Abstract

Cortical arousals are brief brain activations that disrupt sleep continuity and contribute to cardiovascular, cognitive, and behavioral impairments. Although polysomnography is the gold standard for arousal detection, its cost and complexity limit use in long-term or home-based monitoring. This study presents a noninvasive, machine learning–based framework for detecting cortical arousals using the RestEaze™ system, a leg-worn wearable that records multimodal physiological signals including accelerometry, gyroscope, photoplethysmography (PPG), and temperature. Across multiple methods tested, including logistic regression, XGBoost, and Random Forest classifiers, we found that features related to movement intensity were the most effective in identifying cortical arousals, while heart rate variability had a comparatively lower impact. The framework was evaluated in 14 children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) undergoing assessment for restless leg syndrome–related sleep disruption. The Random Forest model achieved the best overall performance, with a ROC-AUC of 0.94 and an AUPRC of 0.55, substantially higher than the baseline prevalence of arousals (~ 0.07). For the arousal class specifically, it reached a precision of 0.57, recall of 0.78, and F1-score of 0.65. These findings support the feasibility of wearable-based machine learning for real-world arousal detection, demonstrated here in a pediatric ADHD cohort with sleep-related behavioral concerns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cortical arousals are brief interruptions in electroencephalographic (EEG) activity that fragment sleep without full awakening. Although transient, these arousals contribute to autonomic activation and disrupted sleep pattern, with growing evidence linking them to hypertension, cognitive decline, and elevated cardiovascular risk1,2,3. Total sleep duration less than 5 h per night is considered high-risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality4. Disrupted or insufficient sleep has also been associated with systemic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and increased all-cause mortality5. Elevated rates of sleep disturbances, including cortical and autonomic arousals, have also been observed in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)6,7,8. Early and accurate detection of these arousals may offer clinical insights into the relationship between poor sleep quality and daytime behavioral symptoms that may reveal patterns that differ by clinical subtype.

Polysomnography remains the gold standard for detecting cortical arousals9,10, yet its high cost, complexity, and requirement for overnight clinical supervision limit its use for large-scale or long-term monitoring11. Consumer sleep technologies, such as sleep trackers, offer a non-invasive, scalable approach to sleep monitoring, with the potential to support early identification of sleep fragmentation in home environments. While these devices offer greater accessibility, they often suffer from poor agreement with polysomnography, particularly in detecting brief or motionless arousals12. A multicenter validation study involving 11 wearable, nearable, and airable consumer sleep trackers confirmed substantial variation in performance across devices, with some showing macro F1-scores as low as 0.26 when compared to Polysomnography13. However, the growing integration of wearable sleep technologies into daily life offers a valuable opportunity to develop advanced frameworks that can effectively use these technologies to detect clinically relevant features of sleep.

One promising solution involves tracking leg movements during sleep, which frequently occur alongside cortical arousals, especially in populations with conditions like restless leg syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, or ADHD14,15,16,17. Recent studies using wearable leg sensors have shown that leg movements during sleep features can effectively distinguish arousals, and that leg-EEG signal coupling may reflect deeper physiological mechanisms of sleep disruption18,19. In this study, we evaluate multimodal sensor data from a leg-worn wearable, RestEaze™, to detect cortical arousals using interpretable machine learning models, with the aim of advancing practical and reliable sleep health monitoring solutions outside of traditional clinical settings.

The RestEaze™ system integrates accelerometry, gyroscope, photoplethysmography (PPG), and temperature sensors, offering a comprehensive view of movement and physiological dynamics during sleep. In a prior pilot study using a similar platform, we introduced neuro-extremity analysis, a novel approach that employed Granger causal modeling to assess the temporal and directional relationships between cortical arousals and leg movements15. That study revealed that textile-based capacitive sensors showed stronger temporal and spectral coupling with EEG-theta oscillations than inertial sensors, and more accurately identified expert-labeled cortical arousals. These findings support the hypothesis that leg movements and cortical arousals are driven by coordinated activity within a shared central arousal system. The current study builds upon this work by incorporating PPG and temperature sensors into the previously studied system and focusing exclusively on inertial sensors for movement detection, as they were found to reliably capture arousal-related leg movements while avoiding the redundancy and implementation challenges associated with textile-based capacitive sensors. This setup allows extraction of heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) features that may offer additional insight into autonomic activation during sleep20,21,22.

Results

Sleep is composed of two main states: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. NREM includes three stages: N1, N2, and N3, which progress from light to deep sleep. These stages repeat in cycles throughout the night23. We began by examining the distribution of cortical arousals across sleep stages to establish a physiological context for the classification task. Arousals occurred most frequently during N2 sleep, with a mean proportion of 56.77% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46.14–67.40%), followed by N1 at 17.47% (95% CI: 8.15–26.79%), REM at 13.17% (95% CI: 4.43–21.90%), and N3 at 12.60% (95% CI: 7.17–18.02%), averaged across subjects. This distribution aligns with established sleep physiology: N2 sleep not only comprises a larger portion of total sleep time but also has a lower arousal threshold, making it more prone to cortical arousals due to its transitional nature between wakefulness and deeper sleep stages23. Similarly, the elevated rate of arousals during N1 reflects its light sleep status and proximity to wakefulness. Interestingly, we also observed notable levels of arousals during N3 and REM sleep, suggesting increased cortical arousal beyond the lighter stages. This pattern may support prior findings showing that adolescents with ADHD and learning disorders exhibit increased cortical arousal during N2 and N3 sleep, particularly in central and frontal brain regions24.

We quantified the ratio of windows with an arousal during epochs with versus without respiratory events, averaging equally across subjects to avoid overweighting longer recordings. For obstructive apnea, the proportion of windows containing an arousal during non-apnea epochs was 6.68% (95% CI 5.17–8.18%, N = 14) and increased to 26.8% (95% CI 1.31–52.3%, N = 8) during apnea epochs. For central apnea, the proportion of arousal windows during non-apnea epochs was 6.54% (95% CI 5.04–8.04%, N = 14) and 16.4% (95% CI 0.65–32.2%, N = 12) during apnea epochs. The wider CIs for apnea-present conditions reflect that only subjects with ≥ 1 apnea epoch contribute to those estimates; notably, 6 of the 14 subjects had no obstructive-apnea epochs and 2 had no central-apnea epochs. Consistent with this, apnea prevalence in the analysis windows was low across subjects; 0.53% of windows for obstructive apnea (95% CI 0.15–0.92%, N = 14) and 0.85% for central apnea (95% CI 0.23–1.47%, N = 14).

To enable real-time detection of these arousal events using wearable data, we implemented and evaluated machine learning models designed to classify arousals from multimodal physiological signals. We evaluated the performance of three machine learning classifiers: Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and Random Forest for detecting cortical arousals based on multimodal physiological data from a leg-worn wearable device on full cohort of 14 children with ADHD, a population known to experience elevated levels of sleep fragmentation and frequent cortical arousals6. We chose these models to represent different levels of complexity and explainability: Logistic Regression as a simple linear baseline, Random Forest as a robust ensemble method, and XGBoost as a state-of-the-art gradient boosting algorithm. The results of model performance are summarized in Table 1, including class-wise precision, recall, F1-score, Receiver Operating Characteristic – Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC), and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC).

For context, the baseline AUPRC expected from random guessing equals the arousal prevalence (~ 0.07). All models substantially exceed this baseline, confirming that they successfully learned discriminative patterns beyond chance despite the class imbalance. Among the classifiers, Random Forest achieved the best overall performance (ROC-AUC = 0.94, AUPRC = 0.55) with a balanced precision–recall profile and was therefore selected for all subsequent analyses.

Feature importance

Figure 1 presents the ranked list of the most important features contributing to cortical arousal classification, as determined by the Random Forest model. These features were predominantly derived from accelerometer and gyroscope signals, with a smaller contribution from HR and HRV metrics. The most important features included statistical, energy-based, and entropy-related measures. Importantly, standard deviation, root mean square (RMS), maximum, and range from the x-axis of the accelerometer appeared prominently in the ranking. This suggests that lateral leg movement (x-direction) plays a critical role in arousal episodes, consistent with biomechanical patterns observed during limb movement–related arousals.

Entropy-based features such as spectral entropy from both accelerometer and gyroscope signals were also among the top-ranked predictors. These features reflect the signal complexity or irregularity during sleep and are useful for capturing subtle variations in movement associated with arousals. Similarly, RMS AUC (Root Mean Square Area Under the Curve) quantifies cumulative signal energy, which is often elevated during microarousals due to brief bursts of leg activity.

Other contributing features included HRV-derived indices such as HRV Higuchi fractal dimension (HRV-HFD), HRV Cardiac Sympathetic Index (HRV-CSI), and HRV Fuzzy Entropy (HRV-FuzzyEn), all of which reflect beat-to-beat HRV complexity, physiological markers known to fluctuate during autonomic arousals25. However, they were less important than movement-based metrics, suggesting a stronger motor component to arousals in children with ADHD. Similarly, temperature-based features were not among the top-ranked predictors, indicating minimal relevance to arousal classification in this context.

In addition to feature rankings, we analyzed PPG signal quality across arousal categories. The mean PPG quality score was 0.818 (95% CI: 0.738–0.899) during non-arousal periods and 0.488 (95% CI: 0.420–0.556) during arousal events. This significant decline in signal quality during arousals suggests increased motion artifacts or sensor dropout, which may explain the lower importance of PPG-derived features in the final model.

Agreement with ground truth

Figure 2 shows the model prediction of the arousal rates against the true arousal rates (ground truth). In this study, arousal rate refers to the number of 60-second windows that contain at least one cortical arousal event, normalized per hour of total sleep time. The predicted rates exhibited a strong correlation with the ground truth, yielding a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

ρ = 0.89 (p = 2.00 × 10⁻⁵) and a Kendall’s τ = 0.76 (p = 3.95 × 10⁻⁵).

These results show a strong relationship, suggesting that the model successfully preserves subject-wise ranking in arousal frequency, which is crucial for estimating severity and comparing individuals.

The fitted linear regression line further supports the alignment between predicted and true values. The slope below 1.0 indicates underestimation at higher arousal rates, yet the close clustering of points around the line reflects consistency in the overall prediction trend. The regression slope was statistically significant (p < 0.01), with a 95% CI of [0.383, 1.050].

To further assess agreement, a Bland–Altman analysis was conducted (Fig. 3). This plot shows the differences between predicted and true arousal rates as a function of their average, both expressed in arousals per hour. The mean difference was + 0.88 arousals/hour (Predicted − True), indicating a slight overall tendency of the model to overestimate arousal frequency. The 95% limits of agreement ranged from − 1.40 to + 3.17 arousals/hour.

Temporal prediction patterns

To evaluate model behavior across time, we visualized prediction sequences for three subjects who showed distinct arousal patterns. Figure 4 shows minute-by-minute comparisons between predicted and true arousals across the sleep duration.

For Subject A (Fig. 4a), who exhibited frequent and widely distributed arousals, the model effectively captured both isolated and clustered events throughout the night. Minute-by-minute inspection showed that most predictions were temporally aligned with ground truth, with several pre-arousal predictions appearing within one to two minutes of labeled events.

Temporal prediction of cortical arousals. Predicted versus true cortical arousal events for three ADHD participants. Each subplot shows 1-minute window predictions across the sleep period (x-axis in hours). Blue crosses represent model-predicted arousals, and red circles indicate ground truth events.

In contrast, Subject B (Fig. 4b) presented arousals that occurred in distinct temporal clusters during the early and late portions of the recording. The model maintained high temporal precision, correctly identifying contiguous arousal periods while avoiding false positives during quiescent intervals. Subject C (Fig. 4c) exhibited a sparser distribution of arousals. The model’s predictions closely matched the few true events, with overclassification toward the end.

The agreement between predicted and true arousals is quantified using Arousals (Class 1) F1-scores: 0.62 (a), 0.68 (b), and 0.54 (c). These scores indicate strong model performance given the substantial class imbalance, where arousals make up only ~ 7% of the data. For context, random guessing would yield an F1-score near 0.07, making the observed values highly meaningful. These subject-level, minute-by-minute visualizations highlight the model’s adaptability to inter-individual variability in sleep and arousal patterns.

Error characterization and event-level visualization

Event-level inspection of Subject C (shown in Fig. 4.c) revealed that the model successfully detected the first two arousal-related activations (Fig. 5). Pred 1 (~ 2.0 h) coincided precisely with a manually scored EEG arousal, representing a true positive. Pred 2 (~ 2.5 h) also aligned with a distinct burst of accelerometer and gyroscope activity that was labeled by expert scorers, indicating another correctly identified event. In contrast, the subsequent EEG-labeled arousal near 2.6 h was not detected by the model, constituting a false negative. Beyond 3.0 h, the model generated one true positive and one false positive prediction. The false positive coincided with a brief episode of high motion amplitude, suggesting that transient movement artifacts may have contributed to an incorrect arousal classification. For clearer visualization, we focused the time window between 1.8 and 3.8 h, which captured representative examples of all event types; true positives, false negatives, and false positives; within a continuous and interpretable segment of the recording.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using multimodal wearable sensors and machine learning to detect cortical arousals during sleep, offering an accessible alternative to traditional in-clinic polysomnography. Among the tested classifiers, the Random Forest model achieved the best overall balance between recall and precision, with an AUPRC of 0.55; a substantial improvement over the random baseline (~ 0.07) given the low prevalence of cortical arousals (~ 7% of total windows). These results are consistent with Random Forest’s ability to model complex patterns, feature interactions, and imbalanced data. Its ensemble-based architecture and embedded feature selection likely contributed to its robustness in this multimodal sleep dataset. Compared to Logistic Regression, which assumes linear relationships, and XGBoost, which can be sensitive to hyperparameter tuning in small datasets, Random Forest proved particularly effective at capturing subtle, subject-specific arousal signatures.

Feature importance analysis further revealed that the most predictive signals were derived from accelerometry and gyroscope data, particularly features reflecting signal variability and complexity, such as root mean square amplitude, standard deviation, and spectral entropy. These findings are consistent with prior work suggesting that leg movements are linked with cortical arousals14,16,17. Entropy-based features likely captured the fragmented or irregular movement patterns characteristic of arousal events. In contrast, HR and HRV features extracted from PPG contributed less prominently to model performance. This outcome was expected, as the original sampling rate of 25 Hz may be insufficient for accurate HRV estimation. Prior work has shown that HRV metrics like Standard Deviation of NN Intervals (SDNN) and Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) require significantly higher sampling rates to ensure reliability, at least 50 Hz for SDNN and 100 Hz or more for RMSSD without interpolation26. Additionally, signal quality issues further limited the reliability of PPG-derived features. These noises, primarily motion artifacts and high-frequency noise, are inevitable in wearable-based health and well-being monitoring systems and can significantly impact peak detection accuracy27. In our dataset, the average PPG signal quality declined from 0.818 during non-arousal periods to 0.488 during arousal, indicating a consistent reduction in signal integrity during arousal events.

Interestingly, the model predicted more arousals than were annotated by experts, particularly in subjects with sparse arousal profiles (Subject C). Rather than representing pure false positives, these predictions may reflect physiological events, such as sub-threshold arousals or autonomic activations, that were not captured by EEG-based criteria. This suggests that wearable sensors may detect some physiological markers of sleep disruption that fall outside the boundaries of current clinical scoring systems. Indeed, prior research has shown that physiological changes surrounding arousal events can be significant, often extending beyond the boundaries of EEG-defined arousals28,29. These findings highlight how machine learning and wearables can improve sleep assessment beyond conventional methods. The use of fixed 60-second windows may also have contributed to these discrepancies by grouping multiple arousals into a single segment. While some predicted arousals occurred outside manually labeled EEG events, inspection of the corresponding sensor data revealed short-lived motion bursts and physiological fluctuations that may represent autonomic or subthreshold arousals described in prior work. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that other false positives may arise from benign movement or stage transitions.

Despite the model’s overall strong performance, its AUPRC of 0.55 indicates that there remains substantial room for improvement in sensitivity and temporal precision. Event-level inspection of Subject C (Fig. 5) confirmed that the model accurately detected the first two arousal-related activations but missed a subsequent EEG-labeled event, with one additional false positive likely caused by transient movement artifacts. These observations illustrate that while the Random Forest classifier can identify clear multimodal arousal signatures, it may struggle to generalize across variations in arousal intensity and morphology. The use of fixed 60-second analysis windows likely introduced temporal smoothing. Future iterations should incorporate sequence-aware architectures, such as convolutional–recurrent or attention-based networks, to better capture contextual dependencies and subtler temporal dynamics.

Although the cohort size was modest (N = 14), several design choices were implemented to ensure sufficient statistical power and generalizability. Subject-level cross-validation and recursive feature elimination helped reduce overfitting, while the large number of per-window observations (> 6,000) supported stable model training and evaluation. While current results demonstrate the feasibility of multimodal arousal detection, future work should focus on improving both sensitivity (reducing false negatives) and specificity (minimizing false positives) through expanded data collection and model refinement in the next phase.

Lastly, our subject-independent and interpretable framework provides minute-level temporal precision, making it suitable for clinical applications that require generalizable detection. It shows promise for individuals with ADHD, a group often underserved by traditional sleep diagnostics. Pediatric restless legs syndrome, for example, can cause significant sleep disruption, behavioral issues, and impaired daytime functioning that mimic ADHD symptoms30,31. While ADHD’s recognized subtypes (inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined) are well-described, their association with distinct sleep profiles remains unclear, highlighting the need for detailed pediatric sleep assessment32. Refined at-home monitoring could help identify specific sleep disorders and support more personalized, subtype-targeted treatments for pediatric ADHD. Building on these findings, this work presents multiple opportunities for future development. Priorities include expanding to larger and more diverse datasets, using deep learning to model long-range patterns, and incorporating continuous arousal scoring to reflect subtle physiological changes. Real-world feedback such as sleep staging, user experiences, and device usability will be vital for transforming this research into a practical home-based health solution. Ultimately, these efforts aim to bring clinical-quality sleep analytics into everyday environments through smart and accessible wearables.

Conclusion

This study presents a non-invasive, wearable-based framework for detecting cortical arousals using multimodal physiological signals from a leg-worn device. Among the classifiers evaluated, the Random Forest model achieved the best overall performance, with a ROC-AUC of 0.94 and an AUPRC of 0.55, demonstrating strong agreement with expert-labeled EEG arousal annotations. Key predictive features, such as leg movement variability and signal entropy, support the role of movement-related physiological signals as markers of central arousals. These findings demonstrate the potential of systems like RestEaze™ for clinically meaningful, at-home sleep monitoring. Future work should include larger, more diverse populations and explore continuous arousal scoring to enhance clinical relevance.

Methods

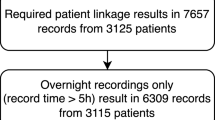

Participants and data acquisition

Fourteen community-living children (7 males, 7 females) between the ages of 6 and 16 years (mean ± SD = 11.54 ± 3.85 years) participated in the study. All participants met inclusion criteria defined for community-living males and females between 5 and 18 years of age with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of ADHD based on structured interview and/or the ADHD Rating Scale-5 (ADRS-5). ADHD subtype information was not available for these participants; however, it is important to note that subtype classification is considered developmentally unstable and may vary with age rather than reflecting fixed diagnostic categories. Additional inclusion requirements included a positive screen for the B, E, and A components of the BEARS sleep screening tool (Bedtime, Excessive daytime sleepiness, Awakenings), the ability to provide informed consent or assent with caregiver proxy, and the availability of a family caregiver to assist with data collection using the mobile application. Exclusion criteria included neurological disorders associated with extrapyramidal signs or symptoms and acute, unstable, or unmanaged medical conditions that could influence sleep patterns. These criteria ensured a well-characterized ADHD cohort while minimizing confounding medical factors that might affect sleep physiology. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) or other chronic comorbidities were not specifically included or excluded, but children with unstable or unmanaged medical conditions were screened out. Consequently, the sample represented generally healthy children with ADHD who exhibited sleep disturbance symptoms suggestive of restless legs syndrome (RLS) or frequent nocturnal arousals.

Each participant underwent a full overnight polysomnography according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) standards while concurrently wearing the RestEaze™ leg-worn wearable. Cortical arousals were manually scored by trained technicians from EEG recordings using AASM criteria, and all scorings were reviewed by a board-certified sleep physician. The manually scored EEG-based arousals served as the ground truth labels for wearable-based model training and evaluation.

Physiological and movement data were collected from these participants using the RestEaze™ Movement Analyzer, a wireless, leg-worn wearable designed for non-intrusive sleep monitoring and arousal detection. More details about the RestEaze™ can be found in previous publication18. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the RestEaze™ device integrates multiple synchronized sensors:

-

A 3-D accelerometer and 3-D gyroscope embedded within an inertial measurement unit (IMU) for leg movement and orientation tracking,

-

A PPG sensor for capturing cardiovascular dynamics, and.

-

Object and ambient temperature sensors for thermal signature during sleep.

The accelerometer (X, Y, Z axes), gyroscope (X, Y, Z axes), and PPG channels (IR, red, green LEDs) were all sampled at 25 Hz, providing high-resolution capture of biomechanical and cardiovascular signals. Temperature data was sampled at 0.2 Hz, appropriate for monitoring slow-changing thermal conditions.

This setup enables continuous, multimodal recording throughout the night, capturing both fine-grained leg movements and physiological fluctuations associated with cortical arousals. Across the 14 participants, the average total sleep time was approximately 7.25 h per subject, totaling 101.5 h of recorded sleep data. Data collection was conducted during natural sleep in a home or clinical setting.

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all relevant ethical guidelines and regulations, including obtaining informed consent from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

A total of 169 quantitative features were extracted across accelerometer, gyroscope, PPG, temperature, and HRV-derived signals. Inertial features included statistical, spectral, and energy descriptors (mean, standard deviation, variance, skewness, kurtosis, dominant frequency, spectral entropy, RMS amplitude, and RMS area) computed for each of the three motion axes (X, Y, Z) to capture directional asymmetries in leg movements. PPG features captured waveform morphology (skewness and kurtosis), while thermal features reflected both object and ambient temperature variability. HR and HRV features spanned time-, frequency-, and nonlinear-domain indices (e.g., SDNN, RMSSD, LF/HF ratio, DFA, MFDFA, entropy, and fractal dimensions). To mitigate the curse of dimensionality and reduce overfitting, a feature selection pipeline combining recursive feature elimination (RFE) and cross-validation–based ranking was applied, retaining the 30 most informative features for model training. A complete list of all extracted features, grouped by modality, is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Cortical arousals rate

Cortical arousals (ground truth) were identified and scored according to the guidelines set by the AASM33, which define arousals as abrupt shifts in EEG frequency, including alpha, theta, or activity exceeding 16 Hz, that last for at least 3 s and occur after a minimum of 10 s of uninterrupted sleep20. Arousal rate was calculated as the number of 60-second windows labeled with at least one cortical arousal event, normalized per hour of total sleep time. Specifically, if any arousal occurred within a given 60-second segment, the entire window was labeled as an arousal window (Class 1). The resulting arousal rate, expressed in arousal windows per hour, provides a temporally consistent metric for comparing arousal frequency across individuals.

In addition to cortical arousals, sleep stages, and limb movements were scored manually by trained technicians according to the AASM guidelines33. Bilateral limb movement events were also manually annotated, whereas leg movement channels were scored using an automated algorithm via the Sleepware G3 platform (Philips Respironics, US). Final scoring was reviewed and confirmed by a board-certified sleep physician and AASM fellow.

Preprocessing and feature generation

All raw sensor signals were processed using a unified preprocessing pipeline (see Fig. 6), which included filtering, segmentation into 60-second non-overlapping windows, and modality-specific feature extraction. The choice of a 60-second window was guided by the need to balance temporal resolution with physiological interpretability. Each one-minute segment contains sufficient cardiac cycles (typically 60–100 beats) to allow reliable estimation of HR and HRV, while also being short enough to detect changes in physiological state over time.

For the PPG signal, the preprocessing began with upsampling to 200 Hz using linear interpolation. This step was essential for achieving the temporal resolution required for accurate peak detection and compatibility with feature extraction functions that assume higher sampling rates. Several methods did not perform at the native 25 Hz resolution, especially those involving frequency-domain HRV metrics. The upsampled signal was then bandpass filtered between 0.2 and 5 Hz using a Butterworth filter to remove baseline drift and suppress motion artifacts. The filter was implemented in Python 3.11 using the butter and filtfilt functions from the scipy.signal module, which apply zero-phase forward and reverse filtering to avoid phase distortion34.

Following filtering, we evaluated several peak detection strategies to identify heartbeats from the PPG waveform. Among these, the ppg-findpeaks function from the NeuroKit2 library35 provided reliable results in terms of peak timing consistency and robustness to signal noise. Figure 7 shows the effects of preprocessing: the top panel displays the raw PPG signal with notable baseline fluctuations (Fig. 7a), the middle panel shows the filtered waveform with clearly resolved peaks (Fig. 7b), and the bottom panel plots the computed PPG signal quality over time (Fig. 7c). This quality metric, ranging from 0 to 1, reflects the reliability of the signal for physiological analysis.

Once peaks were detected, HR and HRV features were extracted from each 60-second window. HR metrics included minimum, maximum, and mean HR. HRV features encompassed time-domain measures (e.g., RMSSD, SDNN), frequency-domain indices (e.g., low-frequency/high-frequency ratio), and nonlinear metrics such as entropy, coefficient of signal irregularity, coefficient of variation of intervals, and fractal complexity (e.g., Higuchi fractal dimension).

PPG signal preprocessing and peak detection. The top panel (a) shows the raw LED green PPG signal, which contains low-frequency drift and movement-related noise. The middle panel (b) displays the same signal after linear interpolation to 200 Hz and bandpass filtering (0.2–5 Hz). The bottom panel (c) shows the corresponding PPG signal quality over time, with values closer to 1 indicating cleaner, more reliable signal segments.

Signals from the 3-D accelerometer and 3-D gyroscope were high-pass filtered with a cutoff frequency of 0.2 Hz to reduce low-frequency drift and artifacts. Each axis (X, Y, Z) was segmented into non-overlapping 60-second windows and processed to extract statistical features (mean, standard deviation, variance, skewness, kurtosis, minimum, maximum, and range), signal energy features (RMS and AUC), and spectral characteristics (dominant frequency and spectral entropy). Object and ambient temperature signals were not filtered but were similarly segmented into 60-second windows and processed to extract basic descriptive statistics, including mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and range.

All features across modalities were combined into a unified feature matrix indexed by timestamp and subject ID. Arousal labels were resampled into 60-second non-overlapping windows to match the feature segmentation. A window was labeled as an arousal event if it contained any arousal occurrence within its duration, ensuring sensitivity to even brief arousal activity. This binary labeling approach allowed the model to learn from both isolated and clustered arousal events, supporting robust temporal prediction. The dataset was imbalanced, with arousal windows (Class 1) comprising 6.6% of the data and non-arousal windows (Class 0) accounting for 93.4%, reflecting the rarity of cortical arousals during sleep.

Figure 8 shows the temporal evolution of these two features across a full night of sleep for a representative subject. Notably, arousal events tend to co-occur with spikes in accelerometer variability and drops in gyroscope entropy, suggesting more structured and intense leg movement during arousals. This visualization highlights the temporal coupling between movement features and arousal occurrences, demonstrating that arousal-labeled periods coincide with distinct bursts of movement activity, a key physiological basis for the model’s predictions.

Accelerometer and gyroscope feature trends across sleep. The top panel (a) shows the standard deviation of the X-axis accelerometer signal, reflecting variability in leg movement amplitude. The bottom panel (b) displays the spectral entropy of the Z-axis gyroscope signal, which quantifies the irregularity or complexity of rotational motion. Red markers indicate windows labeled as arousals, while blue markers denote non-arousal periods.

While this approach simplifies the classification task, it introduces a limitation: multiple arousals occurring within the same 60-second window are treated as a single event. This may underestimate the actual number of arousals in windows with dense activity. We initially experimented with shorter windows (e.g., 30 s) to capture finer temporal dynamics. However, this led to increased false positives, likely because pre- and post-arousal changes over the signals extended beyond the arousal itself. Thus, the 60-second window length was selected as an optimal trade-off between capturing relevant signal changes and maintaining specificity. Additionally, arousals that spanned multiple windows, a potential source of edge effects, were observed in approximately 10% of cases. Given that most arousals lasted 8 to 12 s, this level of boundary overlap was considered acceptable within the 60-second segmentation framework.

Machine learning framework and feature selection

We evaluated and compared the performance of three classifiers:

Logistic regression

As a baseline, we trained a Logistic Regression model with L2 regularization (Ridge penalty), which helps prevent overfitting and handles multicollinearity. The model was trained with subject-level z-scored features, class balancing, and LOOCV. Hyperparameters, including the regularization strength, were tuned using RandomizedSearchCV with 50 randomized iterations. While it offers greater interpretability, it lacks the capacity to model nonlinear interactions present in physiological time-series data.

Gradient-boosted decision tree model (XGBoost)

We also implemented XGBoost, a high-performance gradient-boosted decision tree model that incorporates both first- and second-order gradients. We tuned hyperparameters including learning rate, tree depth, subsampling rate, and L1/L2 penalties using RandomizedSearchCV with 50 randomized iterations. All training followed the same LOOCV protocol as the previous model.

Bagged tree ensemble model (Random forest)

We used a Random Forest classifier, known for its robustness to noise, ability to model nonlinear relationships and embedded feature importance analysis. Hyperparameters were optimized using RandomizedSearchCV with 50 randomized iterations. Tuned parameters included the number of trees, maximum depth, minimum samples per split and leaf node, and feature subsampling ratio. All training followed the same LOOCV protocol as the other models. The best-performing hyperparameters for each model, selected based on cross-validation performance across folds, are summarized in Table 2. Importantly, all hyperparameter tuning was conducted strictly within the training folds of each LOOCV iteration using an inner GroupKFold cross-validation. The left-out subject in each iteration was never used during hyperparameter optimization and remained completely unseen until final evaluation.

To account for inter-individual variability in physiological signals, all features were standardized per subject using z-score normalization. Columns with excessive missingness were removed, and the remaining missing values were imputed using subject-level k-nearest neighbors36. This method estimates missing values by averaging the feature values from the most similar observations in the dataset. Dimensionality reduction and feature selection were performed using Recursive Feature Elimination37 within the training folds to retain only the most informative features for classification.

A LOOCV scheme was used, where each subject was held out in turn as the test fold while the remaining subjects were used for training. This approach ensured strict subject-level separation and prevented data leakage, supporting robust evaluation of model generalizability.

To address the natural class imbalance between arousal and non-arousal events, a two-step resampling strategy was applied within each training fold. First, Tomek Links38 were removed to clean the decision boundary, followed by Random Undersampling39 to balance the class distribution during model fitting. As a sensitivity analysis, we also trained class-weighted models (XGBoost with scale_pos_weight; Random Forest with class_weight=’balanced’) and observed performance comparable to the Tomek-links + undersampling pipeline, so we retained the latter as our primary approach. Importantly, the held-out test subject was never undersampled, preserving the original data distribution for evaluation. Thresholds for classification were selected based on the precision-recall curve computed on the raw (non-resampled) version of the training data, ensuring that decision thresholds reflected realistic class ratios. The selected threshold was then applied to the test fold.

Together, these classifiers enabled direct performance comparisons. The outputs were evaluated using window-based overlap metrics and correlation analyses, described in the next section.

Model comparison and evaluation

Model performance was assessed using both classification-based metrics and agreement-based statistical analyses, with careful consideration given to subject-level separation through LOOCV. For each model, the area under the ROC-AUC and the AUPRC were computed to quantify overall discriminative ability, with AUPRC providing a more informative measure of performance under class imbalance. In addition, precision, recall, and F1-score, defined in Eq. (1) through (3), were calculated separately for arousal (Class 1) and non-arousal (Class 0) classes on a per-window basis. These equations quantify the performance of the model in different aspects:

To ensure equal contribution from each subject and prevent performance estimates from being skewed by subjects with longer recordings or more events, all metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) were first computed individually for each left-out subject in the LOOCV framework. The final reported values (Table 1) represent the mean of per-subject metrics, formalized as:

Where:

\(\overline{M}\) Subject-averaged metric (e.g., precision, recall, F1-score, ROC-AUC, AUPRC).

S: Total number of subjects.

In addition to discrete classification metrics, we evaluated the agreement between predicted arousals and ground truth arousals across subjects. The predicted arousal rate for each subject, defined as the number of arousal events per hour of total sleep time, was compared with the true arousal rate using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) and Kendall’s tau (τ) to assess monotonic relationships. Agreement between predicted and true arousal rate were further examined using Bland–Altman analysis40, which visualizes the bias and limits of agreement between model estimates and expert-scored references.

Feature importance analysis

After model training and evaluation, we analyzed feature importances using the Random Forest model trained on the entire dataset to capture generalizable patterns across all subjects. Random Forest determines feature importance by evaluating the total decrease in node impurity, such as Gini impurity, each feature contributes across all decision trees in the ensemble. Features that result in larger impurity reductions when used for splitting are considered more important41. This approach allows the model to naturally account for nonlinear relationships and feature interactions. To enhance interpretability and reduce noise from low-importance variables, we selected the top ranked features for post hoc analysis. This number was chosen empirically: including more than 30 features resulted in only marginal improvements in classification performance while increasing model complexity and risk of overfitting. The selected features represented a balanced trade-off between performance and interpretability and were used in downstream visualizations and interpretation.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the senior author (NB) on reasonable request and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’ approval.

Abbreviations

- AASM:

-

American academy of sleep medicine

- ADHD:

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CSI:

-

Cardiac sympathetic index (HRV-derived)

- FuzzyEn:

-

Fuzzy entropy (HRV-derived)

- HRV:

-

Heart rate variability

- HFD:

-

Higuchi fractal dimension (HRV-derived)

- LOOCV:

-

Leave-one-subject-out cross-validation

- PPG:

-

Photoplethysmography

- REM:

-

Rapid eye movement

- SDNN:

-

Standard deviation of NN intervals

References

Morgan, B. J. et al. Neurocirculatory consequences of abrupt change in sleep state in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 80, 1627–1636 (1996).

Xue, Y. et al. Durative sleep fragmentation with or without hypertension suppress rapid eye movement sleep and generate cerebrovascular dysfunction. Neurobiol. Dis. 184, 106222 (2023).

Chouchou, F. et al. Sympathetic overactivity due to sleep fragmentation is associated with elevated diurnal systolic blood pressure in healthy elderly subjects: the PROOF-SYNAPSE study. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2122–2131 (2013).

Cappuccio, F. P., Cooper, D., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P. & Miller, M. A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Heart J. 32, 1484–1492 (2011).

Duan, D., Kim, L. J., Jun, J. C. & Polotsky, V. Y. Connecting insufficient sleep and insomnia with metabolic dysfunction. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1519, 94–117 (2023).

Wajszilber, D., Santiseban, J. A. & Gruber, R. Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 10, 453–480 (2018).

Lal, C., Strange, C. & Bachman, D. Neurocognitive impairment in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 141, 1601–1610 (2012).

Owens, J. A. A clinical overview of sleep and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry J. Acad. Can. Psychiatr Enfant Adolesc. 18, 92–102 (2009).

Kushida, C. A. et al. Practice parameters for the indications for polysomnography and related procedures: an update for 2005. Sleep 28, 499–521 (2005).

Dement, W. & Kleitman, N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 9, 673–690 (1957).

Gerstenslager, B. & Slowik, J. M. Sleep Study. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Lee, Y. J., Lee, J. Y., Cho, J. H., Kang, Y. J. & Choi, J. H. Performance of consumer wrist-worn sleep tracking devices compared to polysomnography: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 21, 573–582 (2025).

Lee, T. et al. Accuracy of 11 Wearable, Nearable, and airable consumer sleep trackers: prospective multicenter validation study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 11, e50983 (2023).

Bogan, R. K. Effects of restless legs syndrome (RLS) on sleep. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 2, 513–519 (2006).

Bansal, K. et al. A pilot study to understand the relationship between cortical arousals and leg movements during sleep. Sci. Rep. 12, 12685 (2022).

Cortese, S. et al. Restless legs syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review of the literature. Sleep 28, 1007–1013 (2005).

Ferri, R. et al. Heart rate and spectral EEG changes accompanying periodic and non-periodic leg movements during sleep. Clin. Neurophysiol. 118, 438–448 (2007).

Bobovych, S. et al. Low-power accurate sleep monitoring using a wearable multi-sensor ankle band. Smart Health. 16, 100113 (2020).

Jha, A. et al. Pilot study: can machine learning analyses of movement discriminate between leg movements in sleep (LMS) with vs. without cortical arousals? Sleep. Breath. 25, 373–379 (2021).

Li, A., Chen, S., Quan, S. F., Powers, L. S. & Roveda, J. M. A deep learning-based algorithm for detection of cortical arousal during sleep. Sleep 43, zsaa120 (2020).

Pitson, D. J. & Stradling, J. R. Autonomic markers of arousal during sleep in patients undergoing investigation for obstructive sleep apnoea, their relationship to EEG arousals, respiratory events and subjective sleepiness. J. Sleep. Res. 7, 53–59 (1998).

Somers, V. K., Dyken, M. E., Mark, A. L. & Abboud, F. M. Sympathetic-nerve activity during sleep in normal subjects. N Engl. J. Med. 328, 303–307 (1993).

Patel, A. K., Reddy, V., Shumway, K. R., Araujo, J. F. & Physiology Sleep Stages. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Ricci, A. et al. Association of a novel EEG metric of sleep depth/intensity with attention-deficit/hyperactivity, learning, and internalizing disorders and their pharmacotherapy in adolescence. Sleep 45, zsab287 (2022).

Olsen, M. et al. Automatic, electrocardiographic-based detection of autonomic arousals and their association with cortical arousals, leg movements, and respiratory events in sleep. Sleep 41, zsy006 (2018).

Béres, S. & Hejjel, L. The minimal sampling frequency of the photoplethysmogram for accurate pulse rate variability parameters in healthy volunteers. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 68, 102589 (2021).

Kazemi, K., Laitala, J., Azimi, I., Liljeberg, P. & Rahmani, A. M. Robust PPG peak detection using dilated convolutional neural networks. Sensors 22, 6054 (2022).

Bonnet, M. H. et al. The scoring of arousal in sleep: reliability, validity, and alternatives. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. JCSM Off Publ Am. Acad. Sleep. Med. 3, 133–145 (2007).

Davies, R. J., Belt, P. J., Roberts, S. J., Ali, N. J. & Stradling, J. R. Arterial blood pressure responses to graded transient arousal from sleep in normal humans. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985 74, 1123–1130 (1993).

Cameli, N. et al. Restless sleep disorder and the role of iron in other sleep-Related movement disorders and ADHD. Clin. Transl Neurosci. 7, 18 (2023).

Martins, R. et al. Sleep disturbance in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. Sleep. Sci. Sao Paulo Braz. 12, 295–301 (2019).

Lazzaro, G., Galassi, P., Bacaro, V., Vicari, S. & Menghini, D. Clinical characterization of children and adolescents with ADHD and sleep disturbances. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-024-01921-w (2024).

Berry, R. B. et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). J. Clin. Sleep. Med. JCSM Off Publ Am. Acad. Sleep. Med. 13, 665–666 (2017).

Gommers, R. et al. scipy/scipy: scipy 1.9.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6940349 (2022).

Makowski, D. et al. NeuroKit2: A python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods. 53, 1689–1696 (2021).

Pedregosa, F. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. (2011).

Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S. & Vapnik, V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 46, 389–422 (2002).

Tomek, I. Two modifications of CNN. two Modif. CNN (1976).

He, H. & Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 21, 1263–1284 (2009).

Martin Bland, J., Altman, D. G., Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 327, 307–310 (1986).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant #1R43MH133495-01A1 (NIH SBIR Phase I). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R43MH133495-01A1 (NIH SBIR Phase I). The funding agency was not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NB and CF conceptualized the research. MK and SK performed the research. NB supervised the research. MK, SC, and KB prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. YA and QD contributed to data processing and supported manuscript revision. GK and JB contributed to the discussion section and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JB, CF, and NB are shareholders of Tanzen Medical Inc., the company that developed the RestEaze™ device evaluated in this study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kucukosmanoglu, M., Conklin, S., Bansal, K. et al. Detection of cortical arousals in sleep using multimodal wearable sensors and machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 44089 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27739-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27739-7