Abstract

The properties of laminated soft-hard composite rock masses are significantly influenced by the thickness ratio of the soft and hard rock layers, due to their inherent heterogeneity and anisotropy. This study investigates the mechanical properties and mesoscopic damage of soft-hard composite rock mass with varying layer thickness ratios. Soft-hard composite rock samples with different thickness ratios were prepared, and uniaxial compression experiments were conducted using an acoustic emission (AE) system to examine the mechanical behaviour and failure characteristics of these composite rock masses. The key findings are as follows: (1) Mechanical parameters exhibit a linear decline with increasing soft rock thickness. When the soft rock thickness ratio increased from 10% to 90%, the peak strength of the composite rock mass decreased by 62.8%, from 45.12 MPa to 16.8 MPa; the elastic modulus decreased by 36.8%, from 9.77 GPa to 6.17 GPa. (2) The number of surface cracks gradually decreases as the proportion of soft rock thickness increases, while oblique cracks progressively increase. The failure mode transitions from splitting failure to shear failure. When soft rock thickness is low, splitting failure dominated by hard rock predominates. As soft rock thickness increases, the failure mode shifts to predominantly shear failure, with the duration of the plastic stage extending from 200 s to 600 s. (3) Based on the law of conservation of energy, the energy evolution of the rock under unidirectional loading was analysed. The relationship between the energy evolution of soft-hard composite rock mass and the layer thickness ratio was constructed by considering the elastic constant and peak strength of the soft-hard composite rock mass. (4) A damage constitutive model was proposed based on Weibull distribution theory. This model accounts for the influence of the layer thickness ratio on macroscopic deformation localization, considering microscopic rupture damage. It provides a better fit for the stress–strain curve of soft-hard composite rock masses under unidirectional loading, offering an effective characterization of their mechanical behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Layered rock masses are widely distributed in nature. Due to various geological processes, the mechanical properties of layered soft-hard composite rock masses differ significantly from those of single rock types and exhibit characteristics of heterogeneity and anisotropy. Given the influence of these rock masses on engineering construction, understanding their mechanical properties has become a primary focus in the field of geotechnical engineering.

Because of the randomness and variability of natural rock samples, conducting comparative tests is challenging. To address this limitation, some researchers have cut and polished natural rocks into regular specimens of certain sizes and shapes, and utilized artificial binders as bonding layers to create soft and hard-medium composite masses with varying interlayer materials1,2. In addition, with the rapid advancement of 3D printing technology, some scholars have utilized specific printing materials to directly produce soft-hard composite rock masses. This approach has enabled precise control over the geometric shape, size, and internal structure of the specimens, including the distribution of fractures and joints, thereby effectively simulating the complex structural characteristics of rocks3,4,5,6,7. However, the most cost-effective methods, based on the principles of similarity theory, combine aggregates such as quartz sand and river sand with binding materials like cement, kaolin and gypsum to produce rock-like samples8,9. Experimental results have confirmed that these rock-like samples effectively replicate the properties of natural rocks.

Laboratory tests have allowed researchers to intuitively assess the mechanical properties of these rock-like samples, investigate the crack-opening effect, and develop a crack-opening model10. For soft-hard composite rock masses, initial damage plays a critical role in the development of secondary cracks. The extent of initial damage directly influences the number and distribution of secondary cracks, with a higher degree of initial damage resulting in more extensive secondary cracking and a notable increase in shear cracks. Additionally, as crack inclination increases or crack opening decreases, both the uniaxial compressive strength and peak strain of rock samples tend to rise11,12,13.

To capture the specific processes involved in the internal failure of a sample during loading, scholars have introduced Acoustic Emission (AE) signal monitoring systems. These systems provide critical data on crack development, deformation differences, and energy evolution within specimens14,15,16,17,18,19. LIN H et al.20 conducted uniaxial compression experiments on composite rock masses with three parallel joints using AE technology. Their findings revealed that an increase in joint density within the hard layer accentuated the rock mass’s brittleness. Similarly, Jianping et al.21 examined the AE characteristics and spatial distribution of coal-rock combinations during loading and failure. They analyzed crack evolution patterns and proposed pre-peak crack closure, crack opening, and post-peak crack evolution models of coal-rock combinations.

The deformation and destruction of rock is the result of internal damage accumulation, in order to study the emergence, expansion and interaction of microfracture within the rock. Scholars based on the theory of damage mechanics, through the introduction of damage variables, quantitatively describes the change of the damage degree of the rock in the loading process, and closely linked to the macro-mechanical properties, and effectively establish the damage constitutive model of the soft and hard composite rock masses22,23,24,25. Based on the theoretical framework of continuum mechanics, a model is constructed by introducing damage variables. Zhang et al.26 formulated a constitutive damage equation using continuous medium theory and derived model parameters based on characteristic rock properties. Wang et al.27 proposed a damage evolution model and constitutive equation for jointed rock bodies, accounting for the combined effects of the rock structure and load coupling. The theory of elastic mechanics is the basis of the rock constitutive model, which provides the stress-strain relationship of the rock in the undamaged state, and the change of parameters such as elastic modulus can reflect the degree of damage to the internal microstructure of the rock28,29,30,31. Nowadays, probabilistic statistical theory is increasingly applied in the study of rock damage constitutive models. This approach treats rock as composed of numerous randomly distributed micro-elements and micro-fractures, defining damage through the statistical distribution of micro-element strength. Consequently, it enables more accurate prediction of damage evolution patterns in rock under varying stress levels32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Some scholars even compared the Weibull distribution model with other distribution models, and found that the Weibull distribution can better reflect the strength and elastic modulus distribution of rocks under compression conditions, and more accurately establish the damage constitutive model39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

In summary, the current research on composite rock masses primarily focuses on the mechanical properties of soft-hard rock masses with equal thickness. However, key aspects such as the effect of variations in the thickness ratio between soft and hard rock layers and the complete energy evolution process remain underexplored. Additionally, studies on the mesoscopic constitutive models for layered soft-hard composite rock masses are limited and require further refinement.

To address these gaps, this study prepared rock-like samples of layered soft-hard composite rock masses. Through uniaxial compression experiments combined with AE system monitoring, the mechanical properties and energy evolution law of samples with varying soft and hard layer thickness ratios were analyzed. A damage constitutive model was then established based on the principle of mesoscopic rupture damage while considering the influence of the layer thickness ratio on macroscopic deformation localisation.

Test methods

Sample Preparation

Building on previous research47,48, this study selected M42.5 ordinary Portland cement and building gypsum as binding agents. To enhance sample compactness, two types of quartz sand with particle sizes of 100 and 200 mesh were used as aggregates.

Following the International Society of Rock Mechanics (ISRM) standards, the samples were processed into standard cylindrical rock specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm. Using the Platts classification method and its rock firmness coefficient, target strength values and proportioning schemes were determined, as shown in Table 1.

The samples of the uniaxial compression experiments were standard cylinder samples, which were divided into 10 parts along the height direction, and the thickness of the soft rock layer was increased in turn to form 11 groups of samples, as shown in Fig. 1.

After collection, the samples were classified, labelled, and stored in an indoor environment (Fig. 2).

Sample screening

To ensure the uniformity of the rock-like samples, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy spectrum analysis (energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy; EDS) were employed to observe the mesoscopic characteristics of randomly selected samples from the study area.

(1) Sample treatment:

As concrete itself is non-conductive and possesses a porous internal structure, direct observation readily leads to charge accumulation that obscures the true morphology. The samples underwent pretreatment to improve the accuracy of SEM observations. The detailed steps of the sample preparation process are depicted in Fig. 3.

(2) Test equipment:

The detailed characteristics of the sample, including pore distribution and the spatial arrangement of cement, gypsum, and other components were observed using a JSM-7610 field emission scanning electron microscope.

In conjunction with SEM observations, an energy spectrum analyser was employed to determine the elemental distribution within selected windows of the samples. Figure 4 shows the equipment used in this experiment.

(3) Sample testing:

To gain detailed insights into the pore structure and component distributions within the samples, the magnification was adjusted for specific regions of the soft and hard rock specimens. High-magnification observations captured these features, as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6.

SEM analysis revealed the presence of small pores within the sample. However, the hydration products closely adhered to the surface of the sand particles, indicating strong bonding between the components. Additionally, energy spectrum analysis provided statistical data on the element distribution within the observation window. The results demonstrated that different elements were uniformly distributed across the sample. Figure 7 presents the distribution characteristics of various elements, including the distribution of Ca in both the soft and hard rock samples.

The samples were initially screened using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to eliminate those with significant variability. The nuclear magnetic resonance results for all the samples in the 3-X group (with a soft rock thickness of 30 mm) are presented in Fig. 8.

There is no universally accepted standard for analysing the pore size using NMR. Scholars49,50,51,52,53 classified rock pores into micropores (< 1 μm), small pores (1–100 μm), medium pores (100–1000 μm) and macropores (> 100 μm). As shown in Fig. 8, the majority of pores in the sample were found to be micropores. To minimize the impact of sample variability on the tests, samples 3–4 and 3–8 were excluded from further analysis. The remaining samples underwent ultrasonic testing and a secondary screening. This process was repeated for the other sample groups.

The NMR-preliminarily screened samples were then subjected to ultrasonic testing to assess their internal damage. Three samples from each group were retained, ensuring that the difference in longitudinal wave velocity did not exceed 5%. The screening results are summarized in Table 2.

The strength of joint surfaces within composite rock masses significantly influences the properties of composite specimens. Therefore, variable-angle shear tests were conducted to determine the characteristics of these joint surfaces. To assess joint strength, composite specimens were prepared as 100 mm-cubed cubes with a 1:1 ratio of soft to hard rock layers. A variable-angle shear tester was employed to measure the shear strength parameters at the interface between the soft and hard rock layers. Variable-angle shear tests were conducted at three angles—35°, 45°, and 55°—to assess joint strength, with at least three specimens tested per angle. The variable-angle shear test setup is illustrated in Fig. 9.

Calculations indicate that the cohesion of the joint surface is 0.896 MPa, with an internal friction angle of 41.67°. According to the Engineering Rock Mass Classification Standard (GB50218-2014), where the cohesion of a joint surface exceeds 0.22 MPa and the internal friction angle exceeds 37°, the interface between soft and hard rock strata may be classified as a strongly jointed surface.

Test equipment

Uniaxial loading device

Loading device and conditions

The uniaxial compression tests were conducted using a CRIMS-DNS200 electronic universal testing machine. The loading was controlled via displacement, at a rate of 0.05 mm/min. The test was terminated when the sample lost its bearing capacity, as evidenced by a significant decrease in stress and the absence of a rebound trend. During this process, peak stress, maximum strain, and other relevant data were recorded, and photographs of the damaged samples were taken for further analysis.

Layout of AE device

The AE system was used to collect key parameters such as the energy, cumulative energy, ringing count, and cumulative ringing count during the loading process. In this context, “energy” refers to the energy released as the material’s internal structure develops under load, while “ringing count” represents the number of ringing pulses exceeding a preset threshold, reflecting the frequency of AE signals. The AE energy and ringing count were used to determine the failure characteristics of the rock’s internal structure during uniaxial compression. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 10.

A DS5 AE system was used to monitor the generation and development of internal cracks in the rocks under loads. The primary parameters are listed in Table 3.

Four sensor probes distributed symmetrically in the soft and hard rocks were used in the test. The arrangement of the resistive strain gauges and AE probes is shown in Fig. 11.

Test results

Stress–strain curve analysis

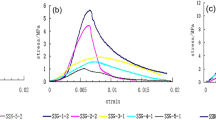

Under the axial load, the axial stress of the sample increases with axial strain, reflecting the material’s elastic modulus and strength characteristics. The stress–strain curve for the composite rock mass specimen was experimentally obtained and is presented in Fig. 12.

The uniaxial compressive strength of the composite rock mass is represented by the peak stress, which characterizes the sample’s bearing capacity. The peak stress values of each sample are shown in Fig. 11, and a relationship curve between the sample strength and thickness of the soft rock layer is plotted in Fig. 13.

As the proportion of the soft rock thickness increased, the strength of the composite samples gradually decreased. Specifically, when the soft rock layer thickness ratio was 10%, the strength of the composite rock mass sample was 45.12 MPa. At a 90% soft-rock thickness, the strength reduced to 16.8 MPa. When the soft rock thickness increased from 10% to 20%, the strength of the composite rock mass decreased by 9.22%. However, when the soft rock thickness increased from 80% to 90%, the strength decreased by 7.10%.

To further investigate the relationship between the composite rock mass strength and the proportion of soft rock layer thickness, the data were processed using both linear and single exponential decay function fittings.

Linear fitting results:

where \({\sigma _{peak}}\) is the peak stress of the combined specimen.

Single exponential decay function fitting results:

Both fitting methods effectively captured the change in sample strength with respect to the soft rock thickness. When the soft rock thickness was small, the constraint effect of the hard rock was significant, causing a rapid decrease in sample strength. As the soft rock layer became thicker, the rate of strength decline slowed, with the strength being primarily governed by the soft rock layer itself.

The elastic modulus, which is obtained from the slope of the linear elastic section in the stress–strain curve, reflects the axial deformation capacity of the specimen under loading. It is often used to characterize the deformation properties of a sample, as shown in Fig. 14.

The elastic modulus of the composite rock mass decreased monotonically as the thickness ratio of the soft rock layer increased. When the soft rock layer thickness was 10%, the elastic modulus of the sample was 9.77 GPa. For a sample with a soft rock thickness ratio of 90%, the elastic modulus decreased to 6.17 GPa. When the thickness of the soft rock layer increased from 10% to 20%, the elastic modulus of the composite rock mass decreased by 7.88%. Conversely, the sample with 90% soft rock layer exhibited a 5.06% decrease in elastic modulus compared to the 80% soft rock layer sample.

Linear fitting results:

where \(E\) represents the elastic modulus of composite rock mass.

Single exponential decay function fitting results:

The fitting degrees of both methods were greater than 0.98, with the single exponential decay function providing a higher degree of fit. As the proportion of soft rock thickness increased, the elastic modulus of the composite rock mass gradually decreased. The rate of change in the elastic modulus exhibited a significant downward trend as the proportion of soft rock thickness increased.

Failure characteristics of combined rock mass

The ringing distribution ratio is defined as the ratio of the current cumulative ringing count to the total ringing count when the specimen fails. This ratio is used to describe the damage to the sample. The ringing count curve of the sample was plotted, accompanied by the corresponding failure diagram and the final failure physical diagram, as shown in Figs. 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19.

In Figs. 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19: (a) AE characteristics and final sample destruction, (b) samples damaged at various.

During the compaction stage, the original cracks in the sample gradually closed, resulting in a minimal number of acoustic emission signals. The cumulative number of ringing was less than 5% of the total ringing count when the sample failed. Due to the higher initial porosity of the hard rock layer, as the thickness ratio of the soft rock layer increased, the ringing distribution ratio of the sample during compaction decreased from 2.57% to 1.10%, and the acoustic emission signal became more subdued.

In the elastic stage, the ringing distribution ratio showed slight changes. As the soft rock layer thickness increased, the growth rate of the cumulative ringing count in the combined rock mass during the elastic stage decreased, causing the sample to enter the plastic stage earlier. For a soft rock layer thickness of 10%, the total number of ringing in the elastic stage increased by 5.27%. However, for a soft rock layer thickness of 90%, the growth rate of the ringing distribution ratio was only 2.52%, and the duration of the elastic stage was 80% for the sample with a 10% soft rock thickness.

During the plastic stage, new cracks continuously formed, and existing cracks continued to propagate, resulting in a significant increase in the acoustic emission signals and a sharp change in the ringing distribution ratio. At the end of the plastic stage, the number of ringing in the composite rock mass reached 40% of the total ringing count at failure. As the soft rock thickness ratio increased, the growth rate of the ringing distribution ratio slowed, while the duration of the plastic stage increased from 200 s for the sample with 10% soft rock thickness to 600 s for the sample with 90% soft rock thickness.

When the soft rock layer was relatively thin, surface cracks initially formed in the soft rock layer and propagated into the hard rock layer, primarily resulting in straight cracks and splitting failure, and the number of cracks was large. However, as the soft rock thickness ratio increased, the number of surface cracks in the soft rock decreased, while the proportion of oblique cracks gradually increased. The soft rock layer transitioned from splitting failure to shear failure. When the soft rock layer thickness exceeded 70 mm, cracks were generated simultaneously in both the soft and hard rock layers. The cracks on both sides intersected with the loading on the joint surface, leading to sample failure.

In the failure stage, cracks penetrated, and the acoustic emission signals exhibited multiple peaks. At this time, the ringing distribution ratio increased rapidly, and the damage to the sample significantly escalated.

Energy evolution characteristics

Energy evolution characteristics of single rock mass

According to the law of energy conservation, the total energy within the specimen and the energy exchanged with the external environment during loading remain constant, with the failure of the sample representing a form of energy release. During loading, the specimen absorbs mechanical energy from the press and thermal energy from the environment (energy input), storing this energy as elastic strain energy (energy accumulation). As loading continues, some of this energy is converted into unrecoverable energy forms, such as plastic strain energy and damage energy.

When the sample fails, energy is released in various forms: kinetic energy from the fragments falling off, sound energy emitted during damage, and heat energy generated by overcoming the internal friction of the specimen (energy dissipation). This process is illustrated in Fig. 20.

During the loading process, both strain hardening and softening occurred simultaneously in the samples. According to the strain-hardening mechanism of the specimen, the input mechanical energy is converted into elastic strain energy, which accumulates within the specimen, resulting in elastic deformation. At the same time, part of the elastic strain energy is dissipated in the form of plastic strain energy and damage energy. The efficiency of this energy conversion depends on the strain-softening capacity of the sample. The stress–strain curve of the rock sample under uniaxial compression is shown in Fig. 21.

Note

A straight line AB parallel to the elastic stage was drawn through the peak point. The elastic strain energy density \({u_{\text{e}}}\) of the composite rock mass was determined from the area enclosed by the straight line AB and \(\varepsilon\) axis. The area enclosed by the straight line AB and the stress–strain curve represents the dissipated energy density of the composite rock mass\({u_{\text{d}}}\).

In the compaction stage, as the primary fractures gradually close, the input energy is mostly dissipated as plastic strain energy and thermal energy. During this stage, the strain-softening performance dominates and reflects the sample’s initial state. In the elastic stage, mechanical energy is converted into elastic strain energy, and the curve is approximately linear, with minimal energy dissipation. As loading continues, new cracks formed within the sample, enhancing its strain-softening capacity, although elastic strain energy remains dominant. After the specimen yields, surface damage energy increased rapidly, the capacity of elastic strain energy decreased, and the energy dissipation ratio increased. When the crack penetrates, the sample splits, and the accumulated elastic strain energy reaches its storage limit. This energy is instantly released as kinetic energy, heat, and acoustic energy. The sample enters the failure stage, and the stress decreases rapidly. The residual elastic strain energy enables the sample to maintain some residual strength.

Composite rock mass strength parameters

Elastic constant

Many researchers54,55,56 provided the same equations for the equivalent physical and mechanical properties of a layered rock mass. The elastic modulus of the soft-hard composite rock mass is given by

Poisson ‘s ratio can be solved by the following equation:

where µxz denotes the ratio of strain εz in z-direction to strain εx in x-direction under the action of stress σx in x-direction; E0s is the initial elastic modulus of soft rock; µs denotes the Poisson ‘s ratio; E0h is the initial elastic modulus of hard rock; and µh denotes the Poisson ‘s ratio.

The shear modulus of elasticity is calculated as follows:

where Gxz denotes the deformation capacity of the composite rock mass under shear stress; and Gs and Gh denote the shear moduli of the soft rock and hard rock, respectively, which can be calculated using the elastic modulus and Poisson ‘s ratio.

Peak strength

When the energy accumulated inside the composite rock mass reaches its limit, the surface damage energy increases suddenly, and the sample is considered damaged. For a single rock mass, the relationship between the maximum elastic strain energy and peak strength is given by

where \({u_{{\text{e,max}}}}\) is the maximum elastic strain energy density of the rock under uniaxial compression, \({\sigma _c}\)is the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock, and \({E_0}\) is the initial elastic modulus.

For the combined rock mass, when the energy in the soft rock layer approaches its limit, energy accumulation in the soft rock layer is inhibited, and the input energy accumulates in the hard rock layer. Damage occurs when the energy inside the sample reaches the energy storage limit. The maximum elastic strain energy of the composite rock mass is given by

Under unidirectional load, the peak strength of composite rock mass is given by

where Ez is the axial elastic modulus of the composite rock mass, \({E_z}=\left( {1 - D} \right){E_{z0}}\); and V is the sample volume, \(V={V^s}+{V^h}\).

Energy evolution characteristics of composite rock mass

Pre-peak stage

As shown by the red dotted line in Fig. 20, the area of the pre-peak stage on the curve represents the work performed by the press; the input energy density of the composite rock mass was \({u_{\text{c}}}\). A straight line AB parallel to the elastic stage was drawn through the peak point. The elastic strain energy density \({u_{\text{e}}}\) of the composite rock mass was determined from the area enclosed by the straight line AB and \(\varepsilon\) axis. The area enclosed by the straight line AB and the stress–strain curve represents the dissipated energy density of the composite rock mass \({u_{\text{d}}}\). Ignoring the energy released in the pre-peak stage, the following relationship exists:

The strain-hardening coefficient \({\xi ^{\text{h}}}\) and strain-softening coefficient \({\xi ^{\text{s}}}\) are used to characterize the ability of the composite rock mass to transform from input energy to elastic strain energy, and from elastic strain energy to dissipated energy, respectively. According to the law of mutual promotion and inhibition of energy, the strain-hardening coefficient \({\xi ^{\text{h}}}\) and strain-softening coefficient \({\xi ^{\text{h}}}\) are not constant. The higher the elastic energy accumulated in the composite rock mass, the lesser the elastic energy converted from the input energy, thus reducing the strain-hardening coefficient \({\xi ^{\text{h}}}\). Similarly, as dissipated energy increases, it inhibits subsequent energy dissipation, leading to a decrease in the strain-softening coefficient \({\xi ^s}\).

From \({t_0}\) to \({t_1}\), the stress increase \(d\sigma\), the strain increase \(d\varepsilon\), the input energy density change \(\Delta {u_{\text{c}}}\), the elastic strain energy density change \(\Delta {u_{\text{e}}}\), and the dissipated energy density change \(\Delta {u_{\text{d}}}\) of the sample are given by

The relationship between energy density and stress of rock after loading is given by

where \({u_{\text{i}}}\) is the energy density transformed in a certain energy conversion process; \({u_{{\text{ci}}}}\) is the source energy density that drives the conversion; \({u_{{\text{i0}}}}\) is the minimum energy density required for the conversion process to occur; \(\:k,r\) is the coefficient; \({a_i}\) and \({b_i}\) reflect the degree of energy conversion and inhibition of conversion, respectively; and \(C\) is the integral constant.

Based on the uniaxial compression test of soft and hard rock, a set of parameters can be determined to characterise the input energy density evolution model and the elastic strain energy density evolution model during loading.

For the soft-hard composite rock mass, under a certain stress level \(\sigma\), the energy densities of the soft and hard rock layers can be calculated as shown in Eq. 19. Therefore, the input and elastic strain energies of the entire composite rock mass can be expressed as follows:

Post-peak stage

In the post-peak stage, the composite rock mass quickly converts the elastic strain energy stored in the early stage into released energy. The conversion coefficient \(\alpha\) refers to the parameter proposed by ZHAO et al.57,58,59 to quantify rock energy damage:

where \({U_{{\text{e,max}}}}\) is the maximum elastic strain energy stored.

Damage constitutive equation

Establishment of damage constitutive equation

Deformation localisation occurs in the rock mass under external loading which manifests as the aggregation of meso-fractures within the rock mass. This macroscopic behaviour is influenced by the thickness ratio of the soft and hard rock masses. Based on the Weibull distribution theory and considering the effect of the thickness ratio of composite rock mass on macroscopic deformation localization, a damage constitutive equation was established.

Under external loading, damage accumulates gradually until complete failure occurs, representing a continuous process. It is assumed that the mechanical properties of the damaged area follow the Weibull statistical law. The density distribution function is shown in Eq. 22.

Assuming that the total number of damaged elements is \({N_f}\), when the strain of the composite rock mass reaches a certain value, the overall damage variable \(D\) of the composite rock mass is the ratio of the total number of damaged elements to the total number of elements.

The number of damaged units can be calculated when the strain value of the combined rock mass reaches \(\varepsilon\):

The damage variables can be obtained by substituting Eqs. (22) and (24) into Eq. (23).

Applying Lemaitre’s strain equivalence principle for isotropic elastic damaged materials, the damage parameter \(D\) is introduced into the elastic equation, and the constitutive relation of the damaged region can be written as:

To derive the damage constitutive model for deformation localisation in the soft-hard composite rock masses, the following assumptions were made:

(1) The soft and hard rocks are regarded as isotropic.

(2) The interface between the soft and hard rock layers is perfectly bonded, with no filling material, and there is no relative slip under unidirectional loading. The rock layers deform co-ordinately.

(3)The soft rock area is considered a localized area, while the hard rock area is non-localized. Under the action of external load, it is assumed that the hard rock area is not damaged and always maintains an elastic state. In the soft rock area, mesoscopic damage follows the Weibull distribution. As the load increases, damage accumulates in the soft rock area, whereas damage in the hard rock area is negligible in comparison. The soft rock thickness ratio \(\beta\) is introduced as a deformation localisation parameter for the composite rock masses. The damage model for the soft-hard composite rock masses is shown in Fig. 22.

Determination of model parameters

For the overall stress–strain relationship \(\left( {\sigma ,\varepsilon } \right)\) of the soft-hard composite rock mass, the localized area of soft rock and the non-localized area of the hard rock are connected in series. The stress–strain relationship for both the entire composite mass and individual regions are given by Eqs. (27) and (28), respectively.

In the hard rock area, the rock maintains elastic deformation and does not fail. Therefore, the constitutive relationship of the area is described in Eq. (29). The constitutive relationship of the soft rock area is described in Eq. (26).

Substituting Eqs. (26) and (29) into (27), the strain relationship between the localised region of the soft rock and the nonlocalized region of the hard rock can be obtained, as shown in Eq. (30).

Equation (30) is a quadratic equation with one variable, and two solutions to \({\varepsilon ^s}\)can be obtained by solving it.

Equation (30) shows that, when the peak point appears in \(1+{m^2} - 2me{\varepsilon ^h}=0\), the strain values \({\varepsilon ^s}\) and \({\varepsilon ^h}\) of the two regions when the composite rock mass is at its peak strength can be obtained as follows:

The macroscopic damage parameter \(M\) and \({\varepsilon _0}\) of the rock mass were determined using the peak point \(\left( {{\sigma _c},{\varepsilon _c}} \right)\) of the rock stress–strain curve. The relationship between \(M\) and \({\varepsilon _0}\) can be obtained by substituting Eq. (33) and the peak point \(\left( {{\sigma _c},{\varepsilon _c}} \right)\) in Eqs. (27) and (28).

Equations (34) and (32) were substituted into Eq. (28) for solving, and the calculation parameters were obtained.

Model validation

As shown in Fig. 23, the results indicate that this constitutive model exhibits high consistency with experimental data during the pre-peak stage, with a root mean square error of 0.5% and a mean absolute error of 0.56%. This demonstrates the model’s capability to accurately describe the pre-peak stage of stress-strain curves in composite rock bodies. The parameters employed possess precise physical significance, reflecting the strength and deformation behaviour of composite rock bodies with varying layer thickness ratios. This simplifies the solution process for damage models. However, the model exhibits certain limitations: while the post-peak curve morphology generally aligns with experimental data, strain values exhibit deviations. This may stem from significant crack propagation within the rock specimen and relative displacement between blocks, leading to pronounced volumetric expansion and deformation. Consequently, the model fails to capture specimen failure behaviour beyond the peak point.

Conclusions

In this study, based on similarity theory, soft-hard composite rock mass samples with different layer thickness ratios were prepared, and a uniaxial compression test system was used to investigate the influence of layer thickness ratios on the soft-hard composite rock mass. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) As the proportion of soft rock increases, both the uniaxial compressive strength and elastic modulus of composite rock masses exhibit a decreasing trend. The rate of decline in elastic modulus diminishes with increasing soft rock content; when the soft rock thickness ratio increases from 10% to 90%, the peak strength decreases by 63%.

(2) The thickness of the soft rock layer increased, causing the plastic stage of the specimens to gradually lengthen from 200 s to 600 s. The rate of change in the distribution ratio of ringing within the plastic stage decreased, and fracture development slowed. The number of surface cracks gradually diminished, but oblique cracks progressively increased. The failure mode transitioned from splitting failure to shear failure.

(3) Based on the law of energy conservation, under unidirectional loading, most of the input energy was converted into internal elastic strain energy and dissipation energy. The relationship between the energy evolution and thickness ratio was constructed using the elastic constant and peak strength.

(4) A damage variable of the soft-hard composite rock mass was established using the Weibull distribution strength theory. A damage constitutive model was created, taking into account the localization of macroscopic deformation caused by the layer thickness ratio. The model accurately fitted the pre-peak stress–strain curves of the composite soft-hard composite rock mass under unidirectional loading.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of interlayer material on dynamic mechanical properties of rock mass with combined hard and soft Media[J]. Explosion Shock Waves. 43 (12). https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2023-0022 (2023).

Huang, M. et al. Experimental technology for the shear strength of the Series-Scale rock joint Model[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53 (12), 5677–5695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02241-w (2020).

Gao, Y-T., Wu, T-H. & Zhou, Y. Application and prospective of 3D printing in rock mechanics: A review[J]. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater. 28 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-020-2119-8 (2020).

Niu, Q. et al. Application and prospects of 3D printing in physical experiments of rock mass mechanics and engineering: materials, methodologies and models[J]. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-023-00567-8 (2023).

Jiang, C. et al. Investigation of dynamic crack coalescence using a Gypsum-Like 3D printing Material[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49 (10), 3983–3998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-0967-3 (2016).

Zhuang, D. et al. Investigation on mechanical properties regulation of rock-like specimens based on 3D printing and similarity quantification[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 34 (5), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2024.05.004 (2024).

Xia, Y. et al. Mechanical behavior of structurally reconstructed irregular columnar jointed rock mass using 3D printing[J]. Eng. Geol. 268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105509 (2020).

Cheng, J-L. et al. Uniaxial experimental study of the acoustic emission and deformation behavior of composite rock based on 3D digital image correlation (DIC)[J]. Acta. Mech. Sin. 33 (6), 999–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10409-017-0706-3 (2017).

Xie, Q. et al. Influence of layer thickness ratio on the mechanical and failure properties of Soft-Hard interbedded Rock-like Material[J]. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27 (11), 4962–4977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-023-0398-0 (2023).

Zuo, J., Chen, Y. & Song, H. Study progress of failure behaviors and nonlinear model of deep Coal-rock combined Body[J]. J. Cent. South. Univ. 52 (8). https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7207.2021.08.002 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Natural joint effect on mechanical characteristics and fracture evolution of In-Site rocks under uniaxial compression[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107880 (2024).

Zuo, T. et al. Insights into natural tuff as a Building material: effects of natural joints on fracture fractal characteristics and energy evolution of rocks under impact load[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108584 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. Influence of primary interface characteristics on mechanical properties and damage evolution of coal-rock combination[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108658 (2024).

Zhang, K., Wang, L. & Meng, G. Monitoring warning criterion of acoustic emission active waveguide system based on loess deformation and failure[J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62030-1 (2024).

Kumar, D., Mahapatro, A. K. & Singh, S. K. Active waveguide deformation dynamics using acoustic emission technology for landslide early warning system[J]. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83 (2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03548-6 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Acoustic emission characteristics of graded loading intact and Holey rock samples during the damage and failure Process[J]. Appl. Sci. 9 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/app9081595 (2019).

Wang, K. et al. The instability mechanisms and precursor information of different type rocks based on acoustic emission[J]. PLOS One. 20 (5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0322126 (2025).

Zheng, K. et al. A dominant frequency-based hierarchical clustering method for evaluating the mode-II fracture mechanisms of shale using the acoustic emission technique. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104644 (2024).

Lian, S. et al. Study on the freezing-thawing damage mechanism and evolution model of saturated Gray sandstone based on NMR and AE technology. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84 (11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-025-04592-6 (2025).

Lin, H., Li, S. & Zhang, X. Macro-micro failure and crack coalescence behavior of soft-hard composite rock with three parallel joints under uniaxial compression[J]. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 2947–2958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.02.029 (2024).

Zuo, J. & Chen, Y. Investigation on crack recovery effect of Coal-rock combined body under the influence of Unloading[J]. J. China Coal Soc. 42 (12). https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2017.0682 (2017).

Wang, S. & Xu, W. A coupled elastoplastic anisotropic damage model for rock materials[J]. Int. J. Damage Mech. 29 (8), 1222–1245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056789520904093 (2020).

Zhou, F. & Cheng, G. A coupled plastic damage model for concrete considering the effect of damage on plastic Flow[J]. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/867979 (2015).

Bakhti, R. et al. New approach for computing damage parameters evolution in plastic damage model for concrete[J]. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00834 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. A rate- and pressure-dependent damage-plasticity constitutive model for rock[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104394 (2020).

Zhang, H., Lei, L. & Yang, G. Characteristic and representative model of rock damage process under constant confining Stress[J]. J. China Univ. Mining-Technology. 44 (1). https://doi.org/10.13247/j.cnki.jcumt.000279 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Analysis of damage evolution characteristics of jointed rock mass with different joint dip Angles[J]. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 51 (8). https://doi.org/10.11918/j.issn.0367-6234.201805091 (2019).

Zhao, G., Xie, L. & Meng, X. A damage-based constitutive model for rock under impacting load[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 24 (4), 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2014.05.014 (2014).

Gu, T. et al. A dynamic damage constitutive model considering the effect of joint inclination on the modulus of elasticity of slates[J]. Sci. Rep. 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94233-5 (2025).

Manogharan, P. et al. Experimental investigation of elastodynamic nonlinear response of dry intact, fractured and saturated rock[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55, 2665–2678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02552-6 (2022).

Bai, H. et al. Modelling of non-linear elastic constitutive relationship and numerical simulation of rocks based on the Preisach–Mayergoyz space model[J]. Geophys. J. Int. 239 (3), 1517–1529. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggae341 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparative study of multiple statistical damage mechanics models for rock behaviors under high temperature[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138049 (2024).

Chen, K. Constitutive model of rock triaxial damage based on the rock strength statistics[J]. Int. J. Damage Mech. 29 (10), 1487–1511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056789520923720 (2020).

Ji, M. et al. Constitutive model of rock uniaxial damage based on rock strength Statistics[J]. Adv. Civil Eng. 2018 (1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5047834 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. An improved statistical damage constitutive model for rock considering the temperature Effect[J]. Int. J. Geomech. 22 (11). https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0002571 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. A statistical damage-based constitutive model for shearing of rock joints in brittle drop mode[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 34 (8), 1041–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2024.08.007 (2024).

Lian, S. et al. Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology. Reviews Adv. Mater. Sci. 63 (1). https://doi.org/10.1515/rams-2024-0034 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Transparent analysis of compression damage propagation of freeze-thaw rock based on CT-DVC. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 239 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2025.104593 (2025).

Lin, H. et al. Comparative analysis of rock damage models based on different distribution Functions[J]. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 40 (1), 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-021-01899-5 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Comparative study on three-dimensional statistical damage constitutive modified model of rock based on power function and Weibull distribution[J]. Environ. Earth Sci. 77 (3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-018-7297-6 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Damage constitutive model of RAC under triaxial compression based on Weibull distribution function[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138499 (2024).

Gu, Q. et al. Shear fracture behavior and damage constitutive model of rock joints considering the effect of pre-peak Cyclic loading[J]. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104289 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Study on the Weibull distribution function-based stochastic damage evolution law for uniaxial compression in high-performance concrete with full aeolian sand[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138461 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Cracking behavior of rock containing non-persistent joints with various joints inclinations[J]. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2020.102701 (2020).

Lian, S., Wan, W., Zhao, Y., Wu, Q. & Du, C. Investigation of the mechanical behavior of rock-like material with two flaws subjected to biaxial compression. Sci. Rep. 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64709-x (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Damage evolution characteristics of freeze–thaw rock combined with CT image and deep learning technology. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-04010-3 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Compression Mechanical Properties and Constitutive Model for Soft–Hard Interlayered Rock Mass[J]. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2024, 1–18 https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/1693495 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Deformation characteristics and damage ontologies of soft and hard composite rock masses under impact loading[J]. J. Mt. Sci. 21 (5), 1715–1727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-023-8348-3 (2024).

Ambrose, R. J. et al. Shale Gas-in-Place calculations part I new Pore-Scale Considerations[J]. SPE J. 17 (1), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.2118/131772-pa (2012).

Wang, Q. et al. Micro- to nano-scale areal heterogeneity in pore structure and mineral compositions of a sub-decimeter-sized eagle Ford Shale[J]. Int. J. Coal Geol. 261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2022.104093 (2022).

Tian, H. et al. Influence of Pore Water on the Gas Storage of Organic-Rich Shale[J]. Energy Fuels, 34(5): 5293–5306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b03415. (2020).

Ross, D. J. K. & Marc Bustin, R. The importance of shale composition and pore structure upon gas storage potential of shale gas reservoirs[J]. Mar. Pet. Geol., 26(6): 916–927. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2008.06.004. (2009).

Chen, Y. et al. Multiscale characterization of shale pore-fracture system: geological controls on gas transport and pore size classification in shale reservoirs[J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108442 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Advancements in laboratory studies of layered rock masses for deep engineering: insights and future Perspectives[J]. J. Earth Sci. 36 (3), 1334–1340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12583-025-2032-1 (2025).

Yin, P-F. & Yang, S-Q. Experimental investigation of the strength and failure behavior of layered sandstone under uniaxial compression and Brazilian testing[J]. Acta Geophys. 66 (4), 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-018-0152-z (2018).

Tian, Y. et al. Analytical model of layered rock considering its Time-Dependent Behaviour[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54 (11), 5937–5944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02421-2 (2021).

Gong, F-Q., Wang, Y-L. & Luo, S. Rockburst proneness criteria for rock materials: review and new insights[J]. J. Cent. South. Univ. 27 (10), 2793–2821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-020-4511-y (2020).

Zhang, Z. X. et al. Effects of loading rate on rock fracture fracture characteristics and energy partitioning[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 37 (1), 745–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(00)00008-3 (2000).

Wu, P. F. et al. Investigations on mechanical properties and crack propagation characteristics of coal and sandy mudstone using three experimental Methods[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 50 (1), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1048-3 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the funding of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.42401160), Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (NO2024JC-YBQN-0258).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jin-Hua Li: Methodology, Validation, Project administration; Yan-Long Li: Conceptualization; Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; Pan Wang: Data Curation, Funding acquisition; Wen-Xiang Liu: Supervision, Visualization; Yang Yang: Resources, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, JH., Li, YL., Wang, P. et al. Effect of thickness ratio on uniaxial mechanical behavior of soft-hard composite rock masses: experimental analysis and modeling. Sci Rep 15, 44355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27986-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27986-8