Abstract

This study proposes a DLF Multi-Scale Network Model to analyze personality traits by integrating visual and audio features from video data. Existing methods often overlook the stability and correlation of multimodal features during extraction and fusion, limiting model generalization and recognition accuracy. To address this, we propose the DWTC module, which applies Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) to decompose video frames into multi-scale representations. These representations capture hierarchical visual information (e.g., facial expressions, body movements) at varying levels of detail. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is used to extract deeper semantic features from the decomposed representations, ensuring stability and discriminability of visual features. For audio, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) is used for processing, followed by latent feature sequence alignment (LMSA) and integration to address spatio-temporal inconsistencies. This alignment enhances feature complementarity and inter-modal correlations, with final fusion at the decision level. Experiments on the First Impression V1 dataset demonstrate the superior performance of the DLF model in recognizing Big Five personality traits, achieving an average multimodal fusion accuracy of 0.9177, significantly outperforming existing models. This research provides insights into mapping behavioral characteristics to personality traits in digital environments and holds practical value for mental health assessment and personalized recommendation systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amid the wave of digital transformation, short-video platforms have emerged as globally influential social media paradigms. As reported in recent studies, global leading short-video platforms have reached a milestone of monthly active users (MAUs) exceeding 3 billion, with daily average usage duration surpassing 95 min, generating vast multidimensional behavioral datasets. This evolving media ecosystem not only redefines interpersonal interaction mechanisms but also provides revolutionary data sources for psychological research. Crucially, user-generated spontaneous behavioral data exhibit higher ecological validity compared to traditional psychometric scales, as they reflect naturalistic human behaviors in authentic digital contexts.

Personality traits, as core dimensions of individual.

differences, have traditionally been assessed through subjective self-reports and static measurement tools, which are constrained by inherent response biases (e.g., social desirability bias) and contextual specificity limitations. While classical psychometric scales grounded in the Big Five Model(Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) demonstrate robust reliability and validity, they struggle to capture dynamic behavioral manifestations across real-world scenarios.

Recent breakthrough advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, however, offer novel solutions to this impasse. Deep learning models enable automated feature extraction from unstructured video data, capturing subtle behavioral cues—such as micro-expressions, paralinguistic features(e.g., prosody, speech pauses), and gaze dynamics—that are challenging to quantify via conventional methods. Critically, the maturation of multimodal fusion techniques facilitates synchronous analysis of visual, auditory, and linguistic features, significantly enhancing the accuracy of personality trait prediction. By integrating temporally aligned multimodal representations, these approaches mitigate the limitations of unimodal analyses and provide a holistic understanding of personality expression in naturalistic settings.

This research holds dual theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, it advances the understanding of personality expression mechanisms in digital environments by constructing a "behavioral feature-personality trait” mapping model. This framework extends the theoretical implications of the primacy effect to virtual social interactions, elucidating how first impressions formed through digital behaviors (e.g., spontaneous video content) influence subsequent trait attribution. Practically, the developed personality recognition system demonstrates substantial potential for applications in mental health assessment (e.g., early-stage depression screening) and personalized recommendation system optimization. Notably, the rapid evolution of digital therapeutics (DTx) has introduced novel paradigms for mental health services. Integrating personality trait analysis derived from short-video behavioral data could enhance the diagnostic accuracy of remote psychological evaluations, particularly in resource-constrained or stigma-laden contexts. Furthermore, coupling personality-aware algorithms with recommendation engines may foster user-centric content delivery, thereby improving engagement and therapeutic outcomes.

Related work

Analysis of traditional personality trait recognition research

The study of personality traits has a long history, and psychologists have endeavored to construct systematic and integrated personality theories. Allport1 first proposed the concept of personality traits in 1921, conceptualizing them as psychological structures and neuropsychic characteristics that influence individual behavior, and classified traits into common traits and individual traits. Cattell2 published the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF) in 1949, proposing 16 personality factors. Eysenck3 identified three dimensions of personality traits through factor analysis in 1953: extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism, subsequently developing a hierarchical four-level personality structure. From the late 1960 s to the early 1970 s, Costa and McCrae4 advanced the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality—comprising neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness—based on Cattell’s framework and their empirical investigations. This model has become a pivotal framework for characterizing fundamental human traits, extensively utilized in psychological research and practice to systematically understand and address individual differences.

Research progress on deep learning-based personality trait recognition

The interdisciplinary integration of computer science and psychology initially emerged through audio-based personality trait recognition research.

Polzehl et al.5 developed a personality assessment paradigm using speech as input, where professional speakers employed distinct personality traits in vocal delivery, and encoded these vocal impressions into Big Five (NEO-FFI) traits. The results obtained by human raters show a high degree of consistency with those derived from automated reasoning methods. However, this approach overly relies on the constraint of “professionally recorded speech,” neglecting the randomness inherent in natural speech within everyday short videos. Celli et al.6 proposed an unsupervised personality recognition system that leverages linguistic features to address how different personalities interact on Twitter. However, this system relies solely on static text, handcrafted features, and a single modality.

Mohammad et al.7proposed a prosody-based automatic personality perception (APP) method that maps prosodic features to listener-attributed personality traits. The experimental results indicate that extraversion and conscientiousness show relatively high predictive accuracy, which is consistent with observations in personality psychology. However, the study focused solely on these two traits, leaving insufficient coverage of neuroticism, agreeableness, and other traits that rely more heavily on subtle prosodic variations. Su etal8. proposed a personality analysis method utilizing wavelet transforms and CNNs to extract personality traits from speech signals, in which wavelet decomposition dissected the speech signal into multi-resolution components, followed by personality trait classification through convolutional neural networks.

Recent advances in image-based feature extraction for personality trait recognition have substantially advanced the interdisciplinary convergence of computer technology and psychology, unveiling novel possibilities for synergistic development between these disciplines. Gürpnar et al.9 implemented a comprehensive analysis of facial expressions and contextual information in video sequences, employing a pre-trained VGG-19 model for deep feature extraction through three principal stages: facial alignment, feature extraction, and modeling. The kernel extreme learning machine (KELM) algorithm was utilized for personality trait modeling by integrating facial and environmental features, leveraging its computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. This process is treated as a regression problem to calculate personality trait scores. However, the fully connected layers of VGG19 are prone to losing local details of micro-expressions (such as frowns), and the kernel ELM algorithm has limited fitting capability for high-dimensional features. Beyan et al.10 developed a non-verbal feature extraction method based on deep visual activities (VA) to classify perceived personality traits from key dynamic images. Their architecture combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to model long-term visual activities and detect spatiotemporal saliency for identifying critical dynamic frames. The extracted visual activity features are encoded via covariance and utilized for personality trait recognition and classification. However, the keyframe selection relies solely on the single metric of “pixel variation intensity,” which risks misidentifying personality-irrelevant scene changes (e.g., background switching) as keyframes, leading to feature redundancy. Biel et al.11 conducted automated personality perception analysis by performing frame-by-frame examination of video image sequences with an SVM classifier, with their empirical results indicating extraversion as the most salient trait identifiable through visual cues. However, the linear classification capability of SVM struggles to handle the complex nonlinear features present in video frames. Dhall et al.12 manually extracted multi-level features such as gradient histograms from user photographs, processed facial action units and attributes using kernel partial least squares regression, performed regression analysis on these features, and subsequently implemented a CNN model for personality trait recognition. However, manual feature engineering relies heavily on researchers’ expertise and fails to integrate the automatic feature extraction capabilities of deep learning, resulting in low feature update efficiency and the need to redesign feature dimensions when adapting to new datasets.

Most personality computing studies have employed single-modality data, such as audio or visual inputs. In 2016, ChaLearn organized a challenge competition focused on automated analysis and recognition of individual personality traits from video data, with particular emphasis on first-impression formation. The competition dataset comprised meticulously curated YouTube video clips capturing human behavioral patterns and expressions across diverse situational contexts, providing robust material for training and validating participant-developed algorithmic models. A multimodal personality trait recognition methodology leveraging both video and audio data was subsequently proposed. Gülütürk13 proposed a deep residual network with dual-branch architecture (auditory and visual streams), each containing 17 layers, and fused multimodal features via a fully connected layer. However, the 17-layer branch structure leads to parameter redundancy, and the fully connected layer merely performs feature concatenation, failing to account for the temporal synchronization between audio prosody and visual actions. Zhang14 proposed the DBR framework to capture rich information from visual and auditory modalities in videos. DBR treats videos as containing two natural modalities: visual (images) and auditory (speech). For visual modality processing, the framework modifies conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to leverage critical visual cues. The auditory modality involves extracting audio representations and constructing a linear regressor. However, the linear regressor struggles to fit the nonlinear characteristics of audio, and the visual CNN lacks optimization for inter-frame relationships, resulting in very low feature capture rates for rapid actions (such as gestures) in short videos. Panagiotis ‘s15multimodal system employs CNNs for audio feature extraction, ResNet-50 for visual feature extraction, and utilizes LSTMs to process emotional context. However, this approach primarily focuses on “short-term emotion recognition,” and the temporal memory window of the LSTM is insufficient to cover the 20 keyframes within a 15-second short video, failing to capture the long-term behavioral patterns required for personality analysis.Duan16 proposed a multimodal surface personality analysis method integrating neural networks and random forests. For visual modality analysis, the ConvNeXt network was enhanced by introducing an ECA attention mechanism, with a novel architectural module (ECblock) developed to extract personality-relevant features. To address the temporal characteristics of short videos, the modified ConvNeXt was combined with gated recurrent units (GRUs) for personality trait assessment. In auditory modality processing, acoustic features were manually extracted using the librosa toolkit, followed by personality prediction through a grid-searched random forest model, However, the gating mechanism of GRU exhibits a weaker capability than attention mechanisms in capturing local inter-frame dependencies.Zhao17 proposed a hybrid deep learning framework integrating convolutional neural networks (CNNs), bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM), and Transformer networks. A pre-trained deep audio CNN model (VGGish) was employed to learn high-level acoustic features, while a pre-trained facial CNN model (VGG-Face) separately extracted global scene features and localized facial features from dynamic video frames. The derived audiovisual features were processed through Bi-LSTM and Transformer architectures to capture long-term temporal dependencies, generating final global audio-visual representations. Personality trait recognition was implemented via linear regression for unimodal analysis (audio/visual), followed by decision-level fusion to produce Big Five personality scores and interview performance scores. Current methodologies exhibit limitations in capturing critical temporal action details within rapidly evolving scenarios. Furthermore, prevalent approaches relying on simplistic attention mechanisms inadequately model complex temporal interdependencies across frames, resulting in suboptimal information integration.

Current research is primarily distributed across three major areas: multimodal emotion/short-term state recognition, single-modality static visual tasks, and data support for personality recognition. While these fields have accumulated significant technical expertise in their respective directions, they all exhibit an adaptation gap when compared to the requirements of this study on “dynamic bimodal long-term personality recognition.” In the field of multimodal emotion and short-term state recognition, Zhu et al.18 proposed RMER-DT, which reconstructs missing modalities in dialogue via conditional diffusion and balances modality weights using a hierarchical Transformer. Wang et al.19 introduced RAFT, which employs cross-attention to fuse text-audio features and enhances robustness through adversarial training with noise simulation. Wang et al.20 developed CIME, which uses text-enhanced attention to associate audio-visual information and models speaker interactions via graph convolutional networks. Wang et al.21improved the accuracy of multimodal sentiment analysis by employing intra-modal contrastive learning to remove negative information. However, such methods commonly focus on “short-term emotion or dialogue state recognition,” lacking the capability to capture “long-term behavioral patterns across 20 frames in 15-second short videos.” Moreover, they partially rely on the text modality, making them incompatible with the core requirements of personality recognition, which demands “no text dependency and reliance on long-term behavior statistics.” In the field of single-modality static visual tasks, Huang et al.22 proposed ADGL, which employs MS-iTransformer to capture long-term station and BSTA to construct a global spatiotemporal graph for PM₂.₅ prediction. Wang et al.23 developed KGD, which balances road segmentation accuracy through knowledge distillation and MS-LSA. Ye et al. ‘s24 FedDG-VECA, Gao et al. ‘s25SRTNet, Guo et al. ‘s26 SKSHA-Net, and Song et al. ‘s27 FRENet respectively optimized performance in fundus segmentation, image super-resolution, and deepfake detection. However, these studies are all designed for single-modality static tasks, lacking multimodal collaboration and dynamic temporal modeling capabilities, making them difficult to adapt to the requirement of fusing bimodal dynamic features of “visual micro-expressions + audio prosody” for personality recognition. In research related to personality recognition support, Zhu et al. ‘s28 client-server system enables non-contact acquisition of facial videos and behavioral sequences for remote emotion assessment, but it relies on a distributed architecture and focuses on short-term state recognition. Zheng et al. ‘s29 DSGAD addresses graph anomaly detection through dynamic wavelets but lacks a multimodal design. Jiang et al.30 constructed the CHAIRS dataset, which provides dynamic correlation data for “full-body articulated human-object interaction,” thereby addressing the limitation of First Impression V1 that solely focuses on facial regions and offering support for subsequent pose feature extraction in special populations. In summary, existing research commonly exhibits a core gap of “failing to balance dynamic bimodal and long-term behavior capture,” which is precisely the motivation for designing the DLF multi-scale network model in this paper—by employing the DWTC module to extract visual multi-scale dynamic features, the LMSA module to achieve audio-visual temporal alignment, and the decision layer to accomplish bimodal fusion, in order to fill the technical void in “dynamic bimodal long-term personality recognition.”

Therefore, the contributions of this study can be summarized in the following directions:

-

1.

In video keyframe feature extraction, traditional methods often lose structural information when directly merging upsampled small-scale feature maps with large-scale ones, making it difficult to balance global contours and local details. This paper proposes an improved multi-scale wavelet fusion (DWT) scheme combined with CNN: a 224 × 224 image is first decomposed into one low-frequency subband (LL, representing global structure) and three high-frequency subbands (LH/HL/HH, representing local details). After customized processing, the subbands are fused back to the original size via inverse discrete wavelet transform (IDWT) and then input into a CNN to mine deep semantic features. This approach effectively enhances the capture of both global and local details, laying a foundation for personality-related feature extraction.

-

2.

After extracting the feature sequence, traditional methods struggle to capture inter-frame temporal and content relationships, leading to insufficient information integration. This paper improves the Lightweight Multi-scale Adapter (LMSA): the feature sequence is used to generate Queries (Q), Keys (K), and Values (V), which are split into multi-head attention. Invalid associations are masked using a local window mask (window size W = 3). After attention calculation and weight normalization, the multi-head outputs are merged, enabling precise analysis of temporal step feature relationships and achieving efficient integration of sequence information.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Chap. 1 introduces the research background, Chap. 2 reviews related work, Chap. 3 details the dataset processing methodology and elaborates the proposed DLF multiscale network model, Chap. 4 presents experimental data, configurations, results, and analytical interpretations, Chap. 5 provides visualization analysis of experimental outcomes, Chap. 6 concludes the study, Chap. 7 provides an overview of prior research and future developments.and Chap. 8 contains the funding.

Proposed methodology

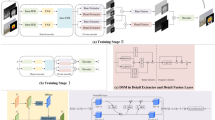

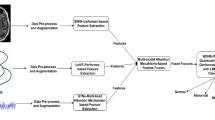

To achieve multiscale recognition of personality traits in video subjects, this study proposes a deep learning-based multimodal personality recognition method. The approach constructs a DLF multiscale network model that effectively integrates auditory and visual modalities. Figure 1 illustrates the workflow of the proposed method. As depicted, the system accepts dual-modality inputs: audio signals and visual signals. By implementing this multimodal fusion strategy, the model captures rich hierarchical features of video subjects across diverse scales and perspectives, thereby enhancing the precision of personality trait recognition.

Data preprocessing

Audio data preprocessing

Audio features are a series of numerical values extracted from audio signals, representing specific attributes or characteristics of the signals for tasks such as audio analysis, processing, and recognition. In the context of personality trait recognition, audio features can help us understand behavioral and emotional patterns exhibited by individuals through their speech. Fundamental Frequency: Refers to the pitch of a sound, typically associated with the vibration frequency of an individual’s vocal folds. Energy: Reflects the loudness or intensity of an audio signal. Variations in energy during speech can indicate the speaker’s vitality level or emotional intensity. Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs)31: A widely used audio feature that mimics the human ear’s perception of sound. MFCCs capture the timbre and resonance characteristics of speech signals. Timbre: Describes the quality or “color” of a sound, determined by its spectral composition. Speech Rate: The speed of speech, typically measured as the number of syllables uttered per second. Prosody: The rhythmic and intonation patterns of speech. Prosody serves as a critical medium for expressing emotions and intentions, with different emotional states manifesting through distinct prosodic patterns. Speech Pauses: Silent intervals occurring during speech production.

For speech feature extraction from video data, the FFmpeg toolkit32 is first employed to precisely isolate the audio track from the video stream. Subsequently, the openSMILE library33is utilized to extract critical acoustic feature information from the audio. In FFmpeg parameter configuration, this study configures the audio channels to 2 (stereo), sampling frequency to 44,100 Hz, and audio bitrate to 1,411 kbps to ensure high-quality audio output. The extracted audio files exhibit an average storage cost of approximately 2.57 MB per file on disk, providing substantial data for subsequent audio analysis. The feature set employs eGeMAPS (extended Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set), which comprises 88-dimensional core acoustic features including fundamental frequency (F0), audio energy, and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs). After PCA dimensionality reduction, 26 dimensions are retained to align with the existing feature dimensionality. A window size of 20 ms with a Hanning window is applied to suppress spectral leakage, balancing temporal resolution (for capturing short-term prosodic variations) and frequency resolution (for distinguishing different acoustic characteristics). A hop size of 10 ms ensures 50% overlap between adjacent windows, preventing the omission of acoustic details such as vocal pitch transitions and maintaining feature extraction continuity. In the post-processing stage, Z-score normalization is performed based on the training set’s mean and standard deviation to eliminate scale differences. The final output is a 26-dimensional feature vector compatible with the existing audio feature format in the code.establishing a robust foundation for in-depth analysis of speaker personality traits.

Video data processing

To effectively reduce data volume while preserving the core content of the video, we adopted a uniform sampling strategy based on OpenCV. This method extracts 20 key frames at equal intervals from the effective sequence of a 15-second, 30fps video (450 frames in total, adopts the ‘rounding + head/tail frame padding’ strategy). The complete images are read and undergo transformations such as resizing (224 × 224) and normalization, with the video frame background retained. This method not only significantly reduces the computational complexity of data processing but also ensures comprehensive coverage of the entire video by uniformly sampling all temporal segments. All extracted frames were resized to 224 × 224 pixels to optimize compatibility with subsequent facial feature recognition models, thereby enabling accurate facial feature analysis.

DLF multi-scale network framework

DWTC visual feature extraction

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) (mother wavelet type: Haar)34, leveraging its multi-scale decomposition capability, can precisely decompose an image (224 × 224) into feature components at different resolutions. This process preserves global structural information (such as overall facial contours) while capturing local textures and edge details (e.g., micro-expressions). When DWT is combined with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), the multi-scale feature representation ability of the former complements the deep semantic extraction capability of the latter. This synergy effectively uncovers correlative information among features at different scales, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s accuracy and robustness in identifying visual cues related to personality traits.

The operational workflow is as follows: The input image is first processed through average pooling (Avgpool) to generate a reduced-dimension feature map, which is then upsampled (Up) to restore spatial resolution. Meanwhile, the input image is separately fed into a Global Feature Extraction Block and a Local Feature Extraction Block to extract global and local features, respectively, followed by feature fusion. The fused feature map is concatenated with the upsampled feature map along the channel dimension and further processed through convolutional layers (Conv) for feature refinement. The convolved features are enhanced via a Channel Attention Module to emphasize critical channels. Finally, the refined features undergo pooling (Pool) and fully connected layers (Fc) to generate the final feature representation. The schematic diagram of this module is illustrated in Fig. 2.

DWT decomposition

The original image I(x,y)\(\:{\text{R}}^{H\times\:W}\)is decomposed by the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) into one low-frequency subband (LL) and three high-frequency detail subbands (LH, HL, HH).

The low-frequency subband (LLj) is generated by the scaling function ϕ and corresponds to global structures:

Here, \(\:{2}^{j}\:\)is the scale normalization factor (ensuring energy consistency of the basis functions across different scales), and \(\:\mathbf{k}=({k}_{1},{k}_{2})\)is the translation vector, corresponding to the pixel positions in the LLj subband.

High-frequency detail subbands: Generated by wavelet functions in three directions \(\:\left({\psi\:}^{\text{H}/\text{V}/\text{D}}\right)\), corresponding to local details:

Horizontal detail (LHj, Low-pass filtering in the row direction + high-pass filtering in the column direction)

Vertical detail (HLj, High-pass filtering in the row direction + Low-pass filtering in the column direction).

Diagonal detail (HHj, High-pass filtering in both the row and column directions)

Downsampling factor: After each level of DWT decomposition, all subbands (LLj,LHj,HLj,HHj) undergo 2 × 2 downsampling (selecting even-indexed pixels along both row and column directions), with a downsampling factor of 2. Consequently, the dimensions of LLj are H/(2j)×W/(2j).

Boundary handling: Symmetric Padding is employed (superior to zero padding as it avoids edge information distortion). Specifically, virtual pixels outside the image boundary are replicated symmetrically based on the edge pixels, ensuring that the decomposed subband dimensions align with the downsampling rules.

IDWT reconstruction

Reconstruct the LL subband at scalej(LLj) from the LL subband at scale j + 1 (LLj+1) and the three high-frequency subbands (LHj+1,HLj+1,HHj+1).

Prior to reconstruction, all subbands(LHj+1,HLj+1,HHj+1) undergo 2 × 2 upsampling (inserting zero values between each pixel along the row and column directions; upsampling factor is 2). Convolution is then performed with the reconstruction filters (the dual filters corresponding to φ and ψH/V/D)), and the results are superimposed to obtain LLj.

Subband routing fusion

After DWT decomposition, four subbands are obtained: one low-frequency subband and three high-frequency subbands.

The low-frequency subband (LLj) is input into the global feature extraction block: a 3 × 3 convolution (stride = 1, padding = 1) captures global structures, followed by BatchNorm and ReLU activation.

The high-frequency subbands (LHj+1,HLj+1,HHj+1) are input into the local feature extraction block: a 1 × 1 convolution is first applied for dimensionality reduction (to decrease parameters), followed by a 3 × 3 depthwise separable convolution (stride = 1, padding = 1) to capture local details.

Subband fusion: Global features and local features are concatenated along the channel dimension. After concatenation, the total number of channels equals the sum of the channel counts of the global features and the local features.

Convolutional neural network (CNN)

Given the input feature tensor \(\:X\in\:{\text{R}}^{N\times\:{C}_{in}\times\:{H}_{in}\times\:{W}_{in}}\) (where N is the batch size, \(\:{C}_{in}\)is the number of input channels, \(\:{H}_{in}\:\)is the input height, and \(\:{W}_{in}\:\)is the input width), the convolution kerne \(\:W\in\:{R}^{{C}_{out}\times\:{C}_{in}\times\:{K}_{h}\times\:{K}_{w}}\) (where Cout is the number of output channels, Kh is the kernel height, and \(\:{K}_{w}\) is the kernel width), the bias \(\:b\in\:{\text{R}}^{{C}_{\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}},\) the s=(sh,sw) (vertical/horizontal stride), the padding p=(ph,pw) (vertical/horizontal padding), and the activation function f(⋅), then the element-wise calculation formula for the CNN output tensor \(\:Y\in\:{\text{R}}^{N\times\:{C}_{\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\times\:{H}_{\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\times\:{W}_{\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}}\:\)is:

LMSA feature serialisation alignment

Local Multi-Head Self-Attention (LMSA) significantly enhances model performance and robustness in processing temporally ordered and contextually correlated feature sequences by capturing dependency relationships within time-series data. In video or sequential data, features across different frames exhibit temporal ordering and content-based correlations. LMSA employs attention mechanisms to model these dependencies, thereby enabling more effective integration of information within the sequence. By analyzing the relevance between features at each timestep and those at other timesteps, LMSA efficiently leverages temporal sequence characteristics. The operational workflow is as follows: Input embeddings are first transformed into queries, keys, and values through three linear layers, then split into multiple heads for independent attention computation. Within each head, attention scores are calculated via dot products between queries and keys, followed by the application of a local window mask to restrict the attention scope. The scores are normalized using softmax, and the weighted sum of values is computed to generate the output. The outputs from all heads are concatenated and passed through a final linear layer to produce temporally aligned and feature-enhanced representations. The schematic diagram of this module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Input representation

Let the input sequence be \(\:X\in\:{\text{R}}^{B\times\:N\times\:C}\), where B is the batch size, N is the length of the sequence(this is 20),and C is the embedding dimension.

-

1.

Linear transformation.

Linear transformations of Query, Key and Value are performed on the input sequence X respectively:

-

2.

Multi-attention mechanisms.

Divide the transformed Q,K,V into H attention heads (num_heads), each with dimension d = C/H (head_dim):

Each head focuses on a specific subspace of the feature sequence, and multi-head parallel computation enables coverage of a more comprehensive range of inter-frame correlation patterns.

Formal definition of local window masking

-

1.

Window Index Range.

The local window size is denoted as W(window_size, representing the maximum number of frames a single frame can associate with). In the experiment,W = 3 is set (indicating that the current frame only attends to “itself, one preceding frame and one following frame”, totaling a 3-frame range). For the i-th keyframe in the sequence (i∈[1,N], N = 20), the closed interval of its effectively associated frames j is:

Sequence Head (i ≤ W − 1): The left boundary of the window contracts to 1 to avoid out-of-bounds access.

Sequence Tail (i ≥ N − W + 1): The right boundary of the window contracts to N to avoid out-of-bounds access.

Sequence Middle Segment (W ≤ i ≤ N−W + 1):The window forms a complete closed interval.

-

2.

Mask Matrix.

Construct an N×N mask matrix M∈{0,−∞}N×N to mark “valid associations” and “invalid associations,” as defined by the following formula:

M[i, j] = 0: Indicates a valid association between the i-th frame and the j-th frame, preserving the subsequent attention score calculation result.

M[i, j] = −∞: Indicates an invalid association between the i-th frame and the j-th frame, where exp(−∞) ≈ 0 subsequently masks its contribution to the attention weights, ensuring that only frames within the local window participate in the association calculation.

Attention, masking, and normalization

-

1.

For each head h, compute the attention scores.

In theh-th head, the “raw attention score” of the i-th element with respect to the j-th element integrates three key operations: dot product, scaling, and masking. This score is subsequently normalized via softmax to obtain the attention weight, which is then used to compute a weighted sum over the value vectors V, yielding the final attention output for that head.

-

2.

Apply masking and normalization.

Probabilistic attention weights, with Softmax normalization applied to the scores of each head.

Win(i): The local effective window for the i-th frame, defined as Win(i)=[max(1,i − W + 1),min(N,i + W − 1)]; the summation over j’is performed only within this window.exp(·): The exponential function, which “amplifies score differences”—valid associations with high scores are further enhanced, while invalid associations (-∞) are transformed into exp(-∞) ≈ 0, thus not affecting the summation.Normalization effect: attn[h,i,j]∈[0,1], and\(\:\:\sum\:_{{j}^{{\prime\:}}\in\:\text{W}\text{i}\text{n}\left(i\right)}\:\text{a}\text{t}\text{t}\text{n}[h,i,{j}^{{\prime\:}}]=1\), representing the “attention probability” that the h-th head pays from the i-th frame to the j-th frame. A higher probability indicates a greater contribution of the j-th frame’s features to the i-th frame.

-

3.

Perform weighted summation and head merging.

The value vectors of each header are weighted and summed, and then the outputs of all the headers are spliced and linearly transformed:

where \(\:{W}_{0}\in\:{\text{R}}^{C\times\:C}\) is the learnable weight matrix used to merge the multiple outputs.

The final output is the output of the local multi-head self-attention mechanism.

-

4.

Complexity verification.

For single-head attention, each position i only computes over W valid frames, resulting in a complexity of O(NWd) (where d is the single-head dimension).

Auditory feature extraction

The auditory feature module aims to extract feature representations with high discriminability and compactness from input audio data. This module adopts a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) structure comprising three fully connected (FC) layers. The input layer receives a 26-dimensional audio feature vector. After processing through the first FC layer, the feature dimension is mapped to 512, with the computational formula expressed as:

Where \(\:\text{x}\in\:{\text{R}}^{26}\)is the input audio feature vector, \(\:{\text{W}}_{1}\in\:{\text{R}}^{512\times\:26}\)is the weight matrix.\(\:{\text{b}}_{1}\in\:{\text{R}}^{512}\) is a bias term.Next, the batch normalisation and ReLU activation function are applied:

The second fully connected layer reduces the feature dimensions from 512 to 256 and is calculated as:

After applying the same batch normalisation and ReLU activation function, a Dropout layer is added to prevent overfitting:

The third fully connected layer further reduces the feature dimension to 128, calculated as:

The final output audio feature vector \(\:{\text{h}}_{3}\in\:{\text{R}}^{128}\) provides a high-quality audio feature representation for subsequent multimodal fusion. way of enhancing the performance of the entire multimodal model.

Fusion strategy

Decision Fusion enhances the model’s predictive performance by integrating information from heterogeneous data sources (e.g., video and audio). In this specific implementation, the model first processes each modality independently: video data undergoes feature extraction via a visual model, while audio data is processed through an audio model that may incorporate fully connected layers or other layers suitable for sequential data processing.

For video data V and audio data A, the features are extracted by their respective models:

Vision Model refers to a video processing model. and \(\:{\theta\:}_{v}\) represents the parameters of the video model.

AudioModel denotes the audio processing model, which may incorporate fully connected (FC) layers or other layers suitable for sequential data processing, and \(\:{\theta\:}_{a}\) represents the parameters of the audio mode.

After feature extraction, the two sets of features are concatenated along the feature dimension, i.e., they are combined into a longer vector via torch.cat. This concatenation operation is based on the hypothesis that features from different modalities are complementary in the fused vector, implying that they jointly provide richer information than unimodal features alone.

concat denotes the concatenation operation of feature vectors, joining video features Fv and audio features Fa into a longer vector F.

The spliced feature vectors are then processed through one or more neural network layers that contain linear transformations, activation functions, and regularisation techniques, with ReLU activation functions and Dropout layers in between. Finally, the output of the fusion layer is transformed into the final prediction by an activation function.

Fusion feature processing, where the spliced feature vector F is processed through one or more neural network layers:

where \(\:{W}_{1}\) and \(\:{W}_{2}\:\)are the weight matrices, \(\:{b}_{1}\)and \(\:{b}_{2}\) are the bias terms, ReLU is the activation function, and σ is the final activation function.

The strength of this fusion approach lies in its ability to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness by leveraging complementary information across different modalities. By integrating features from heterogeneous data sources (e.g., visual and auditory), the model capitalizes on cross-modal synergies, where each modality compensates for potential weaknesses in others. Simultaneously, this strategy preserves modality-specific processing pipelines, allowing independent feature extraction followed by flexible feature combination. This modular design provides substantial flexibility for architectural optimization and task-specific adaptation.

Experimental setup

In this section, we first present the relevant datasets, followed by a systematic analysis of the baseline methodology. We also provide a comprehensive description of the experimental implementation details, including feature preprocessing procedures, parameter configuration specifications, and evaluation metrics definitions to ensure the reproducibility of our findings.

Data sets

Personality trait analysis in video datasets remains relatively underexplored. In this study, the primary dataset employed is the First Impression V137, comprising 10,000 video clips with an average duration of 15 s, extracted from 3,000 distinct high-definition (HD) YouTube videos. These recordings feature individuals facing and speaking directly to the camera in English. The dataset is split in a 3:1:1 ratio into a training set (6,000 videos), a validation set (2,000 videos), and a test set (2,000 videos). The subjects included in the dataset cover different genders, ages, nationalities, and ethnicities. To prevent data leakage and ensure an objective evaluation of the model’s generalization capability, a speaker-disjoint strategy is adopted—subjects appearing in the training set do not appear in the validation or test sets. Annotated metadata includes gender labels (male = 1, female = 2) and ethnic classifications (Asian = 1, Caucasian = 2, African-American = 3). Personality trait annotations are grounded in the Big Five personality model, quantifying five psychological dimensions: Openness (O), Agreeableness (A), Extraversion (E), Neuroticism (N), and Conscientiousness (C). Each dimension is represented by continuous scores normalized between 0 and 1, generated through crowdsourced evaluations via Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT). A schematic visualization of the dataset structure is presented in Fig. 4.

Realisation details

In terms of feature preprocessing, recent benchmark tests in literature indicate that most models show no significant performance difference when using facial regions versus full video frames. This suggests that the choice between these two approaches has limited impact on model performance. However, while background and spatial context may provide certain personality-related information, they could simultaneously introduce noise unrelated to personality, potentially negatively affecting model accuracy. For data processing, we first load preprocessed multimodal data including video frame images and audio data. Regarding model architecture, DWTC is employed as the visual feature extractor, combined with an audio model for multimodal fusion. In parameter configuration, the L1 loss is adopted as the loss function during training phase, with AdamW optimizer for parameter updates and a cosine annealing with warm restarts learning rate scheduler for dynamic learning rate adjustment. During training, loss and accuracy metrics are recorded and printed at regular batch intervals. After each epoch completion, model weights are saved and evaluated on the validation set.

Rating indicators

-

1.

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average absolute deviation between predicted values and true values. A smaller value indicates a smaller prediction deviation.

-

2.

Mean Squared Error (MSE): By squaring the errors, it amplifies the impact of larger deviations, making it more sensitive to extreme error conditions

-

3.

Coefficient of Determination (R²): Measures the model’s ability to explain the variance in the data.

where ȳ is the mean of the true values. Its value ranges from 0 to 1.

-

4.

Accuracy: Measures the correctness of model predictions.

Set the maximum allowable error (max_diff) to 0.1: based on the natural error range of AMT crowd-sourced annotations (inter-annotator differences in personality ratings for the same subject typically fall within ± 0.1). This threshold balances the rigor and rationality of the evaluation.

Prediction Correctness Determination: A prediction for the i-th sample is considered correct if the predicted personality trait value (\(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\)) and the true value (yi) satisfy ∣\(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\)−\(\:{y}_{i}\)∣≤max_diff.

where I(⋅) denotes the indicator function (which takes the value 1 if the condition is satisfied and 0 otherwise), and n represents the total number of samples.

-

5.

95% Confidence Interval: 95% CI.

Where \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) is the sample mean, K s the number of random seed runs, and \(\:{\text{M}\text{A}\text{E}}_{i}\:\)is the MAE result of the i-th seed.

Where α corresponds to the 95% confidence level, and df = K − 1 represents the degrees of freedom, obtained by consulting the t-distribution table.

Standard Error (SE):

Where s is the sample standard deviation.

Experimental visualisation and analysis

In this section, experiments are conducted on the ChaLearn First Impressions V1 dataset to evaluate the performance of the DLF multi-scale network model. The effectiveness of the DLF multi-scale network is assessed through comparisons with other baseline methods, and the results of ablation studies are interpreted.

Comparison of different modal ablation experiments

Table 1—Audio-modality personality recognition by separately using MLP, LMSA alone, and the cascaded MLP + LMSA. Experimental results show that the fused MLP + LMSA approach significantly outperforms either individual path. The rationale is as follows: as a three-layer fully connected network, MLP first maps 26-dimensional low-level acoustic features to 128-dimensional high-level representations, sufficiently exploring nonlinear cues highly correlated with personality (e.g., F0, energy, MFCCs). However, MLP is insensitive to temporal context, causing a maximum systematic bias of approximately 0.015 in the “Neuroticism” dimension. LMSA, through local multi-head self-attention, re-weights speech features as sequences, capturing dynamic prosodic patterns within a 3-frame window and compensating for MLP’s temporal blindness. Yet, LMSA itself lacks the ability to extract deep semantics from individual frames, leading to underfitting of about 0.01 in dimensions requiring fine tonal nuances (e.g., “Agreeableness”). By cascading the two, MLP first outputs high-quality frame-level representations, and LMSA then computes local dependencies on these representations. This preserves MLP’s nonlinear advantages while incorporating LMSA’s sequential consistency constraints, thereby reducing the mean absolute error by approximately 0.004 and achieving complementary gains. This collaborative design of “deep features + lightweight attention” provides a concise and effective baseline paradigm for estimating Big Five personality traits using audio signals alone.

Table 2—Video-modality personality recognition compares the performance of using DWTC alone, LMSA alone, SWINT + LMSA, and DWTC + LMSA. Experimental results demonstrate that the DWTC + LMSA approach significantly outperforms other combinations. The underlying rationale is as follows: DWTC employs discrete wavelet transform to decompose a 224 × 224 frame into low-frequency global contours and high-frequency micro-expression details, then uses CNN to extract semantically sTable 128-dimensional frame-level vectors, effectively leveraging multi-scale cues strongly correlated with facial morphology and personality. However, DWTC is insensitive to frame sequencing, particularly manifesting as jittery predictions in the “Conscientiousness” dimension. LMSA addresses this by applying local multi-head self-attention to reweight 20 feature segments within a 3-frame window, yet it underfits by approximately 0.01 for dimensions like “Agreeableness” that rely on subtle curvature variations (e.g., mouth corners). By feeding DWTC’s high-quality frame-level representations to LMSA, the combined approach compensates for DWTC’s inter-frame memory gap while avoiding LMSA’s miscalibrated weighting on shallow features, ultimately reducing the mean absolute error by about 0.003 and achieving a moderate yet stable complementary effect. Notably, SWINT + LMSA shows a slight advantage in the “Neuroticism” dimension, suggesting that window-based Transformers remain competitive in capturing subtle cues like eye tremors. Overall, however, DWTC + LMSA provides a more balanced solution for video unimodal scenarios.

Comparison of multimodal fusion approaches

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, and 5, Early fusion, voting fusion, and decision-level fusion exhibit significant performance differences due to their distinct fusion logic and stages. Early fusion forcibly concatenates visual and audio features after extraction. While simple in process, it is constrained by differences in feature dimensions and physical meanings between modalities, easily introducing redundant information and spatiotemporal misalignment issues. This leads to clear limitations in the optimal combination’s average accuracy and creates a contradiction where “data explanatory power (R²) is relatively high but practical predictive accuracy is insufficient.” Voting fusion, which applies simple weighted or equal-weight voting to unimodal results after model prediction, fails to consider the confidence differences of various models across different personality traits. It is unsuitable for the continuous scoring requirement of the Big Five model and struggles to highlight the role of dominant modalities, resulting in weak robustness and an average accuracy lower than decision-level fusion. Decision-level fusion adopts a “unimodal independent optimization dynamic weighted integration” logic. It allows the visual model to focus on mining multi-scale features and the audio model to concentrate on extracting acoustic nonlinear features first, then dynamically allocates weights based on each modality’s performance across different traits, effectively avoiding the pitfalls of the previous two methods. Its optimal combination’s average accuracy shows significant improvement over early fusion, with particularly outstanding accuracy gains in core personality traits (e.g., Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism). Furthermore, the accuracy fluctuation across traits is much smaller than the former two methods, achieving a better balance between “predictive accuracy” and “data explanatory power.” Consequently, it emerges as the optimal choice among the three fusion strategies for audio-visual multimodal personality recognition, further validating that the complementary nature of multi-scale visual features and temporally aligned audio features can only be fully leveraged through dynamic weighting.

Comparison of DWTC and feature extraction methods

As shown in Table 6, Under the fixed conditions of visual modality + LMSA (window = 3, heads = 4) + AdamW (lr = 1e-4) + L1 loss + batch size = 32, validates the effectiveness of the proposed DWTC multi-scale visual feature extraction module. DWTC comprehensively outperforms all comparative methods, achieving an average accuracy of 0.9177, an R² of 0.9043, and reducing the MAE to 0.1633. Its advantages are particularly significant in the Extraversion (E) and Agreeableness (A) dimensions, fully demonstrating its capability to simultaneously capture global facial contours and micro-expression details via wavelet decomposition. In contrast, the traditional Gabor Pyramid (GP) and Bandpass Filtering (BP) suffer from high-frequency information smoothing, resulting in MAE increases of approximately 0.011–0.014. Learnable Wavelets (LW) are prone to overfitting on the First Impressions dataset, leading to a decrease in average accuracy of 0.0127. Conventional Downsampling (CD), which directly discards crucial details, performs the worst. A paired t-test (p < 0.05) further confirms that DWTC’s leading advantage is statistically significant, thereby establishing a reliable and efficient visual representation foundation for subsequent multimodal decision-level fusion.

Parameter optimization for LMSA window size and number of heads

As shown in Table 7, under fixed conditions—DWTC visual module, decision-level fusion, AdamW (lr = 1e-4), L1 loss, and batch size = 32—and based on the processing logic of “audio-visual offline separation → independent feature extraction → decision-level fusion,” where separated audio and video lose original temporal relationships and no real-time timestamp mapping is preserved during feature extraction, the window size W is determined based on fixed offline scene characteristics rather than real-time dynamic temporal information. Experimental variable 1: window size (W) tested at 1 (current frame only), 3 (current frame ± 1 frame), 5 (current frame ± 2 frames), and 7 (current frame ± 3 frames), with the number of heads fixed at H = 4. W = 1 only aligns single-frame features, failing to capture inter-frame correlations (e.g., Extraversion’s “gesture-expression” coherence or Neuroticism’s “eye micro-tremors”), resulting in incomplete feature alignment and poor performance (Avg = 0.8825, R²=0.8814); the low MAE (0.1542) stems from conservative predictions due to insufficient features, inadequate for personality recognition’s long-term behavioral cue requirements. W = 3 (optimal in this study) focuses on the “current frame ± 1 frame,” precisely aligning micro-expressions (e.g., subtle smiles, eyebrow movements) and short-term body motions without redundant noise, achieving the best performance (Avg = 0.9177) and a Neuroticism (N) dimension accuracy of 0.9182. W = 5/W = 7 (larger windows) expand alignment but introduce redundant frames (e.g., scene transitions, irrelevant object movements), diluting effective features and reducing performance (e.g., W = 7: Avg = 0.8958, MAE = 0.1731; Conscientiousness (C) accuracy drops from 0.9160 to 0.8972 due to interference from irrelevant frames). Based on the non-real-timestamp experimental workflow and First Impressions V1 dataset results, W = 3 is the universally optimal choice for the 20-frame offline sampling personality recognition task, covering core “micro-expression–short-term action” dynamics.

As shown in Table 8, For variable 2: number of heads (H) tested at 1, 2, 4, and 8 with fixed W = 3, H = 4 efficiently covers multi-subspace personality correlation features—H < 4 fails to capture trait-specific feature associations simultaneously, while H = 8 yields negligible Avg gain (+ 0.0004) with low parameter efficiency, making H = 4 optimal.

To determine the optimal configuration of the window size (W) and the number of heads (H) for the LMSA module, a cross-combination experiment was conducted using the strategy of “fixing one parameter while optimizing the other” (e.g., fixing H to adjust W, and fixing W to adjust H), followed by multiple rounds of repeated validation. The results indicate that when W = 3 and H = 4, the model achieves the highest average accuracy and strong stability. This combination enables precise capture of local features while avoiding noise interference through W = 3, and facilitates multi-dimensional feature learning with H = 4, aligning with the goal of efficient feature extraction in LMSA. Consequently, (W = 3, H = 4) is determined as the optimal configuration. As shown in Fig. 5.

Wavelet-based qualitative visualization

As shown in Fig. 6, the qualitative visualization of wavelet subbands combined with quantitative analysis using Pearson correlation coefficients for high Agreeableness (A) samples intuitively and rigorously demonstrates the relationship between DWT decomposition subbands and personality cues, supporting the effectiveness of the DLF model’s multi-scale feature extraction. The original frame displays typical Agreeableness micro-expressions such as subtle smiling and relaxed eyebrows, providing a visual foundation for correlation analysis. The LL subband (low-frequency) retains the global facial outline, aiding in the assessment of Extraversion through “posture openness.” The LH subband (horizontal high-frequency) captures details of eyebrow relaxation, showing a correlation coefficient of r = 0.65 (p < 0.01) with Extraversion scores, quantitatively verifying its ability to capture personality-related micro-expressions. The HL subband (vertical high-frequency) focuses on the edges of smile curvature, correlating with Agreeableness scores at r = 0.72 (p < 0.01), providing key evidence for trait recognition. The HH subband (diagonal high-frequency) reveals stable texture patterns around the eyes, correlating negatively with Neuroticism scores at r=−0.68 (p < 0.01), explaining its capacity to capture signals of emotional fluctuations. This chain of “original frame → subband features → quantitative validation personality correlation” proves that the DWTC module accurately separates global and local details, with high-frequency subbands establishing stable relationships with specific personality traits. This provides highly discriminative features for decision-level fusion, ultimately supporting the model’s achievement of an average accuracy of 0.9177 in Big Five personality recognition.

Calibration plots for the five major traits

The model exhibits significant differences in predictive performance across the Big Five personality traits, which is closely related to the inherent measurability, clarity of characteristic signals, and intrinsic complexity of each trait. Conscientiousness shows the best predictive performance, with an MAE of only 0.1606 and 38.5% of samples falling within the acceptable error margin of ± 0.1. This is because its core characteristics—such as goal orientation and self-discipline—are highly observable and anchored in stable behavioral cues, enabling the model to establish a robust predictive logic. Neuroticism (MAE = 0.1618, 38.3% within acceptable error) and Extraversion (MAE = 0.1687, 35.2% within acceptable error) demonstrate moderate performance. While emotional instability signals in Neuroticism are identifiable, they are easily influenced by short-term contextual fluctuations; core features of Extraversion, such as social activity, are overt but overlap with signals of Agreeableness, both of which introduce some interference in prediction accuracy. Nevertheless, the distinctiveness of their core features still supports effective model learning. Openness shows relatively weaker predictive accuracy, with an MAE of 0.1696 and only 32.9% of samples meeting the acceptable error threshold. This stems from the highly individualized and broadly defined nature of openness to new ideas and experiences, resulting in dispersed characteristic signals and a lack of uniformly highly correlated predictors, compounded by cultural influences that increase feature extraction difficulty. Agreeableness is the most challenging dimension, with an MAE of 0.1723 and only 34.2% of samples within the acceptable error range. This is inherently due to a disconnect between theoretical definition and practical measurement: prosocial behaviors may stem from deep empathy or strategic compromise, and evaluation criteria are highly context-dependent and correlated with other traits, weakening feature specificity and making it difficult for the model to establish reliable predictive logic. These performance differences align with the personality psychology principle that “the more operable a trait is, the higher its measurement accuracy,” and provide direction for subsequent model optimization. As shown in Fig. 7.

Computational efficiency analysis

As shown in Table 9, SWINT + LMSA has 29.86 million parameters, 72.30 GFLOPs, an average accuracy (Avg) of 0.9045, a throughput of 2.5 samples/second, and a training time of 1.08 h per epoch. In comparison, DWTC + LMSA exhibits fewer parameters (29.03 million), lower GFLOPs (65.60), higher average accuracy (0.9177), the same throughput as SWINT + LMSA (2.5 samples/second), and a shorter training time per epoch (0.93 h). In summary, DWTC + LMSA achieves model lightweighting (reduced parameters and computational complexity), improved recognition performance (higher accuracy), and enhanced training efficiency (shorter training time per epoch) while maintaining the same throughput as SWINT + LMSA, demonstrating a superior balance between performance and computational efficiency.

Performance comparison

As shown in Table 10, the DLF multi-scale network model was compared with five categories of mainstream baseline models (including early handcrafted feature-based multimodal models, unimodal optimized models, deep residual dual-branch models, and hybrid deep learning architectures) on the ChaLearn First Impressions V1 dataset. The results demonstrate that its average accuracy (Avg = 0.9177) ranks the highest among all baselines. It significantly outperforms all baseline models in the dimensions of Extraversion (E = 0.9189), Agreeableness (A = 0.9198), and Neuroticism (N = 0.9182). The key reasons lie in the DWTC module’s ability to balance global visual structure with local micro-expression details, the LMSA module’s precise alignment of short-term audio-visual temporal relationships, and the decision layer’s dynamic allocation of modality weights, effectively compensating for the baseline models’ shortcomings in temporal synchronization and feature discriminability. The DLF model is only slightly inferior to the Zhao model in the dimensions of Conscientiousness (C = 0.9160) and Openness (O = 0.9159). The former is due to the limited window size of LMSA struggling to capture long-term behavioral sequences, while the latter stems from the lack of textual modality support for creativity-related expressive cues relevant to Openness. Overall, this comparison fully validates the effectiveness of the DLF’s “multi-scale feature extraction + temporal alignment + dynamic fusion” approach and also provides direction for future improvements, such as dynamically adjusting the LMSA window size and incorporating textual modality to enhance the model.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a DLF multi-scale network model architecture for analyzing personality traits of individuals in videos by extracting their visual and audio features. The approach employs discrete wavelet transform to capture both global and local features, combined with convolutional neural networks (CNN) to further extract deep semantic features. Meanwhile, the LMSA algorithm is utilized to achieve alignment and integration of feature sequences, and the model is constructed through decision-level fusion. Extensive experimental results on the First Impressions V1 dataset demonstrate the significant effectiveness of the proposed DLF multi-scale network model.

Limitations and future development

The First Impressions V1 dataset utilized in this study primarily consists of natural facial expressions and speech data from the general population, resulting in relatively insufficient coverage of special population samples, such as individuals with facial expression limitations (e.g., facial paralysis patients) or speech disorders (e.g., stuttering or aphasia). This makes it difficult to fully validate the model’s generalization capability for special populations through empirical experiments, and it is also challenging to accurately quantify the potential impact of special population data on recognition accuracy. Secondly, the study has certain limitations in directly processing video datasets, requiring a “audio-visual separation video frame sampling modality-specific feature extraction” pipeline. The frame sampling process may lead to the loss of critical dynamic information between frames (such as temporal variations in micro-expressions and body movements), which are important for personality trait recognition. At the same time, there is still a lack of sufficient technical and computational resources for directly extracting video features, preventing full exploitation of the inherent spatiotemporal information in videos, which imposes certain constraints on the practical application and expansion of the technology.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the ChaLearn LAP repository, https://chalearnlap.cvc.uab.cat/dataset/24/description/. The use of these data complies with the database’s Ethical Statement and Data Use Policy, which ensures informed consent from all participants and strict anonymization of personal information.”

References

Allport, G. W. Pattern and Growth in Personality (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961).

Cattell, R. B. The Description and Measurement of Personality (World Book Company, 1949).

Eysenck, H. J. The Dimensions of Personality (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. NEO PI-R Professional Manual (Psychological Assessment Resources, 1992).

Polzehl, T., Möller, S. & Metze, F. Automatically assessing personality from speech. In 2010 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Semantic Computing, 134–140 (2010).

Celli, F. Mining user personality in twitter. Language, Interaction and Computation CLIC, 1–5 (2011).

Mohammadi, G. & VINCIARELLI, A. Automatic personality perception: Prediction of trait attribution based on prosodic features extended abstract. In 2015 International conference on affective computing and intelligent interaction (ACII), 484–490 (2015).

Su, M. H. et al. Personality trait perception from speech signals using multiresolution analysis and convolutional neural networks. In 2017 AsiaPacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), 1532–1536 (2017).

Gürpinar, F., Kaya, H. & Salah, A. A. Combining deep facial and ambient features for first impression estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016 Workshops: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 8 10 and 1516, 2016, Proceedings, Part III 14, 372–385 (2016).

Beyan, C. et al. Personality traits classification using deep visual activitybased nonverbal features of keydynamic images. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 12 (4), 1084–1099 (2019).

Biel, J. I., Teijeiromosquera, L. & Gaticaperez, D. Facetube: predicting personality from facial expressions of emotion in online conversational video. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM international conference on Multimodal interaction, 53–56. 43 Dalian University for Nationalities Master’s Thesis References (2012).

Dhall, A. & Hoey, J. First impressionspredicting user personality from twitter profile images. In Proceedings of the Human Behavior Understanding: 7th International Workshop, HBU 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 16, 2016, Proceedings 7, 148–158 (2016).

Gülütürk, Y., Gülü, U., van Gerven, M. A. J. & van Lier, R. Deep impression: audiovisual deep residual networks for multimodal apparent personality trait recognition. arXiv:1609.05119v1 [cs.CV] (2016).

Zhang, C. L., Zhang, H., Wei, X. S. & Wu, J. Deep bimodal regression for apparent personality analysis. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2016 Workshops. ECCV 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science() Vol. 9915 (eds Hua, G. & Jégou, H.) (Springer, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49409-8_25.

Tzirakis, P., Trigeorgis, G., Nicolaou, M. A., Schuller, B. W. & Zafeiriou, S. End-to-end multimodal emotion recognition using deep neural networks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 11(8), 1301–1309. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2017.2764438 (2017).

Duan, X. et al. Multimodal Apparent Personality Traits Analysis of Short Video using Swin Transformer and Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory Network. In 2022 4th International Conference on Frontiers Technology of Information and Computer (ICFTIC), Qingdao, China, 2022, pp. 1003–1008. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICFTIC57696.2022.10075178

Zhao, X. et al. Integrating audio and visual modalities for multimodal personality trait recognition via hybrid deep learning. Front. NeuroSci. 16, 1107284 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. RMER-DT: Global-Local multimodal emotion recognition in conversational contexts based on diffusion and transformers. Inf. Fusion 123, 103268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103268 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. RAFT: robust adversarial fusion transformer for multimodal sentiment analysis. Array 27, 100445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.array.2025.100445 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. CIME: contextual Interaction-based multimodal emotion analysis with enhanced semantic information. Preprint https://doi.org/10.22541/au.173750886.60448227/v1 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Contrastive-Based removal of negative information in multimodal emotion analysis. Cogn. Comput. 17, 107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-025-10463-9 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. A dynamic Global–Local Spatiotemporal graph framework for Multi-City PM₂.₅ Long-Term forecasting. Remote Sens. 17 (16), 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17162750 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Knowledge generation and distillation for road segmentation in intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2025.3577794 (2025).

Liu, Y., Zhao, N., Zhu, Y., Wang, X. & Liu, J. Advancing federated domain generalization in ophthalmology: vision enhancement and consistency assurance for multicenter fundus image segmentation. Pattern Recogn. 169, 111993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111993 (2026).

Gao, M. et al. Towards trustworthy image Super-Resolution via symmetrical and recursive artificial neural network. Image Vis. Comput. 158, 105519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105519 (2025).

Guo, S., Li, Q., Gao, M., Zhu, X. & Rida, I. Generalizable deepfake detection via Spatial kernel selection and halo attention network. Image Vis. Comput. 160, 105582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105582 (2025).

Song, W. et al. Deepfake detection via feature refinement and enhancement network. Image Vis. Comput. 162, 105663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105663 (2025).

Zhu, X. et al. A client–server based recognition system: Non-contact single/multiple emotional and behavioral state assessment methods. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 260, 108564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108564 (2025).

Zheng, J. et al. Dynamic Spectral Graph Anomaly Detection. In The Thirty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-25), 13410–13418 (2025).

Jiang, N. et al. Full-Body Articulated Human-Object Interaction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 12456–12466 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Feature extraction process of Mel-frequency cepstrum coefficients for audio. Inform. Technol. Informatisation. 274, 104–111 (2023).

Huang, R. et al. An Algorithm for Correcting Video Audio Asynchronization Based on Syncnet. In IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology & Education (TALE), 01–04 (2021).

Eyben, F. & Schuller, B. Opensmile:): the Munich open-source large-scale multimedia feature extractor. ACM Sigmultimed. Rec. 6, 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/2729095.2729097 (2015).

Chen, G. et al. Bracketing Image Restoration and Enhancement with High-Low Frequency Decomposition. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 6097–6107 (2024).

Gorbova, J. et al. Automated screening of job candidate based on multimodal video processing. Proc. 2017 IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR 17). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2017.214 (2017).

Helm, D. & Kampel, M. Single-modal video analysis of personality traits using low-level visual features. In 2020 Tenth International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools.

Poncelópez, V. et al. Chalearn lap 2016: First round challenge on first impressionsdataset and results. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016 Workshops: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 810 and 1516, 2016, Proceedings, Part III 14, 400–418 (2016).

Funding

This work is partially supported by Research Project on Economic and Social Development of Liaoning Province(2024lsljdybkt-017), Liaoning Province Science and Technology Joint Plan (2024JH2/102600113),Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities(0919-140249) and Research project of China Federation of logistics and procurement (Grant No.:2024CSLKT3-020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N provide research direction, G doing experiments and writing, H processing data sets.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, T., Guo, Z. & Hou, Q. A DLF multi-scale quantitative research method for the big five personality traits. Sci Rep 16, 251 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27837-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27837-6