Abstract

This paper presents a neural network model for predicting a ship’s magnetic field distribution at arbitrary depths and courses using inverse modeling. Trained on synthetic FEM-generated data, the model addresses limitations of the multi-dipole approach, which is sensitive to positional errors and computationally demanding. The data preparation process and Bayesian optimization of network architecture and hyperparameters are described. Model accuracy is assessed using various metrics and dataset sizes, with comparisons to the multi-dipole model in terms of prediction accuracy, computational cost, and robustness. When ship positioning data were disturbed, the relative deterioration of selected quality indices was six to seven times lower than for the multi-dipole model. Although requiring more data for high accuracy, the neural model is faster, more robust, and well-suited for degaussing and risk-assessment applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, ships are most often built of steel, which is a ferromagnetic material. This causes the occurrence of magnetization, which can be described by two components: permanent and induced1. Permanent magnetization is largely due to the ship’s construction process, including welding. Compasses, sensors, motors, or electric generators are also sources of permanent magnetization. Over time, this component changes through exposure to magnetic fields or temperature change, but these changes occur at a very slow rate. Induced magnetization results from the effect of the Earth’s magnetic field on the vessel and varies depending on its position and orientation. Altogether, magnetization manifests itself by perturbing the Earth’s magnetic field, which can be described using a mathematical apparatus based on Maxwell’s equations, using magnetic fields characteristic to each ship, called magnetic signatures.

In the maritime industry, magnetic signatures of ships are used for tasks such as classification, tracking, or identification2. A ship’s magnetic signature can be used to determine its type or size3. They are also a very important part of the safety issue, since magnetic mines are activated precisely on their basis4, and for this reason a highly important issue from the point of view of ship design is their minimization. To address this, degaussing systems are employed to counteract the ship’s natural signature through the use of coils installed onboard the vessel, generating a magnetic field of opposite polarity5.

A highly effective approach to designing degaussing systems is to develop an appropriate model to study the effects of various factors on the magnetic fields generated by the vessel. Commonly used methods are numerical modeling methods such as the finite element method (FEM) and the boundary element method (BEM)6.

Equally important from the point of view of magnetic signatures is their prediction at the selected course and measurement depth. Using either measured or synthetic data obtained by the aforementioned methods, it is possible to develop a regression model, such as the multi-dipole model7. This model consists of a predetermined number of permanent and induced dipoles, describing the permanent and induced magnetization of the ship, respectively. Each dipole is described by six parameters: three coordinates in a three-dimensional Cartesian system and three components of the magnetic moment vector in each orthogonal direction. These parameters are obtained through an optimization process described in8, which fits the model to the data. The model developed in this way makes it possible to predict the magnetic signature in any other direction and at any depth, but greater than that at which it was fitted to the data9. However, as shown in10,11, the multi-dipole model’s accuracy is highly sensitive to ship positioning errors, with GPS inaccuracies causing shifts and distortions in magnetic flux density measurements. These errors particularly affect the \(B_x\) and \(B_y\) components, sometimes inverting the signature, while \(B_z\) remains more stable. Monte Carlo simulations revealed deviations exceeding 3000 nT, confirming that errors along the ship’s motion direction (N-S, E-W) had the greatest impact. This motivates the search for an alternative modeling technique.

In this article, the authors continue a previously started attempt to model the magnetic signature using a neural network presented in12, where the magnetic field generated by the ship was modeled only as a function of depth, on a northerly course and under its keel. Also, only \(B_x\) and \(B_z\) components were modeled. The goal is to generalize the model to predict all three magnetic field density components at any Cartesian coordinates and ship course, giving it functionality equivalent to a multi-dipole model in that regard (the multi-dipole model also allows to decompose the signature into a permanent and induced part9, but it’s beyond the scope of this study). An important factor in evaluating the model is determining how much training data is needed for accurate predictions, specifically how many directions and measurement depths they must come from. The process of selecting an appropriate network structure and optimizing hyperparameters will be presented. The motivation for addressing this topic lies in the high precision in data analysis and modeling offered by machine learning algorithms, with the goal of improving modeling precision. The use of ANNs improves the scalability of analyses and makes it possible to deal with complex patterns in the data.

The main contributions of this paper are:

-

Development and optimization of a neural network model capable of predicting a full distribution of a ship’s magnetic field at an arbitrary depth and course,

-

Extensive computer simulations determining the impact of the number of data samples on the prediction quality by determining six different quality indicators allowing for a comprehensive assessment,

-

Comparative analysis of the developed method with the multi-dipole model in terms of both the prediction quality using aforementioned indicators and robustness in terms of ability to refute noise in data and position-related errors.

Numerous simulations have been carried out during the writing of this article, all of which were carried out using the computers of Centre of Informatics Tricity Academic Supercomputer & Network.

Related works

Ferromagnetic signature modeling of ships has its origins in World War II and was aimed at determining their vulnerability to magnetically triggered mines. The same models were also used to evaluate and optimize the performance of signature reduction systems during their design phase, as well as in the development of both offensive and defensive military systems1. Due to the limited computational capabilities of the time, detailed physical-scale models were often used, with signatures measured in laboratories specially made for this purpose, and remained the main method for their prediction until the 1980s6. The development of computers and numerical modeling techniques allowed accurate simulations of magnetic fields using FEM and BEM, making it possible to determine the so-called forward model, a model arising from the structure of an object using analytical methods. Due to the small ratio of sheet thickness to vessel size, numerical modeling requires a dense mesh with a huge number of finite elements. In addition, the presence of permanent magnetization complicates the modeling process and significantly increases the computation time; moreover, when changing course, the model must be recalculated13. Hence, a common simplification of the model is the use of an ellipsoid, which is a widely accepted representation of the ship’s hull14.

Given the above-mentioned limitations, the inverse models, also called semi-empirical or equivalent-source models, are very popular. They are used to reconstruct input parameters based on observed output data either from measurements or from the numerical environment15. Several solutions to the inverse modeling problem can be found in the literature, the most widely used of which are two:

-

The multi-dipole model - approximates the magnetic field using a set of magnetic dipoles. By selecting the moments and positions of the dipoles, it is matched to the observed data16,

-

Prolate Spheroidal Harmonic (PSH) model—a method of representing a vessel’s magnetic field by means of expansion into a series of harmonic functions described by elliptical coordinates17.

These models, using appropriate regression techniques, are able to predict a vessel’s magnetic signature from observed data. In addition, recent analytical and semi-analytical methods have also been developed for magnetic signature modeling. Extended dipole formulations have been proposed in which the ship is represented as a hollow cylinder, allowing analytical determination of the induced magnetic field under local geomagnetic conditions18. Other works address decomposition of the magnetic signature into permanent and induced components using inverse problem regularization based on multiple passages over magnetic ranges19. Composite field models have also been proposed by combining ellipsoidal representations with magnetic dipole arrays, improving conditioning of the problem and computational efficiency without compromising modeling accuracy20. In parallel to these modeling developments, metamaterial structures have been investigated as a means of reducing magnetic signatures, exploring materials and geometries that inherently suppress magnetic response, potentially providing a complementary engineering pathway to signature reduction rather than predictive modeling21. These analytical and material-based approaches provide strong physical interpretability and can achieve high accuracy when well parameterized, but typically still require tailored modeling or experimental characterization for each vessel case.

An alternative modeling technique that has revolutionized the ability to map complex relationships over the past few decades is deep learning based on neural networks, which, thanks to their ability to learn high-abstraction data representations, enable accurate modeling and forecasting in various fields of science, technology, and data analysis.

With the development of artificial intelligence, its applications in the maritime industry are increasingly found in the literature. A comprehensive review of these was done in 202322, where 69 works done in this area in the last ten years were analyzed. It listed works on image-based ship classification using convolutional networks, such as AlexNet23, YOLOv424 and Grid CNN25. Convolutional networks were also used to classify ships based on images from Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)26,27 and infrared28. Applications in course optimization using unidirectional networks29,30 and recurrent networks31,32 were also presented. Other applications included issues of ship condition monitoring and maintenance33,34,35, ship autopilot implementation36,37,38, and safety improvement in navigation39,40,41.

In the case of ship magnetic signatures, an example of the use of neural networks is42, where the authors studied the accurate prediction of magnetic signatures in the context of active degaussing, looking at the effect of changes in hull thickness, relative permeability, and object radius. Their work proposed a machine learning method based on multiple linear regression as a more effective alternative to traditional methods. The accuracy, speed, and precision of this method were demonstrated. In43, the authors proposed a method for detecting magnetic anomalies using a multi-objective transfer learning algorithm that simultaneously removes noise and detects magnetic anomalies in data with a limited number of samples. The model simultaneously uses a convolutional autoencoder network and a unidirectional network for adaptive background noise modeling and pattern learning, as well as noise filtering and anomaly detection. The developed model achieved significantly better results compared to traditional methods and showed better performance. Ref.44 presents the use of a hybrid artificial neural network with a genetic algorithm to predict the induced magnetic signature with high efficiency. Magnetic signatures have also been used to classify ships using one-way networks45,46,47. Acoustic signals were also used for46 and47.

To the authors’ knowledge, it is a novelty to employ neural networks to model all three components of a ship’s magnetic signature directly at once for an arbitrary position relative to the hull and also for any course.

Synthetic FEM data

A numerical model of a corvette-type ship was developed in the Simulia Opera48 computational environment, as shown in Fig. 1. The model was created from plates modeling the ship’s hull and reflecting its geometry and structural properties. The boundary condition for the magnetic potential was taken to be \(H_{ext}=-\nabla \psi _m\), where \(H_{ext}\) is the intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field and \(\psi _m\) is the magnetic scalar potential.

A thin plate boundary condition method was used to introduce the thickness of the plates10,49, which allows the use of fewer nodes connecting the finite elements while maintaining the accuracy of the calculation by taking into account that one of the three dimensions of the plates is significantly smaller than the others. In the end, the model consists of 906,792 nodes and 4,319,341 linear elements. Selected parameters of the model are listed in table 1, where \(\mu _r\) is the relative magnetic permeability and d is the hull’s plates’ width.

In order to account for the vessel’s permanent magnetization, 13 coils with constant currents were added to the model, as shown in Fig. 2. The inserted set consists of three coils placed flat in the XY plane, three each placed on both sides of the hull in the XZ plane, and four placed flat in the YZ plane. The current flow in the coils generates a magnetic field that models the permanent magnetization in the ship’s structural elements. The current densities in the coils were chosen arbitrarily to noticeably increase the magnetic field generated by the ship.

In order to simulate the magnetic field produced by the ship, it is necessary to determine its position on the Earth, since it is not uniform on its surface. This position was set as (55\(^{\circ }\)N, 2\(^{\circ }\)E), that is, in the North Sea, where the modulus of the Earth’s magnetic field density \(B_{ext}\) is approximately 50nT. The magnetic inclination \(\delta\) at this location is approximately 70\(^{\circ }\). From here, the magnetic field strength H necessary for the simulation can be determined, specifically its horizontal component \(H_{xy}\) and its vertical component \(H_z\), as described by the Eqs. (1) and (2).

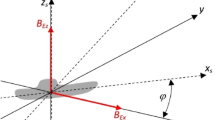

For a complete representation of the spatial distribution of the magnetic field with respect to the movement of the ship, its course \(\phi\) should be taken into account, determined as 0\(^{\circ }\) for the north direction and calculated counterclockwise (Fig. 3).

In order to train the neural network, a large dataset is required, so magnetic fields were generated for courses 0, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 120, 135, 150, 165, 180, 210, 225, 240, 255, 270, 300, 315, 330, and 345 degrees. The generated \(B_x\), \(B_y\), and \(B_z\) components were evaluated on a grid ranging from -300 to 300 m in the X and Y directions and -50 to -10 m in the Z direction, all with 1 m steps.

Training data

The “cubes” of magnetic flux density values generated in Simulia Opera do not reflect the actual measurement of the ship’s magnetic signature, which is usually performed with a magnetometer array placed at some depth50,51. Given this fact, training data for the neural network was created based on three variables: step of the ship’s course (how many passages over the magnetometers were considered), number of sensors in the Y-axis, and number of sensors in the Z-axis. All the data in the X-axis from -300 to 300 m with 1 m steps were acquired, while the other axes were collected as shown in Fig. 4 (with 30 m steps for better visualization, actually 1 m steps were used), where example sensor arrays were depicted.

The spacing between the sensors in the Y coordinate is assumed to be 10 m, and in the Z coordinate to be 4 m. This allowed for a simulation of the ship passing over an array of magnetometers.

The calculated vectors of positions are then rotated according to the current ship’s course angle using a 2D rotation matrix, as described in Eq. (3).

This rotation accounts for changes in ship orientation during data collection. When considering the influence of the dataset size on the network’s performance, a term “course step” will be used, meaning the difference between subsequent paths in degrees for extracting training data, as visualized in Fig. 5. The lower the course step, the more data will be used.

When considering the total number of samples N in the training set based on the number of sensors in Y, the number of sensors in Z, and the course step marked as \(N_Y\), \(N_Z\), and \(\Delta \phi\) respectively, it can be calculated using the formula (4).

Here, 601 refers to the number of samples in the range from \(-300\) to 300 m (single path), with 1 m step.

The dataset, which contains measurements of magnetic field components, is filtered to select data points that match the calculated sensor positions and orientations. For each valid data point, the coordinates (x, y, z) and the sine and cosine of the ship’s heading are paired with the corresponding magnetic field values. Using the sine and cosine here instead of a single 0-360\(^\circ\) or 0-2\(\pi\) angle as inputs to the neural network ensures a more effective representation of directional information. The multi-dipole model also uses this information. This approach addresses the circular nature of the course, where \(0^\circ\) and \(360^\circ\) are equivalent, by providing a continuous and unambiguous representation that avoids discontinuities. Sine and cosine also maintain the geometric relationships between headings, providing the network with more meaningful information about orientation. Additionally, these values are being normalized to the range [\(-1,1\)], which is typical for neural network input preprocessing. While adding an extra input dimension, the sine and cosine representation improves the network’s performance and enhances generalization, particularly for physical phenomena like magnetic fields that depend on orientation. This way, a labeled training dataset is produced where the input consists of measurement positions and orientation, and the output consists of the magnetic flux density values.

Discussion on the network’s type and optimization of the networks’its structure and hyperparameters

The model proposed in this paper consists of five inputs (three spatial coordinates relative to the ship and sine and cosine of its course) and three outputs corresponding to three components of the magnetic flux density. For accurate signature reproduction, the types of layers between inputs and outputs and the networks’ hyperparameters should be optimized. The selection of the appropriate type of neural network for modeling a ship’s magnetic signature is a difficult task, since there are so many to choose from. The choice depends on the problem’s nature, the data characteristics, and the specific goals of the model. In the case of this study, a strongly nonlinear relation between the Cartesian coordinates and the ship’s course and the magnetic flux density generated by that ship is attempted to be mapped. Three main candidates were considered for this task: a multilayer perceptron (MLP), a recurrent neural network (RNN), and a convolutional neural network (CNN). Since the data is magnetostatic and spatial data will not be considered, the MLP is the architecture that was chosen.

For the time of optimization of the network’s structure and hyperparameters, the training set was chosen to be for \(\Delta \phi = 60^\circ\), \(N_Y = 9\), \(N_Z = 5\). The validation data came from the 143.5\(^\circ\) course with \(N_Y = 9\) with 15 m spacing and \(N_Z = 4\) with 4 m spacing. The test data was a set of paths from the 320.5\(^\circ\) course with \(N_Y = 9\) with 12 m spacing and \(N_Z = 4\) sensors with 6 m spacing.

In previous works, the authors used grid search and random search for hyperparameter optimization. This time, it was decided to use the Bayesian optimization procedure, which is a probabilistic model-based approach for optimizing hyperparameters of machine learning models. The decision variables in this case were number of neurons, activation functions, learning rate, batch size, and maximum number of epochs. The number of neurons in each layer was limited to 10 times the number of the network’s outputs, 300. The activation function in each layer was selected from ReLU, Leaky ReLU, ELU, GELU, Swish, and Tanh. Lower boundaries for learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs were selected as \((10^{-5},10^{-1})\), (16, 512), and (10, 50), respectively. The Adam optimizer was chosen for the network training algorithm. The objective function was the network’s performance on the test set calculated via the root mean squared error (RMSE) given by (5) for N samples.

where \(y_i\) is the actual value of the ith sample and \(\hat{y}_i\) is the modeled value of the i-th sample. For each function evaluation, the network was trained on the training set, and the one achieving the best validation performance was selected. Since each network depth corresponds to a different number of decision variables, the optimization was conducted separately for each case from 1 to 12 layers, searching for the optimal number of neurons and activation function in each layer. Additionally, since the results are non-deterministic, the procedure was repeated ten times for each layer. Then, for every best-performing network from each optimization procedure, the training process was repeated once again ten times, and the results were averaged. In the end, the selected model was the one that, on average, performed the best on the test set. Figure 6 shows the distribution of RMSE values for neural networks with 1 to 12 layers. Each box represents 10 training runs for a given number of layers. The RMSE is measured in nT. The network with one hidden layer had big RMSE values, rendering the plot unreadable. Therefore, it was not depicted here.

It can be seen that for 7, 8, and 12 layers, the mean RMSE values were the lowest, with the best-performing network being a 7-layered one, a diagram of which is shown in Fig. 7. Its hyperparameters are a learning rate of \(2.23 \times 10^{-4}\), a batch size of 403, and 30 maximum training epochs. This seven-layer neural network structure was used in all subsequent analyses to evaluate the influence of the training set size on the prediction accuracy of the ship’s magnetic signature.

Figure 8 shows the network’s prediction of a magnetic signature for one of the paths in the test set (\(y = 12 \ m\), \(z = -32 \ m\), and \(\phi = 320.5^\circ\)). The training dataset in this case was the same as during the hyperparameters’ optimization. The model fits the data well, as shown by the close alignment between the predicted values and the observed data points on the graph. It took 190 seconds to complete the network’s training.

Influence of the training dataset size on magnetic signature prediction

Determining the number of data samples necessary for the network’s satisfactory prediction of a ship’s magnetic signature requires assessing the fidelity of the model’s outputs via qualitative measures, such as previously used RMSE. It was decided to also include other indices in order to make the evaluation more comprehensive. These include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) given by (6), Median Absolute Error (MdAE) given by (7), Median Absolute Percentage Error (MdAPE) given by (8), R\(^2\), given by (9), and Inter-quartile Range in Levels (IQLev), given by (10).

where \(\bar{{\bf y}}\) denotes the average value of the vector \({\bf y}\).

where \(\left| {\bf y}-\hat{{\bf y}} \right| _{75}\) and \(\left| {\bf y}-\hat{{\bf y}} \right| _{25}\) denote the 75th and 25th percentiles of absolute errors, respectively. The use of the aforementioned indicators allows for a comprehensive assessment of the quality of the model by providing information on every aspect of the error distribution, including central tendency (RMSE, MAE, MdAE), relative error (MdAPE), goodness of fit (\(R^{2}\)), and the variability of the prediction errors (IQLev).

The network developed in previous section was trained for different cases of \(\Delta \phi\) and the number of sensors in the Y and Z directions. Then, for each training, it was evaluated on a test set of data for courses 75, 165, 255, and 345 degrees, for \(N_Y = 10\) and \(N_Z = 4\), also with different spacing between the sensors, 12 m and 5 m for Y and Z, respectively. The results were visualized using heatmaps in Figs. 9 and 10 for the case of \(\Delta \phi = 30^\circ\).

Looking at the heatmaps, it can be determined that, unsurprisingly, more than one sensor in each direction is necessary for accurate signature prediction. Also, in every quality indicator, a poor performance can also be seen for two sensors in Y. Then the errors rapidly decrease with increasing the number of Y sensors from 3 to 7. A pattern starts to emerge where the lowest error values depending on the number of Z sensors, are between 3 and 8. After that, there is no significant improvement in any of the indices. An area of minimal errors can be identified for \(NY \ge 13 \wedge 4\le NZ \le 7\).

Presenting heatmaps for every \(\Delta \phi\) would be an exaggeration. Therefore, only RMSE is shown for the other course steps in Fig. 11. Deterioration can be seen in the values of the indices as \(\Delta \phi\) increases, while their distributions according to NY and NZ remain consistent. Other indices showed similar worsening.

It is clear that \(\Delta \phi\) has a significant influence on the prediction quality. This has been visualized in Figure 12, depicting the signatures predicted for \(y = 7 \ m\), \(z = -23 \ m\)and \(\phi = 255^\circ\) by models that were trained with \(N_Y=4\) and \(N_Z=6\), but with different \(\Delta \phi\).

Comparison with the multi-dipole model

The multi-dipole model is an abstract structure consisting of m permanent and n induced dipoles, described by six parameters: the three components of the magnetic moment vector (mx, my, and mz) and three coordinates in a Cartesian coordinate system. It is created on the principle of inverse modeling, that is, on the basis of regression using data. The detailed description of the model can be found in8,9.

The vector of magnetic field induction B at position (x,y,z) produced by the i-th dipole at position (xi,yi,zi) is described by the relations (11)-(12)52. With the help of such a model, the signature can be reproduced at any depth (provided that it is lower than the one at which the model was trained9) and in any direction.

where:

The total magnetic field \({\bf B}_T\) produced by the model is described by the relation (13) for m permanent and n induced dipoles.

The number of dipoles in the model for the current state of knowledge is chosen arbitrarily52 and is a compromise between accuracy and computational complexity. A multi-dipole model is a regression model determined by optimization through the use of the nonlinear least squares method. The goal is to minimize the squares of the difference between the source data \({\bf {B}}_{l,d}^{ref}(j,k)\) and the model-derived data \({\bf {B}}_{l,d,\Omega }^{model}(j,k)\), depending on the parameters \(\Omega\) (dipole positions and moments), as described by Eqs. (14) and (18).

subject to

where

The model is fit to data using the lsqnonlin function available in MATLAB for \(m = 25\) and \(n = 25\). The maximum number of iterations is set to 106. Also, a validation function was implemented which halted the optimization process if for 500 iterations no improvement was made.

Prediction accuracy and training time

To compare models directly, the same approach was used as previously, where the multi-dipole model was trained with different dataset sizes. The training time, however, is significantly longer than when it comes to training a neural network, therefore the tests were performed only for \(\Delta \phi = 90^\circ\). The RMSE heatmap for the model is shown in Fig. 13.

It can be seen that while both models are able to achieve low error prediction values, the multi-dipole model needs significantly less training data. Above 5 sensors in the Y plane there was not much improvement gained from increasing the dataset size. The direct impact of dataset size on both models’ training efficiency has been visualized in Fig. 14, where all six considered quality indices are shown in relation to the number of training data samples for both models. While the black-box nature of artificial neural networks makes them require more data to train, it is clear that compared to the multi-dipole model they need less time for this training (by approximately an order of magnitude).

Robustness

Another aspect of the model, known as robustness, was also tested to evaluate its usefulness in simulated real-world conditions. Three scenarios were assumed here. First scenario was a gaussian white noise of varying power \(P_N\) (0, 1, 2, 5 and 10 nT) added to the training outputs. Second scenario was the errors in positions implemented using a Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC), namely the Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm, where samples from \(\mathcal {N}(0,\delta )\) were drawn using a proposal distribution \(\mathcal {U}(-1,1)\), where \(\delta\) was varied (0, 1, 2, 5 and 10 m). The starting point of the sequence was also drawn from \(\mathcal {N}(0,\delta )\). This method allows to approximate any distribution using samples from a proposal one, as described in11 The influence of this method on the paths in the training inputs (x and y coordinates) was illustrated in Fig. 15 for \(\Delta \phi = 90^{\circ }\). The third method combined the previous two, adding errors to both outputs and positions.

The reconstruction quality indices described earlier were evaluated for each disturbance case for the training data scenario \(N_Y = 6, N_Z = 4\), but \(\Delta \phi = 90^{\circ }\) for the multi-dipole model and \(\Delta \phi = 30^{\circ }\) to provide a more equal contest. This was repeated ten times for each disturbance case, and the results were averaged. Table 2 shows how all indices’ values were distributed across different disturbance cases for both models, while Tables 3 and 4 present the average (across all indices) percentage increase (or decrease in case of R2) of these indices due to perturbations, relative to the undisturbed prediction errors, for the neural network and multi-dipole model, respectively. This was calculated according to the formula (19).

where \(D_{\delta ,P_N}\) is the average deterioration for a given \(\delta\) and noise power \(P_N\), S is the given disturbance case, |S| is the number of occurrences of the disturbance case, \(Q_{j,k}\) represents the k-th quality index for data point j, and \(Q_{ref,k}\) is the k-th quality index for the baseline case (\(\delta = 0\), \(P_N=0\)). Using these three tables, one can see both the absolute and relative impact of the disturbances on the models.

It can be inferred from the tables that while both models experience some level of performance deterioration, the neural network generally demonstrates greater robustness, showing smaller average increases in error indices under perturbation. In contrast, the multi-dipole model exhibits higher sensitivity to disturbances, with larger relative error increases observed in most cases. This indicates that the neural network maintains more consistent performance and is less affected by external disturbances compared to the physics-based multi-dipole model.

Figure 16 shows a magnetic signature predicted by both models for \(y = -11 m, z = -37 m, \phi = 345^{\circ }, \delta = 0.5\) and \(P_N = 2\), while Fig. 17 shows the same signature predicted for \(\delta = 5\) and \(P_n = 5\), with RMSE values for each component in the title of the corresponding plot. It can be seen that while with lower values of disturbance the performance of the neural network keeps being poorer than that of the multi-dipole model, it exceeds the latter with higher noise and position error values. It needs to be noted, however, that the magnetic field can be decomposed into the permanent and induced part using the multi-dipole model9, the possibility which the neural network does not offer in this state, as it predicts the whole magnetic field density distribution, which is a superposition of the permanent and induced part.

Conclusions & future research

In this article, the case of using a neural network for modeling a ship’s magnetic signature was presented. By utilizing a FEM environment for the generation of synthetic data of a corvette-type ship’s magnetic field density distribution, a labeled training dataset was created, with position relative to the hull and the ship’s course as the inputs and with three components of the magnetic flux density vector as the outputs. The network’s hyperparameters and structure were optimized using Bayesian optimization and the number of necessary data samples for accurate signature prediction was determined using extensive computer simulations. The results show that the neural network should be trained with data coming from more than just the cardinal directions in order to obtain a good prediction quality. Using these findings, a compromise between the number of data samples and prediction accuracy can be found.

The neural network model presented in this study demonstrates strong potential for predicting a ship’s magnetic signature at arbitrary depths and courses. In comparison to the state-of-the-art multi-dipole model, proposed approach has greater robustness against position-related errors. The results showcased that by disturbing the input data related to the ship’s positioning, the relative deterioration of chosen quality indices was six to seven times lower than in the case of the multi-dipole model. Along with lower computational costs, the neural network’s prediction ability could make it well-suited for real-time signature estimation, that can be used for active degaussing and/or mine activation risk assessment.

When it comes to limitations of the model, one has to name the need for high amount of training data, much larger when compared to the multi-dipole model. Furthermore, the network in this state does not allow for separation of the permanent and induced magnetization, thus when the ambient background field changes significantly, the model needs to be retrained.

For future research, the use of Integral Equation–based solvers such as BEM or Method of Moments (MoM) may offer an efficient alternative to FEM for synthetic data generation. The authors also plan to incorporate real-world data, treating synthetic data as a starting point. Actual measurement data could introduce complexities that cannot be fully captured in simulations, and would be a great source of training data. While on-board measurements, which have been previously conducted with ship Zodiak, provided valuable data, a possibility of using a rotating platform with a scale ship model, which would be a source of what is really an unlimited amount of magnetic field distribution data. Aside from the uncertainty in the track of the vessel along the sensor, the sensor position uncertainty could also be addressed in future work. Additionally, a hybrid approach combining the multi-dipole model with the neural network model could be considered.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, K. Z., upon reasonable request.

References

Holmes, J. J. Exploitation of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures (Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2006).

Zielonacki, K., Tarnawski, J. & Woloszyn, M. Ship magnetic signature classification using GRU-based recurrent neural networks. IEEE Access 13, 59514–59530. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3557331 (2025).

Baltag, O. & ROŞU, G. Analytical and physical modeling of the naval magnetic signature. FIZICĂ 35 (2016).

Isa, C. et al. An overview of ship magnetic signature and silencing technologies. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14643.58401 (2019).

Holmes, J. J. Reduction of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures (Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2008).

Holmes, J. J. Modeling a Ship’s Ferromagnetic Signatures (Springer, 2007).

Sheinker, A., Ginzburg, B., Salomonski, N., Yaniv, A. & Persky, E. Estimation of ship’s magnetic signature using multi-dipole modeling method. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 57, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2021.3062998 (2021).

Tarnawski, J., Cichocki, A., Rutkowski, T. A., Buszman, K. & Woloszyn, M. Improving the quality of magnetic signature reproduction by increasing flexibility of multi-dipole model structure and enriching measurement information. IEEE Access 8, 190448–190462. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3031740 (2020).

Woloszyn, M. & Tarnawski, J. Magnetic signature reproduction of ferromagnetic ships at arbitrary geographical position, direction and depth using a multi-dipole model. Sci. Rep. 13, 14601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41702-4 (2023).

Jankowski, P. & Woloszyn, M. Applying of thin plate boundary condition in analysis of ship’s magnetic field. COMPEL Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 37, 1609–1617. https://doi.org/10.1108/COMPEL-01-2018-0032 (2018).

Tarnawski, J., Buszman, K., Woloszyn, M. & Puchalski, B. The influence of the geographic positioning system error on the quality of ship magnetic signature reproduction based on measurements in sea conditions. Measurement 229, 114405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114405 (2024).

Zielonacki, K. & Tarnawski, J. Neural network model of ship magnetic signature for different measurement depths. In 2024 28th International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR). 328–333. https://doi.org/10.1109/MMAR62187.2024.10680779 (IEEE, 2024).

Le Dorze, F., Bongiraud, J., Coulomb, J., Labie, P. & Brunotte, X. Modeling of degaussing coils effects in ships by the method of reduced scalar potential jump. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 34, 2477–2480. https://doi.org/10.1109/20.717570 (1998).

Synnes, S. A., Brodtkorb, P. A. & Lepelaars, E. Representing the ship magnetic field using prolate spheroidal harmonics—A comparative study of methods. In MARELEC 2006 (2006).

Jeung, Giwoo, Yang, Chang-Seob., Chung, Hyun-Ju., Lee, Se-Hee. & Kim, Dong-Hun. Magnetic dipole modeling combined with material sensitivity analysis for solving an inverse problem of thin ferromagnetic sheet. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 45, 4169–4172. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2009.2021853 (2009).

Jakubiuk, K., Zimny, P. & Wołszyn, M. Multidipoles model of ship’s magnetic field. Int. J. Appl. Electromagnet. Mech. 39, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAE-2012-1459 (2012).

Nilsson, M. S. Modelling of civilian ships’ ferromagnetic signatures. In Technical Report. ISBN: 8246427431, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (2016).

Zivieri, R. & Crupi, V. Extended dipole approximation of a ship induced magnetic signature modeled by means of a hollow cylinder. J. Magnet. Magnet. Mater. 632, 173484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2025.173484 (2025).

Hall, J.-O., Claésson, H., Kjäll, J. & Ljungdahl, G. Decomposition of ferromagnetic signature into induced and permanent components. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 56, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2019.2953860 (2020).

Lu, B. & Zhang, X. An improved composite ship magnetic field model with ellipsoid and magnetic dipole arrays. Sci. Rep. 14, 4070. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54848-6 (2024).

Distefano, F., Zivieri, R., Epasto, G., Pantano, A. & Crupi, V. Metallic metamaterials for reducing the magnetic signatures of ships. Metals 15, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15030274 (2025).

Assani, N., Matić, P., Kaštelan, N. & Čavka, I. R. A review of artificial neural networks applications in maritime industry. IEEE Access 11, 139823–139848. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3341690 (2023).

Dao-Duc, C., Xiaohui, H. & Morère, O. Maritime vessel images classification using deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology. 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1145/2833258.2833266 (ACM, 2015).

Petković, M., Vujović, I., Kaštelan, N. & Šoda, J. Every vessel counts: Neural network based maritime traffic counting system. Sensors 23, 6777. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23156777 (2023).

Zhang, T. & Zhang, X. High-speed ship detection in SAR images based on a grid convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 11, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11101206 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Multi-scale ship detection algorithm based on a lightweight neural network for spaceborne SAR images. Remote Sens. 14, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14051149 (2022).

Chen, C., He, C., Hu, C., Pei, H. & Jiao, L. A deep neural network based on an attention mechanism for SAR ship detection in multiscale and complex scenarios. IEEE Access 7, 104848–104863. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2930939 (2019).

Mishra, N. K., Kumar, A. & Choudhury, K. Deep convolutional neural network based ship images classification. Defence Sci. J. 71, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.14429/dsj.71.16236 (2021).

Daranda, A. Neural network approach to predict marine traffic. Trans. Balt. J. Mod. Comput 4, 483 (2016).

Jin, X., Xiong, J., Gu, D., Yi, C. & Jiang, Y. Research on ship route planning method based on neural network wave data forecast. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 638, 012033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/638/1/012033 (2021).

Zhu, F. Ship short-term trajectory prediction based on RNN. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 012023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2025/1/012023 (2021).

Suo, Y., Chen, W., Claramunt, C. & Yang, S. A ship trajectory prediction framework based on a recurrent neural network. Sensors 20, 5133. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185133 (2020).

Niksa-Rynkiewicz, T. et al. Monitoring regenerative heat exchanger in steam power plant by making use of the recurrent neural network. J. Artif. Intell. Soft Comput. Res. 11, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.2478/jaiscr-2021-0009 (2021).

Liang, S., Yang, J., Wang, Y. & Wang, M. Fuzzy neural network in condition maintenance for marine electric propulsion system. In 2014 IEEE Conference and Expo Transportation Electrification Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITEC-AP.2014.6941252 (IEEE, 2014).

Raptodimos, Y. & Lazakis, I. An artificial neural network approach for predicting the performance of ship machinery equipment. In Maritime Safety and Operations 2016 Conference Proceedings (University of Strathclyde Publishing, 2016).

Zhang, Y., Hearn, G. & Sen, P. A neural network approach to ship track-keeping control. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 21, 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1109/48.544061 (1996).

Le, T. T. Ship heading control system using neural network. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 26, 963–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00773-020-00783-w (2021).

Lou, R., Wang, W., Li, X., Zheng, Y. & Lv, Z. Prediction of ocean wave height suitable for ship autopilot. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 23, 25557–25566. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3067040 (2022).

Zhao, L. & Shi, G. Maritime anomaly detection using density-based clustering and recurrent neural network. J. Navig. 72, 894–916. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0373463319000031 (2019).

Zhang, W., Feng, X., Goerlandt, F. & Liu, Q. Towards a convolutional neural network model for classifying regional ship collision risk levels for waterway risk analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 204, 107127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.107127 (2020).

Vukša, S., Vidan, P., Bukljaš, M. & Pavić, S. Research on ship collision probability model based on Monte Carlo simulation and bi-LSTM. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10081124 (2022).

Modi, A. & Kazi, F. Magnetic-signature prediction for efficient degaussing of naval vessels. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 56, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2020.3010421 (2020).

Wang, S., Zhang, X., Qin, Y., Song, W. & Li, B. Marine target magnetic anomaly detection based on multitask deep transfer learning. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 20, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2023.3273722 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhou, G., Wang, K. & Zhu, X. Prediction on the induced magnetic signature of ships using genetic neural network. In The Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of China Electrotechnical Society (Liang, X., Li, Y., He, J. & Yang, Q. eds.). Vol. 890. 592–605 (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1870-4_64 (series title: Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering).

Arantes Do Amaral, J., Botelho, P., Ebecken, N. & Caloba, L. Ship’s classification by its magnetic signature. In 1998 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks Proceedings. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (Cat. No.98CH36227). Vol. 3. 1889–1892. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN.1998.687146 (IEEE, 1998).

Axelsson, O. & Rhen, C. Neural-network-based classification of commercial ships from multi-influence passive signatures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 46, 634–641. https://doi.org/10.1109/JOE.2020.2982756 (2021).

Jie, X., Jinfang, C., Guangjin, H. & Xiudong, Y. A neural network recognition model based on ship acoustic-magnetic field. In 2011 Fourth International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design. 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCID.2011.42 (IEEE, 2011).

Dassault Systèmes. Opera (2023).

Christopher, S., Biddlecombe, C. & Riley, P. Improvements to finite element meshing for magnetic signature simulations. In MARELEC 2015 Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA (2015).

Tarnawski, J. et al. Measurement campaign and mathematical model construction for the ship Zodiak magnetic signature reproduction. Measurement 186, 110059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2021.110059 (2021).

Holmes, J. J. Past, present, and future of underwater sensor arrays to measure the electromagnetic field signatures of naval vessels. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 49, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.4031/MTSJ.49.6.1 (2015).

Tarnawski, J., Rutkowski, T. A., Woloszyn, M., Cichocki, A. & Buszman, K. Magnetic signature description of ellipsoid-shape vessel using 3d multi-dipole model fitted on cardinal directions. IEEE Access 10, 16906–16930. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3147138 (2022).

Funding

Financial support of these studies from Gdańsk University of Technology by the DEC-39/1/2024/IDUB/III.4c/Tc grant under the Technetium Talent Management Grants - ‘Excellence Initiative - Research University’ program is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, creation of original draft and visualization. J.T. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation and editing. M. W. contributed to provision of software and resources, supervision and project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zielonacki, K., Tarnawski, J. & Woloszyn, M. Neural network for predicting ship magnetic signatures at arbitrary depths and courses: a comparison with the multi-dipole model. Sci Rep 15, 44758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28425-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28425-4