Abstract

Expanding HIV testing coverage is essential to achieving the first target of the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals. Under current circumstances, a novel testing method, urine-based HIV self-testing (HIVST) will be essential to reach undiagnosed people living with HIV. This multicenter cross-sectional study conducted in three sites in China evaluated the diagnostic accuracy, usability, and acceptability of urine-based HIVST in untrained users under real-world conditions. Among 1,495 participants, the urine test demonstrated a sensitivity of 99.44% and a specificity of 100.00%, with perfect agreement between self-testers and professionals. Agreement between home-based and facility-based testing was 100.00%, confirming the reliability of self-testing in unsupervised settings. Most participants were able to perform the test correctly and interpret the results independently, achieving high comprehension and satisfaction levels. Urine-based HIVST is accurate, convenient, and highly acceptable, serving as a promising alternative to blood- or oral fluid-based approaches to better accommodate diverse needs and preferences. This non-invasive and user-friendly testing option is expected to expand testing coverage and contribute to achieving the first UNAIDS 95 target in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has set the global “95-95-95” targets to end the HIV epidemic by 2030: 95% of all people living with HIV should know their status, 95% of those diagnosed should receive sustained treatment, and 95% of those on treatment should achieve viral suppression1. According to data reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) at the end of 2022, 86% of people living with HIV were aware of their infection status; however, an estimated 5.46 million individuals remained undiagnosed2. The first 95% target has not been achieved. In China, the progress towards this target was 79%, 93% and 96% by the end of 20203. HIV testing is an important first step to achieve the goal of UNAIDS 95-95-95. Therefore, it is necessary to expand testing in order to detect more undetected infected individuals.

With the development of testing technology and the popularization of HIV-related knowledge, HIV self-testing (HIVST) has been recognized by the WHO as a safe, acceptable, and accessible testing strategy, which plays a crucial role in bridging the major gap in HIV testing coverage4,5. HIVST is a process of collecting samples, performing the test, and interpreting results—either alone or with someone they trust—typically at home or in community settings. Both supervised and unsupervised HIVST approaches have been found to be highly acceptable, preferred, and more likely to encourage partner testing6,7,8,9. In addition to increasing testing frequency and improving access among key populations and their partners, HIVST can also identify newly diagnosed HIV infections at a relatively low cost10,11,12,13. Accurate and regulated HIV self-tests currently available include blood-based and oral-based kits, providing multiple options for self-testing14. While oral fluid-based HIVST tests are generally more acceptable because they do not require finger pricking and are perceived as safer, blood-based HIVST demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity, as antibody levels in oral fluid are lower than those in blood15,16,17,18.

In August 2019, the HIV SELF TEST BY URINE – Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) type-I urine antibody diagnostic kit (colloidal gold) (Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) was approved by the China National Medical Products Adimistration19. In April 2025, it received prequalification from the WHO, becoming the first commercially available urine-based HIV diagnostic test that can be self-administered and interpreted by lay users20. This test can provide results within 15 min, and all testing procedures can be completed on-site. Compared with blood-based HIVST, urine-based HIVST requires fewer steps and avoids finger pricking or precision pipetting. Unlike oral fluid-based HIVST, urine collection is more straightforward, reducing the risk of sampling errors. Despite growing evidence supporting urine-based HIVST, data from large-scale real-world evaluations in China remain insufficient21.

In our procedure, laboratory professionals obtained urine and blood samples from participants and conducted corresponding HIV tests. Participants were arranged to complete a questionnaire about instructions for use (IFU), interpreted results and conducted urine-based HIVST at home and in clinical settings. This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of urine-based HIVST compared with the laboratory reference standard (Western blot). It also assessed the usability of the test, referring to untrained users’ ability to perform and interpret it correctly without professional help, and to explore the acceptability of urine-based HIVST among participants.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2017 to June 2018 across Beijing, Yunnan, and Henan. Participants were divided into three groups: the HIV-infected group, the interference group, and the general population group. The grouping criteria were as follows: (1) HIV-infected group: Individuals confirmed to be HIV-positive by Western blot (WB) using the HIV Blot 2.2 kit (MP Diagnostics, Singapore); (2) Interference group: Individuals who tested negative for HIV but were clinically diagnosed with other viral infectious diseases, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis A virus, hepatitis E virus, syphilis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster, genital herpes, or co-infection with HBV and HCV; (3) General population group: Individuals without any of the above conditions. Exclusion criteria included age under 18 years, lack of informed consent, or incomplete identification information.

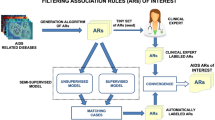

Study procedure

The study consisted of two main components: laboratory evaluation and usability evaluation. The laboratory evaluation employed a controlled trial design to primarily assess the clinical performance of the urine-based HIVST. The usability evaluation involved a questionnaire, result interpretation, and self-testing both at home and in clinical settings. Figure 1 contains a flow diagram of the study design and the progression of participants throughout the study.

To assess the participants’ proficiency in performing urine-based HIVST, they were required to complete a questionnaire independently, without any guidance, after reading and understanding the IFU (Supplementary Note 1 and Note 2) and label information, but before conducting the urine self-test. The IFU was written in plain, easy-to-understand Chinese and included step-by-step pictorial instructions to facilitate independent use by lay users. To further assess participants’ ability to interpret results, they were asked to evaluate pre-made contrived test devices showing strong positive, weak positive, negative, and different invalid results (Supplementary Figure S1).

Each participant independently collected two urine samples. One sample was used by the participant to perform the HIVST using the HIV-1 Urine Antibody Diagnostic Kit (colloidal gold; Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and the results were interpreted independently according to the IFU. Participants read the IFU on their own—either before or during the self-testing process—without any explanation from study staff or time limitations. Laboratory professionals observed the entire procedure without intervention and recorded any operational errors or difficulties encountered. The second urine sample was tested by laboratory professionals using the same diagnostic kit. If the test was not performed immediately, a urine preservation solution was added, and the sample was stored under refrigeration at 2–8 °C. Before testing, the stored sample was brought to room temperature, thoroughly mixed, and then analyzed using the same procedure. Simultaneously, blood samples were collected, and laboratory professionals performed a standard rapid blood test using the HIV Antibody Diagnostic Kit (third-generation ELISA; Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). ELISA-positive samples were confirmed by WB (MP Diagnostics, Singapore) in accordance with the National Guideline for Detection of HIV/AIDS22. For samples with indeterminate WB, the participant was followed up for repeat WB testing every 2–4 weeks until the WB testing had a definitive positive or negative result. When the urine and blood test results were inconsistent, laboratory professionals re-tested the retained urine samples using the third-party HIV-1 Urine Antibody Detection Kit (third-generation ELISA; Junhe Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). All experimental procedures were strictly conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Furthermore, to evaluate the influence of environmental factors and supervisory pressure, participants were given the option to repeat the HIVST at home and return their results to the laboratory. The consistency between self-test results obtained in clinical settings and those conducted at home was then analyzed.

Samples were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) incomplete or unclear identification information; (2) frozen and thawed more than three times; or (3) insufficient sample volume for testing. The urine-based HIVST results were not used for clinical diagnosis or treatment initiation during the study period and were utilized exclusively for research and evaluation purposes. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated to evaluate the validity of urine-based HIVST. The agreement rate and Cohen’s kappa coefficient were used to assess the reliability of the test. Additionally, positive and negative predictive values (PPV/NPV) were calculated to evaluate the overall diagnostic performance. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All confidence intervals (CIs) presented were 95% CIs.

The questionnaire comprised 12 questions, with each of the first 10 questions worth 10 points. The remaining two questions were non-scored, but responses from all participants were recorded. Only completed questionnaires were included in the evaluation. Scores were classified into two categories: low (≤ 80) and high (90–100). Participants within the low score range were considered to have insufficient understanding of the IFU, whereas those with high scores were considered to demonstrate excellent comprehension. Participants in the questionnaire survey were divided into three groups: HIV-infected individuals, high-risk individuals (e.g., MSM with multiple sexual partners/unprotected sex, injection drug use, irregular blood donation/transfusion, and those with high-risk behaviors such as having sex with HIV-infected individuals), and low-risk individuals (those who did not exhibit these behaviors). Differences between groups within variables were analyzed using Chi-square tests. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical approval statement

The study was approved by Beijing Youan Hospital (Approval No. [2017]069), the Sixth People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou (Approval No. IEC-2017-015), and the Yunnan Center for Disease Control and Prevention Ethics Committee.

Results

Participant demographics and group classification

A total of 1,614 individuals from Beijing, Henan, and Yunnan were initially recruited between December 2017 and June 2018. Of these, 1,495 participants were enrolled, while 119 were excluded (Fig. 1). Thus, the final valid sample comprised 1,495 participants, of whom 303 (20.27%) were female, and 1,192 (79.73%) were male. The mean age of the participants was 37.44 ± 13.86 years. Among the participants, 451 (30.17%) were HIV-infected individuals, 133 (8.9%) were part of the interference group, and 911 (60.93%) were from the general population. Within the HIV-infected group, 359 (24.00%) had not received antiretroviral therapy (ART), while 92 (6.00%) were undergoing ART (see Supplementary Table S1).

Diagnostic performance

In laboratory testing, the positive detection rates in infected individuals without ART were 99.44% (357/359) for urine samples and 99.72% (358/359) for blood samples. In contrast, among those receiving ART, the positive detection rates were 78.26% (72/92) for urine samples and 98.91% (91/92) for blood samples, respectively. Given the impact of ART on HIV test results and current recommendations discouraging the use of urine-based HIVST kits among HIV-infected individuals receiving ART, such individuals were excluded. HIV testing was therefore evaluated using urine and blood samples from participants not receiving ART.

Laboratory professionals tested blood and urine samples from 1,403 participants. Using the urine HIV self-test kit, 357 samples tested positive and 1,046 tested negative, while using the blood-based HIV Antibody Diagnostic Kit, 360 samples tested positive and 1,043 tested negative (Table 1). Western blot served as the reference standard for evaluating the diagnostic performance of both urine- and blood-based HIV test kits. For the urine test kit, the sensitivity was 99.44% (95% CI: 97.78–99.90%); the specificity was 100.00% (95% CI: 99.54–100%) and Youden’s index was 0.994 (95% CI: 0.973–0.999). The PPV was 100.00% (95% CI: 98.67–100.00%) and the NPV was 99.81% (95% CI: 99.23–99.97%). The sensitivity of the blood test kit was slightly higher than that of the urine test kit (sensitivity: 99.72%; 95% CI: 98.21–99.99%), while its specificity was lower than that of the urine test kit (specificity: 99.81%; 95% CI: 99.23–99.97%) (Table 1). To further validate the reliability of the urine-based test, we assessed its agreement with the blood-based test. The overall agreement rate was 99.93% (95% CI: 99.79%–100.00%), with a Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.998 (95% CI: 0.986–1.000), indicating near-perfect concordance between the two tests (Table 2).

Usability and acceptability

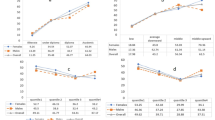

Of the 1,066 questionnaires collected, 857 (80.39%) untrained participants achieved high scores, while 209 (19.61%) scored low. The proportion of HIV-infected individuals with high scores was slightly higher than that of high-risk or general population participants, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.11). Younger participants (18–50 years) demonstrated significantly better comprehension of the IFU compared with older participants (≥ 51 years) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, females demonstrated a better understanding of the IFU compared to males (p < 0.001). Participants with higher education and a medical background scored higher than those without such qualifications (p < 0.001; Table 3).

According to questionnaire data, 98.21% (1,047/1,066) of untrained participants thought they could conduct urine-based HIVST independently (Fig. 2a), and 97.84% (1,043/1,066) reported a positive experience with urine-based HIVST (Fig. 2b). The survey results revealed relatively high error rates for three specific questions: the appropriate time frame for using the reagent after opening the package (163/1,066, 15.29%), the correct handling of invalid test results (235/1,066, 22.05%), and the correct response to a positive test result (189/1,066, 17.73%). In contrast, error rates for all other questions were below 5.00% (Fig. 2c).

Usability evaluation of self-testers who could independently complete the urine-based HIVST. Acceptability of urine-based HIVST, questionnaire survey results, and interpretation of contrived test devices. (a. Number of self-testers who felt they could conduct the test independently; b. Self-testers’ opinions regarding urine-based HIVST before self-testing; c. Error rate per question in questionnaire; d. Error rate in interpreting contrived test devices).

Ultimately, 1,064 individuals interpreted results by observing contrived test devices. Most of the self-testers correctly identified positive results (1,057/1,064), negative results (1,041/1,064) and invalid 2 (1,059/1,064) results. However, error rate in weakly positive and invalid 1 results were high which were 6.86% (73/1,064) and 15.04% (536/1,064), respectively (Fig. 2d).

The total agreement rate between self-testers and laboratory professionals was 99.78% (95% CI: 99.39%−100.00%), with a kappa value of 0.995 (95% CI: 0.965–1.000; Table 4). Observation by professionals revealed that 93.04% (1,003/1,078) of self-testers performed the HIVST correctly, while 6.86% (74/1,078) performed it with minor errors. One self-tester succeeded after a repeated test. Additionally, professionals identified that 34 of 1,078 (3.16%) self-testers did not meet the required sample volume, and 41 of 1,078 (3.80%) did not adhere to the required testing duration. For the self-testers performing HIVST at home versus in clinical settings, 5 positive results and 102 negative results were detected in both environments. The agreement rate between these two testing locations was 100.00%, with a Cohen’s kappa value of 1.00.

Discussion

In this study, based on data from multiple centers across China involving diverse populations in real-world settings, the urine-based HIVST method demonstrated satisfactory performance, with a sensitivity of 99.44% (95% CI: 97.78–99.90%) and a specificity of 100.00% (95% CI: 99.54–100.00%). Additionally, the urine-based HIVST showed good usability and applicability, as participants were able to understand and perform the test with minimal difficulty. The high level of consistency between self-testers and laboratory professionals further supports the conclusion that urine-based HIVST is simple to conduct and can be reliably performed outside of clinical settings. Previous studies conducted in China have also confirmed the high accuracy and acceptability of urine-based HIVST, and this testing method has already been included in the Chinese national HIV testing technical guidelines (2020) and received prequalification from the WHO21,22,23. Importantly, the performance of the urine-based test kits meets WHO-recommended criteria for HIV self-testing, which emphasize accuracy and reliability when used by lay persons, the ability to conduct testing in a convenient and confidential manner, and the provision of clear IFU24. This highlights their potential for large-scale implementation in resource-limited settings through global health initiatives.

Two HIV-infected individuals were not detected by the urine kit, whereas one HIV-infected individual was not detected by the blood kit. The performance of the urine assay may be influenced by characteristics of the kit itself as well as specimen quality25. For example, failure to collect midstream urine can affect test accuracy due to potential contamination from urethral inflammation. Other influencing factors include not using first-morning urine and various physical conditions26. Of note, one untreated AIDS participant with fungal infectious stomatitis tested negative on both urine and blood tests. This type of case is extremely rare worldwide27. Prior research indicates that, in advanced AIDS, CD4+ T-cell depletion can impair B lymphocyte activation, leading to low serum antibody titers and occasional false-negative antibody results28. Among individuals on ART, detection rates decreased for both urine and blood, but the decline was greater for urine29. Because urinary HIV-specific IgG levels are much lower than those in serum and depend on renal transudation, ART-related reductions in viral replication and antibody production further limit the amount of IgG entering the urine, thereby pushing antibody concentrations below assay detection thresholds and substantially reducing the detectability of antibodies in urine30. These findings indicate that the diagnostic performance of urine-based HIV tests can be influenced by both patient status and procedural factors, underscoring the need for proper sample collection and consideration of clinical context when interpreting results. Accordingly, self-testers should interpret negative results with caution; as stated in the IFU, individuals with recent or ongoing high-risk exposures should repeat testing at appropriate intervals or seek confirmatory testing and counseling at a healthcare facility to enable early detection and prevention.

In the feedback of the questionnaire, the proportion of HIV-infected individuals with high scores was higher than that of other people in our study. This may be due to the fact that people living with HIV are often more familiar with HIV-related information, which likely enhanced their ability to understand the urine-based HIVST. However, disparity of scores in individuals with different infection status/risk of HIV infection had no statistical significance, and the relationship between HIV infection status/risk and the ability to comprehend the IFUs of the urine kit warrants further investigation. Age was significantly associated with HIVST usability (p < 0.001), with younger participants attaining higher scores than those ≥ 51 years. This pattern may reflect greater comfort with digital/visual instructions and the handling of self-testing devices among younger adults, whereas older adults may encounter difficulties with lengthy text or interpretation of visual cues required by the procedure31,32. Participants with higher educational attainment or medical backgrounds achieved higher IFU-comprehension scores, plausibly due to stronger literacy and health knowledge. Conversely, participants with lower education may find lengthy or technical IFUs harder to understand, potentially affecting usability and test accuracy33. To improve usability in lower-literacy groups, strategies such as simplifying IFU language, incorporating clear visual aids, embedding short instructional videos (e.g., via QR codes), and user-testing with low-literacy populations are recommended34,35. Additionally, females tended to score higher than males, which may be attributed to the generally more meticulous nature of females and their more sincere attitudes towards participating in the on-site trial36.

Analysis of the questionnaire showed high error rates in questions 4, 9, and 10. Question 4, about the test duration, was often misunderstood—some participants confused it with the time to read the result. This may be due to skimming the instructions or low education levels. Questions 9 and 10, which asked about handling invalid results and proper disposal, were also frequently answered incorrectly. Since these were multiple-choice, some participants only chose one option, possibly due to unclear instructions. In the results of the contrived test devices, weakly positive cases had high error rates. This may be because the test (T) line was faint, making it hard for users to judge. Errors in recognizing invalid results were also common, likely due to confusion between the control (C) and T lines. To improve this, instructions in the IFU should be clearer, and adding a QR code linking to a video or interactive guide could help users better understand the process35. When comparing the questionnaire results with actual testing, fewer mistakes were seen in practice. This suggests that self-tests are simple enough for most users to perform correctly. While small differences in sample volume (e.g., using two or four drops) didn’t usually affect results, it’s still important to stress the correct volume in both instructions and videos. Some users also judged the result too early, before the C and T lines fully appeared. A clear reminder about the correct time to read the result should be added to the IFU.

This study has several limitations. First, information on participants’ residential settings (urban or rural) was not collected, preventing evaluation of potential differences in usability or acceptability. Second, children and adolescents were not included, limiting generalizability to younger populations. Third, the exact timeframe for returning the HIVST kits to the clinic was not recorded; therefore, the potential influence of timing on result accuracy cannot be entirely ruled out. Future research should explore the integration of urine-based HIVST into broader HIV prevention and care frameworks, including its potential use as a routine self-testing tool during the follow-up phase of long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis, as well as in partner services, cost-effectiveness analyses, and real-world clinical outcomes among untreated individuals after self-testing37,38,39.

Conclusion

The urine-based HIVST demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy, excellent usability, and strong agreement between self-testers and professionals. It serves as a valuable complement to existing HIVST approaches, expanding the testing toolbox beyond oral fluid- and blood-based methods. Owing to its non-invasive nature, simplicity, and privacy, it can better accommodate the diverse needs and preferences of different populations. Collectively, these findings support urine-based HIVST as a practical, acceptable, and scalable strategy to expand HIV testing coverage, facilitate the early identification of undiagnosed infections, and accelerate progress toward achieving the first 95 target of the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals in China and comparable settings worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due patient privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS. Understanding fast-track: accelerating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. (2014). https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf:2014 [Accessed 12 October 2024].

World Health Organization. HIV and AIDS. https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (Accessed 24 September 2024).

He, N. Research progress in the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in China. China CDC Wkly. Vol. 3, 48: 1022–1030. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2021.249 (2021).

World Health Organization. WHO recommends HIV self-testing – evidence update and considerations for success. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.36 [Accessed 12 October 2022].

Zhang, Y., Johnson, C. C., Nguyen, V. T. T. & Ong, J. J. Role of HIV self-testing in strengthening HIV prevention services. The Lancet HIV. 11 (11), e774–e782. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(24)00187-5 (2024).

World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV Self-Testing and Partner Notification: Supplement To Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services (World Health Organization; December, 2016).

Dovel, K. et al. Effect of facility-based HIV self-testing on uptake of testing among outpatients in malawi: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Global Health. 8 (2), e276–e287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30534-0 (2020).

Amstutz, A. et al. Home-based oral self-testing for absent and declining individuals during a door-to-door HIV testing campaign in rural Lesotho (HOSENG): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 7 (11), e752–e761. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30233-2 (2020).

Pant Pai, N. et al. Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high- and low-risk populations: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 10 (4), e1001414. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001414 (2013).

Witzel, T. C. et al. Comparing the effects of HIV self-testing to standard HIV testing for key populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 18 (1), 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01835-z (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Impact of providing free HIV self-testing kits on frequency of testing among men who have sex with men and their sexual partners in china: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 17 (10), e1003365. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003365 (2020).

Shrestha, R. K. et al. Estimating the costs and cost-effectiveness of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men, united States. J. Int. AIDS. Soc. 23 (1), e25445. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25445 (2020).

Nichols, B. E. et al. Economic evaluation of facility-based HIV self-testing among adult outpatients in Malawi. J. Int. AIDS. Soc. 23 (9), e25612. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25612 (2020).

World Health Organization. HIV rapid diagnostic tests for self-testing. (2017). https://marketbookshelf.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/HIV-Rapid-Diagnostic-Tests-for-Self-Testing_Landscape-Report_3rd-edition_July-2017.pdf [Accessed 20 October 2025].

Kalibala, S. et al. Factors associated with acceptability of HIV self-testing among health care workers in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 18 (Suppl 4), S405–S414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0830-z (2014).

Lippman, S. A. et al. Ability to use oral fluid and fingerstick HIV self-testing (HIVST) among South African MSM. PloS One. 13 (11), e0206849. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206849 (2018).

Steehler, K. & Siegler, A. J. Bringing HIV Self-Testing to scale in the united states: a review of Challenges, potential Solutions, and future opportunities. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57 (11), e00257–e00219. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00257-19 (2019).

Balakrishnan, P. et al. Oral fluid versus blood in HIV self-testing: A step towards 95-95-95 targets of the UNAIDS? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 113 (1), 116867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2025.116867 (2025).

Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. World’s first HIV urine self-test approved for marketing. (2019). https://www.most.gov.cn/gnwkjdt/201910/t20191024_149514.html [Accessed 18 October 2025]. (In Chinese).

World Health Organization. HIV SELF TEST BY URINE-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) type-I urine antibody diagnostic kit (colloidal gold). (2025). https://extranet.who.int/prequal/vitro-diagnostics/0544-005-00 [Accessed 19 October 2025].

Zhang, C. et al. Accuracy of the self-administered rapid HIV urine test in a real-world setting and individual preferences for HIV self-testing. China CDC Wkly. 7 (2), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2025.011 (2025).

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Guideline for Detection of HIV/AIDS. (2020). edition https://ncaids.chinacdc.cn/zxzx/zxdteff/202005/W020200522484711502629.pdf (2020) [Accessed 20 December 2024].

Lu, H. et al. Diagnostic performance evaluation of urine HIV-1 antibody rapid test kits in a real-life routine care setting in China. BMJ open. 14 (2), e078694. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078694 (2024).

World Health Organization. WHO recommends HIV self-testing – evidence update and considerations for success. (2019). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.36 [Accessed 10 December 2024].

Street, J. M., Koritzinsky, E. H., Glispie, D. M., Star, R. A. & Yuen, P. S. Urine exosomes: an emerging trove of biomarkers. Adv. Clin. Chem. 78, 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acc.2016.07.003 (2017).

LaRocco, M. T. et al. Effectiveness of preanalytic practices on contamination and diagnostic accuracy of urine cultures: a laboratory medicine best practices systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 29 (1), 105–147. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00030-15 (2016).

Yan, S. et al. A rare case of an HIV-seronegative AIDS patient with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. BMC Infect. Dis. 19 (1), 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4143-8 (2019).

Kaw, S. et al. HIV-1 infection of CD4 T cells impairs antigen-specific B cell function. EMBO J. 39 (24), e105594. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2020105594 (2020).

Connell, J. A. et al. Preliminary report: accurate assays for anti-HIV in urine. Lancet 335 (8702), 1366–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(90)91245-6 (1990).

Wyatt, C. M. et al. Changes in proteinuria and albuminuria with initiation of antiretroviral therapy: data from a randomized trial comparing Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine versus abacavir/lamivudine. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 67 (1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000245 (2014).

Zhang, X., Yuan, Y. & Jiang, J. Digital health literacy among older adults in china: a cross-sectional study on prevalence and influencing factors. Front. Public. Health. 13, 1661177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1661177 (2025).

Zeleke, E. A., Stephens, J. H., Gesesew, H. A., Gello, B. M. & Ziersch, A. Acceptability and use of HIV self-testing among young people in sub-Saharan africa: a mixed methods systematic review. BMC Prim. Care. 25 (1), 369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02612-0 (2024).

Chaniaud, N., Megalakaki, O., Capo, S. & Loup-Escande, E. Effects of user characteristics on the usability of a Home-Connected medical device (Smart Angel) for ambulatory monitoring: usability study. JMIR Hum. Factors. 8 (1), e24846. https://doi.org/10.2196/24846 (2021).

Kurth, A. E. et al. Accuracy and acceptability of oral fluid HIV Self-Testing in a general adult population in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 20 (4), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1213-9 (2016).

Buch, S. V., Treschow, F. P., Svendsen, J. B. & Worm, B. S. Video- or text-based e-learning when teaching clinical procedures? A randomized controlled trial. Advances Med. Educ. Practice. 5, 257–262. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S62473 (2014).

Lobato, L. et al. Impact of gender on the decision to participate in a clinical trial: a cross-sectional study. BMC public. Health. 14, 1156. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1156 (2014).

Indravudh, P. P. et al. Effect of door-to-door distribution of HIV self-testing kits on HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy initiation: a cluster randomised trial in Malawi. BMJ Global Health. 6 (Suppl 4), e004269. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004269 (2021).

Indravudh, P. P. et al. Pragmatic economic evaluation of community-led delivery of HIV self-testing in Malawi. BMJ Global Health. 6 (Suppl 4), e004593. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004593 (2021).

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on differentiated HIV testing services. (2024). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240096394 [Accessed 22 October 2025].

Funding

This study was supported by the Project of China National Key Laboratory of Intelligent Tracking and Forecasting for Infectious Diseases, the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. L244069), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 72474226 and 71974199).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZM-N: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. ZJ-H: Validation, Methodology, Investigation. X Z& Y J: Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. QY-Z: Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis. DS-H& P G: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. C J: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, M., He, Z., Zhang, X. et al. Urine-based HIV-1 self-testing in China: A cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy and usability study. Sci Rep 15, 44610 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28286-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28286-x