Abstract

Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) is a promising solution for underwater acoustic communication (UWA); however, it requires careful handling of the challenges of large multipath and severe Doppler effects inherent in underwater acoustic communication. This paper proposes a novel feedforward backpropagated neural network (FBNN) implementation for Doppler scaling estimation using UWA cyclic-prefix (CP) OFDM communication. A two-layered input-output feedforward network is utilized with three different backpropagated training algorithm variants: Fletcher-Reeves Conjugate Gradient (CGF), Polak-Ribiére Conjugate Gradient (CGP), and Conjugate Gradient with Powell/Beale Restarts (CGB). The proposed approach calculates the Doppler scale factor by combining the neural computational power with the accuracies offered by the three training algorithms. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed FBNN implementation, root mean square error (RMSE) is used as a performance metric for different multipath and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) channel conditions. The paper also presents a comparison of the proposed FBNN-based training algorithms’ performance with that of the benchmark offered by conventional methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

UWA channel is quite a challenging communication medium for its susceptibility to environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, and pressure1. Furthermore, due to the slow propagation speed and tidal moment of acoustic waves in underwater medium, underwater wireless acoustic communication becomes even more challenging, resulting in severe multipath, delay-spread, and Doppler spread2,3. Consequently, the challenges of inter-symbol interference (ISI) and inter-carrier interference (ICI) occur. To cope with these challenges, OFDM has been widely utilized for the last few decades and is considered a promising choice for efficiently handling the frequency-selective channel and enabling high data rate communication3,4,5. Different variants have also been proposed in literature to provide better noise immunity and bit error rate performance while maintaining low implementation costs6. One such variant is CP-OFDM that has been widely studied for underwater acoustic communication. The use of cyclic prefix and orthogonal subcarriers offers various advantages, however, it also requires delicate tackling of rapid time variation that is present due to the severe Doppler effect in the case of underwater channel2,4,7. If rapid time variation is not handled carefully, the frequency shift due to the Doppler effect compromises the orthogonality between the OFDM subcarriers, leading to ICI4. The mitigation of the Doppler effect and its compensation therefore, become essential in UWA OFDM communication to fully exploit the potential of OFDM technology.

Various methods have thus been developed in the literature to estimate the Doppler effect for underwater acoustic OFDM communication systems, including Doppler-insensitive waveforms, Doppler-sensitive waveforms, the least-square methods, cross-correlation-based methods, and auto-correlation-based methods4,7,8,9,10. Among them, the classical approach is the use of a signal structure that contains a Doppler-insensitive preamble, and postamble9 like a linear frequency modulated waveform and hyperbolic frequency modulated waveform11,12. Similarly, the Doppler sensitive waveform is developed to estimate the Doppler scale factor that uses the preamble, consisting of an m-sequence-coded waveform and the Costas waveform8. Doppler sensitive waveform method uses a cross-correlator bank, where the correlator resulting in a maximum peak is selected as the true Doppler scale estimate8. One of the common disadvantages of these Doppler-insensitive and Doppler-sensitive waveform methods is the signal overhead7. Other disadvantages include a large delay time and high computational complexity7. A least-square (LS) method is also introduced to estimate the Doppler scale factor in10, however, this method requires an iterative solution and needs to be channel equalized first. Therefore, the LS method may not be a viable option in a practical UWA communication system. On the other hand, a more common method used in UWA is auto-correlation-based Doppler scale estimation. Instead of preamble and postamble, auto-correlation method uses CP on the receiver side to estimate the Doppler scale factor4,7,13,14. The accuracy of auto-correlation-based Doppler scale estimation directly depends on the sampling rate of the received signal. A higher sampling rate of the received signal provides a better estimate of a Doppler scale factor, but at the cost of computational complexity4. To resolve this issue of computational complexity, an interpolation technique is introduced4,7,15,16. To summarize, serious efforts are made to estimate and compensate the Doppler effect through conventional approaches4,7,8,9,10, with each one having its advantages and limitations.

With the rapid development and progress in the use of deep learning algorithms, and their advantages in terms of performance, recently, non-conventional deep learning methods have been introduced for UWA OFDM communication17,18,19,20. However, deep learning-based methods so far used in UWA OFDM communication are mainly related to channel estimation. For example, Liu et. al propose a deep neural network-based model: CsiPreNet, where a convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) are integrated to predict channel state information for an adaptive UWA downlink orthogonal frequency division multiple access17. Similarly, Li et. al, in another study, propose a denoising autoencoder deep neural network (DAE-DNN) to improve channel estimation of a UWA OFDM communication by suppressing the impulsive noise18. Although deep learning-based methods are applied to channel estimation, little to no work is done towards time-varying channels, including the Doppler effect, a crucial factor in UWA communication. Jia et.el19 exploits the sparse nature of the UWA communication channel and considers the time-varying channel with a uniform Doppler, however, they did not explicitly estimate the Doppler scale factor. In another work21, Hassan et.al propose a deep learning-based channel estimator in the presence of Doppler shifts, however, their study also predicts the transmitted information bits directly without explicitly estimating the Doppler scale factor. We, therefore, identify this gap and consider a time-varying UWA channel having both multipath and the Doppler effect. We further exploit the novel application of a feedforward neural network for estimating the Doppler scale factor in a time-varying UWA CP-OFDM communication channel.

Feedforward neural networks have been widely used in several real-world applications such as the healthcare sector22,23,24, structural health monitoring25,26, mechanics27, environmental monitoring28, and wireless communication29,30. Driven by these diverse applications of feedforward neural networks, we in this work plan to investigate its performance in estimating the Doppler scale factor in UWA CP-OFDM communication. Toward this end, we use an FFBN with three different training algorithms. The main contributions in the paper are summarized below:

-

In this paper, we introduce the novel application of a feedforward backpropagation neural network for estimating the Doppler scale factor in UWA CP-OFDM communication. Unlike the conventional method, where two CP-OFDM symbols are used to improve the Doppler scale factor estimation accuracy, we use a single OFDM symbol approach, achieving spectral efficiency.

-

In FBNN, we utilize three different training algorithms, namely FBNN-based Fletcher-Reeves Conjugate Gradient (FBNN-CGF), FBNN-based Polak-Ribi’ere Conjugate Gradient (FBNN-CGP), and FBNN-based Conjugate Gradient with Powell/Beale Restarts (FBNN-CGB).

-

The performance comparison of the three FBNN-based training algorithms is carried out in terms of mean square error (MSE) and error histograms under dynamic channel conditions of varying SNR and number of paths.

-

A synthetic dataset is generated with all real-time and key parameters such as multipath, uniformly distributed Doppler scale factor, and signal-to-noise ratio.

-

The performance analysis of the FBNN-CGF, FBNN-CGP, and FBNN-CGB is carried out through the performance metric of RMSE of Doppler speed in m/s by estimating the difference between the true and estimated Doppler scale factor. In addition, a comparison has been made with the conventional signal processing method, such as pilot-assisted autocorrelation and pilot-assisted cross-correlation-based Doppler scale estimation. Additionally, the results are further verified using a watermark NOF1 channel dataset.

-

Finally, we calculate the bit error rate (BER) performance of the relatively best FBNN-based training algorithm achieved from the RMSE performance comparison.

UWA CP-OFDM system model

Since CP-OFDM is most commonly used in underwater acoustic communication, we therefore start with the CP-OFDM communication system model that includes time-varying information of underwater channel. Consider a CP-OFDM communication system4,7, that has a total number of subcarrier K, s[k] is the baseband modulated (phase shift keying (PSK) or quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM)) symbol on the kth subcarrier, the transmit CP-OFDM passband signal in continuous time domain \(\tilde{x}(t)\) can be written as

where \(f_{k}=f_{c}+\frac{k}{T}\) denotes the frequency of the kth subcarrier, here \(f_{c}\) is the carrier frequency, T represents OFDM symbol duration, and the rectangular pulse shaping window is denoted by q(t). The rectangular pulse shaping window q(t) can be written in two different signal formats based on a single OFDM symbol, that is, T or two identical OFDM symbols, that is, 2T as depicted in Fig. 14. Let’s denote the duration of CP with \(T_\textrm{cp}\), the q(t) can be written as

CP-OFDM signal structures (a) Single CP-OFDM symbol and (b) Two CP-OFDM symbols, where CP represents cyclic prefix, and X is the OFDM symbol7.

We use (3) instead of (2) in our proposed FBNN-based Doppler scale estimation as it uses single OFDM symbols4 to help in efficiently utilizing the scarce underwater spectrum. Next, the channel impulse response with L number of paths can be expressed as

where \(A_l\), \(\tau _{l}\), and \(a_{true}\) denote the amplitude, time delay of the lth path, and true Doppler scale factor, respectively. After passing the passband CP-OFDM signal through a multipath channel, the received passband signal can be written as

where \(\tilde{n}(t)\) denotes the noise. The modified received passband signal after insertion of (1) in (5) can be expressed as4,7

Next, the received passband signal is downshifted and passed through a low-pass filter. The final received baseband signal y(t) can then be written as4,7

where \(A_{l}^{c} = A_l e^{-j2\pi f_{c}\tau _{l}}\) denotes the baseband equivalent complex path amplitude, while z(t) is the baseband noise. With an assumption that the signal sampling frequency is \(f_s = \lambda B = \frac{\lambda K}{T}\), where B and \(\lambda\) denote the OFDM signal bandwidth and oversampling factor. When \(n \in \left[ -\frac{T_\textrm{cp}-\tau _\textrm{max}}{1+a_{true}}f_s, \frac{2T-\tau _\textrm{max}}{1+a_{true}}f_s\right]\), where \(\tau _\textrm{max}\) is the maximum delay spread, then from (7), the sampled digital signal from can be expressed as:

where \(\epsilon _{a_{true} }=f_{c} a_{true} T\) denotes the normalized Doppler shift, and here \(f_c\) is the carrier frequency.

Proposed FBNN-based Doppler scale estimation approach

The Doppler scaling factors estimation for underwater acoustic communication requires dealing with complex data, and therefore the paper proposed employs a feedforward neural network with back-propagated training algorithm. Both the neural network and training algorithms are further explained in the following subsections:

Feedforward Backpropagation Neural Network (FBNN)

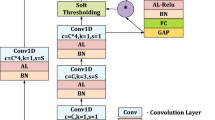

Figure 2 shows a block diagram of an OFDM receiver with Doppler scale estimation. The Doppler Estimation block utilizes FBNN to estimate Doppler scaling factors. The input of this block is y[n] (eq 8) where \(a_{true}\) is the target Doppler scaling factor needs to be estimated. FBNN takes y[n] as input, and \(a_{true}\) as target during the training phase. The FBNN consists of an input layer and one or more hidden layers to estimate the Doppler scale factor (\(a_{est}\)) in its output layer. A typical workflow at the level of neurons in different layers in an FBNN is listed below.

-

Each hidden layer neuron receives an input that is a weighted combination of the input from the prior layer, which is then passed through a nonlinear activation function. Therefore, weighted output \(z_j[k]\) of the j-th neuron in the hidden layer is specified using a nonlinear activation function g and utilizing the weight \(c_{ji}\) from input neuron i to hidden neuron j as

$$\begin{aligned} z_j[k]=g\left( \sum _{i=1}^n c_{ji}\cdot y_i[k]+b_j\right) , \end{aligned}$$(9)where \(b_j\) is the bias of the hidden neuron j and n represents the number of input samples.

-

The output neuron r yields a value \(a_{est}^r[k]\) by using a nonlinear activation function h and utilizing the weight \(v_{rj}\) from hidden neuron j to output neuron r as

$$\begin{aligned} a_{est}^r[k]=h\left( \sum _{j=1}^m v_{rj}\cdot z_j[k]+b_r\right) , \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(b_r\) is the bias of the output neuron r and m represents the number of hidden neurons.

The weight factor between two neurons in the adjacent layers is updated during the training phase. Next, details of the training algorithms are presented along with its different variants.

Conjugate gradient-based training algorithms

During the training phase, an FBNN uses various numerical optimization methods to optimize a cost function that measures the error between the estimated values (\(a_{est}\)) and the actual target values (\(a_{true}\)). The most preferred optimization methods are conjugate gradient (CG) algorithms due to their precision, robustness, and faster convergence31. Multiple variants of the CG algorithm include the Fletcher-Reeves conjugate gradient, the Polak-Ribiére conjugate gradient, and the conjugate gradient with Powell/Beale restarts.

A CG-based algorithm is an iterative method. Like a general numerical optimization method, it begins by defining an objective function for a minimization problem as follows:

where \(\textbf{a}\) is a vector of Doppler scales, and \(\textbf{A}\) is a Hessian matrix with elements \(\textbf{A}_{(i,j)}\)

and \(\textbf{u}=[u_1,u_2,\cdots ,u_N]^T\) with i-th value \(u_i\) denoted as

represents the error between the i-th values \(a_{true}^i\) and \(a_{est}^i\) of the true and estimated Doppler scales, respectively.

Let \(\textbf{u}^k\) denote the current estimate of the weights; then, the solution algorithm seeks an update, \(\textbf{u}^{k+1}\), which results in: \(f(\textbf{a},\textbf{u}^{k+1})<f(\textbf{a},\textbf{u}^{k})\), termed the descent condition. Consequently, \(\textbf{u}\) is updated as per the following rule:

where \(\textbf{d}^{k}\) represents a search direction and \(\alpha _k\) is the step size that gets updated by minimizing \(f(\textbf{a},\textbf{u})\) along \(\textbf{d}^{k}\).

The iteration in (14) can be solved in two steps as listed below.

-

1.

Finding the suitable search direction \(\textbf{d}^{k}\) along which the value of the function locally decreases.

-

2.

Performing a line search along \(\textbf{d}^{k}\) to find \(\textbf{u}^{k+1}\) such that \(f(\textbf{u}^{k+1})\) reaches its minimum value.

In the context of the CG algorithm, let \(\mathbf {d^0,d^1,d^2,\cdots ,d^{n-1}}\), where \(\textbf{d}^i \textbf{A d}^j=0, i\ne j\) denote conjugate directions with respect to the Hessian matrix \(\textbf{A}\). This ensures that the search directions are orthogonal with respect to the matrix \(\textbf{A}\), leading to an efficient descent in the solution space. Starting from \(\mathbf {d^0}\), taken to be the steepest descent direction, we can use the following procedure to generate initial and next directions denoted \(\textbf{d}^0\) and \(\textbf{d}^{k+1}\), respectively as

where \(\textbf{d}^0\) is chosen arbitrarily and \(\nabla f(\cdot )\) denotes the gradient.

Multiplying both sides in (16) by \(\textbf{d}^k \textbf{A}\) and equating to zero gives \(\beta _k\) as

where \((\cdot )^T\) denotes the matrix transpose. Having found \(\beta _k\) leads to finding \(\textbf{d}^{k+1}\) that can be utilized in (14) to finally compute \(\textbf{u}^{k+1}\).

Figure 3 shows the learning process of the CG algorithm (as formulated in (11) to (17)) in the form of a flowchart. The expression in (17) can be further simplified if additional assumptions about the function and the line search algorithm are made, leading to different versions of the CG methods, such as CGF, CGP, and CGB, as described in the following subsections.

Fletcher-Reeves Conjugate Gradient (CGF)

For the Fletcher-Reeve update, \(\beta _k\) is calculated using the procedure listed below.

Because

where for quadratic functions

therefore by exact line search condition

results in \(\beta _k\) as the ratio of the squared-norm of the current gradient to the squared-norm of the previous gradient using the following relation

Polak-Ribiére Conjugate Gradient (CGP)

For the Polak-Ribiére update, the constant \(\beta _k\) is calculated as the inner product of the previous change in the gradient with the current gradient divided by the squared norm of the previous gradient. Firstly, in the case of exact line search, we notice that

Thus,

Typically, the CGP algorithm performs similarly to the CGF algorithm. For a given Doppler scale estimation problem, it may not be possible to predict which algorithm will perform best, however, the storage requirements for the CGP algorithm are slightly larger than those for the CGF algorithm.

Conjugate Gradient with Powell/Beale Restarts (CGB)

To improve the efficiency during the search for optimal direction, the Powell-Beale technique verifies if there is any orthogonality between the current gradient \(\nabla f(\textbf{u}^{k+1})\) and the previous gradient \(\nabla f(\textbf{u}^{k})\) using an inequality

The search direction is reset to the negative of the gradient if this condition is satisfied. In some implementations, \(\beta _k\) might be calculated as

For some problems, the CGB algorithm usually performs slightly better than the CGF and CGP algorithms. In the next section, we evaluate the performance of the three training algorithms. However, the storage requirements for the CGB algorithm are slightly higher than those for the CGP algorithm.

Computational complexity of training algorithms

The three conjugate gradient methods, that is, CGF, CGP, and CGB, that have been presented as candidate training algorithms in the preceding subsections, have multiple key factors that influence their complexity. These include problem scale, computational complexity, and memory requirements. Table 1 shows a comparison of the CGF, CGP, and CGB algorithms. As can be seen, all three algorithms exhibit the same computational complexity for a given number of variables N. However, the CGF algorithm is the best in terms of memory requirement compared to CGP and CGB. However, for a specific implementation on the edge, using techniques like pruning and quantization may further reduce the size and complexity of the model while retaining performance. This will further reduce the memory requirements on the edge.

FBNN implementation and performance evaluation

Figure 4 shows FBNN implementation block diagram for Doppler scaling estimation. A healthy dataset (for CP-OFDM) is generated of 1900 complex random vectors with each vector consisting of 12992 values. The dataset contains 19 different SNR values between \(-10\) dB to 26 dB with an index range per SNR of 100. With this formulation, three different datasets are created with number of paths as: 1, 5, and 10. For channel settings, the time interval between two paths having a mean value of 1ms is exponentially distributed, while paths amplitudes are Rayleigh distributed. The average power of each path is exponentially decayed by 20dB in a delay spread of 30ms, and the true Doppler scale factor (\(a_{true}\)) is uniformly distributed. Table 2 summarizes the various parameter values that generate these datasets.

For each dataset, about \(70\%\) of complex vectors y[n] (with combined real and imaginary parts) act as input during the training phase. Similarly, each input vector corresponds to a precomputed Doppler scale factor \(a_{true}\) as the target. Furthermore, we use linear regression to train the FBNN network. A FBNN simulation requires a) data distribution between training, testing, and validation phases, b) a training algorithm, and c) specifying the activation functions for hidden and output layers. Since the FBNN neural network architecture is not very deep, a two-layer neural network: a single hidden layer with a size of 3 neurons and an output layer is sufficient in our case. Table 3 lists the parameters and settings used to train, test, and validate the FBNN for the estimation of the Doppler scale.

A detailed stepwise implementation of FBNN is listed below:

-

During the training phase, \(70\%\) samples are randomly selected for both input and target. The remaining \(30\%\) samples (of both input and output) are reserved for the validation and testing phase.

-

Three training algorithms (CGF, CGP, and CGB) are chosen to train our FBNN network.

-

The activation functions used in the hidden and output layers are tansig and purelin.

-

The FBNN is then tested and validated using statistical measures such as mean squared error (MSE) and error histograms.

-

Finally, Doppler scale factors are estimated using the designed FBNN network.

Performance evaluation

We evaluate the performance of the three FBNN-based training algorithms: CGF, CGP, and CGB, by examining both the performance plot and error histogram. Moreover, root mean square error vs. signal-to-noise ratio plots are also used as a performance metric for Doppler scale factor estimation evaluation for each case of multipath. The RMSE of a Doppler speed in m/s can be expressed as

where \(c=1500\) m/s is the underwater sound speed.

Training, testing and validation results

This subsection presents the performance analysis of the FBNN-CGF, FBNN-CGP, and FBNN-CGB in terms of performance plots of mean square error (MSE) and error histograms as depicted in Figs. 5, 6, and 7.

Figure 5 shows MSE and error histogram plots for the FBNN-CGF algorithm with channel paths as 1, 5, and 10. From Fig. 5a, b, and c, the performance of the FBNN-CGF algorithm against training, testing, and validation data can be seen in terms of MSE vs epochs. It may be noted that MSE is lower for a single channel path and becomes larger when channel paths are increased to 10. The error histogram plots shown in Fig. 5d, e, and f are also consistent with the MSE plots results, where the error is lower in the case of a single channel path and becomes significant when 10 multipath are used.

Figure 6 shows MSE and error histogram plots for the FBNN-CGP algorithm with channel paths of 1, 5, and 10. The result trends shown in Fig. 6 are similar to those shown in Fig. 5 in terms of both MSE and error histograms. However, it can be observed that FBNN-CGP performs relatively poorly compared to FBNN-CGF.

Figure 7 shows MSE and error histogram plots for the FBNN-CGB algorithm under channel paths as 1, 5, and 10. A similar conclusion of results with consistent trends in MSE and error histogram plots with Figs. 5 and 6 may be seen. The performance of FBNN-CGB outperforms when the channel path is set to 1 as compared to channel paths set to 5 and 10. In addition, it may also be observed that FBNN-CGB performance is relatively better than FBNN-based CGF and CGP training algorithms.

RMSE vs. SNR comparisons

The performance of various FBNN-based training algorithms for estimating the Doppler scale factor is carried out by calculating RMSE vs. SNR plots as depicted in Figs. 8, 9, and 10.

Figure 8 shows RMSE of Doppler speed in m/s vs. SNR in dB’s for a single channel path. In this Figure, the proposed FBNN-based Doppler scale estimation algorithms are further compared with conventional auto-correlation and cross-correlation-based Doppler scale estimation methods. The parameters used to calculate the RMSE of the conventional methods are kept the same as given in Table 2 to ensure a fair comparison. It can be observed from the Fig. 8 that our proposed Doppler scale estimation algorithms not only estimate the Doppler scale factor but also show significant performance, especially in the lower SNR regions, where the conventional methods: autocorrelation-based methods and pilot-based cross-correlation method performance is very poor. The autocorrelation-based method (denoted by AC-M1) performs better in higher SNR regions as compared to other conventional and non-conventional FBNN-based algorithms.

Considering the FBNN-based Doppler scale factor estimation, FBNN-CGB outperforms FBNN-CGF and FBNN-CGP. This behavior is consistent with the fact described in Sect. "Conjugate Gradient with Powell/Beale Restarts (CGB)".

Figure 9 shows RMSE of Doppler speed in m/s vs. SNR in dB’s for 5 channel paths. Similar to Fig. 8 results analysis, the trend of RMSE vs. SNR of each algorithm for both conventional and non-conventional methods is the same. However, it can be observed that RMSE is significantly larger in this case, which is mainly due to the multipaths. Furthermore, in this case, FBNN-based CGB, CGF, and CGP algorithms perform almost similarly. Similarly, the non-conventional FBNN-based algorithms outperform in lower SNR as compared to conventional-based AC and CC methods.

Figure 10 shows RMSE of Doppler speed in m/s vs. SNR in dB’s for 10 channel paths. The results trend is quite similar to Fig. 9. Non-conventional FBNN-based algorithms perform better in lower SNR, with FBNN-CGB performing a bit better than FBNN-CGF and FBNN-CGP. While, the autocorrelation-based method 1 performs better in high SNR regions.

To conclude, the results presented in Figs. 8, 9, and 10, show that non-conventional FBNN-based algorithms perform better in the lower SNR region as compared to conventional auto-correlation and cross-correlation based methods. Among FBNN-based algorithms, CGB-based training algorithm performs relatively better as compared to FBNN-based CGF and CGP algorithms. Among the conventional methods, Auto-correlation based method 1 (AC-M1) performs better in high SNR regions.

BER vs. SNR analysis

Since, FBNN-CGB algorithm performs relatively better than FBNN-based CGF and CGP algorithms, therefore, we further carried out bit error rate vs SNR simulations for the CGB training algorithm only for different multipath channel settings. In Fig.11, the bit error rate vs. signal-to-noise ratio is shown for the FBNN-CGB algorithm for different numbers of paths. It can be seen from Fig. 11 that when a single channel path is used, the BER performance is better as compared to channel multipath scenarios. At SNR of 4 dB, the bits are successfully decoded and BER becomes 0. However, the BER performance is lower when channel paths are 5 and 10.

Experimental evaluation through watermark channel

In this section, we perform further evaluation of the FBNN-based Doppler scale estimation through the Watermark channel dataset32. To be specific, we used Norway-Oslofjord (NOF1) data, which is a single-input-single-output (SISO) shallow water setup, where transmitter and receiver are both bottom-mounted. The NoF1 data is actually the time varying impulse response (TVIR) measurements, containing a total of 60 channels; because of repeating the experiments 60 times at an interval of 400 seconds, where one TVIR measurement lasts over 32.9 seconds, therefore, a total of 33 minutes of play time32. Table 4 summarizes the NOF1 channel and measurement condition parameters. The OFDM parameters used are listed in Table 5.

The dataset is generated using a single NOF1 channel (channel 59 of the NOF1) and introducing a uniformly-distributed Doppler scale factors to the transmitted OFDM signal; therefore, it can be termed as a semi-realistic dataset. With the use of the SNR loop as mentioned in Table 5, which is further iterated 10 times for each SNR, a healthy dataset is generated. In our case, the packets per soundings of the transmitted OFDM signal are 155; therefore, the dimension of the transmitted OFDM signal becomes \(1550 \times 9216\) per SNR. To evaluate the FBNN-based CGP, CGF, and CGB algorithms, we divide the dataset into 70%, 15%, and 15% for training, validation, and testing. The hidden layer size used in FBNN-based CGP, CGF, and CGB models is 20. First, we evaluate the performance of the proposed FBNN-based training algorithms through performance plots and error histograms, and then calculate the RMSE of each method.

Performance analysis of FBNN-based algorithms using watermark NOF1 channel where (a) and (b) show performance plot and error histogram for FBNN-CGP, (c) and (d) show performance plot and error histogram for FBNN-CGF, CGF, and (e) and (f) show performance plot and error histogram for FBNN-CGB algorithm.

Figure 12 shows the performance of the FBNN-based CGP, CGF, and CGB algorithms for Doppler scale estimation in UWA OFDM communication using the NOF1 channel. It can be observed from the Fig. 12 that the performance of the FBNN-based CGP algorithm is lower, while FBNN-based CGB algorithm outperforms using the watermark NOf1 channel. These results show a similar trend and conclusion drawn using the synthetic UWA channel dataset. Additionally, Fig. 13 shows the RMSE versus SNR results for all three FBNN-based CGP, CGF, and CGB algorithms. It can be seen that FBNN-CGB performance is better compared to CGF and CGP algorithms, which is again a similar conclusion to the results achieved from using the synthetic UWA channel dataset.

Conclusion

Doppler estimation has always been a challenging task in underwater acoustic communication. This paper applies a feedforward backpropagated neural network (deep learning-based) approach to estimate Doppler scale factors for underwater acoustic CP-OFDM communication. Furthermore, different conjugate gradient training algorithms: CGF, CGP, and CGB, are applied and compared to evaluate the performance and accuracy. From the results, it can be concluded that overall, FBNN-based training algorithms perform better in lower SNR regions for single and multipath channel settings. Furthermore, FBNN-CGB outperforms CGP and CGF training algorithms. The performance of the FBNN-based algorithms is further verified using the UWA watermark channel, which draws a similar conclusion.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jiang, R., Wang, X., Cao, S., Zhao, J. & Li, X. Deep neural networks for channel estimation in underwater acoustic OFDM systems. IEEE access 7, 23579–23594 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Li, J., Zakharov, Y., Li, X. & Li, J. Deep learning based underwater acoustic OFDM communications. Appl. Acoust. 154, 53–58 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Chang, J., Liu, Y., Xing, L. & Shen, X. Deep learning and expert knowledge based underwater acoustic OFDM receiver. Phys. Commun. 58, 102041 (2023).

Wan, L. et al. Fine doppler scale estimations for an underwater acoustic CP-OFDM system. Signal Process. 170, 107439 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Tai, Y., Li, C. & Meriaudeau, F. A machine learning label-free method for underwater acoustic OFDM channel estimations. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Underwater Networks & Systems, 1–5 (2021).

Kumar, P. & Kumar, P. DCT based OFDM for underwater acoustic communication. In 2012 1st International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology (RAIT), 170–176, https://doi.org/10.1109/RAIT.2012.6194500 (2012).

Muzzammil, M., Jia, H., Wan, L. & Qiao, G. Further interpolation methods for doppler scale estimation in underwater acoustic CP-OFDM systems. In 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP), 295–300 (IEEE, 2019).

Jin, Q., Wong, K. M. & Luo, Z.-Q. The estimation of time delay and doppler stretch of wideband signals. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 43, 904–916 (1995).

Li, B., Zhou, S., Stojanovic, M., Freitag, L. & Willett, P. Multicarrier communication over underwater acoustic channels with nonuniform doppler shifts. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 33, 198–209 (2008).

Pan, W., Liu, P., Chen, F., Ji, F. & Feng, J. Doppler-shift estimation of flat underwater channel using data-aided least-square approach. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. 7, 426–434 (2015).

Kramer, S. A. Doppler and acceleration tolerances of high-gain, wideband linear FM correlation sonars. Proc. IEEE 55, 627–636 (1967).

Kroszczynski, J. J. Pulse compression by means of linear-period modulation. Proc. IEEE 57, 1260–1266 (1969).

Ma, L., Qiao, G. & Liu, S. A combined doppler scale estimation scheme for underwater acoustic OFDM system. J. Comput. Acoust. 23, 1540004 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Doppler estimation based on linear interpolation for underwater acoustic communication. Transactions on Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 33, e4519 (2022).

Mason, S. F., Berger, C. R., Zhou, S. & Willett, P. Detection, synchronization, and doppler scale estimation with multicarrier waveforms in underwater acoustic communication. IEEE J. on selected areas in communications 26, 1638–1649 (2008).

Chen, Z., Zheng, Y. R., Wang, J. & Song, J. Synchronization and doppler scale estimation with dual PN padding TDS-OFDM for underwater acoustic communication. In 2013 OCEANS-San Diego, 1–4 (IEEE, 2013).

Liu, L., Cai, L., Ma, L. & Qiao, G. Channel state information prediction for adaptive underwater acoustic downlink OFDMA system: Deep neural networks based approach. IEEE Transactions on Veh. Technol. 70, 9063–9076 (2021).

Li, X., Han, Z., Yu, H., Yan, L. & Han, S. Deep learning for OFDM channel estimation in impulsive noise environments. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 125, 2947–2964 (2022).

Jia, S., Zou, S., Zhang, X., Tian, D. & Da, L. Multi-block sparse bayesian learning channel estimation for OFDM underwater acoustic communication based on fractional fourier transform. Appl. Acoust. 192, 108721 (2022).

Hassan, S., Chen, P., Rong, Y. & Chan, K. Y. Underwater acoustic OFDM receiver using a regression-based deep neural network. In OCEANS 2022, Hampton Roads, 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Sabna, H., Chen, P., Rong, Y. & Chan, K. Y. Doppler shift compensation using an LSTM-based deep neural network in underwater acoustic communication systems. In OCEANS 2023-Limerick, 1–7 (IEEE, 2023).

Chen, Y., Zhang, C., Liu, C., Wang, Y. & Wan, X. Atrial fibrillation detection using a feedforward neural network. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 42, 63–73 (2022).

Willsey, M. S. et al. Real-time brain-machine interface in non-human primates achieves high-velocity prosthetic finger movements using a shallow feedforward neural network decoder. Nat. Commun. 13, 6899 (2022).

Avinash, S., Naveen Kumar, H., Guru Prasad, M., Mohan Naik, R. & Parveen, G. Early detection of malignant tumor in lungs using feed-forward neural network and k-nearest neighbor classifier. SN Comput. Sci. 4, 195 (2023).

Ho, L. V. et al. A hybrid computational intelligence approach for structural damage detection using marine predator algorithm and feedforward neural networks. Comput. & Struct. 252, 106568 (2021).

Li, H., Wang, T. & Wu, G. Dynamic response prediction of vehicle-bridge interaction system using feedforward neural network and deep long short-term memory network. In Structures, vol. 34, 2415–2431 (Elsevier, 2021).

Aldakheel, F., Satari, R. & Wriggers, P. Feed-forward neural networks for failure mechanics problems. Appl. Sci. 11, 6483 (2021).

Caraka, R. E. et al. Hybrid vector autoregression feedforward neural network with genetic algorithm model for forecasting space-time pollution data. Indonesian J. Sci. Technol. 6, 243–266 (2021).

Mehr, P. T., Koufos, K., Haloui, K. E. & Dianati, M. Low-complexity channel estimation for V2X systems using feed-forward neural networks. IET Commun. 18, 789–798 (2024).

Xu, M., Zhang, S., Ma, J. & Dobre, O. A. Deep learning-based time-varying channel estimation for RIS assisted communication. IEEE Commun. Lett. 26, 94–98 (2021).

Farizawani, A., Puteh, M., Marina, Y. & Rivaie, A. A review of artificial neural network learning rule based on multiple variant of conjugate gradient approaches. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 1529, 022040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1529/2/022040 (2020).

van Walree, P. A., Socheleau, F.-X., Otnes, R. & Jenserud, T. The watermark benchmark for underwater acoustic modulation schemes. IEEE journal of oceanic engineering 42, 1007–1018 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Ma Lu of the College of Underwater Acoustic Engineering, Harbin Engineering University, for providing valuable suggestions in this work. The authors extend their appreciation to Umm A-Qura University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4290339GSSR08.

Funding

This research work was funded by Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia under grant number: 25UQU4290339GSSR08.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. S.S., and G.Q.; methodology, M.M, S.S., and N.A.; software, M.M. and S.S; validation, M.M., S.S., and N.A.; formal analysis, S.S., N.A., G.Q., and A.A.; resources, G.Q., A.A.; data curation, M.M., S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., S.S.; writing—review and editing, M.M., N.A., G.Q., A.A; supervision, N.A., G.Q., A.A.; project administration, M.M., G.Q., A.A.; funding acquisition, G.Q., A.A. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muzzammil, M., Saleem, S., Ahmed, N. et al. Employing feedforward backpropagated neural network for Doppler scale estimation in underwater acoustic CP-OFDM communication. Sci Rep 15, 43734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27808-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27808-x