Abstract

Metal detection plays an important role in applications ranging from security to industrial quality control. This work presents a novel ground-less circular patch resonator which behaves as an open stub, engineered for high-sensitivity detection of metallic objects. The key innovation lies in utilizing electric field coupling between the stub’s top surface and nearby metallic targets. The detection is achieved by monitoring changes in the transmission coefficient. The proposed design offers two key advancements by extending detection range up to 8 cm and selective sensitivity exclusively to metallic materials by remaining unresponsive to dielectric objects. Experimental results show that as the distance between the metallic object and the sensor decreases, the resonance coupling becomes stronger, demonstrated by a resonance frequency shift and dip of approximately -10 dB in the transmission coefficient. The sensor is also capable of “see-through” metal detection behind dielectric barriers, and its selective sensitivity to metallic materials helps minimize false responses from non-metallic objects. This approach allows for the detection of cracks in metallic objects and applications involving ground penetration radar (GPR) systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal detection is a critical technology with applications in security screening, industrial automation, archaeology, and food safety1,2. Conventional methods, such as inductive proximity sensors and eddy current detectors, face limitations such as shallow penetration depth, susceptibility to environmental noise, and poor resolution for small or deeply embedded objects3,4,5. Historically, metal detection relied on methods such as beat-frequency oscillators (BFO) and pulse induction (PI), which analyze frequency changes or inductive field responses caused by metallic objects6,7. However, these methods struggle with sensitivity and accuracy requirements, particularly for low-conductivity metals. Microwave sensing has emerged as a robust alternative, operating at higher frequencies (1–100 GHz) to enable non-invasive detection and deeper penetration8,9. By analyzing perturbations in microwave signals (e.g., scattering parameters, resonance frequency shifts), these systems achieve high precision. Recent advances in miniaturized antennas, metamaterials, and machine learning have further expanded their applicability10,11.

Microwave sensing utilizes electromagnetic interactions between waves and conductive materials. Antenna theory offers the foundation for the design of antennas and understanding wave propagation, elucidating how metallic objects affect scattering parameters. For example, split-ring resonators (SRR) operating at 2.45 GHz are used to detect buried metals in the soil12, while synthetic aperture radars at 350 GHz facilitate millimeter wave imaging for security applications13. A microwave split-ring resonator sensor for real-time, non-contact, and selective measurement of water, alcohol, and sugar concentrations using multi-harmonic spectral analysis14,15.

The proximity coupling in microwave resonators, especially through open stubs transitioned to SRR, has emerged as a promising technique. SRR characterized by their strong resonance behavior, enhance sensitivity to environmental variations16. Transitioning from an open stub to an SRR improves field confinement and resonance control, increasing the system’s sensitivity to mutual coupling with nearby metallic objects17,18,19. This coupling redistributes current and modifies the resonator’s input impedance, altering transmission characteristics, and enabling detection through measurable changes in the transmission coefficient. Sensitivity can be further enhanced by optimizing the SRR geometry20,21,22. However, since metal sensing is achieved through the perturbation of microstrip fields, these sensors also exhibit sensitivity to dielectric samples, sometimes making it challenging to distinguish between metal and dielectric materials22. In contrast, our proposed sensing scheme relies on proximity coupling with the metal object, making it unresponsive to the presence of dielectrics. The concept of “see-through dielectric wall” is illustrated in Fig. 1. When a metallic object is positioned beneath the circular patch, it completes the resonant path, resulting in a sharp Lorentzian resonance at a frequency determined by the metal’s proximity. As demonstrated in the following sections, the resonance depth and frequency can be used to characterize the object’s distance from the dielectric wall.

Microwave sensing technology is adoptive in diverse fields from archaeology to security23,24. In industrial safety and automation, microwave sensors are crucial for detecting metal contaminants in food products and identifying surface cracks in metallic structures20. Machine learning techniques have been integrated to improve the detection and characterization of internal defects in composite materials and surface cracks in metals25. For example, waveguide probes combined with SRR have been developed to detect surface cracks in metallic surfaces by analyzing changes in resonance frequency and scattering parameters18,19,26. These innovations highlight the synergy between hardware advancements, such as compact resonant structures, and software-driven analytics, enabling real-time detection in complex scenarios27.

Microwave resonators incorporating SRR have shown significant improvements in quality factor (Q-factor), improving detection capabilities compared to traditional resonators26. Coupling-based sensing has also been applied in moisture detection, biomedical sensing, and material characterization28,29. For example, implantable antennas that use coupling-based techniques monitor physiological parameters with high sensitivity, enabling applications such as glucose monitoring and pressure detection9,30,31.

Despite progress, challenges remain, including signal attenuation in conductive media (e.g. wet soil), interference from nonmetal clutter, and high-power demands at millimeter-wave frequencies. Researchers are addressing these limitations through ultra-wideband (UWB) sensors for improved penetration and multi-static radar configurations to enhance spatial resolution32. Using proximity coupling in microwave resonators, detection sensitivity and accuracy can be significantly improved for a wide range of critical applications, including the detection of surface cracks in metallic structures.

Design of circular patch resonator

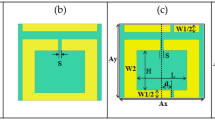

The design of circular patch resonator is provided in the Fig. 2. The patch stub metal proximity sensor consists of a planar dielectric substrate on Rogers RT/Duroid 6002, with a width of \(p_x = 60\) mm and a length of \(p_y = 64\) mm. The circular patch has a diameter of \(d = 54\) mm and is placed above the probed metal surface at a certain height h (also known as lift-off distance). The microstrip transmission line has a width of \(t = 2\) mm, while the ground conductor has a width of \(w = 6\) mm. The ground conductor partially covers the transmission line in the top plane and remains hollow beneath the circular patch. The feed-line connecting the patch to the transmission line, has a length of \(s = 6\) mm. The dielectric substrate has a thickness of 0.762 mm, and the metal layer has a thickness of 18 \(\upmu\)m. The substrate material is selected to provide a balance between effective field confinement and extending the electromagnetic field into the surrounding environment, thereby enhancing coupling with nearby metallic objects. The thickness of the substrate offers mechanical stability while maintaining excellent electromagnetic properties.

It is important to highlight that the design features a ground-less configuration, producing a highly localized electric field that couples selectively to metallic objects while remaining insensitive to dielectrics. A circular geometry was chosen over other shapes for its rotational symmetry, compact footprint, simplified mode structure, and compatibility with the stub arrangement, ensuring uniform sensitivity. The dimensions were optimized to enhance the sensitivity of the sensor for detecting small metallic objects. The proposed microwave resonator detects metals by exploiting the interaction between its electromagnetic fields and nearby metallic surfaces, where the resonant electric field couples with the surface currents induced on the circular patch, leading to measurable perturbations in the microwave transmission characteristics.

Simulation results

We performed full-wave electromagnetic simulations using a finite element method (FEM)-based simulation platform, to rigorously model the interaction of microwave fields with conductive structures. The simulation provided high-fidelity analysis of field distributions, current densities, and scattering parameters (S-parameters) for the designed geometries.

In the absence of metallic objects, the resonator operates with minimal resonant coupling effects. The circular patch section without a ground-conducting plane has the electric field distributed around the circular patch as shown in Fig. 3a. This field distribution ensures efficient energy transfer between the input and output terminals. Furthermore, the transmission properties of the resonator were examined in the presence of external metallic objects, as depicted in Fig. 3b. Three distinct scenarios were evaluated: a metallic backplane configuration resonating at approximately 380 MHz, a metallic plate positioned at \(h = 1~\text {mm}\) resonating around 1.22 GHz, and a metallic plate at \(h = 10~\text {cm}\) exhibiting shallower dips, indicating diminished interaction with greater distance. These observations highlight the resonator’s responsiveness to the proximity and presence of metallic objects.

Here, we examine the effect of perturbation due to proximity of metallic object close to the circular patch resonator. The electric and magnetic field distributions are shown in Fig. 4, where the coupling-induced surface charge from the metallic object under test perturbs the electric field. When a planar metallic object approaches the resonator, the electric field from the circular patch couples to the metallic object via capacitive coupling. This interaction induces opposing surface charges on the circular patch and the metallic object, effectively forming an electrical dipole. The strength of this interaction is characterized by a mutual capacitance effect, which depends on the distance \(h\) between the resonator and the metallic sheet.

Electric field vector field (left) and magnetic field vector field (right) distributions across the cross sectional plane for different distances \(h\) between the resonator and the metallic sheet below the substrate i.e., \(h = 1\,\text {cm}\), \(h = 2\,\text {cm}\), and \(h = 3\,\text {cm}\). The arrow lengths for both the electric field (( E ), in V/m) and magnetic field (( H ), in A/m) are normalized to reflect the relative magnitude of the field strength at each point.

The electric and magnetic field coupling, and the corresponding dipole formation are illustrated in Fig. 4. As an example, at a distance of \(h = 1\, \text {cm}\), the electric and magnetic field coupling is strong, resulting in a significant accumulation of surface charge on the metallic sheet and creating a pronounced dipole. This strong coupling corresponds to a high mutual capacitance between the resonator and metal object. As the distance increases to \(h = 2\, \text {cm}\), the resonant coupling decreases. Finally, at \(h = 3\, \text {cm}\), the resonant coupling decreases further. These near-field coupling characteristics highlight the resonator’s sensitivity to metal proximity. At shorter distances, the strong coupling substantially alters the resonator’s impedance and shifts its resonance frequency. In contrast, at larger distances, the weaker coupling results in minimal variation in the surrounding electric field. These effects serve as the basis for detecting metallic objects based on their proximity to the resonator.

Transmission coefficient \(S_{21}\) due to proximity with metallic object at various distances \(h\) at longer distances (a) cm scale and shorter distances (b) mm scale. (c) Variation in the dip of \(S_{21}\) with respect to distance \(h\). (d) Corresponding shift in resonant frequency with distance \(h\).

The simulated transmission characteristics of the microwave resonator in the context of metal proximity detection are provided in Fig. 5a, b. Figure 5a, b presents the transmission coefficient, \(S_{21}\), in dB as a function of frequency for different distances of the metal object under test from the resonator. As the object moves closer (e.g., 10 mm), the resonance dip deepens significantly, indicating stronger coupling and variation in impedance characteristics of a circular patch stub resonator. As the distance increases, the resonance dip becomes shallower, demonstrating reduced interaction between the resonator and the metal object.

Figure 5c quantifies the minimum value of a resonance dip as a function of distance from the spectral characteristics of \(S_{21}\) in Fig. 5a. The results show that at shorter distances, the transmission loss is more pronounced because of strong coupling with the nearby metal object. As the object moves farther away, the transmission dip decrease shows a weaker coupling. Figure 5d tracks the resonant frequency at which the minimum \(S_{21}\) occurs as a function of distance. Initially, as the metal object gets closer, the resonant frequency shifts to lower frequencies, indicating an increase in effective capacitance as a result of strong field interaction. Beyond a certain distance, the resonant frequency begins to shift to higher frequencies.

The depth of the resonance dip and the frequency shift serve as key indicators for proximity detection, establishing it as an effective mechanism for metal detection and detection of associated metallic cracks.

The input impedance of a circular patch open-circuit stub is difficult to determine analytically due to complex electromagnetic interactions, including non-uniform current distributions, fringing fields, and higher-order mode excitations. Furthermore, the ground plane is missing below the circular patch, and the fringing fields couple directly to the metallic object under test. As a result, numerical methods such as full-wave electromagnetic simulations are utilized to determine the input impedance of the resonator stub.

Figure 6 presents the simulated input impedance (\(Z_{in}\)) as a function of frequency for different distances of the metal object. The inset diagram illustrates the circular patch with an inset feed, where the impedance of the stub is evaluated. The variation in impedance highlights the sensitivity of the resonance behavior to the proximity of a metal object. Specifically, the resonance frequency shifts as the distance from the object under test varies. Moreover, the plot in Fig. 6 focuses the lower values of \(\Re ({Z_{\text {in}}})\) near unity, which determines the condition for maximum power transfer through the inset feed. In particular, the smallest input impedance value \(\Re ({Z_{\text {in}}}\)) approaching unity is observed for a closer distance at \(h = 0.5\) cm, indicating a stronger resonant coupling between the circular patch and the metallic object.

Next, we evaluate the sensor’s sensitivity to specific features of metallic objects, including their size and the presence of potential cracks within metal sheets. It is noteworthy that various microwave sensing approaches have been reported for identifying such metallic characteristics, particularly targeting crack or flaw detection in metal structures33. This analysis also offers a quantitative perspective on the sensor’s detection limits. Figure 7a shows the variation in transmission coefficient due to the proximity of a metallic sheet with various cross-sectional areas (A). The distance between the detector and the sheet is fixed at h = 2 cm. The areas range from 100 \(\text {mm}^2\) to 10,000 \(\text {mm}^2\). The results indicate that as the cross-sectional area increases, the transmission coefficient varies, showing distinct resonant dips around 1.45 GHz, with the depth and width of the dips influenced by the area of metallic sheet. This parametric analysis highlights the sensor sensitivity to background metal objects.

Figure 7b illustrates the variation in the transmission coefficient caused by small cracks on a wide metallic sheet. The sensor exhibits clear sensitivity to such cracks, and to further enhance this sensitivity, the lift-off distance was reduced to h = 0.5 cm. The crack width (wd) was varied from 1 mm to 5 mm and compared with the sensor’s response to an intact sheet. The results show that both the presence and width of the crack have a significant impact on the transmission coefficient, with narrower cracks (1 mm) producing deeper and sharper resonance dips around 1.45 GHz, whereas wider cracks yield a smoother spectral response. These observations demonstrate the resonator’s capability to shift the resonance frequency and improve crack detection sensitivity. Overall, the findings indicate that the cross-sectional area and the presence of cracks in metallic sheets can be effectively detected and characterized by monitoring changes in the transmission coefficient over the frequency range.

Experimental results

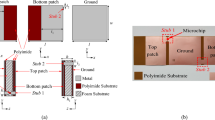

The performance of the proposed resonator sensor is experimentally verified by fabrication and measurement with proximity testing in various conditions. Figure 8a shows that the sensor is placed in the closed vicinity a metallic sheet at distance \(h\). The sensor response is measured to detect changes in the transmission coefficient (\(S_{21}\)). A vector network analyzer (VNA) was used to measure the transmission coefficient (\(S_{21}\)) of the sensor. Initially, \(S_{21}\) was measured in the absence of any object near the sensor to establish a baseline reference. Subsequently, a metallic sheet was placed at varying distances \(h\), ranging from 1 cm to 8 cm with increments of 1 cm, and the corresponding \(S_{21}\) values were recorded to observe the effect of proximity of metal object on the sensor’s response.

To evaluate the see-through-wall capabilities, a piece of cardboard was placed near the sensor, and the transmission coefficient (\(S_{21}\)) was measured as shown in Fig. 8b. Subsequently, the see-through-wall performance was evaluated by positioning the cardboard at a fixed distance of 1 cm from the sensor, while a metallic sheet was maintained at a constant 3 cm distance. See-through-wall sensing plays a vital role in Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) applications, facilitating the detection of buried objects.

The transmission coefficient \(S_{21}\) was measured under these diverse conditions to analyze the combined influence of metallic and non-metallic materials on the sensor’s response. The measured \(S_{12}\) response provided in Fig. 9a exhibits a clear trend as the distance \(h\) between the sensor and the metallic object under test is varied. It is worth mentioning that a discrepancy exists between the experimental and simulated spectral results in terms of resonance frequency. For instance, for the metal sheet placed at a distance of h = 1 cm, the simulations indicate a resonance near 1.45 GHz, whereas microwave measurements show a resonance around 800 MHz. We believe that these variation are primarily due to additional capacitive coupling introduced by the metallic connectors positioned near the adjacent ports, as shown in Fig. 8b. Implementing appropriate shielding can effectively mitigate these spurious coupling effects. As the metallic sheet approached the sensor, the transmission coefficient (\(S_{12}\)) showed a significant resonant dip as shown in Fig. 9b, indicating increased coupling between the electric field of the resonator and the metallic object. Furthermore, the Fig. 9c provides the influence on resonant frequency with the distance distance \(h\). This measured response is consistent with the simulated response reported earlier in Fig. 5a, b.

The Fig. 10 presents the experimental setup and corresponding measurements for crack detection in a metallic sheet using transmission coefficient analysis. The inset shows the metallic sheet with cracks of varying widths (wd), positioned 5 mm below the sensor. The measured transmission coefficients (S21) are plotted for crack widths of 1 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm, and compared against the no-crack case. The results indicate that the presence of cracks has a clear impact on the S21 response, with even a small crack of 1 mm width being detectable.

Measured transmission coefficients (\(S_{12}\)) under see through wall detection condition i.e., sensor next to dielectric plastic sheet only at 1 cm distance and dielectric sheet with the metal sheet at 2 cm distance in the background as shown in Fig. 8c.

Figure 11 shows the influence on the sensor’s response when a dielectric surface is introduced next to the resonator. When a non-metallic object (cardboard) was placed near the sensor, the \(S_{21}\) values showed negligible variation in comparison to no neighbouring object. This highlights the sensor’s selective sensitivity to metallic objects. Similarly, Fig. 11 shows the see-through wall capabilities of the sensor with the metallic sheet positioned at 3 cm and the cardboard at 1 cm. The resonance is still strong in \(S_{21}\) due to coupling with the metallic sheet behind the cardboard wall. By transmitting electromagnetic waves and analyzing the resulting perturbations, subsurface structures can be effectively examined. This technique is widely applied in archaeology to uncover ancient structures, in civil engineering to inspect foundations and pipelines, and in military operations to detect landmines.

These experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed sensor in detecting metallic objects or cracks in the metallic objects and its ability to differentiate between metallic and non-metallic materials based on changes in the transmission coefficient (\(S_{21}\)).

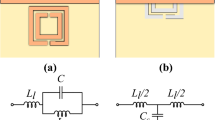

(a) Equivalent circuit representation of spectral response of a single open-circuited stub resonator for metal detection application. (b) Comparison between S21 parameter (transmission coefficient) and the analytical model. (c) The analytical model S21 responses are evaluated for varying resistance ( \(R_1\) ) (from 1\(\Omega\) to 50\(\Omega\)) over the same frequency range.

Equivalent circuit model and transfer matrix representation

To gain physical insight into the operating principle of the proposed stub-based metal sensor, an equivalent lumped-element circuit is developed and expressed in the transfer-matrix (ABCD) formalism. The sensing element is a single open-circuited stub attached to the center of a transmission line of characteristic impedance \(Z_0\) and electrical half-length d/2. The open stub is modelled by a series \(R_1\)–\(L_1\)–\(C_1\) branch whose series impedance is mapped to an equivalent shunt admittance when connected to the main line.

The transmission-line half-sections are each represented by the two-port transfer matrix

where \(\beta\) is the propagation constant and \(Y_0=1/Z_0\). The open-stub (series \(R_1,L_1,C_1\)) appears as a shunt admittance

and its two-port transfer matrix (shunt element) is

The total transfer matrix of the single-stub configuration is the cascade of the left line, the stub, and the right line:

For ports matched to \(Z_0\), the forward transmission coefficient is obtained from the ABCD parameters as

Because \(Y_i(\omega )\) contains the series RLC branch, the position, depth and bandwidth of the observed transmission notch are direct consequences of the chosen \(R_1,L_1,C_1\) values and the electrical length d of the host line.

Figure 12b shows a comparison of \(S_{21}\) spectral responses obtained from the equivalent-circuit transfer-matrix model above and full-wave electromagnetic simulation of the physical microstrip stub. Table 1 provides the parameters that define the electrical and physical properties of the microstrip line and its stub, used to compute the S21 spectral response. The circuit model accurately predicts the resonance frequency and the general notch shape for the resonance. Overall, the equivalent circuit based transfer-matrix method provides a better understanding for underlying physical phenomenon due to coupling with nearby metallic targets. Furthermore, the transmission spectra for the analytical model are plotted for \(R_1\) values ranging from 1 to \(50~\Omega\), as shown in Fig. 12c. A smaller resistance results in lower losses and a higher quality factor (Q), leading to a sharper resonance and a deeper notch. As \(R_1\) increases, losses rise, the resonance broadens, and the notch depth decreases. This highlights \(R_1\) as a critical parameter for tuning the sensor’s sensitivity and bandwidth.

Benchmarking analysis

In the past, numerous microwave and millimeter-wave (MMW) techniques have been proposed for locating metallic features, with a major focus on detecting cracks or flaws in metal components33. There are a number of non-distructive techniques methods in the range of microwave and millimeter-wave for detecting surface-breaking cracks in metals.

The ideal metal sensor should possess features such as versatility and effectiveness across diverse applications. High lift-off capability is critical, allowing non-contact detection over uneven or inaccessible surfaces, enhancing safety and practicality in industrial or structural inspections. See-through-wall detection is another standout feature, enabling the sensor to identify hidden metal objects through non-metallic barriers. Additionally, sub-millimeter crack detection ensures the sensor can identify both fine and moderate defects. Lastly, a compact, non-intrusive design improves portability and ease of deployment.

Table 2 summarizes microwave-based metal sensing methods, primarily developed for detecting small-scale fatigue cracks but applicable to broader metal detection tasks due to their reliance on electromagnetic coupling and resonant field perturbations. Far-field techniques, such as those in33 (26.5–40 GHz) and34 (40 GHz), employ rectangular waveguide apertures or cutoff-cavity probes for precise open-space applications, though they are limited by lift-off distances of 1–9 mm. Resonant coupling approaches, including35 (0.8 GHz spiral resonator),36 (1.5–3 GHz split-ring resonator), and37 (3.5–9.5 GHz CSRRs), provide high sensitivity but require minimal lift-off (0–0.2 mm). Meanwhile, resonant scattering methods, as in38,39, uses RFID sensor tags to detect defects in planar metal sheets. The approach involves examining the surface and remotely monitoring the backscattered signal using a reader. These RFID techniques rely on detecting perturbations in the RFID tag’s backscattered signal, that is caused by a crack that alters the current distribution around the tag’s antenna. The drawback is that these method assume that the crack’s location is either known in advance or will develop in close proximity to the tag.

Compared to existing methods, our ground-less sensor offers a unique advantage with its 5 mm to 8 cm lift-off range and through-wall detection capability, significantly exceeding the 0–9 mm lift-off of other approaches. This makes it particularly suited for non-contact and concealed metal detection. In contrast to many probes that require near-contact scanning and have strict polarization constraints such as RFID sensor tags, our circular patch resonator is largely orientation-independent and remains effective at moderate lift-off distances. Its consistent dip in \(S_{21}\) deeper than -10 dB range and minimal sensitivity to dielectric barriers enable reliable detection of various metallic objects. Furthermore, the ground-less architecture enhances portability compared to bulkier waveguide or RFID-based probes, making it one of the most versatile options for modern non-destructive testing.

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed a circular patch microwave resonator with an open-circuit stub for metallic object detection, where the sensing mechanism is based on variations in the transmission coefficient (\(S_{12}\)) due to electric field coupling with nearby metallic objects. Experimental results confirm the feasibility of the design, with measurable resonance changes observed as metallic targets approach the resonator. While detectable responses extend up to 8 cm, the practical sensitivity is strongest within approximately 1 cm. Moreover, although the concept suggests potential applicability in ground-penetrating radar (GPR), our proof-of-concept only involved detection through a cardboard barrier, and therefore such claims remain preliminary until further subsurface evaluations are conducted. Finally, the present study primarily relies on the depth of the \(S_{12}\) resonance dip as a detection metric, and future work could strengthen robustness by considering frequency shifts or multi-frequency analysis. Overall, the proposed sensor demonstrates a promising step toward compact and scalable microwave resonators for metallic object detection, with clear opportunities for refinement in sensitivity, detection range, and metric robustness.

Data availability

All data required to evaluate the findings of this work is available in the presented paper. Additional data related to this work may be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Nelson, C. V. Metal detection and classification technologies. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Digest 25(1), 62–67 (2004).

Hosseini, N. & Baghelani, M. Selective real-time non-contact multi-variable water-alcohol-sugar concentration analysis during fermentation process using microwave split-ring resonator based sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 325, 112695 (2021).

Neumayer, M., George, B., Bretterklieber, T., Zangl, H. & Brasseur, G. Robust sensing of human proximity for safety applications. In 2010 IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Technology Conference Proceedings. 458–463 (IEEE, 2010).

Jiao, S., Cheng, L., Li, X., Li, P. & Ding, H. Monitoring fatigue cracks of a metal structure using an eddy current sensor. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2016, 1–14 (2016).

Sakthivel, M., George, B. & Sivaprakasam, M. A new inductive proximity sensor based guiding tool to locate metal shrapnel during surgery. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 63(12), 2940–2949 (2014).

Aqeel Mahmood Jawad, H. M. J. & Hock, G. C. Design of a beat frequency oscillator metal detector. OSR J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 56–62 (2014).

Rerkratn, A., Petchmaneelumka, W., Kongkauroptham, J., Kraisoda, K. & Kaewpoonsuk, A. Pulse induction metal detector using sample and hold method. In 2011 11th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems. 45–48 (2011).

Nyfors, E. Industrial microwave sensors-a review. Subsurf. Sens. Technol. Appl. 1(1), 23–43 (2000).

Amin, M., Sehrai, D. A., Siddiqui, O., Ramzan, R., Ehsan, A. & Abutarboush, H. A highly sensitive biosensing method using differential detection of fano resonance lineshape. J. Lightwave Technol. (2024).

Abou-Khousa, M. A., Rahman, M. S. U., Donnell, K. M. & Al Qaseer, M. T. Detection of surface cracks in metals using microwave and millimeter-wave nondestructive testing techniques-a review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–18 (2023).

Ahmed, W. W. et al. Machine learning assisted plasmonic metascreen for enhanced broadband absorption in ultra-thin silicon films. Light Sci. Appl. 14(1), 42 (2025).

Hu, B., Ren, Z., Boybay, M. S. & Ramahi, O. M. Waveguide probe loaded with split-ring resonators for crack detection in metallic surfaces. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 62(4), 871–878 (2014).

Heinz, E. et al. Passive 350 GHz video imaging systems for security applications. J. Infrared Millimeter Terahertz Waves 36, 879–895 (2015).

Hosseini, N., Olokede, S. S. & Daneshmand, M. A novel miniaturized asymmetric cpw split ring resonator with extended field distribution pattern for sensing applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 304, 111769 (2020).

Hosseini, N., Baghelani, M. & Daneshmand, M. Selective volume fraction sensing using resonant-based microwave sensor and its harmonics. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 68(9), 3958–3968 (2020).

Bilotti, F., Toscano, A. & Vegni, L. Design of spiral and multiple split-ring resonators for the realization of miniaturized metamaterial samples. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 55(8), 2258–2267 (2007).

Jarauta, E. & Falcone, F. Stripline multilayer devices based on complementary split ring resonators. Micromachines 13(8), 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13081190 (2022).

Lee, F. & Chen, M. Waveguide probe loaded with split-ring resonators for crack detection in metallic surfaces. IEEE J. Mag. 1–10 (2024).

Davis, P. & Zhang, L. Detection of surface cracks in metallic materials using an enhanced symmetrical split ring resonator. In IEEE Conference Publication. 60–70 (2024).

Siddiqui, O. et al. An ultra-sensitive Lorentz microwave sensor for detection of low-permittivity gaseous water states and sub-wavelength biosamples. IEEE Sens. J. 21(22), 26014–26022 (2021).

White, K. & Grey, L. Sensitivity enhancement of microwave split-ring-resonator sensors. IEEE J. Mag. 120–130 (2024).

Siddiqui, O. Metal detector based on Lorentz dispersion. IEEE Sens. J. 21(3), 3784–3790 (2020).

Bruschini, C., Gros, B., Guerne, F., Pièce, P.-Y. & Carmona, O. Ground penetrating radar and imaging metal detector for antipersonnel mine detection. J. Appl. Geophys. 40(1–3), 59–71 (1998).

Siddiqui, O. F., Ramzan, R., Amin, M., Omar, M. & Bastaki, N. Lorentz reflect-phase detector for moisture and dielectric sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 18(22), 9236–9242 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Cnn-based similar microwave reflection signals for improved detectability and intelligent characterization of internal defects in composite materials. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 44(1), 28 (2025).

Wilson, J. & Li, K. Array waveguide probe loaded with split-ring resonators for sizing the cracks in metal surface. IEEE J. Mag. 50–58 (2024).

Ramzan, R. et al. Electromagnetically induced absorption in the near-field of microwave radiative elements with application to foliage moisture sensing. IEEE Access 6, 77859–77868 (2018).

Baǧcı, H. A dynamically reconfigurable fano metamaterial through graphene tuning for switching and sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 3(1), 2105 (2013).

Siddiqui, O., Ramzan, R., Amin, M. & Ramahi, O. M. A non-invasive phase sensor for permittivity and moisture estimation based on anomalous dispersion. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 28626 (2016).

Mohan, A. & Kumar, N. Implantable antennas for biomedical applications: A systematic review. BioMed. Eng. Online 23, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-024-01277-1 (2024).

Baghelani, M., Abbasi, Z., Daneshmand, M. & Light, P. E. Non-invasive continuous-time glucose monitoring system using a chipless printable sensor based on split ring microwave resonators. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69547-1 (2020).

Scheers, B. Ultra-wideband ground penetrating radar with application to the detection of anti personnel landmines (Royal Military Academy, 2001).

Abou-Khousa, M. A., Rahman, M. S. U., Donnell, K. M. & Qaseer, M. T. A. Detection of surface cracks in metals using microwave and millimeter-wave nondestructive testing techniques—A review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–18 (2023).

Rahman, M. S. U., Mustapha, A. A. & Abou-Khousa, M. A. Detection of cracks under cover and corrosion using uhf probe. In 2022 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC). 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Haryono, A., Aljaberi, K., Rahman, M. S. U. & Abou-Khousa, M. A. High resolution and polarization independent microwave near-field imaging using planar resonator probes. IEEE Access 8, 191421–191432 (2020).

Salim, A., Naqvi, A. H., Pham, A. D. & Lim, S. Complementary split-ring resonator (CSRR)-loaded sensor array to detect multiple cracks: Shapes, sizes, and positions on metallic surface. IEEE Access 8, 151804–151816 (2020).

Shaterian, Z., Horestani, A. K., Martín, F. & Mrozowski, M. Design of novel highly sensitive sensors for crack detection in metal surfaces: Theoretical foundation and experimental validation. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 18540 (2023).

Wang, B., Hou, R., Wang, K., Cao, S., Yuan, C. & Feng, M. Passive rfid sensor design and research for metal crack width detection. Results Eng. 105637 (2025).

Kotriwar, Y. D., Haq, M. & Deng, Y. A novel chipless hybrid rfid sensor for metal crack detection. Appl. Sci. 15(5), 2303 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Research and Development Center at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University for facilitating the measurement setup and tools for this project.

Funding

This research is partially funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA) – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia grant number (12979-iau-2023-TAU-R-3-1-EI-).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A., T.A., and O.S. conceived the idea, S. A., M.A., and O.S. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript, S. A., M.A. performed simulations, fabrication and measurements. T.A. supervised the whole research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almoneef, T., Amir, S., Amin, M. et al. See through metallic sensor implemented using proximity resonant coupling. Sci Rep 15, 45365 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28295-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28295-w