Abstract

Confining electrons or holes in quantum dots formed in the channel of industry-standard fully depleted silicon-on-insulator CMOS structures is a promising approach to scalable qubit architectures. In this article, we present our results on a calibrated model of a commercial nanostructure using the simulation tool QTCAD®, along with our experimental verification of all model predictions. We demonstrate here that quantum dots can be formed in the device channel by applying a combination of a common-mode voltage to the source and drain and a back gate voltage. Moreover, in this approach, the amount of quantum dots can be controlled and modified. Also, we report our results on an effective detuning of the energy levels in the quantum dots by varying the barrier gate voltages. Given the need and importance of scaling to larger numbers of qubits, we demonstrate here the feasibility of simulating and improving the design of quantum dot devices before their fabrication based on a commercial process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum dots formed through electrostatic means and material interfaces are the basis of one of the approaches to quantum computing hardware based on semiconductor materials1. Various degrees of freedom can be used to encode quantum information in these quantum dots, such as the charge or spin, in order to form a set of qubits. More exotic multi-particle spin states acting as qubits have also been demonstrated in semiconductor quantum dots, such as singlet/triplet, flip-flop, and hybrid states2. Fundamental to all of these implementations is the precise electrostatic control over the quantum dots and the barriers between them. A typical semiconductor structure hosting two quantum dots separated by barrier gates3 has the following components: two electron reservoirs for the injection of charge carriers from either end of the quantum dot array, three barrier gates to control tunnelling between adjacent quantum dots, and two plunger electrodes between the gates to control the electrochemical potential of the quantum dots.

In this paper, we focus on the modelling and experimental characterisation of a quantum dot array (QDA) in a commercial 22 nm Fully Depleted Silicon-On-Insulator (FDSOI) process from GlobalFoundries4. As opposed to conventional semiconductor quantum dot arrays2,5, our structure does not have any plunger electrodes between the gates. We demonstrate full electrical control over the location of the quantum dots, either underneath or between the gate electrodes, through a common-mode voltage applied to the source and drain terminals of the QDA and the barrier gate voltages. We also demonstrate an equivalency in the formation of quantum dots in the channel through the application of the common-mode voltage or the back-gate voltage. Confinement in other semiconductor QDAs is typically done below gate or plunger terminals6,7,8, however here we demonstrate confinement between barrier gate terminals without a dedicated plunger terminal. An effective plunger is then realised through variations in the common-mode voltage and the barrier gate voltages depending on the region of operation. Biasing through the common-mode voltage allows for moderate biasing voltages, given the top gates and source/drain regions in this device are not frozen out at 1 K (see Sect. "Simulation techniques and setup" for further discussion). The quantum well formation for a given biasing condition is accurately predicted in simulation and is confirmed with a range of experimental demonstrations. Thus, we also demonstrate the feasibility of simulating quantum transport properties of commercial semiconductor devices prior to fabrication. This is a key requirement for the design of future scalable quantum computing architectures using commercial semiconductor technologies9,10.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Sect. “System Overview” contains an overview of the device, including limitations of the commercial photo-lithography process. In Sect. "Simulation techniques and setup", we describe the semiconductor and quantum mechanical model used to predict the behaviour of the quantum dots in the device. Sects. "Flat band simulation and well location characterisation" and "Effective detuning of quantum dots in simulation" describe the simulation results using our model. Finally, Sect. “Measurement setup” and Sect. “Measurement results” are dedicated to the measurement setup and results that support the predicted operation of the device, such as charge stability diagrams, Coulomb blockade effects at 1 K, and bias triangle pair formation. We also demonstrate close matching between our experimental results and our device model.

System overview

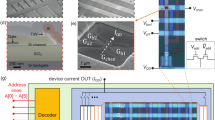

The device investigated in this study is fabricated using GlobalFoundries’ 22FDX® technology. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the device consists of a raised source and drain, and five electrostatic gates, and it serves as an initial test structure for future highly scalable QDAs based on industry-standard FD-SOI processes. We will explain the challenges encountered throughout the paper relating to the electrical control of the QDA structure.

3D view of the five-gate quantum dot array with raised source and drain. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a similar device shows dummy polysilicon gates that are not included in the 3D view. A backgate terminal is also available in this process but is not visible in this diagram. It connects through a metal VIA to the silicon wafer below the buried oxide.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, unlike other QDAs with quantum dots controlled by plunger gates2, this device admits indirect electrical control over quantum dots forming between the polysilicon barrier gates. The fabrication of the device does not require modification of the standard photolithography process11,12,13. We emphasise that the most pertinent feature of the standard processing that we must adhere to is standard sizing and pitch, which places strict constraints on the design of quantum dot devices in photolithography-fabricated devices. In our structure, the distance between neighbouring gates is approximately 1.5 to 2 times the size of the resulting quantum dots. The gates QA0 and QA1 act as spacers between the heavily doped source and drain and the quantum dots. Therefore, the electrical control scheme becomes more complicated compared to traditional structures with plungers as each gate affects both tunnel barriers and quantum dot energy levels. Later in the paper, we describe simulations and measurement results that demonstrate the biasing and detuning of the device without plunger gates.

When designing an experiment to control the formation of quantum wells in the channel of the device, it is necessary to keep the gate-to-source and drain-to-source voltage below 1.6 V, beyond which the sample would likely be damaged due to the breakthrough of the thin (\(\approx 10\) nm) silicon nitride spacer layer. Thus, the potentials applied to the terminals are applied with respect to the source (Table 1). All biasing conditions given with respect to the source are denoted without a prime (Table 1). Throughout the rest of the paper, we will prove that the number of quantum dots and effective detuning can be implemented in a commercial 22FDX® device using only a common-mode voltage and barrier gate voltages through simulation and experimental verification. We also demonstrate an equivalence between the common-mode voltage sweep and a back-gate voltage sweep, up to a minus sign, in our flat band measurement results.

Simulation techniques and setup

To examine if the number of quantum dots can be controlled through variations of the common-mode voltage and barrier gate voltages, we begin by building a model of our semiconductor nanodevice. However, the convergence of semiconductor equations below 70 K is highly numerically unstable due to the exponential dependence of ionised charge carriers on temperature14,15. Therefore, simulation results obtained below this temperature typically do not coincide with an experimental characterization of semiconductor transistors. For this reason, we used the highly specialized tool kit, QTCAD® by Nanoacademic Technologies16, allowing for semiconductor quantum dot modelling at deep cryogenic temperatures17,18. QTCAD® allows one to solve the Poisson and self-consistent Poisson-Schrodinger equations with the assumption that classical transport is forbidden in the fully depleted “dot region” where quantum dots are formed. In addition, one can compute single-electron wavefunctions in these dot regions, extract lever arms with respect to device terminals, and compute sequential tunnelling current. Such a model allows for the prediction of experimental biasing conditions for various operating modes of a QDA which we discuss throughout the rest of this paper.

In our current QTCAD® model, we use the following assumptions:

-

The gate polysilicon volumes are assumed to be conductive at cryogenic temperatures and are replaced by a set of equipotential boundaries with potentials and work functions. This approach significantly reduces the number of points to calculate without the introduction of a numerical error. This is a typical approach in TCAD modelling19.

-

Both nitride and foamed spacers are considered to be perfect insulators with dielectric constants of 9 and 2.7 respectively. In reality, both of these materials are non-crystalline and therefore have very complicated band structures. However, since we are focused on the silicon channel, we neglect this complication as we are not considering the effect of charges in the insulating regions. The exact material of the foamed spacer is not known, but is likely foamed \(\text {SiO}_{2}\) or foamed silicon nitride, based on what we have found through calibration of our model against experimental data.

-

The bottom of the buried oxide region is considered a frozen boundary, which is applicable when the thermal energy \(k_\text {B}T\) is much lower than the donor (acceptor) binding energy. This places the Fermi level in this region between the donor (acceptor) level and the conduction (valence) band edges20.

-

Source and drain metal contacts are considered ohmic boundaries. The source and drain boundary conditions are set by locally shifting the Fermi energy level by \(e V_\text {source}\) and \(e V_\text {drain}\) respectively, where e is the electron charge.

-

Mechanical stress in the silicon channel is neglected in this simulation. This can introduce a noticeable offset between the biasing voltages predicted by simulation and those used in the experiment19. This will be considered in future work.

The calibration of the QTCAD® model is central to its use in predicting biasing conditions. Without accurate calibration, we can learn very little from our model. The unknown parameters that we derive from the experiment are noted as follows: the doping concentration (\(n_\textrm{sd}\)) in the raised source and drain (in reality it is a function of space \(n_\textrm{sd}=n_\textrm{sd}(x,y,z)\) but is assumed constant over the drain/source volumes here), the gate work function \(E_\textrm{Wg}\), the back-gate work function \(E_\textrm{Wbg}\), and the doping concentration \(n_\textrm{bg}\) of the frozen back-gate region. Initial information for building our model was taken from publicly available process information, actual commercial processes may differ somewhat19. In our initial calibration, we used experimentally obtained \(i_\text {DS}(V_\text {CM})\) curves and qualitatively compared them with conduction band configurations from simulation. This allows us to reduce the possible range of many parameters in the semiconductor simulation. The gate polysilicon is assumed to be p-doped19. The simulation of a Gaussian doping distribution in the source and drain introduces an unreasonably high-density Finite Element Method (FEM) mesh. Therefore, uniform doping was assumed in all volumes of the source and drain domains. It is unclear what an equivalent doping concentration is in this approach, so we used a wide-range scan of the doping concentrations to match experimental results (See supplementary materials). We also used the standard frozen boundary condition on the back gate16.

A classification of the conduction bands (Fig. 2 allows further calibration of the QTCAD® model. A finer calibration was then done using an experimentally obtained Coulomb blockade in a minimum size 22FDX® transistor. We used biasing conditions that correspond to a single visible Coulomb diamond and the measured lever arm to fine-tune the simulator parameters (See supplementary materials for more details).

Flat band simulation and well location characterisation

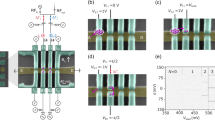

The first stage of the device characterization was a flat band simulation and experiment. This is a sweep of \(V_\text {CM}\) with all equal gate-to-source barrier voltages, \(V_\text {QT} = V_\text {QT0} = V_\text {QT1} = V_\text {QT2}\). The experimental results are reported in Sect. “Measurement results”. In the simulation, each biasing point was classified according to Fig. 2, with a unique colour for each device state. The conduction band edge has a complex 3D structure, with its cross-sections varying from the top of the channel close to the gate/channel interface down to the bottom of the channel, close to the buried oxide interface. Therefore, a quantitative classification into each of the states in Fig. 2.

Qualitative analysis of the flat band simulation. Each coloured pixel of the diagram corresponds to the broad shape of the conduction band in the device channel. Colours encode the conduction band configurations, which are shown on the right. In figures on the right, solid lines represent the conduction band configuration, dashed lines — Fermi levels, shaded areas — areas filled by electrons from reservoirs, and circles — insulated quantum dots. Blue encodes the situation when the device is completely resistive — there is a global barrier between reservoirs. Magenta encodes the situation when the quantum dot is formed under the central gate — the current is possible when the Fermi level is aligned with the quantum dot energy. Yellow encodes the quantum dots that are formed between gates — the current is possible when the Fermi level is aligned with both dots’ energy levels. Red encodes the conductive regime — when the conduction band is below the Fermi level everywhere. The back gate for the simulation is kept at \(0\,V\).

Figure 2 show the four distinct modes of operation of the device. A varying number of quantum dots form in the channel of the device in two of the states, which can be controlled by \(V_{\text {CM}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT}}\):

-

In the case of a quantum dot forming under QT1 (magenta curves in Fig. 2), the voltage applied to QT1 changes the energy levels of an electron trapped in this quantum dot. The ratio between the variation in the energy level in a quantum dot and the variation in the gate voltage is known as the lever arm. The potential barrier height separating the central quantum dot from the source and drain regions is controlled by the common-mode voltage and the two side barrier gate voltages, \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\).

-

In the case when quantum dots form between barrier gates (yellow curves in Fig. 2), the voltage applied to the barrier gate terminals controls the corresponding potential barriers between the quantum dots and the energies of the quantum dots to a lesser extent. The common-mode voltage primarily controls the energy of both quantum dots as an effective global plunger. However, for independent control of the energy levels in each of the two dots, we describe effective detuning later in this paper using the barrier gate voltages.

Given the operating modes noted above, the energy levels present in the quantum dots change with variations in both \(V_\textrm{QT}\) and \(V_\textrm{CM}\), which is verified experimentally. The choice of biasing conditions that prepare the device in one of the four states noted in Fig. 2 is dependent on the intended use. The creation of a single quantum dot under QT1 results in a quantum dot that is well isolated from the source and drain regions due to the large potential barriers. When the device is operated in the regime with quantum dots appearing between QT0/QT1 and QT1/QT2, we have two quantum dots with a controllable inter-dot potential barrier (QT1), and two more potential barriers separating the dots from the source and drain (QT0, QT2). In this latter case, the barriers are not as wide as in the case of the single quantum dot, and so the dot is more strongly coupled to the source and drain. Later in this paper, we utilize the fact that the barrier gate voltages affect the energy of nearby dots to control the energy levels in individual quantum dots.

Effective detuning of quantum dots in simulation

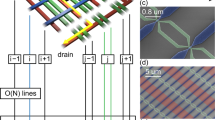

Given that we can bias our device as described in Fig. 2, we now describe the process of detuning our device in the double quantum dot state by sweeping the barrier gate voltages, \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\), whilst keeping all other voltages fixed. This allows us to demonstrate effective plungers that control the energy levels of the two quantum dots independently, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3(a) shows the variation in the conduction with variations in the voltage \(V_{\text {QT0}}\). The dips in the conduction band to the left and right of the central three-barrier structure are due to \(V_{\text {QA0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QA1}}\). The voltage \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) is swept from \(0.2~\text {V}\) to \(0.45~\text {V}\). Note the variation in the barrier height and the well depth. The change in the depth of the well is approximately linear, as shown in Fig. 3(c), where the change in single-electron orbital energies in the left quantum dot is linear. Therefore, we can define a leverarm to capture this linear response of the left-bound states with respect to variations in \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) of approximately \(0.261~\text {eV/V}\).

The same simulation is then also performed by sweeping \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) over the same range. The conduction band response and state energy variation are shown in Fig. 3(b),(d). Note again that the states bound in the left quantum dot are essentially unaffected by variations in \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) while states bound in the right quantum dot respond with a leverarm relation of approximately \(0.261~\text {eV/V}\). Therefore, simulation suggests that the barrier gate voltages \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) can act as plungers, directly controlling the energy of the bound states in the left and right quantum dots, respectively.

Effective detuning of quantum dots forming between QT0/QT1 and QT1/QT2 by sweeping the voltages \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) respectively. (a),(b) show the conduction band and its response to sweeps in \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) respectively. The horizontal line shown in both conduction band plots at \(0~\text {eV}\) is the Fermi level. (c),(d) define leverarms capturing the linear response of states bound in the left and right quantum dots to sweeps in \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) respectively. Notice that \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) has very little effect on states bound in the quantum dot that is not directly adjacent to it. The same is also true for \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) and the left quantum dot. (e) shows the first 10 single-electron orbital states and their location in the double quantum dot system.

We can also estimate the size of the wavefunctions and see how they compare to the pitch of the barrier gates in this device. For a quantum dot forming between two barrier gates separated by a pitch of 90 nm, the ground state wavefunction has the following extent in the X, Y, and Z directions (allowing for 3 standard deviations around its central point): [15 nm 47 nm 3 nm]. Even though the ground state wavefunction size is not comparable to the pitch, we do show clear single and double dot control in Sect. “Measurement results” through higher energy states, which would typically be larger in size and more comparable to the pitch.

We also note that there is excellent agreement between the predicted leverarm in QTCAD® simulation (\(\approx 0.261~\text {eV/V}\)) for control of dots between gates and that measured in experiment (\(\approx 0.2701~\text {eV/V}\)). See Sect. “Measurement results” for Coulomb diamond measurement results and the method used to extract the leverarm.

Measurement setup

The test chip is placed in a cryo-cooler which is capable of reaching 40 K, 4 K, and 1 K in three stages. The Quantum Machines OPX+21 is used for supplying a radio-frequency (RF) reflectometry input signal from the RF carrier channel and for digitizing the reflected signal on the digitizer channel. A QDevil QDAC-II is triggered by the OPX+, and the DC voltages are loaded to the QDAC-II in advance and swept by trigger signals from the OPX+. This allows for synchronization between DC voltage sweeps and RF-reflectometry readout. Further details of the experimental setup are shown in the supplementary material. Reflectometry is performed on the source of the device which is tunnel coupled to the quantum dots forming in the channel. In this setup, the source acts as a lead for dispersive charge sensing. This is tunnel coupled to the quantum dots in the channel which act as a two-well single electron box (SEB) given that the drain lead is effectively disconnected. In this way, RF-reflectometry can then be used to detect inter-dot transitions22.

A flat band experiment, as demonstrated in simulation in Sect. "Flat band simulation and well location characterisation", is also measured experimentally. We then investigate the various biasing regions as noted in Fig. 2. To differentiate between single and double quantum dot confinement in the channel of our device, we first bias our device in a double quantum dot configuration. Then, by increasing \(V_{\text {QT1}}\), the double quantum dot becomes a single quantum dot, and this is evidenced by the change in the measured charge stability diagram23. We also measure bias triangle pairs to further confirm the presence of double quantum dots in the channel of a device similar to that described in Fig. 1.

Measurement results

Flat band

The flat band measurement results (Fig. 4) show a partitioning that is qualitatively similar to that predicted in simulations, with a characteristic slope separating the conducting and non-conducting regions. We provide flat band measurements using both a sweep in \(V_{\text {CM}}\) and \(V_{\text {BG}}\) to show their equivalency, up to a negative sign. A number of Coulomb blockade transitions can be seen moving between the conducting and the non-conducting regions, shown as separated transition lines at approximately \(V_{\text {QT}} = 0.4~\text {V}\) (Further highlighted in the Supplementary Material). Similar flat band experiments, demonstrating Coulomb Blockade transitions, have been demonstrated in the literature24.

Flat band measurement results showing both magnitude and phase response. The characteristic slope between the conducting and non-conducting regions is clearly visible in the RF magnitude (a) and RF phase measurements (b) for a \(V_{\text {CM}}\) sweep. To emphasise the equivalency between the \(V_{\text {CM}}\) and \(V_{\text {BG}}\) control, we repeated the same flatbands but for a sweep over \(V_{\text {BG}}\) for both RF magnitude and RF phase in (c) and (d) respectively. Note essentially the same flatband response for \(-V_{\text {BG}}\) for both the magnitude (c) and phase (d) as saw for the \(V_{\text {CM}}\) sweep. Overlaid on (a) are points of the same colour showing the slope between the non-conducting and conducting regions. This is then overlaid on the theoretical plot in (e), showing excellent matching with the slope of the conducting region from our calibrated model.

We note that the measured flat band does not show the confinement regions quite so neatly as in simulation. Given the noise and uncertainty present in experiment, the boundary becomes blurred compared with simulation. We also note that the measured RF signal provides only an insight into the underlying conduction processes which may not appear to change for dots under versus dots between gates in the flat band. This is particularly clear when we extract the slope of the transition between non-conducting and conducting regions from the experimental result in Fig. 4(a) and overlay it on the theoretical flatband in Fig. 4(e). Note the excellent matching of the experimental slope with the conducting region in red. However, note the gap between the 1-well region and the measured slope. This further highlights that while in experiment there is measurable conduction in this gap, it is not evident from our electrostatic analysis in the theoretical flatband. We also note that the 2-well region in Fig. 4 is not visible as a region of conduction in the experimental results, likely presenting too high an impedance for measurable conduction in experiment. The ultimate test is to appeal to charge stability plots and leverarm analysis at a point in the flat band to understand the nature of confinement at that point. We highlight a bias point in Fig. 4 which is used in Sect. "Quantum dot location" to verify theoretical leverarm predictions in experiment and to verify the confinement location and the excellent matching between theory and experiment. Double quantum dots are then demonstrated in a similar device in Sect. "Charge stability diagrams".

Even though this is a commercial process, disorder effects due to imperfections and charge trapping in the silicon and surrounding insulating materials are still to be expected, resulting in some of the noisy transitions seen in Fig. 4. There is also some evidence of charge noise in the later measurements, see Fig. 7. We suspect this is due to charge trapping and surface roughness at the silicon dioxide interface that the wavefunction is confined against. It is well documented in literature that this is the case in silicon processes25,26. One advantage of 22FDX® is the backgate voltage, which can be used to tune the location of the quantum dot away from these interfaces. This will be explored in future work.

Quantum dot location

We then verify the prediction of leverarms for dots between and under gates from our simulations versus those measured in experiment. From Fig. 3, we see that the leverarm, \(e\alpha\), predicted by simulation for controlling quantum dots forming between gates is approximately \(0.261\pm 0.005\,\text {eV}/\text {V}\). Likewise, the predicted leverarm for quantum dots forming under gates can also be inferred from Fig. 3 by tracking the change in the barrier height over the \(V_{\text {QT}}\) sweep. In this case the predicted under gate leverarm is approximately \(0.874\,\text {eV}/\text {V}\). Given these predictions, we can then easily check the location of the quantum dot in measurement.

Therefore, we first made a measurement of Coulomb diamonds with respect to \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) in the vicinity of \(0.4\,\text {V}\) with \(V_{\text {BG}} = 2\,\text {V}\). From the flat band in Fig. 2 we would approximately expect quantum dots to form between gates. The measurement results are presented below in Fig. 5 along with a calculation of the leverarm extracted using the slopes of two intersecting lines27. The hand calculation, \(0.2703 \text {eV}/\text {V}\), then shows very close matching with the leverarm predicted by QTCAD® simulation for quantum dots forming between gates. This very close matching between experiment and simulation validates the calibration done for our device model. See Section. 1 in the Supplementary Material for a quantum dot forming under a gate, where again we see close agreement between our simulated leverarm and our Coulomb diamond measured leverarm.

The details of the hand calculation to extract the leverarm, which is then scaled by the electron charge e.

An approximate \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) distance of \(5.4045~\text {mV}\) is measured for the blocked current region to the right of the slopes annotated in Fig. 5, denoted \(\Delta {V}_{\text {add}}\). This gives a rough indication of the addition energy, \(E_{\text {add}}\), of the quantum dot at this filling using the following formula28:

This is in reasonable agreement with another device with smaller quantum dots in the literature, which results in somewhat higher addition energies (\(\approx 5~\text {meV}\))29. Given we can create quantum dots between the gates and we provide experimental evidence of such, we then move to demonstrating the formation of a controllable double quantum dot for a similar device.

Charge stability diagrams

To verify the presence of single(double) quantum dot(s) forming in the channel of the 22FDX® structure, charge-stability diagrams were then measured with RF-reflectometry on the source, and are shown in Fig. 6 for a device similar to that in Fig. 1, albeit with a shifted flat band response compared with that in Fig. 2. In this case we apply \(V_{\text {CM}} = -0.8\,\text {V}\). Charge stability diagrams show transitions between charge stable regions or equilibrium electron numbers, which varies strongly depending on the number of available quantum dots23.

Measured charge stability diagrams showing the formation of a double quantum dot and a single quantum dot depending on the applied voltage of the central barrier gate \(V_{\text {QT1}}\). Control over the quantum dot(s) is demonstrated by sweeping \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\). Here \(V_{\text {CM}} = -0.8\,\text {V}\), which is equivalent to \(V_{\text {BG}} = 0.8\,V\). Recall the flat band response of the device for these measurement results is qualitatively similar but shifted to those in Fig. 2.

Both the magnitude and phase response of the RF reflectometry signal are shown for three values of \(V_{\text {QT1}}\). As the value of \(V_{\text {QT1}}\) is changed from \(0.33~\text {V}\) to \(0.35~\text {V}\) a clear change in the charge stability response is noted. For the lowest value, \(V_{\text {QT1}} = 0.33~\text {V}\), there is a clear indication of double-quantum-dot charge transitions for \(V_{\text {QT2}}> 0.42~\text {V}\) in both the magnitude (Fig. 6(a)) and phase (Fig. 6(b)) response. Given that RF reflectometry takes place on the source reservoir, which is more strongly coupled to variations due to \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) than to \(V_{\text {QT2}}\), we see a strong phase response connecting charge transition points in the \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) direction30. There is very low coupling between variations in \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) given the double dot stability diagram is approximately square, with charge transition lines almost horizontal and vertical.

We note that as \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) increases, the coupling between the drain reservoir and the double quantum dot system increases. Therefore, as the drain to double-quantum-dot tunnel coupling increases, we expect the impedance of the system to become more sensitive to transitions between the drain reservoir and double quantum dot. This is clearly seen in Fig. 6(a),(b),(c),(d), where the lines connecting charge transition points appear completely suppressed for \(V_{\text {QT2}} < 0.42~\text {V}\). For \(V_{\text {QT2}}> 0.42~\text {V}\) faint lines begin to appear connecting charge transition points, quickly becoming wider as \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) increases. This is more obvious for \(V_{\text {QT1}} = 0.34~\text {V}\) than for \(V_{\text {QT1}} = 0.33~\text {V}\) as the double quantum dot states are more strongly hybridised in the former. Therefore the overall impedance of the system, as sensed through reflectometry, shows an increased dependence on the drain reservoir coupling for \(V_{\text {QT1}} = 0.34~\text {V}\).

As we increase \(V_{\text {QT1}}\) to \(0.34~\text {V}\) we further confirm its action as a barrier separating two quantum dots. By decreasing the potential barrier between the two quantum dots we observe a stronger coupling in the double quantum dot stability response in both the magnitude (Fig. 6(c)) and phase (Fig. 6(d)) response. Note the increased response connecting the charge transition points in both \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) for \(V_{\text {QT2}}> 0.42~\text {V}\), especially in the phase response (Fig. 6(d)). Further increasing \(V_{\text {QT1}} = 0.35~\text {V}\) shows a dramatic change in the charge stability response. We have very clearly moved from a double quantum dot charge stability response to a single quantum dot response, equally coupled to both \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) given the \(45^{\circ }\) slope of the transition lines in Fig. 6(e),(f).

Bias triangle pair formation

To further verify the presence of double quantum dots in the channel of the QDA, we investigated the formation of bias triangle pairs in a device similar to that described in Fig. 1 at 1 K. These are a clear hallmark of double quantum dot transport23. The bias triangle pairs form at the charge transition points, such as those shown in Fig. 6 with the application of \(V_{\text {DS}}\). The measurement results are shown in Fig. 7, with a zoomed in version of the triangles in location 5 shown in Fig. 8. The measurements, in this case, were taken using video-mode31 using superconducting inductors, as longer measurements were subject to charge noise and were difficult to analyse. In this case, there is a noticeable filtering effect on the measurement data due to the nature of video-mode, causing a compression of the data for low \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) in Fig. 7.

The bias triangle pairs appear for both a small negative and positive \(V_{\text {DS}}\), showing a reversal in their direction as is expected23. The formation of well-defined double quantum dots in this device, similar to that in Fig. 1, further demonstrates the repeatable nature of these results.

Charge stability sweep on voltages \(V_{\text {QT0}}\) and \(V_{\text {QT2}}\) with a small negative and positive \(V_{\text {DS}}\), with \(V_{\text {BG}} = 1.55\,\text {V}\). The location of the triangle pairs shifts somewhat over time so we label them \(1-9\). In the negative (a) and positive (b) cases, \(V_{\text {DS}} \approx -0.3~\text {mV}\) and \(V_{\text {DS}} \approx 0.7~\text {mV}\) respectively, with the asymmetry due to an offset in the measurement setup. Improved matching and a superconducting inductor allowed for a wider range of magnitude response to be captured in this set of measurements.

A zoomed-in version of Fig. 8 for just triangle pair 5 is shown in Fig. 8. An indication of the idealised bias triangle pairs is also shown, with an approximate fitting achieved by aligning with the back edge of the measured data. The base of the triangles corresponds to an alignment of the energy levels in the two quantum dots. The sides of the triangles then correspond to the level in one of the quantum dots, aligning with the Fermi level in its adjacent reservoir23.

Zoom on bias triangles 5 from Fig. 7 for both negative (a) and positive (b) \(V_{\text {DS}}\). An indication of the ideal bias triangles are overlaid on the figures.

For further experimental bias triangle results on a newer generation of device, see our results in32.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated experimentally (supported through modelling and theory) the electrostatic control and existence of single and double quantum dot formation in the channel of a fully commercial 22FDX® device at 1 K. Biasing in any desired device state, as outlined in Fig. 2, is achieved through a combination of common-mode voltage, back-gate voltage, and barrier gate voltages. An equivalency between common-mode and back-gate control was also demonstrated. Detuning of energy levels in the double quantum dot state is achieved through variations in the barrier gate voltages without a need for inter-barrier-gate plunger electrodes. There is a clear experimental demonstration of both single and double quantum dot charge transitions as predicted by our simulations. We demonstrate well-controlled single and double quantum dots with only barrier gate variations. Accurate prediction and characterisation of quantum well formation in these commercial devices enables us to more precisely determine the quantum dot biasing conditions. This also allows for the potential future demonstration of qubit formation and charge sensing using a commercial device at 1 K.

Data availability

Data supporting this study are openly available from https://github.com/equal1/Common_mode_control_publication_public_data/tree/main. An additional data can be sent by a reasonable request.

References

Chatterjee, A. et al. Semiconductor Qubits In Practice. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-021-00283-9 (2021).

Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M. & Petta, J. R. Semiconductor spin qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 025003. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.95.025003 (2023).

Vahapoglu, E. et al. Coherent control of electron spin qubits in silicon using a global field. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 126, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00645-w (2022).

Ong, S. et al. 22nm FD-SOI Technology with Back-biasing Capability Offers Excellent Performance for Enabling Efficient, Ultra-low Power Analog and RF/Millimeter-Wave Designs. 323–326, https://doi.org/10.1109/RFIC.2019.8701768 (2019).

Seidler, I. et al. Conveyor-mode single-electron shuttling in Si/SiGe for a scalable quantum computing architecture. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00615-2 (2022).

West, A. et al. Gate-based single-shot readout of spins in silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 437–441. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0400-7 (2019).

Ciriano-Tejel, V. N. et al. Spin readout of a CMOS quantum dot by gate reflectometry and spin-dependent tunnelling. PRX Quantum 2, 010353. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.010353 (2021).

Piot, N. et al. A single hole spin with enhanced coherence in natural silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1072–1077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-022-01196-z (2022).

Costa, D., Simoni, M., Piccinini, G. & Graziano, M. Advances in Modeling of Noisy Quantum Computers: Spin Qubits in Semiconductor Quantum Dots. IEEE Access 11, 98875–98913. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3312559 (2023).

Vinet, M. The path to scalable quantum computing with silicon spin qubits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1294–1296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-021-01037-5 (2021).

Wu, Q., Li, Y. & Zhao, Y. The Evolution of Photolithography Technology, Process Standards, and Future Outlook. In 2020 IEEE 15th International Conference on Solid-State & Integrated Circuit Technology (ICSICT), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSICT49897.2020.9278164 (2020).

Hou, Y. & Wu, Q. Optical Proximity Correction, Methodology and Limitations. In 2021 China Semiconductor Technology International Conference (CSTIC), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/CSTIC52283.2021.9461507 (2021).

Park, S. Y., Lee, S., Yang, J. & Kang, M. S. Patterning Quantum Dots via Photolithography: A Review. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300546. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202300546 (2023).

Beckers, A., Jazaeri, F. & Enz, C. Cryogenic MOS Transistor Model. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 65, 3617–3625. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2018.2854701 (2018).

Gao, X. et al. Quantum computer aided design simulation and optimization of semiconductor quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 164302. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4825209 (2013).

QTCAD®: A Computer-Aided Design Tool for Quantum-Technology Hardware, Nanoacademic Technologies Inc. (2022).

Beaudoin, F. et al. Robust technology computer-aided design of gated quantum dots at cryogenic temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 264001. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0097202 (2022).

Kriekouki, I. et al. Interpretation of 28 nm FD-SOI quantum dot transport data taken at 1.4 K using 3D quantum TCAD simulations. Solid-State Electron. 194, 108355, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2022.108355 (2022).

Maiti, C. Introducing Technology Computer-aided Design (TCAD): Fundamentals, Simulations and Applications (Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Limited, 2017).

Pierret, R. Advanced Semiconductor Fundamentals. Modular series on solid state devices (Prentice Hall, 2003).

Quantum Machines, www.quantum-machines.co

Vigneau, F. et al. Probing quantum devices with radio-frequency reflectometry. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 021305. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0088229 (2023).

Van Der Wiel, W. G. et al. Electron transport through double quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.75.1 (2002).

Yamada, K., Kodera, T., Kambara, T. & Oda, S. Fabrication and characterization of p-channel Si double quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 113110. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4896142 (2014).

Vinet, M. et al. Material and integration challenges for large scale Si quantum computing. In 2021 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 14.2.1–14.2.4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM19574.2021.9720708 (2021). ISSN: 2156-017X.

Martinez, B. & Niquet, Y.-M. Variability of Electron and Hole Spin Qubits Due to Interface Roughness and Charge Traps. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 024022. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.17.024022 (2022).

Venkatachalam, V., Hart, S., Pfeiffer, L., West, K. & Yacoby, A. Local Thermometry of Neutral Modes on the Quantum Hall Edge, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1202.6681 (2012). ArXiv:1202.6681.

Kouwenhoven, L. P., Austing, D. G. & Tarucha, S. Few-electron quantum dots. Reports on Prog. Phys. 64, 701–736. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/64/6/201 (2001).

Lim, W. H., Huebl, H., Angus, S. J., Clark, R. G. & Dzurak, A. S. Electrostatically de?ned few-electron double quantum dot in silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 3 (2009).

Chorley, S. J. et al. Measuring the complex admittance of a carbon nanotube double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 036802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.036802 (2012).

Stehlik, J. et al. Fast Charge Sensing of a Cavity-Coupled Double Quantum Dot Using a Josephson Parametric Amplifier. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 014018. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.4.014018 (2015).

Power, C. et al. Fully-Tunable Tunnel-Coupled Quantum Dots and Charge Sensing in a Commercial 22nm FD-SOI Process. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1–1, https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2025.3595384 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was done under the Disruptive Technologies Innovation Fund QCoIr EI Project, Ireland, 166669/RR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Sokolov: Simulations (lead); Data processing (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (lead); Experiments (supporting); Writing — original draft (equal); Writing — review & editing (supporting). X. Wu: Data processing (equal); Investigation (equal); Software (equal); Validation (equal); Experiments (lead); Writing — original draft (equal); Writing — review & editing (equal). C. Power: Data processing (equal); Investigation (equal); Software (supporting); Validation (equal); Visualization(supporting); Writing — original draft (lead); Writing — review & editing (equal). M. Asker: Data processing (equal); Methodology (equal); Experiments (equal); Software (equal); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (equal). P. Giounanlis: Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Data processing (supporting); Validation (equal); Experiments (equal); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (equal). I. Kriekouki: Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Data processing (supporting); Validation (equal); Visualization (supporting); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (equal). P. Hanos-Puskai: Software (lead); Visualization (supporting); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (equal). C. McGeough: Data processing (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Experiments (equal); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (supporting). I. Bashir: Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Data processing (supporting); Validation (equal); Experiments (equal); Writing — original draft (supporting); Writing — review & editing (equal). D. Redmond: Data processing (equal); Experimental methodology (equal); Experiments (supporting); Conceptualization (supporting); Validation (equal); Writing — review & editing (supporting). D. Leipold: Conceptualization (lead); Funding acquisition (lead); Project administration (equal). R. B. Staszewski: Conceptualization (supporting); Funding acquisition (equal); Resources (equal). E. Blokhina: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (lead); Methodology (lead); Supervision (lead); Validation (supporting); Writing — original draft (equal); Writing — review & editing (equal). All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sokolov, A., Wu, X., Power, C. et al. Common-mode control and confinement inversion of electrostatically defined quantum dots in a commercial CMOS process. Sci Rep 15, 45156 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28278-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28278-x