Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of planogram compliance in convenience stores by proposing a scalable, automated shelf monitoring system deployed across over 7,000 7-Eleven stores in Taiwan. Traditional manual audits are labor-intensive, error-prone, and costly, creating a growing need for reliable, automated solutions. To address this challenge, the proposed system integrates computer vision and deep learning techniques into a unified pipeline capable of detecting shelves, recognizing products, and comparing shelf layouts against digital planograms through a customized alignment algorithm. The system further incorporates multi-image stitching to overcome spatial constraints and construct virtual shelves that closely replicate real-world environments, improving adaptability and accuracy. Three large-scale datasets were developed to support model training and validation: 15,232 images for shelf detection, 99,135 images for product detection, and 471 product categories averaging 210 images each for classification. Automated labeling and clustering processes were introduced to substantially reduce manual annotation time. Experimental results demonstrate that the YOLOv8-based detection models achieve exceptional precision and recall across all stages. For shelf detection, the model achieved 99.23% precision, 98.93% recall, and 99.41% mAP@50, while product detection reached 94.61% precision, 93.02% recall, and 95.7% mAP@50—both surpassing transformer-based alternatives such as Deformable DETR. ResNet101 and FAN-based Transformer models achieved 99.86% accuracy on real-world retail datasets, indicating strong model stability. In the few-shot experiments, the FAN-based model showed strong adaptability and generalization, maintaining high accuracy with only five samples per class and achieving 98.39% Top-1 and 99.48% Top-5 accuracy on unseen products, demonstrating excellent transfer learning and real-time recognition capability. The system offers high accuracy, scalability, and real-time efficiency, making it a strong alternative to manual audits and a driver of smart retail innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and motivation

In the competitive retail industry, product placement on store shelves plays a critical role in influencing consumer purchasing behavior1,2. Planograms are schematic tools used by retailers to design shelf layouts that aim to optimize product placement and create consistent shopping experiences across store locations3. These planograms can come in many forms, such as an image detailing how products are to be placed on a shelf or a text file listing the orders of products on each row. Adherence to these planograms, known as planogram compliance, is essential for effective inventory management, brand consistency, and customer satisfaction4,5. This study introduces a planogram compliance system to be used in 7-Eleven stores across Taiwan—a total of over 7,000 retail locations—which presents a great opportunity to test planogram automation methods at scale.

However, planogram compliance is a complex task due to the dynamic nature of retail environments: shelves are frequently restocked, customers and staff move products, and new items are regularly introduced. Traditional methods of verifying compliance involve manual audits, which are time consuming and error prone. Automated systems harnessing computer vision and machine learning offer a promising solution but face remarkable challenges.

Challenges in automated planogram compliance

Retail spaces often have multiple shelves, racks, and other spaces containing a wide variety of products. Given the possible differences in retail environments, even within a single location, several challenges must be considered when developing a planogram verification system, including the following:

Physical environment

In practical retail settings, automated planogram verification systems assume that an entire shelf can be captured within a single image. However, this often proves impossible due to space constraints, tight aisles, and varying shelf depths—limitations that previous studies largely overlooked. The Hyb‑SMPC research highlights that common issues such as nonfrontal viewpoints, uneven illumination, and cluttered product arrangements lead to partial or distorted visual data. When only fragments of the shelf are captured, critical portions of products—price tags, facings, or entire SKUs—may be absent or misaligned, undermining the system’s ability to detect items accurately and verify layout compliance. Consequently, compliance reports may be incomplete or misleading, reducing trust in automation and necessitating additional manual checks—defeating the purpose of using computer vision in the first place. This limitation underscores the urgent need for approaches that can seamlessly stitch multiple shelf segments, adjust for viewing angles, or dynamically adapt capture strategies, ensuring full coverage even in confined retail environments—an area largely ignored in earlier work6.

Scale variations

Retail environments are inherently complex and dynamic, characterized by wide variations in store layouts, shelf sizes, product dimensions, and stocking patterns across different locations and formats. Automated systems designed for tasks such as planogram compliance verification or inventory tracking must therefore operate reliably across these diverse scales. A system that performs well in one store configuration may struggle in another if it cannot adapt to differences in shelf height, product density, or image resolution. Moreover, real-time decision-making in retail hinges on the system’s ability to process inputs with minimal latency—regardless of scale—so that frontline staff can act on actionable insights without delay. To be operationally viable, these systems must integrate scale-invariant algorithms, adaptive detection models, and dynamic calibration techniques that ensure consistent performance across large and small retail spaces alike. Addressing scale variations is not just a matter of visual accuracy but a prerequisite for maintaining efficiency, consistency, and responsiveness in high-velocity retail operations.

These challenges require advanced machine learning models capable of accurate detection and fine-grained recognition in complex environments while maintaining real-time performance. Our proposed planogram compliance system can reliably manage many of these challenges.

Contributions

Planogram compliance systems have great potential for retailers if the challenges in Sect. Challenges in automated planogram compliance can be addressed. First, quickly determining whether products are placed correctly would allow store employees the time to devote to other tasks. Second, the proposed system can also currently detect out-of-stock items, with the future possibility of recommending alternative products, adding to the potential efficiency gains. Furthermore, large retailers might be interested in delivering a consistent shopping experience across its locations, and such a pipeline would allow the company headquarters to verify this scenario on a daily basis. This study introduces a scalable, real-time pipeline for planogram compliance verification that addresses the aforementioned challenges. The key contributions include the following:

-

(1)

Large-scale retail shelf detection, product detection, and classification datasets.

To develop the proposed pipeline, we collected and labeled large datasets using automated methods and manual supervision to create the most accurate results.

-

(2)

Multiple overlapping image support for limited-space scenarios.

The proposed system can support multiple images of a single shelf, each image containing a fraction of the total shelf, and consider it as a single shelf in the virtual shelf component. This system is useful when dealing with limited space in real-world retail environments, where narrow aisles or long shelves might not allow to capture the entire shelf at one time.

-

(3)

Planogram verification pipeline using virtual shelf mechanism.

The proposed system uses the Needleman–Wunsch7 algorithm to verify compliance in a robust manner, similar to Yücel et al.8,9, with the added flexibility of supporting multiple images for a single shelf.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. Problem statement and related work details the problem statement and discusses earlier works in the field. Section Data annotation describes the proposed datasets and the annotation process. Section Planogram verification system describes the planogram verification system in detail. Section Experimental setup and results presents experimental results. Section Conclusion and discussion discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the system derived from the experimental results and concludes the study with suggestions for future research.

Problem statement and related work

Detailed problem definition

Planogram verification, also known as planogram compliance, refers to comparing the actual product layout in a store shelf, captured in an image called a realogram by the end user, with the desired product layout described in a reference planogram. The problem is then to compare the product arrangement in a reference planogram, made beforehand, with the realogram to measure its adherence to the reference planogram. To perform this comparison, the products in the shelf image need to be detected, classified, and grouped in accordance with the row in which it appears on the shelf. Each of these steps would require a dedicated machine learning model. The verification procedure would compare each shelf row in the realogram with its corresponding row in the reference planogram, assigning a status to each product in the realogram such as correct, incorrect position, incorrect shelf, out-of-stock, etc. Once the comparison has been performed for each shelf row, feedback should be returned to the store employee so that necessary changes can be quickly made. Figure 1 shows how the planogram and realogram comparison difference report is presented. The goal of planogram compliance verification is to compare the realogram with the reference planogram and then pass the report back to the user for correction or storage for further processing.

Application scenario

As mentioned, the proposed system is intended to be used across many 7-Eleven stores, where a single shelf contain many rows of items. Each shelf should have a predefined planogram file describing the products that belong on that shelf and their ordering. For instance, a planogram file could be a comma-separated-values (.csv) file, where each line lists the items that should appear in that order in the corresponding row of a store shelf, or any other file format more convenient to the final application.

A store employee would use some electronic device to capture an image (or images) of a store shelf. Following the image capture, the store employee would send that image to be processed by the system, for example, via a mobile or web app. When the pipeline finishes calculating the planogram compliance, a description of the results can be returned to the user as appropriate. This process of capturing a shelf image and sending it to the pipeline would be repeated for each shelf that is desired, granting the existence of a planogram file. One of the main contributions of the present work is to support multiple images for a single shelf via the virtual shelf algorithm, for use in the common scenario when not enough space is available to capture the entire shelf in a store. Figure 2 shows how a shelf can be captured by more than one image, each containing a portion of the total rows. If two such images are received, the virtual shelf mechanism estimates the order of the images based on the number of matched products with the planogram. The user could thus comfortably capture as many images as needed for the shelf and still receive near real-time results.

This pipeline can also be customized for different retail locations. In our use case, the pipeline has planograms and has been trained on data corresponding to 25 shelves across several retail locations. Given that the same shelf could be stocked differently in different locations, we have generated a unique planogram for each shelf across actual retail locations. In the future, each store could have customized planograms and thus could have a shelf layout more suited for that location.

Existing solutions and limitations

Machine learning for use in retail has been an active research area for many years10 and can be considered an application of the broader areas of object detection and image classification. However, most of the literature focuses on detecting and/or classifying retail products and propose novel methods to this end, while only a few works combine planogram compliance into the picture.

Earlier detection and classification approaches use traditional feature detectors for retail product detection or classification such as SIFT11 and SURF12. While these feature detectors can perform well under some image transformations, such as scaling, lighting conditions and other factors commonly present in retail scenarios are enough to lower their performance. Methods such as NSURF13 and AB-SURF14 build on these feature detectors for retail product detection but they remain less robust than later deep learning-based approaches.

Deep learning-based methods take advantage of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which can learn more robust features across a single product image. Foundational CNNs15,16,17,18,19 paved the way for later image classifiers and object detection models applied to retail image detection and classification20,21. Some approaches combine object detection and classification with planogram compliance22. Pietrini et al.23 proposed an entire pipeline using image retrieval to identify products and localize products based on bounding box coordinates. Tonioni and Di Stefano24 pose planogram compliance as a subgraph isomorphism problem, building the graph by adding an edge between adjacent products. Laitala et al.25 instead used the RANSAC26 algorithm to find the most suitable compliance probabilistically. The most similar planogram compliance approaches to the proposed system are those of Yücel et al.8,9, both of which also use the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm to calculate compliance. The main differences between our pipeline and theirs are that ours supports more statuses for a single product, and we use deep learning shelf detection, object detection, and classification models, whereas they rely on more traditional feature detectors.

Summary

Enabling planogram compliance at scale requires a system that can accurately detect and classify products on shelves. Furthermore, it requires an algorithm that can correctly account for any edge cases, missing products, stacked products on shelves, and many other common edge cases in retail stores, all while making the system easy to understand and use for store employees. Furthermore, the system needs to deliver results quickly to store employees to make necessary adjustments. Earlier efforts in this space either use less flexible feature detectors (perhaps suitable for embedded devices but not for our scenario) or do not provide an end-to-end solution combining retail object detection and classification followed by planogram compliance. Our proposed system aims to fill this gap by developing a reliable and scalable solution that can be deployed across thousands of retail locations. To achieve this, enough data is needed to train the aforementioned detection and classification models.

Data collection and Preparation

The success of any machine learning model hinges on the quality and representativeness of the training data. Recognizing this, we curated three datasets, one for each step in our pipeline: shelf detection dataset, product detection dataset, and product classification dataset27. This section describes the datasets and data collection processes in detail. To ensure that our dataset captures real-world variation, all images were collected on-site at actual operational environments. Specifically, we obtained data from four distinct 7-Eleven stores, each representing different store sizes and layouts. For each location, our team personally performed data collection at different time points throughout each day, covering various periods over three consecutive days. During the collection process, we intentionally moved the camera and varied the viewpoints to include as many different angles, lighting conditions, and shelf states as possible. As a result, the constructed dataset inherently contains a reasonable degree of visual diversity reflective of the realistic scenes encountered in practical deployment.

Dataset description

Shelf detection dataset

The first step in the planogram compliance pipeline is to analyze an image of a shelf for each row, obtaining the bounding boxes for each row. In the retail environments surveyed, shelves can vary greatly in appearance; some are refrigerated, and some contain hanging foods. The categories of products covered in the dataset include the following, and Fig. 3 shows the samples from the different shelf categories covered by the proposed dataset.

-

(1)

Cold drinks: Drinks such as milk cartons, tea, and various fruit juices, which need to be kept at cold temperatures.

-

(2)

Fresh foods: Chicken breasts, vegetables, and meats which hang rather than stand on a shelf.

-

(3)

Room temperature drinks: Sodas, teas, and other sports drinks.

-

(4)

Snacks: Many varieties of chips or cookies.

-

(5)

Instant noodles: Noodles of various shapes and sizes.

Given the large variety of products covered, the dataset must sufficiently cover every product category and shelf type to ensure detection models perform equally well on each type of shelf. The quantity and proportions of images in the training and testing datasets are described in Table 1. The images were manually annotated using an image annotation tool, and the bounding box coordinates of each shelf row saved. In this manner, the new dataset can be easily loaded into traditional object detection models.

Product detection dataset

In addition to the shelf detection dataset, we create a product detection dataset by annotating the bounding box for each product in the shelf images, shown in Table 2. The dataset was annotated using a pretrained object detection model and its outputs manually verified using a dataset annotation tool.

Product recognition dataset

In the proposed pipeline, once the shelves are detected and the products on each shelf are detected, the last step involves classifying the product into one of n categories. For that purpose, the final proposed dataset includes thousands of images of various retail products, obtained from the large amount of shelf images collected from real retail locations belonging to one of the largest retailers in Taiwan. In total, \(\:\text{N}=\) 471 categories are present in the dataset.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the recognition dataset, with the classes sorted by descending image counts. There are currently 99,135 product images, with an average of 210 images per class and a median of 165 images per class. The minimum number of images per class is 58 and the maximum is 1917.

Data annotation

Shelf and product detection datasets

Accurate annotations are vital for supervised learning models. We undertook a meticulous annotation process to ensure the quality of the data labels for the detection and recognition datasets. For the detection datasets, each image has its own annotation file, where each line describes the location of a detected object. In the shelf detection dataset, each annotation file corresponds to a shelf row in that image, whereas in the product detection dataset, each line corresponds to a detected product. Each line contains five numbers, resembling the following:

\({\mathbf{0}},{\mathbf{0}}.{\mathbf{492727}},{\text{ }}{\mathbf{0}}.{\mathbf{897019}},{\text{ }}{\mathbf{0}}.{\mathbf{793297}},{\mathbf{0}}.{\mathbf{190870}},\)

where the first number corresponds to the class of the item detected. The shelf and product detection datasets only have one class, “shelf” and “retail item,” respectively; thus, the first number will always be zero. The remaining four numbers are normalized coordinates, the first two of which indicate the center x and y coordinates, and the last two numbers indicate the height and width of the item’s bounding box.

The first iteration of the detection datasets was annotated entirely manually. Initial shelf and product detection models were trained on this manually labeled dataset and used to label subsequent images as the datasets grew. Manual inspection ensured the accuracy of the annotations.

Product classification dataset

To label the product classification dataset, we use an automated clustering method and then verify the results manually. Initially, shelf data are collected from each store in the form of images or videos, splitting up each frame in the case of videos. The resulting images are then run through pretrained shelf and product detection models, similar to the proposed pipeline described in Sect. Planogram verification system.

With the resulting product subregions of the image, a pretrained embedding model produces embeddings for each product image. A Bayesian optimization process takes the embeddings and produces optimal parameters to be used in a later clustering step. Dimensionality reduction methods such as PCA28 reduce the embedding size such that a clustering algorithm can more efficiently produce the corresponding clusters. The HDBSCAN29 algorithm generates the cluster from the image embeddings by building a minimum spanning tree from the embedding set, then finding the optimal \(\:{n}_{c}\) clusters based on the optimal parameters found earlier. Figure 5 shows the autolabeling process in detail.

The process results in an assignment of the products in the input images to clusters containing mostly products from the same class. A final manual inspection of the generated clusters can correct for any misclassifications. Although the process is not perfect and human intervention is still required throughout the process, generating datasets of the scale that we introduce would not have been feasible without the autolabeling process.

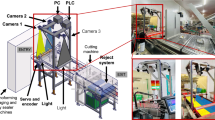

Planogram verification system

This section describes in detail the planogram verification system, shown in Fig. 6, starting with a description of the detection and recognition models compared in this study and ending with a detailed description of the planogram verification algorithm based on a virtual shelf representation. The planogram verification process relies on the output of the detection and classification models; thus, they are the first step in the system. This algorithm outputs the compliance report that is returned to the store employee.

Deformable detection transformer

In this section, we introduce the Deformable DETR (Detection Transformer)30 and YOLOv831 object detection models, which have been successful in many object detection tasks. The former is based on the popular Transformer32 architecture, while the latter represents the latest iteration in the long-established YOLO family. In recent years, the Transformer architecture has become a popular choice for many tasks due to its ability to model various relationships in a single sequence. First, we briefly describe the Transformer architecture, then describe the Deformable DETR architecture which we test in the proposed system. We conclude with a brief description of the YOLOv8 model.

A Transformer block is composed of a multihead self-attention module and a feedforward neural network. Inputs to a Transformer block can be a sequence of text or image patches33, but each modality type undergoes some type of initial embedding or projection. The inputs to the self-attention module are three matrices \(\:\text{Q},\text{K}\) and \(\:\text{V},\) where the first two matrices are representations of the input sequence, and \(\:\text{V}\) contains the information to be aggregated by the self-attention equation. This operation for a single attention head can be expressed as

where is \(\:{d}_{k}\) the dimensionality of the key and query matrices. Multihead self-attention blocks contain \(\:\text{h}\) attention heads, each learning different relationships between the input sequence elements and each having different linear projects \(\:{W}_{i}^{Q},{W}_{i}^{K},{W}_{i}^{V}\) for each attention head \(\:\text{i}\le\:h\). A positional encoding value is also added to each input element of the encoder and decoder blocks. The Deformable DETR30 model builds on the DETR4 work introducing transformers for object detection. Both models use a CNN backbone (e.g., ResNet5021 to extract feature maps from an image and obtain the key and query values for the transformer block from this feature map. Transformer models normally compare all the query elements with all the key elements, leading to a quadratic complexity on the size of these matrices. The deformable attention module introduced in this paper utilizes a reference point \(\:{\varvec{p}}_{q}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{2}\)as part of the query vector \(\:q\), which is compared with \(\:K\:\)reference points close to \(\:{\varvec{p}}_{q}\). Given \(\:M\) attention heads in each attention module, the deformable attention head is defined as

where \(\:{\varvec{W}}_{m}^{\varvec{{\prime\:}}}\:\)is the input projection matrix for the \(\:m\)-th attention head, \(\:{\Delta\:}{\varvec{p}}_{mqk}\:\)are the key offsets to be compared against \(\:{\varvec{p}}_{q},\:\)and \(\:\varvec{x}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{C\times\:H\times\:W}\:\)is a feature map coming from the backbone encoder. Given that the original DETR model struggles detecting smaller objects, they also introduce multiscale feature maps in the decoder. The decoder modules perform cross-attention and self-attention. The cross-attention module uses object queries, which are features that come from the backbone encoder as queries while the keys are the feature maps that come from the encoder. The encoder self-attention module also uses the object queries as the query and key values.

YOLO family application

The YOLO family of models have become a popular choice in computer vision, specifically with tasks that require real-time results17,34 because they are one-stage detectors, predicting bounding boxes and classifying the item with a single model. YOLOv831, being the latest YOLO model, makes some improvements on earlier architectures. Each YOLO model has three components: the backbone for feature extraction, the neck for feature fusion across feature map scales, and the head for predicting bounding box coordinates and object classes.

YOLOv8 uses CSPDarknet35 as the backbone, in which incoming feature maps are split into two parts, \(\:{X}_{1}\)and \(\:{X}_{2}\). The output at this stage will be

where \(\:{f}_{i}\:\)can be a series of operations such as convolutions, activations, etc. This arrangement can maintain rich feature representations while reducing the backbone’s computational overhead. The neck is based on a path aggregation network36, which aggregates features from multiple feature map scales by introducing a bottom-up flow. For a feature map with a given scale \(\:{p}_{i}\), this is achieved through

where \(\:{C}_{i}\) is an output feature map from the backbone, and \(\:{P}_{i+1}\) is a higher-level feature map. The head is split into two branches, one to handle object classification and another for regression. These heads are decoupled and do not rely on information from the other branch to avoid feature interference. Given the input feature map \(\:F\), the classification branch is defined as.

where \(\:\sigma\:\:\)indicates the sigmoid activation function, and \(\:{W}_{c}\) and \(\:{b}_{c}\) are a learned weight matrix and bias vector, respectively. The output for the regression branch is similarly given as

where \(\:{W}_{r}\) and \(\:{b}_{r}\) also represent a learned weight matrix and vector for the regression task, respectively. The binary cross-entropy loss function is used for the classification head, while the detection head is trained with the generalized intersection-over-union (GIoU) loss function37. This version of IoU considers also the smallest enclosing convex object between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes. YOLOv8 also uses an objectness loss, which evaluates the model’s confidence in detecting objects versus the background. The final loss function is a linear combination of the classification, detection, and objectness losses.

Now that both detection models have been introduced, we turn our attention to the planogram verification system architecture, which relies on the object detection models introduced here to calculate planogram compliance.

Planogram verification system

The system has an image or series of shelf images as inputs, runs the images through the model pipeline, and returns a compliance report to the user after the virtual shelf algorithm checks for compliance shown as Fig. 6.

The planogram compliance pipeline is responsible for taking the image or set of images \(\:\mathcal{I}=\left\{{I}_{1},{I}_{2},\dots\:,{I}_{n}\right\}\) of a shelf, forwarding the image data through the machine learning models and finally checking the compliance with the virtual shelf mechanism. Figure 6 describes the pipeline structure, inputs, and outputs of each component. Currently, the pipeline has three models: the shelf detection model\(\:\:f\), the product detection model \(\:g\), and product classification model \(\:h\). A single shelf image or a collection of images first arrives at the backend server via an HTTP request from the frontend mobile application, containing the image(s) needed for processing.

Regardless of whether there are one or more than one image in the request, the system processes each image individually and only matches the realogram shelf to a particular planogram shelf until the planogram compliance step. For example, suppose that there are two incoming images to be processed, one containing the top \(\:x\:\)shelves and the bottom image containing the remaining \(\:\left|\mathcal{S}\right|-x\:\)rows in a shelf, where \(\:\mathcal{S}\) is the set of product rows in the shelf, and suppose each image contains at least one shelf. The shelf detection model would see each incoming realogram image sequentially, identifying the product rows present in each image independently for the time being. In a similar way, the product detection and classification models would consider each image independently of the others, instead focusing only on the image at hand.

The shelf detection model is trained to detect entire product rows; thus, its output is a set of bounding box coordinates for what it detects to be the shelves in the image or a pair of coordinates (\(\:{x}_{1},{y}_{1},{x}_{2},{y}_{2})\) for each row \(\:{\mathcal{S}}_{i}\) in \(\:{I}_{i}\). Given that each shelf image is processed independently, we describe the process for a single shelf image. Given an incoming image \(\:I\), the shelf detection model will detect all the \(\:m\:\)shelf rows in \(\:S\) by

Cropped image regions obtained with the bounding box coordinates sj or the j-th shelf row form the input to the product detection model. We take each region of I defined by the bounding boxes in sj, denoted by \(\:I{\left.\right|}_{{s}^{j}}\), and feed it as input to the product detection model which outputs a list of coordinates corresponding to the shelf row Si given by

Now that we have the bounding boxes for each product in I grouped by the shelf row in which they appear, in a similar way, we take the cropped image region given by \(\:{p}_{j}^{l}\) or the l-th product in the j-th product row, and pass that image region to the classification model h. The output of the recognition model is a vector \(\:{c}_{j}^{l}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{C}\)containing the class probabilities of the product image crop:

We take the highest of these confidences as the class prediction. We also set a threshold for the classification confidence, where the product is marked as “unknown” if the highest confidence falls below that threshold. All the images received go through this process independently, and at the end remains the collection of products detected in each image. Once the system detects and classifies the products in all the images, the system combines each image’s detection and classification results into a single global shelf. However, these results might be initially unordered, which would require the virtual shelf mechanism to estimate a global shelf row ordering.

Virtual shelf mechanism

The virtual shelf mechanism mentioned throughout the study is an abstract representation of the shelf. A more abstract design facilitates the support multiple images per shelf because some shelves cannot be captured entirely in a single image in many stores. The virtual shelf is essentially a representation of the detected shelves and the products within those shelves. While the detection models output only the bounding boxes, the pipeline stores some additional fields for each shelf in a list defined as

where ImageId represents the index of the shelf image in which the i-th shelf was detected, GlobalShelfId counts how many shelves have been detected so far, ShelfBox are the shelf bounding boxes, DetectedData is a list of detected products on the shelf, and \(\:\mathcal{S}\) represents the total number of shelves detected in the series of images. The field Detected Data in \(\:{\mathcal{S}}_{i}\) is a list containing information about a detected product. The data structure for each detected product is as follows:

where label is the predicted class from the recognition model, position is the center coordinates in the shelf image, box denotes the product’s bounding box coordinates in the shelf image, confidence is the classification confidence also output by the recognition model, and \(\:{P}_{si}\) is the number of products detected in \(\:{\mathcal{S}}_{i}\). The position of the planogram determines where in the global shelf representation it is supposed to be located.

Planogram compliance verification algorithm

To match the detected shelves of multiple images to a single planogram representation, we have to estimate a global ordering of the shelves gathered from the incoming images. For a shelf row s, its ordering on the global shelf will be determined by the number of matching products it contains with the i-th row of the planogram. We form an initial estimate of which detected product row corresponds to each expected product row because the planogram compliance verification algorithm operates on single rows.

Ideally, the number of detected items in the shelf row matches the number of items in the planogram row. In this case, a simple one-to-one comparison is enough to measure the compliance; however, in case of different product quantities, a more precise algorithm is needed. This next step of discrepancy detection is based on the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm7, which was initially applied to find the divergence of DNA sequences. In checking the planogram compliance, the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm helps calculate the cost of aligning the planogram and realogram once the virtual shelf has been created and the shelves have been ordered. The algorithm uses dynamic programming to find correctly placed products, out-of-stock products, products in incorrect locations, and products on wrong shelves. It takes as input the labels of expected products on the i-th row Pexp and the labels of detected products on the shelf estimated to be the i-th row Pdet, so this algorithm only takes as input one shelf row at a time. Given the possible statuses of a product, we introduce our own penalty values shown in Table 3, which we set to constant values.

First, the algorithm evenly divides the shelf into d/nexp equal segments, where d is the shelf width given by the difference of x-coordinates and nexp is tne number of expected products in this row. The resulting blocks indicate sections where a product is expected on the shelf, although this can only be a rough approximation because products vary in dimensions.

The algorithm then constructs a two-dimensional matrix Aε Rnexp+1,ndet+1, where ndet is the number of detected products. We can think of aligning each item of Pdet along the top row and likewise align the items of Pexp along the first column. The first item a0,0 is set to 0, and the items along the first row a0,i and first column aj,0 are set as follows:

Figure 7 shown cell a2,2 is the minimum cost of out-of-stock products, extra products, or the other possible statuses, which depend on the distance d to box center Bi.

Next, we proceed to fill in the matrix A. At each value ai, j we first calculate the distance d between the i-th and j-th products, resulting in increased distances as we compare products that are further from each other. If Pidet = Piexp, we consider only the distance between these two products; otherwise, we consider whether the product was classified as unknown, in the incorrect position on the shelf, or whether the product is on the wrong shelf and add the appropriate penalty. In any case, we use d and add the appropriate penalty depending on the product status which can be determined by checks on the expected and detected product at that position. We call this initial value dp to simplify the notation. The final value ai, j can be written as

After setting each ai, j, the algorithm backtracks through the array to find the optimal alignment for both sequences. Starting from the bottom right element, the algorithm calculates the optimal alignment cost by measuring whether ai, j is the result of adding λoos or λep to ai−1,j and ai, j−1, respectively. Essentially, the algorithm traces the path back to the origin point, and at each ai, j, it records the local result at that stage. Algorithm 1 in the Appendix shows the pseudocode for our implementation of the virtual shelf based on the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm.

Our pipeline also has to consider some special conditions. Some of the item statuses, specifically the out-of-stock status, require special considerations. Out-of-stock items are also calculated by the gap size between the detected products and their bounding boxes. If the gap between the i-th and i + 1-th product in a row is larger than some threshold, an item is considered to be missing between them. Another special situation occurs when some types of retail items in one shelf row items are stacked on top of each other. Instant noodles, for example, which appear in flat, bowl-like containers are sometimes stacked two or three boxes high in the same product row. The pipeline considers such overlaps and checks whether all stacked products belong to the same class before considering them as a single product.

Experimental setup and results

To validate the proposed datasets collected from 7-Eleven stores in Taiwan, we design an experiment suite for the detection and classification datasets. Given that the planogram compliance verification algorithm relies on bounding boxes and product category information, the models must perform well on the data they encounter. For the shelf and product detection tasks, we compare leading object detection models YOLOv838 and Deformable DETR30 as representative CNN and Transformer-based models, respectively. For the detection experiments, we compare both training from scratch and fine-tuning models pretrained on the COCO39 dataset. This evaluation regime allows measuring whether our datasets allow for high-quality models and whether detection models can apply features learned from standard detection datasets to our own. For the classification tasks, we train an EfficientNet-B4 model and a ResNet101 model as representative CNN-based architectures and an NVIDIA Fan-based hybrid model40, on the basis of a Transformer32 architecture to compare against a newer and popular model architecture. To assess the model’s generalization capabilities, we partitioned the dataset on a store-level. Training set come from three 7-Eleven stores, while data from the fourth, unseen store was reserved for the test set. This approach ensures our evaluation is based on the model’s performance in a completely new environment.

Evaluation metrics

To gain a full understanding of our model performance, we report several metrics for our models. For the detection and classification models, we report the precision, recall, and F1 score, while we add the mAP@50 for our detection experiments and the accuracy for our classification experiments.

Shelf detection

We train both models using the hyperparameters described in Varghese et al.31 and Zhu et al.30, respectively. Table 4 shows the results product row detection on the proposed shelf detection dataset.

This result indicates a strong overlap between the features learned from the pretraining stage and our current dataset, enabling both models to bring over the features from COCO to the proposed shelf detection dataset. A possible reason for this could be the difference between a shelf and the objects commonly seen in COCO; however, the models still leverage their pretrained features and achieve high scores on the shelf dataset. Both the YOLOv8 models trained from scratch and fine-tuned on our datasets outperform the Deformable DETR in their respective categories. The fine-tuned YOLOv8 shows slight gains over the from-scratch version, suggesting the model can transfer knowledge gained during pretraining to our dataset. By contrast, Deformable DETR is negatively affected when fine-tuned versus trained from scratch on our dataset. In the future, larger training datasets could allow for improved performance from Deformable DETR.

Product detection

For the product detection experiments, we train a Deformable DETR model for 50 epochs, using hyperparameters described Zhu et al.30 on the NVIDIA TAO platform. For a comparison with a different model family, we also train a YOLOv8 model with a patience of five epochs, stopping the training process if the metrics do not improve above a threshold. Similar to the shelf detection experiments, we also compare the difference between models trained from scratch and models pretrained on COCO. We train the Deformable DETR mostly with the same hyperparameters described in30. Table 5 shows the detection results.

YOLOv8 outperforms Deformable DETR in from-scratch and pretrained scenarios. Both pretrained models show slight gains over their counterparts trained from scratch. However, the Deformable DETR models show a more noticeable drop overall compared with the YOLOv8 models in this experiment and the Deformable DETR models. Possible remedies for such Transformer-based models include further hyperparameter tuning and warmup epochs, which the TAO platform did not support for the Deformable DETR and which can be critical for Transformers, given their increased sensitivity to hyperparameters. Given the difference in size between the shelf and product detection datasets, a slight decrease in performance might be expected on the product detection experiment, but a more refined training pipeline could do much to increase the performance.

Product classification

In this section, we compare various classification models on the proposed classification dataset. To obtain a more representative comparison, we test two established CNN-based models EfficientNet-B4 and ResNet101 and newer Transformer-based architectures using a FAN-based hybrid model with a VIT-B33 backbone. We train the models for 100 epochs, and we use the Focal Loss41 function with γ = 2 to reduce the effect of easier samples on the model updates only for the CNN-based models. For the FAN-based model, we test using the original settings in Zhou et al.40.

To address the class imbalance, present in the product recognition dataset, as highlighted in Fig. 4, we employed weighted sampling strategy during model training. First, we utilized weighted sampling, designing the sampling probability for each class based on its frequency so that under-represented categories were sampled more frequently and over-represented ones less so. This approach ensures that each batch during training contains a more balanced class distribution, mitigating biases caused by data imbalance.

To address the limited diversity in our product recognition dataset—where many images of the same product were captured from similar angles due to typical store display practices—we implemented an extensive data augmentation strategy during model training. This regimen included a combination of random horizontal and vertical flips, rotations, affine transformations, perspective changes, and color jittering, all applied to the training images to artificially increase visual variety. Additionally, we employed random masking of rectangular regions following the method of Zhong et al.40 to further enhance data variation. These augmentation techniques were designed specifically to enrich the diversity of training samples and help the model generalize better by reducing the risk of overfitting to limited viewpoints or repetitive scenes in the original dataset. The results and the number of trainable parameters are shown in Table 6.

All three models—ResNet101, EfficientNet-B4, and the FAN-based hybrid model—achieved highly similar results on our testing dataset, with scores on key metrics consistently exceeding 99%. Although the FAN-based hybrid model demonstrated the best overall performance among the three, the margin is not statistically significant. As shown in Table 6, all models maintained high precision, recall, and F1 scores, indicating robust recognition capability even in the presence of a heavily imbalanced training dataset. This can be attributed to our adoption of weighted sampling and focal loss during training, which effectively mitigated class imbalance and enabled strong performance across all evaluation metrics.

Few-shot classification

7-Eleven stores frequently introduce new or limited-edition products, requiring constantly updated data. Rapidly deploying classification models to stores is crucial to maintain a robust system, and being able to reduce data collection costs would be greatly beneficial. This section along with zero-shot experiments in Sect. 5.6 aim to measure whether recognition models can still learn valuable information with scarce training data, a common situation in retail environments. Few-shot learning (FSL)42 is a subproblem in machine learning, where the training dataset contains only K labeled samples per class and N classes, where K is usually a small number such as 1 or 5.

Our experiments are conducted as follows: We randomly sample five images from each training class to create a five-shot subset of our training dataset and repeat this process three times for three five-shot splits of our datasets with N set as 471. We use models pretrained on ImageNet-1 K43 as the baseline and fine-tune each model for 15 epochs, replacing the final classification layer to match our dataset’s class number. As in44, the slight domain shift between ImageNet and our dataset might require a large initial learning rate for transfer learning. For the FAN-based hybrid model, we use three warmup epochs and reduce the number of augmentations. Table 7 shows the average accuracy on the three dataset splits and the standard deviation. Average accuracy and standard deviation when fine-tuning models on three randomly selected splits of the recognition dataset, where each class has five training samples. Testing was conducted on the unmodified testing dataset.

Among the three evaluated models, the FAN-based hybrid model delivered the highest few-shot accuracy at 98.33% with the lowest variance (± 0.03%), demonstrating exceptional generalization and robustness even with minimal labeled data. Its low standard deviation across multiple training splits highlights consistent performance, making it highly suitable for real-world retail deployment. The model’s hybrid architecture, which integrates Vision Transformers (ViTs) and attention mechanisms, enhances its ability to capture fine-grained visual distinctions, especially among visually similar products. EfficientNet-B4 also performed relatively well, achieving 87.75% accuracy with a moderate variance of ± 5.68%. Its compact design and efficient scaling contribute to its adaptability in data-limited settings; however, its performance lags behind the FAN-based model, suggesting that CNN architectures may be less effective in learning fine-grained distinctions under constrained data. By contrast, ResNet101 exhibited the lowest performance at 64.54% with the highest variance (± 11.39%), indicating sensitivity to class imbalance and limited generalization capacity. The substantial variability further suggests potential overfitting and instability when trained with only a few examples per class, limiting its reliability in practical few-shot scenarios.

Zero-shot recognition

We also measure each model’s ability to classify images from classes it has not encountered during training—a task known as zero-shot learning (ZSL). In contrast to FSL, ZSL involves no fine-tuning; instead, we apply pretrained models directly to the testing dataset, showing we could leverage pretrained models to our retail scenarios if needed. Following the procedure in Sect. 5.5, we use models pretrained on ImageNet1k and report top-1 and top-5 accuracies. To compute the top-1 and top-5 accuracies, we collect the output embeddings from the model’s penultimate layer and calculate the cosine similarity between each embedding pair. We increase the top-1 accuracy if the embedding’s nearest neighbor belongs to the same class, and the top-5 accuracy if any of the five closest samples belong to the same class. Given that we are not fine-tuning the backbone’s weights or training a linear classifier, the performance on this experiment might differ from the few-shot scenario. Table 8 shows the results on the classification dataset.

Overall, the pretrained models generalize well to the proposed classification dataset, further reducing the cost and effort to deploy models in retail environments. Even with many visually similar items in our dataset, features learned from other general datasets transfer effectively to our dataset. Although Transformer-based and CNN models perform well, the FAN-based hybrid model performs slightly better in the top-1 and top-5 accuracies, which could be highly valuable as the system scales to thousands of product categories.

Deployment and scalability analysis

To evaluate the practical scalability and efficiency of our planogram compliance system under realistic deployment scenarios, we conducted a series of throughput and load tests on our deployment environment. The deployment was carried out on a Google Cloud Platform (GCP) machine. Table 9 shows the detailed hardware specifications.

Table 10 summarizes the results of our load test experiments, in which the system was subjected to an increasing number of simultaneous requests. For each run, we recorded the total number of processed requests, total test duration, average duration per request, and the final response rate (RPS, responses per second).

It is important to note that the increase in RPS was not linear with the number of requests. As the workload increased, the RPS growth rate gradually slowed, exhibiting a pattern similar to logarithmic growth. This reflects the system approaching saturation, where further increases in request volume resulted in diminishing gains in throughput. In addition, during model deployment we adopted NVIDIA’s Tensor RT inference acceleration engine, which optimizes trained models through techniques such as layer fusion, precision calibration, and memory optimization to achieve faster and more efficient execution on NVIDIA GPUs. With Tensor RT, our system’s response speed was boosted by an average of 1.5× to 2×. Overall, these results confirm the practical scalability and robustness of our solution for deployment in high-traffic retail environments.

Conclusion and discussion

Conclusion

This study presents a comprehensive and scalable framework for real-time planogram compliance verification using computer vision and virtual shelf mechanisms, specifically designed for deployment across more than 7,000 7-Eleven stores in Taiwan. Through the integration of deep learning-based shelf detection, product detection, and classification models, alongside a Needleman–Wunsch-based compliance algorithm, the system effectively addresses key challenges in retail automation, such as limited imaging conditions, product occlusion, real-time inference demands, and human error. Experimental validation and findings are as follows:

Shelf detection

The YOLOv8 model, fine-tuned on the custom dataset, achieved outstanding performance (Precision: 99.23%, Recall: 98.93%, mAP@50: 99.41%), surpassing Deformable DETR. This result underscores YOLOv8’s superior generalization ability and robustness to the structural variance of shelves in convenience stores.

Product detectionh

Again, YOLOv8 outperformed Deformable DETR, reaching 94.61% precision and 95.73% mAP@50 in the pretrained setting. The experiment highlights YOLOv8’s architectural efficiency in dense product environments. The relatively poor performance of Deformable DETR (Precision: 64.93%, Recall: 73.36%) reveals a potential mismatch between its Transformer-based architecture and the high spatial granularity required in retail images.

Product classification

Among CNN and Transformer-based architectures, the FAN-based hybrid model delivered the highest accuracy (99.86%) and outperformed ResNet101 and EfficientNet-B4. The result indicates that Transformer-based models with visual token embedding provide a stronger representation capability for diverse, fine-grained retail product classes.

Few-shot learning

The FAN-based hybrid model exhibited remarkable FSL performance (Accuracy: 98.33% ± 0.03%), remarkably outperforming both CNN models. This finding is particularly relevant for retail environments where new or seasonal products are frequently introduced and annotated data may be limited. The minimal standard deviation further demonstrates the model’s stability and suitability for low-resource classification tasks.

Zero-shot learning

In zero-shot scenarios, the FAN-based model achieved the highest top-1 (98.39%) and top-5 (99.48%) accuracies, validating its capacity to generalize across unseen product categories. This result implies that the model can be used for immediate classification of novel items without requiring retraining—an essential feature for dynamic retail settings.

Virtual shelf construction

The introduction of a multi-image virtual shelf mechanism, backed by a modified Needleman–Wunsch alignment algorithm, allows accurate reconstruction and compliance verification even under limited capture conditions. This innovation extends practical applicability to narrow aisle environments and improves audit completeness without imposing additional burdens on store employees.

The system’s high accuracy and scalability directly support operational efficiency, real-time shelf auditing, and centralized compliance monitoring across distributed retail networks. Its robustness across few-shot and zero-shot settings ensures long-term adaptability as product assortments evolve. Moreover, the modular architecture enables integration with edge computing platforms for latency reduction and future incorporation of active learning pipelines to update the model continuously.

Limitations of the study

As summarized in Sect. 1.3, this study contributes an end-to-end planogram compliance framework that integrates multi-image virtual shelf reconstruction, product detection and classification, and scalable deployment for real-world retail environments. These contributions demonstrate the feasibility and practicality of AI-driven shelf management at nationwide scale.

To improve the real-world applicability and robustness of the proposed planogram compliance system, several limitations should be acknowledged:

-

1.

Product occlusion is common in retail shelves, affecting accurate planogram compliance checks. However, this study does not provide a detailed solution for addressing scenarios where products are occluded, facing backward, or overlapping with other merchandise.

-

2.

As the primary focus of this study is on constructing virtual shelves rather than evaluating deep learning model performance, our experiments utilize only classic models such as YOLOv8, Deformable DETR, EfficientNet-B4, ResNet101, and FAN-Based Hybrid Model for comparison, rather than the most state-of-the-art model selections.

Discussion

As revealed from the experiments, both models trained from scratch on the proposed detection and classification datasets and fine-tuned achieve good results on the proposed datasets. When deployed using a specialized inference server, described in Table 9, these models can provide quick inference on the images taken by users, reducing the need for manual planogram checking. Given the future deployment to thousands of 7-Eleven stores in Taiwan, these time savings quickly add up.

While our datasets and system may still have some limitations in visual diversity, it is important to note that all data were collected on-site in three different 7-Eleven stores, at various times and from different angles, to closely reflect real operational environments. Additionally, We applied extensive data augmentation—including flips, rotations, affine and perspective transformations, color jittering, and random masking—to increase visual diversity in our product recognition dataset and improve model generalization. Our product classification model, FAN transformer, achieves very high accuracy on independently collected test sets, demonstrating sufficient reliability for the defined application scenario. Nevertheless, we recognize that incorporating even greater diversity, such as more store types or rare viewpoints, could further improve the robustness of the model, and this remains a direction for future enhancement.

Our study has effectively addressed the challenge of class imbalance, which is inherent in the product recognition dataset, by employing a weighted sampling strategy and focal loss during model training. These approaches not only ensured a more balanced representation of each class in the training batches but also enhanced the model’s ability to learn from minority classes. The consistently high precision, recall, and F1 scores observed in Table 6, indicating the success in mitigating the potential negative impacts of data imbalance. These results underscore the practical applicability and reliability of our methodology for real-world retail scenarios.

Our deployment and scalability analysis demonstrates that the proposed planogram compliance system is capable of robust and efficient operation under high load conditions, as might be encountered in real-world retail scenarios. The observed throughput trends reveal that while the system approaches saturation under heavy workloads, it maintains stable response rates without critical performance degradation. The integration of NVIDIA Tensor RT inference acceleration proved to be highly effective, improving response speed by up to 1.5× and ensuring timely processing even as request volumes increase. These findings collectively affirm the scalability and deployment readiness of our solution, making it well-suited for large-scale, high-traffic retail environments.

At present, our dataset is comprised primarily of standard shelf images, where products are correctly positioned with their front packaging facing forward. As a result, the current model has not been trained or evaluated specifically for complex scenarios such as severe occlusion, products facing backward, or overlapping merchandise. Nevertheless, the system has already been successfully deployed in real 7-Eleven stores, where it operates effectively under typical conditions and has demonstrated a clear ability to address the vast majority of practical issues encountered in daily operations. This deployment has led to substantial savings in manual inspection time for store staff. In real-world operations, the occurrence of such complex scenarios is relatively rare, and dealing with these situations does not impose a significant burden on store personnel. In cases where the system encounters shelf conditions that deviate significantly from its training data, it outputs an “Unknown” result to indicate uncertainty. To further enhance the real-world applicability and robustness of our planogram compliance system, future work will focus on:

the systematic collection and annotation of more challenging scenarios, including highly occluded, irregularly stocked, or anomalously arranged shelves. These additional data will allow for more comprehensive analysis and model adaptation, enabling the system to better manage real-world complexities commonly observed in dynamic retail environments.

-

1.

Handling occlusion: Product occlusion is common in retail shelves, affecting accurate planogram compliance checks. In the future, we will explore some methods on solving this issue such as the GOAL approach for improved detection under cluttered conditions45.

-

2.

Broaden the model comparison: The next steps could involve experimenting with a wider range of deep learning models, including recently introduced state-of-the-art architectures. This would help determine if more advanced models can further boost recognition accuracy when working with complex cases such as occlusion, overlapping, or product package facing backwards.

-

3.

Edge computing integration: Integrating edge computing by deploying models directly on devices within the retail store could significantly reduce latency and enable real-time shelf monitoring.

-

4.

Data imbalance: The product recognition dataset has somewhat of a data imbalance issue, which can be handled in some ways, such as imbalanced learning approaches that can be used during model training. In recent years, synthetic dataset generation has become a viable way of alleviating data collection overhead. Platforms such as NVIDIA Omniverse46 allow high-quality realistic 3D models to serve as dataset samples by writing simulation scripts to generate datasets.

-

5.

Parallelizing workloads: Once the shelf rows have been identified in an image, the product detection and classification can be parallelized for quick inference. How to parallelize efficiently across shelf rows in a single image and across images could further reduce inference costs.

Data availability

The source code will be made available after cleaning and organizing the training and evaluation scripts. The datasets generated and analyzed in this study can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request without disclosing sensitive company information.

References

Wei, Y., Tran, S., Xu, S., Kang, B. & Springer, M. Deep learning for retail product recognition: challenges and techniques. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020 (1), 8875910 (2020).

Mohammed, A. M. M. A visually based approach to optimizing retail facility designs and shelve layouts. Facilities 42 (1/2), 83–104 (2024).

Sigurdsson, V., Saevarsson, H. & Foxall, G. Brand placement and consumer choice: an in-store experiment. Appl. Behav. Anal. 42 (3), 741–745 (2009).

Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. Proc of European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 213–229 (2020).

Corsten, D. & Gruen, T. Desperately seeking shelf availability: an examination of the extent, the causes, and the efforts to address retail out-of‐stocks. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 31 (12), 605–617 (2003).

Saqlain, M., Rubab, S., Khan, M. M., Ali, N. & Ali, S. Hybrid approach for shelf monitoring and planogram compliance (Hyb-SMPC) in retails using deep learning and computer vision. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022(1), 4916818 (2022).

Needleman, S. B. & Wunsch, C. D. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 48 (3), 443–453 (1970).

Yücel, M. E. & Ünsalan, C. Planogram compliance control via object detection, sequence alignment, and focused iterative search. Multimed Tools Appl. 83 (8), 24815–24839 (2024).

Yücel, M. E., Topaloğlu, S. & Ünsalan, C. Embedded planogram compliance control system. J. Real-Time Image Process. 21 (4), 145 (2024).

Santra, B. & Mukherjee, D. P. A comprehensive survey on computer vision based approaches for automatic identification of products in retail store. Image Vis. Comput. 86, 45–63 (2019).

Lowe, D. G. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. Proc IEEE ICCV 1999 (2), 1150–1157 (1999).

Bay, H., Ess, A., Tuytelaars, T. & Van Gool, L. Speeded-up robust features (SURF). Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 110 (3), 346–359 (2008).

Ray, A., Kumar, N., Shaw, A. & Mukherjee, D. P. U-pc: Unsupervised planogram compliance. Proc of European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 586–600 (2018).

Thakoor, K. A. et al. Attention biased speeded up robust features (ab-surf): A neurally-inspired object recognition algorithm for a wearable aid for the visually-impaired. IEEE ICMEW 2013, 1–6 (2013).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proc IEEE CVPR 2016, 770–778 (2016).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks 25 (Advances in NIPS, 2012).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 6105–6114. (2019).

Zhong, Z., Zheng, L., Kang, G., Li, S. & Yang, Y. Random erasing data augmentation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 34 (7), 13001–13008 (2020).

Ghosh, R. Product identification in retail stores by combining faster r-cnn and recurrent neural network. Multimed Tools Appl. 83 (3), 7135–7158 (2024).

Hu, B., Zhou, N., Zhou, Q., Wang, X. & Liu, W. DiffNet: a learning to compare deep network for product recognition. IEEE Access. 8, 19336–19344 (2020).

Saran, A., Hassan, E. & Maurya, A. K. Robust visual analysis for planogram compliance problem. IEEE IAPR MVA 2015, 576–579 (2015).

Pietrini, R., Paolanti, M., Mancini, A., Frontoni, E. & Zingaretti, P. Shelf management: A deep learning-based system for shelf visual monitoring. Expert Syst. Appl. 255, 124635 (2024).

Tonioni, A. & Di Stefano, L. Product recognition in store shelves as a sub-graph isomorphism problem. Proc ICIAP 2017, 682–693 (2017).

Laitala, J. & Ruotsalainen, L. Computer vision based planogram compliance evaluation. Appl. Sci. 13 (18), 10145 (2023).

Bolles, R. C. & Fischler, M. A. A RANSAC-based approach to model fitting and its application to finding cylinders in range data. IJCAI 1981, 637–643 (1981).

Akerele, J. I., Uzoka, A., Ojukwu, P. U. & Olamijuwon, O. J. Data management solutions for real-time analytics in retail cloud environments. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 5 (11), 3180–3192 (2024).

Pearson, K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Lond. Edinb. Dubl Phil Mag. 2 (11), 559–572 (1901).

Campello, R. J., Moulavi, D. & Sander, J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. Pacific-Asia conference on knowledge discovery and data mining 160–172 (2013).

Zhu, X. et al. Deformable detr: deformable Transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2010.04159 (2020).

Varghese, R. & Sambath, M. Yolov8: A novel object detection algorithm with enhanced performance and robustness. Proc IEEE ADICS 2024, 1–6 (2024).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. Proc IEEE CVPR 2023, 7464–7475 (2023).

Wang, C. Y. et al. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. Proc IEEE CVPR 2023, 7464–7475, 390–391 (2020).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. Proc IEEE CVPR 2018, 8759–8768 (2018).

Rezatofighi, H. et al. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. Proc IEEE CVPR 2019, 658–666 (2019).

Jocher, G., Chaurasia, A. & Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8, Version 8.0. 0 (Ballenger Creek, MD, 2023). USA. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics

Lin, T. Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Proc Computer vision–ECCV 2014, 740–755 (2014).

Zhou, D. et al. Understanding the robustness in vision transformers. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. ICML 2022, 27378–27394 (2022).

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. Proc IEEE ICCV 2017, 2980–2988 (2017).

Wang, Y., Yao, Q., Kwok, J. T. & Ni, L. M. Generalizing from a few examples: A survey on few-shot learning. ACM Comput. Surveys. 53 (3), 1–34 (2020).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. Proc IEEE CVPR 2009, 248–255 (2009).

Raghu, M., Zhang, C., Kleinberg, J. & Bengio, S. Transfusion: Understanding transfer learning for medical imaging. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 32. (2019).

Li, L., Cherouat, A., Snoussi, H. & Wang, T. Grasping with Occlusion-Aware ally method in complex scenes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 22, 5944–5954 (2025).

NVIDIA. Develop and Deploy the Next Era of Physical AI Applications and Services. url: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/omniverse/ (2025).

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), ROC. Taiwan, under Grant No. NSTC 114-2622-E-992 -009.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, R.O.C. (NSTC 114-2622-E-992 -009)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y.O. is the corresponding author and responsible for ensuring that the descriptions are accurate and agreed by all authors. T.Y.O also devised the project, the main conceptual ideas and proof outline. A.P. & C.L. developed the theoretical formalism, performed the analytic calculations and performed the numerical simulations. A.W. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, TY., Ponce, A., Lee, C. et al. Real-time retail planogram compliance application using computer vision and virtual shelves. Sci Rep 15, 43898 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27773-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27773-5