Abstract

Chronic resistance exercise training (RET) is largely understudied as a treatment intervention for anxiety disorders. Expectations may play a role in the effect of RET on anxiety and mood responses. Exploring placebo effects in chronic interventions is imperative to understanding the influence of expectations on psychological responses to chronic RET. This study quantified the associations between expectations of psychological outcomes of exercise (EPOE) and observed anxiety symptom and mood state responses to chronic RET among young adults with and without Analogue Generalized Anxiety Disorder (AGAD). An eight-week RET intervention was implemented among 54 young adults (25.8 ± 5y). 26 were randomized to the intervention group and 28 to waitlist (WL). Anxiety symptoms and mood state responses were measured pre and post RET and EPOE were measured at baseline. Spearman’s rho quantified associations between baseline expectations and anxiety and mood responses. There were no significant associations in the RET sample between EPOE and experienced psychological responses (all rho= -0.41 to -0.07, all p > 0.005). Preliminary findings suggest that the mental health benefits of chronic RET were independent of placebo effects, notwithstanding the potential limitations of small sample size and the non-mode-specific measure of expectations. Future research should explore the associations of mode-specific EPOE in larger sample sizes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their high prevalence anxiety disorders have significant costs, particularly relative to treatment and days lost from work1. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is the most common mental health disorder seen in primary care settings2. Like GAD, Analogue, or subclinical, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (AGAD) is characterized by persistent worry3, and operationalized by meeting evidence-based cut-scores on diagnostic screeners for GAD. Because subclinical and clinical GAD remain poorly treated, viable alternative and augmentation therapies need investigation.

Compared to placebo-conditions, frontline pharmacological and psychological interventions have shown efficacy for reducing anxiety4. However, less is known about the efficacy of exercise-based interventions. Available evidence shows that exercise-based interventions are healthful, potentially viable therapies for anxiety, supported by clinically meaningful improvements that may be generalisable to the wider population5. Previous interventions have largely focused on aerobic exercise training (AET), but the existing body of randomized controlled trial evidence supports the anxiolytic effects of resistance exercise training (RET)6. However, to further progress toward a precision medicine approach for personalized prescription of RET among individuals most likely to benefit, plausible psychobiological mechanisms that might underpin the anxiolytic benefits of RET warrant further investigation.

Available research into RET as an alternative treatment for anxiety disorders suggests the possible influence of placebo effects7. A placebo effect refers to any physiological or psychological response that can be attributed to the placebo or occurs solely as a consequence of expectations8.When scientific evidence is lacking and cannot be distinguished from placebo effects, treatments can be described as either complementary (used together with traditional medicine) or alternative (used instead of traditional medicine)9. Therefore, when improvements are experienced due to a complementary or alternative treatment, such as exercise, placebo effects cannot be disregarded. Despite this, exercise-based psychological interventions rarely assess the degree to which their observed effects may be attributable to placebo responses rather than the intervention mechanisms10 and thus, concerns remain around the consequences of placebo effects on psychological response to exercise11. Expectations have been suggested as an adequate construct to explore these effects because they are an established mechanism of placebo effects12. Expectations are a person’s beliefs that a given behaviour will result in a certain outcome13. Accounting for expectations allows for the further exploration of individual variability in the direction and magnitude of the psychological effects of exercise12. Both positive and negative expectations have the power to influence response; therefore, it is important to account for both the magnitude and the direction of expectations before exercise.

Recent meta-analytic evidence, which quantified the placebo effect of psychological responses to exercise training, found that up to 50% of responses were due to placebo effects14. Although expectancy manipulation research has yielded mixed results, some patterns have emerged, with elevating expectation found to be ineffective in manipulating psychological responses to seven-weeks of AET15. Conversely, modifying expectations by leading subjects to believe that their program was designed to specifically improve psychological well-being, enhanced psychological responses to 10-weeks of AET, suggesting a strong placebo effect16. More broadly, previous research focusing on positive verbal suggestions or manipulations of expectations has resulted in small to large effects on responses such as pain17,18. However, the majority of exercise-based interventions do not consider for placebo effects, which reduces methodological rigor and ability to confidently infer causality19. Moreover, the majority of research that has considered placebo effects has focused on acute placebo effects to aerobic exercise, resulting in a gap in the literature regarding exploration of placebo effects to chronic interventions, particularly RET20.

Accounting for placebo effects in the anxiolytic response to RET, particularly among those with elevated anxiety disorder symptoms, has implications for the conclusions about both the mechanisms that may underpin response to RET and the extent to which those factors may be manipulated to modify the response. For example, if placebo effects are demonstrated to influence response to RET, it presents the opportunity to potentially prime expectations to augment psychological responses. This is particularly important in chronic exercise training, as affective outcome expectancy has been found to be a strong predictor of exercise adherence six-months post-interventions21. Recently, we found no evidence of expectation-related placebo effects on mood responses to acute resistance exercise22. However, the observed effect of exercise on mood responses was modest, therefore limiting the opportunity for studying the contribution of placebo effects. Therefore, it is important to examine the potential placebo effects in chronic RET interventions where psychological improvements are present, to draw stronger conclusions about plausible placebo mechanisms.

Thus, through secondary analysis of existing RCT data, the associations between baseline psychological expectations of response to exercise training and anxiety and mood responses to eight-weeks of RET were quantified to examine the extent to which placebo effects influence psychological responses to chronic RET. The authors hypothesized that baseline expectations of psychological responses to exercise training would be positively associated with the observed anxiety and mood responses to an eight-week chronic RET intervention.

Methods

This trial complied with the consolidated standards of reporting trials checklist (CONSORT)23. This research protocol was approved by the University of Limericks Research Ethics Committee (EHSREC No: 2017_03_18_EHS) and was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Trial design

This manuscript reports secondary analysis findings from a previously published two armed-parallel RCT (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04116944; registration date: 018-01−18)24,25.

Participants

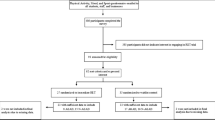

Participants were recruited through flyers, word of mouth and emails to complete an online battery of mood and physical activity questionnaires. Eligibility followed the following criteria: (i) aged between 18 and 40 years old (ii) No contradicting medical issues or injuries (iii) not currently pregnant or post-partum. For the secondary analyses reported here, data from 54 young (25.7 ± 5y) untrained adults were used. Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the included participants.

RET intervention

An eight-week chronic RET RCT was used to examine the influence of expectations of psychological responses to exercise on observed RET-induced anxiety symptom and mood state responses. Participants in the RET intervention completed a 3-week familiarization process prior to the 8-week RET. Consistent with WHO and ACSM guidelines26,27, RET sessions were fully supervised, completed twice weekly and designed to be 45 min in duration. Each session included eight exercises, with two sets of 8–12 repetitions. Exercises included: barbell back squat, barbell bench, barbell bent-over rows, hexagon bar deadlift, dumbbell lateral raises, dumbbell bicep curls, dumbbell lunges and abdominal crunches. Intensity of the sessions were increased or decreased by 5% 1RM weekly based on reps in reserve. Standardised instructions were used by investigators to measures participant’s perceived exertion using the self-reported Borg’s 6–20 scale (RPE)28 and a 10-point Muscle Pain Intensity Scale to measure muscle soreness (MS)29 after each exercise. Self-reported questionnaires were completed pre and post the 8-week intervention. Expectations of psychological outcomes to exercise were measured at baseline.

Control condition

Participants randomized to the waitlist group were placed on an eight-week waiting list. Self-reported mood questionnaires were completed pre and post the eight-week intervention. Expectations of psychological outcomes to exercise were measured at baseline.

Primary outcomes

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the 20-item trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y2)30. This inventory demonstrated strong internal consistency α = 0.94 (ICC = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.89 to 0.95). Changes in anxiety symptoms were quantified using the delta (i.e., change score) of self-reported STAI-Y2 scores, calculated as post-intervention score minus pre-intervention score.

Expectations regarding psychological responses to exercise

Expectations were measured using the 14-item Expected Psychological Outcomes of Exercise Questionnaire (EPOE) at baseline. Lindheimer et al.12 developed a survey which records both the direction and magnitude of psychological responses to exercise, which allows for the extent to which these expectations are positive or negative to be determined by the participant. Expectations of anxiety, depression, ability to relax and psychological well-being were recorded.

Mood States

Mood state responses were assessed using the five-item subscales of the Profile of Mood States – Brief Form (POMS-B)31. Feelings of tension, depressed mood and total mood-disturbance were quantified. Changes in mood state response were quantified using the delta (i.e., change score) of self-reported POMS-B scores, calculated as post-intervention score minus pre-intervention score. Negative change scores indicated negative responses, and positive change scores indicated positive responses.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS 28.0. Descriptive statistics examined baseline differences in age, anxiety symptoms, and mood state scores (See Table 1). Associations between baseline expectations and anxiety symptoms and mood state responses (change scores) to RET were quantified using Spearman’s rank (Rho) correlations (See Table 2). Each psychological construct was matched with an expectation measure that assessed the same underlying construct. Anxiety symptoms were matched with expectations of anxious mood; feelings of depressed mood were matched with expectations of depressed mood; feelings of tension were matched with expectations of ability to relax, and feelings of total mood disturbance were matched with expectations of psychological well-being. Potential baseline differences in expectations between RET and WL were quantified using Mann-Whitney U tests (See Table 3). Within-group differences for anxiety symptoms and mood state responses were quantified using paired sample t-tests and Hedges’ g; effect sizes were computed such that positive effect sizes indicated improved outcomes (See Table 4). To control for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied. The significance level (α) was set at p < 0.005 to avoid an inflated risk of a type 1 error and reduce the likelihood of false-positive findings. This adjusted threshold was derived by dividing the p-value (0.05) by the number of planned statistical tests, which ensured that each test was evaluated at a lower threshold for significance.

Results

Total sample

Resistance exercise training

RET significantly improved anxiety symptoms (g = 1.25, p < 0.001) and mood states (Depressed mood: g = 0.62, p < 0.003; Total mood disturbance: g = 0.62, p < 0.003) and non-significantly improved Tension: g = 0.42, p < 0.03, with all effects ranging from small-to-moderate to large magnitude (See Table 4).

Waitlist

No significant differences were found for waitlist (anxiety symptoms: g = 0.45, p ≥ 0.22; Tension: g = 0.22, p ≥ 0.24; Depressed mood: g = 0.09, p ≥ 0.62; Total mood disturbance: g = 0.23, p ≥ 0.23) (See Table 4).

Resistance exercise training and expectations

There were no significant differences in baseline exercise expectations between RET and waitlist (See Table 3, all p ≥ 0.12). After adjusting for multiple testing, there were no significant associations between expectations and observed anxiety symptom or mood state responses to RET (anxiety symptoms: rho= -0.30, p ≥ 0.13); Tension: rho= -0.07), p ≥ 0.71; Depressed mood: rho= −0.41, p ≥ 0.04; Total mood disturbance: rho= −0.07, p ≥ 0.72) (See Table 2).

Waitlist and expectations

There were no significant associations between expectations and observed anxiety and mood state responses to waitlist (anxiety symptoms: rho=−33, p ≥ 0.11; Tension: rho = 0.37, p ≥ 0.05; Depressed mood; rho= −0.11, p ≥ 0.58 and Total mood disturbance; rho = 0.16, p ≥ 0.39) (See Table 2).

Discussion

These secondary analyses quantified the associations of baseline expectations of psychological outcomes to exercise and actual observed anxiety symptom and mood state responses to eight-weeks of guidelines-based chronic RET among young adults with and without AGAD. Baseline expectations were not associated with observed anxiety symptom or mood state responses to chronic RET or waitlist control. However, there was a small magnitude association between expectations of depressed mood and feelings of depression in the chronic RET sample that did not survive adjustment for multiple testing. These findings are novel, as [to the authors’ knowledge] this is the first attempt to account for baseline expectations of psychological outcomes to exercise on observed anxiety and mood responses to chronic RET in this population. The lack of observed associations suggests that anxiety and mood responses to chronic RET do not appear to be significantly influenced by placebo effects and/or this instrument is not equipped to detect these changes.

Present findings indicated eight-weeks of RET elicited a large magnitude, potentially clinically-meaningful improvement in anxiety symptoms (g = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.73 to 1.75, p < 0.001), which, as expected, was not observed in the waitlist control group (g = 0.45, 95%CI: 0.06 to 0.84, p ≥ 0.22). These findings reiterate the growing body of evidence supporting the anxiolytic effects of chronic RET, particularly among young adults with elevated symptoms, and align with meta-analytic evidence showing that RET significantly reduced anxiety symptoms compared to waitlist controls to a small magnitude (Hedges’ d = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.17 to 0.44, p < 0.001)6. Despite the observed psychological improvements, there was no significant association between expectations of anxious mood and observed anxiety responses (rho= −0.30, p > 0.13), suggesting that the anxiolytic responses observed are likely attributable to other mechanisms outside of placebo effects. Similarly, RET significantly reduced feelings of depressed mood (g = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.21 to 1.03, p < 0.003) and total mood disturbance (g = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.21 to 1.03, p < 0.003) to a moderate, potentially clinically-meaningful magnitude, but there were no significant associations between expectations and psychological responses (all p > 0.005). These findings are consistent with recent reports on acute resistance exercise, which found no associations between expectations and psychological responses (all rho= −0.05 to 0.16). However, unlike this prior work22, psychological benefits were observed following chronic RET. The current findings extend previous work by showing that chronic RET significantly improved anxiety and mood states, allowing for a more meaningful exploration of the extent to which expectations might have influenced these meaningful changes. These novel findings strengthen the placebo literature by providing initial evidence that the psychological benefits of RET appear to be largely independent of placebo responses, even in cases where positive psychological responses are clear. However, it is important to note that expectations were assessed at baseline and did not account for any potential changes in expectations across the course of the 8-week program.

Interestingly, there was a small magnitude association between expectations of depressed mood and the moderate, potentially clinically-meaningful RET-induced improvement in feelings of depressed mood; however, this association did not survive adjustment for multiple testing (p > 0.005). Though herein the association was not significant following rigorous adjustment for multiple testing, the moderate magnitude association warrants further investigation in future research, particularly given both the high comorbidity of elevated depressive symptoms among those with GAD and the efficacy of RET to improve elevated depressive symptoms and major depression32.

The present findings somewhat diverge from previous meta-analytic evidence for aerobic exercise training which attributes up to 50% of psychological responses to exercise to placebo effects14, likely due to the small sample size and subclinical population which plausibly may have impacted results. However, the mixed findings in the placebo literature highlight the complexity of expectancy effects on psychological responses to exercise training. Notably, Arbinaga et al.15 reported no added benefits to elevating participants expectations on psychological responses to seven-weeks of aerobic exercise training, whereas Desharnais et al.16 demonstrated modifying expectations by informing subjects that taking part in this training programme would improve their psychological well-being yielded significant psychological improvements compared to control. Moreover, Vaegter et al.18 reported that both positive and negative pre-exercise information influenced pain pressure tolerance (PPT) following exercise, pre-exercise positive information increased participants PPT following exercise and pre-exercise negative information decreased participants PPT following exercise. It is plausible that these findings can be extended to exercise-induced mood responses, particularly given overlapping neurobiology of pain and mood responses to exercise. The inconsistencies across previous studies also suggests that the association of expectations on psychological responses are potentially influenced by factors such as the type and frequency of expectancy information and/or manipulation.

Though RET positively improved anxiety and mood responses, negative expectations have the potential to reduce the benefits of a given treatment, and better understanding individuals’ expectations may be helpful to healthcare practitioners to reassure patients regarding treatment viability, efficacy, and the importance of compliance33. There is limited research regarding both specific expectations and psychological responses to exercise in individuals with anxiety disorders (e.g., GAD)11. Current recommendations from the exercise placebo literature suggest measuring expectations at different time points throughout the intervention to account for variability, bias response, and study specific effects34. Additionally, there is insufficient research into a valid exercise placebo that accurately reflects all the elements of the treatment without the active agents (mechanisms), and what these exact mechanisms are14.

Findings should be interpreted in the context of potential limitations. Firstly, the lack of mode-specific psychological measurements of expectations regarding RET potentially impacted individuals’ responses, mode-specific measurements are important because participant’s general expectations about exercise training may differ from their expectations of RET specifically. Secondly, there was no mid-point or post-trial measurement of expectations which is necessary to better account for confounders. Third, there are several other established mechanisms of placebo effects (e.g., conditioning, social observation) that were not measured here. Thus, we cannot fully rule of the possibility that placebo effects were indeed present in the observed effect of exercise. Finally, the small sample size limited the detection of stable associations between expectations and psychological responses, and therefore results should be interpreted with caution. Future research should strive for adequately powered trials with large sample sizes to increase confidence in the stability of associations between expectations and psychological responses.

Anxiety and mood responses to chronic RET have the potential to be influenced by expectations of psychological response, but expectations were not associated with actual RET-induced anxiety and mood state responses herein. However, continued investigation of expectations is critical to advance the understanding of the true mechanisms of RET effects on anxiety and mood. Future research developing trials that measure study specific expectations for resistance exercise at different time points using an active exercise placebo are needed to further elucidate which plausible mechanisms of the treatment are most strongly associated with actual response. These advances will further expand on the limited evidence surrounding the true mechanisms of chronic RET on anxiety and mood responses. Given the lack of research and the demonstrated viability of RET to reduce anxiety, trials exploring the association of specific expectations of chronic RET on actual anxiety and mood responses to chronic RET are warranted.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Olthuis, J. V., Watt, M. C., Bailey, K., Hayden, J. A. & Stewart, S. H. Therapist-supported internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (ed. The Cochrane Collaboration) CD011565 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011565.

Hoge, E. A., Ivkovic, A. & Fricchione, G. L. Generalized anxiety disorder: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ 345, e7500–e7500 (2012).

Portman, M. E., Riskind, J. H. & Rector, N. A. Generalized anxiety disorder. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior 215–220 (Elsevier, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00175-0. (2012).

Chen, T. R., Huang, H. C., Hsu, J. H., Ouyang, W. C. & Lin, K. C. Pharmacological and psychological interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: A network meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr Res. 118, 73–83 (2019).

Herring, M. P., Gordon, B. R., McDowell, C. P., Quinn, L. M. & Lyons, M. Physical activity and analogue anxiety disorder symptoms and status: mediating influence of social physique anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 282, 511–516 (2021).

Gordon, B. R., McDowell, C. P., Lyons, M. & Herring, M. P. The effects of resistance exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 47, 2521–2532 (2017).

Beedie, C. et al. Consensus statement on placebo effects in sports and exercise: the need for conceptual clarity, methodological rigour, and the Elucidation of Neurobiological mechanisms. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 18, 1383–1389 (2018).

Benedetti, F. et al. Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses. J. Neurosci. 23, 4315–4323 (2003).

National Health Service. The Placebo Effect and Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (2016). https://familyserviceshub.havering.gov.uk/kb5/havering/directory/advice.page?id=LYM-rzuuyo0

Szabo, A. Acute psychological benefits of exercise: reconsideration of the placebo effect. J. Ment Health. 22, 449–455 (2013).

Herring, M. P., Gordon, B. R., Murphy, J., Lyons, M. & Lindheimer, J. B. The interplay between expected psychological responses to exercise and physical activity in analogue generalized anxiety disorder: a cross-sectional study. IntJ Behav. Med. 30, 221–233 (2023).

Lindheimer, J. B., Szabo, A., Raglin, J. S. & Beedie, C. Advancing the Understanding of placebo effects in psychological outcomes of exercise: lessons learned and future directions. EJSS 20, 326–337 (2020).

Bandura, A. & Self-Efficacy The Exercise of Control. In (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Lindheimer, J. B., O’Connor, P. J. & Dishman, R. K. Quantifying the placebo effect in psychological outcomes of exercise training: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 45, 693–711 (2015).

Arbinaga, F., Fernández-Ozcorta, E., Sáenz‐López, P. & Carmona, J. The psychological effects of physical exercise: A controlled study of the placebo effect. Scand. J. Psychol. 59, 644–652 (2018).

Desharnais, R., Jobin, J., Côté, C., Lévesque, L. & Godin, G. Aerobic exercise and the placebo effect: a controlled study. Psychosom. Med. 55, 149–154 (1993).

Peerdeman, K. J. et al. Relieving patients’ pain with expectation interventions: a meta-analysis. Pain 157, 1179–1191 (2016).

Vaegter, H. B., Thinggaard, P., Madsen, C. H., Hasenbring, M. & Thorlund, J. B. Power of words: influence of preexercise information on hypoalgesia after exercise—randomized controlled trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 52, 2373–2379 (2020).

Boot, W. R., Simons, D. J., Stothart, C. & Stutts, C. The pervasive problem with placebos in psychology: why active control groups are not sufficient to rule out placebo effects. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 445–454 (2013).

Beedie, C. J. & Foad, A. J. The placebo effect in sports performance: a brief review. Sports Med. 39, 313–329 (2009).

Gellert, P., Ziegelmann, J. P. & Schwarzer, R. Affective and health-related outcome expectancies for physical activity in older adults. Psychol. Health. 27, 816–828 (2012).

Rice, J. M., Gordon, B. R., Lindheimer, J. B., Lyons, M. & Herring, M. P. Associations between expected and observed psychological responses to acute resistance exercise in analogue generalized anxiety disorder. Sci. Rep. 15, 11378 (2025).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G. & Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. (2010).

Gordon, B. R., McDowell, C. P., Lyons, M. & Herring, M. P. Acute and chronic effects of resistance exercise training among young adults with and without analogue generalized anxiety disorder: A protocol for pilot randomized controlled trials. MENPA 18, 100321 (2020).

NIH. The Resistance Exercise Training for Worry Trial. ClinicalTrails.gov. (2018). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04116944?term=nct04116944&rank=1(Accessed: 25/08/2025).

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 25-27. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979 (WHO, 2010).

American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. MSSE 41, 687–708 (2009).

Borg, G. & Ottoson, D. Perception of Exertion in Physical Exercise. London. (1986).

Cook, D. et al. Naturally occurring muscle pain during exercise: assessment and experimental evidence. MSSE 57, 999–1012 (1997).

Spielberger, C. D. & Gorsuch, R. L. Manual for the state_trait anxiety inventory (form Y): self-evaluation questionnaire. (1983).

Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M. Profile of Mood States (POMS). in STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales (eds. Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M.) 285–286 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2011). doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9893-4_68.

Gordon, B. R. et al. Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms: meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 75, 566 (2018).

Colloca, L. The placebo effect in pain therapies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 59, 191–211 (2019).

Lindheimer, J. B., O’Connor, P. J., McCully, K. K. & Dishman, R. K. The effect of light-intensity cycling on mood and working memory in response to a randomized, placebo-controlled design. Psychosom. Med. 79, 243–253 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jennifer M. Rice: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization. Brett R. Gordon: Conceptualization, Data Collection, Validation, Writing – Review and Editing. Jacob B. Lindheimer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review and Editing. Mark Lyons: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision. Matthew P. Herring: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This research protocol was approved by the University’s Research Ethics Committee (EHSREC No: 2017_03_18_EHS), and all included participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the trial.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rice, J.M., Gordon, B.R., Lindheimer, J.B. et al. Associations between expectations and responses to chronic resistance exercise in young adults with and without analogue generalized anxiety disorder. Sci Rep 15, 43991 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27663-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27663-w