Abstract

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are well-established etiological causes of invasive cervical cancer (ICC), with type 16 being the main contributor. This virus is often found to be integrated into the host genome in precancerous lesions and advanced cervical cancers. It is suggested that distinct lineages of HPV-16 differ in their persistence, carcinogenic potential, and geographic distribution. Given that genomic integration is one of the most critical steps in the development of cervical cancer, and lineage D has a higher propensity to integrate the viral genome into the host genome, it is necessary to conduct a study to investigate a possible relationship between HPV-16 lineages and physical status in Iran. In this study, a total of 125 laboratory-confirmed HPV-16-positive cervical samples (comprising 30 normal, 39 precancerous, and 56 cancerous specimens) were analyzed. The DNA level of E2 and E6 viral genes was measured using the quantitative Real-Time PCR method, and the E2/E6 ratio was used to calculate the physical status of the HPV-16 DNA in the studied samples. The full sequence of the E6 gene was also sequenced to determine HPV-16 lineages. Three lineages, A (32.8%), C (0.8%), and D (66.4%) of HPV-16, were found in this study. HPV-16 exhibits different integration profiles, with viral DNA detected in three forms: episomal, mixed, and integrated. The physical status of the genome was statistically different based on histology and age. The integrated form was more prevalent in ICC patients than in CIN I-III and normal groups (P=0.000048). Also, the integrated form of the genome was found in higher amounts in the age group >40 years in comparison to <40 years (P= 0.00117). Regarding lineages, no statistically significant differences were identified between HPV-16 lineages and the integration status. However, when the samples were stratified by histology status, an association between lineage D and integrated form was observed, while no association was found for lineage A. In conclusion, lineages A and D were found to be dominant in the Iranian population. Moreover, an association was found between lineage and integration status, as lineage D has a higher propensity to integrate than lineage A. However, it is recommended that further studies with larger sample sizes from different regions of Iran be conducted to estimate whether a specific lineage or sublineage has a higher chance of integrating into the host genome, persisting, and causing cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small and non-enveloped viruses genetically characterized by a circular double-stranded DNA that consists of early region genes (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7), late region genes (L1, L2), and an upstream regulatory region (URR)1,2. There are over 400 types of HPVs with almost 45 mucosal types that classified into two main categories including high-risk (HR) [including 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68] and low-risk (LR) [e.g., 6, 11, 42, 43, and 44]1,3. These viruses are linked to the development of cutaneous and mucosal lesions, ranging from benign lesions (e.g., anogenital warts [mostly caused by HPV-6 and 11]), to invasive tumors of both genitourinary tract—which include cervical, vulvar, vagina, penile, and anal carcinomas—as well as head and neck cancers. Among them, invasive cervical cancer (ICC) is believed to be the main well-established HPV-related cancer, affecting a significant proportion of non-immunized women, with an annual incidence of nearly 600,000 new cases and 340,000 deaths worldwide, and 1.90 per 100,000 women in Iran4,5,6. These viruses tend to infect the cervix transformation zone, leading to the development of premalignant cervical lesions classified as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grades I, II, and III, which, if left untreated, can progress to carcinoma4. HPV-16 is among the most frequently detected viral types in precancerous cervical lesions and ICC [~70%]7.

HPV-16 comprises four distinct lineages (A to D) and sixteen sub-lineages designated as A1-4, B1-4, C1-4, and D1-4, characterized if there were 1–10% and 0.5–1% differences in the nucleotide sequences, respectively8. The different biological activities of distinct HPV-16 lineages were shown in the world. Indeed, it was indicated that lineage D had an eight-fold increased risk of progression to cervical cancer in comparison to A1-3 variants9.

While most HPVs, including cancer-causing types, resolve within two years after initial detection—60% within one year and 90% within two years4—concerns remain regarding the virus’s potential to cause a persistent infection in a subset of infections by integrating the genetic material into the genome of the infected cells. This integration may occur as either a single copy or several concatemeric copies harboring full-length genomes, resulting in altered E6 and E7 expression levels by complete or partial E2 ORF disruption with a consequence of functional inactivation10. The timing and mechanism underlying HR-HPV DNA integration is yet to be well determined; however, the available information is controversial, with some data reporting the viral episomal forms exclusively in early stages of the disease, while others show integrated forms in cases of normal cytology, suggesting integration as an early carcinogenetic event11. Moreover, the current understanding of the integration status across different HPV-16 lineages in malignant lesions is limited, and its prognostic significance for the risk of tumor progression in precancerous lesions remains largely undetermined. However, some studies have shown that lineage D has a higher carcinogenic potential and a greater tendency to integrate the viral genome than the European variants, including A1-A39,12,13. According to previous studies in Iran, it has been indicated that lineage D of HPV-16 was more prevalent in ICC patients than in normal individuals14,15,16. Given that genomic integration is one of the most critical steps in the development of cervical cancer, and lineage D had a higher propensity to integrate the viral genome into the host genome, it is necessary to conduct a study to find a possible relationship between HPV-16 lineages and the physical status of the viral genome in Iran.

Materials and methods

Study population and sampling

This study involved a total of 129 fresh cervical tissue samples previously confirmed to be HPV16-positive. The inclusion criteria included samples that were diagnosed as HPV16 using L1 sequencing or COBAS assays, and the results of histopathology were determined.

Gynecological and histological examinations classified the cervical tissues according to the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) classification system into three groups: 30 cases (24%) with normal histology, 39 cases (31.2%) with CINI-III, and 56 cases (44.8%) with ICC, including 47 cases (83.9%) diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and 9 cases (16%) as adenocarcinoma (AdC). The median age was 40 years. Patients were referred to the women’s clinic at Imam Khomeini Hospital or Yas Hospital in Tehran, Iran, between 2022 and 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after a verbal explanation of the study’s aims and importance, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1402.126) following the Helsinki Declaration. Demographic data and histopathological diagnoses were collected from participants’ medical records.

DNA extraction and the investigation of lineages of HPV-16

HPV-16 DNA was isolated from tissue specimens by phenol–chloroform assay based on the previously performed procedure17 and stored at −20 °C until use. To identify lineages of HPV-16, the entire E6 region was amplified and sequenced according to a previously published procedure14. As E6 and E7 regions encode oncoproteins of HPV, and the length of the E6 gene was longer than the E7 gene, and the number of mutations was greater, the E6 gene was selected to investigate.

In brief, the nucleotide sequences of HPV 16 E6 (nucleotide 83-559) were investigated by PCR with the following primer pair: 5’-CCGAAACCGGTTAGTATAAAAGCA-3’ and 5’-CAGTTGTCTCTGGTTGCAAATCT 3’ to amplify a 571 bp amplicon. The PCR reactions and the thermal cycle conditions were done according to our previous study14. The PCR reaction was done in a 50 μl reaction mixture containing 100-200 ng of DNA template, 10 pmol of each primer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM of each dNTP, and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase. PCR amplification cycles included an initial 5-minute denaturation at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 40s, 55°C for 50s, and 72°C for 50s, and a final elongation at 72°C for 5 min. A reaction mixture lacking template DNA, as a negative control, was included in every set of PCR runs.

To investigate the HPV 16 E6 gene variations, all the PCR products were subjected to sequence using bidirectional sequencing with BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and a 3130 Genetic Analyzer Automated Sequencer as specified by Applied Biosystems manuals (Foster City, CA). Obtained sequences were edited by Bioedit software and converted to FASTA format. Then, our sequences were aligned with reference sequences (A1-4, B1-4, C1, C3, C4, and D1-4) that obtained from Home - Nucleotide - NCBI with the following accession numbers: K02718, AF536179, HQ644236, AF534061, AF536180, HQ644298, KU053915, KU053914, AF472509, KU053920, KU053925, HQ644257, AY686579, AF402678, and KU053931 to characterize the (sub)lineages in Bioedit software.

The physical status of the HPV-16 genome measurement

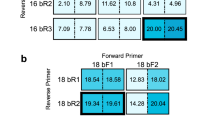

The DNA level of two viral genes—E2 and E6— were quantified by the method of absolute quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) using the specific primers (E2 [F: ACACAGACGACTATCCAGCG and R: CCGTCCTTTGTGTGAGCTGT] and E6 [F: AATGTTTCAGGACCCACAGG and R: GTTGCTTGCAGTACACACATTC]) to investigate the HPV integration status distinguishing the episomal, integrated, and mixed forms following the E2/E6 ratio calculation18. Each reaction consisted of 12.5 µL of SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™, 1 µL of each primer (10 pmol), and 1.5 µL of purified DNA in a total volume of 25 µL. In detail, the Real-Time PCR cycling conditions for HPV-16 E2 and E6 were as follows: initial denaturation (3 min at 95°C), followed by 45 cycles of denaturation (10 s at 95°C), annealing (40 s at 55°C), and extension at 60°C for 20 s. All samples were tested in duplicate, and a reaction mixture lacking a template as a negative control was used in each run. A melting curve analysis was performed to verify single gene-specific peaks by heating samples from 72°C to 98°C at the end of the amplification cycles. To ensure assay standardization, the recombinant plasmid pUC57 harboring the E2 and E6 genes of HPV-16 was employed as a quantitative reference for determining HPV E2 and E6 copy number. The assays were evaluated for linearity, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility to achieve optimal performance. A standard curve was generated using 10-fold serial dilutions of the recombinant plasmid ranging from 1.15×10⁶ to 1.15×101 copies, and the mean cycle threshold (Ct) values of replicate wells were plotted against the corresponding DNA copy numbers. The limit of detection (LoD) was defined as the lowest concentration at which the assay maintained linearity. Intra-assay variability was assessed using three independently prepared dilution series within a single experimental run, whereas inter-assay variability was determined using identical dilution series across three separate runs. The repeatability and reproducibility of the assays were expressed as the percentage of total variance. After quantification, the E2:E6 ratio was calculated. The ratios 0, 1, and <1 were considered for integrated, episomal, and mixed (a mixture of integrated and episomal forms) viral genomes, respectively18.

Statistical analysis

The Mantel−Haenszel χ2 or Fisher exact tests (two-sided) using Epi Info 7; Statistical Analysis System Software was used for data analysis. The P values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

One hundred twenty-five samples were successfully sequenced, while 4 samples failed to sequence. Our findings revealed that three lineages A, C, and D were found in our samples. The most common lineage was D (66.4%), followed by A (32.8%) and C (0.8%) lineages. All samples of the lineage D belonged to sublineage D1/4 (these two lineages cannot be distinguished as solely D1 or D4 based on the E6 sequence alone). Of the samples belonging to the A lineage, 21 samples (51.2%) were classified in sublineage A1 and 20 samples (48.8%) in sublineage A2. The only detected sample of the C lineage belonged to sublineage C1. Sequence analysis showed that 14 nucleotide substitutions occurred in the entire E6 gene (Table 1). Particular variants, including patterns 2, 3, 5, 8, and 9, were re-sequenced and confirmed that they were not the errors of sequencing. Of these 14 substitutions, 7 substitutions at positions G145T, A131G, A162G, G176A/C, C315G, C335T, T350G, resulted in amino acid changes at positions Q14H, R10G/I, Q20R, D25H/N, S71C, H78Y, L83V of the E6 protein, respectively. At least one amino acid change was observed in most samples (82.4%). Among these 7 amino acid changes, the most frequent change was L83V, which was observed in 103 samples (82.4%), followed by two changes, Q14H and H78Y, which were found in 84 samples (67.2%). The change R10G/I was observed in 4 samples (3.2%), and the three changes C71S, D25H/N, and Q20R were observed in one sample each.

To determine the genomic integration status of 125 studied HPV-16-positive cervical tissues, the expression levels of the E2 and E6 genes were analyzed, and the ratios were calculated. In total, 12 (9.6%), 79 (63.2%), and 34 (27.2%) samples were found to be positive for episomal (E2/E6 ratio=1), mixed (E2/E6 ratio <1), and integrated (E2/E6 ratio=0) HPV-16 DNA, respectively. The results of our investigation revealed that the E2/E6 ratio was significantly different in the tumor stages, with the most integration being detected in advanced cervical dysplasia (P=0.000048) (Table 2). In other words, the episomal form of DNA was observed in 33.3%, 7.7%, and 3.6% of normal, CIN I–III, and ICC cases, respectively, with frequency decreasing as histological severity increased. Conversely, the integrated form was detected in none of the normal group, 23.1% of the CIN I-III group, and 44.6% of the ICC group.

The results also reveal a statistically significant association between the age of patients and the viral genomic integration status (P=0.00117), with a notable increase in the integration rate among middle-aged and older patients. In our study, most cases harboring an integrated viral genome were diagnosed in women above 40 years (40.6%). Conversely, the episomal and mixed forms were more frequently detected in younger women (aged under 40 years). A comparison of the frequency of HPV-16 genomic integration based on the type of cervical cancer was made. The result showed that the frequency of absolute integration in AdC samples (55.6%) was found to be higher than in the SCC samples (42.5%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.259).

As shown in Table 2, no significant association was identified between HPV-16 lineages and the integration status (P=0.85). As indicated in Table 3, the HPV-16 lineages and the integration status were investigated with regard to histology status. In the A lineage group, the episomal form was detected in 18.2%, 7.2%, and 6.3% of normal, CIN I-III, and ICC cases, and no statistically significant differences were observed (P=0.116). However, in the D lineage group, the episomal form was detected at a lower frequency in ICC cases (2.5%) than 22.2% and 8% among normal and CIN I-III samples, respectively. This difference reached a statistically significant level (P=0.0028).

In the analysis of HPV-16 lineages and integration status, which was stratified by the type of ICC samples (SCC or AdC), the increased integrated form was found in lineage D than lineage A in the AdC group. However, this difference did not reach a statistically significant level (P=0.489). Also, among SCC patients, no statistically significant differences were found in this regard (P=0.845) (Fig. 1).

As shown in Table 4, the frequency of genomic integration status in terms of mutation at position 350 of the E6 gene of HPV-16 was also investigated. Although the integrated form was higher among samples with G mutation (30.1%) compared to the wild type nucleotide (T) (13.1%) at position 350 of the E6 gene, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.265).

Discussion

In this study, three lineages, A, C, and D, were identified in 32.8%, 0.8%, and 66.4% of samples, respectively. Our finding is in accordance with previous studies in Iran, which reported lineage D as the dominant lineage which followed by the A lineage15,16,19. It is suggested that the distribution of distinct HPV-16 lineages is population-dependent, and their geographical spreading can vary due to evolution related to the host population’s ethnicity20,21,22. In a global study, it was found that the A1 and A2 sublineages were most prevalent in Europe, South/Central America, North America, South Asia, and Oceania, while the A3 and A4 were most common in East Asia. Lineages B and C were found only in African samples. Lineage D was more prevalent in South/Central America and North Africa23.

The present study found three forms of HPV-16 DNA: episomal, mixed, and integrated in cervical samples. Although a large proportion of HPV-related cancers harbor integrated viral DNA, this is not always the case, as these cancers can also contain either extrachromosomal viral DNA (episomal) or a mix of episomal and integrated forms24. This implies that the dysregulation of E6 and E7 gene expression can be observed without DNA integration25.

Our findings showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the physical state of HPV-16 DNA across the various stages of cervical lesions, as the integrated viral DNA form was highly prevalent in CIN I-III and cancer lesions compared to controls. This finding is in line with previous studies, which show that a high copy of integrated HPV-16 DNA can be detected in high-grade cervical lesions and is associated with a poor disease prognosis26,27,28. Therefore, the examination of HPV-16 physical status is reported to be a promising test providing insight into CC risk29. However, in 76.7% of normal samples, a mixed form of HPV-16 genome integration was detected. It is worth mentioning that the rate of integration was lower than 30% in the normal group, while the rate of integration was more than 30% in the CIN I-III and malignant groups. Consistent with Kulmala’s study30, we identified HPV DNA in mixed form, the most commonly reported physical state in women with normal cervical histology. However, the integrated form was absent among the normal group in the present study. The mixed form of DNA may be a common phenomenon in HPV-16 infection, which could be observed not only in high-grade lesions and ICC but also in low-grade lesions and normal samples infected with the virus18,27,30, suggesting that HPV-16 integration may occur in the early stages of cervical neoplastic transformation27,30. In our study, the absolute episomal form was also detected in CIN I-III and malignant samples. This finding is in agreement with previous studies reporting the presence of episomal virus in cervical tumors4.

The age of patients is also regarded as a risk factor impacting the progression of cervical cancer. In contrast to the results reported by Karbalaie Niya et al.31, we found a statistically significant association between age and the frequency of viral genome integration. Compared to HPV-16-infected women with episomal status, those harboring the pure integrated viral DNA tend to be older, showing similarity with the cases in the literature32. Although the prevalence of the integrated form of HPV-16 DNA was higher in AdC than in SCC, no statistically significant differences were observed.

Considering genetic differences among HPV-16 lineages, there is a gap in our knowledge regarding whether such small-scale genetic variations influence the frequency of integration. To explore this, we assessed the integration status based on distinct HPV-16 lineages. In total, no integration differences were found between A and D lineages. However, when stratification concerning histology was done, our results indicated that a statistically significant difference was observed for D lineage, as this lineage had a greater tendency to integrate than the A lineage. A study using a three-dimensional organotypic model that supports the natural cycle of the virus showed that the Asian-American variant (lineage D) integrated into the host genome, but the European variant did not. The results of this study showed that lineage D has a greater predisposition to integrate into the host genome13.

Some studies extensively investigated the genetic variability of HPV-16 by examining the sequence of the E6 oncogene, aiming to discover nucleotide variations and amino acid substitutions impacting the oncogenicity of the virus and subsequently the initiation and progression of ICC33,34. The polymorphic mutation most frequently detected in non-European variants is the T350G mutation, which changes leucine to proline (L83V)35. In the present study, the frequency of genomic integration status in terms of mutation at position 350 of the E6 gene was evaluated, and the result indicated that variants with a G mutation had a higher integrated form than the wild-type nucleotide (T) at this position. However, no statistically significant differences were found, which may be due to the low sample size in this study.

The most important limitations of this study were the moderately sample size and the lack of differentiation D1 and D4 lineages solely based on the E6 sequence alone.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that two lineages, A and D of HPV-16, are common in the Iranian population. Also, our findings reaffirm the crucial role of integration as a key event in HPV-16 carcinogenesis, with integration showing a stronger association with ICC development, and confirm viral integration as a hallmark of ICC development. Regarding lineages, no statistically significant differences were identified between HPV-16 lineages and the integration status. However, when the samples were stratified by histology status, an association between lineage D and integrated form was observed, while no association was found for lineage A. It is recommended that further studies with larger sample sizes from different regions of Iran be conducted to estimate whether a specific lineage or sublineage has a higher chance of integrating into the host genome, persisting, and causing cancer.

Data availability

Sequence data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in GenBank and are available under accession numbers PP974705-PP974824 and MF066727-MF066813.

References

Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska, B. & Rudnicka, L. HPV infections—classification, pathogenesis, and potential new therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(14), 7616 (2024).

Lagström, S. et al. HPV16 and HPV18 type-specific APOBEC3 and integration profiles in different diagnostic categories of cervical samples. Tumour Virus Res. 12, 200221 (2021).

Burd, E. M. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16(1), 1–17 (2003).

Vallejo-Ruiz, V., Gutierrez-Xicotencatl, L., Medina-Contreras, O. & Lizano, M. Molecular aspects of cervical cancer: a pathogenesis update. Front. Oncol. 14, 1356581 (2024).

Anusha, T., Brahman, P. K., Sesharamsingh, B., Lakshmi, A. & Bhavani, K. S. Electrochemical detection of cervical cancer biomarkers. Clin. Chim. Acta 567, 120103 (2025).

Anjam Majoumerd, A. et al. Epidemiology of cervical cancer in Iran in 2016: A nationwide study of incidence and regional variation. Cancer Rep. 7(2), e1973 (2024).

van den Borst, E., Bell, M., Van Camp, G., Van Keer, S., Vorsters, A. Lineages and sublineages of high-risk human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer and precancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. –Bethesda. Md 1940 currens. (2025).

Burk, R. D., Harari, A. & Chen, Z. Human papillomavirus genome variants. Virology 445(1–2), 232–243 (2013).

Berumen, J. et al. Asian-American variants of human papillomavirus 16 and risk for cervical cancer: A case-control study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93(17), 1325–1330 (2001).

Myers, J. E. et al. Detecting episomal or integrated human papillomavirus 16 DNA using an exonuclease V-qPCR-based assay. Virology 537, 149–156 (2019).

Gudleviciene, Z., Kanopiene, D., Stumbryte, A. et al. Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 in cervical cancer cells. Open Med. 10(1) (2014).

Casas, L. et al. Asian-american variants of human papillomavirus type 16 have extensive mutations in the E2 gene and are highly amplified in cervical carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 83(4), 449–455 (1999).

Jackson, R. et al. Functional variants of human papillomavirus type 16 demonstrate host genome integration and transcriptional alterations corresponding to their unique cancer epidemiology. BMC Genom. 17(1), 851 (2016).

Khezeli, Z., Shoja, Z., Kaffashian, M., Soleimani-Jelodar, R. & Jalilvand, S. The lineage and sublineage investigation of human papillomavirus type 16 in Tehran, Iran, During 2022–2023: A Cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 8(5), e70680 (2025).

Vaezi, T. et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 lineage analysis based on E6 region in cervical samples of Iranian women Infection, genetics and evolution. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evolut. Genet. Infect. Dis. 55, 26–30 (2017).

Salehi-Vaziri, M. et al. Lineages and sublineages of human papillomavirus type 16 in cervical samples of Iranian women. Futur. Virol. 18(4), 215–224 (2023).

Jalilvand, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 variants in Kaposi’s sarcoma from Iranian patients. Virus Res. 163(2), 644–649 (2012).

Peitsaro, P., Johansson, B. & Syrjänen, S. Integrated human papillomavirus type 16 is frequently found in cervical cancer precursors as demonstrated by a novel quantitative real-time PCR technique. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40(3), 886–891 (2002).

Farhadi, A. et al. Type distribution of human papillomaviruses in ThinPrep cytology samples and HPV16/18 E6 gene variations in FFPE cervical cancer specimens in Fars province. Iran. Cancer Cell. Int. 23(1), 166 (2023).

Cornet, I. et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 variants in France and risk of viral persistence. Infect. Ag. Cancer. 8(1), 4 (2013).

Cornet, I. et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 genetic variants: Phylogeny and classification based on E6 and LCR. J. Virol. 86(12), 6855–6861 (2012).

Pimenoff, V. N., de Oliveira, C. M. & Bravo, I. G. Transmission between archaic and modern human ancestors during the evolution of the oncogenic human papillomavirus 16. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34(1), 4–19 (2017).

Clifford, G. M. et al. Human papillomavirus 16 sub-lineage dispersal and cervical cancer risk worldwide: Whole viral genome sequences from 7116 HPV16-positive women. Papillomavirus Res. 7, 67–74 (2019).

Kristiansen, E., Jenkins, A. & Holm, R. Coexistence of episomal and integrated HPV16 DNA in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. J. Clin. Pathol. 47(3), 253–256 (1994).

Darwich, L. et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution and human papillomavirus 16 and human papillomavirus 18 genomic integration in invasive and in situ cervical carcinoma in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 21(8), 1486–1490 (2011).

Zheng, Y., Peng, Z., Lou, J. & Wang, H. Human papillomavirus 16 physical status detection in preinvasive and invasive cervical carcinoma by multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction. Chin.-Ger. J. Clin. Oncol. 6, 72–79 (2007).

Huang, L.-W., Chao, S.-L. & Lee, B.-H. Integration of human papillomavirus type-16 and type-18 is a very early event in cervical carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Pathol. 61(5), 627–631 (2008).

Dutta, S. et al. Physical and methylation status of human papillomavirus 16 in asymptomatic cervical infections changes with malignant transformation. J. Clin. Pathol. 68(3), 206–211 (2015).

Gallo, G. et al. Study of viral integration of HPV-16 in young patients with LSIL. J. Clin. Pathol. 56(7), 532–536 (2003).

Kulmala, S. M. et al. Early integration of high copy HPV16 detectable in women with normal and low grade cervical cytology and histology. J. Clin. Pathol. 59(5), 513–517 (2006).

Karbalaie Niya, M. H. et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 integration analysis by real-time PCR assay in associated cancers. Transl. Oncol. 11(3), 593–598 (2018).

Kulmala, S. A. et al. Early integration of high copy HPV16 detectable in women with normal and low grade cervical cytology and histology. J. Clin. Pathol. 59(5), 513–517 (2006).

Bletsa, G. et al. Genetic variability of the HPV16 early genes and LCR. Present and future perspectives. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 23, e19 (2021).

Ortiz-Ortiz, J. et al. Association of human papillomavirus 16 E6 variants with cervical carcinoma and precursor lesions in women from Southern Mexico. Virol. j. 12(1), 29 (2015).

Huertas-Salgado, A. et al. E6 molecular variants of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16: an updated and unified criterion for clustering and nomenclature. Virology 410(1), 201–215 (2011).

Funding

This study has been funded and supported by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Grant no. 67712.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ and ZS have contributed to the design of the study; RS and ZK have done all tests, SV and AA have contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; SJ and HK have contributed to drafting the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects and the study was approved by the local ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1402.126).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karami, H., Soleimani-Jelodar, R., Khezeli, Z. et al. Exploring the association between the lineages of human papillomavirus type 16 and viral physical status in the development of cervical cancer in Iran. Sci Rep 15, 43922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27658-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27658-7