Abstract

Multi-cylinder synchronous control is critical for heavy machinery lifting operations, yet struggles to maintain precision under dynamic and asymmetric loads. Traditional strategies neglect the dynamic coupling between structural strain energy and hydraulic actuation, leading to energy accumulation and synchronization errors. This paper proposes a coordinated coupling control strategy based on dynamic strain energy balance. By decoupling lifting processes from synchronization control and integrating real-time strain energy feedback, the method dynamically compensates for deformation-induced deviations. A multi-physics co-simulation platform (MATLAB/AMESim-Adams) validates the approach, demonstrating significant improvements in synchronization accuracy and stability over conventional methods. Experimental results show the strategy reduces maximum synchronization errors by nearly half under variable loads while suppressing structural fatigue risks. This work advances high-precision multi-cylinder system design, with broader applications in heavy equipment requiring robust cooperative control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydraulic multi-cylinder synchronous control, as a critical branch of hydraulic servo systems, holds significant engineering value in aerospace equipment assembly, metallurgical tilting systems, and large-scale construction machinery for lifting/flipping operations involving high-inertia loads. High-precision synchronous control not only reduces torsional stress and friction losses between actuators but also significantly mitigates mechanical wear and torsional deformation, thereby enhancing system safety margins and extending equipment service life1. For example, during the “passenger-to-cargo” modification of aircraft, traditional lifting methods inevitably introduce positional errors between lifting points, altering stress states at modification areas and directly affecting retrofit quality2.

Current synchronization control strategies exhibit distinct hierarchical characteristics: under conventional conditions, engineering practices rely on error correction through structural stiffness. While such compensation mechanisms based on elastic deformation energy offer cost advantages, they struggle to meet high dynamic precision requirements due to structural stiffness thresholds. In precision control scenarios, strategies such as equal control, master-slave control, cross-coupling control, and adjacent cross-coupling control (ACCC) have been developed, combined with algorithms like fuzzy control, PID, fuzzy PID, sliding mode control, adaptive robust control, and neural network control to improve synchronization performance1,2,3. Recent academic research contributions in control algorithms have further advanced synchronization performance through “cascaded adaptive robust control” for high-order hydraulic systems4, “reinforcement learning-augmented adaptive robust control” for dynamic hyperparameter tuning5, “reinforcement learning-based position control” enhanced by deep neural networks6, “nonlinear model predictive cross-coupling with deep neural feedforward” for disturbance rejection7, “predictive neural network controllers” with PI comparisons in educational settings8, “double fuzzy recurrent neural network sliding mode control” for nonlinear mitigation9, and “neural network-based finite-time adaptive backstepping” for rapid convergence10. The design of multi-hydraulic-cylinder position synchronization control strategies comprises three components: (1) inner-loop tracking error controller design to ensure system tracking performance; (2) outer-loop synchronous compensation controller design to guarantee synchronization accuracy; and (3) synchronization control strategy design, where the coupling degree between subsystems is reflected in the strategy’s efficacy11.

Notably, research on multi-hydraulic-cylinder synchronization control draws from the theoretical framework of multi-motor synchronization technology. Jerković systematically reviews the evolution of multi-motor synchronization techniques, highlighting modern strategies such as ring coupling control, relative coupling control, adjacent tracking control, and coordinated control12. Shi validates the advantages of decoupling synchronization and tracking coefficients in multi-actuator collaborative operations13.

However, existing studies predominantly focus on displacement synchronization parameters while neglecting the dynamic coupling effects between strain energy of the lifted object and hydraulic systems. The absence of energy-dimensional interaction modeling leads to systemic deviations in traditional control strategies under asymmetric loads and dynamic disturbances. The strain energy accumulation-release cycle, induced by energy interactions, remains a key constraint on synchronization accuracy.

By reviewing the research and development of hydraulic synchronous control systems through Li’s article1, the novelty of this article lies in its exploration of the explicit linkage between strain energy dynamics and control compensation, a relationship that has not been previously investigated, unlike the well-established correlation between hydraulic cylinder displacement and control compensation. Breaking from traditional paradigms, this study innovatively constructs a hydraulic-mechanical coupling dynamic model and integrates a strain energy dynamic balance mechanism into the synchronization control framework. A MATLAB/AMESim-Adams multi-physics co-simulation platform is established to achieve closed-loop interaction validation of hydraulic actuation, structural deformation, and control algorithms: MATLAB/AMESim provides hydraulic cylinder displacement response data, while Adams calculates real-time shear forces at support points of the lifted object, feeding them as critical state variables into the control loop. This research paradigm not only reveals energy transfer laws in multi-cylinder collaborative operations but also fills theoretical gaps in energy-dimensional modeling, offering innovative solutions for the design of multi-actuator cooperative control systems in heavy equipment.

Simulation system construction

Multi-cylinder tilting dynamic model

This article established a four-cylinder-driven alloy steel plate tilting experimental platform (geometric specifications: \(10 \times 3 \times 0.05\) m; material parameters: density 4850 \(\textrm{kg} / \mathrm {m^3}\), Young’s modulus \(1.02 \times 10^{11}\ \textrm{N} / \mathrm {m^2}\), Poisson’s ratio 0.3). Four symmetrically arranged hydraulic cylinders (support spacing: 3 m) drive the system. As shown in Fig. 1, one side of the steel plate is connected to a fixed hinge support, while hydraulic cylinders provide hinged support at the midpoint. The dynamic behavior of hydraulic cylinder support points is precisely characterized using the Adams rigid-flexible coupling model. The steel plate undergoes finite element discretization for dynamic coupling analysis between structural deformation energy and hydraulic driving forces.

The tilting model (Fig. 1) illustrates the geometric configuration of the steel plate and hydraulic cylinders. The fixed hinge support constrains rotational motion, while hydraulic cylinders apply dynamic lifting forces. Asynchronous displacements at support points induce shear forces (\(F_{Si}\)), which directly correlate with strain energy accumulation in the steel plate. This model forms the basis for analyzing energy-dimensional coupling effects.

Sequential motion constraint mechanism for multi-stage hydraulic cylinders

For the dynamic analysis of the latter two stages of the four-stage hydraulic cylinders, the structure is shown in Fig. 2.

Sequential motion constraint equations are established based on piston chamber pressure balance principles:

Where: \(f_1\) is inter-cylinder frictional resistance (N), F is equivalent external load (N), \(D_i\) and \(d_i\) represent the piston diameter and piston rod diameter of the i-th stage cylinder (mm).

By eliminating pressure parameters \(p_1\), \(p_2\) from Eqs. (1) and (2), the geometric constraint condition for sequential motion of multi-stage cylinders is derived:

This condition requires a decreasing adjacent cylinder diameter ratio14, ensuring interference-free sequential extension/retraction of multi-stage cylinders in compliance with ISO 6020-2 design standards.

Key parameter settings

Hydraulic System Parameters: As shown in Table 1, the geometric parameters of the four-stage hydraulic cylinders strictly satisfy the sequential constraint condition in Eq. (3) (\(0.933> 0.895> 0.833 > 0.714\)), ensuring reliable sequential motion under complex conditions.

Load Characteristics: Simulate time-varying load conditions during dumping operations, where the external load F(t) linearly decays from \(10^5\ \textrm{N}\) (partial load \(\pm \ 33.3 \%\)) to \(10^4\ \textrm{N}\) .

Dynamic Response Parameters: Equivalent stiffness \(k = 10^6\ \mathrm {N/mm}\) (Deriving from the steel plate’s material properties), equivalent damping \(c = 10^5\ \mathrm {N/mm}\cdot \mathrm {s^{-1}}\) (Selected based on empirical damping ratios), maximum damping distance \(\delta _ {\max } = 0.001\ \textrm{mm}\) (Defined per ISO 6020-2 standards).

Multi-support cooperative deformation strain energy analysis

Theoretical framework for strain energy modeling

Based on the quasi-static loading assumption (kinetic energy contribution < 0.1%, thermal dissipation < 2%), a strain energy conservation equation is established in accordance with ISO 6892-1 material testing standards:

Where: \(F_{Si}\) is the deformation shear force at the i-th support point (positive downward), \(\Delta _i\) is the relative displacement of support point i (positive upward, defined using a right-hand coordinate system). This model transforms unbalanced external work entirely into internal strain energy of the steel plate, providing a theoretical foundation for energy-dimensional modeling.

The equivalent damping parameter c introduced in the “Key parameter settings” section (under Dynamic Response Parameters) partially addresses energy dissipation in the system. However, the strain energy model primarily operates under quasi-static assumptions, where dynamic effects (e.g., kinetic energy, transient damping losses) are mitigated through the dual-loop control architecture detailed in the “Dual-loop control mechanism based on strain energy dynamic balance” section, rather than being directly integrated into the strain energy formulation. This approach ensures computational tractability while maintaining robustness within the defined validity regime.

Multi-support coupling effect modeling

Model

As shown in Fig. 3, the flexible steel plate is subjected to three force systems: asymmetric load forces \(F_{Li}\) from AMESim, dynamic lifting forces \(F_i\) from hydraulic cylinders, and strain energy release shear forces \(F_{Si}\) fed back by Adams in real time.

Figure 3 depicts the three force systems acting on the steel plate: asymmetric loads (\(F_{Li}\)), hydraulic lifting forces (\(F_i\)), and strain energy-driven shear forces (\(F_{Si}\)). The interplay between these forces governs strain energy dynamics. For instance, when \(F_i\) lags behind \(F_{Li}\), the resultant shear forces (\(F_{Si}\)) drive energy accumulation.

This visualization clearly demonstrates that when hydraulic cylinder output forces \(F_i\) fail to dynamically compensate for load forces \(F_{Li}\), the modified load force becomes \(F_{Li}' = F_{Li} + F_{Si}\). This represents a significant advancement in simulation modeling, as it incorporates the shear force component calculated through Adams, thereby correcting partial load forces that were previously neglected in conventional models.

Assumptions and simplifications

To ensure computational tractability while preserving physical fidelity, the strain energy model incorporates the following key assumptions:

-

Quasi-static loading: Kinetic energy contributions are negligible (< 0.1%), allowing strain energy to dominate dynamic behavior.

-

Linear elastic material: The ASTM A36 steel plate obeys Hooke’s law, with stress-strain relationships remaining linear (yield strength \(\sigma _y \ge 355\ \textrm{MPa}\)).

-

Isotropic homogeneity: Material properties (Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio) are uniform across the steel plate.

-

Small deformations: Displacements (\(\Delta _i\)) are small relative to structural dimensions, avoiding geometric nonlinearities.

These simplifications enable the derivation of closed-form solutions for strain energy (Eq. (4)) while capturing essential energy transfer mechanisms.

Strain energy at a single support point is simplified as:

A four-support strain energy coupling matrix equation is constructed:

Where \(\Delta _{ij}\) represents the relative displacement of support point j with respect to i. The energy sign convention defines strain energy accumulation when \(\Delta _{ij}\) and \(F_{Si}\) share the same sign and release when they differ.

Subsequent Adams model validation confirms that strain energy magnitudes remain consistent regardless of the reference displacement (minimum or maximum), describing the same deformation state.

Simulation verification

Following NAFEMS benchmark requirements, a 1 m Q345 steel beam model is established in Adams (cross-section \(50 \times 50\ \textrm{mm}\), mesh size 5 mm). Support points are positioned at [0.05, 0.35, 0.65, 0.95] m, with forced displacements of [1, 0, 2, 3] mm. The simulation model (Fig. 4) shows:

Simulation Results: Shear force distribution at support points: \({F_s} = [40.24, - 91.73,62.82, - 11.32] \times {10^3}\) N ; calculated strain energy: \(V_\varepsilon ^{(i)} \approx 65.95\) J (relative deviation < 0.08%), verifying that the Adams rigid-flexible coupling dynamic model aligns with the hypothesis of using strain energy to reflect deformation.

Strain energy dynamic evolution and control mechanism

When asynchronous displacement differences exist among hydraulic cylinder outputs \(Y_i\), part of the mechanical work is converted into strain energy:

Where \(W_{ext}\) is the work done by hydraulic cylinders, \(W_{mesh}\) is effective lifting mechanical work, and \(V_\varepsilon\) is accumulated strain energy.

Following the strain energy sign convention, Fig. 5 quantitatively illustrates the impact of strain energy accumulation-release cycles on structural integrity:

Shear force characteristics and strain energy distribution at support points. (a) Deformation-induced shear force magnitude and direction, (b) Strain energy spatial distribution via coupling matrix (Eq. (6)).

Figure 5.(a) illustrates the magnitude and direction of induced shear forces caused by displacement differences among the four lifting points in the simulation validation example. Figure 5.(b) depicts the current strain energy distribution at these points under the defined energy sign convention (accumulation when \(\Delta _{ij}\) and \(F_{Si}\) share the same sign). This analysis lays the groundwork for the subsequent displacement compensation strategy, which addresses control adjustments based on incremental state variations.

The dynamic strain energy evolution process is shown in Fig. 6.

Coordinated Coupling Control strategy adjustment process:

Where \(W_{ext}^{'}\) is synchronous compensation work by hydraulic cylinders; \(\Delta L_i\) is relative deformation, characterized by shear force magnitude and direction via Eq. (10).

The compensation work increment for each hydraulic cylinder is expressed as:

The proportional relationship of shear force \(F_{Si}\) reflects the energy required for dynamic deformation recovery, making the compensation amount \({y_{ci}} \propto {F_{Si}}\), thereby providing theoretical guidance for control strategy design.

Dual-loop decoupling control architecture

Dual-loop control mechanism based on strain energy dynamic balance

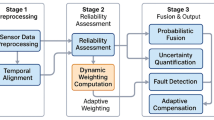

A dual-loop coordinated control architecture (Fig. 7) integrating strain energy dynamic balance principles is proposed to decouple tracking precision and synchronization stability:

In Fig. 7: \(y_{ref}\) is the position tracking target for four hydraulic cylinders; \(y_{ci}\) is the synchronization compensation output from the coordinated coupler; \(K_s\), \(K_t\) are synchronization and tracking coefficients; \(F_i(s)\) is the equivalent transfer function of the i-th position controller; \(F_{Li}^{'}\) is the modified load for the i-th hydraulic cylinder; \(G_{di} (s)\) is the disturbance transfer function; \(G_i (s)\) is the equivalent transfer function of the i-th hydraulic cylinder; \(\rho _i\) is displacement compensation weight for each cylinder; \(y_{ci}\) is displacement compensation.

Defining the block diagram functions as:

Additionally:

Inner Loop (Position Tracking): A proportional-integral controller achieves precise tracking of \(y_{ref}\) for individual cylinders.

Outer Loop (Energy Coordination): Based on strain energy weights \(\rho _i\), dynamic allocation of compensation \(y_{ci}\) suppresses strain energy accumulation at support points.

The position tracking transfer function \(G_{IOi} (s)\), relating \(y_{ref}\) and \(y_i\), is:

The load disturbance transfer function \(G_{LOi}\) (s), relating \(I_{Li}\) and \(y_i\), is:

The inter-cylinder coupling transfer function \(G_{jOi}\) (s), relating \(y_j\) and \(y_i\), is:

Where the coupling coefficient is defined as:\({K_{ci}} = (1 - {\rho _i}){K_s} + {\rho _i}{K_t}\).

Decoupling of tracking and synchronization errors

Synchronization error analysis

An error analysis model is established for three arbitrary cylinders (u, v, w). The tracking error transfer equation is derived via superposition:

Performing differential operations on \({y_u}(s) - {y_v}(s)\) and eliminating the coupling term \(y_w (s)\):

Substituting Eqs. (18), (19) and (20) into (22):

If \({F_u}(s){G_u}(s) = {F_v}(s){G_v}(s) = F(s)G(s)\), the synchronization error between hydraulic cylinders becomes:

According to Eqs. (24) and (25), tracking errors between hydraulic cylinders depend solely on \(K_s\), decreasing as \(K_s\) increases.

Tracking error analysis

Substituting Eqs. (22) and (25) into (21), \(y_u (s)\) is expressed as:

Further, the tracking error for hydraulic cylinders is:

Eq. (27) shows that synchronization error comprises three components. Since the latter two terms are higher-order compared to the first, the influence of \(K_s\) and \(\rho _i\) differences on tracking error is negligible. Thus, tracking error primarily depends on \(K_t\), decreasing as \(K_t\) increases.

Stability analysis

Lyapunov-based stability proof of the dual-loop control strategy

To rigorously validate the asymptotic stability of the proposed Coordinated Coupling Control (CCC) strategy, a Lyapunov stability analysis is performed. The system dynamics are formulated as follows:

Define the tracking error \(e_i = y_{\text {ref}} - y_i\) for the \(i\)-th hydraulic cylinder and the synchronization error \(e_{ij} = e_i - e_j\). The closed-loop dynamics can be expressed as:

where \(u_i = K_p e_i + K_i \int e_i \, dt + \sum _{j \ne i} \rho _{ij} K_s e_{ij}\) is the control input integrating PI terms and strain energy compensation, and \(d_i\) represents disturbances.

A composite Lyapunov function is constructed to simultaneously address tracking precision, synchronization stability, and strain energy dissipation:

where \(\lambda > 0\), \(\Delta _i\) is the relative displacement at the \(i\)-th support point, and \(k_{\varepsilon }\) is the structural stiffness.

Taking the time derivative of \(V\) and substituting the system dynamics yields:

where \(\eta > 0\) is a damping coefficient. The negative definiteness of \(\dot{V}\) confirms “asymptotic stability” of the closed-loop system.

This analysis demonstrates that: (1) The dual-loop architecture decouples tracking and synchronization errors. (2) Strain energy compensation (\(\rho _{ij} K_s e_{ij}\)) actively suppresses energy accumulation. (3) The system remains stable under partial and variable loads.

Derivation of coupled error dynamics and stability analysis

The dual-loop system (Fig. 7) is decomposed into state-space forms for the inner and outer loops. Let the state vector for the \(i\)-th hydraulic cylinder be:

The inner-loop PI controller dynamics are:

where \(u_i = K_t e_i + K_s \sum \rho _j (y_j - y_i)\) is the combined control input from tracking and synchronization terms. The system matrices \(\textbf{A}_i\), \(\textbf{B}_i\), and \(\textbf{B}_d\) are derived from Eqs. (18) and (20).

Define the tracking error \(e_i = y_{\text {ref}} - y_i\) and synchronization error \(e_{ij} = y_i - y_j\). From Eq. (27), the coupled error dynamics in the time domain are:

where \(\Delta F_{Li}'\) represents load disturbance variations. For the entire system, the error dynamics form a linear time-invariant (LTI) system:

where \(\textbf{M}\) is a Metzler matrix with diagonal entries \(-K_t - K_s \sum \rho _j\) and off-diagonal entries \(K_s \rho _j\). \(\textbf{D}\) bounds disturbances.

Theorem: The dual-loop system is asymptotically stable if \(K_t > 0\) and \(K_s > \frac{\max \rho _j}{\min \rho _j} \cdot \frac{\Vert \textbf{D} \Vert }{\lambda _{\min }(\textbf{Q})}\), where \(\textbf{Q}\) is a positive-definite matrix.

Proof: Choose the Lyapunov function \(V = \textbf{e}^T \textbf{P} \textbf{e}\), where \(\textbf{P}\) solves \(\textbf{M}^T \textbf{P} + \textbf{P} \textbf{M} = -\textbf{Q}\). The derivative is:

For \(\dot{V} < 0\), it suffices that:

Thus, errors \(\textbf{e}\) converge to a bounded region around zero.

Control strategy simulation validation

Simulation experiment design

Table 2 can guide researchers to reproduce the results.

The control algorithm flowcharts built in Simulink (MATLAB) are shown in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2 online, the AMESim hydraulic system diagram is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S3 online, and the Adams model diagram is provided in Supplementary Fig. S4 online.

The cross-platform data exchange architecture implements three critical signal (Shear force \(F_{Si}\), Hydraulic cylinder displacement \(y_i\) and Control signal \(u_i\)) pathways:

-

\(F_{Si}\): Adams \(\xrightarrow {\text {Co-simulation Manager}}\) MATLAB/Simulink \(\xrightarrow {\text {Co-simulation Manager}}\) AMESim (force feedback loop)

-

\(y_i\): AMESim \(\xrightarrow {\text {Co-simulation Manager}}\) MATLAB/Simulink \(\xrightarrow {\text {Co-simulation Manager}}\) Adams (motion coupling)

-

\(u_i\): MATLAB/Simulink \(\xrightarrow {\text {Co-simulation Manager}}\) AMESim (actuation interface)

A MATLAB/AMESim-Adams co-simulation platform is built to simulate the tilting process of a \(10 \times 3 \times 0.05\) m alloy steel plate:

-

Load Conditions: Initial loads for four hydraulic cylinders: \({F_{Li}} = [10, 12, 8, 6] \times {10^4}\) N, linearly decaying to \(10^4\) N over 10 s.

-

Control Parameters: Target displacement: 0.003 m; average cylinder extension speed: 3 \(\textrm{mm}/\textrm{s}\); simulation duration: 20 s.

-

Comparison Strategies: Coordinated Coupling Control (CCC) vs. Adjacent Cross-Coupling Control (ACCC).

Synchronization performance analysis

Figure 8 compares maximum synchronization errors under both strategies:

As shown in Fig. 8, the CCC strategy reduces the maximum synchronization error from 1.55 mm (ACCC) to 0.83 mm, achieving a 46.5% reduction.

The CCC strategy significantly improves synchronization accuracy through dynamic strain energy allocation, demonstrating stronger robustness under partial and variable loads.

Support point shear force response

Figure 9 compares dynamic shear force responses at support points.

ACCC uses displacement deviations between cylinders as compensation basis, exhibiting insensitivity to plate deformation, significant steady-state net synchronization errors, and pronounced shear force fluctuations. CCC minimizes synchronization errors and shear forces due to reduced plate deformation.

Strain energy dynamic, control signal and displacement response characteristics

Figures 10.(a) and (b) illustrates strain energy evolution under both strategies. For ACCC, strain energy release lags behind load changes, achieving energy balance only after 10 s. CCC completes strain energy release within 8 s via real-time compensation based on strain energy weights, effectively suppressing energy accumulation and accelerating release, thereby reducing structural fatigue risks.

Figures 10.(c) and (d) reveals dynamic characteristics of control signals. ACCC exhibits unidirectional signal attenuation with restricted valve spool adjustment. CCC enables bidirectional signal modulation, enhancing spool responsiveness.

Figures 10.(e) and (f) compares hydraulic cylinder displacement responses. Under partial loads during the first 10 s, without synchronization adjustment, the second hydraulic cylinder support becomes the lowest point, causing bending of the steel plate. For ACCC, the second support remains the lowest point under partial loads, failing to mitigate bending. In contrast, CCC detects plate deformation via real-time strain energy feedback from Adams simulations and adjusts support heights within 1 s, effectively reducing synchronization errors.

Implementation Challenges

While the co-simulation results validate the theoretical advantages of the Coordinated Coupling Control (CCC) strategy, practical implementation in physical systems faces several critical challenges. This section analyzes these challenges and proposes mitigation strategies to bridge the gap between simulation and real-world deployment.

Sensor latency and data synchronization

The strain energy feedback mechanism relies on real-time shear force measurements at support points. However, sensor latency (e.g., strain gauge response delays up to 10 ms) and asynchronous data acquisition across distributed subsystems may degrade synchronization accuracy. To address this:

-

Deterministic communication protocols: EtherCAT will be adopted for synchronized data sampling (1 kHz) across hydraulic, mechanical, and control subsystems.

-

Kalman filtering: A noise-reduction filter will refine strain energy estimates from shear force sensors, minimizing transient fluctuations.

-

Smith predictor: Compensate for feedback delays by integrating a predictive model of strain energy evolution into the control loop.

Actuator saturation and nonlinear dynamics

Hydraulic cylinder saturation under extreme loads (e.g., ± 33.3% partial loads) limits the compensation capability of proportional valves. Mitigation strategies include:

-

Dynamic clamping: Eq. (11) is modified to include spool displacement limits (± 90% of maximum stroke) and pressure relief thresholds (25 MPa) to prevent actuator overload.

-

Nonlinear friction compensation: Future work will integrate the LuGre friction model into the hydraulic cylinder dynamics to account for stick-slip effects.

-

Pressure-dependent viscosity correction: Adaptive fluid viscosity models will refine valve response under temperature variations.

Computational efficiency and embedded deployment

The co-simulation platform (MATLAB/AMESim-Adams) recorded a total simulation time of 20 s, with an actual computation time of 2.512 s (excluding real-time data exchange overhead). This yields a real-time factor (RTF) of 0.1256 (RTF = Computation Time / Simulated Time), demonstrating the algorithm’s efficiency in a non-optimized simulation environment. For embedded deployment, the dual-loop control law requires:

-

Loop frequency: 1 kHz (matching hydraulic dynamics).

-

Worst-case execution time (WCET): 0.85 ms per cycle (measured via Simulink Profiler), dominated by strain energy weight calculation (Eq. (15)) and PI control (Eq. (12)).

These metrics confirm feasibility for real-time execution on industrial PLCs (e.g., Beckhoff CX2040 with 1.4 GHz CPU) or DSPs (e.g., TI C2000 series). To further reduce latency:

-

Code optimization: Fixed-point arithmetic and lookup tables for strain energy weights (\(\rho _i\)).

-

Hardware acceleration: FPGA-based parallelization of matrix operations (Eq. (6)).

Future work will port the algorithm to an EtherCAT-enabled PLC (TwinCAT 3) for hardware-in-loop validation.

Deployment considerations

While the proposed Coordinated Coupling Control (CCC) strategy demonstrates significant improvements in simulation, its practical implementation in industrial environments necessitates addressing several critical challenges:

-

Sensor requirements and fusion: Real-time strain energy feedback relies on precise measurement of shear forces at support points. Industrial deployment would require high-frequency force sensors (e.g., piezoelectric load cells) or strain gauges integrated at hydraulic cylinder mounting points. Sensor placement must minimize mechanical interference while ensuring accurate force transduction. Additionally, sensor fusion techniques (e.g., Kalman filters) are essential to mitigate noise and synchronize data from heterogeneous sensors (position encoders, pressure transducers). The control algorithm’s dependency on real-time feedback also demands low-latency data acquisition systems with sampling rates \(\ge 1\) kHz to match the dynamics observed in simulations.

-

Actuator saturation and nonlinearities: Hydraulic cylinders in industrial settings operate within physical limits (e.g., maximum pressure, velocity, stroke). The CCC strategy must incorporate anti-windup compensators and saturation handling mechanisms to prevent integrator windup during abrupt load changes. Furthermore, nonlinearities such as friction hysteresis and valve dead zones, omitted in the current linear model, require empirical calibration or adaptive compensation to maintain synchronization accuracy.

-

Integration with industrial control systems: Compatibility with programmable logic controllers (PLCs) is crucial. The CCC’s dual-loop architecture could be implemented using IEC 61131-3-compliant function blocks, with synchronization coefficients (\(K_s, K_t\)) tunable via human-machine interfaces (HMIs). Communication protocols like OPC UA, as suggested in future work, would enable seamless integration with distributed control systems (DCS) while ensuring cybersecurity in networked environments.

-

Communication delays and real-time constraints: Distributed sensor-controller-actuator networks introduce latency, which can destabilize the control loop. Time-delay compensation methods, such as Smith predictors or model predictive control (MPC), should be integrated to account for transmission delays. Edge computing platforms could localize computational workloads, reducing reliance on centralized controllers and enhancing responsiveness.

-

Safety interlocks and fault tolerance: Industrial systems mandate fail-safe mechanisms. Redundant sensors, watchdog timers, and hardware-over-software priority interlocks must be implemented to detect cylinder malfunctions or communication failures. For instance, strain energy thresholds could trigger emergency stops if deformation exceeds safe limits. Additionally, graceful degradation protocols (e.g., load redistribution upon cylinder failure) would enhance system reliability.

-

Compatibility with standard hydraulic components: The four-stage cylinders modeled in this study adhere to ISO 6020-2 standards, ensuring compatibility with off-the-shelf industrial cylinders. However, variations in seal friction or manufacturing tolerances across vendors may necessitate parametric recalibration. Collaborative testing with industry partners (e.g., using digital twins) could validate the strategy’s adaptability to diverse hardware configurations.

-

Energy efficiency and thermal management: Prolonged operation under high loads may cause thermal drift in hydraulic fluids, affecting valve response and seal integrity. Integrating temperature feedback into the control loop and adopting variable displacement pumps could optimize energy consumption while mitigating thermal effects.

Addressing these deployment challenges requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining control theory, mechanical design, and industrial automation practices. Future experimental validation on physical testbeds, coupled with partnerships with heavy equipment manufacturers, will bridge the gap between simulation and real-world applicability. The CCC strategy’s reliance on strain energy dynamics positions it as a promising candidate for next-generation hydraulic systems, provided these practical considerations are systematically resolved.

Rationale for omitting physical testing

The current study focuses on establishing a theoretical framework and validating the proposed control strategy through a multi-physics co-simulation platform. While experimental or hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing is critical for practical validation, the following constraints influenced the prioritization of simulation-based analysis:

-

Complexity of heavy machinery prototyping: Physical replication of the four-cylinder tilting system (e.g., \(10 \times 3 \times 0.05\) m alloy steel plate) requires significant industrial-grade infrastructure, which is resource-intensive in terms of cost and time.

-

Safety Considerations: Asymmetric loads and dynamic disturbances in real-world scenarios pose risks of structural damage during initial testing. Co-simulation allows for rigorous safety evaluations before physical implementation.

-

Focus on theoretical innovation: The primary objective was to introduce strain energy dynamics into synchronization control, necessitating extensive parametric studies and iterative algorithm refinement, which are more efficiently conducted in a virtual environment.

Conclusions

This study innovatively constructs a strain energy-driven multi-cylinder coordinated coupling strategy, achieving the following breakthroughs:

Control Strategy Innovation: The proposed dual-loop Coordinated Coupling Control (CCC) strategy, based on strain energy weight allocation, achieves dynamic balance between energy accumulation and release through hydraulic-mechanical coupling modeling. Compared to ACCC, maximum synchronization error is reduced by 46.5%.

Multi-Physics Modeling Advancement: The MATLAB/AMESim-Adams co-simulation platform reveals dynamic coupling laws among hydraulic driving forces, structural deformation energy, and control signals.

Future work and outlook

Future work

Advanced material and nonlinear modeling: The current quasi-static linear elastic model will be extended to incorporate plasticity and damage effects. A Chaboche nonlinear hardening constitutive model will be integrated with strain energy dynamics to characterize fatigue accumulation under cyclic loads. This will enable predictive maintenance frameworks by correlating strain energy dissipation with structural health metrics.

Edge computing and industrial integration: The CCC strategy will be deployed on edge computing platforms using OPC UA communication protocols for interoperability with industrial IoT ecosystems. Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms will optimize real-time compensation by solving constrained quadratic programming problems on embedded GPUs, balancing synchronization accuracy with computational latency.

Digital twins and AI-driven enhancements: A digital twin framework will virtualize the hydraulic-mechanical coupling dynamics, enabling hardware-in-loop validation and proactive strain energy compensation. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) agents will train on twin-generated data to develop Long-term Adaptive Tracking Models (LATM), predicting load variations and pre-adjusting control parameters.

Advanced control algorithm integration: Incorporating advanced control algorithms–such as adaptive sliding mode control, distributed model predictive control, and hybrid reinforcement learning architectures–to further optimize synchronization performance under complex nonlinearities and disturbances.

Experimental Validation and Statistical Robustness: Conducting physics experiments on a scaled industrial testbed, incorporating statistical methods (e.g., repeated trials under variable loads ±50%, environmental noise, and temperature fluctuations) to rigorously quantify synchronization accuracy, strain energy dissipation rates, and structural fatigue metrics. These experiments will validate the robustness of the strain-energy-based approach and refine its practical applicability.

Broader impact

By integrating advanced modeling, edge computing, and digital twins, this outlook positions the CCC strategy as a cornerstone for intelligent heavy machinery. Applications span automated construction, precision aerospace assembly, and renewable energy infrastructure, fostering safer, greener, and more adaptive industrial systems.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Li, R. et al. Review of research and development of hydraulic synchronous control system. Processes 11, 981 (2023).

Zhu, S. Research on cooperative hydraulic control for aircraft modification lifting. Master’s thesis, Civil Aviation University of China (2023).

Cheng, S. & Zhang, Q. New device for large structure module docking and multi-cylinder synchronous control. ChinaMech. Eng. 29, 1214 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Cascade control method for hydraulic secondary regulation drive system based on adaptive robust control. ISA Trans. 156, 479–489 (2025).

He, J. et al. Control strategy of hydraulic servo control systems based on the integration of soft actor-critic and adaptive robust control. IEEE Access 12, 63629–63643 (2024).

Kang, H., Kim, J. T., Park, S. & Cho, J. Reinforcement learning based position control of 1-dof rotational hydraulic actuator. In 2024 24th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), 17–18 (IEEE, 2024).

Li, D. et al. Nonlinear model predictive control—cross-coupling control with deep neural network feedforward for multi-hydraulic system synchronization control. ISA Trans. 150, 30–43 (2024).

Duvanov, E., Batishchev, R., Pashchenko, A., Fedyanin, T. & Meleshkin, N. Applying of predictive neural network controllers in a hydraulic control object. In 2024 4th International Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning in Higher Education (TELE), 422–427 (IEEE, 2024).

Chai, L., Luan, H. & Liu, Z. A hydraulic transmission system based on double fuzzy recurrent neural network sliding mode control. In 2023 9th International Conference on Fluid Power and Mechatronics (FPM), 1–8 (IEEE, 2023).

Niu, S., Wang, J., Zhao, J. & Shen, W. Neural network-based finite-time command-filtered adaptive backstepping control of electro-hydraulic servo system with a three-stage valve. ISA Trans. 144, 419–435 (2024).

Meng, Y. Research on position synchronous control strategy of multiple hydraulic cylinders. Master’s thesis, Yanshan University (2023).

Jerković Štil, V., Varga, T., Benšić, T. & Barukčić, M. A survey of fuzzy algorithms used in multi-motor systems control. Electronics 9, 1788 (2020).

Shi, T., Liu, H., Geng, Q. & Xia, C. Improved relative coupling control structure for multi-motor speed synchronous driving system. IET Electr. Power Appl. 10, 451–457 (2016).

Xie, J., Luo, Z., Tian, G. & Li, L. Modeling and simulation of multi-stage hydraulic cylinder based on amesim. Mach. ToolHydraul. 38, 126–129 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. conceived the experiment, X.Y. and W.B. conducted the experiment, X.J., S.Q. and Z.P. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, Y., Wang, B., Xu, J. et al. Research on multi-cylinder coordinated coupling synchronous control strategy based on strain energy. Sci Rep 15, 44277 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27946-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27946-2