Abstract

Recently, particular attention has focused on the potential cardio-protective properties of dietary carotenoids. Here we aimed to evaluate the association between dietary intakes of carotenoids (α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin) and risk of dyslipidemia (elevated levels of total cholesterol (HTC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HLDL), triglycerides (HTG), or reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LHDL)) among adult participants of Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS). The present prospective cohort study was conducted in four separate analyses, HTG analysis with 1305 healthy adults, HLDL analysis with 1326 healthy adults, HTC analysis with 1311 healthy adults, and LHDL analysis with 711 healthy adults from the participants of the third phase (2006–2008) of the TLGS. Dietary intake of carotenoids was estimated using a validated 168-items semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire, at baseline. Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of HTC, HTG, LHDL, and HLDL were calculated in tertile categories of dietary carotenoids. Participants in the second tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake, had a 24% lower risk of HLDL (HR = 0.76, 95%CI: 0.60–0.96), and an 18% lower risk of HTC (HR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.66–0.98), compared to the participants in the first tertile. Also, participants in the second tertile of lycopene intake, compared to those in the first tertile had a 23% lower risk of HTG (HR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.63–0.97). There was no significant association between other dietary carotenoids and dyslipidemia. The results indicated beneficial effects of dietary β-cryptoxanthin and lycopene for lipid profile. However, more research is needed to clarify the specific mechanisms and to determine optimal nutritional sources and amounts of carotenoids for cardiovascular benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dyslipidemia, characterized by abnormal lipid levels in the blood, is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), which remain one of the leading causes of mortality globally1. This condition involves elevated levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TG), or reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)2. The estimated prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) (defined as serum TG ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1, hyperLDL-C (HLDL) (defined as serum LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL (3.36 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1, hypercholesterolemia (HTC) (defined as serum total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL (5.17 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1, and hypoHDL-C (LHDL) (defined as serum HDL-C < 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) for men and < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) for women, or using lipid-lowering drugs1 in the Iranian population, reported by a systematic review and meta-analysis study, was 46.0%, 35.5%, 41.6%, and 43.9%, respectively3.

Public health organizations globally have focused on reducing the prevalence of dyslipidemia and subsequently CVD incidence, by their modifiable risk factors including lifestyle factors and dietary intake2. Among the dietary factors, carotenoids, a class of plant pigments responsible for the red, yellow, and orange colors in fruits and vegetables, have drawn significant attention due to their potential cardio-protective properties4. Carotenoids, including α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin, possess potent antioxidant properties that can protect against oxidative stress, a key factor in lipid peroxidation and the progression of atherosclerosis5. Their role in lipid metabolism is also linked to their ability to modulate inflammatory responses and improve lipid profiles by influencing cholesterol absorption and regulating lipid transport6. For instance, lycopene has been shown to lower LDL-C levels7,8, while lutein and β-cryptoxanthin are associated with improvements in HDL-C concentrations and reduced risk of metabolic syndrome9. Furthermore, carotenoids may attenuate the oxidation of LDL-C particles, a critical step in the development of atherosclerotic plaques, thereby reducing CVD risk10. Despite the findings of the previous observational studies regarding the cardio-protective effects of dietary carotenoids, the existing evidence on the cardio-protective effects of dietary carotenoids remains inconclusive, and observational data—such as those from prospective cohort studies—are needed to clarify their associations with cardiovascular risk factors. These findings may help guide future mechanistic and interventional research to explore the underlying pathways and define optimal intake levels. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the prospective associations between dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin and the incidence of four types of dyslipidemia—hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hyperLDL-C, and hypoHDL-C—in a large adult cohort of Iranian population. By focusing on observational associations, our findings may help guide future mechanistic or interventional research in this field.

Material and methods

Study population

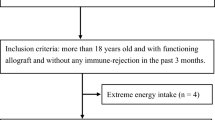

Data for the present prospective cohort study was obtained from the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS), an ongoing population-based study initiated in 1999 to assess risk factors for non-communicable diseases among residents of District 13 of Tehran, Iran. The TLGS enrolled 15,005 participants aged ≥ 3 years through multistage cluster random sampling and has conducted follow-up examinations approximately every three years11. For the present study, we included 10,091 adults aged 19 years and older who participated in the third phase of the TLGS (Fig. 1). Participants with incomplete dietary data (n = 7036), under or over-reports of energy intakes (< 800 kcal/d or > 4,200 kcal/d, respectively)12 (n = 170), missing data on anthropometric and biochemical measurements (n = 165), participants with a history of each of dyslipidemia conditions at baseline, including HTG (n = 1016), HLDL (n = 954), HTC (n = 1004), and LHDL (n = 1832), and those who were lost to follow-up in each study population, were excluded from the analyses. Finally, 1305 healthy adults remained for HTG analysis, 1326 healthy adults remained for HLDL analysis, 1311 healthy adults remained for HTC analysis, and 711 healthy adults remained for LHDL analysis. The eligible participants were followed up until the end of the study, in 2014–2017. Median follow-up periods for HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL analyses were 8.47 (inter-quartile range (IQR): 4.74–9.41), 8.46 (IQR: 4.77–9.44), 8.30 (IQR: 4.35–9.32) and 8.56 (IQR: 6.35–9.43) years from the baseline examination, respectively. It should be noted that for each dyslipidemia outcome, participants with that specific condition at baseline were excluded. As a result, the final sample sizes differ slightly across the four outcome groups.

Measurements

Interviewers were trained on questions in advance to collect demographic information such as age, gender, drug history, and smoking status (yes and no). Body weight, height, and waist circumference (WC) of participants were measured using a digital scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) and tape measure, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) is calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the square of height (m2). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured from the participants’ right arm using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer calibrated by the Iranian Institute of Standards and Industry13. Participants’ daily physical activity was assessed using the Modified Activity Questionnaire (MAQ) and expressed as metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-minutes/week)14. Physical activity scores of ≤ 600 MET-min/week were classified as low physical activity, while scores of > 600 MET-min/week were considered moderate to severe physical activity. The reliability and validity of the Persian version of the MAQ have been previously studied15.

Blood samples were taken from participants after an overnight fasting between 7:00 and 9:00 AM. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and lipid profile were measured using the enzymatic colorimetric method. FPG was measured using glucose oxidase, TG was measured using glycerol phosphate oxidase, and HDL-C was measured using phosphotungstic acid. All blood analyses were conducted at the research laboratory of the TLGS using Pars Azmoon kits (Pars Azmoon Inc., Tehran, Iran) and a Selectra 2 auto-analyzer (Vital Scientific, Spankeren, The Netherlands). The coefficients of variation (CV) for both inter- and intra-assay measurements during the baseline and follow-up phases were less than 5%.

Participants’ daily food intake was assessed using a 168-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). They were asked to report on the frequency (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly) and amounts (e.g., cups, tablespoons, and grams) of each food over the past 12 months. The reported frequency was converted to daily intake, and the measurement displayed on the home scale was changed to grams. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) food composition table was used to obtain the amount of energy per gram of each type of food, and the amount of each of carotenoids (including α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin). The validity of the FFQ has been previously evaluated16.

Definition of terms and outcomes

HTG or hypertriglyceridemia was defined as serum TG ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1.

HLDL or hyperLDL-C was defined as serum LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL (3.36 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1.

HTC or hypercholesterolemia was defined as serum total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL (5.17 mmol/L) or using lipid-lowering drugs1.

LHDL or hypoHDL-C was defined as serum HDL-C < 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) for men and < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) for women, or using lipid-lowering drugs1.

Statistical analyses

Mean (± SD) values and frequencies (%) of baseline characteristics of participants were compared according to the incidence of each outcome, using an independent t-test and chi-square test, respectively. The incidence of HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL outcomes over the follow-up periods were considered as dichotomous variables (yes/no) in the models. Dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin were categorized into tertiles. The first tertile of each category was considered as a reference.

Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between dietary carotenoids and the incidence of HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL. Person-years served as the underlying time metric for these models. The event date for HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL cases was determined as the time to the end of follow-up for censored cases or the time to experience an event, whichever came first. For individuals who were censored or lost to follow-up, the survival time was calculated as the interval between their first and last observation dates. The proportional hazard assumption of the multivariable Cox model was assessed using Schoenfeld’s global test of residuals. Potential confounding variables were initially assessed using univariate analysis (P < 0.20). In addition, known confounders identified from previous literature—including age, sex, smoking status, and physical activity—were included in the final models regardless of their univariate association, to ensure adequate adjustment and methodological rigor. Potential confounders, adjusted in the Cox models, include age (years), sex (men/women), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), physical activity level (low/high), current smoker (yes, no), total energy (kcal/d), total fat and fiber intakes (g/d).

To assess linear trends across tertiles of dietary carotenoid intake, the median value of each tertile was assigned to participants in that group and included as a continuous variable in the Cox regression models to calculate the P for trend.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (version 20; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with P-values < 0.05 being considered significant.

Results

Mean age (± SD) of the participants of HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL analysis populations were 38.07 ± 13.23, 38.16 ± 13.25, 37.80 ± 13.15, and 40.37 ± 14.45 years, respectively. From the total population of HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL analyses, 38.4%, 43.0%, 44.0% and 50.9% were men, respectively. Mean (± SD) dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin in HTG population were 942.7 (± 1013), 2925 (± 2568), 3858 (± 3074), 1733 (± 1405) and 271.3 (± 242.7) mcg/day. Mean (± SD) dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin in HLDL population were 910.6 (± 1008), 2829 (± 2443), 3906 (± 3159), 1714 (± 1258) and 265.8 (± 229.1) mcg/day. Also, mean (± SD) dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin in HTC population were 919.7 (± 1042), 2829 (± 2504), 3835 (± 3064), 1712 (± 1272) and 266.2 (± 234.4) mcg/day. Finally, mean (± SD) dietary intakes of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin in LHDL population were 876.2 (± 838.3), 2836 (± 2267), 3793 (± 2821), 1715 (± 1496) and 265.9 (± 212.4) mcg/day.

The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Compared to the participants who had no HTG events, participants with HTG tended to be older, more likely to be men and current smokers, had higher BMI, WC, and higher dietary intake of total saturated fats (SFA) (P for all < 0.05). Participants who had HLDL outcomes, compared to the participants who had no HLDL events, tended to be older, had higher BMI and WC, and had significantly higher daily intakes of total energy, total fat, total mono-unsaturated fats (MUFA) at baseline (P for all < 0.05). Participants who had HTC outcomes, compared with participants who had no HTC, tended to be older, had higher BMI and WC, and had significantly higher daily intakes of total energy, total fat, total MUFA at baseline (P for all < 0.05). Also, participants who had LHDL outcomes, compared with participants who had no LHDL, tended to be older, more likely to be men, had higher BMI and WC (P for all < 0.05). There was no significant difference in other characteristics of participants between the groups.

The HRs (95% CI) of dyslipidemia across tertile categories of α-carotene consumption are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for confounding variables, there were no significant associations between dietary α-carotene consumption and risk of HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL incidence (HR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.73–1.17; P for trend = 0.600 for HTG, HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.76–1.25; P for trend = 0.700 for HLDL, HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.77–1.21; P for trend = 0.934 for HTC, HR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.59–1.17; P for trend = 0.234 for LHDL).

The risks of dyslipidemia across tertile categories of dietary β-carotene are shown in Table 3. In the fully adjusted models, no significant association was observed between dietary β-carotene intake and risk of TG (HR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.73–1.18; P for trend = 0.608), HLDL (HR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.72–1.20; P for trend = 0.541), HTC (HR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.72–1.15; P for trend = 0.453) and LHDL (HR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.58–1.16; P for trend = 0.332).

Table 4 reported the HRs (95% CI) of dyslipidemia across tertile categories of β-cryptoxanthin. In the fully adjusted models, participants in the second tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake, who consumed 145.5 to 298.8 mcg/day of β-cryptoxanthin, had a 24% lower risk of HLDL, compared to the participants who consumed less than 145.5 mcg/day of β-cryptoxanthin. On the other hand, participants in the second tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake, who consumed 142.8 to 294.7 mcg/day of β-cryptoxanthin, had an 18% lower risk of HTC, compared to the participants who consumed less than 142.7 mcg/day of β-cryptoxanthin. However, the associations did not remain significant in the third tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake (P for trend = 0.526 for HLDL and P for trend = 0.128 for HTC). No significant association was observed between the third tertile of dietary β-cryptoxanthin intake and risk of TG (HR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.71–1.15; P for trend = 0.526), and LHDL (HR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.65–1.28; P for trend = 0.533).

The risks of dyslipidemia across tertile categories of dietary lutein are shown in Table 5. In the fully adjusted models, no significant association was observed between third tertile of dietary lutein intake and risk of TG (HR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.70–1.16; P for trend = 0.626), HLDL (HR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.73–1.23; P for trend = 0.553), HTC (HR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.72–1.16; P for trend = 0.471) and LHDL (HR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.83–1.71; P for trend = 0.178).

The HRs (95% CI) of dyslipidemia across tertile categories of lycopene consumption are shown in Table 6. In the fully adjusted models, participants in the second tertile of lycopene intake, who consumed 2190.4 to 4216.8 mcg/day of lycopene, had a 23% lower risk of HTG, compared to the participants who consumed less than 2190.3 mcg/day of lycopene, however, the association did not remain significant in the third tertile of lycopene intake (P for trend = 0.342). No significant association was observed between third tertile of dietary lycopene intake and risk of HLDL (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.85–1.39; P for trend = 0.516), HTC (HR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.77–1.21; P for trend = 0.744), and LHDL (HR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.67–1.26; P for trend = 0.679).

Discussion

In the present prospective cohort study, we investigated the longitudinal association between dietary carotenoids including α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin and the incidence of each condition of dyslipidemia (including HTG, HLDL, HTC and LHDL). We found potential protective effects of β-cryptoxanthin intake (142.8-294.7 mcg/day), as well as lycopene intake (2190.4-4216.8 mcg/day), from the habitual diet, in relation to risks of HLDL and HTC, and risk of HTG, during 8.56, 8.30, 8.47 years of follow-up, respectively.

The protective effects of β-cryptoxanthin against dyslipidemia we found in this study are in line with the results of the previous studies. Beta-cryptoxanthin is a carotenoid widely distributed in nature, found in fruits and vegetables such as citrus fruits, red peppers, squash, persimmons, and loquat and has many important functions in human health17. It has been claimed that β-cryptoxanthin has relatively high bioavailability from its common food sources, to the extent that some β-cryptoxanthin–rich foods might be equivalent to β-carotene–rich foods as sources of retinol18. B-cryptoxanthin is one of the few xanthophylls with pro-vitamin A activity because of producing retinal by cleavage in the middle of the molecule17. This carotenoid has recently gained attention for its risk-reducing effects on lifestyle-related diseases; it has been reported that dietary intake of β-cryptoxanthin might be associated with reduced risk of certain cancers and degenerative diseases18. Although a series of cell culture and rodent studies suggested that β-cryptoxanthin intake has an effect on bone health that is not duplicated by other carotenoids19, the few available human studies on the effects of β-cryptoxanthin or β-cryptoxanthin–rich foods on osteoporosis are not conclusive18. There is limited observational study investigated the association between dietary β-cryptoxanthin and risk of HLDL or HTC, separately from dyslipidemia or metabolic syndrome, however, our findings regarding the inverse association between dietary β-cryptoxanthin intake and risk of HLDL and HTC are align with existing literature. For instance, a cohort study investigated the longitudinal association between carotenoids and risk of developing metabolic syndrome and its components, reported a significantly lower risk of dyslipidemia in the highest tertiles of β-cryptoxanthin intake (HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.99)20. Also, β-cryptoxanthin might also play a role in cholesterol homeostasis by inducing mitochondrial sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1)21. In an animal study, feeding the mice with β-cryptoxanthin decreased the hepatic lipogenesis proteins acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, and the cholesterol synthesis genes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and HMG-CoA synthase 1, and increased the cholesterol catabolism gene cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase22. Collectively, the evidence from epidemiological and interventional studies has shown the potential of β-cryptoxanthin to prevent lifestyle-related diseases from different angles, not only as an antioxidant but also as a retinoid precursor.

Similarly, lycopene, a carotenoid predominantly found in tomatoes and tomato-based products, has garnered attention for its potential cardiovascular benefits23. Some recent review studies suggest that lycopene may exhibit lipid-lowering effects, primarily by modulating lipid metabolism and reducing oxidative stress24,25. It is hypothesized that lycopene enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes, leading to a decrease in LDL-C oxidation, which is a key factor in atherosclerosis development26. Furthermore, lycopene’s anti-inflammatory properties may contribute to improved endothelial function and lipid profiles27. Regarding the potential effects of lycopene intake on lipid profile, a number of previous clinical trials reported neutral effects of lycopene supplementation (with doses of 15–33 mg/day) on TG levels28,29,30, which are in contrast with our findings. Subsequently, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 clinical trial studies (n = 854) revealed no significant difference in TG level between the lycopene intake and control groups (SMD = -0.01 [95% CI: -0.15, 0.13], p = 0.88)31. To the best of our knowledge, the association between dietary lycopene intake and risk of HTG or levels of serum TG has not yet been investigated in the framework of a population-based prospective examination. Further large-scale cohort studies are needed to clarify the effects of dietary lycopene intake and its influences on lipid metabolism.

It should be noted that we did not see any significant association between dietary β-cryptoxanthin and lycopene intake and risk of HLDL, HTG and HTC in the third tertile of β-cryptoxanthin and lycopene intake, the non-significant trend in our study may be related to the other components of habitual diet of participants. For instance, participants in the third tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake, compared to the participants in the second tertile, had significant higher intakes of total energy (2542.18 ± 696.95 vs. 2299.13 ± 659.31 kcal/day), total fat (87.06 ± 34.01 vs. 80.89 ± 29.81 g/day), and saturated fat (28.79 ± 12.28 vs. 27.10 ± 10.87 g/day). Similarly, participants in the third tertile of lycopene intake had significant higher intake of total energy, total fat and saturated fats. Higher intake of total energy, total fat and saturated fat among the participants in the third tertile of β-cryptoxanthin intake, probably eliminated the protective effect of β-cryptoxanthin against HLDL and HTC. Therefore, it can be concluded that having a healthy and balanced diet is essential for the positive efficacy of carotenoids. Moreover, the pattern of significant associations observed only in the second tertile but not in the third may indicate a potential nonlinear (e.g., U-shaped) association between carotenoid intake and dyslipidemia risk. This warrants further investigation in future studies using non-linear modeling approaches to confirm and clarify this potential relationship.

We found no significant association between dietary intake of α-carotene, β-carotene and lutein and risk of dyslipidemia. Similar to the lycopene and β-cryptoxanthin, the association between dietary α-carotene, β-carotene and lutein intake and risk of dyslipidemia has not yet been investigated in the framework of a population-based prospective examination. Since circulating carotenoid levels are directly related to dietary carotenoids, previous studies that examined circulating carotenoids in relation to lipid profiles could be taken into account. However, such studies also have contradictory results. A previous cross-sectional study assessed the association between circulating carotenoids and lipid profile, and reported an inverse association between the total sum of carotenoids in plasma and serum TG concentrations32. On the other hand, a study reported no significant association between circulating β-carotene levels and serum TG, LDL-C and HDL-C levels33. The contradictories observed between the results may be explained by the differences in study designs, the habitual dietary patterns of participants and doses of the consumed carotenoids, genetic variations and other environmental factors.

The absence of significant associations for α-carotene, β-carotene, and lutein may be attributed to several factors. First, these carotenoids differ in their chemical structure and polarity compared to lycopene and β-cryptoxanthin, which may influence their bioavailability and absorption. For example, α-carotene and β-carotene require efficient micellar incorporation and are more sensitive to degradation during cooking and storage. Second, metabolic pathways vary among carotenoids; α- and β-carotene serve primarily as provitamin A carotenoids and may be metabolized differently than non-provitamin carotenoids like lycopene. Third, dietary sources of these carotenoids differ—α- and β-carotene are mainly found in dark green vegetables (e.g., spinach, kale), which are often consumed cooked, potentially reducing their bioavailability. In contrast, lycopene and β-cryptoxanthin are abundant in tomatoes and citrus fruits, which may be consumed raw or cooked in oil, enhancing absorption. Finally, regional dietary habits, including cooking methods and the fat content of meals, may affect carotenoid absorption and influence their biological impact. Further studies are needed to explore how these factors interact to influence lipid metabolism.

To the best of our knowledge, there is limited data regarding the longitudinal association between dietary intakes of individual carotenoids (separate from dietary habits or food groups) and risk of dyslipidemia (HTG, HTC, HLDL and LHDL) incidence. The prospective design of the present study, long follow-up period, representation of the general population, having acceptable validity and reliability of all assessment processes, and consideration of each of dietary carotenoid as an independent exposure, are strength points of the current study. However, the study has some limitations which should be taken into account. First, since adding many variables to adjust in the models would lead to instability of the models and could reduce the study power, we conducted univariate analysis to select the final confounders to adjust for, so the residual confounders’ effect was not considered. Second, as in any other prospective cohort study, changes in an individual’s diet and other metabolic risk factors during the study follow-up may lead to some degree of misclassification and biased estimated HRs. Third, dietary intake of carotenoids was assessed using FFQ; therefore, potential measurement errors are probable. Fourth, we did not have any information regarding the use of supplements such as omega-3, so the effects of them did not adjusted in the models. Fifth, we cannot generalize the results of the study to the other populations, due to the differences in culture and dietary factors unique to the Iranian population. Sixth, the analyses were conducted among healthy participants, so it cannot be generalize to the other populations. Finally, like any observational study, we cannot report any causation between dietary carotenoids intake and risk of incident dyslipidemia.

Conclusion

We found inverse associations between dietary β-cryptoxanthin intake (142.8-294.7 mcg/day), as well as lycopene intake (2190.4-4216.8 mcg/day), and risks of HLDL and HTC, and risk of HTG, respectively. However, due to the non-significant associations in the third tertiles of β-cryptoxanthin and lycopene intake, we suggest that having a healthy and balanced diet is essential for the positive efficacy of carotenoids. More research in other population with different dietary patterns is needed to clarify the specific mechanisms and to determine optimal dietary sources and amounts of carotenoids for cardiovascular benefits. Future studies should also consider the interactions between carotenoids and other dietary components, as well as individual health conditions, to better understand their role in dyslipidemia.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent

- MetS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acid

- TLGS:

-

Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Du, Z. & Qin, Y. Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease: Current knowledge, existing challenges, and new opportunities for management strategies. 12(1) (2023).

Hedayatnia, M. et al. Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease risk among the MASHAD study population. 19(1), 42 (2020).

Tabatabaei-Malazy, O. et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 5 (4), 373–393 (2014).

Voutilainen, S., Nurmi, T., Mursu, J. & Rissanen, T. H. Carotenoids and cardiovascular health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83 (6), 1265–1271 (2006).

Crupi, P. & Faienza, M. F. Overview of the potential beneficial effects of carotenoids on consumer health and well-being. 12(5) (2023).

Castellano, J. M., Espinosa, J. M. & Perona, J. S. Modulation of lipid transport and adipose tissue deposition by small lipophilic compounds. Front. cell. Dev. Biology. 8, 555359 (2020).

Przybylska, S. & Tokarczyk, G. Lycopene in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(4). (2022).

Tierney, A. C., Rumble, C. E., Billings, L. M. & George, E. S. Effect of dietary and supplemental lycopene on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 11 (6), 1453–1488 (2020).

Bouayed, J. & Vahid, F. Carotenoid pattern intake and relation to metabolic status, risk and syndrome, and its components - divergent findings from the ORISCAV-LUX-2 survey. Br. J. Nutr. 132 (1), 50–66 (2024).

Kiokias, S. & Proestos, C. Effect of natural food antioxidants against LDL and DNA. Oxid. Changes. 7(10) (2018).

Azizi, F., Zadeh-Vakili, A. & Takyar, M. Review of rationale, design, and initial findings: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 16 (4 Suppl), e84777–e (2018).

Satija, A., Yu, E., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Understanding nutritional epidemiology and its role in policy. Adv. Nutr. 6 (1), 5–18 (2015).

Askari, S. et al. Seasonal variations of blood pressure in adults: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Arch. Iran. Med. 17 (6), 441–443 (2014).

Chandrashekar Nooyi, S. et al. Metabolic equivalent and its associated factors in a rural community of Karnataka, India. Cureus 11 (6), e4974 (2019).

Momenan, A. A., Delshad, M., Mirmiran, P., Ghanbarian, A. & Azizi, F. Leisure time physical activity and its determinants among adults in Tehran: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2 (4), 243–251 (2011).

Mirmiran, P., Esfahani, F. H., Mehrabi, Y., Hedayati, M. & Azizi, F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health. Nutr. 13 (5), 654–662 (2010).

Nishino, A., Maoka, T. & Yasui, H. Preventive effects of β-cryptoxanthin, a potent antioxidant and provitamin A carotenoid, on lifestyle-related diseases-a central focus on its effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). 11(1) (2021).

Burri, B. J., La Frano, M. R. & Zhu, C. Absorption, metabolism, and functions of β-cryptoxanthin. Nutr. Rev. 74 (2), 69–82 (2016).

Yamaguchi, M. Role of carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin in bone homeostasis. J. Biomed. Sci. 19 (1), 36 (2012).

Sugiura, M., Nakamura, M., Ogawa, K., Ikoma, Y. & Yano, M. High serum carotenoids associated with lower risk for the metabolic syndrome and its components among Japanese subjects: Mikkabi cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 114 (10), 1674–1682 (2015).

Fu, H. et al. β-Cryptoxanthin uptake in THP-1 macrophages upregulates the CYP27A1 signaling pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58 (3), 425–436 (2014).

Lim, J. Y. et al. Dietary β-cryptoxanthin inhibits high-refined carbohydrate diet-induced fatty liver via differential protective mechanisms depending on carotenoid cleavage enzymes in male mice. J. Nutr. 149 (9), 1553–1564 (2019).

Khan, U. M., Sevindik, M. & Zarrabi, A. Lycopene: Food sources, biological activities, and human health benefits. 2021, 2713511 (2021).

Albrahim, T. Lycopene modulates oxidative stress and inflammation in hypercholesterolemic rats. Pharmaceuticals. 15(11) (2022).

Shafe, M. O., Gumede, N. M., Nyakudya, T. T. & Chivandi, E. Lycopene: A potent antioxidant with multiple health benefits. J. Nutr. Metabolism. 2024, 6252426 (2024).

Bin-Jumah, M. N. & Nadeem, M. S. Lycopene: A natural arsenal in the war against oxidative stress and cardiovascular diseases. 11(2) (2022).

Mozos, I. et al. Lycopene and vascular health. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 521 (2018).

Graydon, R. et al. Effect of lycopene supplementation on insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61 (10), 1196–1200 (2007).

Hininger, I. A. et al. No significant effects of lutein, lycopene or beta-carotene supplementation on biological markers of oxidative stress and LDL oxidizability in healthy adult subjects. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 20 (3), 232–238 (2001).

Xaplanteris, P. et al. Tomato paste supplementation improves endothelial dynamics and reduces plasma total oxidative status in healthy subjects. Nutr. Res. 32(5), 390–394 (2012).

Inoue, T., Yoshida, K., Sasaki, E., Aizawa, K. & Kamioka, H. Effects of lycopene intake on HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Food Sci. 86 (8), 3285–3302 (2021).

Marhuenda-Muñoz, M. et al. Circulating carotenoids are associated with favorable lipid and fatty acid profiles in an older population at high cardiovascular risk. Front. Nutr. 9, 967967 (2022).

Liu, S., Wu, Q., Wang, S. & He, Y. Causal associations between circulation β-carotene and cardiovascular disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Medicine 102 (48), e36432 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study participants and the field investigators of the TLGS for their cooperation and assistance in physical examinations, biochemical evaluation, and database management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G and S.M designed the study. Z.G analyzed the data. Z.G and P.M wrote the manuscript. F.A supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consents were obtained from all participants. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants adhered the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was approved by the ethics research council of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaeini, Z., Mirzaei, S., Mirmiran, P. et al. Dietary carotenoids and risk of dyslipidemia among adult participants of Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Sci Rep 15, 44110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27877-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27877-y