Abstract

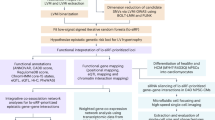

Heart failure (HF) represents the final stage of multiple cardiovascular diseases. Cuproptosis may play an important role in the progression of HF. This study aimed to identify cuproptosis-related biomarkers in HF and elucidate their potential regulatory mechanisms. We downloaded the HF-related bulk dataset from the GEO database for performing WGCNA and differential analysis. A total of 5,563 HF-related co-expressed genes were identified. By intersecting the above genes with cuproptosis-associated genes, we identified three candidates (DBT, Atox1 and DLD) that are potentially involved in cardiac hypertrophy in HF. Among them, DBT and DLD were lowly expressed whereas Atox1 was highly expressed in the disease group. We selected Atox1 for subsequent analysis. Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) method was applied for establishing a mouse model of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy. In the model mice, we found significantly overexpressed Atox1 (fold change = 3.47) by qRT-PCR and increased levels of cuproptosis marker proteins SLC31A1 and FDX1 as well as Dlat aggregation. To further examine the action mechanism of Atox1, cardiomyocytes (H9c2) were treated with Ang II to simulate cardiac hypertrophy in vitro, followed by ATOX1 knockdown. It was found that low expression of Atox1 inhibited cuproptosis and suppressed cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. When cuproptosis was activated in Ang II + si-Atox1 group using elesclomol + CuCl2, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was enhanced, while Atox1 expression remained unchanged. In summary, Atox1 plays a significant role in HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy and can regulate cuproptosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is associated with high rates of morbidity, hospital readmission, and mortality1, representing a major global public health challenge. It is a clinical syndrome of terminal cardiac decompensation in various cardiovascular diseases. As is known, HF arises from functional or structural abnormalities of the heart that compromise its ability to fill and eject blood effectively, leading to cardiac output inadequate to meet the metabolic demands of the body tissues2. The occurrence of HF is primarily driven by the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes as an adaptive response to biomechanical stress, including hemodynamic overload and elevated level of neurohormone mediators, which ultimately leads to sustained pathological cardiac hypertrophy3. Currently, the treatment of HF primarily relies on pharmacological therapies-including ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and SGLT2 antagonists-as well as surgical interventions such as aortic valve replacement and left ventricular assist device therapy4,5. Despite these advances, there are still high mortality rates among HF patients, underscoring the urgent need to identify effective therapeutic targets and interventions to improve patients’ cardiovascular function.

Copper, as an essential micronutrient, plays an indispensable role in maintaining organismal homeostasis. Dysregulation of copper metabolism has recently been shown to induce a novel form of programmed cell death termed cuproptosis, which occurs through the disruption of mitochondrial morphology and function1. Mechanistically, cuproptosis differs fundamentally from other well-characterized cell death modalities such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis at the molecular level6. Mitochondria, serving as both the central hub of cellular energy metabolism and a regulatory nexus of cell death, relies critically on their functional integrity to maintain cardiomyocyte viability. Mounting evidence indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction can directly drive the pathogenesis and progression of HF through multiple mechanisms, including disrupted energy metabolism, impaired protein quality control, and dysregulated programmed cell death pathways7,8,9. Notably, treatment with copper chelator has been shown to enhance cardiac function, restore mitochondrial function, and partially reverse copper-mediated cell death10. Moreover, Binghui Kong et al. reported that Sirtuin3 alleviates pathological myocardial remodeling caused by stress overload by inhibiting cuproptosis in cardiomyocytes11. These findings highlight cuproptosis as a key therapeutic target for HF. In this study, by performing bioinformatics analysis, Atox1 was identified as a cuproptosis-related gene potentially involved in HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy. Given that the mechanistic involvement of Atox1 in cardiovascular diseases has not been previously reported, we sought to define its role both in vivo and in vitro. Our research aimed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy in HF and provide novel therapeutic targets for the clinical treatment of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy.

Materials and methods

Dataset acquisition and processing

HF-related bulk datasets GSE101977 and GSE66630, as well as a scRNA-seq dataset GSE122930, were downloaded from the GEO database. GSE101977 contained 3 transverse aortic constriction (TAC) samples and 3 sham samples; GSE66630 contained 4 TAC samples and 4 sham samples; GSE122930 contained 1 TAC sample and 1 sham sample. Additionally, 49 cuproptosis-related genes were sorted out from the published literature for subsequent bioinformatics analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Bulk datasets GSE101977 and GSE66630 were merged and subsequently normalized using “limma” (v 3.56), and batch effects between datasets were eliminated using “SVA” (v 3.48).

Single-cell analysis

Single-cell analysis of GSE122930 was carried out with “Seurat” (v 4.3.0). Quality control criteria of the single-cell data included: 1) cells with 200-3,000 genes were retained; 2) cells with mitochondria below 5% were selected; and 3) cells with RNA count < 10,000 were included. Subsequently, cells were further annotated using the “ImmGenData” package in “celldex”, and cell-cell communication was analyzed with “cellchat”12,13.

Functional enrichment analysis

“org.Mm.eg.db” (v 3.16.0), “clusterProfiler” (v 4.6.2), and “ggplot2” (v 3.4.2) are packages respectively used for performing GO analysis and KEGG analysis14,15. Enrichment results were visualized using the “goplot” package (top 10 items shown). ssGSEA was conducted using “gseKEGG” in “clusterProfiler” (v 4.8).

Differential analysis

“compare” package in “amplicon” was used for performing differential analysis. Volcano plots were generated with the “ggplot2” package (v 1.16.0), and Pearson correlation analysis was performed in R.

WGCNA

WGCNA of the merged dataset was performed using the “WGCNA” package. After sample clustering and removal of outlier samples from the merged dataset, the correlation of gene expression in the dataset was calculated, and the subscale operation was carried out. After the soft threshold (the value of subscale) was set to 5 (R2 = 0.77), the scale-free network was generated, and the genes were constructed into an adjacency matrix with R2 = 0.77, which was subsequently transformed into a topological overlap matrix. Finally, 21 modules were determined.

Immunoinfiltration analysis

“CIBERSORTx” package was applied for performing immunoinfiltration analysis of the samples in the dataset.

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice that were eight weeks old were obtained from Hangzhou Medical College Laboratory Animal Center, and they were housed in an environment with stable temperature and humidity conditions (23 °C, 65%) with a 12/12 h light/dark regime. All experimental procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the guidelines of the National Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee. This animal study was granted approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang Center of Laboratory Animals (No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20020190).

TAC model establishment

After anesthesia with CO2, mice were securely placed in a supine position on a temperature-controlled heating pad to maintain their body temperature. After hair removal and alcohol disinfection on their neck and chest, endotracheal intubation was performed, with the respiratory rate set at 120 times/min. After observing that the respiratory rate of mice was in sync with the ventilator, the skin, pectoral muscle, and intercostal muscle were obtained from the second intercostal space of the heart, and the intercostal space was extended with a chest dilator. A small section of 6 − 0 suture thread was positioned under the arterial arch between the innominate artery and the left common carotid artery, tied as a slip knot around the arterial arch, and a 27G flat head needle was stuck into the slip knot and put parallel to the artery. The slip knot was tightened to secure the needle against the artery, followed by an additional knot. The needle was promptly removed, creating a surgical stenosis with a theoretical diameter of 0.4 mm in the aortic arch distal to the brachiocephalic artery. The thymus was repositioned, and the intercostal muscle and skin were sutured with 6 − 0 polypropylene sutures. After the procedure, the general conditions of mice were carefully examined. The tracheal cannula was pulled out, and the binding tooth bands and limb tapes were detached. Each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 ml penicillin to keep warm. If signs of dehydration were observed, normal saline was injected intraperitoneally. After regaining consciousness, the mice were returned to their housing cages. In contrast, mice in the Sham group did not undergo the open-chest surgery of aortic ligation. After 28 days of surgery, the mice were euthanized with CO2, and their hearts were collected and stored at −80 ℃ for subsequent experiments. The heart weight-to-body weight ratio was calculated by measuring both the heart and body weights.

Cell culture and model preparation

Rat cardiomyocytes H9c2 (Pricella, CL-0089) were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS in an incubator (5% CO2, 37 ℃). Cardiac hypertrophy was induced by treating H9c2 cells with Ang-II for 48 h. After being plated in 24-well plates at a density of 1.2 × 105cells/well, H9c2 cells were cultured with jetPRIME® transfection reagent (Polyplus, 101000001) and siRNA oligonucleotide of Atox1 (Sangon Biotech) for 6 h, followed by incubation in DMEM for 24 h. si-NC was constructed as a negative control. To activate cuproptosis, H9c2 cells were treated with 10 µM elesclomol and 1 µM CuCl2 for 24 h.

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized and fixed on the surgical board in a supine position, with chest hair removed to expose the left thorax and sternum. M-mode ultrasound was applied for measuring the long axis section of the left ventricle. Ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) were measured simultaneously over three cardiac cycles.

HE and masson staining

The collected mouse heart tissue was treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, followed by dehydration and paraffin embedding to prepare tissue sections. HE Staining Kit (Beyotime, C0105M) or Masson’s Trichrome Staining Kit (Beyotime, C0189S) was used to stain the tissue sections according to the experimental requirements.

DLAT oligomerization

The prepared cardiac tissue sections were antigen repaired, stained with DLAT Rabbit pAb (ABclonal, A14530), incubated with secondary antibodies, and finally photographed under a fluorescence microscope to detect Dlat accumulation in cardiac tissue or cells.

qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from mouse heart tissues and cardiomyocytes using the Trizol reagent (Beyotime, R0016). cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScriptTM VILOTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, 11754050). The quantitative PCR procedure was conducted with the BeyoFastTM SYBR Green qPCR Mix (Beyotime, D7501) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers utilized in our experiment are as follows: mmu-Atox1-F: GCGTCAGTCATGCCGAAGC; mmu-Atox1-R: GGTCAATGTTGAACTCCACTCCTC; rat-Atox1-F: TGTGGAGGCTGTGCGGAAG; rat-Atox1-R: GTTGAGAGTTGCCAGCAGGATG; mmu-ANP-F: TGGGCTTCTTCCTCGTCTTGG; mmu-ANP-R: CTCCAGGTGGTCTAGCAGGTTC; rat-ANP-F: TGAGCGAGCAGACCGATGAAG; rat-ANP-R: GCCCGAGAGCACCTCCATC; mmu-BNP-F: TTCCAAGGTGACACATATCTCAAGC; mmu-BNP-R: TCCTACAACAACTTCAGTGCGTTAC; rat-BNP-F: TGCCTGGCCCATCACTTCTG; rat-BNP-R: CATCGTGGATTGTTCTGGAGACTG; mmu-β-MHC-F: AGACAGAGGAAGACAGGAAGAACC; mmu-β-MHC-R: CACCTTGCGGAACTTGGACAG; rat-βMHC-F: GCGACGTGGGCGAGTACC; rat-βMHC-R: CCTCCGTCTCCTCGTAGTTGTG; mmu-GAPDH-F: GGCAAATTCAACGGCACAGTCAAG; mmu-GAPDH-R: TCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTGATGG; rat-GAPDH-F: ACGGCAAGTTCAACGGCACAG; rat-GAPDH-R: CGACATACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC.

ELISA

The expression of inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNF-α were measured using the Mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit (Beyotime, PT512) and Mouse IL-6 ELISA Kit (Beyotime, PI326).

Western blot (WB)

Proteins were extracted using a cell lysis buffer supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor. We quantified the protein content using the bicinchoninic acid assay. Subsequently, after electrophoresis, the proteins were electrotransferred to a membrane and incubated with the following primary antibodies: FDX1 (Abcam, ab108257) and SLC31A1 (cell signaling technology, 13086). GAPDH (Invitrogen, PA1-988) was the internal reference gene. After protein development, their expression levels were detected using ImageJ software (Version 1.54, https://imagej.net/ij/). Three biological replicates were conducted for every experiment.

F-actin staining

Cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. After blocking with a solution containing 1% PBS and 0.1% Triton-X for 5 min, cells were first incubated with a monoclonal antibody against F-actin (Abcam, ab112125) overnight at 4 ℃ and subsequently with secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter, the cells were coated with DAPI. A fluorescent microscope was used to capture images of the visible cells.

Detection of the intracellular level of Cu+ with fluorescence probes

Cells were labeled with coppersensor-1 (CS1), and the level of intracellular Cu+ was visualized under a microscope.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS® Statistics GradPack and Faculty Packs were employed for performing statistical analysis, and graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism 9. The experimental data are presented as mean (\(\:\stackrel{-}{\text{x}}\)) ± standard deviation (SD) values. All data was examined through two-sided t-tests.

Results

scRNA‑seq analysis of HF

After quality control of the scRNA‑seq dataset GSE122930, we obtained a total of 6,018 cells containing 27,998 genes. We divided all these cells into 16 clusters on the basis of the expression of individual genes in each cell (Fig. 1A–C). After cell annotation, 9 cell types were identified: B cells, Monocytes, Basophils, DCs, ILCs, Macrophages, NK cells, NKT and T cells (Fig. 1D). We then compared the proportion of each cell in the sham and TAC groups, respectively. Our results demonstrated that B cells and Monocytes accounted for a large proportion and were widely distributed in both groups (Fig. 2A). Finally, we analyzed the gene expression differences between groups within each cell, and identified 8,157 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with |log2FC| > 0.25 & P < 0.05 as the criterion (Fig. 2B). Functional enrichment analysis of these DEGs indicated that most of them were enriched in protein kinase activator activity, ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding, cytosolic small ribosomal subunit, negative regulation of cell-cell adhesion, modulation of T cell activation and MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 2C, D).

Source https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Gene differences between groups in each cell. (A) Proportion of each cell in each group; (B) Gene expression differences in individual cells; (C) GO analysis of DEGs; (D) KEGG analysis of DEGs (KEGG, reproduced with permission from Kanehisa Laboratories.

Cell–cell communication among cell types during HF

To clarify the effect of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy on myocardial intercellular signaling, cell-cell communication analysis was conducted in the sham and TAC groups, respectively. Both the number and intensity of intercellular communication were markedly higher in the TAC versus the sham group (Fig. 3A–C). We then compared the overall information flow between the two groups, and ranked the key signaling pathways. The analysis demonstrated that the FLT3, IGF, GALECTIN and CCL signaling pathways were more important in the TAC group, whereas the CSF, IL4 and PARs signaling pathways were more important in the sham group (Fig. 3D). Next, the communication intensity of each cell type, as input/output signal in different groups, was visualized using a two-dimensional planar graph. The results indicated that Macrophages exhibited markedly elevated communication intensity in the TAC relative to the sham group (Fig. 3E). Moreover, the CCL signaling pathway showed the most notable differences when Macrophages acted as input/output signal (Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that targeting the CCL pathway, which regulates the interaction of Macrophages with other cells, may offer a potential therapeutic approach to attenuate or delay the development of HF.

Cell–cell communication among cell types during HF. (A) Network diagram illustrating the intensity and number of cell communication in the sham group; (B) Network diagram illustrating the intensity and number of cell communication in the TAC group; (C) Bar chart comparing the intensity and number of cell communication in each group; (D) Bar chart ranking the importance of signaling pathways in cell communication in each group; (E) Scatter plot illustrating the communication strength of each cell as input/output signal; (F) Scatter plot showing the signaling pathways with differences between groups when Macrophages serve as input/output signal.

Identification of DEGs in HF

After merging the GSE66630 and GSE101977 datasets and standardizing the combined data, a total of 15,871 genes were retained for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). By applying |log2FC| > 1 & p.adjust < 0.05 as screening criterion, we screened out 1,147 DEGs, including 374 up-regulated and 773 down-regulated DEGs (Fig. 4A). Functional analysis of these DEGs revealed that most of them were enriched in actin binding, cell adhesion molecule binding, transmembrane transporter binding, diabetic cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Fig. 4B, C).

Source https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Identification of DEGs in HF. (A) Volcano map showing the results of the differences between groups; (B) GO analysis of DEGs; (C) KEGG analysis of DEGs (KEGG, reproduced with permission from Kanehisa Laboratories.

Weighted gene co-expression network construction

We carried out cluster analysis on all samples (Fig. 5A). Based on independence and average connectivity analysis (Fig. 5B, C), a power of 5 (R2 = 0.77) was selected to generate a weighted gene co-expression network, with the criteria of minimum module of 30 and mergeCutHeight of 0.25 (Fig. 5D). We conducted correlation analysis on sample features (TAC and sham) and modules (Fig. 5E), and with |cor| > 0.8 and P < 0.001, we finally selected the brown module (cor = 0.84, P < 0.001) and blue module (cor = −0.84, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A, B). Functional analysis was performed separately for the crucial genes within each module. Genes within the brown module were primarily enhanced in epithelial cell migration, actin cytoskeleton, actin binding, Rap1 pathway, and cAMP pathway (Fig. 6C, D). In contrast, genes within the blue module were predominantly enriched in ribose phosphate metabolic process, mitochondrial matrix, GTPase regulator activity, and MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 6E, F).

Weighted gene co-expression network construction. (A) Cluster analysis of the samples; (B) Scale-free fitting index and average connectivity analysis with different soft-threshold powers; (C) Visual assessment of scale-free topologies; (D) Weighted gene co-expression networks; (E) Heatmap showing the association between modules and sample characteristics.

Source https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Identification of core genes in modules. (A) Correlation between the brown module gene and HF; (B) Correlation between the blue module gene and HF; (C) GO analysis of core genes in the brown module; (D) KEGG analysis of core genes in the brown module; (E) GO analysis of core genes in the blue module; (F) KEGG analysis of core genes in the blue module. (KEGG, reproduced with permission from Kanehisa Laboratories.

Identification of cuproptosis-related key genes associated with HF

To identify cuproptosis-related genes that impact the occurrence and development of HF, we took intersections of genes from the blue and brown modules, DEGs, and cuproptosis-associated genes, and finally obtained three intersection genes: DBT, Atox1, and DLD (Fig. 7A, B). Expression analysis of these three intersection genes in the bulk dataset demonstrated that the expression of DBT and DLD were notably lower in the TAC group, whereas Atox1 was substantially elevated in the TAC than that in the sham group (Fig. 7C). Consistent with this, analysis of their expression in scRNA-seq datasets showed that Atox1 was more widely distributed and expressed in multiple cells than DBT and DLD (Fig. 7D, E). ssGSEA of the intersection genes indicated that all three genes were related to Citrate cycle (TCA cycle), which is intrinsically linked to the initiation of cuproptosis16 (Fig. 8A–C). Immunoinfiltration analysis revealed significant differences in the following cell populations between groups, Macrophages M2, Dendritic cells resting, Macrophages M1, Dendritic cells activated, Monocytes, Macrophages M0, NK cells resting, and T cells CD4 memory resting (Fig. 8D). Finally, we examined the link between the identified intersection genes and immune cells. Atox1 was demonstrated to be associated with B cells and Monocytes in the sham group (Fig. 8E), while in the TAC group, it was revealed to be correlated with Dendritic cells resting, B cells, Macrophages M0, Monocytes, and Macrophages M1 (Fig. 8F). Our findings suggest that Atox1 may influence the progression of HF by affecting immune cells.

Identification of cuproptosis-related key genes associated with HF. (A) Venn diagram showing the intersection of DEGs, genes from the brown module, and cuproptosis-related genes; (B) Venn diagram showing the intersection of DEGs, genes from the blue module, and cuproptosis-related genes; (C) Box diagram illustrating the expression of intersection genes; (D) UMAP illustrating the distribution of intersection genes in a scRNA-seq dataset; (E) Expression of the intersection genes in scRNA-seq datasets.

Functional analysis of key genes. (A) GSEA results for Atox1; (B) GSEA results for DLD; (C) GSEA results for DBT; (D) Box diagram illustrating differences in immune cells in each group; (E) Correlation between intersection genes and immune cells in the TAC group; (F) Correlation between intersection genes and immune cells in the sham group.

Atox1 is highly expressed in TAC model mice

The aforementioned analysis revealed a widespread distribution of Atox1 in the single-cell dataset, suggesting its potential significant role. Therefore, Atox1 was selected for further mechanistic investigation. To assess its role in HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy at the animal level, we constructed a TAC mouse model. After 28 days of surgery, echocardiography was performed to evaluate cardiac function. Results showed that EF and FS were lowered in the TAC group in comparison to the sham group (Fig. 9A). The heart weight-to-body weight ratio in TAC group was increased (Fig. 9B). HE and Masson staining revealed severe morphological damage and fibrosis in the TAC group (Fig. 9C). Additionally, the expression levels of BNP, β-MHC, and ANP in heart tissue, as well as TNF and IL-6 in serum, were substantially elevated in the TAC compared to the sham group (Fig. 9D, E). The above findings indicated successful establishment of the HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy model. Subsequent qRT-PCR detection revealed that Atox1 expression was substantially higher in the TAC than in the sham group (Fig. 9F), which aligned with the findings of our bioinformatics analysis. Simultaneously, assessment of cuproptosis-related indicators revealed that SLC31A1 and FDX1 were substantially higher in the TAC than in the sham group, accompanied by notable Dlat aggregation (Fig. 9G, H).

Atox1 is highly expressed in TAC model mice. (A) Evaluation of cardiac function using echocardiography; (B) Heart weight-to-body weight ratio; (C) HE and Masson staining showing the pathological injury of myocardial tissue; (D) Expression of β-MHC, ANP, and BNP in cardiac hypertrophy determined using qRT-PCR. (E) Levels of IL-6 and TNF-α determined through ELISA; (F) Dynamic expression of Atox1 at 7, 14, and 28 days after TAC surgery; (G) Protein expression of SLC31A1 and FDX1 in heart tissue determined through WB; (H) Dlat aggregation in cardiac tissue. **P < 0.01.

Atox1 regulates cuproptosis and promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

To examine the role of Atox1 in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, H9c2 cells were treated with 1 µM Ang II to construct a cardiomyocyte hypertrophy model in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 2). It was found that the expression of Atox1 (Fig. 10A), the surface area of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 10B), and the expression of cardiac hypertrophy markers β-MHC, ANP, and BNP (Fig. 10C) were notably increased in the Ang-II group in contrast to the control group. Concurrently, cuproptosis-related key genes FDX1 and SLC31A1 were found to be substantially upregulated in cells in the Ang-II group in comparison to the control group, accompanied by notable Dlat aggregation (Fig. 10D, E). CS1 fluorescence staining further revealed a notable elevation of intracellular Cu⁺ levels in the Ang-II compared with the control group (Fig. 10F). To assess the functional role of Atox1, we knocked down its expression in H9c2 cells (Fig. 10A). In comparison to the Ang-II + si-NC group, we found substantially reduced surface area of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 10B), markedly decreased expression of cardiac hypertrophy markers β-MHC, ANP, and BNP (Fig. 10C), notably downregulated expression of cuproptosis markers FDX1 and SLC31A1, decreased Dlat aggregation (Fig. 10D, E), and lowered intracellular Cu⁺ accumulation in the Ang-II + si-Atox1 group (Fig. 10F) .

Notably, treatment with a cuproptosis agonist elesclomol + CuCl2 (ES) in the Ang-II + si-Atox1 group partially reversed these effects: cardiomyocyte surface area (Fig. 10B) and the expression of β-MHC, ANP, and BNP (Fig. 10C) were increased, FDX1 and SLC31A1 expression were upregulated, Dlat aggregation was enhanced (Fig. 10D, E), and intracellular Cu⁺ levels were markedly restored (as revealed through CS1 staining) compared with the Ang-II + si-Atox1 group (Fig. 10F).

Collectively, these findings indicate that Atox1 promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by regulating intracellular copper homeostasis and cuproptosis-related genes, and that activation of cuproptosis can partially reverse the protective effects of Atox1 knockdown.

Atox1 regulates cuproptosis and promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. (A) Atox1 expression in cells evaluated through qRT-PCR; (B) Cardiomyocyte surface area measured through F-actin staining; (C) ANP, BNP and β-MHC expression in cardiomyocytes determined through qRT-PCR; (D) Protein expression of FDX1 and SLC31A1 in cardiomyocytes assessed by WB; (E) Dlat aggregation in cardiomyocytes; (F) Intracellular Cu⁺ levels detected using the fluorescence probe CS1. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Cuproptosis has been increasingly recognized as a critical factor in the onset and progression of several cardiovascular diseases, including HF, atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, and arrhythmia6. As previously reported, copper chelator can alleviate these cardiovascular diseases by inhibiting copper reduction pathways17,18. Bioinformatics-based research have further indicated that sepsis promotes the change of cuproptosis-related genes LIAS and PDHB in cardiomyocytes19, thereby inducing cuproptosis and contributing to cardiotoxicity20. Moreover, cuproptosis in diabetes has been revealed to induce myocardial damage18. Therefore, targeting cuproptosis may represent a promising therapeutic strategy to ameliorate HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy.

In this study, three cuproptosis-related genes (DBT, Atox1 and DLD) were identified as potential factors affecting cardiac hypertrophy in HF through bioinformatics analysis. DBT, a subunit that makes up the enzyme complex in mitochondria, has been reported only in neurodegenerative diseases and renal cell carcinoma but has not yet been investigated in cardiovascular diseases. According to relevant studies, DBT acts as a potent inhibitory factor, and its absence promotes the clearance of ubiquitination proteins, thereby protecting the proteasome and inhibiting related cell death. In addition, DBT can change the metabolic and energy status of cells, and activate autophagy by an AMPK-dependent mechanism under conditions of proteasomal inhibition21. Moreover, DBT expression inhibits the invasion of renal cell carcinoma via the Hippo signaling pathway regulated by the ANXA2/YAP axis22,23. DLD is a component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and has been shown to participate in cardioprotection during ischemic post-treatment24. Ginsenoside Rg3 was found to reduce the 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation levels of DLD, restore the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and consequently ameliorate cardiac hypertrophy induced by TAC25. Our data demonstrates that both DBT and DLD play essential roles in the onset and progression of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy, and their expression levels may serve as potential biomarkers for predicting disease onset and progression. Atox1 functions as a copper chaperone responsible for the transfer of absorbed copper ions into cells, thus ensuring cellular copper homeostasis. Recent evidence indicates that Atox1 positively regulates the cuproptosis marker SLC31A1 in mouse cochlear hair cells26. Based on these findings, we concluded that Atox1 can regulate cuproptosis. However, to date, the involvement of Atox1 in cardiovascular diseases has not been reported.

Increasing data have highlighted the significant role of immune regulation in the pathogenesis and development of HF. Accordingly, we conducted an immunoanalysis of samples from each group, which revealed distinct variations in dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells across the groups. Dendritic cells are important inflammatory cells significantly involved in cardiac repair27. Numerous studies have confirmed that MCS-18, a natural product obtained from Helleborus purpurases, reduces the expression of dendritic cells in experimental autoimmune myocarditis, thereby mitigating inflammation and left ventricular remodeling in acute myocarditis28. Cardiac resident macrophages, a heterogeneous population of immune cells, contribute to angiogenesis and inhibit fibrosis under cardiac stress overload29. As reported, Nuanxinkang exerts cardioprotective effects by modulating the polarization of IKβ /IκBα/ NF-κb-mediated macrophages30. Moreover, the allogenic cardiac patch comprising cardiomyocytes and human fibroblasts on a bioresorbable matrix has been shown to induce the infiltration of macrophages and dendritic cells to restore left ventricular contractility31. Our cell-cell communication analysis further indicated that the CCL signaling pathway mediates macrophage interactions with other cells, potentially delaying the occurrence and development of HF or providing a therapeutic target. Previous studies have reported that the cuproptosis inhibitor TTM suppresses MCP-1/CCL2 expression in the aorta of atherosclerotic mice, thereby inhibiting M1 macrophage accumulation in the aorta32. Our bioinformatics analysis revealed a positive correlation between Atox1 and M1 macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting a potential link between Atox1-driven cuproptosis and immune cell infiltration in HF. Future studies are warranted to elucidate whether Atox1 directly modulates macrophage polarization and CCL signaling. T cells have a significant function in immunotherapy. In the early stages of cardiac injury, regulatory T cells suppress excessive inflammatory response and promote stable scar formation, which is beneficial to the heart33. Conversely, inhibition of regulatory T cells aggravates myocardial injury34, whereas suppression of CD8+ T cells alleviates inflammatory injury and improves cardiac function following myocardial ischemia35. Correlation analysis demonstrated that Atox1 correlated with monocytes, B cells, macrophages (M0 and M1), and dendritic cells in the TAC group, suggesting that Atox1 may regulate immune cells to attenuate HF. Additionally, cell-cell communication analysis showed that monocytes exhibited the most pronounced changes in communication intensity between the disease and control groups. In future research, further investigation into the regulatory interplay between Atox1 and monocyte are needed.

Based on bioinformatics analysis results and the existing research findings, Atox1 was selected for subsequent experimental detection to elucidate its mechanism of action. In this study, we identified Atox1 as a cuproptosis-related gene critically involved in HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that Atox1 modulates cuproptosis and promotes the occurrence of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy. Nevertheless, this study still has certain limitations. We plan to further verify the regulatory mechanism of Atox1-mediated cuproptosis by employing copper chelator in vitro, and to collect more clinical samples to determine Atox1 expression in both patients with healthy and HF groups. Additionally, this study was primarily conducted using the H9c2 cardiomyoblast cell line. Although this model is well-established and highly valuable for initial mechanistic investigations, future validation in primary cardiomyocytes or in vivo models would enhance the clinical relevance of our findings. These efforts are expected to enhance our understanding of the mechanism underlying HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy and present a novel therapeutic target for the clinical treatment of HF-associated cardiac hypertrophy.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were downloaded and analyzed in this study, which can be found in the GEO data repository, with accession numbers as follows: GSE101977 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE101977), GSE66630 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE66630) and a single-cell dataset GSE122930 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE122930). Raw data for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yuan, H. J., Xue, Y. T. & Liu, Y. Cuproptosis, the novel therapeutic mechanism for heart failure: a narrative review. Cardiovasc. Diagnosis Therapy. 12 (5), 681–692 (2022).

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 141 (9), e139–e596 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Ablation of LncRNA Miat attenuates pathological hypertrophy and heart failure. Theranostics 11 (16), 7995–8007 (2021).

Martin, T. G., Juarros, M. A. & Leinwand, L. A. Regression of cardiac hypertrophy in health and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20 (5), 347–363 (2023).

Moon, M. G. et al. Reverse remodelling by sacubitril/valsartan predicts the prognosis in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 8 (3), 2058–2069 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. The molecular mechanisms of cuproptosis and its relevance to cardiovascular disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 163, 114830 (2023).

Tian, Z., Jiang, S., Zhou, J. & Zhang, W. Copper homeostasis and Cuproptosis in mitochondria. Life Sci. 334, 122223 (2023).

Wu, C., Zhang, Z., Zhang, W. & Liu, X. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial therapies in heart failure. Pharmacol. Res. 175, 106038 (2022).

Zhuang, L. et al. DYRK1B-STAT3 drives cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure by impairing mitochondrial bioenergetics. Circulation 145 (11), 829–846 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Restoration of myocellular copper-trafficking proteins and mitochondrial copper enzymes repairs cardiac function in rats with diabetes-evoked heart failure. Metallomics 12 (2), 259–272 (2020).

Kong, B. et al. Sirtuin3 attenuates pressure overload-induced pathological myocardial remodeling by inhibiting cardiomyocyte Cuproptosis. Pharmacol. Res. 216, 107739 (2025).

Heng, T. S. & Painter, M. W. The immunological genome project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 9 (10), 1091–1094 (2008).

Aran, D. et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20 (2), 163–172 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–d7 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Tsvetkov, P. et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Sci. (New York NY). 375 (6586), 1254–1261 (2022).

Itoh, T., Haruna, M. & Abe, K. Differential regulation of the nitric oxide-cGMP pathway exacerbates postischaemic heart injury in stroke-prone hypertensive rats. Exp. Physiol. 92 (1), 147–159 (2007).

Huo, S. et al. ATF3/SPI1/SLC31A1 signaling promotes Cuproptosis induced by advanced glycosylation end products in diabetic myocardial injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(2), (2023).

Sun, Z. et al. Bioinformatics reveals diagnostic potential of cuproptosis-related genes in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Heliyon 10 (1), e22664 (2024).

Yan, J., Li, Z., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Sepsis induced cardiotoxicity by promoting cardiomyocyte cuproptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 690, 149245 (2024).

Hwang, R. D. et al. DBT is a metabolic switch for maintenance of proteostasis under proteasomal impairment. BioRxiv (2024).

Lai, S. W. et al. Underlying mechanisms of novel cuproptosis-related Dihydrolipoamide branched-chain transacylase E2 (DBT) signature in sunitinib-resistant clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 16 (3), 2679–2701 (2024).

Miao, D. et al. N6-methyladenosine-modified DBT alleviates lipid accumulation and inhibits tumor progression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma through the ANXA2/YAP axis-regulated Hippo pathway. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 43 (4), 480–502 (2023).

Cao, S. et al. Ischemic postconditioning influences electron transport chain protein turnover in Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. PeerJ 4, e1706 (2016).

Ni, J. et al. Rg3 regulates myocardial pyruvate metabolism via P300-mediated Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. Death Dis. 13 (12), 1073 (2022).

Chen, X., Xiang, W., Li, L. & Xu, K. Copper chaperone Atox1 protected the cochlea from cisplatin by regulating the copper transport family and cell cycle. Int. J. Toxicol. 43 (2), 134–145 (2024).

Martins, S. et al. Role of monocytes and dendritic cells in cardiac reverse remodelling after cardiac resynchronization therapy. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 558 (2023).

Pistulli, R. et al. Characterization of dendritic cells in human and experimental myocarditis. ESC Heart Fail. 7 (5), 2305–2317 (2020).

Revelo, X. S. et al. Cardiac resident macrophages prevent fibrosis and stimulate angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 129 (12), 1086–1101 (2021).

Dong, X. et al. Nuanxinkang protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced heart failure through regulating IKKbeta/IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB-mediated macrophage polarization. Phytomedicine 101, 154093 (2022).

Lancaster, J. J. et al. Biologically derived epicardial patch induces macrophage mediated pathophysiologic repair in chronically infarcted swine hearts. Commun. Biol. 6 (1), 1203 (2023).

Wei, H., Zhang, W. J., McMillen, T. S., Leboeuf, R. C. & Frei, B. Copper chelation by tetrathiomolybdate inhibits vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 223 (2), 306–313 (2012).

Lu, Y., Xia, N. & Cheng, X. Regulatory T cells in chronic heart failure. Front. Immunol. 12, 732794 (2021).

Feng, G. et al. CCL17 aggravates myocardial injury by suppressing recruitment of regulatory T cells. Circulation 145 (10), 765–782 (2022).

Forte, E. et al. Cross-Priming dendritic cells exacerbate immunopathology after ischemic tissue damage in the heart. Circulation 143 (8), 821–836 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Planning Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2025ZR073).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hui Zhou performed the bioinformatics analysis and designed the experimental protocol. Ming Yang and Hongfeng Jin performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. Hui Zhou and Hongfeng Jin drafted the manuscript. Ziqing Ye revised the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the manuscript and discussed, reviewed, and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This animal study was carried out in strict compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang Center of Laboratory Animals (No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20020190). All experimental procedures were strictly in accordance with the relevant provisions of the National Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Approval was granted by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang Center of Laboratory Animals (No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20020190).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Yang, M., Jin, H. et al. The effect of cuproptosis-related gene Atox1 on cardiac hypertrophy in heart failure was investigated based on bioinformatics analysis. Sci Rep 15, 44715 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28342-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28342-6