Abstract

Branchiostoma malayanum is a poorly studied amphioxus species within the family Branchiostomatidae, with limited genomic resources available to support its taxonomic and evolutionary characterization. In this study, we present the first complete mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum and assess its phylogenetic position through a combination of morphological characterization, mitogenomic analysis, and comparative genetic divergence. The assembled mitogenome is 15,154 base pairs in length, encoding 13 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs, and 2 rRNAs, with conserved gene order and a strong AT bias (63.46%). Codon usage analysis revealed compositional asymmetry and functional constraints typical of cephalochordates. Morphological measurements showed a mixture of conserved segmental traits and variable external features influenced by developmental allometry. Comparative analysis of four mitochondrial markers (COX1, Cytb, 12 S rRNA, 16 S rRNA) demonstrated substantial intergeneric divergence among Branchiostoma, Asymmetron, and Epigonichthys, and supported the distinctiveness of B. malayanum from its congeners. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on complete mitogenomes positioned B. malayanum within a derived clade of Branchiostoma, closely related to B. belcheri and B. japonicum. These findings confirm the independent evolutionary status of B. malayanum and highlight the value of mitogenomic data in resolving cephalochordate diversity and systematics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The phylum Chordata is composed of three major subphyla: Vertebrata (vertebrates), Cephalochordata (cephalochordates), and Urochordata (tunicates). Among them, the subphylum Cephalochordata represents an early-diverging lineage within chordates and is represented today solely by amphioxus, a small, marine, benthic organism that has remained morphologically conserved over hundreds of millions of years. Cephalochordates are regarded as the most proximate living relatives of vertebrates, sharing fundamental chordate features such as a notochord, dorsal nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, and segmented muscle blocks (myomeres), but lacking complex organs such as a true brain, heart, and paired appendages. Due to its early-diverging phylogenetic position and conserved body plan, amphioxus—commonly referred to as lancelet—is often termed a “living fossil” and serves as a critical model organism for studying the evolutionary transition from invertebrates to vertebrates1,2. Amphioxus occupies a unique position in evolutionary and developmental biology, offering essential insights into the ancestral state of chordates. Its significance as a model organism is well recognized, particularly in the fields of comparative genomics, Evo-Devo (evolutionary developmental biology), and molecular phylogenetics. The sequencing of the amphioxus genome, particularly that of Branchiostoma floridae, has revealed an exceptionally conserved genomic architecture that parallels that of early chordates3,4. Unlike vertebrates, amphioxus has not undergone whole-genome duplications (WGDs), which are considered a key factor in vertebrate complexity. The lack of WGD makes the amphioxus genome an ideal reference for reconstructing ancestral chordate gene structures and understanding the genomic innovations that accompanied the origin of vertebrates5,6.

Genomic studies have identified numerous gene families and regulatory networks that are conserved between amphioxus and vertebrates, including genes involved in neural patterning, somite formation, and endocrine signaling2,7. These studies suggest that the fundamental genetic toolkit required for vertebrate body plan development was already present in the common ancestor of cephalochordates and vertebrates. Moreover, transcriptomic and epigenomic data have further highlighted the deep conservation of gene expression patterns and chromatin organization, emphasizing the utility of amphioxus in comparative studies of gene regulation. Morphologically, amphioxus is characterized by a slender, laterally compressed, and semi-transparent body typically ranging from 2 to 8 cm in length. It retains several chordate features throughout its life, including a dorsal nerve cord, a persistent notochord that extends from head to tail, and a series of pharyngeal slits used in filter feeding8,9. The organism lacks highly differentiated organ systems found in vertebrates. Instead of a centralized brain, amphioxus possesses a simple cerebral vesicle, and its circulatory system is devoid of a heart, relying on contractile vessels to propel blood10. Reproduction is generally sexual with external fertilization, and developmental processes are well-characterized, showing remarkable similarities to vertebrate embryogenesis during early stages11,12. Ecologically, amphioxus inhabits shallow coastal waters, typically in sandy or muddy sediments at depths ranging from 5 to 50 m. It exhibits burrowing behavior, usually embedding itself vertically in the substrate with only its anterior end protruding to facilitate filter feeding13,14. Amphioxus is primarily nocturnal, remaining buried during the day to avoid predation and becoming more active at night. It prefers fully marine conditions with salinities ranging between 30 and 35 PSU and is commonly found in oxygen-rich, transparent waters. Its diet mainly consists of diatoms and protozoans such as Coscinodiscus, Navicula, Cyclotella, Chaetoceros, and Nitzschia. Buccal cirri surrounding the mouth help trap microscopic food particles, which are then directed through pharyngeal slits into the digestive tract while excess water is expelled15,16. Taxonomically, the classification of amphioxus has long been a subject of debate, particularly due to the intraspecific variability in morphological traits such as body size, pigmentation, and myomere count. Currently, the subphylum Cephalochordata includes three recognized genera: Branchiostoma, Asymmetron, and Epigonichthys. Of these, Branchiostoma is the most species-rich, with over 20 described species9,17. The genera Asymmetron and Epigonichthys are comparatively less diverse but exhibit distinctive morphological and reproductive traits. Geographically, Branchiostoma species are broadly distributed across the Indo-West Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic Ocean, while Asymmetron and Epigonichthys are generally confined to tropical and subtropical regions along the equator18.

The advent of molecular phylogenetics has significantly improved our understanding of amphioxus taxonomy and evolutionary history. Analyses based on mitochondrial DNA (e.g., COI, 16 S rRNA), nuclear genes, and complete mitogenomes have revealed substantial cryptic diversity within amphioxus populations. These approaches have facilitated the resolution of previously ambiguous species boundaries and provided new insights into biogeographic patterns and evolutionary trajectories19,20. Notably, comparative mitochondrial studies have identified several genetically distinct lineages within what were previously considered single species, indicating the need for taxonomic revisions17,18. In the West Pacific, for instance, Branchiostoma belcheri has historically been regarded as a widespread species. However, detailed molecular studies have revealed that B. belcheri comprises at least two genetically distinct lineages. Zhong, et al.21 sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes from several B. belcheri populations and found that individuals from Qingdao and Japan, along with B. japonicum from Xiamen, clustered within the same clade, while populations from Maoming and other parts of Xiamen formed a separate lineage. These findings support the notion that B. belcheri and B. japonicum are distinct species, thus refining our understanding of amphioxus diversity and distribution in the region. Amphioxus populations have been recorded extensively across China’s coastal regions. In southeastern China, B. belcheri was first documented in Xiamen Bay nearly a century ago and was once considered a local fishery resource due to its abundance22. In northern China, B. belcheri tsingtauense was described in Qingdao and later reclassified as B. japonicum based on genetic evidence22,23. Amphioxus species have also been recorded in Japan24, Taiwan25, and Australia26, indicating a wide Indo-West Pacific distribution.

In the Pearl River Estuary and surrounding waters, five amphioxus species have been identified to date: three from the genus Branchiostoma (B. belcheri, B. japonicum, and B. malayanum) and two from Epigonichthys (E. cultellus and E. lucayanus). Among them, the three Branchiostoma species are found in relatively high abundance, while the Epigonichthys species are rare and recorded only sporadically27. Remarkably, B. malayanum, previously thought to be restricted to Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand, Singapore, and the Solomon Islands)9, was recorded for the first time in the South China Sea in 2007, suggesting a broader distribution than previously assumed28. Despite significant advances in amphioxus taxonomy and phylogenetics, many questions remain unresolved. The evolutionary relationships among the three extant genera and within the family Branchiostomatidae are still being refined. In particular, the placement of B. malayanum, a dwarf species that differs morphologically from other congeners, has not been fully elucidated. To address this knowledge gap, comprehensive comparative analyses using complete mitochondrial genomes, combined with morphological data and geographic distribution, are essential.

In this study, we sequenced, assembled, and annotated the complete mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum for the first time. We also compared morphological traits among Branchiostoma populations from the Pearl River Estuary and conducted phylogenetic analyses using complete mitochondrial genomes from 10 of the 30 recognized species within the Branchiostomatidae family. Our specific objectives were to (1) determine the phylogenetic position of B. malayanum and (2) investigate evolutionary relationships across different subfamilies of Branchiostomatidae. This research provides new insights into amphioxus diversity and contributes to a deeper understanding of cephalochordate evolution and biogeography.

Results

Morphological traits

Morphological characteristics of B. malayanum under light microscopy was showed in Fig. 1. The B. malayanum exhibited relatively high individual variation in total length (TL), body height (BH), the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA), the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF), with coefficients of variation (CV) ranging from 24.7 to 63.3% (Fig. 2). Among these traits, the lengths of posterior to the anus (LPA) showed the highest degree of variation, with a CV of 63.3% (Fig. 1). In contrast, the myotomes count anterior to anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), as well as the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal (NFCD, NFCP) exhibited lower variation, with CVs ranging from 13 to 20% (Fig. 2).

Morphological characteristics of Branchiostoma malayanum under light microscopy. (a) Lateral view of a whole adult specimen, showing the slender, laterally compressed body and pointed rostrum. (b) Close-up of the anterior end, highlighting the buccal cirri and oral hood. (c) Magnified view of the midbody region, illustrating the segmented myomeres arranged in a V-shaped pattern. Scale bars: 4 mm (a), 100 μm (b), 500 μm (c).

Intraspecific coefficient of variation for the morphological traits of Branchiostoma malayanum; the number of myotomes anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal regions (NFCD, NFCP), total length (TL), body height (BH), caudal fin height (CFH), rostral fin length (RFL), and rostral fin height (RFH) the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA) the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF).

The results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the morphological traits of B. malayanum indicated that eight traits—total length (TL), body height (BH), lengths of segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA), lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF ), and caudal fin height (CFH)—had a greater contribution to the first principal component. In contrast, the myotomes count anterior to anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal (NFCD, NFCP) had a greater contribution to the second principal component (Fig. 3). The allometric growth indices of total length (TL) with segments lengths anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF), and body height (BH) in the B. malayanum were all close to 1 (Fig. 3). As the total length of the B. malayanum increases, these traits exhibited isometric growth. The allometric growth index of total length (TL) with the total number of myotomes (TNM) was significantly less than 1, indicating an allometric relationship between these two traits (Fig. 4). As the total length of the B. malayanum increased, the increase in myotomes number is relatively small.

Biplot of principal component analysis (PCA) for the morphological traits parameters of Branchiostoma malayanum; the number of myotomes anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal regions (NFCD, NFCP), total length (TL), body height (BH), caudal fin height (CFH), rostral fin length (RFL), and rostral fin height (RFH) the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA) the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF).

Allometric growth relationships between body length and other morphological traits of Branchiostoma malayanum; the number of myotomes anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal regions (NFCD, NFCP), total length (TL), body height (BH), caudal fin height (CFH), rostral fin length (RFL), and rostral fin height (RFH) the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA) the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF).

Mitogenome structure

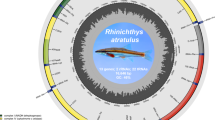

The mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum is a closed circular DNA molecule with a total length of 15,154 base pairs (GenBank accession number: PV546308). The overall nucleotide composition is biased towards adenine and thymine, with proportions of A (26.32%), T (37.15%), G (22.59%), and C (13.94%), resulting in a pronounced AT content of 63.47%. The gene arrangement and composition are highly conserved, consistent with the typical organization observed in vertebrate mitochondrial genomes. The genome comprises 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA). The PCGs include cytochrome b (Cytb), two subunits of ATP synthase (ATP6 and ATP8), three subunits of cytochrome c oxidase (COX1, COX2, and COX3), and seven subunits of NADH dehydrogenase (ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, ND5, and ND6). The majority of mitochondrial genes are encoded on the heavy strand (H-strand), including 15 tRNA genes (tRNA-Pro, tRNA-Phe, tRNA-Val, tRNA-Leu, tRNA-Ile, tRNA-Met, tRNA-Trp, tRNA-Ser, tRNA-Asp, tRNA-Lys, tRNA-Arg, tRNA-His, tRNA-Ser, tRNA-Leu, and tRNA-Gly), 12 PCGs (ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, ND5, COX1, COX2, COX3, ATP6, ATP8, and Cytb), and both rRNA genes (12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA). The remaining genes, including ND6 and several tRNAs, are transcribed from the light strand (L-strand) (Fig. 5). The ribosomal RNA genes are 1,384 bp (16 S rRNA) and 845 bp (12 S rRNA) in length, respectively. Almost all 22 tRNA genes exhibit the canonical cloverleaf secondary structure, with individual gene lengths ranging from 59 to 71 base pairs. The mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum exhibits a negative A/T skew of − 0.1706 and a positive G/C skew of 0.2368, indicating a higher proportion of thymine over adenine and a higher proportion of guanine relative to cytosine.

Circular map of the complete mitochondrial genome of Branchiostoma malayanum. The figure displays the annotated mitochondrial genome structure, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. Gene names are indicated along the outer circle, with genes encoded on the majority strand shown outside the circle and those on the minority strand inside. Colors represent different gene types: protein-coding genes (blue), tRNA genes (lavender), and rRNA genes (virescent). The inner black circle represents the distribution of GC content across the mitochondrial genome, with outward projections indicating regions of above-average GC content and inward projections reflecting below-average levels. GC skew is illustrated using a color-coded system: green denotes negative GC skew, while deep purple indicates positive GC skew. The map was generated using the CGView Server.

The protein-coding genes (PCGs) of the B. malayanum mitochondrial genome span a total of 11,291 base pairs, accounting for 74.02% of the entire mitogenome. This region exhibits a marked AT bias, with an A + T content of 62.89%, and encodes a total of 3,752 amino acid residues. Among the 13 PCGs, ND6 is the only gene encoded on the light strand (L-strand), while the remaining genes are located on the heavy strand (H-strand). The longest PCG is ND5, comprising 1,797 bp and encoding 598 amino acids, whereas the shortest is ATP8, with a length of 165 bp, encoding 54 amino acids. Initiation codons are predominantly ATG across the genome; however, two genes (COX1 and ND1) initiate with the alternative start codon GTG. All PCGs terminate with complete stop codons: eight genes (Cytb, COX2, ATP6, COX3, ND3, ND4L, ND5, and ND6) end with TAA, and five genes (ND1, ND2, COX1, ATP8, and ND4) terminate with TAG (Table 1). The mitogenome encoded 22 tRNA genes ranging in length from 63 to 71 base pairs, collectively responsible for transporting 19 different amino acids. These tRNA genes were transcribed from both the heavy (H) and light (L) strands: seven tRNAs—tRNA-Thr, tRNA-Gln, tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Cys, tRNA-Tyr, and tRNA-Glu—were encoded on the L-strand, while the remaining tRNAs were located on the H-strand. With the exception of tRNA-Ser, which lacks the dihydrouridine (DHU) stem, all other 21 tRNAs were predicted to fold into the typical cloverleaf secondary structure (Fig. 6). To investigate codon usage patterns and amino acid distribution, the amino acid composition and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the 13 protein-coding genes were analyzed in the mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum. This analysis offers insights into codon bias and the potential functional significance of amino acid composition in this species. The RSCU results indicated a preferential use of codons encoding leucine (Leu), isoleucine (Ile), phenylalanine (Phe), methionine (Met), valine (Val), and glycine (Gly), whereas codons corresponding to cysteine (Cys) were among the least frequently used (Fig. 7).

Mitochondrial genetic divergence among amphioxus genera

Genetic divergence values among the three amphioxus genera varied depending on the mitochondrial marker used (Fig. 8 and Table S2). For the COX1 gene, intra-generic divergence ranged from 0.193 ± 0.007 in Branchiostoma to 0.207 ± 0.008 in Asymmetron, while inter-generic comparisons showed the highest divergence between Asymmetron and Epigonichthys (0.271 ± 0.010) and the lowest between Branchiostoma and Epigonichthys (0.230 ± 0.007). In the cytochrome b gene, genetic divergence increased, with intra-generic values reaching up to 0.293 ± 0.018 in Epigonichthys. Inter-generic distances were highest between Asymmetron and Branchiostoma (0.359 ± 0.014) and lowest between Asymmetron and Epigonichthys (0.345 ± 0.014), indicating greater variability in this locus. For the ribosomal markers, 12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA, a similar trend of increased inter-generic divergence was observed. The 12 S rRNA gene showed the highest divergence between Asymmetron and Epigonichthys (0.386 ± 0.021) and the lowest intra-generic divergence in Asymmetron (0.215 ± 0.015). The 16 S rRNA gene also revealed pronounced inter-generic divergence, with values ranging from 0.324 ± 0.014 (Branchiostoma vs. Asymmetron) to 0.365 ± 0.016 (Epigonichthys vs. Asymmetron). Overall, the results indicate consistently high inter-generic divergence across all four mitochondrial markers, supporting clear genetic differentiation among the three amphioxus genera. The higher divergence values in ribosomal genes compared to protein-coding genes also suggest differing evolutionary rates and potential utility in resolving deeper phylogenetic relationships.

Heatmaps of pairwise genetic distances among three extant amphioxus genera (Asymmetron, Branchiostoma, and Epigonichthys) based on mitochondrial markers. Genetic divergence was estimated using the Kimura two-parameter (K2P) model, incorporating both intra- and inter-generic comparisons. Four mitochondrial loci were analyzed: two protein-coding genes (COX1 and Cytb) and two ribosomal RNA genes (12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA). Each heatmap displays median pairwise genetic distances, with color gradients reflecting increasing divergence from low (light yellow) to high (dark blue). Diagonal values represent intra-generic distances, while off-diagonal values represent inter-generic divergence. Pairwise genetic distances were estimated using the Kimura two-parameter model with 10,000 nonparametric bootstrap replicates to calculate standard errors of the distance estimates. Standard errors of the distance estimates were calculated based on the bootstrap resampling framework to ensure the statistical robustness of the analysis. Standard errors were calculated but are not displayed due to small magnitude (< 0.01).

Phylogenetic relationships within Branchiostomatidae based on mitochondrial genomes

Phylogenetic analyses based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences yielded a robust and well-resolved topology, consistently supporting the monophyly of the three recognized genera within the family Branchiostomatidae: Branchiostoma, Epigonichthys, and Asymmetron (Fig. 9). Both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods recovered congruent tree topologies, with strong statistical support across major nodes. Ciona intestinalis was used as the outgroup to root the tree. The genus Branchiostoma formed a distinct and well-supported clade (ML bootstrap support/posterior probability: 100/0.99), comprising B. belcheri, B. japonicum, B. malayanum, B. floridae, and B. lanceolatum. Within this clade, B. belcheri and B. japonicum were resolved as sister taxa with maximal support (100/0.91), and B. malayanum clustered closely with this pair, forming a subclade also supported by high nodal values (98/0.85). B. floridae and B. lanceolatum grouped together with moderate-to-high support (85/0.96), forming a early-diverging lineage within Branchiostoma. The genus Epigonichthys was recovered as monophyletic (ML/BI: 96/0.85), comprising E. cultellus and E. maldivensis, which formed a strongly supported sister-group relationship. Similarly, Asymmetron species, including A. inferum, A. lucayanum, and an undescribed Asymmetron sp., formed a well-supported clade (99/1), with A. lucayanum and Asymmetron sp. exhibiting closer affinity (96/0.92), and A. inferum occupying an early branching position (89/0.90). The intergeneric relationships revealed that Asymmetron diverged earliest among the three genera, followed by Epigonichthys, with Branchiostoma forming the most derived clade. This topology is consistent with previous findings suggesting the early-diverging position of Asymmetron within the family Branchiostomatidae. Overall, the phylogenetic reconstruction demonstrates clear genetic delineation among amphioxus genera and provides additional support for the distinct evolutionary trajectories of major lineages within cephalochordates.

Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) phylogenetic tree illustrating evolutionary relationships among amphioxus species based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences. The tree is rooted with Ciona intestinalis as the outgroup. Support values at each node are presented as ML bootstrap proportions (left) and BI posterior probabilities (right). Three well-supported clades corresponding to the genera Branchiostoma, Epigonichthys, and Asymmetron are recovered, each forming monophyletic lineages. Notably, Branchiostoma malayanum clusters closely with B. japonicum and B. belcheri, while Asymmetron lucayanum, A. inferum, and Asymmetron sp. form a strongly supported subgroup. The deeper branching of Asymmetron relative to the other two genera highlights its early divergence within the family Branchiostomatidae. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

Discussion

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in metazoans serves as a powerful model for investigating evolutionary genomics due to its relatively simple structure, maternal inheritance, and rapid evolutionary rate. The emergence of high-throughput sequencing technologies, coupled with advances in bioinformatics, has significantly enhanced the accessibility and utility of complete mitochondrial genomes. As a result, mtDNA is now extensively applied in taxonomic identification, phylogenetic reconstruction, and the study of evolutionary relationships across a wide range of freshwater and marine organisms29,30,31,32,33. The present study represents the first comprehensive morphological and mitogenomic analysis of B. malayanum within the context of the family Branchiostomatidae, integrating morphological characterization with complete mitochondrial genome sequencing and phylogenetic reconstruction. Our findings contribute significantly to understanding amphioxus systematics and mitochondrial genome evolution, and provide a clarified phylogenetic position for B. malayanum, which had previously received limited genomic attention despite its biogeographic importance in the Indo-West Pacific region. This discussion interprets our results within the broader framework of cephalochordate evolutionary biology, evaluates the implications for Branchiostomatidae taxonomy, and suggests directions for future research.

Morphological observations confirmed that B. malayanum exhibits key diagnostic features characteristic of the genus Branchiostoma, including a persistent notochord, dorsal nerve cord, V-shaped myomeres, and numerous pharyngeal slits—fundamental traits retained from the last common ancestor of chordates. These features underscore its classification within Cephalochordata and reflect the morphological conservatism long recognized in amphioxus8,9. However, our detailed morphological characterization of B. malayanum also revealed subtle but potentially significant variation in traits such as body size, pigmentation, and myomere patterning. While these characteristics broadly align with prior descriptions, they also suggest possible geographic or ecological influences, particularly in the context of the South China Sea. Intraspecific variation was most pronounced in traits associated with total body length and posterior body morphology. The coefficient of variation (CV) was highest for the length of the body segment posterior to the anus (LPA), indicating considerable variability in posterior development among individuals. In contrast, features such as myotome number and fin chamber count displayed low variability, suggesting that these segmental and structural traits are developmentally constrained and more conserved across individuals. Principal component analysis (PCA) and allometric scaling further revealed that while many external morphological traits scale proportionally with body size, others, such as myotome number, exhibit allometric patterns, possibly due to intrinsic developmental limitations. Notably, some traits in B. malayanum, such as notochord length-to-body-length ratio, ventral fin shape, and pigment stripe pattern, differed slightly from those of closely related species like B. belcheri and B. japonicum. Although often overlooked due to presumed intraspecific plasticity, these features may still contain phylogenetically informative signals, especially when interpreted alongside molecular data23,28. For example, minor differences in ventral fin positioning or pigmentation may reflect habitat-specific adaptations, such as sediment type or burrowing behavior in the Pearl River Estuary—an interpretation consistent with earlier ecological studies24. Taken together, our findings highlight both the utility and the limitations of morphology in amphioxus taxonomy. While traditional morphological markers remain essential for species identification, their resolution may be compromised by phenotypic plasticity and allometric effects. Therefore, an integrative taxonomic framework that combines morphological and molecular data is essential for resolving species boundaries and understanding evolutionary divergence within Branchiostoma.

The complete mitochondrial genome of B. malayanum exhibits structural features consistent with other members of Branchiostomatidae. The genome, spanning 15,154 bp, contains the standard 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 2 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), maintaining the gene order and orientation commonly observed across amphioxus mitogenomes. This conservation reflects strong purifying selection acting on mitochondrial genome organization in cephalochordates, likely due to the essential role of mitochondrial-encoded proteins in oxidative phosphorylation and energy metabolism33,34. The pronounced AT bias (63.46%) observed in the B. malayanum mitochondrial genome aligns with compositional trends documented in other chordates and is hypothesized to reflect thermodynamic constraints during replication and transcription. Notably, the strand-specific asymmetry (negative AT skew, positive GC skew) seen in B. malayanum matches the bias directionality reported in other amphioxus species (e.g., B. floridae, B. japonicum), suggesting evolutionary conservation of mitochondrial replication mechanisms35,36,37. An important feature revealed in our analysis is the codon usage pattern in the 13 PCGs. The predominance of codons encoding Leu, Val, Gly, and Ala—particularly TTA (Leu) and GTT (Val)—suggests translational optimization aligned with tRNA availability. Meanwhile, the underrepresentation of Cys-encoding codons points to functional constraints, possibly related to protein folding dynamics in mitochondrial enzymes. Codon usage bias, as quantified through RSCU, may also be influenced by mutational pressure and selection for efficiency and accuracy in protein synthesis38,39. Furthermore, the consistent use of ATG as an initiation codon, with rare exceptions (e.g., GTG for COX1 and ND1), and complete stop codons (TAA, TAG) across all PCGs reinforce the functional integrity of B. malayanum mitochondrial translation mechanisms. The presence of canonical cloverleaf structures in most tRNAs, except for a non-standard DHU arm in tRNA-Ser, suggests a balance between structural conservation and flexibility. These secondary structures are vital for efficient aminoacylation and codon recognition, underlining their evolutionary importance.

A core component of this study was the comparative analysis of mitochondrial genetic divergence across representative amphioxus genera. Using COX1, Cytb, 12 S rRNA, and 16 S rRNA markers, we quantified pairwise genetic distances to elucidate inter- and intra-generic variation. The results demonstrated that intrageneric divergence was consistently lowest within Branchiostoma across all loci (e.g., COX1: 0.193 ± 0.007; Cytb: 0.245 ± 0.010), followed by Epigonichthys and Asymmetron. In contrast, intergeneric comparisons showed substantially greater divergence. For instance, COX1 divergence between Asymmetron and Epigonichthys reached 0.271 ± 0.010, while divergence between Branchiostoma and Epigonichthys was 0.230 ± 0.007. The Cytb gene displayed even higher divergence values (e.g., 0.359 ± 0.014 between Asymmetron and Branchiostoma), indicating faster evolutionary rates in protein-coding loci relative to ribosomal genes17. Ribosomal RNA markers (12 S and 16 S rRNA) revealed similar patterns of divergence, albeit with slightly lower rates, consistent with their conserved functional roles. The highest intergeneric divergence observed in 12 S and 16 S rRNA (e.g., 0.386 ± 0.021 and 0.365 ± 0.016, respectively) further supports deep evolutionary separation among amphioxus genera. These values are well above typical thresholds for species-level delimitation, suggesting long-standing reproductive isolation and independent evolutionary trajectories19. The pairwise genetic distances, calculated using the Kimura two-parameter model, indicate that B. malayanum is a distinct evolutionary lineage, confirming its species-level status within the genus. These distances fall within the range of recognized interspecific divergence among amphioxus18,21, supporting earlier reports that suggested the presence of cryptic species or geographically structured lineages within Branchiostomatidae. It is particularly noteworthy that the divergence between B. malayanum and its closest relatives (e.g., B. belcheri, B. lanceolatum) was comparable to or exceeded that observed among other well-established species pairs. This result reinforces the importance of mitochondrial data in amphioxus taxonomy, particularly in contexts where morphological markers are insufficiently diagnostic. Moreover, our comparative mitogenomic framework allows for the detection of lineage-specific molecular signatures that may underpin ecological or behavioral adaptations, such as differential salinity tolerance or burrowing depth28.

Phylogenetic analyses based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences, conducted using both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods, yielded congruent and well-supported topologies that robustly resolve the evolutionary relationships within the family Branchiostomatidae. All analyses consistently recovered three strongly supported monophyletic clades corresponding to the genera Branchiostoma, Epigonichthys, and Asymmetron, with Ciona intestinalis designated as the outgroup. This phylogenetic structure aligns closely with prior mitogenomic and multi-locus studies and reaffirms the tripartite division of extant cephalochordates17,40,41. Within the Branchiostoma clade, B. malayanum was consistently placed in a well-supported lineage alongside B. belcheri and B. japonicum, forming a distinct subgroup within the genus. High bootstrap (98–100%) and posterior probability values (> 0.99) support the close phylogenetic affinity among these species, suggesting a relatively recent common ancestry28. Despite this proximity, genetic distance analyses revealed sufficient divergence to warrant their recognition as separate species, with evidence for reproductive isolation and independent evolutionary trajectories. The clustering of these species likely reflects a shared biogeographic history in the Indo-West Pacific, where they exhibit overlapping but ecologically differentiated distributions. In contrast, B. floridae and B. lanceolatum—found in the Atlantic and Mediterranean regions—formed a separate sister group, suggesting an earlier divergence potentially shaped by historical geographic isolation or ecological specialization20. The phylogenetic position of B. malayanum also provides insight into the internal diversification of Branchiostoma. While previous hypotheses proposed that B. malayanum might represent a early-diverging or transitional lineage, the current mitogenome-wide analysis places it squarely within the core of Branchiostoma, refuting notions of ambiguous taxonomic status based on earlier morphological data. Its deep divergence from B. belcheri and B. japonicum, despite morphological similarities, underscores its evolutionary distinctiveness and highlights the importance of molecular data in resolving cryptic speciation events in amphioxus. Beyond Branchiostoma, the genera Asymmetron and Epigonichthys were recovered as monophyletic sister clades, forming an early-diverging lineage relative to Branchiostoma. This topology is consistent with prior phylogenomic findings and supports the hypothesis that Asymmetron represents the earliest diverging amphioxus lineage. The early-diverging positioning of Asymmetron is further corroborated by its retention of plesiomorphic traits, such as delayed metamorphosis, reduced notochord stiffness, and distinct mitochondrial gene arrangements18. Epigonichthys—comprising E. cultellus and E. maldivensis—formed a well-supported clade and appeared as a sister taxon to Branchiostoma, reinforcing the evolutionary coherence of these three genera. While most internal nodes were supported by high bootstrap and posterior probability values, a few within the Asymmetron–Epigonichthys grouping showed moderate support (e.g., bootstrap ~ 89%, posterior probability ~ 0.85), potentially reflecting incomplete lineage sorting or mutational saturation in mitochondrial markers. The evolutionary history inferred from these phylogenetic patterns suggests that cephalochordates underwent an early divergence into three major lineages, followed by radiation within each genus. The early-diverging positions of Asymmetron and Epigonichthys indicate ancient lineages that have retained key ancestral features, while Branchiostoma appears to represent a more recently diversified clade. Within Branchiostoma, the phylogenetic structure implies that the Indo-West Pacific taxa (B. belcheri, B. japonicum, and B. malayanum) arose from more recent divergence events, potentially driven by historical biogeographic barriers, ecological gradients, or localized adaptation. Importantly, the evolutionary distinctiveness of B. malayanum is further supported by its relatively low intraspecific variability in mitochondrial sequences, suggesting a phase of evolutionary stasis or the action of stabilizing selection. At the same time, its clear separation from congeners points to a long-standing, independently evolving lineage. These findings not only refine our understanding of B. malayanum’s taxonomic placement but also contribute to a broader understanding of cephalochordate evolution, particularly the dynamics of divergence, speciation, and lineage sorting in early chordates20. Our results demonstrate that mitochondrial genomes provide robust phylogenetic resolution among amphioxus taxa and support the continued use of mitogenomic data in resolving deep evolutionary relationships in early-diverging chordates. The integrative framework combining molecular, morphological, and ecological data holds significant promise for clarifying the evolutionary history of amphioxus and illuminating the origins of vertebrate traits.

The discovery and complete mitochondrial genome sequencing of B. malayanum from the Pearl River Estuary significantly extend the known geographic range of this species, which was previously reported only from Southeast Asia. Its confirmed presence in the South China Sea suggests a broader ecological amplitude than previously recognized and raises the possibility that historical dispersal or vicariance events, likely driven by sea-level fluctuations and plate tectonic activity in the Indo-Pacific, contributed to its current distribution. The unique environmental conditions of the Pearl River Estuary—characterized by fluctuating salinity, high sedimentation, and anthropogenic disturbance—present potential selective pressures that may have shaped local adaptation in B. malayanum. The species’ persistence in this estuarine habitat implies underlying physiological or behavioral adaptations that remain to be elucidated. Future research should also aim to expand mitogenomic sampling across Branchiostomatidae, especially in understudied regions such as the eastern Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the western Pacific islands. Population-level mitogenomic studies of B. malayanum across multiple estuarine systems in Southeast Asia would offer valuable insights into gene flow, historical demography, and potential local adaptation, and could reveal cryptic population structure or incipient speciation. Such research efforts are not only important for evolutionary biology but are also critical for conservation. Amphioxus habitats, particularly in estuarine and coastal zones, are increasingly threatened by habitat degradation, pollution, and climate change. Understanding the evolutionary distinctiveness and adaptive capacity of species like B. malayanum is essential for developing informed conservation strategies and preserving the phylogenetic diversity of early-diverging chordates.

Conclusion

This study provides the first complete mitochondrial genome and a detailed comparative analysis of B. malayanum, offering new insights into its taxonomy, mitogenomic structure, and evolutionary relationships within Branchiostomatidae. The mitogenome of B. malayanum displays conserved features typical of cephalochordates, including gene order, strand asymmetry, and codon usage patterns, reflecting strong evolutionary constraints on mitochondrial function. Morphological examination revealed a combination of conserved and variable traits, with developmental allometry affecting external body proportions but not segmental counts. These results emphasize the limitations of morphology alone in amphioxus taxonomy and support the use of integrative approaches. Comparative genetic analyses based on COX1, Cytb, 12 S rRNA, and 16 S rRNA confirmed high intergeneric divergence among Branchiostoma, Asymmetron, and Epigonichthys, and supported the species-level distinctiveness of B. malayanum within its genus. Phylogenetic reconstructions consistently positioned B. malayanum alongside B. belcheri and B. japonicum, forming a well-supported clade distinct from other Branchiostoma lineages. The evolutionary history inferred from mitochondrial data suggests that B. malayanum has undergone independent divergence, likely shaped by its regional distribution in the South China Sea. These findings underscore the importance of mitogenomic data in resolving cryptic diversity and reconstructing lineage relationships in early-diverging chordates. In sum, this study advances our understanding of amphioxus evolution and provides a valuable genomic resource for future phylogenetic and comparative genomic studies in cephalochordates.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Specimens of B. malayanum were collected from the Pearl River Estuary in the South China Sea (22° 32′ N, 114° 28′ E) during a field survey conducted from May 5 to 7, 2024. Bottom sediment was collected from a 25 cm × 25 cm quadrat underwater by divers using a self-fabricated 316 stainless steel sampling tool and transferred into a nylon mesh bag (mesh size: 0.5 mm). Onshore, the sediment was washed through a 0.18 mm mesh sieve, and Branchiostomatidae specimens were hand-picked and immediately preserved in 95% ethanol. During transport, all samples were temporarily stored in an ice-filled cold box. Upon arrival at the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Fishery Ecology and Environment, Branchiostomatidae samples were refrigerated at 4 °C, while sediment samples were frozen at − 20 °C for subsequent analyses.

Morphological examinations

The morphological traits of B. malayanum were categorized into two groups: counting traits and measuring traits. Measurement of counting traits: Individuals of B. malayanum were placed under a dissecting microscope equipped with a light source. The following traits were visually counted: the number of myotomes anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), as well as the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal regions (NFCD, NFCP). Measurement of measuring traits: B. malayanum individuals were positioned flat in a petri dish. Their total length (TL), body height (BH), caudal fin height (CFH), rostral fin length (RFL), and rostral fin height (RFH) were measured using a vernier caliper. Additionally, under a dissecting microscope with a light source and an ocular micrometer, the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA) were measured, along with the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF).

The morphological traits of the B. malayanum, including total length (TL), body height (BH), rostral fin length (RFL), rostral fin height (RFH), the lengths of the segments anterior to the ventral pore (LSAVP), from the ventral pore to the anus (LVPA), and posterior to the anus (LPA), the lengths of the upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin (LUCF and LLCF), caudal fin height (CFH), the number of myotomes anterior to the ventral pore (NMAVP), between the ventral pore and the anus (NMVPA), and posterior to the anus (NMPA), as well as the total number of myotomes (TNM) and the number of fin chambers in the dorsal and preanal (NFCD, NFCP) were log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution. The mean values and standard deviations of these morphological traits were calculated. The coefficient of variation (CV) was used to quantify the spatial variation of the mean values of each trait, with the formula: Coefficient of Variation (CV) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100%. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the mean values of the morphological traits of the B. malayanum. Allometric relationships were used to describe the relative growth rates of different traits in B. malayanum. The allometric equation Y = aXb was employed to fit the allometric relationships between total length (TL) and other morphological traits. By taking the logarithm of both sides of the equation, we obtained ln(Y) = ln(a) + b ln(X), where ln(a) is the allometric constant and b is the allometric coefficient. When b = 1.0, the dependent variable (y) and the independent variable (x) exhibit isometric growth. When b > 1.0 or b < 1.0, an allometric relationship is indicated.

DNA extraction, sequencing and annotation

Genomic DNA was extracted from the muscle tissue of a B. malayanum specimen using the TIANamp Marine Animals DNA Kit (TIANGEN, China). The specimen and the extracted DNA are deposited at the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Fishery Ecology and Environment (https://www.southchinafish.ac.cn/english.htm, Lei Xu, xulei@scsfri.ac.cn) under the voucher number SCS2024-S07-140. The sequencing library was prepared using the Illumina TruSeq™ Nano DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The library was loaded onto the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform for paired-end (PE) 2 × 150 bp sequencing at Jierui Biotech (Guangzhou, China). Raw reads were checked using FastQC v.0.12.0 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Quality trimming and filtering were conducted using FASTP version 0.23.442. Reads with more than 5% unknown nucleotides, low-quality reads (more than 50% of bases with a Q-value ≤ 20), and all unpaired reads were removed. The filtered data were assembled using MitoFinder version 1.4.143 with default settings, utilizing the uploaded COX1 sequence (GenBank: AB248231) as a reference. The mitochondrial genome was annotated using the MITOS WebServer and subsequently verified through BLAST analysis44. Transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were identified using tRNAScan-SE version 1.21 on its web-based platform, with default parameters and the genetic code set to “Mito/chloroplast” to reflect the mitochondrial origin of the sequences45. The mitochondrial genome of the species was visualized based on assembly and annotation data, with a graphical map generated using the GCView Server to clearly represent the genomic features46. Nucleotide composition skewness was assessed using the formulas: \(\:\text{A}/\text{T}-\text{s}\text{k}\text{e}\text{w}=\frac{\text{A}-T}{\text{A}+T}\) and \(\:\text{G}/\text{C}-\text{s}\text{k}\text{e}\text{w}=\frac{\text{G}-C}{\text{G}+C}\) 36. Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) for the 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) was calculated using MEGA version 6.0 47. This analysis offers valuable insights into codon usage bias, which is critical for understanding the genetic coding strategies and evolutionary dynamics of the mitochondrial genome. To quantify genetic divergence among the three extant amphioxus genera—Asymmetron, Branchiostoma, and Epigonichthys—we calculated pairwise evolutionary distances using the Kimura two-parameter (K2P) model. Median percentage values were estimated for both intra- and inter-generic comparisons. The analysis was based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, COX1 (cytochrome c oxidase subunit I) and Cytb (cytochrome b), along with two mitochondrial ribosomal RNA genes, 12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA. Molecular evolutionary rates were calibrated under a strict molecular clock assumption. Pairwise distance analyses, rather than tree-based phylogenetic reconstruction, were performed to evaluate genetic differentiation using the Kimura two-parameter model in MEGA version 6.0 47, with branch support evaluated through 10,000 nonparametric bootstrap replicates. Standard errors of the K2P distances were computed based on this resampling framework to ensure the statistical robustness of the divergence estimates.

Phylogenetic analysis

Protein-coding genes were aligned using MAFFT version 7 implemented in PhyloSuite under default parameters with codon alignment mode48. A total of ten mitochondrial genomes from species within the family Branchiostomatidae were retrieved from the NCBI database and analyzed to infer phylogenetic relationships, with Ciona intestinalis (accession number AM292218) designated as the outgroup (Table S1). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using PhyloSuite version 1.2.149 incorporating both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) approaches. ML phylogenies were reconstructed with IQ-TREE50 under an edge-linked partition model, utilizing 5000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates and the Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) to evaluate branch support51. BI analyses were conducted with MrBayes version 3.2.652 under a partitioned model framework, consisting of two parallel runs for 10,000 generations. The first 25% of sampled trees were discarded as burn-in to ensure convergence and reliability of the posterior probability estimates.

Data availability

The genome sequence data supporting the findings on Branchiostoma malayanum are publicly accessible in GenBank (NCBI) at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] under accession number PV546308.

References

Feng, Y., Li, J. & Xu, A. In Amphioxus Immunity (ed. Xu, A.) 1–13 (Academic, 2016).

Bertrand, S. & Escriva, H. Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: amphioxus. Development 138, 4819–4830. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.066720 (2011).

Nordström, K. J. V., Fredriksson, R. & Schiöth, H. B. The amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae) genome contains a highly diversified set of G protein-coupled receptors. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-9 (2008).

Takatori, N. et al. Comprehensive survey and classification of homeobox genes in the genome of amphioxus, Branchiostoma Floridae. Dev. Genes Evol. 218 (11–12), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-008-0245-9 (2008).

Holland, L. Z. et al. The amphioxus genome illuminates vertebrate origins and cephalochordate biology. Genome Res. 18 (7), 1100–1111. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.073676.107 (2008).

Putnam, N. H. et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature 453 (7198), 1064–1071. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06967 (2008).

Schubert, M., Escriva, H., Xavier-Neto, J. & Laudet, V. Amphioxus and tunicates as evolutionary model systems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.009 (2006).

Peachey, L. D. Structure of the longitudinal body muscles of amphioxus. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 10, 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.10.4.159 (1961).

Poss, S. G. & Boschung, H. T. Lancelets (Cephalochordata: Branchiostomatodae): how many species are valid? Isr. J. Zool. 42, S13–S66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00212210.1996.10688872 (1996).

Wicht, H. & Lacalli, T. C. The nervous system of amphioxus: structure, development, and evolutionary significance. Can. J. Zool. 83, 122–150. https://doi.org/10.1139/z04-163 (2005).

Bertrand, S. et al. The ontology of the amphioxus anatomy and life cycle (AMPHX). Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 668025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fce11.2021.668025 (2021).

D’Aniello, S., Bertrand, S. & Escriva, H. Amphioxus as a model to study the evolution of development in chordates. eLife 12, e87028. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.87028 (2023).

Stokes, M. Larval settlement, post-settlement growth and secondary production of the Florida lancelet (= amphioxus) Branchiostomafloridae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 130, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps130071 (1996).

Guarneri, P. et al. Amphioxus (Branchiostoma lanceolatum) in the North Adriatic Sea: ecological observations and spawning behavior. Integr. Zool. 20(2), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12846 (2025).

Chen, Y., Cheung, S. G. & Shin, P. K. The diet of amphioxus in subtropical Hong Kong as indicated by fatty acid and stable isotopic analyses. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U K. 88, 1487–1491. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315408001951 (2008).

Ruppert, E. E., Nash, T. R. & Smith, A. J. The size range of suspended particles trapped and ingested by the filter-feeding lancelet Branchiostoma Floridae (Cephalochordata: Acrania). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U K. 80, 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315499001903 (2000).

Nohara, M., Nishida, M., Manthacitra, V. & Nishikawa, T. Ancient phylogenetic separation between Pacific and Atlantic cephalochordates as revealed by mitochondrial genome analysis. Zool. Sci. 21, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.21.203 (2004).

Kon, T., Nohara, M., Nishida, M., Sterrer, W. & Nishikawa, T. Hidden ancient diversification in the circumtropical lancelet asymmetron Lucayanum complex. Mar. Biol. 149, 875–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-006-0271-y (2006).

Naylor, G. J. P., Brown, W. M. & Amphioxus Mitochondrial, D. N. A. Chordate phylogeny, and the limits of inference based on comparisons of sequences. Syst. Biol. 47, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/106351598261030 (1998).

Zhang, O. L. et al. A phylogenomic framework and divergence history of cephalochordata amphioxus. Front. Physiol. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01833 (2018).

Zhong, J., Zhang, Q., Xu, Q., Schubert, M. & Wang, V. L. Y. Complete mitochondrial genomes defining two distinct lancelet species in the West Pacific ocean. Mar. Biol. Res. 5, 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000802430817 (2009).

Zhang, Q. J., Zhong, J., Fang, S. H. & Wang, Y. Q. Branchiostoma Japonicum and B. belcheri are distinct lancelets (Cephalochordata) in Xiamen waters in China. Zool. Sci. 23, 573–579. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.23.573 (2006).

Yuan, W., Wang, J., Lin, Q., Wang, C. & Sun, J. The distribution and habitat use of Branchiostoma belcheri at the mouth of Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao in autumn. Biodivers. Sci. 19, 470–475. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1003.2011.06260 (2011).

Henmi, Y. & Yamaguchi, T. Biology of the Amphioxus, Branchiostoma belcheri in the Ariake Sea, Japan I. Population structure and growth. Zool. Sci. 20, 897–906. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.20.897 (2003).

Lin, H. C., Chen, J. P., Chan, B. K. K. & Shao, K. T. The interplay of sediment characteristics, depth, water temperature, and ocean currents shaping the biogeography of lancelets (Subphylum Cephalochordata) in the NW Pacific waters. Mar. Ecol. 36, 780–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12183 (2015).

Richardson, B. J. & McKenzie, A. M. Taxonomy and distribution of Australian cephalochordates (Chordata: Cephalochordata). Invertebr Syst. 8, 1443–1459. https://doi.org/10.1071/IT9941443 (1994).

Au, M. F. F. et al. Spatial distribution, abundance, seasonality and environmental relationship of amphioxus in subtropical Hong Kong waters. Reg. Stud. Ar: Sci. 57, 102726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2022.102726 (2023).

Chen, Y., Cheung, S. G., Kong, R. Y. C. & Shin, P. K. Morphological and molecular comparisons of dominant amphioxus populations in the China seas. Mar. Biol. 153, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-007-0797-7 (2007).

Sun, C. H., Lu, C. H. & Wang, Z. J. Comparison and phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial genomes of synodontis eupterus and synodontis polli. Sci. Rep. 14, 15393. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65809-4 (2024).

Bernt, M., Braband, A., Schierwater, B. & Stadler, P. F. Genetic aspects of mitochondrial genome evolution. Mol. Phylogen Evol. 69, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.10.020 (2013).

Kawashima, Y. et al. The complete mitochondrial genomes of deep-sea squid (Bathyteuthis abyssicola), bob-tail squid (Semirossia patagonica) and four giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama, S. latimanus, S. lycidas and S. pharaonis), and their application to the phylogenetic analysis of decapodiformes. Mol. Phylogen Evol. 69, 980–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.007 (2013).

Duchene, S. et al. Marine turtle mitogenome phylogenetics and evolution. Mol. Phylogen Evol. 65 (1), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.06.010 (2012).

Boore, J. L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1767–1780. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.8.1767 (1999).

Lavrov, D. V., Boore, J. L. & Brown, W. M. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the horseshoe crab limulus polyphemus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026360 (2000).

Saccone, C., De Giorgi, C., Gissi, C., Pesole, G. & Reyes, A. Evolutionary genomics in metazoa: the mitochondrial DNA as a model system. Gene 238, 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00270-X (1999).

Perna, N. T. & Kocher, T. D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 41, 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00186547 (1995).

Hassanin, A., Léger, N. & Deutsch, J. Evidence for multiple reversals of asymmetric mutational constraints during the evolution of the mitochondrial genome of Metazoa, and consequences for phylogenetic inferences. Syst. Biol. 54, 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150590947843 (2005).

Spruyt, N., Delarbre, C., Gachelin, G. & Laudet, V. Complete sequence of the amphioxus (Branchiostoma lanceolatum) mitochondrial genome: relations to vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3279–3285. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/26.13.3279 (1998).

Sharp, P. M., Stenico, M., Peden, J. F. & Lloyd, A. T. Codon usage: mutational bias, translational selection, or both? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 21, 835–841. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0210835 (1993).

Igawa, T. et al. Evolutionary history of the extant amphioxus lineage with shallow-branching diversification. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 1157. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00786-5 (2017).

Brasó-Vives, M. et al. Parallel evolution of amphioxus and vertebrate small-scale gene duplications. Genome Biol. 23 (1), 243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02808-6 (2022).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Allio, R. et al. Efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20 (4), 892–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13160 (2020).

Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: improved de Novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogen Evol. 69 (2), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023 (2013).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997).

Grant, J. R. & Stothard, P. The CGView server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W181–W184. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn179 (2008).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst197 (2013).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Zhang, D. et al. An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20 (1), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13096 (2020).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating Maximum-Likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300 (2015).

Li, X. R., Sun, C. H., Zhan, Y. J., Jia, S. X. & Lu, C. H. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Nannostomus Eques and comparative analysis with Nannostomus beckfordi. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 300, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-024-02212-8 (2024).

Ronguist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61 (3), 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys029 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Zhe Zhang, Dr. Yongbao Zhang and Dr. Fei Tian for field work and Yubin Zhou from Jierui Biotech Company for his invaluable assistance with data analysis. We thank all colleagues and students for their help with sampling.

Funding

This research was supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation [2022B1515250005], Investigation and Evaluation System Construction of Aquatic Biodiversity in Shenzhen coastal waters [NO. SYF[2022]40], In-situ monitoring of benthic communities in typical nearshore habitats of Shenzhen[NO. SYF[2023]46], the foundation of Guangdong Provincial Observation and Research Station for Coastal Upwelling Ecosystem [CUE202305] and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS [N0.2023TD16].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X. and Y.L. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, and wrote the original draft; Q.T. contributed to software and methodology; H.C. and Z.T. conducted investigations, prepared samples, and carried out experiments; P.H., J.N., L.W., S.L. and D.H. participated in the investigation, reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.J. and F.D. supervised the study, conceptualized the research, developed software, and secured funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Li, Y., Tang, Q. et al. Morphological characterization, mitochondrial genome assembly, and phylogenetic reconstruction of Branchiostoma malayanum within Branchiostomatidae. Sci Rep 15, 44393 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28029-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28029-y