Abstract

Stunting affects 149.2 million children globally, with Rwanda experiencing 33% prevalence among children under five years. Poor infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices driven by maternal knowledge gaps exacerbate this challenge. Limited nationally representative data exist examining the comprehensive relationships between maternal knowledge and feeding practices in Rwanda. This study assessed mothers’ and caregivers’ knowledge of stunting causes and consequences and their association with IYCF practices. A cross-sectional study among 2286 mothers and caregivers across 10 districts assessed knowledge of stunting causes (19 items), understanding of consequences (12 items), and IYCF practices (12 items) using WHO/UNICEF guidelines. Three-stage stratified cluster sampling ensured national representativeness. Multivariable logistic regression identified factors associated with inadequate IYCF practices. Among participants (99.0% response rate), 46.4% had low knowledge of stunting causes, particularly infection-related factors. Additionally, 43.5% showed an inappropriate understanding of consequences, especially developmental impacts. IYCF practices were suboptimal: 60.5% demonstrated inadequate practices, and only 29.6% achieved a minimum acceptable diet. Significant predictors included rural residence (AOR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.95–2.91), no formal education (AOR = 4.36, 95% CI 3.04–6.26), young maternal age (AOR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.05–1.85), widowhood (AOR = 4.94, 95% CI 2.28–10.72), and lower socioeconomic status (AOR = 1.59–1.60, 95% CI 1.28–2.20). Low knowledge increased odds 2.43-fold (95% CI 1.81–3.27), while poor understanding increased odds 2.31-fold (95% CI 1.85–2.89) of inadequate practices. Among caregivers of stunted children, substantial knowledge gaps regarding stunting causes and consequences persist, particularly among vulnerable rural populations. The strong associations between maternal knowledge deficits and inadequate feeding practices provide compelling evidence for targeted health and nutrition education interventions addressing specific knowledge gaps, combined with structural support to reduce childhood stunting in Rwanda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stunting, defined as height-for-age below two standard deviations from the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards, represents a critical global public health challenge affecting approximately 149.2 million children under five years worldwide1. This condition extends far beyond physical growth impairment, significantly compromising cognitive development, educational attainment, and long-term economic productivity, making its prevention a cornerstone of sustainable development initiatives globally2. The persistent burden of stunting, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where prevalence remains highest at 32%, underscores the urgent need for evidence-based interventions targeting modifiable risk factors during the critical window of opportunity in early childhood. Understanding the determinants of stunting becomes even more critical when considering that affected children face lifelong consequences, including reduced learning capacity, increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, and diminished work productivity in adulthood, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty and malnutrition3.

Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices during the first 1000 days of life, from conception through the child’s second birthday, represent the critical and irreversible window for stunting prevention. Stunting that occurs during this period results in permanent deficits in linear growth and cognitive development that cannot be fully reversed through later interventions, making prevention during this window essential4. Optimal IYCF practices during this critical period are capable of preventing up to 13% of deaths among children under five years5,6. These practices encompass early initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth, exclusive breastfeeding for six months, timely introduction of nutritionally adequate complementary foods at six months, and continued breastfeeding up to two years and beyond5. However, despite widespread dissemination of these evidence-based recommendations among health professionals and their incorporation into national policies globally, implementation rates remain suboptimal, particularly in resource-constrained settings where the stunting burden is highest2. This implementation gap reflects a complex interplay of factors, including maternal knowledge deficits, socioeconomic constraints, cultural beliefs, and structural barriers that prevent translation of knowledge into practice, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of these relationships to inform effective interventions7.

The irreversible nature of stunting emphasises the urgency of intervention during the first 1000 days. Linear growth faltering and associated brain development impairments that occur during this critical window persist throughout the life course, emphasizing that stunting prevention rather than treatment must be the primary focus. This biological reality makes maternal knowledge and appropriate feeding practices during pregnancy and the first two years of life particularly crucial for breaking the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition8.

Extensive research across low- and middle-income countries has documented significant knowledge deficits among mothers and caregivers regarding stunting causes, consequences, and optimal feeding practices, with these deficits associated with suboptimal child nutritional outcomes through suboptimal feeding behaviors9,10. Studies from Indonesia demonstrate that 70% of mothers possess an inadequate understanding of stunting, often attributing it solely to genetic factors rather than recognizing modifiable nutritional and environmental determinants11. Similar patterns emerge across the region, with South African research revealing that 68% of caregivers cannot identify appropriate complementary foods for children 6–23 months, while Indian studies show only 35% correctly identify key stunting risk factors12,13. These knowledge gaps are associated with practice deficits, as evidenced by Ethiopian research documenting that despite 77% of caregivers demonstrating basic IYCF knowledge, only 32% implement optimal feeding behaviors, indicating substantial barriers beyond awareness9. Intervention studies provide compelling evidence of the relationship between improved maternal knowledge and enhanced practices, with comprehensive maternal education programs demonstrating 40% improvements in children’s nutritional status when knowledge, attitudes, and practices are simultaneously addressed14,15.

The assessment of maternal knowledge, understanding, and practices related to child nutrition has evolved considerably, with recent methodological advances emphasizing comprehensive, multi-dimensional measurement approaches16. Traditional knowledge-practice studies often assessed only awareness of feeding recommendations without distinguishing between surface knowledge and deeper understanding of causal mechanisms and consequences17. Contemporary frameworks recognize that effective behavior change requires both factual knowledge (knowing what to do) and conceptual understanding (knowing why to do it), with both dimensions independently influencing practice adoption18,19. Recent studies have successfully employed composite scoring systems to quantify these multi-dimensional constructs16,17, demonstrating that understanding of stunting consequences predicts feeding practices beyond simple knowledge of causes. This approach aligns with behavioral change theories such as the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior, which posit that perceived severity of health threats (understanding consequences) and perceived benefits of preventive actions (knowledge of causes) jointly influence health behaviors18,19. Our study builds on this evolving measurement framework by separately assessing knowledge of stunting causes, understanding of consequences, and current feeding practices, enabling examination of their independent and combined associations with child nutrition outcomes.

Rwanda presents a particularly compelling case study for examining knowledge-practice relationships in stunting prevention, as the country maintains one of the highest stunting rates globally at 33% among children aged 6–59 months despite significant socio-economic progress and ambitious development goals20. The persistence of high stunting prevalence despite Rwanda’s remarkable economic growth and strong health system infrastructure suggests that factors beyond poverty, including knowledge and behavioral determinants, require urgent attention to accelerate progress toward national nutrition targets. Current IYCF indicators reveal critical deficiencies that may reflect underlying knowledge gaps: while 81% of children under six months receive exclusive breastfeeding, only 22% of children aged 6–23 months achieve minimum acceptable diets, indicating substantial room for improvement in complementary feeding practices21. This study aimed to assess mothers’ and caregivers’ knowledge of stunting causes and consequences and their association with IYCF practices to inform evidence-based interventions for reducing childhood stunting in Rwanda.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a nationally representative cross-sectional design to assess mothers’ and caregivers’ knowledge regarding the root causes and consequences of stunting, and its association with Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices among children under five years in Rwanda. The cross-sectional design was selected to examine associations between knowledge, understanding, and feeding practices across diverse socio-demographic contexts while providing nationally generalizable findings to inform policy development. This design was appropriate for investigating the relationship between maternal knowledge and current feeding practices while enabling identification of factors that could inform targeted interventions to improve child nutrition outcomes.

Study setting

Rwanda is situated in Central Africa, bordered by Uganda to the north, Tanzania to the east, Burundi to the south, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the west. The study was conducted across ten districts representing all provinces of Rwanda, ensuring geographic diversity and national representativeness. The selected districts were: Kicukiro and Gasabo (Kigali City); Bugesera and Rwamagana (Eastern Province); Nyamasheke and Nyabihu (Western Province); Gisagara and Nyamagabe (Southern Province); and Burera and Rulindo (Northern Province). These districts were randomly selected to capture urban–rural diversity and varying socioeconomic conditions characteristic of Rwanda’s demographic distribution. In 2023, the Rwandan economy demonstrated resilience with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of 8.2%, with the services sector contributing 44% of GDP, agriculture contributing 27%, and industry contributing 22% (15). Despite economic progress, 60% of the population lives on less than $1.90 per day, with poverty disproportionately affecting children and their nutritional outcomes22. Rwanda implements a social stratification system called Ubudehe, which categorizes households into different socio-economic groups (Categories I, II, and III) based on income and living standards, serving as a framework for social protection and development programs23. This context of economic growth alongside persistent poverty makes Rwanda an important setting for understanding how maternal knowledge influences child feeding practices across diverse socio-economic conditions.

Study population

The study population comprised mothers and primary caregivers, defined as women aged 15–49 years who were responsible for making feeding decisions and providing daily care for children aged 0–59 months. This included biological mothers, grandmothers, aunts, or other female relatives serving as the main caregiver. While the critical window for stunting prevention is the first 1000 days (conception to age 24 months), we included all children under five years to align with Rwanda’s national stunting monitoring framework and enable assessment of sustained feeding practice patterns across early childhood. However, 55.9% of children in our sample were in the critical 6–23 months age group, ensuring adequate focus on the most intervention-relevant period. Inclusion criteria encompassed women aged 15–49 years serving as primary caregivers for children aged 0–59 months, permanent residents of selected households or overnight visitors present during data collection, and those willing and able to provide informed consent. All eligible participants in selected households were approached, and interviews were scheduled at times convenient for participants to ensure maximum participation. Exclusion criteria included caregivers of children with known congenital conditions affecting growth, households with no children under five years, temporary visitors not involved in child feeding decisions, and individuals unable to communicate in local languages.

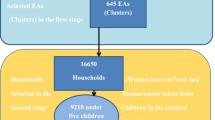

Sampling

A three-stage stratified cluster sampling technique was employed to ensure comprehensive and representative data collection across Rwanda’s diverse geographic and socio-economic contexts. This multistage approach was necessary to achieve national representativeness while maintaining operational feasibility and ensuring all eligible households had a known probability of selection. The sampling strategy was designed to capture variations in knowledge and practices across different administrative levels, from national to local community contexts.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using the Cochran formula for cross-sectional studies with the following parameters24:

The sample size was calculated based on the following formula:

where:

-

\(Z_{1 - \alpha /2}\) is the \(Z\)-score corresponding to the desired confidence level (99% in this case, hence Z = 2.58).

-

\(p\) is the prevalence or the proportion (33% or 0.33).

-

\(d\) is the margin of error (4.01% or 0.0401).

-

\(Deff\) is the design effect (2.0).

-

\(NR\) is the nonresponse rate, expressed here as a fraction of respondents actually completing the survey (0.8 or 80% response rate).

Applying these parameters, the calculated sample size needed to achieve reliable results is n = 2280

The sample size calculation was based on stunting prevalence (33%) rather than IYCF practices for methodological reasons: stunting represents the primary health outcome that IYCF practices aim to prevent, making it the most policy-relevant parameter; reliable national data on specific IYCF practice prevalence was limited at study design; and using stunting prevalence ensures adequate statistical power to detect meaningful associations with feeding practices. Applying these parameters yielded a calculated sample size of 2,280 households, which was achieved through the systematic sampling procedure described below.

Three-Stage cluster sampling procedure

First stage—district selection

Two districts were randomly selected from each of Rwanda’s four provinces plus Kigali City, totaling ten districts. This stratification ensured geographic representativeness across administrative divisions while capturing the urban–rural diversity characteristic of Rwanda’s demographic distribution.

Second stage—village selection

Within each selected district, comprehensive lists of all villages (locally called ‘umudugudu’) were compiled in collaboration with district authorities and Community Health Workers. From these sampling frames, 12 villages per district were randomly selected using probability-proportional-to-size methodology, ensuring equal opportunity for inclusion and maintaining representativeness while minimizing selection bias. This resulted in 120 villages total across all districts.

Third stage—household selection

Within each selected village, eligible households containing at least one child under five years were systematically identified through enumeration conducted with Community Health Workers who possessed detailed knowledge of household composition. From these household sampling frames, 19 households per village were randomly selected using systematic random sampling with random starting points. This level of randomization within clusters was critical to reduce bias and ensure samples accurately reflected population characteristics of interest.

Replacement strategy

Although the initial target was 2,280 households, a total of 2,286 households were ultimately included in the final dataset. During data collection, 38 initially surveyed households provided incomplete responses to critical survey sections (primarily the IYCF practices module) or had eligibility issues discovered during interviews. To ensure the total number of complete and usable responses met the threshold for robust statistical analysis, additional households from the same villages were randomly selected as replacements following the same selection criteria. This adjustment-maintained study integrity and validity while preserving the planned sample size and statistical power. The replacement rate was 1.7%, well within acceptable limits for survey research.

Data collection procedures

Enumerator training and pilot testing

Twenty enumerators with bachelor’s degrees in nutrition, fluency in Kinyarwanda and English, and prior health survey experience were recruited. They completed a five-day training program covering study objectives, questionnaire administration, informed consent procedures, and COVID-19 safety protocols. A pilot study with 50 households in Kayonza District tested questionnaire clarity and comprehension, with minor modifications made based on feedback. Inter-rater reliability assessments achieved acceptable agreement (Cohen’s κ > 0.85)25.

Field data collection

Data collection occurred from November 2021 to January 2022, extended due to COVID-19 restrictions requiring safety protocols. Data collection teams comprised two enumerators and one field supervisor per district. Community Health Workers assisted with household identification but were not present during interviews. Enumerators made up to three visit attempts per household, scheduling interviews flexibly to accommodate participants’ routines. The average interview duration was 45 min. All interviews followed a standardized protocol: introduction and eligibility verification, informed consent in Kinyarwanda, systematic questionnaire administration, immediate response verification, and participant acknowledgment. Responses were recorded electronically using Survey CTO software with standardized coding.

Questionnaire components

The questionnaire was developed by the research team based on WHO/UNICEF guidelines and validated instruments from similar studies, ensuring international comparability and methodological rigor. The questionnaire comprised three main components designed to comprehensively assess knowledge, understanding, and practices related to stunting and IYCF5.

Knowledge Assessment (19 items): Participants were evaluated on their understanding of stunting root causes across multiple domains including maternal factors (nutrition during pregnancy/lactation, birth spacing, education level), environmental factors (sanitation, water supply, food security, hygiene practices), feeding practices (breastfeeding timing/duration, complementary feeding quality), and health factors (infectious diseases, healthcare access). Each correct response received one point (scored as 1), while incorrect or "don’t know" responses received zero points (scored as 0). Total knowledge scores ranged from 0–19, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge of stunting causes.

Understanding Assessment (12 items): Participants were assessed on their comprehension of stunting consequences across temporal domains including immediate consequences (increased morbidity/mortality, healthcare costs), long-term consequences (cognitive impairment, educational underachievement, reduced stature), economic consequences (decreased work capacity/productivity), and intergenerational consequences (perpetuation of malnutrition cycles, reproductive health impacts). Scoring followed the same methodology as knowledge assessment, with total scores ranging from 0 to 12.

IYCF Practice Assessment (12 items): Current and recalled feeding practices were evaluated using WHO/UNICEF standard indicators including breastfeeding practices (initiation timing, exclusivity, duration, frequency), complementary feeding (introduction timing, meal frequency, dietary diversity), food safety and hygiene (pre-lacteal feeding, food preparation), and responsive feeding (feeding during illness, portion sizes). Each appropriate practice was scored as 1, with total scores ranging from 0 to 125.

Quality control and data management

Multiple quality assurance measures were implemented throughout data collection: (1) daily briefings between field supervisors and enumerators to discuss challenges and ensure protocol adherence; (2) random spot-checks by supervisors on 10% of interviews to verify data quality and proper procedures; (3) immediate review of completed questionnaires by supervisors before leaving each village, with incomplete or inconsistent questionnaires returned to enumerators for same-day correction or re-interview when necessary; (4) weekly team meetings to address emerging issues and reinforce best practices. Data were double-entered by independent data entry clerks and cross-checked for accuracy. Range checks and logical consistency checks were performed to identify and correct data entry errors. Missing values were coded systematically, and patterns of missingness were analyzed to assess potential bias.

Variable definition and coding

All IYCF indicators were computed following WHO/UNICEF standard definitions and age-specific denominators as outlined in the 2021 guidelines5. The following indicators were calculated:

-

1.

Early initiation of breastfeeding: Proportion of children born in the last 24 months who were put to the breast within one hour of birth. Denominator: All children aged 0–23 months.

-

2.

Exclusive breastfeeding under 6 months: Proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received only breast milk during the previous day. Denominator: Infants aged 0–5 months.

-

3.

Continued breastfeeding at 1 year: Proportion of children 12–15 months of age who received breast milk during the previous day. Denominator: Children aged 12–15 months.

-

4.

Continued breastfeeding at 2 years: Proportion of children 20–23 months of age who received breast milk during the previous day. Denominator: Children aged 20–23 months.

-

5.

Introduction of solid, semi-solid or soft foods: Proportion of infants 6–8 months of age who received solid, semi-solid or soft foods during the previous day. Denominator: Infants aged 6–8 months.

-

6.

Minimum dietary diversity (MDD): Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who received foods from 5 or more out of 8 defined food groups during the previous day. The eight food groups are: (1) breast milk; (2) grains, roots, and tubers; (3) legumes and nuts; (4) dairy products; (5) flesh foods; (6) eggs; (7) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; (8) other fruits and vegetables. Denominator: Children aged 6–23 months.

-

7.

Minimum meal frequency (MMF): Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who received solid, semi-solid, or soft foods the minimum number of times or more during the previous day. The minimum is defined as:

-

2 times for breastfed infants 6-8 months

-

3 times for breastfed children 9–23 months

-

4 times for non-breastfed children 6–23 months

Denominator: Children aged 6–23 months.

-

-

8.

Minimum acceptable diet (MAD): Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who received a minimum acceptable diet during the previous day. For breastfed children: those who had at least the minimum dietary diversity AND the minimum meal frequency. For non-breastfed children: those who received at least 2 milk feedings AND had at least the minimum dietary diversity (excluding milk feeds) AND the minimum meal frequency. Denominator: Children aged 6–23 months.

-

9.

Consumption of iron-rich or iron-fortified foods: Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who received an iron-rich food or a food that was specially designed for infants and young children and was fortified with iron, or a food that was fortified in the home with a product that included iron during the previous day. Denominator: Children aged 6–23 months.

-

10.

Zero vegetable or fruit consumption: Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who did not consume any vegetables or fruits during the previous day. Denominator: Children aged 6–23 months.

For children aged 24–59 months, recalled breastfeeding practices (initiation timing, duration, exclusivity) were assessed retrospectively, while current feeding practices were evaluated using adapted indicators focusing on dietary diversity and meal frequency appropriate for older children. The composite IYCF practice score encompassed both age-appropriate indicators for younger children (0–23 months) and recalled/current practices for older children (24–59 months), with each indicator weighted equally in the final score calculation.

Knowledge and Understanding Scores

Raw scores were calculated by summing correct responses for each domain. For analytical purposes, participants were categorized using mean-based cutoff points derived from the sample distribution26,27. Scores above the sample mean were classified as "appropriate knowledge/understanding" (coded as 1), while scores below the mean were classified as "low knowledge/inappropriate understanding" (coded as 0).

Knowledge cutoff point

The sample mean for knowledge scores was 10.2 out of 19 possible points. Participants scoring ≥ 11 were classified as having "appropriate knowledge," while those scoring ≤ 10 were classified as having "low knowledge."

Understanding cutoff point

The sample mean for understanding scores was 6.8 out of 12 possible points. Participants scoring ≥ 7 were classified as having "appropriate understanding," while those scoring ≤ 6 were classified as having "inappropriate understanding."

IYCF practice scores

Using similar methodology, the sample mean for IYCF practice scores was 7.1 out of 12 possible points. Participants scoring ≥ 8 were classified as having "adequate IYCF practices," while those scoring ≤ 7 were classified as having "inadequate IYCF practices."

Justification for mean-based cutoffs

The use of sample mean-based cutoff points for categorizing knowledge, understanding, and practices was chosen for several methodological reasons. First, universally validated thresholds for ‘adequate’ maternal knowledge of stunting causes or ‘appropriate’ understanding of consequences do not currently exist in the literature, as stunting knowledge measurement remains an evolving field. Second, mean-based categorization enables identification of relative deficits within the study population, which is appropriate for identifying intervention targets in a specific context. Third, this approach has precedent in nutritional epidemiology research where population-specific cutpoints enable meaningful analysis when external standards are lacking26,27. However, we acknowledge this limitation and recognize that these cutoffs may not reflect absolute competency thresholds or clinical significance. Future research should focus on developing and validating standardized cutoff scores linked to child growth outcomes to enable consistent classification across studies and settings. Despite this limitation, our cutoffs demonstrated good discriminant validity, successfully distinguishing groups with expected differences in practices and showing strong associations with the outcome variable.

Comprehensive package

This composite variable required participant to score above the mean on both knowledge AND understanding components simultaneously to be classified as having "comprehensive appropriate knowledge and understanding" (coded as 1), otherwise classified as "incomplete knowledge and understanding" (coded as 0)28,29.

Scale internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency: Knowledge scale (α = 0.78), Understanding scale (α = 0.74), and IYCF Practice scale (α = 0.82), all indicating acceptable internal consistency for research purposes30,31.

Scale validity

In addition to reliability assessment, we evaluated construct validity of our knowledge, understanding, and practice scales through multiple approaches32,33:

-

1.

Content validity: All scale items were derived from WHO/UNICEF standard IYCF guidelines and validated instruments from prior research, ensuring coverage of relevant domains. A panel of three nutrition experts from the University of Rwanda School of Public Health reviewed all items for relevance and clarity, with a content validity index (CVI) of 0.89 achieved32,33.

-

2.

Convergent validity: The knowledge and understanding scales demonstrated moderate positive correlation (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), supporting theoretical expectations that these constructs would be related but distinct32,33.

-

3.

Known-Groups Validity: The scales successfully discriminated between groups expected to differ in knowledge and practices. Mothers with secondary/higher education scored significantly higher on knowledge (mean = 12.4 ± 2.8) compared to those with no education (mean = 7.8 ± 3.2), t = 14.7, p < 0.001. Similarly, urban residents demonstrated better practices (mean = 8.2 ± 2.1) than rural residents (mean = 6.5 ± 2.4), t = 12.3, p < 0.001, consistent with established health disparities32,33.

-

4.

Criterion validity: IYCF practice scores showed expected associations with child nutritional status in a subsample analysis, with adequate practices associated with lower stunting odds, supporting criterion-related validity32,33.

These validity assessments, combined with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α: 0.74–0.82), provide confidence in the psychometric properties of our measurement instruments.

Sociodemographic variables

Residence of respondent

Whether the respondent is from an urban or rural area.

Religion

Religious affiliation of mothers and caregivers, categorized as Christian (including Catholic, Protestant, and Adventist denominations) or Muslim.

Education of mother

This variable represents the highest level of education achieved by the child’s mother and is categorized into three groups: no education, primary education, secondary education/higher education.

Occupation

The profession of the mother or caregiver at the time of the study, categorized as farmer, merchant, housewife, or employee.

Ubudehe category (wealth index)

Rwanda’s community-based socioeconomic classification system that categorizes households into three levels based on income, assets, and living standards (31):

-

Category I (Lowest): Households living in extreme poverty, characterized by food insecurity, lack of permanent shelter, inability to afford basic health insurance, and often headed by vulnerable individuals (orphans, elderly, persons with disabilities). These households require comprehensive social assistance.

-

Category II (Middle): Households with limited resources but able to meet basic needs inconsistently. They typically have subsistence farming income, basic shelter, but face periodic food insecurity and limited savings. These households benefit from targeted support programs.

-

Category III (Highest): Relatively well-off households with stable income sources, adequate housing, consistent food security, and ability to save. These include salaried workers, successful business owners, and commercial farmers.

This classification is conducted through participatory community meetings and serves as Rwanda’s primary targeting mechanism for social protection programs and subsidized services.

Marital status

The marital status of the mothers/caregivers at the time of the study, categorized as married, divorced or separated, or widowed.

Age group

The age group to which the mothers/caregivers belong, categorized as < 20, 20–29, and > = 30.

Parity

The size of the family, categorized as 1, 2–3, 4–5, or > 5.

Vulnerable populations

For the purposes of this study, vulnerable populations were defined as subgroups experiencing multiple disadvantages that increase risk for poor nutritional outcomes. These included: rural residents, mothers with no formal education, women in the lowest socioeconomic categories (Ubudehe Category I), young mothers (< 20 years), widowed women, and households with higher parity (≥ 4 children). This operational definition was based on established literature documenting elevated stunting risk among these populations and our study’s empirical findings of significantly worse IYCF practices in these groups2,20.

Outcome variable definition

The primary outcome variable was IYCF practices, operationalized as a binary measure of adequacy status. Inadequate IYCF practices were defined as scoring below the sample mean (≤ 7 out of 12 points) on the IYCF practice assessment, while adequate IYCF practices were defined as scoring at or above the sample mean (≥ 8 out of 12 points). This binary outcome (inadequate = 1, adequate = 0) was used in logistic regression analyses to identify factors associated with inadequate feeding practices34. The IYCF practice score encompassed knowledge of appropriate practices, understanding of feeding recommendations, and reported adherence to WHO/UNICEF guidelines, providing a comprehensive measure of feeding adequacy5.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0, with appropriate commands for complex survey data to account for clustering and sampling weights35. Descriptive statistics characterized socio-demographic attributes and feeding practices, with frequencies and proportions calculated for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Missing data patterns were examined and found to be minimal (< 2% for most variables), with complete case analysis employed for all analyses. Univariate analysis used frequency tables and proportions to summarize knowledge, understanding, and IYCF practices.

The outcome variable was inadequate IYCF practices, which quantitatively measured the quality of feeding practices among mothers and caregivers. This binary variable served as the dependent variable in all regression analyses. Independent variables included socio-demographic characteristics (residence, education level, occupation, Ubudehe category, marital status, age, parity, religion) as well as knowledge and understanding scores related to stunting causes and consequences. All variables were coded as categorical variables for analysis36.

Multivariable model building strategy

The multivariable logistic regression model was built using a systematic approach following established guidelines34. Variables were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model based on multiple criteria:

-

1.

Bivariate screening: All independent variables were first assessed through bivariate logistic regression. Variables demonstrating associations with inadequate IYCF practices at p < 0.25 in bivariate analysis were considered candidates for the multivariable model, using a liberal threshold to avoid excluding potentially important confounders34.

-

2.

Theoretical considerations: Variables were also included based on theoretical importance and documented associations with IYCF practices in existing literature, regardless of bivariate significance, to control for known confounders34.

-

3.

Model building process: Variables were entered into the multivariable model in blocks:

-

Block 1: Sociodemographic factors (residence, age, education, marital status, occupation)

-

Block 2: Socioeconomic factors (Ubudehe category, parity)

-

Block 3: Knowledge and understanding factors (knowledge of causes, understanding of consequences)

-

-

4.

Assessment of confounding: Variables were retained in the final model if they: (a) were independently associated with the outcome at p < 0.05, (b) were important confounders (changed other coefficients by > 10% when removed), or (c) were of theoretical importance as established risk factors.

-

5.

Collinearity assessment: Variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated to assess multicollinearity, with VIF < 5 considered acceptable. No significant collinearity was detected (all VIF values < 3.2)36.

-

6.

Model fit assessment: Final model fit was evaluated using34:

-

Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ2 = 7.23, p = 0.51, indicating good fit)

-

Pseudo R2 (0.342, indicating acceptable explanatory power)

-

Area under ROC curve (AUC = 0.78, indicating good discrimination)

-

-

7.

Model diagnostics: Influential observations were identified using dfbeta statistics, and sensitivity analyses excluding potential outliers confirmed result stability.

The final model included all variables shown in Table 6, representing the most parsimonious model that adequately explained the outcome while controlling for important confounders. Bivariate logistic regression identified independent variables showing statistically significant relationships with the outcome variable, using a significance level of p < 0.05. Variables significant in bivariate analysis were included in multivariable logistic regression models to determine factors independently influencing IYCF practices. The significance level for multivariable analysis was set at p ≤ 0.05, with results presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals 34.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (CMHS IRB) of the University of Rwanda (Approval No: 392/CMHS IRB/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection, with participants informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study through secure data storage, removal of personal identifiers, and restricted data access to authorized research personnel only.

Results

Study participation and response rate

A total of 2308 households were contacted across 120 villages in 10 districts of Rwanda. Of these, 2286 households participated in the study, yielding a response rate of 99.0%. Complete and usable responses were obtained from all 2286 participants, with no missing data on key outcome variables. The final analytical sample comprised 2145 biological mothers (93.8%) and 141 other primary caregivers (6.2%), including grandmothers, aunts, and other female relatives responsible for child feeding decisions.

Sociodemographic characteristics of children 5 years, mothers and caregivers

The age distribution of children showed that more than half (55.9%, n = 1,277) were in the critical 6–23 months age window when complementary feeding practices are most crucial for growth. Nearly one-quarter (23.0%, n = 526) were in the exclusive breastfeeding period (0–5 months), while 21.1% (n = 483) were older children aged 24–59 months. This distribution ensured adequate representation across all age categories for age-specific IYCF indicator assessment.

Most participants resided in rural areas (63.8%, n = 1458), had primary education (58.9%, n = 1347), were classified in Ubudehe Category I (47.9%, n = 1,096), aged 30 + years (48.3%, n = 1105), worked as farmers (46.5%, n = 1063) or housewives (37.8%, n = 863), were married (83.5%, n = 1908), Christian (97.9%, n = 2237), and had 2–3 children (45.7%, n = 1,045) as shown in Table 1.

Knowledge of root causes of stunting

The 19-item knowledge assessment (Cronbach’s α = 0.78) revealed substantial knowledge gaps among participants. Participants most frequently recognized feeding insufficient quantities (69.2%, n = 1583), early breastfeeding cessation (59.8%, n = 1366), and infrequent feeding (59.7%, n = 1364) as stunting causes. They moderately recognized low dietary diversity (54.1%, n = 1236) and inadequate illness feeding (53.8%, n = 1229). Critical gaps existed in participants’ recognition of infection-related causes: malaria (25.3%, n = 579), respiratory infections (28.3%, n = 648), and enteric infections (32.1%, n = 734). The knowledge score mean was 10.2 (SD = 3.4) out of 19 points. Using sample mean cutoffs, 46.4% (n = 1061) of participants demonstrated low knowledge while 53.6% (n = 1225) showed appropriate knowledge, as detailed in Table 2.

Understanding of consequences of stunting

The 12-item understanding assessment (Cronbach’s α = 0.74) showed mixed comprehension patterns among participants. Participants demonstrated high recognition of immediate health consequences: increased morbidity (87.0%, n = 1988) and decreased stature (73.3%, n = 1676). They showed moderate understanding of cognitive consequences: decreased cognitive function (57.2%, n = 1308) and diminished learning capacity (47.9%, n = 1096). Critical gaps existed in participants’ understanding of developmental impacts: motor and language development (15.7%, n = 358) and economic implications through increased health expenditure (6.6%, n = 152). The understanding score mean was 6.8 (SD = 2.1) out of 12 points. Overall, 43.5% (n = 994) of participants demonstrated inappropriate understanding, while 56.5% (n = 1292) showed appropriate understanding, as presented in Table 3.

IYCF Indicators by WHO/UNICEF Age categories

Age-disaggregated IYCF indicators revealed mixed adherence to WHO/UNICEF recommendations among participants. Mothers and caregivers achieved early breastfeeding initiation within one hour for only 43.8% of children aged 0–23 months, while exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0–5 months reached 68.4%. They showed strong adherence to continued breastfeeding practices at 92.2% (12–15 months) and 92.5% (20–23 months). Participants introduced complementary foods at 6–8 months for 76.4% of children. However, critical gaps emerged for children aged 6–23 months: only 53.5% of caregivers achieved minimum dietary diversity, 38.2% provided minimum meal frequency, and merely 29.6% met minimum acceptable diet standards. Age-specific meal frequency provided by caregivers remained consistently suboptimal across all subgroups (37.4%-40.4%). Additional concerns included low iron-rich food consumption among children (36.6%), zero vegetable/fruit consumption among 14.8% of children, and bottle feeding practiced by 14.8% of caregivers for children aged 0–23 months. These age-stratified findings highlight the need for targeted interventions addressing complementary feeding practice gaps during the critical 6–23 months window, as presented in Table 4.

IYCF practices among mothers and caregivers

The 12-item IYCF assessment (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) revealed significant practice gaps among participants. Mothers and caregivers showed mixed adherence to breastfeeding practices: 74.8% (n = 1,709) ever breastfed, 68.4% (n = 1,563) exclusively breastfed for six months, but only 34.5% (n = 789) initiated within one hour and 28.5% (n = 651) fed > 10 times daily. Complementary feeding gaps were pronounced among participants: only 21.0% (n = 479) introduced foods at six months, 38.2% (n = 874) provided minimum meal frequency, and 15.2% (n = 348) met age-specific frequency for 6–23 months children. Dietary quality was suboptimal: 53.5% (n = 1,223) of participants achieved minimum dietary diversity, but only 29.6% (n = 677) met minimum acceptable diet standards. The IYCF score mean was 7.1 (SD = 2.3) out of 12 points. Overall, 60.5% (n = 1,383) of mothers and caregivers demonstrated inadequate practices while 39.5% (n = 903) showed adequate practices, as shown in Table 5.

Factors associated with IYCF practices

Multiple logistic regression analysis (Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 = 7.23, p = 0.51; Pseudo R2 = 0.342) identified significant predictors of inadequate IYCF practices among participants. Among geographic factors, rural residence showed the strongest association (AOR = 2.30; 95% CI 1.95–2.91; p < 0.001). Participants’ educational level demonstrated dose–response relationships: no formal education (AOR = 4.36; 95% CI 3.04–6.26; p < 0.001) and primary education (AOR = 2.11; 95% CI 1.55–2.86; p < 0.001) versus secondary/higher education. Among socioeconomic factors, Ubudehe Categories I (AOR = 1.60; 95% CI 1.28–2.00; p < 0.001) and II (AOR = 1.59; 95% CI 1.40–2.20; p < 0.001) versus Category III were associated with higher odds of inadequate practices. Among demographic factors, younger mothers < 20 years (AOR = 1.40; 95% CI 1.05–1.85; p = 0.021), widowed status (AOR = 4.94; 95% CI 2.28–10.72; p < 0.001), and higher parity 4–5 children (AOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.27–2.29; p < 0.001) were significant predictors. Among knowledge factors, low stunting knowledge (AOR = 2.43; 95% CI 2.81–5.49; p = 0.043) and inappropriate understanding of consequences (AOR = 2.31; 95% CI 1.45–2.79; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with inadequate practices, as detailed in Table 6.

Discussion

This nationally representative study of 2,286 mothers and caregivers across Rwanda reveals critical knowledge gaps and suboptimal feeding practices significantly associated with child nutrition outcomes. Our findings demonstrate that 46.4% of participants had low knowledge of stunting causes, 43.5% showed inappropriate understanding of consequences, and 60.5% practiced inadequate IYCF, with only 29.6% of children aged 6–23 months achieving minimum acceptable diet standards.

Substantial knowledge deficits existed among participants regarding stunting etiology, particularly infection-related causes, where awareness ranged from only 25.3% for malaria to 32.1% for enteric infections. These knowledge gaps are particularly concerning given the well-established role of parasitic and bacterial infections in stunting pathogenesis37. Parasitic infections (intestinal helminths and protozoa, including Giardia lamblia) and bacterial pathogens (Escherichia coli, Shigella, Campylobacter) contribute to stunting through nutrient malabsorption, chronic inflammation, and environmental enteric dysfunction38,39,40. In the critical 6–23 months window, when 55.9% of our study children were concentrated, repeated infection episodes are particularly detrimental to linear growth41. Malaria contributes through chronic anemia and metabolic stress42. The infection-nutrition nexus operates bidirectionally, creating a vicious cycle37. Health and nutrition education programs must explicitly address how infections contribute to stunting and emphasize integrated WASH practices43, timely deworming44, and infection prevention strategies42. While participants demonstrated better understanding of feeding-related causes (69.2% for insufficient food quantities), critical gaps persisted in maternal factors (43.7%). These findings align with Indonesian studies showing 70% inadequate knowledge11, but contrast favorably with Asia where unawareness exceeded 72%45.

Participants’ understanding of stunting consequences showed concerning patterns: high awareness of immediate health effects (87.0%) but poor comprehension of long-term developmental impacts37. Limited recognition of motor and language development consequences (15.7%) and economic implications (6.6%) suggests existing programs fail to convey long-term, multifaceted impacts.

Our assessment revealed that participants demonstrated significant departures from WHO/UNICEF guidelines5. While exclusive breastfeeding (68.4%) approached targets, critical gaps emerged in complementary feeding: only 21% introduced foods at six months, 15.2% met age-appropriate meal frequency, and 29.6% achieved minimum acceptable diet20. These findings parallel sub-Saharan African patterns where inadequacies ranged from 21.8% to 67%9,46

Multivariable analysis identified critical determinants34. Rural residence showed the strongest association (AOR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.95–2.91), reflecting limited healthcare access20. Participants’ educational attainment demonstrated a powerful dose–response: no formal education increased odds 4.36-fold, while primary education increased odds 2.11-fold2. Programmatic health and nutrition education interventions offer modifiable pathways for improvement6. Socioeconomic status (Ubudehe categories)23, significantly associated with practices, with lower categories showing 1.6-fold increased odds2.

Vulnerable subgroups emerged: widowed mothers (AOR = 4.94, 95% CI 2.28–10.72) (27), younger mothers < 20 years (AOR = 1.40), and higher parity 4–5 children (AOR = 1.70) (2). An unexpected finding showed divorced/separated mothers had lower odds of inadequate practices (AOR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.26–0.48). This may reflect stronger natal family connections, increased decision-making autonomy, and selection effects46, warranting qualitative investigation.

Strong associations between participants’ knowledge/understanding and their practices (AOR = 2.43 for low knowledge, AOR = 2.31 for poor understanding) provide compelling evidence for education-based interventions34, though knowledge alone is insufficient. This knowledge-practice gap aligns with Ugandan findings of implementation barriers46.

Our study advances methodology by distinguishing between knowledge of causes and understanding of consequences through separate validated scales23,47. This multi-dimensional approach is theoretically important as declarative and explanatory knowledge represent distinct cognitive dimensions28. Knowledge and understanding showed moderate correlation (r = 0.58) while demonstrating independent associations with practices34, supporting frameworks emphasizing both ‘knowing what’ and ‘knowing why’6. Strong psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α: 0.74–0.82; adequate construct validity)30,33 demonstrate feasibility in resource-limited settings, offering a replicable framework for future research.

Our findings strongly support comprehensive Maternal, Infant, and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) programming rather than isolated interventions6. Multiple interconnected gaps, maternal factors (43.7%), infection-related causes (25.3–32.1%), and environmental determinants (41.1–62.9%), demonstrate that single-focus interventions will be insufficient37. Effective stunting reduction requires comprehensive approaches addressing maternal health, food security, WASH, infection control, and women’s empowerment6,43. Rwanda’s community health worker platform provides ideal delivery mechanisms20, ensuring messages address the full spectrum of determinants.

Our findings underscore targeting interventions during the first 1000 days when prevention is still possible37. Given stunting’s irreversibility, health and nutrition education must reach mothers before pregnancy and intensively during the first two years6. The 55.9% of children aged 6–23 months represents the group for whom immediate intervention could prevent irreversible stunting5.

Study strengths include nationally representative design, large sample size providing adequate power34, validated WHO/UNICEF indicators5, comprehensive assessment, and high response rate (99.0%), minimizing bias36. Limitations include cross-sectional design precluding causal inference36, mean-based cutoffs possibly not reflecting clinically meaningful thresholds (18), potential social desirability bias36, and recall bias, particularly for older children (3). Including children up to 59 months rather than restricting to < 24 months increased recall bias and decreased IYCF indicator relevance37, though 55.9% were in the critical 6–23 months window with age-stratified analyses conducted5,20.

Future research should address several priorities. Longitudinal studies tracking knowledge, practices, and child growth outcomes over time would provide stronger evidence for causal relationships and intervention effectiveness. Mixed-methods research incorporating qualitative approaches could illuminate cultural and contextual factors influencing feeding decisions. Intervention trials testing different educational approaches, delivery modalities, and targeting strategies would provide evidence for optimal program design. Economic evaluations could inform resource allocation decisions. Validation of knowledge and practice measurement tools against objective child nutritional outcomes would strengthen future research methodology. Comparative research across different sub-Saharan African contexts could identify generalizable versus context-specific intervention approaches.

Conclusions

This nationally representative study demonstrates that inadequate maternal knowledge and understanding of stunting are significantly associated with suboptimal IYCF practices among caregivers of stunted children in Rwanda. Critical knowledge deficits were identified: 46.4% had low knowledge of causes, 43.5% showed inappropriate understanding of consequences, and 60.5% demonstrated inadequate feeding practices. High-risk populations include rural residents (AOR = 2.30), mothers with no formal education (AOR = 4.36), widowed women (AOR = 4.94), and lower socioeconomic households (AOR = 1.59–1.60). Low knowledge increased inadequate practice odds 2.43-fold, while poor understanding increased odds 2.31-fold. Given stunting’s irreversibility during the first 1000 days, comprehensive Maternal," Infant and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) programming integrating health education with maternal health services, infection prevention, and WASH initiatives is urgently needed, prioritizing identified vulnerable populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMHS:

-

College of medicine and health sciences

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- IYCF:

-

Infant and young child feeding

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MIYCN:

-

Maternal, infant and young child nutrition

- MOH:

-

Ministry of health

- NISR:

-

National institute of statistics of Rwanda

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children’s Fund

- WASH:

-

Water, sanitation, and hygiene

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

UNICEF, WHO, Group WB. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key finding of the 2023 edition. Asia-Pacific Popul J. 2023;24(2):51–78.

Black, R. E. et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382(9890), 427–451 (2013).

Kalinda, C. et al. Leveraging multisectoral approach to understand the determinants of childhood stunting in Rwanda: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 13(1), 1–12 (2024).

Soliman, A. et al. Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: From childho od to adulthood. Acta Biomed. 92(1), 1–12 (2021).

UNICEF. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices [Internet]. Vol. WHA55 A55/, World Health Organization. 2010. 19 p. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44306/9789241599290_eng.pdf?sequence=1%0Ahttp://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596664_eng.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/innocenti.htm%5Cnhttp://innocenti15.net/declaration.

Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost?. Lancet 382(9890), 452–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4 (2013).

Infant and young child feeding [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding

Soliman, A. et al. Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: From childhood to adulthood. Acta Biomed. 92(1), 1–12 (2021).

Geda, N. R. et al. Infant and young child feeding practices in Ethiopia: Analysis of socioeconomic disparities based on nationally representative data. Arch. Public Health. 79(1), 35 (2021).

Prasetyo, Y. B., Permatasari, P. & Susanti, H. D. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children ‘s nutritional status: A systematic review. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy. 17(1), 11 (2023).

Setyawati, V. A. V., Kurniadi, A. & Isworo, S. Improving mother knowledge about stunting by mobile base nutrition education. Wjpmr. 5(4), 60–64 (2019).

Eldah, T. T., Mary, M., Selina, R. N. & Cecilia, M. T. Perceptions of caregivers regarding malnutrition in children under five in rural. Child 9(11), 1784 (2022).

Aguayo, V. M., Nair, R., Badgaiyan, N. & Krishna, V. Determinants of stunting and poor linear growth in children under 2 years of age in India: An in-depth analysis of Maharashtra’s comprehensive nutrition survey. Matern. Child Nutr. 12(2016), 121–140 (2016).

Forh, G., Apprey, C. & Frimpomaa Agyapong, N. A. Nutritional knowledge and practices of mothers/caregivers and its impact on the nutritional status of children 6–59 months in Sefwi Wiawso Municipality, Western-North Region, Ghana. Heliyon. 8(12), e12330 (2022).

Prasetyo, Y. B., Permatasari, P. & Susanti, H. D. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children’s nutritional status: A systematic review. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy. 17(1), 11 (2023).

Masilela, L. N. & Modjadji, P. Child nutrition outcomes and maternal nutrition-related knowledge in rural localities of Mbombela, South Africa. Child 10(8), 1294 (2023).

Gemede, H. F., Ayele, K. & Demisew, M. Maternal knowledge and practices on complementary feeding and associated factors in Sedal District, Western Ethiopia. Food Sci. Nutr. 13(5), e70286 (2025).

Michie, S., West, R., Sheals, K. & Godinho, C. A. Evaluating the effectiveness of behavior change techniques in health-related behavior: A scoping review of methods used. Transl. Behav. Med. 8(2), 212–224 (2018).

UNICEF. The Behavioural Drivers Model. Univ Pennsylvania. 2019;92.

RDHS2019–20. National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), Ministry of Health (MOH), ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2019–20. Kigali, Rwanda, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH, and ICF International; 2021. 2019.

Ngaruye, I. et al. Child stunting prevalence determination at sector level in Rwanda using small area estimation. BMC Nutr. 9(1), 1–8 (2023).

World Bank. Gross domestic product 2018 Gross domestic product 2018. 2023;(July):1–4.

Alexis, H. The challenges and examination of new programme ubudehe 2020 in Rwanda. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 13(05), 287–311 (2023).

Chameides L, Diana DJ, Leopold HB, Heller FA. Cardiovascular diseases. NMS Pediatr 5th Ed. 2012;276–96.

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1), 159–174 (1977).

Sitotaw, B. & Philipos, W. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (kap) on antibiotic use and disposal ways in Sidama Region, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional survey. ScientificWorldJournal. 2023, 8774634 (2023).

Permatasari, T. A. E. & Chadirin, Y. Assessment of undernutrition using the composite index of anthropometric failure (CIAF) and its determinants: A cross-sectional study in the rural area of the Bogor District in Indonesia. BMC Nutr. 8(1), 1–20 (2022).

Hu, F. B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 13(1), 3–9 (2002).

Schulz, C. A., Oluwagbemigun, K. & Nöthlings, U. Advances in dietary pattern analysis in nutritional epidemiology. Eur. J. Nutr. 60(8), 4115–4130 (2021).

Eunseong, C. & Seonghoon, K. Cronbach’s coefficient alpha: Well known but poorly understood. Organ Res. Methods. 18(2), 207–230 (2014).

Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55 (2011).

Kyriazos, T. A. et al. Validation of the flourishing scale (FS), greek version and evaluation of two well-being models. Psychology 09(07), 1789–1813 (2018).

Terwee, C. B. et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 60(1), 34–42 (2007).

Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R. X. Applied Logistic Regression 3rd edn, 1–499 (Wiley, 2013).

Venugopal, S. K. Do systematically important banks pursue low-cost deposits: Insights from a difference-in-differences estimation. Theor. Econ. Lett. 13(05), 1289–1306 (2023).

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology: Third edition. Mod Epidemiol Third Ed. 2011;1–758.

Prendergast, A. J. & Humphrey, J. H. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatr. Int. Child Health. 34(4), 250–265 (2014).

Korpe, P. S. & Petri, W. A. J. Environmental enteropathy: Critical implications of a poorly understood condition. Trends Mol. Med. 18(6), 328–336 (2012).

Checkley, W. et al. Multi-country analysis of the effects of diarrhoea on childhood stunting. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37(4), 816–830 (2008).

Owino, V. et al. Environmental enteric dysfunction and growth failure/stunting in global child health. Pediatrics 138(6), e20160641 (2016).

Keusch, G. T. et al. Implications of acquired environmental enteric dysfunction for growth and stunting in infants and children living in low- and middle-income countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 34(3), 357–364 (2013).

Caulfield, L. E., de Onis, M., Blössner, M. & Black, R. E. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80(1), 193–198 (2004).

Ngure, F. M. et al. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: Making the links. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1308, 118–128 (2014).

Donowitz, J. R. & Petri, W. A. J. Pediatric small intestine bacterial overgrowth in low-income countries. Trends Mol. Med. 21(1), 6–15 (2015).

Guled, R. A. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of mothers/caregivers on infant and young child feeding in Shabelle zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Revel. Sci. 6(2), 42–54 (2016).

Nankumbi, J. & Muliira, J. K. Barriers to infant and child-feeding practices: A qualitative study of primary caregivers in rural Uganda. J. Heal. Popul. Nutr. 33(1), 106–116 (2015).

Ssentongo, P. et al. Association of vitamin A deficiency with early childhood stunting in Uganda: A populationbased cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 15(5), 1–16 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the study participants, community leaders, and local health workers for their cooperation during the data collection process.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. G.A and C.M. conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. G.A contributed to the data analysis. M.M., G.A., F.K.R., and J.C. provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (CMHS IRB) of the University of Rwanda (Approval No: 392/CMHS IRB/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mporanyi, T., Condo, J., Absolomon, G. et al. Influence of maternal knowledge of causes and consequences of stunting on infant and young child feeding practices in Rwanda. Sci Rep 15, 44481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28082-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28082-7