Abstract

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) has a high prevalence among the elderly, severely affecting their quality of life and imposing a considerable burden on social health insurance. Unicompartment knee arthroplasty (UKA) continues to be favored by clinicians as a minimally invasive procedure. Fixed-bearing prostheses require more precision than mobile-bearing prostheses, and fewer studies have been done on the biomechanics of their misalignment. To evaluate the biomechanical consequences of this misalignment under different conditions, gain insight into these effects, and offer clinical recommendations, a standard knee model and several femoral prosthesis deviation types were created and evaluated. The evaluation indicators include the focus on the upper surface of the polyethylene (PE) insert, the tibial cartilage surface, as well as the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL and LCL). Lateral translation of the femoral component center resulted in an 8.96% increase in maximum contact stresses (MCS) on the PE insert with a 5 mm deviation. Both varus and valgus alignments increased MCS on the PE insert, an increase of 11.34 and 12.46% for varus and valgus angles of 5°, respectively. For the tibial cartilage in the lateral compartment, MCS decreased with lateral movement of the femoral component center (standard position vs. 5 mm translation, 7.02 vs. 6.59 MPa) and increased with medial movement (standard position vs. 5 mm shift, 7.82 vs. 6.59 MPa). Stresses on the MCL increased with medial translation and valgus orientation of the femoral prosthesis, whereas stresses on the LCL increased with varus orientation and lateral translation of the femoral prosthesis. Surgeons should be vigilant about femoral prosthesis alignment, particularly when deviations exceed 5° or 5 mm, as such misalignments can lead to increased contact stresses and potential complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), the most prevalent progressive musculoskeletal condition, has garnered substantial research interest1. Single-compartment lesions are common, representing 50% of cases, with isolated medial tibiofemoral OA comprising 27%2. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) provides several benefits over total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for treating isolated medial tibiofemoral OA, with more bone preserving, earlier recovery, and more natural knee sensation3,4,5.

Despite significant advancements in UKA surgical techniques and implant designs over the past decades, the higher postoperative revision rate for UKA (18.2% at 15 years) compared to TKA (6.2% at 15 years) remains a significant obstacle to its broader adoption6, which includes aseptic loosening, polyethylene (PE) wear, and the development of arthritis in uninvolved compartments7,8. Previous studies have identified abnormal contact stress on the articular surface due to prosthesis malalignment as a primary cause of revisions9,10,11. The tolerance for faults in UKA prostheses is lower than TKA because more anatomical structures are preserved9. While the limited surgical exposure in UKA benefits the patient, it also poses a greater technical challenge for accurate component placement, making it more prone to errors12. Prosthesis misalignment can result in excessive stress on the PE insert or healthy compartments’ surfaces, accelerating wear and leading to inflammatory responses that ultimately cause prosthesis loosening and cartilage degeneration13,14. Therefore, in the context of UKA, the alignment and positioning of the components are deemed essential for optimal clinical outcomes and longevity. Extensive research has documented the biomechanical changes and clinical results related to the tibial component’s positioning10,11,15,16. However, investigations into the biomechanical consequences of femoral component malalignment in UKA remain limited9.

To our knowledge, biomechanical studies on fixed-bearing prostheses are still insufficient, despite their higher wear rates17 and the increased precision required in prosthesis positioning18 compared to mobile-bearing prostheses. Notably, the influence of femoral implant misalignment on stress distribution across major knee ligaments, such as the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL and LCL).

This research is designed to elucidate the biomechanical effects of femoral prosthesis misalignment as well as its impact on the main ligaments using finite element analysis (FEA). Various UKA models with differing femoral prosthesis rotations on the sagittal plane and translations on the coronal plane will be analyzed.

Materials and methods

Native knee model

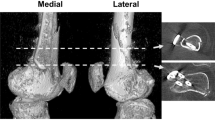

Imaging data were collected from a volunteer (23 years, 170 cm, and 60 kg), with no known musculoskeletal disorders. Informed consent for his participation and imaging procedures was gathered. Scanning of the left knee was conducted with a 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner and a 64-slice computed tomography (CT) scanner (Siemens, Germany). All human-involved procedures in this study were conducted in alignment with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research council, in addition to adhering to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical norms. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at our hospital (the First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College).

CT scans were conducted with a 0.6 mm thick slice, and MRI scans with a 1.0 mm thick slice, both in the sagittal plane, covering 15 cm of both the proximal tibia and distal femur. CT and MRI images obtained were then imported into Mimics software (version 20, Materialize, Leuven, Belgium) to generate 3D representations. These models were subsequently exported in stereolithography (STL) format and further processed using GeomagicWrap software (version 12.0, Geomagic, North Carolina, USA). The solid model was assembled and constructed in SolidWorks (version 2022, Dassault Systèmes S.A., USA) (Fig. 1).

UKA knee model

Upon creating the native knee model, an appropriately sized fixed-bearing UKA prosthesis (Link-Sled®, Germany) was selected. This prosthesis was scanned using the KSCAN-Magic 3D scanner (Aishankin Design Services Ltd., China). The refined and smoothed solid model of the prosthesis was imported into Abaqus 6.14 (Dassault Systèmes Simulia, Inc., France) for meshing, with detailed specifications provided in Table 1. All materials in this FE model were characterized by linear-elastic isotropic behavior, with mechanical properties defined based on previous studies9,19 (Table 2). Boolean operations were employed to simulate the medial UKA of the knee, ensuring that the PE implant’s height aligned with the native bone anatomy through a sagittal cut. The tibial implant was designed to cover the osteotomy surface optimally, avoiding inversion, eversion, and axial rotation.

In line with prior research9,20, a posterior slope of 5° was established via a transverse cut to align with the patient’s native tibial slope. The femoral implant was positioned perpendicular to the tibial prosthesis in the coronal plane, without axial rotation, covering the center of the medial femoral condyle and the distal end of the posterior femoral condyle as comprehensively as possible. A 1 mm thick layer of bone cement (methyl methacrylate) was simulated between the osteotomy surface and tibial implant to complete the fixed-bearing UKA model in its standard position, defined as a linearly elastic isotropic material (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Deviated prostheses were modeled with 3 mm and 5 mm of medial and lateral translation, as well as 3° and 5°of internal and external rotation, using the midline of the femoral prosthesis as a reference, as depicted in Fig. 2. The interface between cartilage and bone within the model was treated as fully bonded. All contact surfaces in the fixed-bearing UKA model utilized a finite sliding frictionless hard contact algorithm without penetration9,21. Convergence within the model was defined by a relative change of greater than 5% between two consecutive mesh refinements. The average element size for the simulated cartilage and menisci was 0.8 mm 21.

Stress loading and model validation

A compressive load of 1000 N along the mechanical axis of the femur downwards was applied to the different models to examine stress distributions, with a focus on the upper surface of the polyethylene (PE) insert, the tibial cartilage surface in the lateral compartment, and the MCL and LCL. The boundary conditions of each model were kept constant during loading, and convergence was verified after loading9,19.

The FE knee model underwent validation through axial load testing and simulation of the anterior drawer experiment. For validation under axial load, the femur was immobilized in the flexion-extension direction, whereas the lower surfaces of the tibia and fibula were entirely constrained22. This experiment setup aimed to mimic a realistic, functional scenario to validate the FEA model by preventing unwanted rotation and movement while allowing for the application and measurement of axial forces. Cartilage-to-bone and ligament-to-bone attachments were modeled as bindings, with the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus affixed to the tibial plateau. An axial load of 1150 N was applied along the mechanical axis23, and the resulting contact pressures were compared with data from previous research23. In the simulation of the anterior drawer experiment, tibiofibular flexion and femoral movement were restricted. An anterior load of 134 N, perpendicular to the coronal plane, was then applied at a reference point at the midpoint between the medial and lateral edges of the tibial plateau9,24. The observed tibial displacement was subsequently compared with findings from previous studies24.

Results

Validation of the UKA model

Under an axial load of 1150 N, the peak contact forces observed were 2.91 MPa for the medial meniscus and 1.49 MPa for the lateral meniscus. These values deviated by less than 3% from the contact pressures reported by Pena et al. 25. The maximum compressive stresses recorded in the medial and lateral menisci were 1.39 and 1.62 MPa, respectively, aligning closely with the values reported by Pena et al. (1.42 and 1.62 MPa)25. The simulated anterior drawer experiment revealed an anterior displacement of 4.92 mm at the tibial loading point, consistent with previous studies24.

Stress distribution on the PE insert

In the translation model, the stress on the PE insert’s upper surface was 38.19 MPa when the femoral prosthesis was positioned standardly. With lateral translations of 3 and 5 mm, the stress increased to 39.79 and 41.61 MPa, respectively. Conversely, medial translations resulted in decreased stress values, measuring 34.56 MPa for a 3 mm shift (a 9.51% reduction) and 32.94 MPa for a 5 mm shift (a 13.75% reduction).

Comparatively, the peak contact stresses on the medial compartment of PE insert exhibited notable increases at both varus and valgus angles of 5°, registering 42.52 and 42.95 MPa, representing increases of 11.34 and 12.46%, respectively. For varus and valgus angles of 3°, the maximum contact stresses (MCSs) were 39.74 and 38.40 MPa, which were 4.06 and 0.55% higher than the standard position. Details are illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4.

Stress distribution on the tibial cartilage of lateral compartment

In the translation model, the stress distribution on the tibial cartilage of the lateral compartment showed an opposite trend compared to the PE insert. Medial translations of 3 and 5 mm resulted in stress increases of 11.40 and 16.52%, respectively, with stress values of 7.82, 8.18, and 7.02 MPa for the standard position, 3 and 5 mm shifts. Conversely, lateral translations generally reduced stress on the cartilage surface, measuring 6.92, 6.59, and 7.02 MPa for 3, 5 mm translations, and the standard position, respectively.

In the varus/valgus model, the stress on the lateral compartment’s tibial cartilage decreased with valgus alignment, showing a reduction of 4.27% at 3° valgus and 8.26% at 5° valgus (with stress values of 6.72, 6.44, and 7.02 MPa for the standard position). This trend reversed with varus alignment, where a 3° varus increased stress by 2.28% and a 5° varus increased stress by 5.98% (with stress values of 7.18, 7.44, and 7.02 MPa for the standard position). Further details are provided in Fig. 4.

Stress distribution on MCL and LCL

In the translation model, the maximum principal stresses on MCL and LCL followed an opposite trend, generally decreasing and increasing with the lateral translation of the femoral implant. In the varus/valgus model, the maximum principal stresses on the MCL increased with the valgus alignment of the femoral prosthesis, rising by 11.34% at 3° and 11.94% at 5° (0.0335, 0.0373, and 0.0375 MPa for standard position, 3°, and 5°). Conversely, these stresses decreased with an increasing varus angle, showing reductions of 2.69% at 3° and 7.76% at 5°. Similarly, the maximum principal stresses in the LCL decreased by 5.00% at 3° valgus and 6.43% at 5° valgus (0.0140, 0.0133, and 0.0131 MPa for standard position, 3°, and 5°). These stresses increased with an increasing varus angle, with reductions of 0.71% at 3° and 5.00% at 5°. The detailed results are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Discussion

In treating single-compartmental knee osteoarthritis (KOA), UKA offers significant advantages over TKA, such as greater preservation of bone and cartilage tissues and improved postoperative knee function12. However, the limited wound exposure in UKA compared to TKA, particularly in obese patients, increases the risk of prosthesis misalignment, a primary factor in the need for revision surgery26,27. Reducing the revision rate of UKA prostheses remains a critical challenge, largely dependent on achieving proper alignment through accurate implant positioning and soft-tissue balancing12.

The appropriate fitting range for UKA prostheses, especially concerning the biomechanical impact of femoral implant positioning, remains uncertain. The biomechanical consequences of various placements of the femoral component within the knee joint are not yet fully comprehended. Jennings et al. 12 recommended positioning the femoral component centrally or slightly laterally on the medial femoral condyle to optimize tracking with the tibial component. Liu W and colleagues28 analyzed the effect of valgus/varus angles of the femoral components (Oxford mobile platform prosthesis) on mid-term outcomes post-UKA, revealing that an internal rotation angle between 0° and 6° could achieve superior mid-term results. Gulati et al. 29 conducted a follow-up study on 211 knees with medially implanted mobile-bearing UKAs using a minimally invasive technique over at least four years. They found that in 98% of cases, the femoral component was within 10° varus and 10° valgus, concluding that the Oxford UKA tolerates femoral malalignment of up to 10° due to its spherical femoral component. Unlike mobile-bearing prostheses, fixed-bearing prostheses cannot adjust for abnormal stress caused by misalignment, leading to increased edge loading and rapid wear, even with significant malalignment29. Consequently, fixed-bearing devices are more prone to deviation and less tolerant of fitting errors than mobile-bearing prostheses9. This study selected a fixed-bearing UKA prosthesis (Link-Sled®, Germany) to examine the mechanical effects of the femoral prosthesis on the internal structures of the knee joint.

Our findings align with previous studies9,21 that demonstrated the significant impact of the femoral component’s position on the contact stress experienced by the PE insert and the lateral compartment. In both varus and valgus fixed-bearing UKA models, there was an increase in contact stresses on the PE insert. However, an increase in contact stress within the lateral compartment was observed only in the varus model, supporting earlier findings30. This is attributed to the varying stiffness between the PE insert and the lateral compartment (elastic modulus: 685 MPa for the medial PE insert vs. 15 MPa for the lateral compartment)30. Additionally, a lateral deviation of 5 mm in the femoral prosthesis resulted in an 8.96% increase in contact stress on the PE insert, while the articular cartilage of the contralateral compartment exhibited a 6.13% reduction in contact stress relative to the standard positioning. Kang et al. 21 observed that lateral translations of 3 and 5 mm of the femoral component under gait loading conditions resulted in increases of 8.2 and 11.1% in MCS on the PE insert, respectively. These findings were further verified through static and dynamic modeling, demonstrating that femoral implant misalignment affects MCS on the PE insert and tibial cartilage of the lateral compartment.

This aligns with the earlier concept that the optimal implant position for UKA is to replace the original cartilage and replicate the natural joint line31. However, achieving a central femoral component placement in clinical settings is challenging due to factors like minimally invasive incisions and the absence of intraoperative proofreading instruments. Jaffry et al.32 compared the accuracy of UKA prosthesis positioning using patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) and robotic systems. Their results indicated that femoral implant positions and orientations were significantly more accurate with PSI, with mean errors of 2 mm and 4°, compared to 4 mm and 10° found in the conventional approach. Notably, no significant difference in accuracy was observed between the robotic and PSI methods.

A notable aspect of this research was the investigation of the effects of femoral prosthesis malalignment on stress distribution in MCL and LCL. The position of the femoral component was found to impact the maximum principal stresses on the MCL and LCL. Compared to the neutral position UKA FE model, the maximum principal stresses on the MCL increased in models with a valgus 5° or medial translation of 5 mm. Conversely, the stress distribution in the LCL increased less in the 5° valgus or 5 mm lateral translation models. This disparity may be due to the significant stiffness variability between the PE insert and lateral cartilage33. Thus, femoral prosthesis malalignment could alter stress in the MCL and LCL, potentially leading to stiffness or pain33.

This study does have some limitations. Firstly, while selecting a single volunteer for various deviation analyses eliminated heterogeneity, it also limited the representativeness of the results. KOA patients typically treated by UKA often have altered joint mechanics with different anatomical adaptations. The study will be expanded in the future to include an exploration of multiple prosthetic models representing different anatomical structures. Secondly, the study focused on static analysis and did not include gait cycle analysis under dynamic loading, which will be addressed in subsequent research. Thirdly, rotational activity of the knee was restricted under loading to simplify stress distribution testing. This aspect will be further evaluated in the future by in vitro mechanical testing. For instance, muscle tissue or dynamic stabilization effects will be incorporated into the model to assess the impact of malalignment more accurately on the PE and cartilage. Despite certain limitations, the insights garnered from this research provide valuable guidance for performing UKA.

Conclusions

The precise positioning of the femoral prosthesis in UKA, including varus, valgus angles, and translational shifts, significantly impacts the MCS on the PE insert and tibial cartilage, as well as the principal stresses in MCL and LCL. Surgeons must pay close attention to the alignment of the femoral prosthesis, particularly deviations exceeding 5°or 5 mm, as these misalignments can lead to increased contact stresses. To ensure the long-term survival of the prosthesis and enhance postoperative satisfaction, it is recommended that the femoral prosthesis be positioned centrally.

Finite element models of UKA with different translations and varus/valgus of the femoral prosthesis. a1: 5 mm medial translations; b1: 3 mm medial translations; c: standard position; d1: 3 mm lateral translations; e1: 5 mm lateral translations; a2: 5° varus; b2: 3° varus; d2: 3° valgus; e2: 5° valgus.

Structures | Units | Element node | Type of unit |

|---|---|---|---|

Bone | 62,268 | 78,886 | C3D10M |

Cartilage | 74,369 | 124,483 | C3D10M |

Ligaments | 52,739 | 85,725 | C3D10M |

Metal implants | 54,820 | 96,009 | C3D10M |

PE insert | 6834 | 8421 | C3D8R |

Meniscus | 68,621 | 106,012 | C3D10M |

Table 2. Material properties of different structures used in this study.

Structures | Elastic modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s ratio |

|---|---|---|

Cortical bone | 17,000 | 0.3 |

Cancellous bone | 350 | 0.25 |

Menisci | 27.5 | 0.33 |

Cartilage | 15 | 0.46 |

Cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloy | 210,000 | 0.29 |

Polyethylene (PE) | 850 | 0.4 |

Methacrylate | 1940 | 0.4 |

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy on ethical restrictions.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy on ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FEA:

-

Finite element analysis

- KOA:

-

Knee osteoarthritis

- LCL:

-

Lateral collateral ligament

- MCL:

-

Medial collateral ligament

- MCS:

-

Maximum contact stresses

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PE:

-

Polyethylene

- STL:

-

Stereolithography

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- UKA:

-

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

References

Primorac, D. et al. Knee osteoarthritis: A review of pathogenesis and State-Of-The-Art Non-Operative therapeutic considerations. Genes (Basel). 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11080854 (2020).

Stoddart, J. C., Dandridge, O., Garner, A., Cobb, J. & van Arkel, R. J. The compartmental distribution of knee osteoarthritis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 29, 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.011 (2021).

Wilson, H. A. et al. Patient relevant outcomes of unicompartmental versus total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 364, l352. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l352 (2019).

Wiik, A. V. et al. The unicompartmental knee is the preferred side in individuals with both a unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 3193–3199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05814-7 (2020).

Lombardi, A. V. Jr., Berend, K. R., Walter, C. A., Aziz-Jacobo, J. & Cheney, N. A. Is recovery faster for mobile-bearing unicompartmental than total knee arthroplasty? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 467, 1450–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0731-z (2009).

Di Martino, A. et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty has higher revisions than total knee arthroplasty at long term follow-up: a registry study on 6453 prostheses. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 29, 3323–3329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06184-1 (2021).

Saenz, C. L. et al. Early failure of a unicompartmental knee arthroplasty design with an all-polyethylene tibial component. Knee 17, 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2009.05.007 (2010).

Atik, O. S. & Sever, G. B. The survivorship of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is poorer compared with total knee arthroplasty. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 32, 274–275. https://doi.org/10.5606/ehc.2021.57899 (2021).

Ma, P. et al. Biomechanical effects of fixed-bearing femoral prostheses with different coronal positions in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03037-0 (2022).

Nie, Y., Yu, Q. & Shen, B. Impact of tibial component coronal alignment on knee joint biomechanics following Fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A finite element analysis. Orthop. Surg. 13, 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12927 (2021).

Sekiguchi, K. et al. Effect of tibial component alignment on knee kinematics and ligament tension in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint Res. 8, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1302/2046-3758.83.BJR-2018-0208.R2 (2019).

Jennings, J. M., Kleeman-Forsthuber, L. T. & Bolognesi, M. P. Medial unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 27, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00690 (2019).

Park, K. K., Koh, Y. G., Park, K. M., Park, J. H. & Kang, K. T. Biomechanical effect with respect to the sagittal positioning of the femoral component in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 30, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.3233/BME-191042 (2019).

Park, D. Y. et al. Polyethylene wear particles play a role in development of osteoarthritis via detrimental effects on cartilage, meniscus, and synovium. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 21, 2021–2029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2013.09.013 (2013).

Chatellard, R. et al. Medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: does tibial component position influence clinical outcomes and arthroplasty survival? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 99, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2013.03.004 (2013).

Wen, P. F. et al. Effects of lower limb alignment and tibial component inclination on the biomechanics of lateral compartment in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 130, 2563–2568. https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.217076 (2017).

van der List, J. P., Zuiderbaan, H. A. & Pearle, A. D. Why do medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasties fail today? J. Arthroplasty. 31, 1016–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.030 (2016).

Johal, S. et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: the Past, current Controversies, and future perspectives. J. Knee Surg. 31, 992–998. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1625961 (2018).

Tuncer, M., Cobb, J. P., Hansen, U. N. & Amis, A. A. Validation of multiple subject-specific finite element models of unicompartmental knee replacement. Med. Eng. Phys. 35, 1457–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.03.020 (2013).

Kwon, H. M., Kang, K. T., Kim, J. H. & Park, K. K. Medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to patients with a ligamentous deficiency can cause biomechanically poor outcomes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 2846–2853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05636-7 (2020).

Kang, K. T. et al. Effect of femoral component position on Biomechanical outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee 25, 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2018.03.003 (2018).

Dai, X. et al. How does the inclination of the tibial component matter? A three-dimensional finite element analysis of medial mobile-bearing unicompartmental arthroplasty. Knee 25, 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2018.02.004 (2018).

Peña, E., Calvo, B., Martinez, M. A., Palanca, D. & Doblaré, M. Why lateral meniscectomy is more dangerous than medial meniscectomy. A finite element study. J. Orthop. Res. 24, 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20037 (2006).

Ren, S. et al. Finite element analysis and experimental validation of the anterior cruciate ligament and implications for the injury mechanism. Bioeng. (Basel). 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9100590 (2022).

Pena, E., Calvo, B., Martinez, M. A., Palanca, D. & Doblare, M. Why lateral meniscectomy is more dangerous than medial meniscectomy. A finite element study. J. Orthop. Res. 24, 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20037 (2006).

Muller, P. E. et al. Influence of minimally invasive surgery on implant positioning and the functional outcome for medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 19, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2003.09.013 (2004).

McAuley, J. P., Engh, G. A. & Ammeen, D. J. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200111000-00036 (2001).

Liu, W. et al. The effect of femoral component valgus/varus angle on the mid-term efficacy of unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02648725.2023.2177436 (2023).

Gulati, A. et al. Influence of component alignment on outcome for unicompartmental knee replacement. Knee 16, 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2008.11.001 (2009).

Kang, K. T., Son, J., Baek, C., Kwon, O. R. & Koh, Y. G. Femoral component alignment in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leads to Biomechanical change in contact stress and collateral ligament force in knee joint. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 138, 563–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-2884-2 (2018).

Kwon, O. R. et al. Biomechanical comparison of fixed- and mobile-bearing for unicomparmental knee arthroplasty using finite element analysis. J. Orthop. Res. 32, 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22499 (2014).

Jaffry, Z. et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties: robot vs. patient specific instrumentation. Knee 21, 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2013.11.017 (2014).

Innocenti, B., Pianigiani, S., Ramundo, G. & Thienpont, E. Biomechanical effects of different varus and valgus alignments in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 31, 2685–2691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.006 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients for their cooperation and to all of the clinicians and support staff who were involved in caring for the patients enrolled in this study. This work was generously supported by the Major Project of Scientific Research Project of Provincial Education Department of Anhui Province (Grant number: 2022AH040170).

Funding

This work was generously supported by the Major Project of Scientific Research Project of Provincial Education Department of Anhui Province (Grant number: 2022AH040170).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F-X W and JZ were involved in data analysis, drafting, and reviewing of the manuscript. F-X W, JZ, and H-Z H were involved in data collection and analysis, as well as prepared tables and figures. QW, W-J H, and F-X W were the study designers and coordinators and helped with the critical appraisal of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

for his participation and imaging procedures was gathered. All human-involved procedures in this study were conducted in alignment with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research council, in addition to adhering to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical norms. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, F., Zhao, J., He, W. et al. Biomechanical analysis of femoral component malalignment in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep 15, 44071 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27623-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27623-4