS). If the observed curve is higher than the modelled one, this implies existence of OMP, because the mesocosms are isolated from the sediment. The steps for this approach are: (1) estimating the remaining CH4 concentration at the end of the experiment by integrating CH4 concentration over time (which is done by multiplying the slope of the CH4 concentration vs time of each time segment, by the respective delta time) (Eq. 1.a), to calculate the difference between the initial CH4 mass and the total change in CH4 mass over the course of the experiment (Eq. 1.b); (2) obtaining the expected CH4 concentration in the mesocosms as the result of loss of CH4 by oxidation and diffusion was modeled using Eq. 2.a. The remaining modeled CH4 concentration at the end of the experiment was obtained as described before, using Eq. 1.a to obtain the change in CH4 in each time segment, and Eq. 2.b to obtain the final CH4 concentration; (3) subtraction of the remaining modeled CH4 concentration from the remaining observed CH4 concentration, divided by the time course of the experiment (Eq. 3a). A detailed description of the mass balance solution can be found in Section 6. Tree and bush symbols from Dylan Taillie and Jane Hawkey, respectively, and emergent macrophyte symbols from Tracey Saxby, Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Limnological characterization

In both mesocosms and lakes, T and O2 high-frequency sensors were supplemented with water T and O2 profiles measured at 10 cm intervals. An irradiance profile was carried out in the lakes, to assess the vertical attenuation coefficient for photosynthetically active radiation (Kdpar), and the euphotic depth was derived from this. Additionally, pH, turbidity, total suspended solids (TSS), total phosphorus (TP), total nitrogen (TN), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), chlorophyll a (Chla), and phytoplankton abundance and composition were analyzed both in the mesocosms and the lakes. Details of all these methods can be found in Suppl. Inf. 2. Archaeal and bacterial community compositions were analyzed in the lakes and mesocosms, as described in Suppl. Inf. 3. Ecosystem metabolism was calculated based on O2 dial variations, as specified in Suppl. Inf. 4. Atmospheric pressure, humidity and wind speed were recorded using a Kestrel 4000 Pocket Weather Tracker ® (Nielsen-Kellerman®).

Greenhouse gas analysis

Dissolved gas concentration and isotopic values

Dissolved CH4 and carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the water along with 13C–CH₄ and 13C–CO₂, were obtained by means of the headspace equilibration method44. Two 60 ml syringes were filled with 30 ml of water and 30 ml of atmospheric air, creating a 1:1 water: air ratio. Syringes were vigorously shaken for 2 min to allow equilibration of gases between water and air, and then the 30 ml of air were injected into 12 ml glass pre evacuated vials equipped with crimped rubber stoppers (Exetainer, Labco). Headspace samples were analyzed using a cavity ringdown spectrometer (CRDS) coupled with a Small Sample Isotopic Module (SSIM, Picarro G2201-i) to obtain the partial pressures (ppmv) and 13C values of CH4 and CO2. The original ambient partial pressure and isotopic values were obtained following Soued and Prairie45 and partial pressure (ppmv) was converted to concentration (µM) considering alkalinity, following Koschorreck et al.46. A more detailed description of the method can be found in Suppl. Inf. 5. Throughout the experimental course, dissolved CH4 and CO2 alongside 13C–CH₄ and 13C–CO₂ were measured in the lake and in each mesocosms five times in SG, six times in SA and seven times in BU (Table S2). Differences in the number of measurements respond to logistic considerations, including constraints imposed by COVID restrictions.

Diffusive fluxes

Diffusive flux of CH4 in the air–water interface was measured using an opaque floating chamber36,47 (extra information in Suppl. Inf. 6 and Fig. S3). The diffusive flux rates (fgas) were calculated in mmol m-2 d-1, following Eq. 1. Chamber measurements were inspected for bubble events based on whether there was an abrupt increase of CH4 or the pattern of CH4 increase over time was not following a strong linear relationship (R2 < 0.85). All chamber measurements were performed during the daytime.

where s is the accumulation rate of gas in the chamber (ppm min−1); V is the volume of the chamber (L); A is the chamber surface area covering the water (m2); mV is the molar volume of the gas at ambient temperature and pressure (L mmol−1); and t is a factor that converts minutes to days (1 day = 1440 min) 47.

Gas transfer velocity

Gas transfer velocities (K) were calculated based on floating chamber measurements of gas exchange carried out inside the mesocosms and in the lake43,47,48 (Eq. 2).

where Flux gas is the diffusive flux for CH4 obtained from Eq. 1 (mmol m−2 d−1), Kh is the Henry’s constant correspondent corrected for atmospheric pressure and water temperature, and ΔpGas is the difference between the partial pressure of the gas in the water (Pw) and the partial pressure of the gas in equilibrium with the atmosphere (Peq), i.e. ΔpGas (ppmv) = Pw − Peq.

The obtained values of K were standardized to a Schmidt number of 600 (Eq. 3), obtaining the standardized K600.

where Sc is the Schmidt number of a given gas at a given temperature75, and n is a value that depends on wind speed. We used a value of n = 2/3 for ambient wind speeds < 3.7 m s−1 and of n = 1/2 for ambient wind speeds > 3.7 m s−176. Wind speed in the enclosures was measured close to the protection rim.

Given that the mesocosms were well mixed (Fig. S4 and S5), K600 (m h−1) can be expressed as an evasion decay constant (KEVA, h−1) when divided by the depth of the mesocosm (0.8 m) and was used for the mesocosm CH4 mass balance calculations (see Section 6).

Methane oxidation (MOX) rates

To estimate CH4 oxidation (MOX) rates, dark incubations were carried out for each lake and for the mesocosms (scheme of the workflow and specific details in Fig. S6)20,49,50. Since MOX follows first order kinetics, the instantaneous CH4 oxidation rate (h-1) for each lake or mesocosm can be obtained as the slope of the regression between ln (dissolved CH4) (µM) vs Time (h)32,49. This estimate of oxidation decay constant (KMOX) was used for the mesocosm CH4 mass balances calculations (see Section 6 below).

Mesocosm mass balances

Given that the mesocosms were closed at the bottom, impermeable to gases and remained fully oxic during the entire length of the experiment (Fig. S5), any observed inputs of CH4 would have to originate from the mesocosm itself, and this would correspond to OMP occurring in the water column, since the short deployment time did not allow for significant phytoplankton wall growth development. Therefore, the change in CH4 concentration between two consecutive time points would be the result of the CH4 produced, minus the CH4 oxidized and diffused to the atmosphere20 (Eq. 4):

where \(\Delta {CH}_{4}\) is the change in CH4 concentration between two consecutive time points, \(OMP\) stands for oxic methane production rate, \(EVA\) reflects the rate of CH4 evasion to the atmosphere through diffusion, and \(MOX\) is the rate of CH4 oxidation. If there was no production of CH4 inside the mesocosms (OMP = 0), the concentration of CH4 inside the enclosures would continuously decline to eventually equilibrate with the atmosphere, at a time frame that is dependent on the initial CH4 concentration and the total CH4 loss rate \(\left(EVA+MOX\right)\). Following this reasoning, CH4 concentrations above what would be expected based on the total CH4 loss would necessarily be due to OMP inputs.

The OMP component from Eq. 4 cannot be directly measured, but it can be indirectly derived from the rest of the components of the mass balance: CH4 concentration was measured in the mesocosms at each time point; the evasion rate was measured with floating chambers (Section “Diffusive fluxes”); and the MOX rate was estimated in dark incubations (“Methane oxidation (MOX) rates”). The empirical dissolved CH4 data obtained at each time point allows us to build an empirical curve describing the behavior of CH4 through time. This observed curve can be further compared to the theoretical curve that predicts the expected CH4 concentration in the mesocosm at each time point resulting from CH4 loss due to oxidation and evasion (Eq. 5). This theoretical curve was calculated based on the Keva from the diffusive flux data (Section “Gas transfer velocity”), and the Koxi estimated from experimentally derived MOX data (Section “Methane oxidation (MOX) rates”). If the observed curve is higher than the theoretical curve modeled based on CH4 loss both from oxidation and evasion (Eq. 5), this implies an excess of CH4 relative to the expected concentration, indicating input from OMP.

where [CH4]t corresponds to the modeled concentration of CH4 at a given time point (t, in µM), [CH4]t0 corresponds to the concentration of CH4 at time zero of the mesocosm experiment (t0, µM), KMOX corresponds to the decay constant of MOX (h−1) obtained from the dark incubations, t corresponds to a given time (h) and KEVA corresponds to the decay constant of evasion (h−1) obtained from the floating chamber measurements.

To solve the mass balance proposed in Eq. 4 we used an approach based on integrating the change in the mass of CH4 between consecutive time points for each mesocosm and for the entire length of the experiment (Fig. 1C), both for the observed concentrations (Fig. 1C panel 1), and the modeled concentrations based on Eq. 5 (Fig. 1C, panel 2), an extension of the mesocosm-based approach applied by Bogard et al.20. We should point out that CH4 concentrations declined in all mesocosms through time, so the approach described above involved reconstructing the patterns of loss in observed and predicted CH4 concentrations, and comparing the resulting remaining masses of CH4 to derive potential OMP rates in each mesocosm (Fig. 1C, panel 3). Positive differences between these final remaining masses represent the mass of CH4 produced through OMP, and all the mesocosms yielded overall positive estimates.

Although the water used for the mesocosms was degassed through a shower head device during filling, the initial mesocosm CH4 concentrations differed greatly (by orders of magnitude) between mesocosms of the different lakes, reflecting the vastly different ambient lake concentrations at the time. Given that we are modeling CH4 losses as first order processes, which depend on initial CH4 concentrations, we standardized the observed and modeled CH4 concentrations in each mesocosm to their respective initial concentration to remove potential biases induced by large differences in initial ambient concentrations and thus render comparable OMP rates. Using these standardized concentrations (unitless), we derived OMP rates following the scheme presented in Fig. 1C, which yielded OMP rates in units of time−1 rather than as µM time−1. In Fig. S7 we present the observed concentrations as a function of time for each mesocosm, that are the basis for these calculations.

The uncertainty around the modeled curves (MOX, EVA, and MOX + EVA) was estimated using Monte Carlo simulations. These simulations incorporated the variability in the model parameters, which were the mean and standard deviation of KMOX and KEVA specific to each lake, and the mean and standard deviation of the standardized initial CH4 concentration for each mesocosm. For each of the 10,000 simulations, random parameter values were sampled from normal distribution curves defined by these means and standard deviations, and the model was repeatedly evaluated over the range of time points. The resulting ensemble of model outputs was then used to calculate the mean predicted curve and its associated uncertainty.

OMP contribution to total lake CH4 diffusive flux (OMC)

To estimate the contribution of OMP to total lake CH4 emissions, we compared the standardized OMP rates (day−1) determined in the mesocosms to the standardized CH4 diffusive fluxes from the lakes (day−1) (Eq. 6). CH4 diffusive fluxes from the lakes were standardized to the CH4 concentration in the lake at the moment of the diffusive flux measurement, and to the area and volume of the lake. The surface area of the lake is known from studies done previously in area36 and the volume was obtained as the mean depth (m) multiplied by the surface area (m2), a good estimation for these types of shallow systems which are pan-shaped and have a relatively uniform depth77.

where \(OMC\) is the contribution of OMP to lake CH4 emissions (%), standardized \(OMP\) is the standardized aerobic CH4 production measured in the mesocosms (d−1) and \(standardized lake Flux\) is the standardized CH4 diffusive flux measured in the respective lake (d−1). OMC was calculated for each measured CH4 diffusive flux in each lake.

Mesocosm isotopic mass balances

To calculate 13C values of CH4 potentially associated with oxic production, (δ13C–CH4-OMP), a two-step isotopic mass balance was carried out. First, the measured 13C–CH4 in the mesocosmos was corrected to remove the effect of fractionation due to evasion and oxidation. The fractionation factor of evasion (αeva), a value of 1.0008, was obtained from the literature51. The fractionation factor of oxidation (αox) was calculated using data from our own dark incubations. The slope from the regression between ln [CH4] vs ln (13C–CH4 + 1000) was used to obtain αox using Eq. 7.

Subsequently, 13C–CH4 was corrected for evasion and oxidation using Eq. 8.

where \({\delta^{13} CH}_{4 corr}\) corresponds to the 13C-CH4 corrected by evasion and oxidation, \(Evasion\) corresponds to the expected rate of EVA (µM hr−1) for each enclosure and each time point, which was obtained from the modeled curve considering only loss of CH4 through evasion. \(MOX\) correspond to the expected rate of MOX (µM hr−1) for each enclosure and time point, which was obtained from the modeled curve considering only loss of CH4 through oxidation. \({{\delta }^{13}{CH}^{4}}_{ ambient}\) corresponds to the 13C–CH4 of measured CH4 in the water column of the mesocosm, \({\alpha }_{eva}\) and \({\alpha }_{mox}\) are the fractionation factors, both in delta form (‰), obtained as (\(\left(\alpha -1\right)*1000\))32.

\({\delta^{13} CH}_{4 corr}\) was further used along with the 13C–CH4 of the water used to fill the mesocosms at the onset of the experiment to derive the δ13C–CH4-OMP following Eq. 9.

where \(\delta ^{{13}} CH_{{4~OMP}}\) is the 13C of CH4 produced through OMP, \({CH}_{4 zero}\) and \({\delta CH}_{4 zero}\) are the concentration (µM) and the 13C-CH4 of the water used to fill the mesocosm, respectively; \({CH}_{4 Tx}\) is the concentration of CH4 (µM) at any given time point and \({\delta^{13} CH}_{4 corr Tx}\) is the 13C–CH4 at that given time point, which was previously corrected for fractionation due to evasion and oxidation. We estimated \({\delta CH}_{4 OMP}\) for each time point of the experimental mesocosm time course (five time points for SG, six time points for SA and seven time points for BU), and here we report the average value for the entire experiment.

Phytoplankton cultures

To assess the potential for CH4 production by phytoplankton present in the study lakes, phytoplankton species were isolated from each one of the three lakes. Water from SA, SG and BU was collected and filtered through a 55 µm net to exclude macro and mesozooplankton, on the 5th of May 2022. The water was transported to the laboratory, where it was inoculated in petri dishes78 with agar mediums BG1152, Bold’s Basal Medium53 (BBM), BBM + Vitamins (cyanocobalamin, thiamine and biotin) and BBM + soil extract (3:1, v/v), in all cases using the spray technique54. Three petri dishes per medium and lake were inoculated, obtaining a total of 48 inoculated plates. These were kept under controlled conditions of light (photoperiod 12:12 light: darkness) and temperature (25 °C). Weekly identification of growing colonies was done using a dissection microscope (Nikon SMZ 745 T, 5 × to 50 ×). When a colony was detected, it was removed from the petri dish under sterile conditions, observed in an optical microscope (Olympus BX50, using 400 × and 1000 ×) to identify the genera using specific bibliography55,56,57 and later inoculated in another petri dish with the same growth medium for further isolation, establishing non axenic unialgal stock cultures. Further experiments were carried out with active liquid cultures developed from the petri dish cultures, using the same culture media. Although it was not possible to isolate all the dominant genera present in these shallow lakes, further experiments were carried out including 4 genera of chlorophytes and 3 genera of cyanobacteria that were prevalent in the lakes and that are in general representative of Pampean shallow lakes39,58.

Experiments to measure methane production by algal strains using membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS)

Experiments were carried out to assess the potential production of CH4 by the phytoplankton isolates using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (MIMS, Bay-Instruments, Fig. S8)24. Each culture was placed in a 3.5-ml glass chamber that was surrounded by an acrylic jacket connected to a recirculating water bath used to maintain the culture at a constant temperature of 25 °C. The culture chamber was located above a stirrer, to ensure mixing and to avoid gradients, and it was exposed to a photoperiod of 15 h light: 9 h darkness (similar to the photoperiod in summer in Argentina), at a light intensity of 120 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The culture chamber had an inlet and an outlet, and the culture fluid was continually circulated through the MIMS exchanger by means of a small peristaltic pump. O2 and CH4 in the culture were measured every 12 s, and only one culture at a time could be processed. The extent of MIMS physical loss depends on CH4 concentration within each culture: to characterize this physical CH4 loss, autoclaved cultures were employed to establish a connection between the initial CH4 concentration in a culture and the rate of physical CH4 loss through the MIMS. Since these were dead cultures, they lack biological fluctuations in CH4 concentration and solely exhibit CH4 loss due to physical factors. Leveraging this dataset, a linear relationship between the initial CH4 concentration and the rate of physical loss was derived. This correlation was subsequently used to estimate the physical loss for each measured culture, considering their initial CH4 concentration (Fig. S9). Each experiment lasted between three to five days, and two to three experiments were carried out for each culture: at least one measurement of live cultures and, for most strains, one measurement of the autoclaved (dead) culture. As negative controls, ultrapure water and sterile BG11 culture media were used. Differences in CH₄ production rates between Chlorophyte and Cyanobacterial strains were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with Group (Chlorophytes vs. Cyanobacteria) as a fixed factor and Strain as a random factor, using package lmerTest 3.1–259. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested using package Car 3.0–860. Tests were performed at the 95% significance level using R version 3.6.2 in the RStudio environment version 1.2.5019.

At the beginning and end of each experiment, chlorophyll a (Chla) was measured, and ambient DNA was extracted from the culture (Suppl. Inf. 8). Chla measurements were done to standardize phytoplankton-derived methane production rates to biomass, whereas DNA extraction followed by PCR was carried out to test for the presence of methanogenic archaea and methanotrophic bacteria.

Phytoplankton methane production rates and contribution to field OMP rates

Phytoplankton methane production rates were calculated using the Stavisky-Golay function from the Signal package in R (http://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/signal/)24. First, CH4 concentration vs time interval curves were smoothed using the sgolay function, fitting a polynomial of second degree and no derivative. The sgolay function was then used to obtain the first derivative of this smoothed curve—which corresponds to the rate—also fitting a second-degree polynomial. The rate thus obtained was then corrected for the rate of physical loss of gas from the experimental setup (derived as described above) and was standardized to the Chla concentration of each culture, obtaining rates in units of µmol CH4 hr−1 gr Chla−1.

The potential contribution of phytoplankton CH4 production to field OMP rates was estimated by scaling the estimated CH4 production of each strain to the mean Chla concentration in the mesocosms of each lake, and then relativized for the mean CH4 dissolved concentration (µmol L−1) in the mesocosms at the end of the experiments, obtaining a value in day−1, that was afterwards compared to the mean estimated standardized OMP rate (day−1) in each lake. It was decided to do this upscaling exercise for each strain separately, assuming that the enclosures would be fully dominated by one of those strains in each case, to explore how the different rates would affect the contribution. It was also decided to relativize the phytoplankton CH4 production rates for the mean CH4 dissolved concentration in the enclosures at the end of the experiment because, according to our calculations, at that point the CH4 dissolved remaining in the enclosures is attributable to OMP, whereas at the beginning of the experiments there is CH4 being lost by oxidation and evasion to the atmosphere, which would underestimate the contribution.

Results

Limnological characteristics

Mesocosms of SG had a higher transparency, lower total phosphorus (TP), total nitrogen (TN), total suspended solids (TSS) and phytoplankton abundance than the mesocosms of SA and BU (Table 1). Compared to SA, the mesocosms in BU had higher levels of turbidity and TSS. The mesocosms in SA had a higher Chla than the mesocosms of BU. The BU mesocosms were dominated by smaller phytoplankton species that occurred at a higher abundance, whereas the SA mesocosms had the opposite pattern, with larger phytoplankton species dominating. Concentrations of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), dissolved O2, and O2 saturation levels were generally high and comparable across the mesocosms of all three lakes. Based on the diel variability on O2, the mesocosms from SG were on average net heterotrophic, whereas the mesocosms from SA and BU were on average net autotrophic. All the studied lakes were on average net autotrophic. The difference in GPP and RE between mesocosm and lake of SG is related to the presence of submerged macrophytes in the lake, but the absence of them in the mesocosm. The difference in GPP between the mesocosms and lake of SA and BU are likely related to the slight differences in the abundance of primary producers.

The water temperature, (water T), pH, O2 concentration and saturation, and dissolved CH4 were measured at each time point (five time points in SG, six time points in SA and seven time points in BU). Turbidity, TSS, Kdpar, euphotic depth, DOC, DIC, TP, TN, Chla, phytoplankton abundance and composition were assessed at the beginning and end of each experiment (two time points). T of the water, dissolved O2 and O2 saturation correspond to sub superficial values. NA means there is no data. Secchi depth was not registered in lake SG because the submerged macrophytes do not allow a comparable measurement. GPP (gross primary production), ER (ecosystem respiration) and NEP (net ecosystem production) were calculated based on diurnal O2 variations obtained from the high frequency data loggers: for the lakes the informed value corresponds to the daily mean for the one miniDOT located in the lake, whereas for the mesocosms the reported value represents the daily mean of the miniDOTs deployed inside replicate mesocosms.

Phytoplankton community composition differed between the three lakes but was similar between the lake and the corresponding mesocosms (Fig. S10). In SG the dominant genera were Chlamydomonas sp. and Didymocystis sp. (Chlorophyta), Cryptomonas sp. (Cryptophyta) and Coelosphaerium sp. (Cyanobacteria). In SA, there was an almost complete dominance of Scenedesmus linearis (Chlorophyta) (52–68% of the total phytoplankton abundance) followed by Oocystis sp., Eutetramorus sp. and Cosmarium sp. (Chlorophyta). In BU, the dominant genera were Monoraphidium sp, Oocystis sp., and Scenedesmus sp. (Chlorophyta), and Planktolyngbya sp., Geitlerinema sp. and Anabaenopsis sp. (Cyanobacteria).

Methanogenic archaea were detected in water samples of all three lakes and their respective mesocosms (Fig. S11a). The class Methanomicrobia was the most widespread methanogenic group and was detected in all three lakes and their mesocosms, whereas the class Methanobacteria was only detected in the lake and mesocosms of SG. Methanotrophic bacteria were also detected in water samples of all three lakes and their respective mesocosms (Fig. S11b). Methanotrophs from the class Gammaproteobacteria were detected and most abundant in all lakes and mesocosms, whereas methanotrophs from the class Aphaproteobacteria was detected in mesocosms and lakes in BU and SA, but in SG only in the mesocosms at the end of the experiment.

CH4 dynamics in lakes and experimental mesocosms

Patterns in dissolved CH4 and δ13C–CH4

The lakes differed greatly in ambient surface water CH4 concentration at the time of mesocosms deployment, with average concentrations of 122.8 ± 10.9 µM, 1.5 ± 0.2 µM and 0.3 ± 0.1 µM for SG, SA and BU, respectively (Fig. S12 a, c and e). CH4 concentrations in the mesocosms were consistently lower than in the surrounding lake, suggesting partial degassing during filling. The initial CH4 concentration in the mesocosms at the onset of the experiments nevertheless differed by orders of magnitude between lakes, still reflecting ambient lake differences: 65.1 ± 5.7 µM, 0.9 ± 0.1 µM and 0.1 ± 0.0 µM for SG, SA and BU, respectively (Fig. S12 b, d and f). CH4 concentrations subsequently declined in all mesocosms during the experimental time course, whereas in lakes the dynamics of surface water CH4 followed different patterns (Fig. S12 a–f). The mean CH4 concentration in the mesocosms was 40.32 ± 6.30 µM, 0.42 ± 0.06 µM and 0.04 ± 0.01 µM for SG, SA and BU, respectively, whereas for the lake was 50.6 ± 45.5 µM, 1.5 ± 0.3 µM and 0.3 ± 0.1 µM for SG, SA and BU, respectively. The isotopic composition of ambient CH4 (13C-CH4) generally ranged between − 20 ‰ and − 40 ‰ in both the lake and the mesocosms (Fig. S12 g–l), except for a period of very depleted CH4 that occurred in BU mesocosms between 45 and 75 h (up to − 60 ‰).

CH4 exchange velocity and diffusive fluxes

Diffusive CH4 fluxes were higher in the lakes than in the mesocosms (Fig. S13a), which is expected given that the lakes had both higher ambient CH4 concentrations and higher exchange velocities (Fig. S13b). The mean CH4 diffusive fluxes from the lakes were 24.7 ± 13.5 mmol m−2 d−1, 21.6 ± 19.5 mmol m−2 d−1, and 0.5 ± 0.1 mmol m−2 d−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively, whereas the mean fluxes in the mesocosms were 0.6 ± 0.4 mmol m−2 d−1, 0.2 ± 0.1 mmol m−2 d−1 and 0.02 ± 0.00 mmol m−2 d−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively. Similarly, gas exchange velocities were consistently higher in the lakes than in the mesocosms (Fig. S13b), likely because mesocosms are sheltered from the wind due to the protective rim on the side and reduced overall turbulence. The mean K600 CH4 for the lake were 0.7 ± 0.1 m d−1, 2.0 ± 0.2 m d−1, and 1.6 ± 0.5 m d−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively, whereas the mean K600 CH4 for the mesocosms were 0.1 ± 0.0 m d−1, 1.2 ± 0.4 m d−1 and 0.6 ± NA m d−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively. The estimated Keva were 0.01 h−1, 0.06 h−1 and 0.03 h−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively.

Methane oxidation (MOX) rates

We observed a general decrease in CH4 concentrations and a concomitant enrichment of δ13C-CH4 in the dark in vitro incubations, in some cases also coupled with an increase in CO2 concentration, suggestive of CH4 oxidation (Fig. S14). The estimated CH4 oxidation decay constants (KMOX) averaged 0.03 h−1, 0.01 h−1 and 0.02 h−1, for SG, SA and BU, respectively (Fig. S15).

Estimates of OMP rates and isotopic signature of CH4 derived from oxic production (δ13C–CH4-OMP)

OMP rates and OMC

At almost every time point in all mesocosms (except 21 h in BU) the observed CH4 concentration exceeded the modeled CH4 concentration based on the combination of MOX + EVA, suggesting CH4 production in all the mesocosms throughout the experiments (Fig. 2). A plot indicating MOX and EVA curves separately can be found in Fig. S16. The estimated (standardized) OMP rates in the mesocosms of each lake, derived as described in Section 6 of methods, were 0.01 ± 0.00 day−1, 0.07 ± 0.01 day−1, and 0.07 ± 0.01 day−1 for SG, SA and BU, respectively (Table 2). A table with the absolute rates can also be found in Table S3.

Observed (blue) and theoretical curve (yellow), the latter indicating the expected CH4 concentration in the mesocosms assuming no OMP and loss of CH4 by oxidation (MOX) and evasion to the atmosphere (EVA) for SG (a), SA (c) and BU (e). Decay constants of evasion (KEVA) and oxidation (KMOX) for SG (b), SA (d) and BU (f).

The contribution of OMP to total lake CH4 diffusive flux (OMC) ranged between 0.3 and 6.7% depending on the lake (Table 2).

Isotopic signature of CH4 derived from oxic production (δ13C-CH4-OMP)

We used an isotopic mass balance approach to derive the potential isotopic signature of CH4 produced under oxic conditions in the mesocosms. For this mass balance, fractionation factors for CH4 oxidation (αoxi) were derived from the in vitro MOX dark incubations, and were estimated at 1.02, 1.03 and 1.21 for SA, SG and BU, respectively (Fig. S17). αoxi for BU was too high and the R2 of this regression (0.83) was weaker than that of the regression for SA (0.99) and SG (0.99). This was presumably related to the fact that in BU CH4 concentration was very low, which made it difficult to measure13C–CH4 precisely. Accordingly, we assumed that the αoxi of BU = SA, since both are turbid phytoplankton-dominated lakes. The estimated 13C–CH4 OMP for the mesocosms was consistently enriched relative to the isotopic values of CH4 produced in the surrounding sediments (− 62.21 ± 0.14 to − 59. 81 ± 1.11, unpublished data from these lakes). δ13C–CH4-OMP for SA and BU were similar, whereas SG had a more depleted value (Table 2).

The different water colours are related to the abundance of phytoplankton in each shallow lake, which increases from SG to SA and BU.

In vitro experiments to assess phytoplankton CH4 production

Four Chlorophyte (Scenedesmus linearis, Scenedesmus quadricauda, Monoraphidium circinale, Oocystis lacustris) and three Cyanobacteria (Phormidium sp., Leptolyngbya sp., Pseudanabaena sp.) strains isolated from the three studied lakes were tested for potential CH4 production with a protocol using MIMS. As controls, Mili-Q water (Fig. S18a) and BG11 medium (Fig. S18b) were used, all of them being equilibrated with sterile-filtered air before measurement in the MIMS. Milli-Q water did not show any changes in CH4 concentration through time, as expected. Likely because the BG11 medium was not sufficiently equilibrated, there was initially a slight decrease in CH4 and O2 concentrations. All tested cultures were alive and had a clear and recurrent diurnal pattern of photosynthesis and respiration as reflected in variations in O2 concentrations (Fig. S19). The results from two cultures, Leptolyngbya sp. and Oocystis sp. are shown as examples (Fig. 3). All tested cultures showed increases in CH4 concentration during light hours, followed by decreases during the dark, and there was an overall coherence between the diurnal patterns in O2 and those of CH4 (Fig. S19). No methanogenic archaea nor methanotrophic bacteria were detected in any of the phytoplankton cultures (Fig. S20). This implies that the observed increases of CH4 in light conditions can only be attributed to phytoplankton and related to photosynthesis, since there are no other methanogenic organisms present in the culture. On the other hand, the decrease in CH4 during dark hours must be related to the physical CH4 loss from the system that offset the decrease in CH4 production in the dark, since there was no apparent biological CH4 consumption in the cultures. From the diurnal variations in CH4 concentrations we were able to derive CH4 production rates for each of the cultures over several diurnal cycles, and Table 3 shows the mean CH4 production rate for each culture for the ensemble of incubations that were carried out for each culture. These rates represent the mean CH4 production per g of Chla and per hour of a 24-h cycle. CH4 production rates ranged between 0.02 to 0.20 µmol CH4 g Chla−1 h−1, and no significant differences between Chlorophyta and Cyanobacteria were detected (F (1,4) = 0.7, p = 0.5), although within each group there were some variations in production rates.

Dissolved CH4 and O2 in the culture and derived phytoplankton CH4 production daily mean rates, for one of the measurements of Leptolyngbya sp. (A) and Oocystis sp. (B). Yellow columns correspond to hours of light and grey columns correspond to hours of dark. Picture of Leptolyngbya sp. taken from Culture Collection, picture from Oocystis sp. taken from AlgaeBase.

Discussion

We detected OMP in all mesocosms, albeit at very different rates. Mean standardized OMP rates (Table 2, SG 0.01 day−1, SA 0.07 day−1 and BU 0.07 day−1) were obtained using standardized CH4 concentrations, as explained in the methods section, in units of day-1. The isotopic mass balances revealed an isotopic signature for the CH4 produced through OMP that was much more enriched (~ − 38‰ to − 52‰) than the CH4 produced in the sediment, and more similar to the one of oxidized CH4. There are not many studies that have explored the potential isotopic signature of the CH4 produced through OMP, but the few studies that have done so have also reported enriched signatures for the OMP-CH4. Using isotopic whole-lake mass balances, Thottathil et al.32 reported δ13C–CH4 OMP values for four Canadian lakes (− 38.0 ± 1.4‰ to − 63.6 ± 2.2‰) that were also greatly enriched relative to anoxic sediment sources. In line with this, Klintzsch et al.25 explored the isotopic values of CH4 produced directly by different cultures of marine phytoplankton species, which ranged from − 19.3 ± 0.9 ‰ to − 54.5 ± 1.6 ‰, implying a uniquely enriched signature for phytoplankton-derived CH4. Similarly, Hartmann et al.22 reported enriched values for cultures of several freshwater phytoplankton species (~ -42‰ to − 50‰). Taenzer et al.35 carried out marine water incubations and reported a MPn-derived δ13C–CH4 of − 40 ± 5‰, indicating also an enriched δ13C–CH4 for MPn derived CH4. Ours and the above cited results imply that the observed isotopic signature of CH4 in the water column of freshwater ecosystems it is not just the results of the pathway by which CH4 was produced in the sediments (acetoclastic or hydrogenotrophic pathways) and the extent of oxidation in the water column, but it also includes the signature from diverse OMP sources, that add CH4 in the water column with a signature similar to that of oxidized CH4. This makes MOX mass balances derived from isotopes more complex than previously thought, because the observed isotopic signature of dissolved CH4 in the water column also includes the confounding influence of OMP.

Estimating OMP rates at an ecosystem scale is extremely challenging, because it involves the quantification of several different processes with high spatio-temporal dynamics that cannot be directly measured and therefore must be derived from other measurable processes, usually through a mass balance. The mesocosm approach greatly simplifies this mass balance approach by excluding sediment CH₄ production, CH₄ bubble dissolution, and lateral transport, allowing us to focus on two components that can be readily measured, CH₄ oxidation (MOX) and CH₄ emission to the atmosphere (EVA), and to derive OMP by difference. At the same time, mesocosms may generate physical and limnological conditions that differ from those of the surrounding lake, yet the factors that are key to OMP, such as nutrients, Chla and DOC remained roughly comparable between mesocosms and lakes throughout the experiments (Table 1). Nevertheless, quantifying CH4 oxidation and CH4 diffusive flux to the atmosphere posed a challenge. We estimated MOX using dark incubations, as was done by Bogard et al. 20 and Thottathil et al. 32. We are aware, however, that MOX rates are affected by CH4 concentration, O2 concentration and potentially by light irradiance, where the latter seems to result in MOX inhibition61,62,63 (but also see64,65). CH4 and O2 concentrations were roughly similar between the incubations and the mesocosms, but light irradiance was higher in the latter. Therefore, dark incubations could have led to an overestimation of MOX rates, which translates into an overestimation of OMP rates from the mass balance. Conversely, potential OMP from methylated substrates was not excluded from MOX incubations, which would result in an underestimation of MOX and therefore an underestimation of OMP rates from the mass balance. We are confident, however, that our oxidation data are sound overall (Figures S14 and S15) and that MOX rates are coherent with values reported for other lakes29,31,32. Regarding CH₄ diffusive fluxes, repeated measurements were taken in all mesocosms and lakes. We acknowledge, however, that diffusive fluxes were measured only in the daytime, which may introduce bias. Some studies report higher daytime CH₄ fluxes than at night66,67, others report lower values68,69,70, yet others find no significant diel differences71. Consequently, our daytime measurements could have either over- or underestimated true daily fluxes, and therefore OMP rates. Because CH4 diffusive emissions can vary significantly with weather conditions, we minimized this variability by carrying out mass balances using average gas exchange velocities and wind speeds.

When compared to other standardized OMP rates reported in the literature, which for the most part had much lower chlorophyll concentrations, our lakes were on the lower end (Fig. S21). Despite being eutrophic to hypertrophic, these shallow lakes had OMP rates that were either within the range, or lower than what has been reported for lakes with much lower chlorophyll concentrations (Fig. S21). Previous studies had shown a relationship between chlorophyll concentration and OMP rates across a relatively narrow range of oligotrophic to mesotrophic temperate lakes20,32, but these shallow, highly productive Pampean lakes do not fit this pattern at all. This suggests that chlorophyll is not a universal scaling variable for OMP across lakes, and that factors other than the phytoplankton biomass may drive OMP in lakes of different types7,23,29,30,72.

In this regard, our own experimental results confirmed production of CH4 by all the tested phytoplankton strains. In all cases, CH4 production appeared to be linked to photosynthesis based on the coherence in the diurnal patterns of O2 and CH4, as had been described before24. It can be noted that, even though there was a general trend of increased CH4 after an increase in O2, the specific alignment or lagging between these curves had different daily patterns depending on the strain. Further exploration on these daily patterns exceeds the scope of the study and require further analysis into the specific mechanisms behind CH4 production by phytoplankton. We observed CH4 production from both Cyanobacteria and Chlorophyta genera, with CH4 production rates ranging between 0.02 and 0.2 µmol CH4 g Chla−1 h−1. Our results add to the increasing body of evidence of widespread CH4 production across major marine and freshwater phytoplankton groups21,24,25,26,27. Our measured phytoplankton production rates were higher than those reported by Gunthel et al.21 for a range of freshwater diatom strains (~ 0.004 µmol CH4 g Chla-1 h−1), but more similar to those reported by Bižić et al.24 for cyanobacterial strains (~ 0.03–0.004 µmol CH4 g Chla−1 h−1) (assuming that approximately half of the dry weight is carbon, and that the Chla to carbon ratio ranges from 1:20 to 1:60 80,81). We observed one order of magnitude range in CH4 production among the strains tested but this range was not linked to light or nutrient availability since experimental conditions were similar for all strains, and there was not a clear difference in CH4 production rates between major phytoplankton groups. There are probably intrinsic differences in metabolic pathways and growth responses between strains that shape these patterns of phytoplankton CH4 production that require further exploration. Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, these experimentally derived rates can be extrapolated to the mesocosm field conditions to derive a first order estimate of the potential contribution of phytoplankton to ambient OMP. Our results suggest that the production of CH4 by phytoplankton is likely to have a small contribution (maximum potential scenarios reached up to 15.9 ± 8.1%) of the estimated ambient OMP in all the mesocosms, despite the high algal biomass and chlorophyll concentration that characterized mostly SA and BU. Studies have reported a positive influence of light exposure and intensity on phytoplankton CH4 production under controlled conditions21,24,28. In this regard, the growth media and light conditions used in the CH4 production essays do not mimic the ambient conditions that these phytoplankton strains experience in situ. Similarly, every isolation technique has its own biases and may generate potentially different growth conditions. However, there is no reason to think that the above-mentioned differences would lead to strains expressing CH4 production rates that would be orders of magnitude higher in situ than in culture. All the evidence points to the fact that whereas the major phytoplankton groups in these shallow lakes do produce CH4, these phytoplankton-linked CH4 production rates account for only a small proportion of the observed OMP. This may explain the observed uncoupling between the estimated OMP and the ambient chlorophyll in these systems (Fig. S21).

CH4 production as a by-product of MPn degradation in the process of phosphorus acquisition by bacteria is a widely known source of oxic CH4 production in P-stressed waters2,10. In the presence of phosphate, however, MPn degradation activity of bacteria can be repressed12. Shallow Pampean lakes have high concentrations of phosphorus and, therefore, degradation of MPn is not expected to be a substantial CH4 source, although this pathway cannot be discarded. Grossart et al. 4 also reported that methanogenic archaea could attach to phytoplankton, possibly living in micro-anoxic niches, and this implies that they could potentially produce CH4 through anaerobic methanogenesis but in the water column. Analysis of DNA from the water revealed the presence of 16S rRNA gene sequences of methanogens in all the mesocosms from the three shallow lakes. While this is no measure of methanogenic activity, we cannot exclude that archaea may have contributed to methane production in the mesocosms. In this regard, studies have further suggested a link between OMP and ambient primary production20,31, assumed to reflect direct photosynthesis-related algal CH4 production, but which may reflect the enhancement of other OMP pathways, including algal-associated archaeal methanogenesis. If such a connection exists, our results suggest that it is not scalable across systems, since our mesocosms had comparable OMP to those reported in oligotrophic and mesotrophic sites yet primary production rates were several folds higher than in those oligotrophic systems. In addition, methane production through photooxidation of organic matter73,74 has also been reported as a source of OMP, although the predominant product seems to be CO2 rather than CH479. These shallow lakes had high light irradiances during the experiments, implying that this pathway could contribute to OMP but, if it was the case, this would probably occur in a slight proportion. Another potential source reported as explanation for OMP is bacterial degradation of dissolved organic matter (DOC)10. The three shallow lakes from this study exhibited high concentrations of DOC suggesting that this pathway could potentially also contribute to the observed OMP rates.

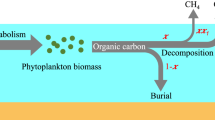

Our results imply that OMP is not the dominant pathway fueling overall CH4 diffusive emissions measured in these lakes, despite being eutrophic and highly productive. Previous studies have suggested that lake morphometry plays a role in determining the contribution of OMP to total CH4 production or emission, in particular, the ratio of sediment area (Ased) to mixed layer volume (V)31,32. The results from these shallow lakes are in good agreement with the patterns found in lakes elsewhere, and extend the reported patterns to a much wider range of values of Ased/V (Fig. 4). This pattern suggests that CH4 dynamics in these shallow lakes are dominated by other processes, such as sediment CH4 production and/or lateral transport from the catchment, regardless of phytoplankton biomass and ecosystem metabolism. Deep lakes fall into the other extreme, where the water column is largely uncoupled from sediments, and where OMP plays a major role in determining CH4 emissions, even when OMP rates may be low.

Relationship between oxic methane contribution (OMC) and lake morphometry, specifically, the ratio of sediment area (Ased) to mixed later water column volume (V). For these shallow and polymictic lakes, the entire lake volume is considered as V. The colours represent different studies, and the data in purple dots correspond to this study. “Estimations_Gunthel et al.21” refers to the estimations reported in that study for lakes other than those specifically studied, which are included as “Gunthel et al.21”.

In summary, through field mesocosm experiments we were able to estimate ambient OMP rates and the potential contribution of this pathway to total CH4 fluxes in three shallow lakes that differed in algal biomass and productivity. Furthermore, by means of controlled experiments we were also able to infer the potential contribution of phytoplankton to estimated OMP rates (Fig. 5). We have shown that OMP rates in these eutrophic lakes were comparable to those reported in oligotrophic and mesotrophic lakes despite large differences in phytoplankton biomass and primary production. The contribution of OMP to CH4 diffusive emissions (OMC) was modest (< 15%), suggesting that in these shallow lakes, other sources dominate CH4 emissions. Overall, the potential contribution of phytoplankton to the estimated OMP was low, despite the large algal biomass found in some of the lakes (Fig. 5). The main pathways of OMP therefore remain unclear, and the contribution of different pathways may vary among lake types, which may explain the diversity of OMP rates and potential drivers that have been reported in the literature. Our study extends the range of ecosystems where OMP has been detected, demonstrating that these shallow lakes fit previously hypothesized morphometric patterns of OMP contribution despite their high phytoplankton abundance, and establishes that phytoplankton does not appear to play a major direct role in shaping these ambient OMP rates.

Conceptual figure depicting the potential contribution of OMP (blue) to total lake CH4 diffusive flux (grey) and the potential contribution of phytoplankton CH4 production (green) to OMP ecosystem rates (orange), assuming the maximum potential scenario of contribution in all cases. The contribution of OMP (blue) to lake CH4 diffusive fluxes was obtained as mentioned in Section 7, the contribution of phytoplankton to OMP rates was obtained as explained in Section 11. Tree and bush symbols from Dylan Taillie and Jane Hawkey, respectively, and emergent macrophyte symbols from Tracey Saxby, Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Insights into OMP have shown that CH₄ sources in aquatic ecosystems are more variable and complex than previously recognized, thereby advancing our knowledge of CH4 cycling. Although these findings do not alter current estimates of total CH4 emissions, they refine our understanding of how these emissions are partitioned among different sources. Future research should focus on quantifying the contribution of OMP in other shallow and diverse ecosystems, as well as elucidating the mechanisms underlying phytoplankton-mediated CH₄ production, and the metabolic and environmental factors regulating this process.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Conrad, R. Microbial ecology of methanogens and methanotrophs. Adv. Agron. 96, 1–63 (2007).

Karl, D. M. et al. Aerobic production of methane in the sea. Nat. Geosci. 1, 473–478 (2008).

Damm, E. et al. Methane production in aerobic oligotrophic surface water in the central Arctic Ocean. Biogeosciences 7, 1099–1108 (2010).

Grossart, H. P., Frindte, K., Dziallas, C., Eckert, W. & Tang, K. W. Microbial methane production in oxygenated water column of an oligotrophic lake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 19657–19661 (2011).

Tang, K. W., McGinnis, D. F., Frindte, K., Brüchert, V. & Grossart, H. P. Paradox reconsidered: Methane oversaturation in well-oxygenated lake waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 275–284 (2014).

Bižić-Ionescu, M., Ionescu, D., Günthel, M., Tang, K. W. & Grossart, H.-P. Oxic methane cycling: New evidence for methane formation in oxic lake water. Biog. Hydrocarb. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78108-2_10 (2019).

Perez-Coronel, E. & Michael Beman, J. Multiple sources of aerobic methane production in aquatic ecosystems include bacterial photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 6454 (2022).

Tang, K. W., McGinnis, D. F., Ionescu, D. & Grossart, H. P. Methane production in oxic lake waters potentially increases aquatic methane flux to air. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 3, 227–233 (2016).

DelSontro, T., del Giorgio, P. A. & Prairie, Y. T. No longer a paradox: The interaction between physical transport and biological processes explains the spatial distribution of surface water methane within and across lakes. Ecosystems 21, 1073–1087 (2018).

Repeta, D. J. et al. Marine methane paradox explained by bacterial degradation of dissolved organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 9, 884–887 (2016).

Teikari, J. E. et al. Strains of the toxic and bloom-forming Nodularia spumigena (cyanobacteria) can degrade methylphosphonate and release methane. ISME J. 12, 1619–1630 (2018).

Yao, M., Henny, C. & Maresca, J. A. Freshwater bacteria release methane as a by-product of phosphorus acquisition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 6994–7003 (2016).

Wang, Q., Dore, J. E. & McDermott, T. R. Methylphosphonate metabolism by Pseudomonas sp. populations contributes to the methane oversaturation paradox in an oxic freshwater lake. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 2366–2378 (2017).

Peoples, L. M. et al. Oxic methane production from methylphosphonate in a large oligotrophic lake: Limitation by substrate and organic carbon supply. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 89, e01097-23 (2023).

Bižić-Ionescu, M., Ionescu, D., Günthel, M., Tang, K. W. & Grossart, H. Oxic methane cycling: New evidence for methane formation in oxic lake water. In Biogenesis of Hydrocarbons 1–22 (Springer, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53114-4_10-1.

Ernst, L. et al. Methane formation driven by reactive oxygen species across all living organisms. Nature 603, 482–487 (2022).

Bizic, M. Phytoplankton photosynthesis: An unexplored source of biogenic methane emission from oxic environments. J. Plankton Res. 43, 822–830 (2021).

Mao, Y. et al. Aerobic methane production by phytoplankton as an important methane source of aquatic ecosystems: Reconsidering the global methane budget. Sci. Total Environ. 907, 167864 (2024).

Batista, A. M. M., Woodhouse, J. N., Grossart, H. P. & Giani, A. Methanogenic archaea associated to Microcystis sp. in field samples and in culture. Hydrobiologia 831, 163–172 (2019).

Bogard, M. J. et al. Oxic water column methanogenesis as a major component of aquatic CH4 fluxes. Nat. Commun. 5, 5350 (2014).

Günthel, M. et al. Photosynthesis-driven methane production in oxic lake water as an important contributor to methane emission. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 2853–2865 (2020).

Hartmann, J. F. et al. High spatiotemporal dynamics of methane production and emission in oxic surface water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1451–1463 (2020).

Morana, C. et al. Methane paradox in tropical lakes? Sedimentary fluxes rather than pelagic production in oxic conditions sustain methanotrophy and emissions to the atmosphere. Biogeosciences 17, 5209–5221 (2020).

Bižić, M. et al. Aquatic and terrestrial cyanobacteria produce methane. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax5343 (2020).

Klintzsch, T. et al. Stable carbon isotope signature of methane released from phytoplankton. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103317 (2023).

Lenhart, K. et al. Evidence for methane production by marine algae (Emiliana huxleyi) and its implication for the methane paradox in oxic waters. Biogeosci. Discuss. 12, 20323–20360 (2015).

Klintzsch, T. et al. Methane production by three widespread marine phytoplankton species: Release rates, precursor compounds, and potential relevance for the environment. Biogeosciences 16, 4129–4144 (2019).

Klintzsch, T. et al. Effects of temperature and light on methane production of widespread marine phytoplankton. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 125, e2020GJ005793 (2020).

Donis, D. et al. Full-scale evaluation of methane production under oxic conditions in a mesotrophic lake. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–11 (2017).

Schroll, M., Liu, L., Einzmann, T., Keppler, F. & Grossart, H. P. Methane accumulation and its potential precursor compounds in the oxic surface water layer of two contrasting stratified lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 166205 (2023).

Günthel, M. et al. Contribution of oxic methane production to surface methane emission in lakes and its global importance. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Thottathil, S. D., Reis, P. C. J. & Prairie, Y. T. Magnitude and drivers of oxic methane production in small temperate lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11041–11050 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Strong Subseasonal variability of oxic methane production challenges methane budgeting in freshwater lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c07413 (2024).

Whiticar, M. J. Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. Chem. Geol. 161, 291–314 (1999).

Taenzer, L. et al. Low Δ12CH2D2 values in microbialgenic methane result from combinatorial isotope effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 285, 225–236 (2020).

Baliña, S., Sánchez, M. L., Izaguirre, I. & del Giorgio, P. A. Shallow lakes under alternative states differ in the dominant greenhouse gas emission pathways. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1–13 (2022).

Xiao, Q. et al. Spatial variations of methane emission in a large shallow eutrophic lake in subtropical climate. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 1597–1614 (2017).

Kosten, S. et al. Warmer climates boost cyanobacterial dominance in shallow lakes. Glob. Chang. Biol. 18, 118–126 (2012).

Izaguirre, I. et al. Which environmental factors trigger the dominance of phytoplankton species across a moisture gradient of shallow lakes?. Hydrobiologia 752, 47–64 (2015).

Iriondo, M., Brunetto, E. & Kröhling, D. Historical climatic extremes as indicators for typical scenarios of Holocene climatic periods in the Pampean plain. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 283, 107–119 (2009).

Geraldi, A. M., Piccolo Maria, C. & Perillo, G. E. Lagunas bonaerenses en el paisaje. Cienc. Hoy 21, 16–22 (2011).

Allende, L. et al. Phytoplankton and primary production in clear-vegetated, inorganic-turbid, and algal-turbid shallow lakes from the pampa plain (Argentina). Hydrobiologia 624, 45–60 (2009).

Baliña, S., Sánchez, M. L. & del Giorgio, P. A. Physical factors and microbubble formation explain differences in CH4 dynamics between shallow lakes under alternative states. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1–11 (2022).

Campeau, A. & Del Giorgio, P. A. Patterns in CH4 and CO2 concentrations across boreal rivers: Major drivers and implications for fluvial greenhouse emissions under climate change scenarios. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20, 1075–1088 (2014).

Soued, C. & Prairie, Y. T. The carbon footprint of a Malaysian tropical reservoir: measured versus modelled estimates highlight the underestimated key role of downstream processes. Biogeosciences 17, 515–527 (2020).

Koschorreck, M., Prairie, Y. T., Kim, J. & Marcé, R. Technical note: CO2 is not like CH4—limits of and corrections to the headspace method to analyse pCO2 in freshwater. Biogeosciences 18, 1619–1627 (2021).

DelSontro, T., Boutet, L., St-Pierre, A., del Giorgio, P. A. & Prairie, Y. T. Methane ebullition and diffusion from northern ponds and lakes regulated by the interaction between temperature and system productivity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, S62–S77 (2016).

Rasilo, T., Prairie, Y. T. & del Giorgio, P. A. Large-scale patterns in summer diffusive CH4 fluxes across boreal lakes, and contribution to diffusive C emissions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 1124–1139 (2015).

Reis, P. C. J., Thottathil, S. D., Ruiz-González, C. & Prairie, Y. T. Niche separation within aerobic methanotrophic bacteria across lakes and its link to methane oxidation rates. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 738–751 (2019).

Thottathil, S. D., Reis, P. C. J. & Prairie, Y. T. Methane oxidation kinetics in northern freshwater lakes. Biogeochemistry 143, 105–116 (2019).

Knox, M., Quay, P. D. & Wilbur, D. Kinetic isotopic fractionation during air-water gas transfer of O2, N2, CH4, and H2. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 20335–20343 (1992).

Rippka, R. & Herdman, H. Pasteur culture collection of cyanobacterial strains in axenic culture (Institut Pasteur, 1992).

Bischoff, H.W., Bold, H. C. Some soil algae from Enchanted Rock and related algal specie. In Phycological Studies IV vol. IV 1–95 (Univ. Texas Publ., Austin - Texas, USA, Texas, 1963).

Archibald, P. A. & Bold, H. C. Phycological studies (Univ. Texas Public, 1970).

Komárek, J. & Anagnostidis, K. Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa. Cyanoprokaryota 1. Chroococcales (Gustav Fischer, 1999).

Komárek, J. Cyanoprokaryota 2. Teil/2nd Part: Oscillatoriales. Susswasserflora von Mitteleuropa (2005).

Komárek, J. Chlorophyceae (Grunalgen) Ordnung Chlorococcales. (1983).

Izaguirre, I. et al. Comparison of morpho-functional phytoplankton classifications in human-impacted shallow lakes with different stable states. Hydrobiologia 698, 203–216 (2012).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Sanford, F. J. & Fox, W. Package ‘car’. Vienna R Found. Stat. Comput. 16(332), 333 (2012).

Murase, J. & Sugimoto, A. Inhibitory effect of light on methane oxidation in the pelagic water column of a mesotrophic lake (Lake Biwa, Japan). Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 1339–1343 (2005).

Shelley, F., Ings, N., Hildrew, A. G., Trimmer, M. & Grey, J. Bringing methanotrophy in rivers out of the shadows. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 2345–2359 (2017).

Thottathil, S. D., Reis, P. C. J., del Giorgio, P. A. & Prairie, Y. T. The extent and regulation of summer methane oxidation in northern lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 123, 3216–3230 (2018).

Oswald, K. et al. Light-dependent aerobic methane oxidation reduces methane emissions from seasonally stratified lakes. PLoS ONE 10, 1–22 (2015).

Broman, E. et al. No evidence of light inhibition on aerobic methanotrophs in coastal sediments using eDNA and eRNA. Environ. DNA 5, 766–781 (2023).

Sieczko, A. K. et al. Diel variability of methane emissions from lakes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 21488–21494 (2020).

Duan, X., Wang, X., Mu, Y. & Ouyang, Z. Seasonal and diurnal variations in methane emissions from Wuliangsu Lake in arid regions of China. Atmos. Environ. 39, 4479–4487 (2005).

Erkkilä, K. M. et al. Methane and carbon dioxide fluxes over a lake: Comparison between eddy covariance, floating chambers and boundary layer method. Biogeosciences 15, 429–445 (2018).

Podgrajsek E., Sahlée E., R. A. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 2292–2311 (2014).

Godwin, C. M., McNamara, P. J. & Markfort, C. D. Evening methane emission pulses from a boreal wetland correspond to convective mixing in hollows. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 118, 994–1005 (2013).

Martinez-Cruz, K. et al. Diel variation of CH4 and CO2 dynamics in two contrasting temperate lakes. Inl. Waters 10, 333–347 (2020).

Ordóñez, C. et al. Evaluation of the methane paradox in four adjacent pre-alpine lakes across a trophic gradient. Nat. Commun. 14, 2165 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Xie, H. Photomineralization and photomethanification of dissolved organic matter in Saguenay River surface water. Biogeosciences 12, 6823–6836 (2015).

Li, Y., Fichot, C. G., Geng, L., Scarratt, M. G. & Xie, H. The contribution of methane photoproduction to the oceanic methane paradox. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–10 (2020).

Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited. J. Geophys. Res. 12, 351–362 (1992).

Guérin, F. et al. Gas transfer velocities of CO2 and CH4 in a tropical reservoir and its river downstream. J. Mar. Syst. 66, 161–172 (2007).

Piovano, E. L. & Morales, J. A. Pampean Lakes. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-86028-7 (2025).

Algal Culturing Techniques. (Academic Press (Elsevier), Burlington, MA (USA), 2005).

Zhang, Y. & Xie, H. Photomineralization and photomethanification of dissolved organic matter in Saguenay River surface water. Biogeosciences 12, 6823–6836. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-6823-2015 (2015).

Young, J. N., Goldman, J. A., Kranz, S. A., Tortell, P. D. & Morel, F. M. M. Slow carboxylation of Rubisco constrains the rate of carbon fixation during Antarctic phytoplankton blooms. New Phytol. 205, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13021 (2015).

Jakobsen, H. H. & Markager, S. Carbon-to-chlorophyll ratio for phytoplankton in temperate coastal waters: Seasonal patterns and relationship to nutrients. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1853–1868. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10338 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Zolezzi for assistance in the field, A. Parkes for support with laboratory work and logistics and D. Kachanovsky for ambiental DNA analysis support. We are also grateful to C. Soued, P. Reis and Y. Prairie for their valuable discussions and insights. We are grateful to the International Society of Limnology (SIL) for awarding the Tonolli Prize to S. Baliña, which funded a significant share of the mesocosm field experiments. We thank the Ministry of Education of Argentina and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for funding the ALEARG fellowship, which enabled S. Baliña to conduct the phytoplankton strain experiments in Germany. We also thank the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina, for contributing to this study through a PhD fellowship awarded to S. Baliña. This work was also supported by the NSERC/HQ CarBBAS Industrial Research Chair, by Préstamo BID PICT RAICES 2017-2498 and by Préstamo BID PICT 2015-1509.

Funding

Préstamo BID PICT RAICES 2017–2498, Préstamo BID PICT 2015–1509, NSERC/HQ CarBBAS Industrial Research Chair, Society of Limnology (Tonolli prize) and Ministry of Education of Argentina alongside the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) (ALEARG fellowship).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. contributed substantially to the designing of the research, field work and data acquisition, phytoplankton strain isolation and phytoplankton experiments, molecular analysis, statistical analyses and writing of the manuscript. M.L.S. contributed substantially to the designing of the research, field work and data acquisition. M.B, D. I and H. P. G contributed substantially to the phytoplankton experiments carried out in Germany. S.T. contribute substantially to the isotopic mass balances. M. C. B contributed substantially to field work. A. J contributed substantially to the isolation of phytoplankton strains. P.A.G. contributed substantially to the designing of the research, analyses of the results and writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions