Abstract

To investigate the effects of the LEG structured curriculum model on the physical fitness of preschool children aged 3 to 6 years.A cluster random sampling method was employed to select a total of 221 preschool children as research subjects, comprising both experimental and control groups.The Chinese National Physical Fitness Standards (Preschool Section) were used to assess the physical fitness development levels of preschool children aged 3 to 6 years.The experimental results were statistically analyzed using independent samples t-tests and paired samples t-tests.After a 12-week experimental intervention, we found that: 1) The level of physical fitness development in young children showed an upward trend with increasing age.2) Both experimental and conventional curricula positively influence the physical development of children aged 3 to 6, but experimental curricula yield superior results compared to conventional ones.3) Gender differences exist in the physical fitness development of young children. Boys and girls in the experimental group showed greater improvements in physical fitness scores compared to the control group, without introducing new gender differences. Meanwhile, children in the control group exhibited more diverse gender differences than those in the experimental group.A 12-week intervention demonstrated that the LEG structured curriculum model significantly enhances physical fitness development in children aged 3 to 6 years without inducing new gender disparities. It is recommended that this course model be incorporated into the kindergarten outdoor activity curriculum system and promoted. Meanwhile, in the design and implementation of structured physical education programs, attention should not be limited to children’s age and gender differences, greater emphasis should be placed on the intrinsic connections and positive transfer between their fundamental motor skills, and systematically promote the development of children’s physical fitness.

Similar content being viewed by others

The ages of 3 to 6 represent a critical period for preschool children to master basic motor skills1 and develop physical fitness2.Physical fitness encompasses multiple physical and physiological components including cardiorespiratory endurance, strength, speed, reaction time, agility, balance, coordination, and flexibility3.It supports individuals’ physical activities, daily life, and work with vitality4,5.Research demonstrates that improving physical fitness holds significant importance for the health of preschool children, particularly in preventing obesity6. Moreover, even minor improvements in children’s physical fitness are accompanied by substantial enhancements in cardiovascular health7,8, which is crucial for the early prevention of cardiovascular events9. It is clear that physical fitness plays an essential role in promoting the healthy physical development of children.Various types of physical activities have been employed to intervene in preschool children’s physical fitness, such as sports games, rhythmic activities, sports exercises, fundamental movement activities, aerobic training, and integrated activities9,10.Research has found that improvements in children’s cardiorespiratory endurance, sit-ups, push-ups, and trunk strength are significantly associated with physical activities conducted within the school setting, but not with activities outside of school11.

Currently, among the various approaches to developing physical fitness in preschool children, different forms of physical exercise yield varying effects on physical fitness. It remains unclear which type of physical exercise is most effective in improving preschoolers’ physical fitness12. What is certain is that structured physical exercise programs are more effective than free play or unstructured physical activities in enhancing preschoolers’ physical fitness9,10,13.Although physical exercise and structured intervention programs have been widely applied to the physical fitness development of preschool children aged 3 to 6, few reports exist on the age and gender differences observed in young children participating in structured programs.

Robinson, L. E. et al. argue that children’s basic motor skills do not develop naturally, they require instruction, practice, and reinforcement within appropriate movement patterns to be acquired14,15,16,17.Research indicates that organized structured programs demonstrate significant effectiveness in improving and maintaining fine and gross motor skills18,19,20,21,22,23.Their curricula significantly outperform unstructured programs in promoting the development of fundamental movement skills24,25.These studies provide theoretical support for the design of structured curricula and confirm the association between structured curricula and the development of fundamental motor skills and physical fitness.

GOODWAY, J.D. et al. argue that the development of motor skills requires sufficient practice accumulation. Only when the practice time for a specific movement reaches 90 to 120 min can a profound“trace effect”be formed in the cerebral cortex, thereby enabling mastery of the skill26.This mechanism highlights the critical role of systematic learning and repetitive practice in motor skill development.

Indeed, the cerebellum is involved in motor learning27 and the striatum plays a key role in motor learning, in the long-term memorization of well-learned movements, in the acquisition of manual and visuomotor skills, and in the bimanual coordination skill28,29,30,31,32.Research indicates that there is a highly positive correlation between physical fitness and motor skills in young children33,34.Physical activity influence models mediated by motor skill proficiency represent an optimal mechanism for promoting physical fitness development in young children35.A study demonstrating that a specific basketball drill positively impacts hand dexterity validates the principle of training specificity, with effects extending beyond routine participation36.In summary, there is a correlation between children’s basic motor skills and physical fitness, which provides a basis for the experimental design.

Children aged 3 to 6 years old explore the external world through play during this period, which also marks the peak of play development. Different types of play vary in their ability to promote child development, and the selection of play formats is determined by the developmental goals of the child.Research indicates that aerobic games significantly enhance preschoolers’ physical abilities in horizontal jumping, speed, and endurance37, markedly improve lower-body explosive power and agility9, and substantially boost strength in 5- to 6-year-old boys and flexibility in girls38.

Although free play contributes to the accumulation of broad movement experiences, it falls short of meeting the requirements for systematic motor learning and cannot effectively support children in developing the interest and ability for lifelong participation in physical activities39,40.Therefore, integrating fundamental motor skill systems into game activities and constructing a structured curriculum model that combines learning objectives, practice structures, and game scenarios may be more conducive to enhancing young children’s physical fitness and motor skills.Research indicates that the “Teach, Practice diligently, Compete regularly” course model can effectively promote high-quality development in youth sports41, demonstrating significant effects on physical morphology, motor skills, and endurance fitness42.

Therefore, we designed the LEG curriculum model (L means Learning movements; E means Exercising skills; G means Game activities), optimized from the teaching, practice, and competition model in youth sports. Designed for children aged 3–6in socioeconomically underdeveloped regions, this structured curriculum aims to achieve the goals of “Enjoying fun, Enhancing physical fitness, Developing character, and Strengthening will power”.It promotes the simultaneous development of preschoolers’ fundamental movement skills, physical activity, and physical fitness through movement learning, skill practice, and game activities.It consists of five segments: warm-up activities, skill instruction, skill practice, game activities, and cool-down activities. It responds to the acquisition, practice, and consolidation of fundamental motor skills, demonstrating strong scientific validity and practical applicability43. However, its impact on the physical fitness of preschool children aged 3–6 years has yet to be substantiated.

Building upon this foundation, we drew upon the concepts of motor education in kindergarten zone-based physical activities44 and the Physical Fitness and Motor Ability or Sport Game (PMS) model45 to optimize the LEG curriculum model. This optimized model was then applied in the teaching practice of physical education demonstration classes at two rural kindergartens.Observations revealed that children aged 3–6 demonstrated strong interest and high participation levels, indicating the model’s suitability for preschool-aged children.Therefore, adopting the sports science research paradigm addresses the shortcomings of the PMS model in empirical studies of young children’s physical fitness, thereby strengthening the integrated practice of learning, practice, and play activities within structured curricula.

Research indicates that young children possess limited attention span, and intervention sessions that are either too long or too short may not yield optimal benefits16. From the perspective of intervention effectiveness, studies have found that sessions lasting 30–40 min, conducted at least twice weekly, with a total duration of 8–16 weeks, maximize intervention outcomes16,46.

Therefore, this study examines changes in preschoolers’ physical fitness resulting from a 12-week intervention program comprising 24 sessions, each lasting at least 30 min, totaling no less than 720 min.We hypothesize that the experimental group preschoolers will demonstrate significantly superior physical fitness at the end of the program compared to their pre-test levels and to the control group, with certain age and gender differences observed, to examine the impact of the LEG structured curriculum model on the physical fitness development of 3- to 6-year-old preschoolers.

Methods

Subjects

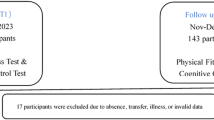

The participants in this study were drawn from a kindergarten located in an urban-rural fringe area of an economically underdeveloped region in western China.This study employed a voluntary participation approach and obtained informed consent from participants and their guardians. To minimize potential confounding factors affecting experimental outcomes, children who participated in extracurricular sports activities during the study period or were unsuitable for moderate-to-high intensity physical activities were excluded. The exclusion criteria resulted in 0 participants failing to meet study standards, 0 participants refusing to participate, and 0 participants excluded for other reasons, as shown in Fig. 1.This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chongqing Preschool Education College, the review date is October 8,2023,with the approval number 2,023,188.In accordance with the fundamental principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental protocol

We designed 24 sessions comprising 8 Mobility movements, 8 Object movements, and 8 Stability movements tailored to the physical and mental developmental characteristics of preschool children aged 3 to 6. These sessions were implemented to assess the impact of the experimental program on the physical fitness of children in this age group. For detailed information, please refer to the supplementary document P1-P3.

In the experiment, participants were required to complete a 12-week intervention program consisting of two sessions per week, each lasting at least 30 min, totaling no less than 720 min.The experimental group strictly followed the LEG curriculum model and content design steps: (1) Motor activation (10%); (2) Movement exploration and learning (20%); (3) Skill reinforcement practice (20%); (4) Game-based practice activities (40%); (5) Relaxation activities (10%). Each intervention session provided children with opportunities for movement learning, skill practice, and game activities, refer to curriculum cases E1-E3.The control group primarily utilized semi-structured and unstructured curricula. Semi-structured curricula combine teacher-led, goal-oriented instructional activities with student-selected, free-exploration physical activities, emphasizing children’s autonomy and skill development. Unstructured curriculum involves physical activities and games where children engage spontaneously, freely, and autonomously using teacher-provided materials. This form of physical activity lacks predetermined, uniform instructional objectives, fixed procedures, or mandatory guidance. It offers optional, self-directed experiences47 characterized by exploration, aiming to enhance communication and self-management skills48. For detailed examples, refer to curriculum cases C1-C3.

To evaluate the actual effectiveness of the experimental curriculum, the experimental program was implemented after being trained and assessed by members of the Early Childhood Physical Education and Health Research Center at Chongqing Preschool Education College.Additionally, considering that differences in teaching styles among instructors may influence experimental outcomes, each experimental course must meet the following six assessment criteria. The implementation process of each course must be recorded and analyzed via video documentation, as detailed in Table 1.

Measurement and evaluation

Children attend from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM Monday through Friday.The kindergarten provides all children with 40 min of morning exercise daily on a large playground, organized by age group and activity zone. Additionally, one outdoor zone-based play activity is conducted each day.All participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group using cluster randomization. The experimental group replaced outdoor regional play activities with experimental courses twice weekly for at least 30 min per session over 12 weeks, while the remaining three days featured routine outdoor regional play activities. Children in the control group experienced no changes.

Since the PREFIT Battery has been widely recognized and applied2,49,50,51, the modified PREFIT Battery based on the Fifth National Physical Fitness Standards for Children in China (Ages 3–6)52 was adopted as the assessment tool for this study. It comprehensively evaluates upper-body strength, lower-body strength, agility, flexibility, and balance in children aged 3–6 years, the test components are detailed in Table 2.All subjects underwent measurement and assessment of six physical fitness test indicators at the start of the intervention (0 W) and at its conclusion (12 W).In the pre-test phase, all participants underwent one adaptation test to familiarize themselves with the test content and procedures. After a one-day interval, baseline physical fitness was assessed for all participants. Following completion of the 12-week experimental intervention program, post-intervention PF was measured for all participants after a 48-hour interval.Since participants only underwent a 12-week microcycle intervention program, which is relatively short, no mid-term assessment was designed. Even though participants were in a rapid growth phase, this was unlikely to significantly impact the experimental outcomes, ensuring the validity of the results.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of physical fitness test indicators for children aged 3 to 6 years was conducted using SPSS 22.0 (Version 24.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD).Independent samples t-tests and paired samples t-tests were employed to analyze differences between pre- and post-intervention measurements. Comparative analyses were conducted on physical fitness among different groups, age cohorts, and genders. Test results indicate significant differences with “*” (P < 0.05) and double asterisks “**” (P < 0.01), no significant differences are denoted as “*” (P > 0.05).

Results

Basic information and characteristics of participants

This study recruited 221 participants, with 211 preschoolers completing physical fitness measurements and assessments at both 0 and 12 weeks. The experimental group comprised children aged 3–4 years (n = 31, 51.60% boys, 48.40% girls); 4–5 years (n = 31, 38.70% boys, 61.30% girls); 5–6 years old, n = 43, 55.80% boys, 44.20% girls), and the control group (3–4 years old, n = 32, 43.80% boys, 56.20% girls; 4–5 years old, n = 30, 50% boys, 50% girls; 5–6 years old, n = 44, 47.70% boys, 52.30% girls). Their basic characteristics followed a normal distribution, as shown in Table 3.

Comparison of physical fitness between experimental and control groups before intervention

Table 4 presents the results of an independent samples t-test comparing the baseline physical fitness levels of participants in the ExG and ConG groups prior to intervention (Week 0). The findings indicate that there was no significant difference in pre-intervention physical fitness levels between the experimental and control groups (p > 0.05).

Comparison of physical fitness in experimental group subjects from week 0 to week 12

Table 5 presents the results based on the paired samples t-test, reflecting changes in physical fitness among subjects in the experimental group from week 0 to week 12.We found that, except for 5- to 6-year-old children who showed no significant difference in the Walking the Balance Beam task (p > 0.05), all other participants exhibited significant differences in each physical fitness test indicator compared to pre-intervention levels (p < 0.01).

Comparison of physical fitness in control group subjects from week 0 to week 12

Table 6 presents the results based on the paired samples t-test, reflecting changes in physical fitness among control group subjects from Week 0 to Week 12.We found that, except for non-significant differences in grip strength among 3- to 4-year-olds and continuous jumping on both feet among 5- to 6-year-olds (p > 0.05), all other physical fitness test indicators showed significant differences compared to pre-intervention levels (p < 0.05).

Comparison of physical fitness score changes between the experimental and control groups from week 0 to week 12

Table 7 presents the results based on an independent samples t-test, reflecting the differences in physical fitness scores between the experimental and control groups after a 12-week intervention.We found that the variation scores for grip strength, standing long jump, continuous jumping on both feet, 15 m obstacle running, and walking the balance beam among 3- to 4-year-old children showed significant differences (p < 0.01), while the variation score for sitting forward bending showed no significant difference (p > 0.05).Significant differences were observed in the change scores for Grip strength、Sitting forward bending、15 m obstacle running、Walking the balance beam、Standing long jump、Continuous jumping on both feet among 4- to 5-year-old children (p < 0.05).Significant differences were observed in the change scores for Standing long jump、Sitting forward bending、15 m obstacle running、Continuous jumping on both feet among 5- to 6-year-old children (p < 0.05), no significant differences were found in the change scores for Grip strength and Walking the balance beam (p > 0.05).

Table 8 presents the results based on independent samples t-tests, reflecting the physical fitness status of male and female subjects in the experimental group at 0 weeks and 12 weeks.We found that gender differences among 3- to 4-year-old children were not significant at 0 weeks and 12 weeks (p > 0.05).At 0 weeks, 4- to 5-year-old boys demonstrated significantly greater grip strength than girls (p < 0.05), while girls exhibited significantly greater sitting forward bending than boys (p < 0.05). These gender differences became even more pronounced after 12 weeks (p < 0.01).At 0 weeks, 5-to 6-year-old boys demonstrated significantly greater grip strength than girls (p < 0.01), while girls showed significantly greater sitting forward bending ability than boys (p < 0.01). These differences persisted at 12 weeks.

Comparison of physical fitness between male and female subjects in the control group at 0 and 12 weeks

Table 9 presents the results based on independent samples t-tests, reflecting the physical fitness status of male and female subjects in the control group at 0 weeks and 12 weeks.We found that at 0 weeks, 3- to 4-year-old boys significantly outperformed girls in the 15 m obstacle run (p < 0.05); after 12 weeks, boys significantly outperformed girls in walking the balance beam (p < 0.05).At 0 weeks, boys in the 4–5 year-old group demonstrated significantly greater grip strength than girls (p < 0.05). At 12 weeks, boys exhibited significantly greater grip strength than girls (p < 0.05) and significantly greater standing long jump distance than girls (p < 0.01).At age 5–6, boys significantly outperformed girls in the standing long jump at Week 0 (p < 0.05), while girls significantly outperformed boys in the sitting forward bend (p < 0.01). Boys also significantly outperformed girls in the 15 m obstacle run and walking the balance beam (p < 0.05).After 12 weeks, boys demonstrated significantly superior grip strength compared to girls (p < 0.05). Boys also showed significantly superior standing long jump performance compared to girls (p < 0.01). Boys significantly outperformed girls in walking the balance beam (p < 0.05). Girls, however, significantly outperformed boys in sitting forward bending (p < 0.01).

Comparison of physical fitness score changes among male and female subjects in the experimental group after a 12-Week intervention

Table 10 presents the results based on independent samples t-tests, reflecting the changes in physical fitness scores among participants of different genders in the experimental group after a 12-week intervention.We found that only the 4- to 5-year-old children in the experimental group showed a significant difference in sitting forward bending (p < 0.05).

Comparison of physical fitness score changes among male and female subjects in the control group after a 12-Week intervention

Table 11 presents the results based on independent samples t-tests, reflecting the changes in physical fitness scores among participants of different genders in the control group after a 12-week intervention.We found significant differences in sitting forward bending among 3- to 4-year-old children (p < 0.05) and in 15 m obstacle running (p < 0.01). Additionally, significant differences were observed in 15 m obstacle running among 4- to 5-year-old children (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Kindergartens that design well-structured physical education programs and implement diverse recess activities can enhance children’s physical fitness and promote their healthy development53. Preschool teachers’ perceptions and understanding of physical activities54, along with the atmosphere they create for such activities55, play a crucial role in either facilitating or hindering children’s physical health development.This study employed cluster random sampling to implement a 12-week experimental intervention among preschool children aged 3 to 6 in kindergartens.Independent or paired t-tests were conducted to examine differences in characteristics among different groups, genders, and age groups of participants.After a 12-week experimental intervention, we found that both the experimental curriculum and the conventional curriculum had positive effects on the physical fitness development of children aged 3 to 6. However, the experimental curriculum demonstrated superior outcomes compared to the conventional curriculum, providing preliminary validation of the effectiveness of structured curricula across different ages and genders in early childhood education.

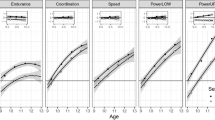

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, children’s physical fitness levels exhibit an upward trend with increasing age. This aligns with the perspective that basic motor capability naturally improves with growth and maturation in the absence of targeted interventions56, consistent with research findings indicating that all physical fitness test indicators increase with age in young children6.Table 5 also reveals that, except for the Walking the balance beam test among 5- to 6-year-old children where no significant difference was observed (p > 0.05), all other physical fitness test indicators showed significant differences among subjects (p < 0.01). This indicates that the post-test results of the experimental group significantly outperformed their pre-test results, consistent with the research hypothesis.Analysis suggests that this is because balance training exercises are more common in regional activities, whereas the Walking the balance beam test does not rely on motor skill transfer.Table 6 also reveals that, except for non-significant differences in grip strength among 3- to 4-year-olds and continuous jumping on both feet among 5- to 6-year-olds (p > 0.05), significant differences were observed in physical fitness test indicators across all other age groups (p < 0.05). This indicates that the regular curriculum is equally effective in enhancing physical fitness development in young children.In semi-structured and unstructured outdoor activities, running, jumping, and climbing can also promote the physical development of young children, aligning with the view that diverse physical activity programs promote the development of basic motor skills in young children57, while varied curricula foster the development of physical fitness58,59.

Table 7 reveals that after a 12-week intervention, the change in scores between the experimental and control groups for the 3- to 4-year-old children’s sitting forward bend was not significant (p > 0.05). This is because flexibility naturally declines with age, with male children showing a more pronounced decrease than female children, consistent with the findings of Zhu Weining60.There was no significant difference in grip strength and balance beam walking between 5- to 6-year-old children (p > 0.05). This is because upper limb strength and balance are frequently practiced through various regional activities, whereas the grip strength and balance beam walking tests do not rely on motor skill transfer or physical activity levels.The experimental results align with research findings indicating that diverse physical activity modules and structured exercise programs enhance preschool children’s physical fitness58,61, agility and flexibility58, and lower-body strength9.This indicates that the experimental curriculum aligns with the principle of training specificity. However, it contradicts the view that there are no significant differences in motor development between structured and unstructured curricula62,63.

As shown in Tables 8 and 9, gender differences emerged in the physical fitness performance of boys and girls between the experimental and control groups, with these differences gradually widening with age. This finding is consistent with the established view that gender differences in physical fitness development among young children become more pronounced with age under natural conditions6,60.Additionally, as age increases, boys demonstrate superior grip strength compared to girls, while girls exhibit superior sitting forward bending ability compared to boys. These differences remain significantly pronounced after 12 weeks, consistent with the view that young children’s physical fitness and health status exhibit inherent physiological and gender-related variations6,64,65.This indicates that neither structured nor unstructured curricula can alter young children’s innate developmental advantages. Curriculum design and implementation should respect these inherent physiological and gender differences.

As shown in Tables 10 and 11, the experimental group exhibited significant differences only in the sitting forward bending test for 4- to 5-year-old children (p < 0.05). The control group showed significant differences in the sitting forward bending test for 3- to 4-year-old children (p < 0.05) and in the 15 m obstacle running test (p < 0.01), while 4- to 5-year-old children in the control group demonstrated significant differences in the 15 m obstacle running test (p < 0.05).After 12 weeks, the change scores from the experimental and control groups showed that the experimental group demonstrated greater improvements in physical fitness for both boys and girls compared to the control group, without introducing new gender differences. Meanwhile, the control group exhibited a wider range of gender differences among the children than the experimental group.This indicates that the LEG structured curriculum not only enhances the physical fitness of both boys and girls more effectively but also does not introduce gender differences in early childhood physical development.

Observations indicate that because the experimental group’s participants engaged in a standardized, structured curriculum, children had few opportunities for independent choice. This structured curriculum model—incorporating movement exploration learning, skill reinforcement exercises, and game-based practice activities—addresses the physical fitness, fundamental motor skills, and physical activity development of preschool children aged 3 to 6 years across genders.This aligns with previous studies indicating that higher levels of physical activity correlate with better physical fitness scores66,67,68.In contrast, the control group, which primarily engaged in unstructured and semi-structured activities, provided children with greater autonomy in choosing both time and space during outdoor play. Their development of motor skills and physical fitness may have relied more heavily on personal interest, inevitably lacking the appropriate stimuli and skill transfer required for physical fitness assessments.We believe that the differences observed across various groups, ages, and genders of preschoolers in the LEG program compared to the free play control group can be attributed to its more structured curriculum design.This course model emphasizes teacher-led instruction, motor skills, practice frequency, and activity intensity, focusing on the“Skill instruction and practice”component. It not only enhances the development of fundamental motor skills but also provides specific stimuli for testing motor skills, thereby revealing individual differences within the group.

This study validated the positive impact of the LEG structured curriculum model on the physical fitness of preschool children aged 3 to 6 across different groups, ages, and genders, confirming its effectiveness.However, as a pilot study, this research suffers from limited statistical power due to restricted sample sizes across age groups, making it difficult to detect small effect sizes. This limitation particularly constrains the analysis of gender differences within age groups and necessitates further validation of conclusions regarding gender-specific characteristics.In the future, we will enhance efficacy analysis by expanding our sample size and conducting longitudinal tracking studies, while also delving deeper into the developmental benefits of this model across multiple dimensions, including children’s psychological, cognitive, and social development.

Conclusion

A 12-week intervention demonstrated that the LEG structured curriculum model significantly enhances physical fitness development in children aged 3 to 6 years without inducing new gender disparities. It is recommended that this curriculum model be incorporated into the outdoor activity curriculum system of kindergartens and promoted. Meanwhile, in the design and implementation of structured physical education programs, attention should not be limited to children’s age and gender differences, greater emphasis should be placed on the intrinsic connections and positive transfer between their fundamental motor skills, and systematically promote the development of children’s physical fitness.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Stodden, D. F. et al. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: an emergent Relationship. Quest. 60, 290–306 https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2008.10483582 (2008).

Ortega, F. B. et al. Systematic review and proposal of a field-based physical fitness-test battery in preschool children: the PREFIT battery. Sports Med. 45, 533–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0281-8 (2015).

Council of Europe Committee for the Development of Sport. Handbook for the EUROFIT Tests of Physical Fitness; Eurofit, C., Ed.;Italian National: Rome, Italy, (1998).

Cattuzzo, M. T. et al. Motor competence and health related physical fitness in youth: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.12.004 (2016).

Janssen, I. & Leblanc, A. G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7, 40 (2010).

Latorre-Román, P. et al. Physical fitness in preschool children: association with sex, age and weight status. Child. Care Health Dev. 43, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12404 (2017).

Kriemler, S. et al. J.Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren:cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 23, c785 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c785 (2010).

Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. et al. Effectiveness of a school-based physical activity intervention on adiposity, fitness and blood pressure: MOVI-KIDS study. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 279–285 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099655 (2020).

García-Hermoso Antonio; Alonso-Martinez Alicia M; Ramírez-Vélez Robinson; Izquierdo Mikel. Effects of exercise intervention on health-related physical fitness and blood pressure in preschool children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 50, 187–203 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01191-w (2020).

Wick, K., Leeger-Aschmann, C. S., Monn, N. D. & Radtke, T. Interventions to promote fundamental movement skills in childcare and kindergarten: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 47, 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0723-1 (2017).

Chen, W. et al. Health-related physical fitness and physical activity in elementary school students. BMC Public. Health 18, 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5107-45 (2018).

Wang, G. et al. The effect of physical exercise on fundamental movement skills and physical fitness among preschool children: study protocol for a Cluster-Randomized. Controlled Trial Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 6331 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph1910 (2022).

Weizhen, G. & Huan, W. Meta-analysis of the effects of physical activity intervention on physical fitness of 3-6-year-old children in China. China School Health 42, 1311–1317 + 1322.https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2021.09.009 (2021).

Robinson, L. E. Effect of a mastery climate motor program on object control skills and perceived physical competence in preschoolers. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2, 355–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599764 (2011).

Robinson, L. E. The relationship between perceived physical competence and fundamental motor skills in preschool children. Child Care Health Dev. 37, 589–596 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01187.x (2011).

Logan, S. W. et al. Getting the fundamentals of movement: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of motor skill interventions in children. Child. Care Health Dev. 38, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01307.x (2012).

Robinson, L. E. et al. Teaching practices that promote motor skills in early childhood settings. Early Childhood Educ. J. 40, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-011-0496-3 (2012).

Palma, M. S., Pereira, B. O. & Valentini, N. C. Guided play and free play in an enriched environment: impact on motor development.Motriz. Revista De Educacao Fisica. 20, 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-65742014000200007( (2014).

Robinson, L. E., Palmer, K. K. & Bub, K. L. Effect of the children’s health activity motor program on motor skills and self-regulation in head start preschoolers: an efficacy trial. Front. Public. Health 4, 173 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00173 (2016).

Robinson, L. E., Veldman, S. L., Palmer, K. K. & Okely, A. D. A ball skills intervention in preschoolers:the CHAMP randomized controlled trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 2234–2239. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001339 (2017).

Tortella, P., Haga, M., Lorås, H., Sigmundsson, H. & Fumagalli, G. Motor skill development in Italian pre-school children induced by structured activities in a specific playground. PLOS ONE. 11, e0160244 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160244 (2016).

Veldman, S. L., Jones, R. A. & Okely, A. D. Efficacy of gross motor skill interventions in young children: an updated systematic review. BMJ open. Sport Exerc. Med. 2, e000067 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000067 (2016).

Johnstone, A., Hughes, A. R., Martin, A. & Reilly, J. J. Utilising active play interventions to promote physical activity and improve fundamental movement skills in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health 18, 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5687-z (2018).

Abusleme-Allimant, R. et al. Effects of structured and unstructured physical activity on gross motor skills in preschool students to promote sustainability in the physical education classroom. Sustainability 15 (10167). https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310167 (2023).

Zhexiao, Z., Yaodong, G., Jianshe, L., Huanbin, Z. & Xiaoguang, Z. Design and empirical study of functional exercise program of preschoolers aged 3 ~ 6 years based on motor development.33, 187–198 https://doi.org/10.14036/j.cnki.cn11-4513.2021.02.010 (2021).

Goodway, J. D. & Branta, C. F. Influence of a motor skill intervention on fundamental motor skill development of disadvantaged preschool children.Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 4, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609062 (2003).

Park, I. S. et al. Experience-dependent plasticity of cerebellar vermis in basketball players. Cerebellum 8, 334–339 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-009-0100-1 (2009).

Debaere, F., Wenderoth, N., Sunaert, S., Van Hecke, P. & Swinnen, S. P. Changes in brain activation during the acquisition of a new bimanual coordination task. Neuropsychologia 42, 855–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.12.010 (2004).

Kraft, E. et al. The role of the basal ganglia in bimanual coordination. Brain Res. 1151, 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.142 (2007).

Floyer-Lea, A. & Matthews, P. M. Changing brain networks for visuomotor control with increased movement automaticity. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 2405–2412. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01092.2003 (2004).

Puttemans, V., Wenderoth, N. & Swinnen, S. P. Changes in brain activation during the acquisition of a multifrequency bimanual coordination task: from the cognitive stage to advanced levels of automaticity. J. Neurosci. 25, 4270–4278. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3866-04.2005( (2005).

Van Der Graaf, F. H., De Jong, B. M., Maguire, R. P., Meiners, L. C. & Leenders, K. L. Cerebral activation related to skills practice in a double serial reaction time task: striatal involvement in random-order sequence learning. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 20, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.02.003 (2004).

Zhang, L. & Li, H. W. Huan; Hu Shuiqing; Wang Zhengsong. Relationship between fundamental movement skills and physical fitness in children. Chin. JSch Health 41, 554–557.https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.04.020 (2020).

Wang, H. & Hu, S. Li Yichen; Zheng Yingdong. Canonical correlation of motor skills and physical fitness in preschool children. China Sport Sci. Technol. 55, 46–51. https://doi.org/10.16470/j.csst.2019018 (2019).

Wang Tingting.Research on the Development Characteristics and Mechanism of Physical Activity. Physical fitness and motor skills of preschoolers. Chinasport Sci. Technol. 58, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.16470/j.csst.2020068 (2022).

Amato, A. et al. Young basketball players have better manual dexterity performance than sportsmen and non-sportsmen of the same age: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 13, 20953. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48335-7 (2023).

Latorre-roman, P. A., Mora-lopez, D. & Garcia-pinillos, F. Effects of a physical activity programme in the school setting on physical fitness in preschool children. Child. Care Health Dev. 44, 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12550 (2018).

Gong Menglan. Research on the influence of physical games on the physical quality of the older children.Guangzhou. Inst. Phys. Educ. 04, 40. https://doi.org/10.27042/d.cnki.ggztc.2021.000077 (2022).

Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., Cliff, D. P., Barnett, L. M. & Okely, A. D. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents: review of associated health benefits. Sports Med. 40, 1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.2165/11536850-000000000-00000 (2010).

MacNamara, A., Collins, D. & Giblin, S. Just let them play? Deliberate Preparation as the most appropriate foundation for lifelong physical activity. Front. Psychol. 6 (1548). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01548 (2015).

Liu, J. Break through the key and promote the high quality development of school physical education in the New Era. J. TUS 37, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2022.03.001 (2022).

Shuliu Liao. A study on the effect of teaching, practicing and competing teaching model to improve junior high school students’ interest in physical education and endurance quality. Nan ling normaluniversity 04, 23 https://doi.org/10.27037/d.cnki.ggxsc.2023.000404 (2024).

Zuozheng Shi, X. The LEG program promotes the development of physical activity and fundamental movement skills in preschool children aged 3–6 years: a Delphi study. Front. Public. Health 13, 1521878–1521878 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1521878 (2025).

Daryl Siedentop. Sport Education: Quality PE Through Positives Port Experiences (Human Kinetics, 1994).

Cao Zhiyang. Research on the practice of PMS mode in kindergarten sports activities. Guizhou Normal Univ. 09, 75–79. https://doi.org/10.27048/d.cnki.ggzsu.2023.000675 (2023).

Donath, L. et al. Fundamental movement skills in preschoolers: a randomized controlled trial targeting object control proficiency. Child. Care Hlth dev. 41, 1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12232 (2015).

Theobald, M. et al. Children’s Perspect. play. Learn. Educational Pract. Educ. Sci. 5, 345–362 https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040345 (2015).

Kinder, C. J., Gaudreault, K. L. & Simonton, K. Structured and unstructured contexts in physical education: promoting activity, learning and motivation. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat Danc. 91, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2020.1768181 (2020).

Cadenas-Sanchez, C. et al. Assessing physical fitness in preschool children: Feasibility, reliability and practical recommendations for the PREFIT battery. J. Sci. Med. Sport 19, 910–915 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.02.003 (2016).

Mora-Gonzalez, J. et al. Estimating VO2max in children aged 5–6 years through the preschool-adapted 20-m shuttle-run test (PREFIT). Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 2295–2307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-017-3717-7 (2017).

Cadenas-Sanchez, C. et al. Physical fitness reference standards for preschool children:the PREFIT project. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 22, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.09.227 (2019).

China National Physical Fitness Monitoring Center. Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Workbook. 2023.08.

Eveline, V. C. et al. Preschooler’s physical activity levels and associations with lesson context, teacher’s behavior, and environment during preschool physical education. Early Child. Res. Q. 27, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.09.007 (2012).

Toussaint, N. et al. A preschool-based intervention for early childhood education and care (ECEC) teachers in promoting healthy eating and physical activity in toddlers: study protocol of the cluster randomized controlled trial PreSchool@HealthyWeight. BMC Public. Health. 19, 278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6611-x (2019).

Natale, R. A. et al. Role modeling as an early childhood obesity prevention strategy: effect of parents and teachers on preschool children’s healthy lifestyle habits. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 35, 378–387. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000074 (2014).

Behan, S., Belton, S., Peers, C., O’Connor, N. E. & Issartel, J. Moving well-being well: investigating the maturation of fundamental movement skill proficiency across sex in Irish children aged five to twelve. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2604–2612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1651144 (2019).

Wang Guangxu, Z., Shikun, S. & ShanLiu, Y. Effects of different physical exercise program interventions on fundamental movement skills of preschool children. J. Shanghai Univ. Phys. Educ. Sport. 47, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.16099/j.sus.2023.02.02.0001 (2023).

Popović, B. et al. Nine months of a structured multisport program improve physical fitness in preschool children: a quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 4935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144935 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. The effect of different physical exercise programs on physical fitness among preschool children: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20, 4254. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH20054254 (2023).

Zhu & Weining A study on the current physical quality of 3–6 year olds and its influencing factors. Fujian Normal Univ. 03, 121 https://doi.org/10.27019/d.cnki.gfjsu.2023.000510 (2023).

Liu, J., Gao, F. & Yuan, L. Effects of diversified sports activity module on physical fitness and mental health of 4–5-year-old preschoolers. Iran. J. Public. Health. 50, 1233–1240. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i6.6422 (2021).

Tortella, P., Haga, M., Lorås, H., Fumagalli, G. F. & Sigmundsson, H. Effects of free play and partly structured playground activity on motor competence in preschool children: A pragmatic comparison trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 7652. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19137652 (2022).

Mostafavi, R., Ziaee, V., Akbari, H. & Haji-Hosseini, S. T. Effects of SPARK physical education program on fundamental motor skills in 4–6 Year-Old children. Iran. J. Pediatr. 23, 216–219 Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23724186 (2023).

Zhenya, C. & Shuming, W. Relationship between physical Activity, sedentary behavior and physical health of preschool children. Xueqian Jiaoyu Yanjiu. 3, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2020.03.004 (2020).

Murrin, C. M. et al. Body mass index and height over three generations: evidence from the lifeways cross-generational cohort study. BMC Public. Health 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-81) (2012).

Serrano-Gallén, G., Arias-Palencia, N. M., González-Víllora, S., Gil-López, V. & Solera-Martínez, M. The relationship between physical activity, physical fitness and fatness in 3–6 years old boys and girls: A cross-sectional study. Transl Pediatr. 11, 1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.21037/TP-22-30 (2022).

Williams, H. G. et al. Motor skill performance and physical activity in preschool children. Obesity 16, 1421–1426. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.214 (2008).

Luo, X. et al. Association of physical activity and fitness with executive function among preschoolers. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 23, 100400. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJCHP.2023.100400 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the teachers and children of the Tiansheng Branch of Chongqing Preschool Education College Affiliated Kindergarten for their participation in the experimental research.

Funding

The work was supported by the 2025 project of the Science and Technology Research Program of the Chongqing Education Commission in China (No.KJZD-K202502902) ,and the Early Childhood Sports and Health Research Centre at Chongqing Preschool Education College (No. 2023KYPT-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. Conceptualization, Funding access, Writing–original draft, Writing – review & editing. XY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing–review & editing,management and supervision. X.L.Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing–review & editing. Z.L. ,Q.X.contributed ideas and helped with analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Yang, X., Long, X. et al. Effects of learning, exercise, and game curriculum model on the physical fitness of preschool children aged 3–6: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 44271 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27908-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27908-8