Abstract

Living with diabetes over an extended period impacts not only physical health but also the psychosocial well-being of patients. Diabetes distress is a widespread concern affecting individuals with diabetes mellitus across all age groups, cultures, and populations. Given its significance in effective disease management, identifying modifiable factors that contribute to diabetes distress is essential for developing targeted interventions. This study was therefore undertaken to examine the prevalence and associated determinants of diabetes distress among patients receiving care at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital in northwest Ethiopia. An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from August to September 2021. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to select 376 diabetes patients. A structured, pretested, interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The data was entered in Epi Info version 7, analyzed using SPSS version 21, and presented using frequencies, percentages, tables, and graphs. Bivariable and multivariable analyses were investigated using a binary logistic regression model. Finally, variables with a P value < 0.05 were declared statistically significant. A total of 364 diabetes patients participated in the current study, making a response rate of 96.8%. Of the 364 participants, 45.6% (95% CI (40.1–50.8%)) of them had moderate to high levels of diabetes distress. Having type 1 DM [AOR = 3.03, 95% CI (1.71, 5.37)], rural residency [AOR = 2.73, 95% CI (1.55, 4.79)], insulin injection only [AOR = 2.38, 95% CI (1.73, 4.39)], and poor family support [AOR = 2.76, 95% CI (1.73, 4.39)] were associated with increased odds of diabetes distress. The prevalence of diabetes distress among diabetes patients was high. Having type 1 DM, rural residency, using insulin injection only, and having poor family support were significantly associated with diabetes distress. It is better to combine the assessment for diabetes distress as part of regular actions for diabetes care and give attention to modifiable factors like family support. To improve outcomes, healthcare policies should prioritize integrating psychosocial support into diabetes management programs, especially in rural settings, and train providers to routinely screen for diabetes distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing rapidly, making it a challenging chronic condition for both patients and caregivers1. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the number of people living with DM is projected to rise by approximately 54.7% by 2040 compared to 20152. This growing burden brings numerous challenges, including adapting to a new diagnosis, diabetes distress (DD) that undermines self-management, psychological insulin resistance (reluctance to initiate insulin therapy), and fear of hypoglycemia3.

Living with DM over time affects not only physical health but also psychosocial well-being. Complications such as microvascular (e.g., retinopathy, nephropathy) and macrovascular (e.g., heart attack, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease) are linked to increased DD and can trigger significant emotional strain, especially when compounded by negative life events4. The long-term nature of the disease, risk of complications, and social burden contribute to emotional distress and reduced quality of life5.

Diabetes distress refers to the emotional turmoil, such as intense anxiety, shame, or sadness, that arises when individuals feel overwhelmed by the daily demands of managing diabetes6. It reflects the emotional burden and negative reactions associated with self-management, including feelings of hopelessness and psychological strain caused by constant monitoring, treatment routines, and persistent fears about complications7. Diabetes distress encompasses four interrelated domains: emotional burden, regimen-related distress, stress from social relationships, and strain in patient-provider interactions8. It has been associated with increased glycated hemoglobin levels, elevated diastolic blood pressure, and higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels9,10.

Patients with diabetes are at heightened risk of psychological stress due to lifestyle changes, physical limitations, and vision problems11. Nearly one-third of individuals with diabetes experience psychological and social challenges that interfere with effective self-management12. Those with high levels of DD have been found to have a 1.8 times higher mortality rate, a 1.7 times increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and a significantly reduced quality of life13,14. It also impairs problem-solving skills essential for diabetes self-care, often resulting in poor glycemic control, increased morbidity and mortality, and higher healthcare costs15.

Diabetes distress is a global issue affecting individuals of all ages and has been documented across diverse populations and cultures16. In the United States, 15–20% of patients with diabetes experience clinically significant DD17. Globally, DD prevalence among adults ranges from 18.0 to 76.2%17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, with African studies reporting rates between 44.0 and 51.9%32,33, and Ethiopia showing a prevalence of 36.8%34. Risk factors include age19,24,25,32,33, sex19,21,33, occupation17,25,33, educational level22,28,34, duration of DM19,21,24,25,27,32, diabetic complications21,22,25,34, type of treatment25,27,32, comorbidity17,21,22,28, type of DM32, and family/social support34.

Psychological and social assessments, including screening for DD, are recommended by the American Diabetes Association as part of comprehensive diabetes care35. Despite this, psychosocial support remains underutilized in many settings. In Ethiopia, more than one-third of adults with diabetes experience DD, which exacerbates complications, impairs adherence, and worsens outcomes. Yet emotional support is often overlooked. This study was therefore conducted to assess the prevalence and associated factors of diabetes distress among patients attending the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital in northwest Ethiopia, with the goal of informing culturally appropriate interventions and improving health outcomes.

Methods and materials

Study design and period

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted from August 1 to September 30, 2021.

Populations

All diabetes patients who attend the diabetic follow-up clinic of the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital were considered as source populations of the study. Those diabetes patients who attended the diabetic follow-up clinic during the study period were study populations.

Eligibility criteria

All diabetes patients aged 18 years and older who attended the follow-up clinic at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital during the study period were eligible for inclusion. However, patients were excluded if they were severely ill, unable to communicate effectively, or had a previously diagnosed psychiatric condition.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula by considering the following assumptions: proportion of diabetes distress 36.8%34, 95% confidence interval, and a 5% margin of error. The final sample size was 376 after adding a 5% non-response rate. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to select study participants. The total estimated population during the two-month data collection period was 1600, based on records from the chronic disease follow-up clinic. To determine the sampling interval, the value of k was calculated as k = 1600/376 ≈ 4. This means every 4th individual was selected from the population list. To ensure randomness, the first participant was selected using a random starting point between 1 and 4. From that starting point, every 4th individual was included in the sample until the required sample size of 376 was reached. This approach maintained both systematic structure and randomization, reducing selection bias and enhancing representativeness.

Variables of the study

Dependent variable Diabetes distress.

Independent variables socio-demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, educational status, occupation, and residence); clinical factors (type of DM, duration of DM, family history of DM, comorbidity, diabetic complications, and type of treatment); personal factor (family support).

Operational definitions

Diabetes distress A form of emotional distress, which is specific to diabetes and reflects the emotional reactions of all aspects of diabetes and diabetes care. It was categorized as < 2.0 = no distress and ≥ 2.0 = distress. Among those with distress, scores between 2.0 and 2.9 were classified as moderate distress, and scores of 3.0 or higher were categorized as high distress36.

Comorbidity A diabetic patient who had a known additional disease other than DM was considered as having comorbidity37.

Diabetic complications A diabetic patient who had one of the following (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, myocardial infarction, and stroke) was considered to have diabetes complications38.

Family support participants who scored at or above the mean of the family APGAR score were considered to have good family support, while those who scored below the mean were categorized as having poor family support.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data was collected using a structured, pre-tested, interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire contains 38 questions arranged in four parts: Part I: seven socio-demographic questions; Part II: nine clinically related questions; Part III: seventeen questions to assess diabetes distress; and Part IV: five questions to assess family support. Diabetes distress was measured by using the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS)36. This scale contains 17 items that use the Likert scale. Items associated with distress experienced over the past month were scored from 1 (not a problem) to 6 (a very serious problem). It measures emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress, and interpersonal distress. Each item was rated considering the degree to which each of the 17 items may have distressed or bothered the diabetic patients during the past month. The total possible scores for DDS-17 were 17–102 (average 1–6), and it was calculated by summing the 17 items’ results and dividing them by 17. The DDS has been validated, and its Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory (0.93)36. Family support was measured using the Family APGAR (adaptation, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve) scale, which consists of 5 items scored from 0 (hardly ever) to 2 (almost always)39. The total score range is from 0 to 10. The larger the score, the greater the amount of satisfaction with family functioning. The Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale was 0.8640.

Data processing and analysis

Following data collection, each questionnaire was reviewed for completeness and consistency, and possible corrections were done by investigators. Data was entered into Epi-info version 7 and transferred into SPSS version 21, and then data cleaning and coding were done to make it ready for analysis. The results of the descriptive statistics were expressed as mean, standard deviation, percentage, and frequency using tables and graphs. Binary logistic regression was employed to identify factors associated with diabetes distress. Those variables with a p-value less than or equal to 0.2 from the bivariable analysis were candidates for multivariable analysis. The multivariable analysis was used to control for potential confounders, and a p value of < 0.05 was used to declare the significance of the association. Moreover, the strength of the association between different independent variables with the dependent variable was measured using odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval. Multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and a variable is considered to be multi-collinear if its VIF score is 10 or more. However, in this investigation, all variables had VIF values ranging from 1 to 10.

Data quality management

The data collection instrument was prepared in English and translated into the local language, Amharic, and back-translated to English by language experts to check for consistency. A pretest was done on 5% of the total sample size at Debre Tabor Referral Hospital. Necessary modifications were made upon the identification of ambiguity in the questionnaire. We recruited, trained, and assigned three diploma nurses and one MSc nurse for data collection and supervision, respectively. The one-day training was given to both the data collectors and supervisor about the objective of the study, the technique of data collection, the content of the questionnaire, and the issue of confidentiality of the participants.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

A total of 364 diabetic patients participated in the current study, making a response rate of 96.8%. The mean age of the participants was 49.7 ± 16.0 (SD) years, and 30.8% of them fell in the range of 50–64 years. More than half (50.8%) of the respondents were male, and 59.7% of them were married. Regarding the educational status, 24.5% of the participants couldn’t read and write, and 34.3% of them completed primary education. More than two-thirds (67.1%) of diabetic patients were Orthodox in terms of religion, and only 8.0% of them were students. Concerning their place of residence, more than three-fourths (78.6%) of the respondents were urban dwellers (Table 1).

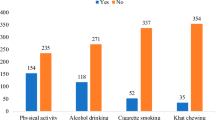

Clinical and personal-related characteristics of the participants

Of the total participants, about 42.3% of them were not sure of the type of DM they had. More than half (55.5%) of the participants lived with DM for five years and below. About 22.5%, 18.4%, and 13.5% of the respondents had a family history of DM, comorbidities, and diabetic complications, respectively. More than three-fourths (76.1%) and 38.8% of diabetic patients had hypertension and nephropathy, respectively. Regarding the type of treatment, 46.4% of the respondents used injections only. More than half (58.2%) of the participants had poor family support (Table 2).

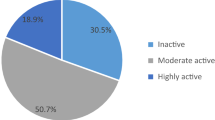

Prevalence of diabetes distress

The mean ± SD of total diabetes distress was 2.07 ± 0.84. The mean score for each domain of DD, such as emotional burden, interpersonal distress, physician-related distress, and regimen-related distress, was (2.47 ± 1.06), (1.94 ± 1.01), (1.67 ± 0.79), and (2.80 ± 1.0), respectively (Fig. 1). The overall prevalence of diabetes distress was 45.6% [95% CI (40.1%, 50.8%)] (Fig. 2), of which 33.2% (2–2.9) and 12.4% (≥ 3) of them had moderate and high-level distress, respectively.

Factors associated with diabetes distress

Using bivariable analysis, factors like age of patients, residence, type of DM, family history, diabetic complication, type of treatment, and family support were eligible for multivariable analysis. In the final model, residence, type of DM, type of treatment, and family support were statistically significant factors associated with DD. Accordingly, patients with type one DM were three times more likely to have DD compared with those patients who didn’t know the type of DM they had [AOR = 3.03, 95% CI (1.71, 5.37)]. The odds of having DD were 2.7 times higher among diabetes patients who came from rural areas than patients who came from urban areas [AOR = 2.73, 95% CI (1.55, 4.79)]. Moreover, diabetes patients who used insulin injection only were 2.38 times more likely to have DD compared with patients who used pills only [AOR = 2.38, 95% CI (1.35, 4.18)]. Similarly, the odds of having DD were nearly three times higher among patients who had poor family support than their counterparts [AOR = 2.76, 95% CI (1.73, 4.39)] (Table 3).

Discussion

Diabetes distress involves negative emotional responses to all features of diabetes and diabetes care, including DM diagnosis, risk of complications, self-management difficulties, management, or uncooperative social structures surrounding the disease41. Although it has recently been demonstrated that self-monitoring is common among diabetes patients in low-resource nations, diabetes-related distress has a negative impact on self-care and glucose control42,43. The current study was intended to assess the prevalence and associated factors of DD among diabetes patients in northwest Ethiopia. In the present study, 45.6% of the patients had DD. This finding was relatively consistent with studies conducted in South Africa (44%)33, Malaysia (49.2%)17, Tehran, Iran (48.6%)21, China (42.1%)31, and Bangladesh (48.5%)25. However, the current finding was higher than studies conducted in southwest Ethiopia (36.8%)34, Singapore (21%)30, Saudi Arabia (22.3% and 25%)18,19, Haryana, India (18.0%)22, Greece (24.4%)26, Jilin province of China (26.8%)28, and Chi Minh City, Vietnam (29.4%)24. The possible justification for the higher prevalence of DD in the current study than in the study conducted in southwest Ethiopia might be due to differences in the study participants. The previous study was conducted among patients with type 2 DM only, whereas the current study incorporated patients with both type 1 and 2 DM. The higher prevalence in the current study than in other previous studies might also be due to the deprived quality of diabetes care provision, lower educational status, differences in the instruments used to measure the level of DD, and other forms of threats associated with living with diabetes. On the other hand, this finding was lower than studies conducted in southeast Nigeria (51.9%)32, Pakistan (76.2%)20, Iran (63.7%)27, south India (77.5%)23, and Canada (52.5%)29. The difference might be due to differences in study participants (most studies conducted among patients with type 2 DM), sampling technique (most studies used convenience sampling), and sample size (the Canadian study was conducted among only 41 individuals). The discrepancy might also be due to patients in the current study who might have underrated their level of distress and disparity in associated conditions in addition to DM among patients.

In the present study, having type 1 DM increases the risk of developing diabetes distress compared to those who didn’t know the type of DM they had. Similar findings were reported by studies conducted in southeast Nigeria and Vietnam32,44. This could be attributed to type 1 DM being common in the younger age group (they may have fewer handling mechanisms), being treated by insulin (price of medications and a more demanding treatment), and living with diabetes for a long period (they might face numerous emotional and physical stressors). The “not sure (patients who didn’t know the type of DM they had)” group included individuals who could not identify whether they had type 1 or type 2 DM, which may reflect limited health literacy, poor communication with healthcare providers, or gaps in diabetes education. This uncertainty can complicate analysis, as it introduces heterogeneity into the comparison group; some of these patients may have type 1 or type 2 DM but lack clarity about their diagnosis. Their lower reported distress may stem from reduced engagement in self-management or limited awareness of disease burden, rather than true emotional well-being. As such, interpreting results involving this group requires caution, since their distress levels may be underestimated due to informational gaps rather than actual clinical differences.

Similarly, rural dwellers were at a higher risk of DD in the present study. A study conducted in eastern Sudan reported a similar finding45. This might be due to rural–urban health disparities in Ethiopia because rural dwellers had limited access to health services, traveled long distances to access health services, and had lower education levels and more poverty compared with urban dwellers, which affected their self-management ability of diabetes and related comorbidities46. Early detection and intervention are hampered by inadequate rehabilitative services, a lack of qualified experts, and restricted access to basic care. Socioeconomic disadvantages and environmental factors that are common in rural areas exacerbate these difficulties. Targeted health system strengthening is needed to address these gaps, including workforce development, integrated care models, and investments in rural health infrastructure.

In addition, diabetes patients who used insulin injections only were at a higher risk of developing DD. This finding was supported by studies conducted in southeast Nigeria, Iran, and Vietnam27,32,44. This is because commencement of insulin therapy can make the patient recognize that his/her disease is becoming worse; therefore, this may lead to extreme anxiety, embarrassment, sadness, or rejection due to a perceived incapability to cope with the necessities of insulin therapy47,48. From an analytical perspective, this finding highlights the importance of considering treatment modality as a predictor of DD. It also suggests that patients on insulin may benefit from targeted psychosocial support and counseling to help manage the emotional challenges of their treatment regimen. Identifying and addressing distress in this group could improve both mental well-being and diabetes outcomes. While our study found that patients using insulin injections only were at higher risk of DD, it is important to consider the possibility of reverse causality, where distress itself may lead to poor adherence, resulting in worse glycemic control and ultimately necessitating insulin therapy. In this scenario, emotional distress could precede and contribute to treatment intensification, rather than being caused by insulin use alone. Patients experiencing high levels of distress may struggle with self-management, which can deteriorate their clinical outcomes and prompt a shift to insulin-based regimens. Therefore, interpreting the association between insulin use and DD requires caution, as the observed relationship may reflect a complex interplay of psychological and clinical factors rather than a direct causal link.

The other factor associated with DD was family support, in which diabetes patients with poor family support had higher odds of developing distress. A study conducted in southwest Ethiopia, Norway, and Thailand supported this finding4,34,49. This is because when family members behave negatively, e.g., by irritating or criticizing specific health-related activities, individuals with diabetes may react by taking in higher levels of DD. Peer support was also effective in reducing diabetes-related distress50. This demonstrates how important family dynamics are in Ethiopian culture. Families have a crucial role in Ethiopian health decision-making, caring, and emotional fortitude. Patients may feel alone, have more emotional burden, and have trouble managing themselves when this assistance is lacking. Cultural customs like sharing meals might make it more difficult to follow a diet, particularly if family members are unaware of how to treat diabetes. Family-based diabetes self-management education and support programs have been found to dramatically increase supportive behaviors and decrease distress, according to studies conducted in Western Ethiopia51. These findings highlight the necessity of culturally sensitive interventions that actively involve families in diabetes care, foster empathy, and dispel myths in order to lessen suffering and enhance results.

To integrate DD screening into routine care in Ethiopia, health facilities should include the DDS-17 during regular follow-up visits, with trained nurses or health officers administering it. Results should be recorded and linked to referral options like counseling or peer support. Using task-shifting and existing clinic workflows makes this approach practical and scalable.

Strengths and limitations of the study

One of the key strengths of this study is its contextual relevance. Conducted in a setting where the psychological impact of chronic illnesses is underexplored, it fills a critical local knowledge gap while contributing valuable insights to the global literature. The focus on modifiable social factors, such as family support, also highlights opportunities for community-based interventions to reduce emotional distress and improve patient well-being.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, since the study was facility-based, it may not fully capture the experiences of diabetes patients in the broader community, particularly those who rarely seek medical care. Second, reliance on self-reported data introduces potential recall bias, which may affect the accuracy of responses. Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference between diabetes distress and associated factors. Fourth, the study lacked clinical validation of self-reported diagnoses, including diabetes complications, which may reduce diagnostic precision. Additionally, a high proportion of participants were uncertain about their type of diabetes, which limits the interpretability of related findings. Finally, the use of interviewer-administered questionnaires may have introduced social desirability bias, potentially influencing how participants reported emotional distress and other sensitive information.

Conclusion

The study found a high prevalence of DD, with significant associations observed among patients with type 1 DM, rural residency, insulin-only treatment, and poor family support. These findings highlight the need to integrate DD screening into routine diabetes care using a holistic management framework. Special attention should be given to high-risk groups and modifiable factors like family support. Enhancing clinical awareness and providing regular health education on diabetes and its psychological impact can improve patient outcomes. From a policy perspective, prioritizing emotional well-being in chronic disease care and training healthcare providers to recognize and address DD are essential steps toward more responsive and inclusive health systems. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to clarify causal pathways and intervention trials to evaluate strategies for reducing diabetes distress, especially among high-risk and underserved populations.

Data availability

All data is available upon request. The reader could contact the corresponding author for the underlying data.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DD:

-

Diabetes distress

- DDS:

-

Diabetes distress scale

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- IDF:

-

International diabetes federation

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical product and service solutions

References

Snoek, F. J. et al. Monitoring of individual needs in diabetes (MIND): baseline data from the cross-national diabetes attitudes, wishes, and needs (DAWN) MIND study. Diabetes Care 34(3), 601–603 (2011).

Atlas, D. International diabetes federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation (2015).

Fisher, L., Glasgow, R. E. & Strycker, L. A. The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 33(5), 1034–1036 (2010).

Karlsen, B., Oftedal, B. & Bru, E. The relationship between clinical indicators, coping styles, perceived support and diabetes-related distress among adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Adv. Nurs. 68(2), 391–401 (2012).

Rane, K., Wajngot, A., Wändell, P. & Gåfvels, C. Psychosocial problems in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes: Number and characteristics. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 93(3), 371–378 (2011).

Kalra, S., Verma, K. & YP, S. B. Management of diabetes distress. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 67(10), 1625–1627 (2017).

Hagger, V., Hendrieckx, C., Sturt, J., Skinner, T. C. & Speight, J. Diabetes distress among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Curr. Diab.Rep. 16(1), 9 (2016).

Winchester, R. J., Williams, J. S., Wolfman, T. E. & Egede, L. E. Depressive symptoms, serious psychological distress, diabetes distress and cardiovascular risk factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 30(2), 312–317 (2016).

Strandberg, R. B., Graue, M., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Peyrot, M. & Rokne, B. Relationships of diabetes-specific emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and overall well-being with HbA1c in adult persons with type 1 diabetes. J. Psychosom. Res. 77(3), 174–179 (2014).

Strandberg, R. B. et al. Longitudinal relationship between diabetes-specific emotional distress and follow-up HbA1c in adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Med. 32(10), 1304–1310 (2015).

Rehman, A. & Kazmi, S. Prevalence and level of depression, anxiety and stress among patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Pak. Inst. Med. Sci. 11(2), 81–86 (2015).

Grigsby, A. B., Anderson, R. J., Freedland, K. E., Clouse, R. E. & Lustman, P. J. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 53(6), 1053–1060 (2002).

Carper, M. M. et al. The differential associations of depression and diabetes distress with quality of life domains in type 2 diabetes. J. Behav. Med. 37(3), 501–510 (2014).

Dalsgaard, E.-M. et al. Psychological distress, cardiovascular complications and mortality among people with screen-detected type 2 diabetes: Follow-up of the ADDITION-Denmark trial. Diabetologia 57(4), 710–717 (2014).

Egede, L. E., Walker, R. J., Bishu, K. & Dismuke, C. E. Trends in costs of depression in adults with diabetes in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2004–2011. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 31(6), 615–622 (2016).

Nicolucci, A. et al. Educational and psychological issues diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN2TM): Cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabetic Med. 30, 767–777 (2013).

Chew, B.-H., Vos, R., Mohd-Sidik, S. & Rutten, G. E. Diabetes-related distress, depression and distress-depression among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 11(3), e0152095 (2016).

Aljuaid, M. O., Almutairi, A. M., Assiri, M. A., Almalki, D. M. & Alswat, K. Diabetes-related distress assessment among type 2 diabetes patients. J. Diabetic Res. 2018(1), 7328128 (2018).

Alzughbi, T. et al. Diabetes-related distress and depression in Saudis with type 2 diabetes. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 453 (2020).

Arif, M. A. et al. The ADRIFT study–Assessing diabetes distress and its associated factors in the Pakistani population. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 68(11), 1590–1596 (2018).

Azadbakht, M., Tanjani, P. T., Fadayevatan, R., Froughan, M. & Zanjari, N. The prevalence and predictors of diabetes distress in elderly with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 163, 108133 (2020).

Gahlan, D., Rajput, R., Gehlawat, P. & Gupta, R. Prevalence and determinants of diabetes distress in patients of diabetes mellitus in a tertiary care centre. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 12(3), 333–336 (2018).

Hemavathi, P., Satyavani, K., Smina, T. & Vijay, V. Assessment of diabetes related distress among subjects with type 2 diabetes in South India. Int. J. Psychol. Counsel. 11(1), 1–5 (2019).

Huynh, G. et al. Diabetes-related distress among people with type 2 diabetes in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: prevalence and associated factors. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Therapy 14, 683 (2021).

Islam, M., Karim, M., Habib, S. & Yesmin, K. Diabetes distress among type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Med. Biomed. Res. 2(2), 113–124 (2013).

Kintzoglanakis, K., Vonta, P. & Copanitsanou, P. Diabetes-related distress and associated characteristics in patients with type 2 diabetes in an urban primary care setting in Greece. Chronic Stress 4, 2470547020961538 (2020).

Parsa, S., Aghamohammadi, M. & Abazari, M. Diabetes distress and its clinical determinants in patients with type II diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 13(2), 1275–1279 (2019).

Qiu, S. et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among diabetes mellitus adults in the Jilin province in China: A cross-sectional study. PeerJ 5, e2869 (2017).

Sidhu, R. & Tang, T. S. Diabetes distress and depression in South Asian Canadians with type 2 diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 41(1), 69–72 (2017).

Tan, M. L. et al. Factors associated with diabetes-related distress over time among patients with T2DM in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. BMC Endocr. Disord. 17(1), 1–6 (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. Diabetes-related distress and its associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China. Psychiatry Res. 252, 45–50 (2017).

Onyenekwe, B. M., Young, E. E., Nwatu, C. B., Okafor, C. I. & Ugwueze, C. V. Diabetes distress and associated factors in patients with diabetes mellitus in south east Nigeria. Dubai Diabetes Endocrinol. J. 26(1), 31–37 (2020).

Ramkisson, S., Pillay, B. J. & Sartorius, B. Diabetes distress and related factors in South African adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Endocrinol. Metab. Diabetes S. Afr. 21(2), 35–39 (2016).

Geleta, B. A. et al. Prevalence of diabetes related distress and associated factors among type 2 diabetes patients attending hospitals, southwest Ethiopia, 2020: A cross-sectional study. Patient Related Outcome Meas. 12, 13 (2021).

Haas, L. et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 38(5), 619–629 (2012).

Polonsky, W. H. et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care 28(3), 626–631 (2005).

Feinstein, A. The pre-therapeutic classification of comorbidity in chronic disease. J. Chron. Dis. 23, 455–468 (1970).

Forbes, J. M. & Cooper, M. E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 93(1), 137–188 (2013).

Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C. & Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 15(2), 303–311 (1982).

Neabel, B., Fothergill-Bourbonnais, F. & Dunning, J. Family assessment tools: A review of the literature from 1978–1997. Heart Lung 29(3), 196–209 (2000).

Stanković, Z.J.-G.M. & Lecić-Tosevski, D. Psychological problems in patients with type 2 diabetes—clinical considerations. Vojnosanit Pregl. 70(12), 1138–1144 (2013).

Bhaskara, G. et al. Factors associated with diabetes-related distress in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets and Therapy 1, 2077–2085 (2022).

Mohamed, S. et al. Knowledge and practice of glucose Self-Monitoring devices among patients with diabetes. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 18(2), 127–138 (2023).

Nguyen, V. B. et al. Diabetes-related distress and its associated factors among patients with diabetes in Vietnam. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 1181–1189 (2020).

Omar, S. M., Musa, I. R., Idrees, M. B. & Adam, I. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in eastern Sudan. BMC Psychiatry 21(1), 1–8 (2021).

Rasmussen, B. et al. Self-management of diabetes and associated comorbidities in rural and remote communities: A scoping review. Aust. J. Primary Health 27(4), 243–254 (2021).

Wallia, A. & Molitch, M. E. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 311(22), 2315–2325 (2014).

Kalra, S. B. Y. Insulin distress. US Endocrinol. 14(1), 27 (2018).

Tunsuchart, K., Lerttrakarnnon, P., Srithanaviboonchai, K., Likhitsathian, S. & Skulphan, S. Type 2 diabetes mellitus related distress in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(7), 2329 (2020).

Ju, C. et al. Effect of peer support on diabetes distress: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabetic Med. 35(6), 770–775 (2018).

Diriba, D. C., Leung, D. Y. & Suen, L. K. Effects of family-based diabetes self-management education and support programme on support behaviour amongst adults with type 2 diabetes in Western Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20867 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the University of Gondar, data collectors, and study participants.

Funding

No funding has been received for the conduct of this study and/or the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content were conducted by E.G.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before conducting the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of the School of Nursing on behalf of the University of Gondar. A letter of permission was obtained from the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital director. After the purpose and objective of the study had been explained, written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. All participants were also informed that participation was voluntary and they could withdraw from the study at any time if they were not comfortable with the questionnaire. To keep the confidentiality of any information provided by study subjects, the data collection procedure was kept anonymous. The study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mekonen, E.G. Prevalence and factors associated with diabetes distress in northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 44547 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28320-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28320-y