Abstract

The carbon contact strip of pantograph collects current from the overhead catenary to power the train, inevitably causing wear to the contact surface. This paper addresses the abnormal wear of the pantograph carbon contact strip, a challenged accident encountered in operation and maintenance. This issue involves aspects of tribology, dynamics interaction, and electrical contact, making it difficult to explain from a single perspective. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using field testing, laboratory experiments, and simulation, focusing on frequency matching, dynamic interaction, and wear performance. The results revealed that during operation, a frequency mismatch between the pantograph and the catenary led to the activation of the problem during dynamic interactions. This instability resulted in a reduced contact area, increased contact stress, and a sharp rise in current density, all of which contributed to higher wear rates and abnormal profiles of the contact surface. Furthermore, these changes, along with the reduced environmental humidity, further deteriorated the wear and dynamic performance of the system. Subsequent structural and parameter adjustments can optimize this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pantograph-catenary system (PCS) is the sole means of power supply for electrified trains and is one of the critical subsystems for ensuring the safe and stable operation of trains. In contemporary electrified railway systems, the primary forms of train power supply system include the overhead flexible catenary, the overhead rigid catenary, and the third rail. Given the economic benefits and operational conditions of metro lines, the overhead rigid catenary has become the preferred power supply system for urban rail transit1. The pantograph, mounted on the roof of the train, collects current through sliding contact with the contact wire, which is arranged in a sinusoidal pattern along the track centerline to prevent continuous friction at a certain location on the carbon strip.

The dynamic interaction of PCS is highly complex under electric contact conditions of high relative sliding velocity. Fluctuating loads can easily cause fatigue damage to components such as the suspension mechanism2,3,4 and the framework5,6,7, jeopardizing operational safety. More critically, when contact is lost, severe offline arcing may occur8,9, significantly damaging the smoothness of the contact surface and leading to severe wear of the contact pair. Recently, abnormal wear of PCS contact pair has become a serious issue in China10,11,12. This phenomenon causes two main problems. Firstly, the wear rate increases dramatically, as shown in Fig. 1. This data is sourced from a specific metro line, which uses a rigid suspension catenary system and has a maximum operational speed of 120 km/h. Before December 10, the wear rate remained relatively stable at approximately 1.3 mm/104 km. However, due to abnormal matching performance and a sudden decrease in ambient humidity, the wear rate surged after December 10, peaking at 43.59 mm/104 km, more than 40 times higher than normal, resulting in significant damage to daily operations, including economic losses. This abnormal wear persisted for about three weeks and returned to normal after corrective measures were taken. Secondly, during this period, there were significant irregularities in the profiles of the carbon strip and contact wire, as shown in Fig. 2. Specifically, the pantograph carbon strip exhibited groove abnormal wear on the right side of the upward direction, between 200 and 240 mm (with the lowest point at 220 mm). Additionally, copper powder and copper wire were found on some train roofs. Simultaneously, inspections of the catenary revealed abnormal wear at certain rigid anchor sections, along with signs of scratches and arcing on the contact wire surface. These surface anomalies were observed in areas with higher stagger values or higher current levels.

The issue of abnormal wear is complex and multifaceted. From a tribological perspective, the deterioration in wear performance may be attributed to changes in operational parameters. As operating speed increases, the vibration of the PCS contact pair inevitably intensifies, leading to an increase in dynamic contact force amplitude and arcing energy, which subsequently raises the wear rate of the carbon strip13,14. When the relative sliding velocity exceeds 300 km/h, damage to the carbon strip morphology becomes more severe, with an increase in wear debris, further accelerating the wear rate15. Additionally, the static contact force of the PCS contact pair plays a significant role in balancing electrical and mechanical wear1. Typically, the wear rate of the carbon strip shows an initial decrease followed by an increase as normal force rises16,17,18,19. Mishina and Hase20 found that as adhesive forces increase, the volume of element transfer also increases. More importantly, the impact of electrical current is substantial, often leading to a several-fold increase in the wear rate. From a dynamic perspective, changes in the structure and parameters of PCS significantly affect its dynamic characteristics21,22 and the geometric relationship of the rods23, which further affects the dynamic interaction. A deterioration in parameters such as compliance and frequency matching can severely degrade the current collection performance24, potentially leading to local resonance effects that cause violent shocks, resulting in direct damage to the carbon strip, such as block detachment or pitting. From the perspective of electrical contact, the degradation of contact characteristics is closely linked to factors such as current density25, operational conditions26, the distance over which offline arcing occurs27, and material properties28,29,30, as they significantly affect the contact resistance, arcing intensity and duration. Specifically, the instantaneous high temperatures generated by the offline arcing, which influence material properties and wear performance, should not be overlooked13,31,32.

From the perspective of tribology, the study conducted still fails to address the underlying causes of abnormal wear rate and abnormal wear profile due to the complexity and randomness of the PCS12,31,32. Additionally, based on the aforementioned research, the operating company had also made appropriate adjustments to certain parameters from different perspectives. However, the results appear to be limited, as this issue is likely not caused by a single factor. Furthermore, this complex and critical problem involves the collaboration of multiple disciplines and departments, including the vehicle, power supply, and engineering departments, making the research particularly challenging. There is still a lack of a multidisciplinary analytical approach to investigate this complex issue.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section "Multidisciplinary analysis methods on PCS abnormal wear" elaborates on the logical structure of this study. Section "Analysis of PCS frequency matching" reviews existing research on frequency matching, encompassing both static and dynamic modalities. Section "Simulation and analysis of PCS dynamic interaction" provides a dynamic simulation analysis of PCS, exploring the changes in dynamic performance after abnormal wear occurs in the contact surface and explaining the development of this abnormal wear. Section "Wear test of PCS contact pair" investigates the evolution of contact wear characteristics under the influence of current density, providing data support for this study. Section "Comprehensive correlation analysis and further discussion of abnormal wear" provides a comprehensive discussion on the correlation of the aforementioned works and summarizes the causes and deterioration process of abnormal wear. The main conclusions are presented in Section "Comprehensive correlation analysis and further discussion of abnormal wear".

Multidisciplinary analysis methods on PCS abnormal wear

Abnormal wear in PCS is a typical interdisciplinary challenge, with its causes and evolutionary mechanisms involving the coupled effects of tribology, dynamics, electrical contacts, and materials science. Traditional single-disciplinary theoretical frameworks are insufficient to fully reveal its complex nature. Therefore, this paper systematically decomposes the issue into several key dimensions and adopts a multi-method research strategy to progressively identify its underlying mechanisms. The specific research content and methodology are illustrated in Fig. 3. Specifically, through field testing and modal testing, the dynamic performance and frequency matching characteristics of PCS under the integration of multiple factors are examined. Simulation analysis is then conducted to further investigate the relationship between dynamic interaction and wear profile in PCS. Finally, tribological laboratory testing is employed to assess the wear performance of contact pair. Each part supports the others, aiming to cross-verify from multiple angles and systematically identify the root causes of abnormal wear in PCS.

Analysis of PCS frequency matching

This section analyzes the frequency matching between the two primary structures of PCS. The objective is to determine whether frequency matching anomalies occur during actual railway operation. The investigation comprises two parts: field test of the PCS dynamic interaction and static modal testing of PCS.

Field test of the PCS dynamic interaction

To investigate the vibration characteristics of the pantograph-catenary system, field tests were conducted, which complied with the EN 50367 and EN 50119 standards. Given safety concerns and the need for accurate measurements, the dynamic behavior of the pantograph was assessed by measuring the acceleration of the contact strip. Based on previous studies, the primary characteristic frequencies of the pantograph are distributed between 0 and 100 Hz3,32. A triaxial sensors were arranged at the suspension position of the pantograph collector head, as shown in Fig. 4. The cables of sensor, which provided power and transmitted signals, were embedded in insulated tubes on the frame of pantograph. The data acquisition system was installed on the pantograph’s base frame, with appropriate insulation measures. Data were transmitted via optical fiber to the main data acquisition system inside the train for real-time monitoring and subsequent data processing, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Additionally, the collection of geometric parameters and other data is based on a non-contact multi-source data acquisition system, as shown in Fig. 27 of Appendix 1.

During the field tests, the train operations mirrored actual operation conditions, including passenger load. Therefore, each segment of the journey involved three phases: acceleration, constant speed, and deceleration to a stop. The stagger values, speed, and current data were simultaneously collected from the onboard system. Data were collected throughout an entire day, from the departure of train in the early morning to its return at night. Each instance of train start and stop was treated as a separate data set for analysis, resulting in a large amount of data, which facilitated the vibration characteristic analysis and the extraction of characteristic frequencies. Figure 5 shows the time-history curve for a specific segment, where it is evident that the acceleration amplitude increases with operating speed. Furthermore, during start and stop phases, the load current significantly increases. Additionally, the vertical acceleration of the strip is slightly higher than the lateral acceleration. The vibration data presented in Fig. 5 are the response data, while the remaining parameters—stagger, operating speed, and current—are inputs recorded during actual operation.

Subsequently, a power spectral density (PSD) analysis was conducted to identify the dominant characteristic frequencies. PSD analysis is a classical method for analyzing random vibrations and identifying structural dynamic characteristics. Given the frequent starts, stops, and complex operational conditions during actual train running, the PSD was estimated using Welch’s method. The results are presented in Fig. 6.

The vertical vibration signal at the test position of the strip exhibits a distinct peak at 58.59 Hz. In the PSD results of the lateral vibration signal at the same position, a prominent peak is observed at 78.13 Hz. Most of the other peaks also correspond to the structural frequencies of the PCS, which can be identified in subsequent static modal testing in Section "Simulation and analysis of PCS dynamic interaction" and simulation results in Appendix 1.

Static modal testing of PCS

This section presents the results of static modal testing on the pantograph and overhead catenary, utilized in the actual line, to determine the natural frequencies and explore the corresponding vibration modes. These results are then compared with the integrated vibration field test data of PCS from actual tracks to verify whether the vehicle experiences local resonance due to the proximity of modal frequencies, leading to abnormal wear on the contact pair.

Static modal testing of pantograph

Experimental modal analysis was employed in this section. A stable impact hammer excitation was applied as the input signal to the system, while a data acquisition system was used to record the output response. The frequency response function (FRF) was then derived from the input and output signals using an estimation algorithm. Finally, the modal parameters of the system were identified by fitting the FRF data with a known modal equation.

During the experiment, the frequency response function Hij(w), defined as the ratio of the response at point i to the excitation applied at point j, is expressed as:

where Hij = Hji, {F} = [F1, F2, … Fn]T, the obtained acceleration signal Xi = [Hi1, Hi2, … Him]{F1, F1, …Fn}T.

The FRFs Hij(w) between all response points and excitation points are arranged in a matrix to form the FRF matrix:

For an N-degree-of-freedom system with proportional damping, the forced vibration response is given by:

where φ is the mass-normalized mode shape vector for the mode, mr, kr, cr are the modal mass, stiffness, and damping parameters for the rth mode, w is the excitation frequency.

Therefore, the frequency response function matrix can be expressed in modal coordinates as:

As shown in the preceding equations, each row vector of the frequency response function (FRF) matrix contains all the modal parameters of the tested system. Furthermore, the ratio of the frequency response functions for the rth mode between any two row vectors directly yields the mode shape for that mode.

Consequently, modal testing was conducted on both the pantograph and the rigid catenary in this section. The first step involves selecting the modal measurement points, ensuring that these points avoid modal frequency aliasing and correspond to locations where the vibration modes are not at nodes. To accurately capture the vibration modes of structure, 22 measurement points were placed on the pantograph frame, and 20 points were positioned on the leaf spring and strip, as shown in Fig. 7. The modal test pantograph was consistent with the pantograph actually used in the line and the testing process was shown in Fig. 8. Specifically, 22 points on the pantograph frame were impacted vertically, and 18 points were impacted laterally. The suspension system and strip had 20 vertical and 8 lateral impact points. Acceleration responses of the structure and force signals from the impact hammer were recorded, and transfer functions were calculated to obtain the modal vibration modes.

The results of vibration modes are shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11, which are vertical of the pantograph collector head, vertical and transverse of the upper frame, respectively.

The first six modes are as follows: the first bending mode of the leaf spring, the first reverse rotational mode of the strip, the first forward bending mode of the strip, the first reverse bending mode of the strip, the second forward bending mode of the strip, and the third forward bending mode of the strip.

The first six modes are as follows: the first forward bending mode, the local bending mode, the second forward bending mode, the second reverse bending mode, the third and fourth bending mode.

The first six modes are as follows: the first reverse horizontal bending mode, the first forward horizontal bending mode, the second reverse horizontal bending mode, the first forward horizontal bending mode, the third forward horizontal bending mode, and the third reverse horizontal bending mode.

Static modal testing of catenary

Due to experimental constraints, the modal testing on the rigid catenary system was conducted on a segment with significant wear. This choice is representative because of the structural consistency. The span in this section is 8 m, with a total of 17 measurement points arranged at 0.5-m intervals. The locations of the measurement points and sensors are shown in Fig. 12. The test procedure follows the same protocol as depicted in Fig. 8.

The results of vibration modes are shown in Fig. 13. It is the first to sixth order vertical bending of this section, respectively.

Modal frequency comparison of pantograph and catenary

Table 1 presents the modal characteristic frequencies of the pantograph head, frame, and catenary system. The purpose is to compare whether modal overlap exists statically, which could lead to resonance effects. Additionally, this data supports the characteristic frequencies presented in Section "Multidisciplinary analysis methods on PCS abnormal wear".

The first vertical bending mode of the pantograph head strip (21.02Hz) is similar to the second vertical bending mode of the catenary system (22.58Hz) , while the second frequency of the pantograph head strip (42.08Hz) is close to the third vertical bending mode of the catenary system (41.38) . This overlap can induce local resonance effects, leading to instability in the PCS. Moreover, this frequency was observed in the dynamic interaction field tests. Additionally, a prominent peak in the vertical vibration signal of the strip was found at 58.6 Hz, corresponding to the pantograph head strip the fourth natural frequency. The lateral frequency of 78.1 Hz observed in the dynamic field test acceleration corresponds to the first lateral bending mode of the frame (75.18 Hz), indicating that this mode was excited during operation, leading to local resonance. This resonance is responsible for abnormal contact conditions and instability in the friction system. Considering the results above, it was found that the natural frequencies of other pantograph models on the same line did not match those of the catenary system, and no severe abnormal wear was observed. Therefore, frequency mismatch is one of the key factors contributing to abnormal wear. Adjustments to the pantograph-catenary structure are necessary to prevent this issue.

Furthermore, Fig. 6 in Section "Multidisciplinary analysis methods on PCS abnormal wear" demonstrates that certain frequency components were not excited during the modal testing. Therefore, a simulation analysis was conducted to further investigate the complete mode shape characteristics, with the results presented in Fig. 28 of Appendix 1.

Simulation and analysis of PCS dynamic interaction

This section discusses the evolution law of the dynamic performance of PCS with the abnormal profile of the pantograph strip, which has shown in Fig. 2. This section can provide data support for the subsequent analysis of wear performance.

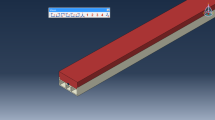

The catenary model is established using the finite element method, while the pantograph model employs a hybrid rigid-flexible model (the same model utilized in the actual line)1, with the sliding contact strip modeled as a flexible body to better capture higher flexible frequencies and actual contact states (the grooves that conform to the actual dimensions are manufactured through the finite element model). The corresponding theoretical derivation can be found in Appendix 2. The contact algorithm utilizes a flexible surface contact model based on the polygonal contact method (PCM)33. The contact force calculation follows a one-dimensional penalty function model based on Hertzian contact theory34, where the magnitude of the contact force is a function of the penetration depth δ and penetration velocity , as shown in Eq. (1), the total contact force is determined by summing the normal forces calculated at each contact point34, as shown in Eq. (2). The verification of the dynamic model is presented in Appendix 1.

where k and c are the stiffness and damping coefficients, respectively. δ is the penetration depth, and m1, m2, and m3 are the stiffness exponent, damping exponent, and indentation exponent, respectively.

The consideration of the strip profile grooves, with cross-sectional parameters identical to those of the actual strip surface, are fabricated on the finite element method. The finite element model of the strip is then integrated with the pantograph model. To better reflect dynamic characteristics, grooves are placed at the center of the strip (at a stagger value of 0 mm) and at positions 220 mm on either side of the center (with a stagger value ± 220 mm). The groove width is set to 40 mm, and the depth ranges from 0 to 5 mm, as shown in Fig. 14. Figure 15 presents a schematic diagram of the actual grooves in the strip, with groove widths approximately 40 mm.

In the simulation, the catenary was configured with a sinusoidal layout, with a stagger value ranging from − 250 mm to + 250 mm. The operational speed was set to 60 km/h, and the static uplift force was 120 N. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 16. During pantograph operation, when the contact point is at a groove location, the contact force and acceleration exhibit significant fluctuations. Considering a periodic contact phenomenon between the contact wire and the grooves on the strip surface, signifying a cyclical degradation of the contact state. The contact force and acceleration exhibit significant fluctuations at the locations where the grooves intersect with the strip. When the groove depth of the strip is between 0 and 2 mm, there is no noticeable change in the contact force. However, the acceleration of the sliding plate increases when the wear depth reaches 2 mm. As the groove depth increases, the maximum contact force (Fmax) rises from 131.88 N to 395.65 N, an increase of more than three times. Additionally, the standard deviation of the contact force (Fstd) increases from 14.39 N to 26.81 N, and the offline rate rises from 0% to 0.8%, indicating a sharp deterioration in the dynamic interaction quality, as shown in Fig. 17. In Fig. 16b, the maximum acceleration increases from 0.43 m/s2 to 7.43 m/s2, suggesting that the contact force and pantograph dynamics worsen with the increasing groove depth. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 17, when the groove depth exceeds 3 mm, the Fmax surpasses 300 N, exceeding the EN50119 standard for Fmax. This is accompanied by the appearance of offline, with the offline rate and the severity of offline occurrences increasing as the groove depth increases.

During the relative sliding electrical contact between the pantograph and catenary, wear of the contact surfaces increases with the normal force. As the contact force at the grooves exceeds 300 N, it further deteriorates current collection performance, leading to more severe wear. Additionally, with increasing groove depth, offline arcing occurs, which causes erosion of the arcing. This results in both direct electrical wear, which is quite severe, and the generation of high temperatures that degrade the contact surface, leading to increased wear debris, as indicated by the wear model widely used at present, as shown in Eq. (3) 17. Consequently, adhesive and abrasive wear are exacerbated. Thus, the occurrence of arcing contributes to both electrical and mechanical wear, a phenomenon that is particularly noticeable in low-humidity environments12. This is one of the key factors contributing to abnormal wear of the strip.

where k1 represents the mechanical wear coefficient, α denotes the dependency of mechanical wear on current intensity, β indicates the dependency of mechanical wear on the normal force, k2 is the current wear coefficient, and k3 is the arc ablation wear coefficient. Fm (N) refers to the average normal force, F0 (N) is the reference value of the normal force, Ic is the nominal value of current intensity (A), I0 (A) is the reference value of current, V represents the sliding velocity (m/s), Rc (Ω) is the contact resistance between the carbon strip and the contact wire, u is the contact loss percentage, H (N/mm2) is the material hardness, Hm (J/kg) is the latent heat of fusion, ρ (kg/m3) is the material density, Va (V) is the arc voltage.

Wear test of PCS contact pair

Section "Wear test of PCS contact pair" has discussed the changes in the dynamic performance of PCS when grooves are present on the strip. These changes are characterized by increased fluctuations in contact force and acceleration, as well as a rise in Fmax, which inevitably leads to an increase in contact stress and severe wear. On the other hand, when the pantograph moves over the edges of the grooves, there is a noticeable reduction in the generalized contact area between the contact surfaces. Additionally, the rapid vertical displacement at the groove edges causes a loss of contact between the strip and contact wire, intensifying arcing and vibrations at the pantograph collector head. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a detailed wear performance study to provide meaningful insights into the issue of abnormal wear.

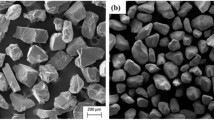

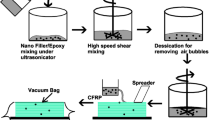

During the normal wear cycle, the contact area is characterized by surface-to-surface, as illustrated in Fig. 18. When the friction system becomes unstable, the contact area significantly decreases (Fig. 18 a shows that lateral eccentric wear leads to grooves, reducing the effective contact area, similar to Fig. 2. Figure 18b demonstrates that longitudinal eccentric wear and pantograph head longitudinal rotation further reduce the effective contact area, akin to Fig. 18a). Under a constant static lifting force, the normal load increases, and the wear volume rises proportionally with the normal load20,35,36. On the other hand, as the contact area decreases, the current density increases under the same electrical load. The wear rate increases exponentially with the current16,17. To quantify this issue, wear tests were conducted using strips made from the same material as the ones used in the field. The test machine was a laboratory-built ring-block tester12, with a normal load of 120 N, a sliding speed of 60 km/h, and current densities ranging from 0 to 2.5 × 10⁶ A/m2(The actual is about 1.83 × 106A/m2). Each experiment involved sanding the contact wires and strips both longitudinally and transversely (relative to the direction of rotation) with 800# and 1500# sandpaper in sequential order. After each sanding, the surfaces were rinsed and wiped with 95% alcohol to remove any residual debris and foreign particles. Figure 19a,b show the schematic diagram and data acquisition system of the machine, respectively.

Test machine and data acquisition system. (a) 1. Test machine construction frame, 2. Variable-frequency motor, 3. Contact pairs, 4. Insulator, 5. Vertical reciprocating frame, 6. Pulley, 7. Normal force loading device 8. Temperature and humidity detector, 9. Mercury, 10. Industrial grade dehumidifier, 11. Environmental room.

Figure 20 presents the experimental results along with the corresponding fitting equations. Based on the wear prediction model proposed in16, which is derived from energy dissipation, the wear rate is a quadratic function of the current. Therefore, a quadratic fitting function is applied to model the wear rate, and the same approach is used for the arcing energy. Figure 20d shows a linear relationship. The key conclusion drawn is that, as the contact area decreases and the relative current density increases, the wear rate increases exponentially. When the current density reaches 2.5 × 10⁶ A/m2, the wear rate increases by a factor of 957.14 compared to the non-current-carrying state, and by a factor of 8.58 under low-load current density conditions. As a result, the increase in current density leads to higher arcing energy, which significantly amplifies the adhesive effects at the contact surface, intensifying material transfer and causing severe wear.

To further validate this conclusion, the central area of the post-experiment samples was selected for microstructural and elemental composition analysis, as shown in Figs. 21, 22, 23. Figure 21 presents the microstructure of the strip sample after testing under experimental conditions of 2.5 × 10⁶ A/m2. Figure 21a shows the macroscopic morphology of the sample after testing, where traces of arcing ablation are clearly visible. SEM analysis of the central area reveals significant damage from arcing ablation on the surface, as well as some debris, as shown in Fig. 21b,c. Elemental composition analysis of Fig. 21d reveals key insights into the wear mechanism and elemental distribution, as shown in Figs. 22 and 23. C is the most abundant element, accounting for 53.4%, followed by O and copper Cu. Additionally, comparing Figs. 21d and Fig. 23c show that the distribution of splattered material on the surface closely matches the distribution of O. Notably, there is significant overlap between O and C in the surrounding area, suggesting that the surrounding block-like and filamentous materials are oxides of carbon. In contrast, O and Cu exhibit overlap in the central area, where the spherical particles are identified as copper oxides. These findings suggest that the splatter resulting from arcing ablation is primarily due to the interaction between Cu and O, or C and O. The splattered material adheres to the surface of the strip, increasing surface roughness and thereby enhancing mechanical wear. Additionally, the low electrical conductivity of copper oxide hinders current transmission, reducing the actual contact area of micro-protrusions that would typically make contact. This may lead to the formation of an arcing breakdown gap, increasing the likelihood of arcing formation and further intensifying both mechanical and electrical wear on the strip. This phenomenon intensifies with increasing current density.

Comprehensive correlation analysis and further discussion of abnormal wear

The issue of current-carrying frictional wear in PCS involves multiple factors, including mechanical structure, dynamics, thermodynamics, and tribology, making it highly complex. Therefore, a multifactorial approach must be adopted during the analysis process. This study conducted an analysis of the abnormal wear of the pantograph contact strip through combined simulation and experimental approaches from frequency matching, dynamic interaction and wear performance, respectively. The analysis primarily addresses two key issues: abnormal wear profiles and the sudden increase in wear rate.

The first step is to analyze the causes of abnormal wear profiles. Due to the frictional system formed by the strip and contact wire, relative sliding friction exists both longitudinally (along the direction of train operation) and laterally. As a result, the eccentric wear phenomenon, specifically the formation of grooves, should be explained by decomposing the contact zone of the pantograph strip in the lateral direction for further analysis, as shown in Fig. 24. Previous studies18,19 have demonstrated that the contact force and wear volume differ across various sections, as determined through simulations or numerical calculations. To more accurately reflect the wear and force conditions in each section, this study utilizes statistical analysis based on data collected from the actual operation in Section "Multidisciplinary analysis methods on PCS abnormal wear", as shown in Fig. 25. It is evident that at stagger values of 200 ~ 240 mm as indicated by larger standard deviations in acceleration and higher average acceleration values. In addition, the average current is also higher. When the system operates under these conditions over time, localized excessive wear occurs in these sections, leading to the formation of grooves. The specific cause is the presence of abnormal vibrations in this area, which indicates an intensification of coupled vibrations. This, in turn, increases the quantity of debris and the likelihood of crack formation, thereby accelerating mechanical wear. On the other hand, the intensification of coupled vibrations leads to abnormal contact states in the contact pairs, resulting in fluctuations in contact resistance. An increase in contact resistance causes a sharp rise in Joule heating and the potential for increased arcing, further exacerbating electrical wear. This is particularly pronounced because the current in this area is significantly higher than in other areas. Consequently, more severe wear occurs here, with some areas further developing into grooves. Based on the simulation results in Section "Wear test of PCS contact pair", the presence of grooves further deteriorates dynamic performance, intensifying fluctuations in contact force and acceleration. Additionally, the increased vibration results in more wear debris, exacerbating mechanical wear. Furthermore, according to the wear prediction model as shown in Eq. (3) 16, an increase in force and current causes a rise in wear rate in these sections, while intensified vibrations further contribute to the accumulation of wear debris, worsening mechanical wear. Consequently, the grooves progressively deepen. Particularly when the groove depth exceeds 2 mm, the increase in Fmax and arcing exacerbates the deterioration of the grooves.

The second aspect investigates the causes of abnormal wear rate. Based on the overall analysis results and collected data, three key factors can be identified as potential contributors: frequency matching, dynamic interaction, and wear performance. Frequency matching analysis, including tests on the dynamic interaction of PCS field test, as well as the static modal testing on the pantograph and the catenary, reveals that the natural frequency of the pantograph is close to the second and third natural frequencies of the catenary, which are also manifested during operation, leading to local resonance effects and the deterioration of matching performance. On one hand, abnormal contact conditions result in changes to the actual contact area, causing increased fluctuations in local contact stress and a sharp rise in current density, significantly increasing the wear rate. On the other hand, intensified coupling vibrations lead to high-frequency oscillations, which, due to factors such as microcrack propagation and thermal stress effects, notably increase the wear rate. Furthermore, as the contact point approaches the groove position on the strip, a sudden increase in contact force and vibration occurs, further exacerbated by arcing discharge, resulting in a deterioration of dynamic interaction. Ultimately, the combined effects of frequency matching anomalies and dynamic interaction degradation destabilize the friction system, leading to the formation of an abnormal contact profile. This, in turn, increases both mechanical and electrical wear. If, during this period, there is a decrease in environmental humidity12, highly likely to be the “trigger” that triggers abnormal wear, or degradation in PCS structure and parameters, the resulting damage from mechanical and electrical wear is further intensified. Consequently, these processes feedback into the system, causing further deterioration of dynamic and wear performance, and leading to abnormal wear of the pantograph contact strip, characterized by increased wear rates and profile abnormalities, as shown in Fig. 26.

These findings effectively explain the sudden increase in wear rate and the abnormal contact strip wear profile observed in Figs. 1 and 2, which are provided from the perspectives of frequency matching, dynamic and performance. This analysis provides a robust foundation for preventing and mitigating abnormal wear in future applications.

Conclusions

In summary, this study investigates the causes of abnormal wear in the pantograph contact strip through a combination of simulation and experimental approaches. Initially, field tests were conducted to characterize the dynamic interaction of PCS, as well as to identify the contributing characteristic frequencies. Static modal tests on the pantograph and the cateanry were performed to facilitate frequency matching analysis. Subsequently, laboratory experiments were carried out to assess the effects of different current densities under operational conditions. A PCS dynamic simulation was then performed, taking into account the actual damage to the strip in the field. Finally, all of the aforementioned work was synthesized to provide a comprehensive analysis of the causes behind the abnormal wear profile and increased wear rate. The key conclusions are summarized as follows:

-

1.

The dynamic performance deteriorates after the strip experiences groove damage. When the groove depth exceeds 3 mm, the Fmax exceeds 300 N, and the offline arcing occurs. At a groove depth of 5 mm, the Fmax increases by more than three times.

-

2.

As the current density increases, the wear rate of the strip exhibits an exponential increase. Compared to the non-conductive state, the wear rate increased by a factor of 957.14, and under low-load current density conditions, it increased by 8.58 times. The increased arcing energy significantly enhances the adhesive effect at the contact surface, thereby exacerbating material transfer.

-

3.

The abnormal wear profile of the strip is primarily due to increased pantograph collector head vibration and higher current density near the 220 mm lateral stagger value, which causes an elevated wear rate in this section, leading to the initial formation of grooves. Further deterioration in dynamic interaction and an increase in arcing energy contribute to the deepening of the grooves.

-

4.

The abnormal wear rate of the strip is primarily due to the mismatch between the pantograph and catenary frequency (both static and dynamic), which induces localized resonance effects. When combined with the abnormal wear profile, this results in the deterioration of dynamic performance. Together, these factors cause instability in the friction system, leading to increased electrical and mechanical wear. The overall result is a significant degradation of both dynamic and wear performance, ultimately causing a sharp increase in wear rate, with a multiple-fold wear volume in sliding electrical contact process.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, W. Dynamics of Coupled Systems in High-Speed Railways. Elsevier (2020).

Accident involving a pantograph and the overhead line near litleport, Cambridgeshire 5 January 2012, Rail Accidents Report, Report 06/2013, November 2013.

Bucca, G. et al. Analysis of the failure of a tramcar pantograph component through combined experimental approaches. Eng. Fail. Anal. 141, 106725 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Hardening and prediction method for suspension system stiffness of pantograph head in electrified railway. J. China Railw. Soc. 44(6), 30–36 (2022).

Yi, C., Wang, D. & Zhou, L., et al. Evaluation of the influence of pantograph cracks on contact forces in the interaction between pantograph and catenary. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2375–2393 (2023).

Mei, G. et al. Study of load spectrum compilation method for the pantograph upper frame based on multi-body dynamics. Eng. Fail. Anal. 135, 106099 (2022).

Zhou, N. et al. Fatigue crack propagation model and life prediction for pantographs on high-speed trains under different service environments. Eng. Fail. Anal. 149, 107065 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Study on the influence of traction current phase on the off-line electromagnetic disturbance of pantograph-catenary at the time of pantograph-catenary separation. China Railw. Sci. 44(02), 151–158 (2023).

Gao, G. et al. Dynamics of pantograph-catenary arc during the pantograph lowering process. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 44(11), 2715–2723 (2016).

Zhou, N. et al. Friction and wear performance of pantograph-catenary system in electrified railways: state of the art. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 59(05), 990–1005 (2024).

Zou, D. et al. Status analysis and prevention-treatment technology study of abnormal wear of pantograph catenary system in urban rail transit. J. Mech. Eng. 59(10), 152–178 (2023).

Zhi, X. et al. Effect and behaviors of ambient humidity on the wear of metal-impregnated carbon strip in pantograph-catenary system. Tribol. Int. 188, 108864 (2023).

Bouchoucha, A., Chekroud, S. & Paulaier, D. Influence of the electrical sliding speed on friction and wear processes in an electrical contact copper stainless. Appl. Surf. Sci. 223, 330–342 (2004).

Lin X. Z., Zhu, M. H. & Mo, J. L., et al. Tribological and electric-arc behaviors of carbon/copper pair during sliding friction process with electric current applied. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 21(2) (2011).

Yang, H. J., Chen, G. X. & Gao, G., et al. Experimental research on the friction and wear properties of a contact strip of a pantograph- catenary system at the sliding speed of 350 km/h with electric current. Wear s332–333, 949–955 (2015).

Collina, A., Melzi, S. & Facchinetti, A. On the prediction of wear of contact wire in OHE lines: A proposed model. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 37(1), 579–592 (2002).

Bucca, G. & Collina, A. Electromechanical interaction between carbon-based pantograph strip and copper contact wire: A heuristic wear model. Tribol. Int. 92, 47–56 (2015).

Wei, X. K., Meng, H. F. & He, J. H., et al. Wear analysis and prediction of rigid catenary contact wire and pantograph strip for railway system. Wear 442–443 (2020).

Zhou, N., Zhi, X. S. & Cheng Y, et al. Contact strip of pantograph heuristic wear model and its application. Tribol. Int. 194 (2024).

Mishina, H. & Hase, A. Effect of the adhesion force on the equation of adhesive wear and the generation process of wear elements in adhesive wear of metals. Wear 432, 202936 (2019).

Ding, T. et al. Influence of the spring stiffness on friction and wear behaviours of stainless steel/copper impregnated metallized carbon couple with electrical current. Wear 267, 1080–1086 (2009).

Wang, J., Mei, G. & Lu, L. Analysis of the pantograph’s mass distribution affecting the contact quality in high-speed railway. Int. J. Rail Transp. 11(4), 529–551 (2023).

Wang, J. P., Ren, C. L. & Hong, L. The construction parameter optimization of high-speed pantograph. J. Phys. 2025(1) (2021).

Nåvik, P., Derosa, S. & Rønnquist, A. On the use of experimental modal analysis for system identification of a railway pantograph. Int. J. Rail Transp. 9(2), 132–143 (2021).

Zuo, X., Du, M. & Zhou, Y. Influence of contact parameters on the coupling temperature of copper-brass electrical contacts. Eng. Fail. Anal. 136, 106205 (2022).

Gao, G. et al. Magnetohydrodynamics modeling analysis of arc under lowering pantograph with load condition. High Volt. Eng. 45(12), 3916–3923 (2019).

Jin, M. et al. Experimental study on the transient disturbance characteristics and influence factors of pantograph-catenary discharge. Energies 15(16), 5959 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Influence of interface temperature on the electric contact characteristics of a C-Cu sliding system. Coatings 12(11), 1713 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Fretting wear behavior of brass/copper-graphite composites as a contactor material under electrical contact. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 184, 105703 (2020).

Wang, Q., Gao, G. & Ni, Z., et al. Influence of interface oxidation on the electrical contact properties of C-Cu contact pairs. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Applications (ICHVE). IEEE, 2022, 1–4.

Shen, M., Ji, D. & Hu, Q., et al. Current-carrying tribological behavior of C/Cu contact pairs in extreme temperature and humidity environments for railway catenary systems. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 1–12 (2024).

Ji, D. et al. The effect of temperature on the current-carrying tribological behaviour of C/Cu contact pairs in high humidity environments. Tribol. Lett. 72(2), 63 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Geometry deviation effects of railway catenaries on pantograph-catenary interaction: A case study in Norwegian Railway System. Railw. Eng. Sci. 29(4), 350–361 (2021).

Feng, Y. T. & Owen, D. A. 2D polygon/polygon contact model: Algorithmic aspects. Eng. Comput. 21(2/3/4), 265–277 (2004).

Lankarani, H. M. & Nikravesh, P. E. Continuous contact force models for impact analysis in multibody systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 5(2), 193–207 (1994).

Holm, R. Electric contacts: Theory and application. Springer Science & Business Media (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2469213), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFB4301201-03), the Independent Project of State Key Laboratory of Rail Transit Vehicle System (Grant No. 2023TPL-T05 and 2024RVL-T05).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2469213), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFB4301201-03), the Independent Project of State Key Laboratory of Rail Transit Vehicle System (Grant No. 2023TPL-T05 and 2024RVL-T05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xingshuai Zhi : Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. Ning Zhou : Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Haifei Wei : Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Hongming Chen : Data curation, Visualization. Yao Cheng : Funding acquisition, Investigation, Visualization. Yi Sun : Investigation, Formal analysis. Langtao Zhao : Investigation. Guanhua Huang : Investigation. Weihua Zhang : Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

According to the dynamic interaction verification standard EN50318, the simulation data is compared with actual measurement data from the rail line to validate the accuracy of the dynamic model. Table 2 presents a comparison between the measurement and simulation PCS contact force statistics from dynamic interaction tests on a subway line in Shenzhen and the simulation data, demonstrating compliance with the EN50318 standard (Figs. 27, 28).

Appendix 2

The dynamic equilibrium equation for the pantograph head is established as follows:

where F1 and F2 are the support reaction forces on the head springs, calculated as:Fig. R

Furthermore, the dynamic equilibrium equation for the head’s rotation is expressed as:

where f1 and f2 are the contact forces between the front and rear strips and the contact wire; θ is the rotation angle of the head about the balance arm; J is the equivalent moment of inertia of the head, which is a function of θ; and d is the distance between the front and rear strips.

The equivalent moment of inertia J is calculated as follows

where J01 and J02 are the moments of inertia of m1 and m2 about their respective centers of mass. As the influence of the mass on the moment of inertia is negligible during the head’s rotation, it is omitted from the calculation of J.

For the frame, which possesses only one independent rotational degree of freedom a, the dynamic equilibrium equation can be conveniently formulated, as shown in Eq. (13),

where fi(a) is a function of a.

The rigid-flexible coupled model of the pantograph accounts for the flexibility of specific components. The head strips are modeled as flexible bodies, while the remaining parts are treated as rigid. These bodies are connected via fixed joints to establish the coupled dynamic model. The contact region between the strips and the catenary is discretized using solid finite elements. The rest of the pantograph is modeled as rigid bodies, coupled with the flexible finite element body through fixed nodes.

The overall dynamic equilibrium equation of the pantograph can be written as,

where Mp is the mass matrix, Cp is the damping matrix, Kp is the stiffness matrix, u is the nodal displacement vector, and ff (t) is the load vector. For the parts modeled as rigid bodies, the dynamic equilibrium equations share the same form as those in the multi-body rigid pantograph model.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhi, X., Zhou, N., Wei, H. et al. Analysis of the abnormal wear of the pantograph contact strip through combined experimental and simulation approaches. Sci Rep 15, 45706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28380-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28380-0