Abstract

Zinc finger protein (ZNF) family is the largest transcription factor family in the human genome. Studies have shown that the aberrant expression of ZNF had a potential role in tumorigenesis. However, the role of ZNF family genes in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC) is still not systematically understood. Transcriptomic profiles and clinical data of endometrial carcinoma were obtained from TCGA and GEO databases. Based on differentially expressed ZNF genes, unsupervised clustering was employed to stratify samples into distinct subtypes, followed by enrichment analysis to compare gene expression patterns and pathway alterations across subgroups. Patients were subsequently divided into training and test cohorts, through univariate COX regression, LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) regression, and multivariate COX regression analyses, we identified prognostic ZNF genes in UCEC. A risk scoring model was established based on these prognostic ZNF genes, and its predictive performance was validated using extensive clinical data. The model was further evaluated for its associations with tumor microenvironment, immune infiltration, immunotherapy response, somatic mutations, and drug sensitivity. Additionally, single-cell RNA sequencing data and the human protein atlas (HPA) database were utilized to investigate the cellular-level functions and impacts of ZNF genes. We stratified UCEC patients into three subtypes based on differentially expressed ZNF genes, which exhibited distinct prognostic outcomes and pathway enrichment profiles. Eight prognostic ZNF genes were identified and incorporated into a ZNF scoring system named ZNF score to quantify patient risk. The ZNF score integrated with clinical characteristics demonstrated robust predictive performance in UCEC patients. Immune infiltration analysis demonstrated a significant increase in M1 Macrophages and M2 Macrophages abundance within the high-risk group. Drug sensitivity analysis identified potential therapeutic agents. Single-cell analysis, immunohistochemistry demonstrated and data-independent acquisition based quantitative proteomic analysis lower expression of most ZNF genes in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues, with predominant distribution in endothelial and epithelial cells. This study represents the first investigation utilizing ZNF genes to determine prognostic outcomes in UCEC patients. Our findings shed light on the potential of the ZNF score as a tool to evaluate ZNF expression patterns, immune cell infiltration, response to pharmacotherapy, clinicopathological features, and survival outcomes in UCEC. This may provide the more effective guide to select immunotherapeutic strategies of UCEC in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zinc finger protein (ZNF) family bind to sequence-specific DNA and is the largest binding protein family, encoded by 2% of human genes1. The ZNF domain is present in about 5% of human proteins and is associated with pathogenesis of many solid tumors2. Zinc finger motifs have different types, including Cys2His2 (C2H2) like, Gag knuckle, Treble clef, Zinc ribbon, Zn2/Cys6, TAZ2 domain like, Zinc binding loops and Metallothionein3. These domains could bind to DNA, RNA or proteins to function4. Increasing evidences had supported key roles for certain members of ZNFs in different cancers progression and stimuli. ZNF genes may contribute to cancer occurrence and progression, potentially functioning as oncogenes. ZNFs are involved in many fundamental cellular processes including transcription regulation, cell adhesion, protein degradation, DNA damage repair, chromatin remodeling, and more, consequently playing a critical role in human health and disease2,5,6. Emerging evidence has established significant associations between various ZNF family members and tumor biology across multiple malignancies, including but not limited to breast cancer7, pancreatic cancer8, colorectal9, gastric10, and esophageal cancers11, or lung adenocarcinomas12. ZNFs primarily function as transcription factors in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. The zinc finger protein 2 gene (ZIC2) mRNA expressions in CD4+ T cells are associated with the 5-year survival rate of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients13. Gaili An found that ZNF750 expression was significantly decreased in breast cancer patients and the patients with high expression of ZNF750 had a good prognosis14. According to Fan Xu, aberrant expressions of ZNF genes may represent potentially robust indicators for COAD patients’ prognosis and survival15.Epigenetic regulation of ZNF154 and ZNF132 may also have prognostic relevance for both HNSCC and LUAD patients16. Taken together, these studies indicate that ZNF genes may function as oncogenes involved in the occurrence and progression of cancer and may be a potential prognostic indicator and therapeutic target.

Endometrial carcinoma of the uterine corpus (UCEC) is among the most prevalent gynecologic malignancies, ranking second in incidence among female reproductive cancers in China (after cervical carcinoma)17,18. Globally, endometrial cancer affects over 287,000 women annually, making it both the most common gynecological cancer worldwide and the third most frequent malignancy in women from developed countries19. Key UCEC risk factors encompass reproductive factors (parity, late last birth, early menarche), metabolic disorders (obesity, type 2 diabetes), hormonal exposures (estrogen-only therapy, oral contraceptives), and lifestyle factors (aging, smoking)20. Early-stage endometrial cancer typically requires total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, while advanced cases necessitate surgery combined with systemic therapies including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy21,22. UCEC exhibits significant molecular and clinical heterogeneity, demonstrating distinct patterns of both locoregional recurrence and distant metastasis. Disease prognosis is critically dependent on histological classification and FIGO staging, factors that substantially complicate the establishment of standardized screening protocols and therapeutic approaches.

Therefore, the present study investigates the function of ZNF-related genes in UCEC using bioinformatics techniques. The ZNF score was developed that can be used as a prognostic tool and for investigation of immune-based treatments. We evaluated the prognostic model’s associations with immunological characteristics, immunotherapy efficacy, somatic mutations, and drug sensitivity. In summary, our prognostic model holds potential for identifying novel therapeutic targets and treatment strategies in endometrial carcinoma, thereby contributing to more precise anti-tumor interventions.

Methods

Data acquisition and processing

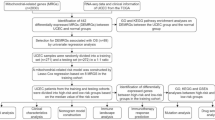

The cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) was used to extract RNA-Seq-derived gene expression profiles and clinical data from uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC) patients. Specifically, we obtained transcriptome profiling (RNA-Seq) data, Copy Number Variations (CNV) and clinical data from TCGA for 403 endometrioid adenocarcinoma patients, we excluded 4 samples with missing survival information, and the final remaining 399 samples were used for subsequent analyses in this study. To augment the clinical sample data, we used “endometrial carcinoma”, “Expression profiling by array” and “Homo sapiens” as keywords and searched for the required items in the public functional genomics database Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). We ultimately selected the GSE17025 series as our analytical dataset. For the GSE17025 microarray data, probe IDs were converted to official gene symbols using its platform annotation file (GPL570). In cases where multiple probes mapped to the same gene symbol, we retained the probe with the maximum variance across all samples for downstream analysis. All TCGA data, GEO data, mRNA expression data, and clinical details were downloaded using R software (version 4.4.2). To construct a comprehensive yet reliable starting set of zinc finger proteins, we retrieved a total of 1,787 ZNF protein genes from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB). This initial list was sourced exclusively from the reviewed Swiss-Prot section, filtered for Homo sapiens. The overall study design flowchart is illustrated in Figure S1.

Screening for differentially expressed ZNF genes

To identify significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between UCEC tumor samples and normal solid tissue samples, we utilized the “DESeq2” package for the TCGA-UCEC dataset and the “limma” package23 in R for the GSE17025 dataset. The DEGs were defined as genes with |log2FC|> 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. The expression profiles of differentially expressed ZNF genes (DE-ZNFs) were retrieved from both the TCGA-UCEC and GSE17025 datasets to facilitate subsequent comprehensive analyses.

Unsupervised clustering and consensus clustering analysis

Tumors exhibit significant molecular heterogeneity and can be classified into distinct subtypes based on their comprehensive omics profiles. To systematically evaluate the molecular heterogeneity of UCEC, we performed consensus clustering analysis using DE-ZNFs through the “ConsensusClusterPlus” R package (version 1.68.0)24. This analysis was conducted exclusively on the TCGA-UCEC samples (n = 399) to leverage its larger sample size and comprehensive clinical annotations for robust subtype identification and survival validation. The clustering procedure was iterated 1000 times to ensure the robustness and reproducibility of the subtype classification.

Functional enrichment analysis

DEGs between ZNF Clusters with significant survival differences after clustering were identified using the “limma” package. The screening thresholds were set at |log 2FC|≥ 1 and adj.p value ≤ 0.05. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) enrichment analyses were performed on the DEGs using “clusterProfiler” and “org.Hs.eg.db”25,26. The GO system consists of three components: biological process (BP), molecular functions (MF) and cellular components (CC). KEGG is a biological systems database that integrates genomic, chemical and systemic functional information. The enrichment results were visualized by using the “ggplot2” package.

Design and generation of ZNF gene score

Since the TCGA-UCEC cohort was the only dataset with available prognostic information, internal validation was performed. Patients diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma from the TCGA-UCEC cohort were randomly divided into a training set and a test set, with an equal allocation ratio of 1:1. This random split was performed on the single, complete TCGA-UCEC dataset to facilitate model development and subsequent internal validation. DE-ZNF genes with prognostic value were screened out by univariate Cox analysis of overall survival (OS). To minimize the risk of overfitting, a prognostic model was constructed using LASSO penalized Cox regression analysis. Variable selection and shrinkage of the prognostic model were achieved by running the LASSO algorithm in the “glmnet” R package27. The independent variables of the model were the DEGs with prognostic values, and the response variables were OS and status of patients in the training set. To improve the reliability and objectivity of the results, 1000 cross-validation runs were performed to determine the optimal value of the penalty parameter (λ). The normalized expression level of each gene and its corresponding regression coefficient were used to calculate the risk score of patients. The formula was established as follows:score = esum (each gene’s expression × corresponding coefficient). The patients were stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups according to the median value of the risk score. To evaluate the predictive power of the gene signature, a time-dependent ROC curve was built with the “survivalROC” R package.

Development the nomogram model

Clinicopathological parameters were extracted from the TCGA dataset, including age, grade and FIGO stage. The comprehensive clinical characteristics were integrated with the ZNF score to perform multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, enabling the development of a prognostic nomogram for individualized outcome prediction using the “rms” R package. In the complete TCGA-UCEC cohort, we assessed the 1-, 3-, and 5-year predictive accuracy of the nomogram by generating calibration curves to evaluate the model’s performance.

Correlation analysis of clinical characteristics and immune checkpoints

We performed a correlation analysis to further reveal the association between the ZNF score and some related clinical features, including (1) microsatellite status, such as MSS, MSI-L, and MSI-L; (2) tumor grade; (3) age; (4) immune-checkpoints such as CD274, TNFSF14, BTN3A1 and others; (5) human leukocyte antigen (HLA); (6) interleukin (IL); (7) Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB);

Analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells

We employed the CIBERSORT algorithm implemented in the IOBR package28 to quantify the infiltration levels of 22 distinct immune cell subtypes, complemented by ssGSEA (single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) to assess the activity scores of 13 immune-related functional pathways.

Estimation of stromal and immune scores

The ESTIMATE algorithm quantifies immune and stromal cell infiltration in tumors through transcriptomic analysis, generating Stromal, Immune, and combined ESTIMATE Scores, where elevated scores reflect increased non-malignant components in the tumor microenvironment (TME)29. The TIDE (Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion) algorithm evaluates tumor immune evasion potential through comprehensive analysis of gene expression signatures associated with T cell dysfunction and exclusion mechanisms, providing predictive insights into immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapeutic responses30. The Immunophenoscore (IPS) predicts immunotherapy response by analyzing immune-related gene expression patterns31. TIDE files were downloaded from the TIDE website (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) to calculate the TIDE score. The IPS of each UCEC sample was obtained from The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA, https://tcia.at/home) database.

Drug sensitivity prediction

The R package oncoPredict (https://github.com/OncoPredict/OncoPredict) was employed to predict the IC50 values of various anticancer drugs for each sample, and differences between the high- and low-risk groups were compared. A higher IC50 indicates lower sensitivity to the treatment.

Validation of ZNF gene based on proteomics analysis

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA; https://www.proteinatlas.org/) was used to analyze protein expression differences between UCEC and normal tissues. We obtained immunohistochemistry-based tissue section images for DEGs from both normal and tumor tissues through the HPA database.

Single-cell RNA dataset processing and analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from endometrial carcinoma and normal endometrial tissues were acquired from GEO datasets GSE173682 and GSE179640, respectively. The “Seurat” R package was employed for analysis. Rigorous quality control was performed by filtering out cells with the following criteria: detecting < 300 genes, detecting > 7,500 genes, total UMIs < 1,000, or mitochondrial gene ratio > 25%. Any cell expressing hemoglobin genes was also excluded. Genes expressed in ≤ 3 cells were removed. Data integration was then conducted using the anchor-based method in Seurat. After normalization, the top 2000 highly variable genes were identified. Dimensionality reduction was achieved using PCA (top 20 principal components) and UMAP. Cell type annotation was performed using the “SingleR” package with HumanPrimaryCellAtlasData as reference.

Tissue collection and processing

We collected endometrial tissue specimens from five patients diagnosed with endometrioid adenocarcinoma at the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between January and March 2025. All enrolled patients underwent hysterectomy procedures. Histopathologically confirmed tissue samples were systematically categorized into the EC (endometrial carcinoma) group, comprising macroscopic tumor tissues, and the PC (peri-tumoral control) group, consisting of histologically normal endometrial tissues obtained from a standardized 2-cm margin beyond the gross tumor boundary. All tissue specimens were selected based on histopathological evaluation performed by board-certified pathologists with ≥ 2 years of clinical experience. All specimens were collected from hysterectomy samples within an hour post-resection, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until data-independent acquisition (DIA)-based quantitative proteomic analysis. This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (No. KYLL-2025–160) and was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Result

Differential expression and analysis of ZNF genes in UCEC

To elucidate the expression profile of ZNF genes in UCEC, we systematically analyzed 1787 human ZNF protein-coding genes retrieved from the UniProt database. The expression patterns were comprehensively assessed using transcriptomic data from two independent cohorts: the TCGA dataset comprising 403 endometrioid adenocarcinoma patients and 19 normal controls, and the GSE17025 dataset containing 79 endometrioid carcinoma samples and 12 normal endometrial specimens. A total of 92 DE-ZNFs were identified (Fig. 1A,B), including 18 up-regulated ZNF genes and 74 down-regulated ZNF genes (Figure S2A-D).

Determination of zinc finger protein genes (ZNFs) and novel molecular subtypes in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC). (A) Venn diagram showing 92 differentially expressed zinc finger protein genes (DE-ZNFs) between TCGA-UCEC and GSE17025 datasets. (B) Heat map of 92 DE-ZNFs between UCEC and normal tissues in TCGA-UCEC. (C) The location of copy number variation (CNV) alteration of DE-ZNFs on 23 chromosomes. The deletion frequency, black dot; The amplification frequency, red dot. (D) Heatmap of consensus clustering matrix (k = 3) (E) Principal component analysis of the three patterns of DE-ZNFs expression, showing a remarkable difference on gene profiles between different patterns. ZNF cluster A, red; ZNF cluster B, blue; ZNF cluster C, green. (F) A complex heatmap revealing the relationships between clusters and other clinical features. (G) Survival difference among three ZNF expression patterns (P = 0.00052, Log-rank test). ZNF cluster A, yellow; ZNF cluster B, red; ZNF cluster C, blue. (H) KEGG-enriched pathways for the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between ZNF cluster B and C. (I) Enrichment of DEGs between ZNF cluster B and C in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF) in GO enrichment analysis.

To elucidate the association between CNVs of ZNFs and their transcriptional regulation, we performed a systematic analysis of CNV profiles. We demonstrated that CNV mutations were prevalent in the 92 DE-ZNFs. Specifically, ENPP2, ZFPM2, KLF10, PLAG1, and ZNF34 showed widespread amplifications, while CBFA2T3, KLF4, PYGO1, and UHRF1 showed prevalent deletions (Figure S2F). The locations of CNV alterations in the DE-ZNFs on the chromosomes are shown in (Fig. 1C). Genomic analysis showed these ZNF genes were absent on chromosomes 13, 14, 22, and Y but present on all other autosomes.

To further ascertain the influence of ZNF genes on UCEC, we Analysis of 399 endometrial carcinoma cases identified molecular subtypes with distinct ZNF gene expression patterns according to the expression of DE-ZNFs in the TCGA cohort. Three distinct expression patterns were identified using unsupervised clustering, meanwhile we obtained gene expression data and full clinical annotations for UCEC patients (Fig. 1D and Figure S2E). To validate the clustering efficacy, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, which demonstrated clear stratification of all endometrial carcinoma cases into three distinct molecular subgroups with minimal overlap, including 157 cases of pattern A, 83 cases of pattern B, and 159 cases of pattern C (Fig. 1E). The heatmap not only revealed clinical characteristics of the three ZNF clusters but also their correlation with ZNF gene expression. There were significant differences in ZNF transcriptional profiles among the three ZNF clusters (Fig. 1F). The ZNF gene expression levels in cluster B were significantly elevated compared to those in clusters A and C. We also found that the proportions of patients with higher stages and death outcomes were significantly higher in cluster B. Prognostic analysis of the three ZNF expression subtypes revealed that ZNF cluster C expressed more prominent survival advantage than cluster A and cluster B. Cluster B showed the worst survival advantage and the highest risk of death (Fig. 1G).

To investigate the biological basis for the survival differences among ZNF expression clusters, we conducted a comparative analysis of gene expression between clusters B and C. This differential gene expression analysis identified a set of DEGs, which were subsequently subjected to KEGG and GO enrichment analyses. These findings indicated that DEGs were involved in metabolism-related biological functions. The KEGG results were consistent with those of GO analysis, revealing significant pathway enrichments in “Proteoglycans in cancer”, “Regulation of actin cytoskeleton”, “Cytoskeleton in muscle cells”, “Human papillomavirus infection”, and “PI3K − Akt signaling pathway” (Fig. 1H). These pathways are also related to cellular signaling and metabolism. According to the BP, the DEGs played a significant role in the “Wnt signaling pathway”, “mitotic cell cycle phase transition”, “ossification”, and “mesenchyme development”. Within the realm of CC, “collagen − containing extracellular matrix”, “cell − substrate junction” and “spindle” were significantly abundant. Furthermore, MF analysis revealed a significant enrichment of DEGs in “D − binding transcription factor binding”, “actin binding”, and “protein serine/threonine kinase activity” (Fig. 1I). These findings suggest that DE-ZNFs may influence tumor progression through modulation of these pathways.

Development and validation of the ZNF genes signature

To enhance the clinical translational potential of our findings, we identified survival-associated DE-ZNFs and subsequently developed a robust risk prediction model using ZNF gene expression profiles.399 UCEC patients (entire set) were randomly allocated to the training set (n = 200) and test set (n = 199) by one-to-one ratio. Firstly, we employed univariate Cox regression analysis on the TCGA-UCEC set. 18 distinctly prognosis-associated genes were identified (Fig. 2A). Next, to prevent overfitting, we conducted 1000 LASSO regression iterations in the training cohort to ensure the attainment of the most robust and stable result (Fig. 2B,C). The sample scores can be determined through the regression coefficients obtained from the multivariate Cox regression analysis in the training cohort. A total of 8 significant ZNF genes (KPNA2, HIC1, NR3C1, TRIM36, BNC2, ZDHHC15, OTUD7A, and KRBOX1) filtered via LASSO and multivariate Cox regression, were significantly independently correlated with OS and prognostic value (Fig. 2C and Figure S3A). The formula mentioned in the methodology was applied by us to determine the risk score for each patient. We termed this the ZNF score. The counted risk scores of the patients were ranked from low to high and then the middle value was chosen as the threshold to label the patients as high or low risk, respectively.

Development of a prognostic signature for UCEC based on 8 ZNF prognostic genes. (A) Risk ratio forest plot shows that eighteen prognosis-related ZNFs, were significantly related to OS of UCEC patients. (B) Figure for LASSO coefficient spectrum of prognostic ZNF family genes. (C) Adjusted parameters of LASSO regression model. (D–F) Exhibition of predictive model based on risk score of the training, test, and entire sets, respectively. (G–I) Survival time and survival status between low-risk and high-risk groups in the training, test, and entire sets, respectively. (J–L) Time-dependent ROC curves of 1-, 3-, and 5-years of UCEC patients in training, test, and entire sets, respectively. (M–O) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of OS between low-risk and high-risk groups in the training, test, and entire sets, respectively.

Applying our established risk score model, we quantitatively assessed the prognostic risk scores across three distinct cohorts: the training set, test set, and the entire cohort. We contrasted the distribution of ZNF score (Fig. 2D–F), the survival status (Fig. 2G–I), the ROC curve (Fig. 2J–L), and the survival outcome (Fig. 2M–O) of UCEC patients between three groups of the training set, test set, and entire set, respectively. No significant differences were observed between those groups. The risk curves and scatter plots for the test, training and entire groups implied significantly higher mortality in high-risk patients compared to low-risk patients. ROC curves assessed the accuracy of this risk model in three sets. Time-dependent ROC analysis demonstrated that the ZNF score exhibited optimal predictive accuracy for 3-year and 5-year survival outcomes, with AUC values consistently exceeding 0.7. We deduced that this model is reliable and precise. Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that patients in the low ZNF score group demonstrated better OS than patients in the high ZNF score group in entire, training, and test sets. In summary, ZNF score could be used as an effective prognostic marker in UCEC.

Integration of ZNF signature and clinical characteristics for prognostic assessment

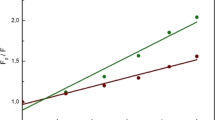

To enhance clinical translational utility, after asserting the prognostic reliability of the eight ZNF gene signature on UCEC outcomes, we used it along with patient clinicopathological data to construct a nomogram to forecast 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS (Fig. 3A). The calibration plot of the nomogram indicated optimal predictive accuracy, with a close overlap between predicted and actual survival rate (Fig. 3B). The nomogram demonstrated superior predictive accuracy compared to the ZNF score alone, significantly enhancing both the clinical applicability and therapeutic decision-making utility of our ZNF-based risk stratification system.

Nomogram and Correlation for ZNFs signature and clinical characteristics. (A) A nomogram for OS containing clinical characteristics including age, grade, stage, and ZNF score. (B) Calibration curves depicting the consistency between the predictions and observations. (C) The proportions of living and dead UCEC patients in the low and high ZNF score groups. Blue, living patients; red, deceased patients. (D) ZNF score based on survival status. (E) Relationships between MMP score and MSI. Blue, MSI-H group; red, MSI-L group; yellow, MSS group. (F) The proportions of patients with three clinical grades in the low and high ZNF score groups. Blue, grade 1 group; red, grade 2 group; yellow, grade 3 group. (G) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for high and low ZNF score patient groups in the patients with G3. (P = 0.015, Log-rank test). (H) Differences in the ZNF score among distinct grade clinical response groups. (I) The proportion of patient ages in the low or high ZNF score group. Blue, patients ≤ 65 years; red, patients > 65 years. (J) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for high and low ZNF score patient groups in patients > 65 years. (P < 0.001, Log-rank test). (K) Differences in the ZNF score based on age. MSS microsatellite-stable; MSI-L microsatellite instability-low, MSI-H microsatellite instability-high. (*, **, ***, **** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively).

Next, we used the ZNF score to systematically evaluate UCEC in terms of clinical characteristics including age, clinical stage, and status. Based on survival status, we investigated the difference in the distribution of survival status between patients with high and low ZNF scores. In the high ZNF score group, 82% of patients were alive and 18% were dead, and in the low ZNF score group, 94% of patients were alive and 6% were dead (Fig. 3C). It was showed patients who died had higher ZNF score than those who survived (Fig. 3D). In addition, we analyzed the correlation between MSI and ZNF score, found that patients in the low ZNF score group had a higher proportion of MSS and lower proportion of MSI-H (Fig. 3E). We observed an elevated proportion of patients with an advanced clinical grade in the high ZNF score group (Fig. 3F). To further assess the prognostic value of the ZNF score in the different clinical grades, we performed Kaplan–Meier analyses. We found that the ZNF score exhibited prognostic power in various clinical grades. Those with G3 disease, the low ZNF score group had a better prognosis than the high ZNF score group (Fig. 3G). Patients with G1 or G2 grade had lower ZNF score than those with G3 grade (Fig. 3H). These findings suggest a potential oncogenic role of ZNF genes in promoting tumor progression and high-grade transformation in endometrial carcinoma. Furthermore, age-stratified analysis revealed significant differences in ZNF risk scores between younger (< 65 years) and older (≥ 65 years) patient cohorts, suggesting potential age-related variations in ZNF expression patterns. The high ZNF score group demonstrated a significantly higher proportion of elderly patients (age > 65 years) compared to the low ZNF score group (Fig. 3I). Younger patients had significantly lower ZNF scores (Fig. 3K), notably, even in the elderly patient cohort (age ≥ 65 years), individuals with lower ZNF risk scores demonstrated a significant survival advantage compared to their high-score counterparts, suggesting the robust prognostic value of ZNF signatures across age strata (Fig. 3J). Alluvial diagram visualizing individual UCEC patient attribute dynamics. The analysis revealed strong associations between ZNF cluster B, high ZNF scores, grade 3 tumors, advanced age, microsatellite stability, and mortality (Figure S3B-E). These results demonstrate that ZNF score has the potential to act as a biomarker for assessing clinical characteristics and predicting prognosis in patients with UCEC.

Association between ZNF score and immune infiltration

The immune infiltrating microenvironment plays a pivotal role in modulating tumor progression, therapeutic response, and patient prognosis by orchestrating complex interactions between immune cells and the tumor milieu. To systematically investigate the immune microenvironment characteristics associated with ZNF risk scores, we performed Spearman correlation analysis between ZNF scores and TME immune cell infiltration patterns. The analysis revealed significant immune cell heterogeneity, with distinct correlation patterns illustrated in (Fig. 4A). Notably, tumors with elevated ZNF scores demonstrated significantly enhanced immune infiltration, showing strong positive correlations with activated dendritic cells, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, follicular helper T cells, and resting memory CD4 + T cells (Fig. 4B,C and Figure S4A-D).

Correlation between immune infiltration and the ZNF score. (A) Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between the ZNF score and immune cell infiltration in the TCGA UCEC cohort. Red, positive correlation; blue, negative correlation. (B) Correlation with T cells regulatory Tregs. (C) Correlation with Macrophages M2. (D) Correlation between the ZNF score and immune checkpoints. (E) Correlation with TNFRSF4. (F) Correlation with TNFRSF14. (G) Correlation between the ZNF score and HLA. (H) Correlation with HLA-A. (I) Correlation with HLA-DMA. (J) Correlation between the ZNF score and interleukins. (K) Correlation with IL32. (L) Correlation with IL15. HLA human leukocyte antigens. (*, **, *** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, respectively).

Upon investigation of the correlation between the ZNF score and immune checkpoints related-molecules, we found that the ZNF score showed a significant positive correlation with immune checkpoints (Fig. 4D). Among them, TNFRSF4 and TNFRSF14 showed significant positive correlation (Fig. 4E,F). Most immune checkpoints, such as CD47, TNFSF14, CD274 and so on, were significantly different. (Figure S4E-L and Figure S5A-D). In addition, we found that different types of HLA were negatively correlated with the ZNF score (Fig. 4G), HLA-DMA and HLA-A being the most prominent (Fig. 4H,I and Figure S5E-J). This suggests that ZNF score correlate with many immune checkpoints and HLA molecules. We assessed the expression correlation between the ZNF score and interleukins (Fig. 4J), the strongest correlation were identified: IL32 and IL15 (Fig. 4K,L, and Figure S5K-L). These findings collectively demonstrate that ZNF expression may influences immune regulation in UCEC.

Tumor microenvironment composition and gene mutation analysis based on ZNF score

To elucidate the impact of ZNF risk scores on TME composition, we systematically analyzed the correlation between ZNF score group and infiltration levels of 22 distinct immune cell subtypes in UCEC. ZNF score and infiltration levels of the 3 observed immune cell types were negatively correlated significantly, such as Mast cells resting, NK cells activated, and T cells regulatory Tregs (Fig. 5A). However, there was a positive correlation in Macrophages M1, Macrophages M2, T cells memory activated, and T cells follicular helper. On immune function analysis, the low-risk group showed higher scores for CCR, check-point, HLA, T cell co-stimulation and type II IFN responses (Fig. 5B). This result further indicated that our ZNF score was implicated in the TME of UCEC. As shown in the heatmap, the high ZNF rating group was significantly enriched in multiple immune cells (Fig. 5C).

Comparisons of immune and mutation landscape between the two ZNF risk groups. (A)The differences in 22 types of immune cell infiltration in the EC tumor microenvironment between high and low ZNF score groups using the CIBERSORT algorithm. (B) ssGESA analysis of differences 13 immune-related functions in tumor microenvironment between high and low ZNF score groups. (C) A complex heatmap revealing the activation states of immune functions and immune cells in distinct ZNF score groups, and the tumor purity, ESTIMATE score, immune score, and stromal score were used as patient annotations. Red, activated state; blue, inhibition state. (D–G) The violin plot shows the difference in the ESTIMATE score, immune score, stromal score and the tumor purity between the low and high ZNF score groups. (H) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) of patients with two TMB clusters. The numbers of patients in low and high TMB groups were 217 and 161, respectively (P = 0.012, Log-rank test). (I) Survival analyses of patients with both ZNF score and TMB using Kaplan–Meier curves. H, high; L, Low; TMB (tumor mutation burden) (P < 0.001, Log-rank test). (J–K) The waterfall plot of genetic alterations in patients with high and low ZNF score groups. Each column represents individual patients. The upper barplot shows the TMB, while the number on the right indicates the mutation frequency in each gene. The right barplot shows the proportion of each variant type. TMB tumor mutational burden. (*, **, ***, **** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively).

To investigate the relationship between ZNF score and TME composition, we performed comprehensive ESTIMATE (Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data) analysis, including immune scores, stromal scores, and tumor purity assessment. These analyses revealed significant differences in TME characteristics between ZNF score groups, with corresponding survival disparities (Fig. 5D–G). The Violin plot shows that ESTIMATE, immune, and stromal scores were higher in the low-score group than in the high-score group, whereas tumor purity was lower in the low-score group. Therefore, compared with UCEC patients with a high ZNF score, those with a low ZNF score had tumors with more abundant immune and stromal components, and therefore had stronger immune function and better prognosis.

To more comprehensively characterize the ZNF signature profile, we also verified the correlation between the TMB and the ZNF score, which showed a positive relationship. We divided the patients with UCEC into two categories: L-TMB and H-TMB. Kaplan–Meier curves revealed that the H-TMB had the longer survival (Fig. 5H). Next, we evaluated the survival among UCEC patients with TMB and ZNF score. Based on previous results, we believed that patients with low ZNF and high TMB score have the most significant survival advantage (Fig. 5I). We then compared the top 30 genes with the highest frequency of somatic mutations between groups with high and low ZNF scores in the TCGA cohort (Fig. 5J,K). Somatic mutation analysis revealed distinct mutation patterns between risk groups, with the high-risk cohort showing lower mutation frequencies in key driver genes compared to the low-risk group: PTEN (78% vs. 85%), ARID1A (51% vs. 60%), and PIK3CA (50% vs. 52%). Meanwhile, we also analyzed the somatic mutation distribution of 8 ZNF prognostic genes between the high and low ZNF score groups (Figure S6A-B). Our results showed that BNC2 exhibited the highest frequency of mutations in both the high-risk and low-risk groups, no mutations were detected in KRBOX1 genes at the same time. These mutated genes deserve further study.

The role of the ZNF score in predicting immunotherapeutic benefits

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) such as programmed death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) has become one of the most promising approaches in the field of cancer therapy. IPS analysis suggests enhanced responsiveness to CTLA4-targeted immune checkpoint blockade in low-risk patients (Fig. 6A), ZNF score shows potential for guiding personalized immunotherapy in UCEC. To verify how the ZNF score relates to responses to anticancer drugs, we used TIDE to predict the therapeutic effect of ICI based on pretreatment tumor profiles.We combined ZNF score with multiple TIDE scores to conduct correlation analysis, control analysis and survival analysis. We found that the TIDE score was also associated with prognosis; patients with the high TIDE score had a distinctly better prognosis than the low score group (Fig. 6B). Survival analysis based on both TIDE and ZNF score showed that patients with high TIDE and high ZNF score had the worst prognosis, whereas patients with low ZNF and low TIDE score had the best prognosis (Fig. 6C). We took the same approach to analyze targeted carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAF), CD274 and immune dysfunction. There was prominent negative correlation between ZNF score and immune dysfunction (Fig. 6D,E), which patients with high immune dysfunction had more significant prognostic advantage than the low (Fig. 6F). Survival analysis combining immune dysfunction with the ZNF score showed that patients with a low ZNF score and high immune dysfunction had the best survival (Fig. 6G). Patients with high ZNF score were more likely to express CD274 (Fig. 6H,I). Survival analysis combining CD274 with the ZNF score showed that patients with a low ZNF score and high CD274 had the best survival (Fig. 6J). Furthermore, low ZNF score correlated with increased CAF levels (Fig. 6K). Combined analysis revealed poorest survival in patients with high ZNF scores and low CAF (Fig. 6L). Thus, integrating ZNF score with TIDE, immune dysfunction, CAF, and CD274 expression enhances ICB treatment prediction accuracy, enabling more precise patient stratification and improved diagnostic performance.

Immune microenvironment evaluation between the low and high ZNF score groups. (A) The comparison of immunophenoscoring (IPS) scores. (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS of patients. The numbers of patients in low and high TIDE groups were 345 and 54, respectively (P = 0.0044, Log-rank test). (C) Survival analyses of patients with both ZNF score and TIDE using Kaplan–Meier curves. (P < 0.0001, Log-rank test). (D) The relative distribution of dysfunction score was compared between the low and high ZNF score groups. (E) The correlations between dysfunction and ZNF score in three ZNF clusters. (F) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS of patients. The numbers of patients in the low- and high-immune dysfunction groups were 268 and 131, respectively (P = 0.0085, Log-rank test). (G) Survival analyses of patients with both ZNF score and immune dysfunction using Kaplan–Meier curves. (P = 0.00029, Log-rank test). (H) The relative distribution of CD274 was compared between the low and high ZNF score groups. (I) The correlations between CD274 and ZNF score in three clusters. (J) Survival analyses stratified by both the ZNF score and CD274 using Kaplan–Meier curves. (P < 0.001, Log-rank test). (K) The relative distribution of CAF was compared between the low and high ZNF score groups. (L) Survival analyses stratified by both the ZNF score and CAF using Kaplan–Meier curves. (P < 0.0001, Log-rank test). TIDE tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion, CAF cancer-associated fibroblast. (*, **, ***, **** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively).

Drug sensitivity analysis

We conducted drug sensitivity analysis on 198 compounds from the GDSC database, comparing IC50 values between different ZNF groups (Fig. 7A–H) and evaluating their correlation with ZNF scores (Fig. 7I–P). Identified therapeutic agents with different ZNF groups: (1) Foretinib, Palbociclib, Selumetinib, and Trametinib showed increasing IC50 values with higher risk scores; (2) Bortezomib, Ibrutinib, Savolitinib, and Sepantronium bromide demonstrated decreasing IC50 values with elevated risk scores. These findings suggest potential therapeutic strategies: high-risk patients may benefit from Bortezomib, Ibrutinib, Savolitinib, and Sepantronium bromide, while low-risk patients show better responses to Foretinib, Palbociclib, Selumetinib, and Trametinib, providing valuable guidance for personalized treatment in UCEC.

Drug sensitivity analysis of high and low ZNF score groups in TCGA-UCEC cohort. (A–H) Differences in the IC50 of anti-tumor drugs between different ZNF score groups. (A) Foretinib, (B) Palbociclib, (C) Selumetinib, (D) Trametinib, (E) Bortezomib, (F) Ibrutinib, (G) Savolitinib, (H) Sepantronium bromide. (I–P) Correlation between anti-tumor drugs and ZNF score. (I)Foretinib, (J) Palbociclib, (K) Selumetinib, (L) Trametinib, (M) Bortezomib, (N) Ibrutinib, (O) Savolitinib, (P) Sepantronium bromide. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration. (*, **, ***, **** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively.)

Immunohistochemical analysis of prognostic ZNF genes

We used immunohistochemical staining data from the HPA database to investigate the differences in expression of eight ZNF prognostic gene-related proteins in normal and endometrial carcinoma tissues. Results as shown in the Figure S7, KPNA2 had a higher expression in endometrial carcinoma tissue, HIC1, NR3C1, BNC2, ZDHHC15, expression in endometrial carcinoma tissue is reduced, further emphasize its correlation with the potential of endometrial carcinoma, confirmed the prognostic value of the ZNF gene in endometrial cancer. Regrettably, TRIM36, OTUD7A and KRBOX1 immunohistochemical data were unavailable in the HPA database. These findings underscored the importance of ZNF genes in the pathogenesis of UCEC, creating the way for potential therapeutic strategies targeting these critical regulatory molecules.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing data analysis

A total of 35,678 endometrial carcinoma cells and 16,938 normal endometrial cells were obtained from scRNA-seq datasets GSE173682 and GSE179640, respectively.Cell clusters were annotated into distinct cell types using UMAP algorithm combined with the “SingleR” package and CellMarker database.Normal endometrial samples were classified into eight distinct cell types: epithelial cells, fibroblasts, T cells, monocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and B cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast, endometrial carcinoma datasets were categorized into ten cell populations: fibroblasts, T cells, smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, tissue stem cells, NK cells, and B cells (Fig. 8B). The bubble map shows the expression of ZNF prognostic genes for each cell type in both normal (Fig. 8C) and tumor samples (Fig. 8D). Meanwhile, Scatter plots show the expression of those genes in different cell types (Fig. 8E–H). The data revealed decreased HIC1 expression in smooth muscle cells of tumor tissues, KPNA2 showed significant upregulation across all cell types in tumor tissues, while NR3C1 expression was consistently lower in tumor tissue cells compared to normal tissues.

scRNA-seq of normal endometrial tissues and UCEC. UMAP representations of eight distinct cell types in normal tissues (A) and ten distinct cell types in UCEC (B), processed through filtration, normalization, and analysis with the “Seurat” package. (C,D) The bubble map shows differences in the expression of ZNF genes between normal tissues (C) and UCEC (D), utilizing the “SingeR” package for annotation. The size of the dots represents the percentage of cells expressing the gene. The color of the dots represents the average expression level; purple indicates high expression, whereas yellow, indicates low expression. (E–H) Expression levels of ZNF prognostic genes in normal tissues and UCEC. (E) BNC2, (F) HIC1, (G) KPNA2, (H) NR3C1.

Data-independent acquisition (DIA)-based quantitative proteomic analysis

To validate the expression of ZNF prognostic genes in endometrial carcinoma, we collected matched tumor and peri-tumoral tissues from five patients for DIA-based quantitative proteomic analysis. Our analysis revealed distinct protein signatures between tumor and peri-tumoral tissues for five ZNF-related proteins (Fig. 9A–E). Paired boxplot analysis demonstrated that TRIM36 and KPNA2 showed elevated expression in tumor tissues, whereas HIC1, NR3C1, and BNC2 exhibited decreased expression compared to peri-tumoral controls—findings consistent with immunohistochemical results from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database. These results reinforce the potential relevance of these markers in endometrial carcinoma and confirm the prognostic value of ZNF genes. However, proteomic data were unavailable for ZDHHC15, OTUD7A, and KRBOX1. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of ZNF genes in UCEC pathogenesis and suggest potential therapeutic avenues targeting these key regulatory molecules.

Discussion

Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma (UCEC) represents a gynecological malignancy of growing prevalence, characterized by a consistent rise in both incidence and mortality rates. Projections indicate that its incidence will escalate to 33 cases per 100,000 individuals within the next decade32. The negative relationship between the incidence and mortality of UCEC and economic indicators reflects, to a certain extent, the greater difficulty for women in underdeveloped regions to be diagnosed through evidence-based medicine compared with women in developed regions18.

Zinc finger proteins, which constitute the largest transcription factor family with finger-like DNA binding domains, play a significant role in multiple biological processes. However, the influence for the ZNF-relate genes has not been studied on UCEC diagnosis and prognosis, and the mechanism underlying the role of ZNFs in UCEC warrants further investigation. Advances in bioinformatics and sequencing technologies have facilitated the development of multiple immune-related prognostic signatures, particularly for evaluating individual prognosis in endometrial carcinoma33,34,35. Therefore, Bioinformatics-based exploration of the association between endometrial carcinoma and zinc finger protein genes facilitates more precise anti-tumor therapies, offering significant clinical implications for improving patient prognosis.

In this study, we analysed the clinical information and transcriptome data of UCEC patients from TCGA. According to differential expression of ZNF gene, we identified three distinct ZNF expression patterns which displayed differences in Pathway enrichment and disease prognosis. To quantify the ZNF expression pattern in individual UCEC patients, we established a scoring system based on the expression of ZNF Prognostic gene including KPNA2, HIC1, NR3C1, TRIM36, BNC2, ZDHHC15, OTUD7A and KRBOX1. UCEC patients were divided into high and low risk groups based on the median ZNF score. The high-risk patients exhibited a poorer survival status than those in the low-risk category. Our ZNF score effectively predicted the long-term outcomes for UCEC patients, as per the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and the AUC values higher than 0.62 at 1, 3, and 5 years. Subsequently, a nomogram was developed by integrating various clinical variables with the ZNF score, providing a comprehensive perspective on the prognostic capability. This approach offers a promising prognostic modeling methodology and suggests novel avenues for therapeutic strategies in UCEC.

Cancer development involves complex interactions between tumor cells, microenvironment components, and immune responses. TME, comprising malignant, immune, and stromal cells, critically influences tumor progression and therapy response. Chronic inflammation recruits immune cells, particularly macrophages and lymphocytes, creating an immunosuppressive milieu that supports tumor growth36. These immune components play pivotal roles in tumor initiation, progression, metastatic dissemination, and therapeutic responsiveness. Generally, a more pronounced tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes indicates a better immune reaction that may eliminate cancer cells, and is usually associated with better prognosis and survival37. Immune profiling revealed significantly elevated infiltration of both M1 and M2 macrophage subtypes in high ZNF score UCEC patients. These monocyte-derived immune cells exhibit distinct functional polarization, with accumulating evidence implicating M2 macrophages as crucial mediators of UCEC progression through their role in establishing an immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment38. In vitro co-culture experiments demonstrated that M2-polarized macrophages markedly reduced UCEC cell radiosensitivity through exosome-mediated intercellular communication39. Our study revealed significant M2 macrophage infiltration in high ZNF score UCEC patients with poor prognosis. Additionally, high ZNF score individuals showed marked upregulation of immune checkpoints, which mediate immunosuppressive signaling and promote tumor immune evasion.

Furthermore, most studies have focused on a single TME cell type or single protease, but the overall TME infiltration characteristics mediated by the combined effects of multiple ZNF genes have not been comprehensively recognized. Low ZNF scores had a better prognosis, along with more abundant immune cell infiltration and stronger antitumour immunity. Our work indicated that ZNF score could be a potential tool to evaluate ZNF expression patterns, immune cell infiltration, response to pharmacotherapy, clinicopathological features, and survival outcomes in UCEC, and has the potential to provide novel areas for the study of epigenetics in UCEC. Our seminal exploration of the role of the overall ZNF expression pattern in the infiltration of TME cells will contribute to a deeper understanding of the mechanism of the TME antitumour immune response and a more effective strategy for guiding immunotherapy.

We used the TIDE score for predicting immune escape in UCEC patients during immunotherapy. The chance of tumor immune escape during immunotherapy increases with higher TIDE scores. While no significant difference in TIDE scores was observed between high- and low-risk groups, high-risk patients with elevated TIDE scores demonstrated poorer prognosis. Therefore, we may need to pay corresponding attention to the immunotherapy of high-risk patients.

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) predicts immunotherapy efficacy in diverse malignancies, representing both DNA repair impairment and enhanced neoantigen production40. We analyzed somatic mutation information to determine the TMB for each patient with UCEC and found disparities between the two groups, with the PTEN gene having the highest rate of mutation. The PTEN protein acts as a phosphatase, antagonizing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway41,42. This pathway is crucial for cell survival, growth, and proliferation. According to our analysis, PTEN mutations are significantly higher in the low-risk patients than those in the high-risk category, and patients with low TMB have a poorer prognosis than those with high TMB. This may indicate that PTEN is a more noteworthy target for prognosis. Mechanistic analyses demonstrated that ARID1A deficiency promoted PU.1-dependent HDAC7 transcription, whose overexpression decreased ENO1 acetylation to drive HCC cell proliferation43. In endometrial cancer, mutations of PTEN and PIK3CA can occur simultaneously and may appear in the same tumor, potentially generating a synergistic effect44. Additionally, the TMB exhibited good discriminatory ability among patients with UCEC, regardless of whether it was used as a standalone prognostic factor or analyzed in combination with the risk score. Combining TMB with the risk score enhances prognostic accuracy, indicating potential clinical value.

Drug sensitivity analysis indicated differential sensitivity for many therapeutic agents in different risk groups, Drug sensitivity analysis predicted therapeutic agents with differential efficacy across risk groups, these findings require extensive clinical validation. Therefore, we may need to increase focus on these drugs in the treatment of UCEC. Overall, these findings point to the feasibility of our model in predicting both the prognosis and the immunotherapy response of patients with UCEC, which may help to guide clinical decision-making.

Our data-independent acquisition (DIA) quantitative proteomics analysis identified significant differential expression of five key proteins—BNC2, HIC1, KPNA2, NR3C1, and TRIM36 between tumor tissues and matched adjacent normal controls. BNC2 acts as a key regulator of specific collagens, matrix metalloproteases, and other matrisome-related components in both breast cancer cells and fibroblasts—the primary cell types responsible for the synthesis and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the tumor microenvironment. Through this regulatory role, BNC2 influences the migratory and invasive behavior of cancer cells45. It has been identified as a novel transcriptional modulator of ECM and cytokine-associated genes in fibroblasts. In addition, multiple studies have reported associations between BNC2-related single nucleotide polymorphisms and susceptibility to various malignancies, including prostate46, bladder47, skin48, and endometrial cancer49,50. In the esophagus, BNC2 functions as a tumor suppressor, with its deletion frequently observed during the progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma51. Furthermore, work by Yali Wu et al. revealed that both BNC1 and BNC2 are downregulated in HCC, suggesting their potential involvement in hepatocarcinogenesis52. HIC1 located on chromosome 17p13.3, is involved in a wide range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, metastasis, and motility53. It is well established that HIC1 encodes a tumor suppressor that is frequently epigenetically silenced in multiple human cancers, such as pancreatic, breast, prostate, and renal cell carcinomas, as well as laryngeal cancer53,54. In gastric cancer, HIC1 may suppress tumor progression by maintaining normal cellular metabolism and inhibiting mTOR signaling pathway activation55. Data from Xiaoguang Zhou et al. demonstrated for the first time that HIC1 inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion in bladder cancer through the YAP signaling pathway56. Furthermore, reduced expression of miR-149-3p target genes, including HIC1, has been linked to poor overall survival in UCEC57. KPNA2, a member of the Karyopherin α nuclear transport receptor family, facilitates the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of proteins containing specific basic amino acid motifs. Mechanistically, KPNA2 acts as a critical nuclear import chaperone for the transcription factor CREB3L1, orchestrating tumor microenvironment remodeling that drives progression and metastasis in differentiated thyroid carcinoma58. KPNA2 is frequently overexpressed in various malignancies, where it correlates with poor prognosis. This protein promotes tumorigenesis and disease progression by participating in key processes such as cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, immune response, and viral infection. Notably, a truncated isoform of KPNA2 has been shown to impair the nuclear import of p53, resulting in its cytoplasmic accumulation and subsequent upregulation of genes that promote proliferation59,60,61. Elevated KPNA2 expression is closely associated with advanced tumor stage, progression, and metastasis across multiple cancer types, establishing it as a potential prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer62, breast cancer63, epithelial ovarian carcinoma64 and gastric cancer65. Supporting this, data from Kristain Ikenberg et al. demonstrate that KPNA2 is significantly upregulated in human endometrial carcinomas, where it correlates with higher tumor grade, advanced FIGO stage, p53 overexpression, PI3K/AKT pathway activation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition66. NR3C1, which encodes the glucocorticoid receptor, is a single-copy gene in the human genome. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma, genetic knockdown of NR3C1 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and activates the ATF6-PINK1/BNIP3-mediated mitophagy pathway, ultimately suppressing cancer cell proliferation and migration67. In UCEC, differential expression analysis revealed that NR3C1 is expressed at lower levels than in normal endometrial tissue. Univariate Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier survival analyses demonstrated that reduced NR3C1 expression is significantly associated with shorter survival time in UCEC patients68. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis of UCEC patient cohorts identified clinical Stage III, Stage IV, advanced age, and low NR3C1 expression as independent prognostic factors for poor clinical outcomes69. TRIM36 possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and has been implicated in tumor suppression. In vitro studies demonstrate that it directly ubiquitinates cyclin E, thereby facilitating its proteasomal degradation and suppressing hepatocellular carcinoma progression70. Supporting its role as a tumor suppressor, data from Bin Zhao et al. reveal that TRIM36 effectively inhibits the tumorigenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by repressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway71. Jianxin Wang et al. identified ZDHHC15 as a novel upstream inhibitor of the Hippo signaling pathway and demonstrated that it operates within a positive feedback loop to sustain YAP activity. Their findings provide compelling evidence that ZDHHC15 expression is critical for dietary palmitic acid (PA)-promoted metastasis in breast and ovarian cancer models72. Correspondingly, ZDHHC15 is significantly upregulated in glioma, where its expression positively correlates with advanced malignant phenotypes73. OTUD7A has been characterized as a tumor suppressor in HCC. It directly interacts with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and cleaves its polyubiquitin chains, thereby inhibiting the NF-κB signaling cascade and suppressing the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells. In human HCC tissues, OTUD7A expression is inversely correlated with that of its upstream transcriptional repressor, Snail1, which binds to the OTUD7A promoter to suppress its transcription74. To date, Snail1 is the only upstream regulator known to control OTUD7A, while TRAF6 represents its major downstream effector; this axis exerts a tumor-suppressive function exclusively in HCC. The role of OTUD7A in other malignancies remains unexplored. There are currently no published studies on the role of KRBOX1 in malignant tumors.

Building on our findings, future work will focus on validating and extending the ZNF signature through the following key directions: (1) Independent Clinical Validation: Applying the ZNF scoring model to an independent UCEC cohort to verify its prognostic value. In the interim, we will validate its association with the tumor microenvironment by comparing immune cell infiltration (e.g., via flow cytometry) and immune checkpoint expression between high and low ZNF score groups. (2) Mechanistic Elucidation: Performing in vitro and in vivo functional studies to delineate the roles of key ZNFs in UCEC pathogenesis, with a focus on their impact on core pathways such as Hippo/YAP and Wnt/β-catenin, and their interaction with the tumor microenvironment. (3) Translational Exploration: Assessing the model’s therapeutic predictive power by evaluating the drug sensitivity of patient-derived cells with different ZNF scores to selected therapeutic agents, thereby bridging the gap between the computational model and clinical application.

Our study has several limitations. First, all analyses were conducted using data from the TCGA database, and the scarcity of additional comprehensive clinical datasets limited further subgroup analyses. The lack of an independent external cohort for validation may also introduce bias. Second, the inherent technological differences between RNA-Seq (TCGA) and microarray (GSE17025) platforms, particularly the predefined probe set of the latter, mean that our 92-gene signature represents a high-confidence core set of ZNFs, rather than a comprehensive atlas. Future studies with larger RNA-Seq cohorts will be valuable to expand upon this core signature and uncover the full spectrum of ZNF involvement in UCEC. Third, the proteomic analysis had a relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the observed ZNF expression patterns. Despite these limitations, our study establishes a foundational ZNF-based prognostic framework for UCEC. Looking forward, the priority will be to address these gaps through independent clinical validation, mechanistic functional studies, expansion of the ZNF signature using larger homogeneous RNA-Seq cohorts, and assessments of therapeutic predictability, as outlined in our future directions. These concerted efforts are crucial to translate our computational findings into clinically actionable insights.

Conclusions

We developed a prognostic model for UCEC based on eight ZNF genes, which effectively stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes. Our findings suggest that these ZNF genes may play a significant role in UCEC and have the potential to be developed into clinical biomarkers in the future. However, their translation into routine practice requires further mechanistic investigation and preclinical validation.

Data availability

The data during the current study are available from TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database, UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/), and The Human Protein Atlas (HPA; https://www.proteinatlas.org/). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Vaquerizas, J. M., Kummerfeld, S. K., Teichmann, S. A. & Luscombe, N. M. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2538 (2009).

Kamaliyan, Z. & Clarke, T. L. Zinc finger proteins: guardians of genome stability. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 1448789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1448789 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Structures and biological functions of zinc finger proteins and their roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark Res. 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-021-00345-1 (2022).

Ecco, G., Imbeault, M. & Trono, D. KRAB zinc finger proteins. Development 144, 2719–2729. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.132605 (2017).

Gamsjaeger, R., Liew, C. K., Loughlin, F. E., Crossley, M. & Mackay, J. P. Sticky fingers: zinc-fingers as protein-recognition motifs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2006.12.007 (2007).

Singh, J. K. & van Attikum, H. DNA double-strand break repair: Putting zinc fingers on the sore spot. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 113, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.09.003 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Clinical Significance of ZNF711 in human breast cancer. Onco. Targ. Ther. 13, 6593–6601. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S251702 (2020).

Somerville, T. D. D. et al. ZBED2 is an antagonist of interferon regulatory factor 1 and modifies cell identity in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11471–11482. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921484117 (2020).

Pu, W. et al. Targeted bisulfite sequencing reveals DNA methylation changes in zinc finger family genes associated with KRAS mutated colorectal cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 759813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.759813 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Zinc finger protein CTCF regulates extracellular matrix (ECM)-related gene expression associated with the wnt signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 625633. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.625633 (2020).

Hong, K. et al. Comprehensive analysis of ZNF family genes in prognosis, immunity, and treatment of esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer 23, 301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10779-5 (2023).

Zhu, Q. et al. Methylation-driven genes PMPCAP1, SOWAHC and ZNF454 as potential prognostic biomarkers in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 21, 1285–1295. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2020.10933 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Correlation of zinc finger protein 2, a prognostic biomarker, with immune infiltrates in liver cancer. Biosci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1042/bsr20203115 (2021).

An, G. et al. A bioinformatics analysis of zinc finger protein family reveals potential oncogenic biomarkers in breast cancer. Gene 828, 146471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2022.146471 (2022).

Xu, F., Sun, J., Gu, X. & Zhou, Q. An innovative prognostic auxiliary for colon adenocarcinoma based on zinc finger protein genes. Transl. Cancer Res. 13, 1623–1641. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-23-2158 (2024).

Pearson, P. et al. Kruppel-family zinc finger proteins as emerging epigenetic biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 52, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-023-00640-x (2023).

Zheng, R. S. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2016. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 45, 212–220. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20220922-00647 (2023).

Crosbie, E. J. et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 399, 1412–1428. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00323-3 (2022).

Namani, A., Veeraiyan, D. & Patra, T. A comparative analysis indicates SLC7A11 expression regulate the prognostic value of KEAP1-NFE2L2-CUL3 mutations in human uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Free Radic Biol. Med. 222, 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.06.008 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Identification and validation of the important role of KIF11 in the development and progression of endometrial cancer. J. Transl. Med. 23, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06081-6 (2025).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654 (2021).

Wei, C. et al. Integrated machine learning identifies a cellular senescence-related prognostic model to improve outcomes in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 15, 1418508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1418508 (2024).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics 26, 1572–1573. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170 (2010).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587-d592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Tibshirani, R. The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Stat. Med. 16, 385–395 (1997).

Zeng, D. et al. IOBR: multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.687975 (2021).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3612 (2013).

Jiang, P. et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 24, 1550–1558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1 (2018).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 18, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019 (2017).

Xia, C. et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 135, 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000002108 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Glycosyltransferase-related prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers of uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Comput. Biol. Med. 163, 107164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107164 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. MCM10: An effective treatment target and a prognostic biomarker in patients with uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 27, 1708–1724. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.17772 (2023).

Liu, D., Enriquez, L. & Ford, C. E. ROR2 is epigenetically regulated in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13030383 (2021).

Wang, G., Fu, J., Liu, M. & Zheng, Q. CXC chemokines: Potential biomarker and immunotherapeutic target for uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. PLoS ONE 19, e0277872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277872 (2024).

Hong, S. A. et al. High endothelial venule with concomitant high CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with a favorable prognosis in resected gastric cancer. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082628 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Zhu, F., Tong, Y., Shi, D. & Zhang, J. CHD4 R975H mutant activates tumorigenic pathways and promotes stemness and M2-like macrophage polarization in endometrial cancer. Sci. Rep. 14, 18617. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69233-6 (2024).

Gu, X. et al. Exosomal transfer of tumor-associated macrophage-derived hsa_circ_0001610 reduces radiosensitivity in endometrial cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12, 818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04087-8 (2021).

Chan, T. A. et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic. Ann. Oncol. 30, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy495 (2019).

Southworth, E. et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals diverse genomic relatedness between paired concurrent endometrial and ovarian carcinomas. Eur. J. Cancer 208, 114205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2024.114205 (2024).

Molefi, T., Mabonga, L., Hull, R., Sebitloane, M. & Dlamini, Z. From genes to clinical practice: exploring the genomic underpinnings of endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020320 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. ARID1A deficiency promotes malignant proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating HDAC7/ENO1 signaling pathway. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1097/hc9.0000000000000738 (2025).

Oda, K. et al. PIK3CA cooperates with other phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase pathway mutations to effect oncogenic transformation. Cancer Res. 68, 8127–8136. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-0755 (2008).

Orang, A. et al. Basonuclin-2 regulates extracellular matrix production and degradation. Life Sci. Alliance https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202301984 (2023).

Huang, C. N. et al. Genetic polymorphisms in oestrogen receptor-binding sites affect clinical outcomes in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy. J. Intern Med. 271, 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02449.x (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. Development of a CAFs-related gene signature to predict survival and drug response in bladder cancer. Hum. Cell 35, 649–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-022-00673-w (2022).

Chahal, H. S. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel susceptibility loci for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 7, 12048. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12048 (2016).

Song, K., Xu, H. & Wang, C. The role of N6-methyladenosine methylation in the progression of endometrial cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 37, 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1089/cbr.2020.3912 (2022).

Yang, X. et al. A novel transcription factor-based prognostic signature in endometrial cancer: establishment and validation. Onco. Targets Ther. 14, 2579–2598. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S293085 (2021).

Akagi, T. et al. Chromosomal abnormalities and novel disease-related regions in progression from Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 125, 2349–2359. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24620 (2009).

Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, Y., Lu, F. & Chen, X. Decreased expression of BNC1 and BNC2 Is associated with genetic or epigenetic regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17020153 (2016).

Kang, M., Du, W., Ding, L., Wu, M. & Pei, D. HIC1 suppresses tumor progression and enhances CD8(+) T cells infiltration through promoting GSDMD-induced pyroptosis in gastric cancer. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 12, e2412083. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202412083 (2025).

Markowski, J. et al. Expression of the tumor suppressor gene hypermethylated in cancer 1 in laryngeal carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 9, 2299–2302. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2015.2983 (2015).

Zhao, T. et al. The promoter methylation drives down-regulation mode of HIC1 in gastric cancer, its molecular characteristics and downstream functional pathways. Gene 824, 146380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2022.146380 (2022).

Zhou, X., Zhang, P., Han, H., Lei, H. & Zhang, X. Hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) suppresses bladder cancer progression by targeting yes-associated protein (YAP) pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 120, 6471–6481. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.27938 (2019).

Lu, X., Jing, L., Liu, S., Wang, H. & Chen, B. miR-149-3p is a potential prognosis biomarker and correlated with immune infiltrates in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 5006123. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5006123 (2022).

Xu, T. et al. ISG15 and ISGylation modulates cancer stem cell-like characteristics in promoting tumor growth of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 42, 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-023-02751-9 (2023).

Moll, U. M., LaQuaglia, M., Bénard, J. & Riou, G. Wild-type p53 protein undergoes cytoplasmic sequestration in undifferentiated neuroblastomas but not in differentiated tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 4407–4411. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.10.4407 (1995).

Kim, I. S. et al. Truncated form of importin alpha identified in breast cancer cell inhibits nuclear import of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23139–23145. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M909256199 (2000).

Jamali, T., Jamali, Y., Mehrbod, M. & Mofrad, M. R. Nuclear pore complex: biochemistry and biophysics of nucleocytoplasmic transport in health and disease. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 287, 233–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-386043-9.00006-2 (2011).

Feng, N. et al. Analysis of microarray data on gene expression and methylation to identify long non-coding RNAs in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 6, 37233. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37233 (2016).

Noetzel, E. et al. Nuclear transport receptor karyopherin-α2 promotes malignant breast cancer phenotypes in vitro. Oncogene 31, 2101–2114. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2011.403 (2012).

Lin, J. et al. MiR-26b/KPNA2 axis inhibits epithelial ovarian carcinoma proliferation and metastasis through downregulating OCT4. Oncotarget 6, 23793–23806. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4363 (2015).

Altan, B. et al. Nuclear karyopherin-α2 expression in primary lesions and metastatic lymph nodes was associated with poor prognosis and progression in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis 34, 2314–2321. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgt214 (2013).

Ikenberg, K. et al. KPNA2 is overexpressed in human and mouse endometrial cancers and promotes cellular proliferation. J. Pathol. 234, 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4390 (2014).

Yan, M. et al. Knockdown of NR3C1 inhibits the proliferation and migration of clear cell renal cell carcinoma through activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-mitophagy. J. Transl. Med. 21, 701. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04560-2 (2023).

He, L., He, W., Luo, J. & Xu, M. Upregulated ENC1 predicts unfavorable prognosis and correlates with immune infiltration in endometrial cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 919637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.919637 (2022).

Shen, Y., Yang, P. & Lu, Y. Expression and prognosis of NR3C1 in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma based on multiple datasets. Discov. Oncol. 16, 370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-025-02086-1 (2025).

Yan, H., Ma, X., Mi, Z., He, Z. & Rong, P. Extracellular polysaccharide from rhizopus nigricans inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-494-3p/TRIM36 axis and cyclin E ubiquitination. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 10, 608–619. https://doi.org/10.14218/jcth.2021.00301 (2022).

Zhao, B. et al. TRIM36 suppresses cell growth and promotes apoptosis in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Hum. Cell 35, 1487–1498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-022-00737-x (2022).