Abstract

The possible contribution of ultrasonography to the prognosis of cervical cancer is still mostly unknown. Clinicopathological information about patients with cervical cancer from 2019 to 2024 was gathered from the database of the Chongqing Medical University Second Affiliated Hospital. A training group comprising 70% of the dataset and a validation cohort comprising 30% were randomly selected. Univariate and multivariate competing risk models were used to identify independent prognostic markers. A nomogram to forecast the probability of death specific to cancer was created based on these variables. ROC curves, area under the curve (AUC), concordance index (C-index), and calibration curves were used to evaluate the nomogram’s accuracy and discriminative power. The training and validation sets were validated independently. 428 individuals with cervical cancer were randomized to be in one of two groups: the training group (n = 296) or the validation group (n = 132). 54.0 months was the average follow-up period (range: 6.0–80.0 months). Advanced age (p = 0.002) and FIGO stages III–IV (p = 0.020) were strongly linked to premature mortality. Moreover, no previous surgery and ultrasound-assessed blood supply and interstitial infiltration were also independently correlated with lesser overall survival. These results led to the development of a nomogram to estimate cancer-specific survival at one, two, and three years. In this work, we created and verified a predictive nomogram for patients with cervical cancer, integrating ultrasonography characteristics into a survival prediction model for the first time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the latest Global Cancer Statistics1,2, cervical cancer ranks fourth among cancers that affect women in terms of both incidence and mortality. Cervical cancer continues to be a major cause of cancer-related mortality in low-income nations, even with the success of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines for prevention and cervical screening tests for early identification3,4,5. It poses a serious public health burden and is a major cause of female death in China, especially in the western regions2,6.

Up until 2018, clinical assessments were the only basis for the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics’ (FIGO) cervical cancer staging system. Nonetheless, that year saw a significant breakthrough when imaging and pathology evaluations were included to the staging criteria7. These days, imaging methods like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET-CT), and ultrasound are essential for treatment planning8. Transvaginal sonography (TVS) is by far the most practical, non-invasive, and reasonably priced of these. The ability to assess lesion size and determine the local extent of cervical cancer has significantly improved due to recent advancements in transvaginal ultrasound resolution. Studies demonstrate that TVS can evaluate local tumor invasion with diagnostic precision comparable to MRI9. Additionally, color Doppler ultrasonography, power Doppler ultrasound, and superb microvascular imaging (SMI) can assess tumor angiogenesis. These approaches can identify highly vascularized tumors associated with pelvic lymph node metastases, lymph-vascular space invasion, and parametrial involvement10,11. The prognosis of patients may be influenced by these acoustic properties, which could provide insights into the biology and behavior of malignancies10.

The FIGO stage, tumor dimensions, histological classification, invasion depth, and pelvic lymph node metastases are variables influencing the prognosis of cervical cancer patients12. Recent research has utilized nomograms to develop prognostic prediction models for cervical cancer13,14,15, although none of these models have incorporated ultrasound features.

Our research seeks to address this gap by developing a distinctive nomogram that assesses the prognosis of cervical cancer by the integration of ultrasound characteristics and supplementary clinical prognostic factors. The utilization of this enhanced predictive tool may yield superior patient outcomes by facilitating more personalized treatment regimens.

Research Questions:

-

1.

How do separate prognostic factors found by ultrasonography in cervical cancer patients change the prediction of their overall survival?

-

2.

How can prognosis accuracy for patients with cervical cancer be improved by including ultrasonography parameters in nomogram-based survival prediction models?

Contributions:

-

Our investigation identified tumor vascularization, extent of cervical invasion, and tumor dimensions, as assessed by ultrasonography, as significant independent prognostic indicators. The characteristics provide crucial insights into tumor behavior and survival rates, improving our understanding of cervical cancer prognosis.

-

The suggested study demonstrates that the integration of ultrasonic properties improves the accuracy, reliability, and feasibility of survival predictions. This integration enables cervical cancer patients in resource-limited regions to have more personalized treatment.

Materials and methods

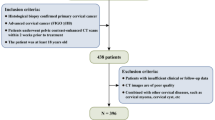

This study aimed to develop a predictive nomogram for survival outcomes to assess the prognostic utility of ultrasonographic data in cervical cancer patients. The approach included clearly delineated steps such as study design, data collection, statistical analysis, and validation of the predictive model. Figure 1A illustrates a workflow diagram depicting the methodologies utilized in the study to evaluate prognostic indicators in patients with cervical cancer. To ensure the relevance of the cases, 428 eligible patients were initially selected from a database and assessed using inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultrasonography and clinicopathological data were subsequently collected, encompassing clinical information, vascular supply, and tumor dimensions. The dataset was then randomly partitioned into two cohorts: 70% allocated for training and 30% designated for validation. The training data underwent univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to identify significant prognostic factors. A nomogram was subsequently developed to predict survival outcomes utilizing this data. Metrics such as the concordance index (C-index), ROC curves, and calibration plots were employed to evaluate the nomogram’s accuracy and reliability.

Incremental predictive and clinical utility metrics were used to assess model performance beyond standard discrimination measures. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were computed at the 36-month horizon to quantify the improvement in predictive accuracy compared with the conventional FIGO staging model. Decision-curve analysis (DCA) was extended to the training, validation, and overall datasets to evaluate the standardized net benefit (NB) across threshold probabilities ranging from 1% to 60%. These analyses compared the nomogram, the FIGO-only model, and “treat-all” and “treat-none” strategies to determine the model’s practical value in guiding clinical decisions under censoring, using inverse probability of censoring weighting (IPCW) methods.

Study population

This research utilized data from 428 individuals diagnosed with cervical cancer between 2019 and 2024 at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. For analysis, ultrasonographic and clinicopathological data were gathered. Eligibility requirements included thorough follow-up records and histological confirmation of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Ages under 18 or over 85, recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer, insufficient clinical data, and the lack of transvaginal ultrasonography within a week prior to therapy were among the exclusion criteria. The Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University authorized this retrospective study, which complied with the Helsinki Declaration’s guidelines. For every participant, informed consent was obtained. A diagram of the study design is shown in Fig. 1B.

Data collection

The following clinicopathological variables were gathered: pathologic type, tumor differentiation, age, lymph node metastasis, cervical interstitial infiltration depth, ultrasonography findings (including lesion size and blood supply status), initial tumor treatment, and FIGO stage. Within a week before therapy, transvaginal ultrasound examinations were performed on all cervical cancer patients using high-resolution ultrasound technology. The cervix, uterus, vagina, bilateral parametrial tissues, and bilateral ovaries were evaluated throughout these tests. Cervical lesions were described as hyperechoic, isoechoic, hypoechoic, or mixed in relation to surrounding tissues. The two largest diameters of the lesion were measured. To assess the distribution of blood flow signals within the cervical lesion and adjacent tissues, color Doppler imaging was employed. Blood-flow patterns were divided into two categories: networks or stripes denoting a rich or adequate blood supply, and spots or short bars denoting an increased but insufficient blood supply. For two years following treatment, patients were followed up every three months; from the third to fifth years, every six months; and annually thereafter.

Statistical analysis

A training group consisting of 296 patients (70%) and a validation group consisting of 132 patients (30%) were randomly selected from among the 428 patients in this study. Baseline characteristics were compared between cohorts using independent t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables (confirmed by Shapiro–Wilk testing) or Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normal distributions, and chi-square tests for categorical variables, with significance set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). For analytical purposes, FIGO stages were categorized as I–II versus III–IV, while baseline characteristics presented the original three-category classification (I, II, and III–IV) for comprehensive demographic reporting. The validation cohort was used for external validation after the prognostic model was created using the training cohort. Potential prognostic factors were first assessed using univariate Cox regression analysis. Variables that showed statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in the multivariate Cox regression model to identify independent predictors of survival, and their effects were measured using hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

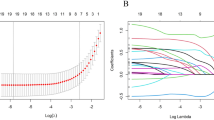

A prognostic nomogram was created to graphically depict the probability of survival at one, two, and three years. Model performance was assessed by the C-index, time-dependent AUC, and calibration plots using bootstrap resampling. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare survival distributions, and the log-rank test was used to assess statistical significance.

To evaluate incremental predictive utility, time-dependent NRI and IDI analyses were performed at 36 months to compare the nomogram with the FIGO-only model. In addition, DCA was carried out not only for the validation cohort but also for the training and overall datasets to assess standardized NB across clinically relevant threshold probabilities. Finally, to enhance clinical interpretability, patients were stratified into low-, medium-, and high-risk groups based on tertiles of the nomogram’s linear predictor (LP) derived from the training cohort. The same cut-points were applied to the validation and overall datasets. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were conducted for each risk group, with log-rank tests comparing group-specific survival probabilities at the 36-month horizon. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2, and a two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristic

This study involved 428 patients with cervical cancer. The baseline characteristics of the research population are summarized in Table 1. All patients had a mean follow-up time of 54.0 months (range: 6.0–80.0 months). No significant differences in patient characteristics were observed between the two cohorts (p > 0.05).

Prognostic factors analysis

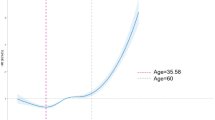

Cox regression analysis was used to assess potential prognostic markers in patients with cervical cancer. Both advanced age (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.06, p = 0.002) and FIGO stage III–IV compared to FIGO stage I–II (HR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.17–5.99, p = 0.020) were significantly associated with shorter survival. Conversely, longer survival times were observed among patients with a cervical interstitial infiltration depth ≤ 1/2 (HR: 0.09, 95% CI: 0.02–0.37, p = 0.001), a history of prior surgery (HR: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.06–0.31, p < 0.001), or an inadequate blood supply on ultrasonography (HR: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.08–0.48, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Variables that demonstrated statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis (age, prior surgery, cervical interstitial infiltration depth, ultrasonographic blood supply, and FIGO III–IV) were included in the multivariate Cox regression model. Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 3) further illustrated the prognostic impact of these variables.

Overall survival in the training cohort is shown by the Kaplan-Meier analysis. Surgery vs. no surgery (A), insufficient blood supply versus sufficient blood supply (B), lesion diameter < 40 mm versus ≥ 40 mm as determined by ultrasonography (C), cervical interstitial infiltration depth ≤ 1/2 versus > 1/2 (D), moderate/high differentiation versus poor differentiation (E), and FIGO stage III-IV versus I-II (F) are among the comparisons. Hazard ratio is equal to HR.

Developing a nomogram to predict the prognosis of cervical cancer patients

A prognostic nomogram was constructed based on the independent predictors identified in the multivariate analysis. The relationship between risk factors and overall survival in the training group was visualized using forest plots that display the HRs and CIs for both univariate and multivariate analyses (Fig. 4). Each predictor’s weighted contribution to overall survival was quantified to determine its relative influence on the total risk score.

Calibration and validation of the nomogram

The predictive accuracy and calibration of the nomogram were evaluated in both the training and validation cohorts. The model achieved strong discriminative performance, with C-index values of 0.841 (95% CI: 0.737–0.945) in the training cohort and 0.847 (95% CI: 0.743–0.951) in the validation cohort. The areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) for 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival were 0.844, 0.857, and 0.863, respectively, in the training set, and 0.838 for the validation set (Fig. 5). Calibration plots demonstrated close agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities at 1, 2, and 3 years, confirming the model’s reliability (Fig. 6).

Incremental predictive value and clinical utility

To assess the incremental prognostic value of the nomogram beyond the FIGO staging system, NRI and IDI were calculated at 36 months. In the validation cohort, the nomogram demonstrated significant enhancement over the FIGO model, with NRI = 0.700 (95% CI: 0.172–0.848, p < 0.05) and IDI = 0.239 (95% CI: 0.048–0.655, p < 0.05), indicating substantial improvement in risk discrimination and reclassification accuracy. DCA was conducted to evaluate the model’s net clinical benefit across threshold probabilities ranging from 1% to 60%. Compared with the FIGO staging model and the “Treat All” and “Treat None” strategies, the nomogram consistently demonstrated higher standardized net benefit in the training, validation, and overall datasets (Fig. 7). The largest gain in net benefit was observed between threshold probabilities of 10% and 25%, reflecting the nomogram’s superior clinical usefulness across realistic decision thresholds.

Risk stratification and survival analysis

Based on the linear predictor derived from the nomogram, patients were further classified into low-, medium-, and high-risk groups according to tertiles determined in the training cohort (cut-off values: −1.958 and − 0.030). These same cut-points were applied to the validation and overall datasets. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses showed clear separation among the three risk groups in the training and overall sets (p < 0.001) and a similar trend in the validation cohort (p = 0.12) (Fig. 8). The 36-month survival probabilities were 1.000, 0.937, and 0.784 in the training cohort; 0.969, 0.916, and 0.877 in the validation cohort; and 1.000, 0.968, and 0.850 in the overall population for the low-, medium-, and high-risk groups, respectively. These findings confirm that the nomogram effectively stratifies patients into distinct prognostic categories with meaningful differences in survival outcomes.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves by nomogram-derived risk tertiles in the training, validation, and overall cohorts. Distinct separation is observed between low-, medium-, and high-risk groups in the training (p < 0.001) and overall (p < 0.001) datasets, with a similar trend in the validation cohort (p = 0.12).

Discussion

Summary of the findings

In our study, five clinicopathological and ultrasonographic parameters were found to be independent prognostic variables of decreased overall survival in patients with cervical cancer. These included: (i) increased age – though showing a mild association with poor survival (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.06, p = 0.002), (ii) absence of prior surgery, (iii) greater cervical interstitial invasion, (iv) a rich tumoral blood supply identified on color Doppler, and (v) FIGO stage III–IV. Based on these variables, we developed a nomogram capable of estimating one-, two-, and three-year survival rates with excellent calibration and discrimination. The model achieved high concordance indices in both training and validation cohorts and maintained strong predictive accuracy across multiple performance metrics. Importantly, the model’s incremental value was confirmed by the significant net reclassification improvement (NRI = 0.700) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI = 0.239), indicating that the nomogram substantially improved risk prediction compared with the conventional FIGO staging system. Furthermore, decision-curve analysis demonstrated that the nomogram provided greater net clinical benefit than FIGO staging across a broad range of threshold probabilities. Finally, risk stratification by nomogram tertiles successfully separated patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk groups with significantly different survival outcomes.

Prior work

Nomograms have become increasingly prevalent in cancer prediction, with numerous studies developing nomograms for cervical cancer prognosis13,14,15. Prior nomograms often depend on clinicopathological factors, including FIGO stage, lymph node involvement, tumor size (typically assessed via MRI or CT), and histological classification2. For instance, Deng et al. developed a nomogram for stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer by combining variables such as age, tumor size, lymph node metastases, and serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels13. Nevertheless, only few studies have included ultrasonography findings, specifically tumor blood supply into prognostic models of cervical malignancies. Although the application of Doppler ultrasound in assessing cervical cancer staging and tumor vascularization has been evaluated by some investigations4,11, the findings have not yet been effectively translated into validated predictive nomograms. Moreover, our study addresses a gap in the current literature concerning the value of ultrasound in cervical cancer, as prior research has predominantly concentrated on diagnostic accuracy or relationships with other imaging modalities16.

Nomogram parameters

Increased age is a classic predictor of worse prognosis among patients with cervical cancer because of weaker immunity, more comorbidities, and fewer aggressive treatment options17. Likewise, advanced FIGO stages are linked to shorter survival due to increased tumor burden, higher rates of metastasis, and the requirement for more aggressive treatments, which may result in complications and a higher death rate18. The dichotomization of FIGO stages (I-II vs. III-IV) in our regression analysis was clinically justified as it reflects meaningful prognostic differences between earlier and advanced stage diseases. Lymph node metastases were excluded from our nomogram since it already corresponds to patients with FIGO stage III. It has been demonstrated that ultrasound can measure the size of cervical tumors with an accuracy level on par with MRI16. Tumor size is an important prognostic factor as larger tumors (> 4 cm) are frequently linked to greater recurrence rates19. However, our study did not find this correlation, perhaps because of the inclusion of many patients with tumors larger than 4 cm, which would have reduced statistical power. As determined by color Doppler Ultrasound, the tumor blood supply’s richness was a predictor of overall survival. Notably, The HR for insufficient blood supply was 0.19 in univariate analysis with more blood flow being associated with worse long-term results. Ultrasound can identify tumor angiogenesis, which could indicate tumor growth and metastasis potential thus contributing to a worse prognostic status20.

The rationale for implementing ultrasound

Ultrasound has various advantages in the clinical routine such as wide availability, mini-invasiveness and acceptable to good sensitivity and specificity in detecting pelvic lesions notably malignancies21. The cost-effectiveness of transvaginal sonography represents a key benefit particularly in resource-limited settings where access to MRI or PET-CT may be more restricted and the prevalence of cervical cancer may be higher10. Nonetheless, the place of this imaging modality in the diagnosis of cervical cancer is limited among physicians possibly causing a missed opportunity for earlier detection of cervical cancer. Although ultrasound was shown to be a useful technique for assessing local extent of disease in cervical cancer22 it is largely underused in this context which could be justified by important limitations such as the inability to distinguish between early malignant and benign lesions due to potential overlapping sonographic features23. A recent study found that despite being initially evaluated with ultrasound, the majority of patients with cervical cancer do not receive cervix examination causing significant abnormalities to be missed, potentially leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment24. These considerations motivated us to aim to add another purpose to ultrasound use in patients with cervical cancer demonstrating its predictive potential and reliability in patient stratification. This may further emphasize the value of ultrasound and increase focus on expanding its implementation in the evaluation and management of cervical cancer particularly in low-resource settings where advanced imaging techniques such as MRI are unavailable.

Utility of the nomogram in guiding therapeutic strategies

The developed nomogram can assist in identifying patients at elevated risk of early mortality and in tailoring adjuvant or intensified treatment strategies accordingly. For instance, women predicted to have lower survival probabilities may benefit from more aggressive chemotherapy or radiotherapy following surgery. Similarly, patients with highly vascularized or deeply infiltrating tumors on ultrasound may warrant closer surveillance schedules or multimodal therapy. Decision-curve analysis confirmed that applying the nomogram in clinical practice yields a consistent net benefit across a range of decision thresholds compared with FIGO stage-based management. The additional ability of the model to stratify patients into discrete risk groups facilitates individualized follow-up intensity and resource allocation, aligning with precision oncology principles. Together, these findings support the potential of the nomogram as a practical decision-support tool that complements existing staging systems and enhances personalized care.

Limitations and future directions

The single-center, retrospective data and limited follow-up duration represent key limitations to the present study. The model was first created and verified using data from a single Chinese institution, underscoring the necessity of external, multicenter, prospective validation studies. Thus, while the proposed predictive model was internally evaluated, it still needs to be validated externally by independent assessments. The follow-up period not exceeding five years, therefore more extensive studies are required to evaluate the performance of nomograms in predicting long-term survival outcomes. The study eliminated patients with insufficient data or severe disease, which could introduce a form of selection bias. Disease-specific survival could have been a more appropriate endpoint than overall survival as the latter can be affected by other cofounding factors not necessarily related to cervical cancer. The assessment of interstitial infiltration depth via ultrasound appears questionable and should ideally be confirmed through pathological examination. Finally, ultrasound evaluations are highly operator-dependent, which introduces subjectivity and exposes to possible inconsistencies where different clinicians may arrive at varying conclusions.

In summary, we developed and verified a nomogram that combines clinical characteristics and ultrasound data to predict cervical cancer survival, highlighting a potential application for clinical settings. Multicenter, prospective trials with prolonged follow-ups including new imaging modalities, biomarkers, and therapeutic status are warranted to optimize prognosis and decision-making. Finally, computerizing the nomogram could help integrate it into clinical practice.

Conclusion

The study efficiently merged clinicopathological variables with ultrasonographic data to build and validate a predictive nomogram for patients with cervical cancer. By integrating ultrasonography information including especially blood supply and interstitial infiltration of cervical malignancy, survival prediction model’s accuracy was remarkably boosted. While previous surgery and a lower tumor blood supply were linked to better survival outcomes, the results showed that advanced age and greater FIGO stage were associated with a worse prognosis. Accurate 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rate predictions are made possible by the nomogram’s strong calibration and discrimination, which are backed by a high concordance index and robust validation in both training and validation cohorts. This study emphasizes the clinical utility of ultrasonography as a readily available, reasonably priced, and non-invasive method of predicting patient outcomes, especially in environments with limited resources.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Arbyn, M. et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Global Health. 8(2), e191–e203 (2020).

Olusola, P. et al. Human papilloma Virus-Associated cervical cancer and health disparities. Cells. 8(6) (2019).

Shrestha, A. D. et al. Cervical cancer prevalence, incidence and mortality in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 19(2), 319–324 (2018).

Cohen, P. A. et al. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 393(10167), 169–182 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Trends of incidence rate and age at diagnosis for cervical cancer in China, from 2000 to 2014. Chin. J. Cancer Res. = Chung-kuo Yen Cheng Yen Chiu. 29(6), 477–486 (2017).

Bhatla, N. et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 145(1), 129–135 (2019).

Testa, A. C. et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of presence, size and extent of invasive cervical cancer. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 34(3), 335–344 (2009).

Ahmadzade, A., Gharibvand, M. M. & Azhine, S. Correlation of color doppler ultrasound and pathological grading in endometrial carcinoma. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 9(10), 5188–5192 (2020).

Epstein, E. et al. Sonographic characteristics of squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecology: Official J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 36(4), 512–516 (2010).

Salvo, G. et al. Measurement of tumor size in early cervical cancer: an ever-evolving paradigm. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer: Official J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 30(8), 1215–1223 (2020).

Epstein, E. et al. Early-stage cervical cancer: tumor delineation by magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound - a European multicenter trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 128(3), 449–453 (2013).

Deng, Y. R. et al. A preoperative nomogram predicting risk of lymph node metastasis for early-stage cervical cancer. BMC Women’s Health. 23(1), 568 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. A novel nomogram and risk stratification for early metastasis in cervical cancer after radical radiotherapy. Cancer Med. 12(24), 21798–21806 (2023).

Shan, Y. et al. Incidence, prognostic factors and a nomogram of cervical cancer with distant organ metastasis: a SEER-based study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 43(1), 2181690 (2023).

Théodore, C. et al. MRI and ultrasound fusion imaging for cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 37(9), 5079–5085 (2017).

Feng, Y. et al. Nomograms predicting the overall survival and cancer-specific survival of patients with stage IIIC1 cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 21(1), 450 (2021).

Matsuo, K. et al. Validation of the 2018 FIGO cervical cancer staging system. Gynecol. Oncol. 152(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.026 (2019).

Jurado, M. et al. Neoangiogenesis in early cervical cancer: correlation between color doppler findings and risk factors. A prospective observational study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 6(126) (2008).

Canaz, E. et al. Preoperatively assessable clinical and pathological risk factors for parametrial involvement in surgically treated FIGO stage IB-IIA cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer: Official J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 27(8), 1722–1728 (2017).

Menon, U. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol. 10(4), 327–340 (2009).

Alcázar, J. L., Arribas, S., Mínguez, J. A. & Jurado, M. The role of ultrasound in the assessment of uterine cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 64(5), 311–316 (2014).

Koutras, A. et al. Advantages and limitations of ultrasound as a screening test for ovarian cancer. Diagnostics 13(12), 2078 (2023).

Petrovick, T. et al. Pelvic ultrasound: A missed opportunity for earlier detection of cervical cancer? JCO. 43, e17538 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Bureau and Chongqing Municipal Health Commission Joint Project [The Funding Number:2024GDRC003].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualization: Xinru Deng. and Yanxu Lu; Methodology: Liuyun Cai, Xiaodong Luo, Yanxu Lu; Software: Liuyun Cai, Xiaodong Luo and Chenhuizi Wu; Validation: Liuyun Cai, Xiaodong Luo and Yanxu Lu; Formal analysis: Liuyun Cai and Xinru Deng; Investigation: Yanxu Lu; Resources: Xinru Deng; Data curation: Xiaodong Luo and Chenhuizi Wu; Writing—original draft preparation: Liuyun Cai, Xiaodong Luo and Chenhuizi Wu; Writing—review and editing: Xinru Deng. and Yanxu Lu; Visualization : Yanxu Lu; Supervision : Xinru Deng; Project administration : Xiaodong Luo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Ethical Code: 2025-082). All participants in the study provided their written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, L., Luo, X., Wu, C. et al. Prognostic value of ultrasonography findings in patients with cervical cancer. Sci Rep 15, 44471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28187-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28187-z