Abstract

Survival outcomes for infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation vary widely across neonatal units. This national, prospective cohort study evaluated 919 infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation in South Korea between 2013 and 2022, using Korean Neonatal Network data. Infants were categorized based on the level of neonatal care: 785 in lower-level centers (Group A) and 134 in higher-level centers (Group B). Survival was significantly higher in Group B (64.9%) compared to Group A (29.3%) (P < 0.0001). Early deaths occurred more frequently and earlier in Group A. Proactive care—including antenatal corticosteroids, antenatal antibiotics, and immediate surfactant administration—was more common in Group B. Antenatal corticosteroid was significantly associated with reduced risk of death (hazard ratio 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.49–0.69; P < 0.0001). The timing of rapid decline in survival was delayed in higher-level centers. In addition, classifying institutions into higher- and lower-level groups according to the survival of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation (≥50% vs. <50%) provides a good reflection of the quality of neonatal care. These findings highlight the importance of proactive care and timely in utero transfer to higher-level units in improving survival for peri-viable infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancements in neonatal intensive care have lowered the limit of viability to as early as 22–23 weeks’ gestation. However, infants born at this extremely low gestational age face high mortality and significant risks of severe neurodevelopmental impairment. Survival rates at this limit of viability are highly dependent on proactive perinatal and neonatal interventions, the quality of care, the experience of medical personnel, and the overall capability of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Ethical and legal considerations surrounding proactive care provision for infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation further contribute to marked variation in clinical practices among different institutions and countries1.

Previous studies have consistently shown that survival among extremely preterm infants significantly depends on NICU quality and proactive management strategies. Research from the Korean Neonatal Network (KNN) validated survival rates at 23–24 weeks’ gestation as a robust indicator of NICU care quality and NICU performance is frequently defined based on survival outcomes at this gestational range2,3,4,5,6. Moreover, national surveys from Japan, Sweden, and the United States have demonstrated survival rates exceeding 50% at 22 weeks’ gestation in centers providing proactive care7, although the balance between survival and severe neurodevelopmental outcomes remains challenging8,9.

In this study, we aim to investigate whether NICU quality, also correlates with survival outcomes and the timing of death in infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation. By examining whether the survival rate of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation is associated with institutional characteristics, we aim to evaluate the validity of NICU quality assessments for infants at the limits of viability. This analysis provides essential evidence to guide strategic decisions, including centralization of care and refinement of proactive neonatal management policies, ultimately improving outcomes for these infants.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Of the total 919 infants, 196 were born at 22 weeks’ gestation and 723 at 23 weeks’ gestation. A total of 785 infants were included in Group A and 134 in Group B. There were no significant differences in the proportion of males, the proportion of small for gestational age (SGA) infants, or the Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes between Group A and Group B. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy was significantly more common in Group B (86.4%) compared to Group A (69.4%) (P < 0.0001). At 22 weeks’ gestation, the rates were 55.6% in Group A and 71.4% in Group B (P = 0.2502), while at 23 weeks’ gestation, Group B had a significantly higher rate (88.1%) than Group A (73.5%) (P = 0.0007). Antenatal antibiotic therapy was significantly more common in Group B (86.6%) than in Group A (73.4%) (P = 0.0226). At 22 weeks’ gestation, the rates were 76.7% in Group A and 85.7% in Group B (P = 0.5868), while at 23 weeks’ gestation, Group B had a significantly higher rate (86.7%) compared to Group A (72.7%) (P = 0.0235). (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups in maternal chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), rates of cesarean delivery, maternal gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal pregnancy-induced hypertension, or maternal age.

Resuscitation at birth according to gestational age

The survival rate of infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation was 17.3% (34/196), and at 23 weeks’ gestation, it was 39.1% (283/723). The survival rate of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation was 64.9% in Group B and 29.3% in Group A (P < 0.0001). At 22 weeks’ gestation, the survival rate was 50.0% in Group B and 14.8% in Group A (P = 0.0008), and at 23 weeks’ gestation, 66.7% in Group B and 33.7% in Group A (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Most infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation received resuscitation at birth, including positive pressure ventilation (Group A: 97.8%, Group B: 100.0%) and endotracheal intubation (Group A: 98.2%, Group B: 99.3%). Surfactant was also administered in the majority of these infants (Group A: 98.7%, Group B: 99.3%). The proportion of infants who received surfactant immediately after birth in the delivery room or operating room was significantly higher in Group B (87.8%) compared to Group A (75.4%) (P = 0.0025). At 22 weeks’ gestation, the rates were 66.5% in Group A and 85.7% in Group B (P = 0.1385), while at 23 weeks’ gestation, Group B had a significantly higher rate (88.1%) compared to Group A (78.1%) (P = 0.0188) (Table 2).

Comparative analysis of survival trajectories and mortality timing

More than 50% of deaths occurred within the first 7 postnatal days (postnatal day of death <7 days: Group A, 315/555 [56.8%]; Group B, 30/47 [63.8%]) (Table 3).

Kaplan–Meier plots up to 300 postnatal days showed higher survival in Group B compared to Group A in infants born at both 22–23 weeks’ gestation (22 weeks: P = 0.0298; 23 weeks: P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a, 1b). Kaplan–Meier plots up to 50 postnatal days also showed higher survival in Group B compared to Group A in infants born at 23 weeks (22 weeks: P = 0.1407; 23 weeks: P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1c, 1d). Furthermore, Group A showed a steep decline in survival within the first few postnatal days, whereas Group B demonstrated a higher initial survival rate. For infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, the time of rapid decline in survival (defined as the Point of Maximum Curvature in the Kaplan–Meier survival curve) occurred on postnatal day 3 in Group A and day 8 in Group B (P = 0.0695), indicating a delayed trend in Group B, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3, Fig. 1c). For infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, the time of rapid decline occurred on postnatal day 2 in Group A and day 8 in Group B (P < 0.0001), indicating a significantly later decline in Group B (Table 3, Fig. 1d).

Kaplan–Meier Survival Curves for Infants Born at 22–23 Weeks’ Gestation by Group: Overall Survival and Timing of Rapid Decline (a) Survival up to 300 postnatal days in infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, showing significantly higher survival in Group B compared to Group A (P = 0.0298). (b) Survival up to 300 postnatal days in infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, also showing significantly higher survival in Group B (P < 0.0001). (c) Survival up to 50 postnatal days in infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation; although Group B showed a higher survival trend, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.1407). The point of maximum curvature, representing the time of rapid decline in survival, occurred on postnatal day 3 in Group A and day 8 in Group B (P = 0.0695). (d) Survival up to 50 postnatal days in infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, with significantly better survival in Group B (P < 0.0001). The point of maximum curvature occurred on postnatal day 2 in Group A and day 8 in Group B (P < 0.0001). Group A is shown with a solid black line; Group B with a dashed red line.

Risk of mortality

Antenatal corticosteroid therapy was associated with a reduced risk of death (Hazard ratio [HR] 0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.49–0.69; P < 0.0001). Surfactant administration immediately after birth in the delivery or operating room was associated with an increased risk of death (HR 1.51; 95% CI, 1.24–1.83; P < 0.0001). Antenatal antibiotic therapy and cesarean delivery were not significantly associated with a reduced risk of death (Table 4).

Short-term and long-term outcomes of survivors

Among survivors, the median duration of invasive ventilation was 59.0 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 44.0–74.0), non-invasive ventilation was 39.0 days (IQR: 23.0–57.0), and total ventilatory support was 98.0 days (IQR: 83.0–119.0) (Supplementary Table 1). Among survivors, bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 256/298 (85.9%), intraventricular hemorrhage grade ≥3 in 105/316 (33.2%), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) stage ≥3 in 185/310 (59.7%), and ROP requiring treatment in 164/317 (51.7%). At corrected 18–24 months of age, growth restriction was noted in weight (67/177 [37.9%]), height (69/175 [39.4%]), and head circumference (78/155 [50.3%]). The need for rehabilitative support was observed in 89/180 (49.4%), language support in 23/180 (12.8%), and cerebral palsy in 35/180 (19.4%) (Supplementary Table 2).

At 3 years of age, growth restriction was observed in weight (6/108 [5.6%]), height (1/106 [0.9%]), and head circumference (20/96 [20.8%]). The need for rehabilitative support was reported in 47/112 (42.0%), language support in 39/112 (34.8%), and cerebral palsy in 25/112 (22.3%) (Supplementary Table 3).

Institutional characteristics stratified by survival rate (≥50% vs. <50%)

Institutional characteristics—such as institutional type (tertiary vs. secondary hospital), average annual number of preterm infants, number of neonatologists, minimum number of night-shift physicians, number of nurses, and number of advanced practice nurses—were found to be closely associated with institutional care level and the survival of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation (≥50% vs. <50%) (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, not only infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation but also those born at 23 weeks’ gestation showed significant differences in survival rates depending on the quality and experience of the medical team and the level of the neonatal unit. Moreover, in lower-level neonatal units, early neonatal deaths were more common, resulting in a different pattern of survival curves. The steepest decline in the Kaplan–Meier survival curve occurred earlier, indicating a poorer survival prognosis.

Proactive care includes active prenatal management—such as antenatal corticosteroid therapy, tocolytics, magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection, antibiotics for preterm PROM, and cesarean delivery for fetal indications—as well as active postnatal management, including neonatal resuscitation by skilled neonatologists, surfactant administration, and assisted ventilation10. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy was more common in higher-level neonatal units in this study, reflecting the proactive care provided in these settings, and was also associated with a reduced risk of death, consistent with previous findings11. Preterm infants at peri-viable gestation who are exposed to antenatal corticosteroid therapy receive more interventions at birth, have a lower incidence of pulmonary hypertension, and show improved survival to one year of life as well as better long-term outcomes12.

Surfactant administration immediately after birth was more common in higher-level neonatal units in this study, particularly among infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation. However, it was associated with an increased risk of death. This paradoxical finding may reflect a complex effect, possibly due to confounding by indication—where surfactant was administered immediately after birth because the infant’s condition was too unstable to delay treatment or to allow for NICU transfer.

According to a national survey from Japan, among infants born alive at 22 weeks’ gestation, 85% received proactive care at birth, while 98% of those born alive at 23 weeks’ gestation received proactive care. Survival rates at NICU discharge were 54% and 78% among infants born alive at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, respectively, and 63% and 80% among those who received postnatal life support at birth13. According to a survey of Korean neonatologists conducted by Professor Song (presented at the 23rd Congress of the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies), only 37% of neonatologists in Korea always provide proactive care for infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, whereas over 90% do so for those born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Thus, it appears that most hospitals in Korea provide proactive care for 23-week infants, while only some quaternary referral centers offer such care for 22-week infants. In this study, in lower-level neonatal units, intubation at birth was performed in 97.2% of infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, and surfactant was administered in 98.4% of cases. However, surfactant administration immediately after birth occurred in only 66.5% of cases, and antenatal corticosteroid therapy was given in just 55.6%. Based on these findings and the survey conducted by Professor Song, resuscitation at birth—such as intubation and surfactant administration—for infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation was likely not a reflection of truly proactive care, but rather a response shaped by the ethical and medicolegal circumstances faced by Korea, or individual neonatal units.

According to the Vermont Oxford Network, proactive care for infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation increased from 26% in 2007 to 58% in 2019, with survival rising from 5% to 17%14. Additionally, the proportion of these infants in hospitals with a level 3 or 4 designation within that network who received postnatal life support increased further, from 61.6% in 2020 to 73.7% in 202215. In the UK as well, survival-focused care for infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation increased from 11.3% to 38.4%, and as a result, survival to NICU discharge improved from 2.5% to 8.2%. This also indicates that the survival rate of infants born at the limit of viability, such as those at 22 weeks’ gestation, is not fixed and can be improved through the provision of high-quality proactive care16. Another study has reported that proactive care—such as antenatal corticosteroid therapy, active postnatal resuscitation, provision of assisted ventilation, and NICU admission—is associated with improved survival in infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation11. In Sweden, the improvement in survival is attributed to the policy of centralization of care introduced in 2014. Under this policy, mothers expected to deliver extremely preterm infants are transferred before birth to high-activity regions with more experienced medical teams and higher-level neonatal units, enabling the provision of high-quality proactive care to extremely preterm infants at the limit of viability. As a result, not only survival rates but also overall outcomes for these infants have improved17.

In the present study, compared with Group A (survival rate <50%), Group B (survival rate ≥50%) had a higher proportion classified into the low-level category (Level 1) based on equipment and resources. This suggests that, unlike in other countries where survival is influenced by NICU level based on equipment and resources18,19, survival is not necessarily improved by higher levels of equipment and resources. In Korea, NICU facilities are generally well-equipped regardless of whether the hospital is tertiary or secondary, which may explain this finding. Although the difference is statistically significant, we believe it is not strongly related to improved survival. In another KNN study20, the level of facility and resources also did not affect survival. Instead, in the present study, personnel—such as the number of neonatologists, the minimum number of night-shift physicians, the number of nurses, and the number of advanced practice nurses—were associated with institutional care level and the survival of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation.

According to a survey conducted in Japan, the median number of neonatologists in 145 NICUs that care for infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation is 8 (IQR: 5–9) 13. In contrast, Korea faces a severe shortage of neonatologists. The number of neonatologists is one of the most critical hospital factors influencing the quality of proactive care and the level of the neonatal unit. It is also the single most important independent factor contributing to the variation in mortality of preterm infants across centers in Korea20.

Studies continue to report that delivery of pregnant women at 22–26 weeks’ gestation in designated hospitals capable of providing high-quality perinatal and neonatal care improves the survival rates of peri-viable births, eliminates the risks associated with postnatal transfer, and leads to better outcomes21,22. In utero transfer to tertiary care centers with level 3 or 4 NICUs is a widely accepted practice, as it improves survival and reduces morbidity in peri-viable births23,24. However, few countries have established national guidelines for this practice16,25,26,27. Timely transfer of pregnant women at peri-viable gestation, facilitated by regionalization of perinatal care and a well-organized neonatal network, can further improve survival and outcomes for these infants. As demonstrated by studies from Korea and other countries, it cannot be overemphasized that the survival and morbidity of preterm infants at the limit of viability vary depending on the level of experience of the medical team and the availability of high-quality proactive care provided by higher-level neonatal units. Therefore, it is now truly time to establish national guidance regarding proactive care for infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation and to centralize perinatal care for deliveries at the earliest gestational ages.

This study has several limitations. Despite being based on a national cohort registry, the number of enrolled infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation was inevitably small due to the low incidence of births at that gestational age. Additionally, the number of patients in Group B, which represents higher-level neonatal units, was relatively small, leading to a significant imbalance compared to Group A. Another limitation is that data on antenatal antibiotic therapy were collected starting in 2018 resulting in a lack of data for earlier years. As with many multicenter cohort studies, it is difficult to accurately assess the extent of truly proactive care provided. Although interventions such as intubation and surfactant administration were performed, the rates of antenatal corticosteroid therapy and surfactant administration at birth were low. A survey of Korean neonatologists also showed that proactive care at 22 weeks’ gestation is uncommon, making it hard to gauge actual care levels.

In conclusion, the survival of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation was influenced by the quality and experience of the medical team. Early neonatal deaths were more frequently observed in lower-level units; thus, targeted efforts to reduce early mortality—such as timely in utero transfer to higher-level units—may further enhance survival outcomes. In addition, classifying institutions into higher- and lower-level groups according to the survival of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation (≥50% vs. <50%) provides a good reflection of the quality of neonatal care.

Methods

Study design and population

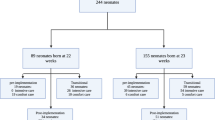

The KNN is a multicenter, nationwide prospective cohort registry that includes preterm infants from more than 70 participating centers, representing over 80% of preterm infants in Korea. A total of 919 infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2022 were enrolled (22 weeks: 21.3% [196/919], 23 weeks: 78.7% [723/919]).

Participating units were categorized into two groups: Group A (lower-level neonatal units with a survival rate for 22–23 weeks’ gestation <50%) and Group B (higher-level neonatal units with a survival rate for 22–23 weeks’ gestation ≥50%). Among the more than 70 KNN participating centers, data from 61 centers that enrolled at least one infant born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation during the study period were analyzed. Of these, 48 centers (785 infants) were assigned to Group A, and 13 centers (134 infants) were assigned to Group B. The enrollment criteria of the KNN included infants who were successfully resuscitated in the delivery room and admitted to the NICU. Therefore, infants who died in the delivery room were not enrolled in this study.

We compared clinical characteristics and the provision of proactive care between the two groups, including antenatal corticosteroid administration and resuscitation at birth (categorized by intensity: positive pressure ventilation, intubation, chest compressions, and epinephrine injection), as well as surfactant administration at birth. Clinical characteristics—such as sex, SGA infants, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, antenatal antibiotic administration, histologically confirmed maternal chorioamnionitis, PROM, cesarean delivery rate, maternal gestational diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and maternal age—were analyzed according to the two groups. We utilized data from the KNN pre-set registry; information on antenatal antibiotic administration has been recorded since 2018 and is available from that year onward. Mortality, timing of death, and the time (postnatal day) of rapid decline in survival were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves.

Among the 919 infants, 317 survivors were evaluated for short-term outcomes. These outcomes included the duration of ventilatory support (combined duration of invasive and non-invasive ventilation), bronchopulmonary dysplasia assessed at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age28, patent ductus arteriosus requiring surgical ligation29, intraventricular hemorrhage (grade ≥3), periventricular leukomalacia, culture-proven sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgery, ROP requiring treatment, and the need for assistance at discharge from the NICU (monitoring, oxygen, or tube feeding).

For long-term outcomes, 180 infants were followed up at a corrected age of 18–24 months, and 112 infants were followed up at 3 years of age. Long-term outcomes included growth restriction (weight <10th percentile, height <10th percentile, or head circumference <10th percentile), the need for rehabilitative or language support, blindness, the need for hearing aids, mental or motor developmental delays, and cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Function Classification System ≥ 2). Mental developmental delay was defined as: (1) a Mental Developmental Index < 70 on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) II; (2) a cognitive or language score < 70 on the BSID III; or, for infants who were not assessed using BSID II or III, (3) a cognition, language, or self-help score below the cutoff value on the Korean Developmental Screening Test (K-DST)30. Motor developmental delay was defined as: (1) a Psychomotor Developmental Index < 70 on the BSID II; (2) a motor score < 70 on the BSID III; or, for infants not assessed using BSID II or III, (3) a gross motor or fine motor score below the cutoff value on K-DST30.

Institutional characteristics included institutional type (tertiary vs. secondary hospital), level based on equipment and resources (1, 2, or 3), average annual number of preterm infants (<3, 3–4, >4), number of neonatologists (1, 2, ≥3), minimum number of night-shift physicians (≤1, ≥2), number of nurses (<20, 20–40, 40–60, >60), and number of advanced practice nurses (0, 1, ≥2). The level (1, 2, or 3) was determined based on nine items related to equipment and resources: availability of total parenteral nutrition, general pediatric surgery, pediatric thoracic surgery, nitric oxide therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy, dialysis treatment, echocardiography, other ultrasounds, and the capability of blood gas analysis within the unit. Each hospital was assigned one level based on the following classification scheme: a score of 1–5 as level 1, 6–7 as level 2, and 8–9 as level 320.

Statistical analysis

The t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was performed for continuous variables with a normal distribution and homogeneous variance, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables, as appropriate.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to derive the survival distribution function. The time point (in postnatal days) at which the survival rate declined most rapidly was analyzed using the Time of Maximum Hazard, defined as the point at which the Kaplan–Meier curve shows the steepest decline. To identify the point where the shape of the Kaplan–Meier survival curve changes most rapidly, we estimated the second derivative of the survival function using numerical approximation. The time point at which the absolute value of the second derivative was maximized was defined as the Point of Maximum Curvature (the time of rapid decline in survival), reflecting the most pronounced inflection in the survival trajectory. This analysis was used to detect potential structural changes in the event dynamics over time.

HRs and 95% CI using Cox proportional hazard regression were presented to evaluate the risks mortality. Data are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables and as numbers (%) for categorical variables, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and figures were generated using the R (version 4.3.1).

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in this study is not publicly available due to the policy of the Korea National Institute of Health. However, datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jeon, G. W. Need for national guidance regarding proactive care of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 68, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2024.01277 (2025).

Kim, J. K., Hwang, J. H., Lee, M. H., Chang, Y. S. & Park, W. S. Mortality rate-dependent variations in antenatal corticosteroid-associated outcomes in very low birth weight infants with 23–34 weeks of gestation: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 15, e0240168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240168 (2020).

Kim, J. K., Chang, Y. S., Sung, S. & Park, W. S. Mortality rate-dependent variations in the survival without major morbidities rate of extremely preterm infants. Sci. Rep. 9, 7371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43879-z (2019).

Park, J. H., Chang, Y. S., Sung, S. & Park, W. S. Mortality rate-dependent variations in the timing and causes of death in extremely preterm infants born at 23–24 weeks’ gestation. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 20, 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000001913 (2019).

Yang, M., Chang, Y. S., Ahn, S. Y., Sung, S. I. & Park, W. S. Neonatal intensive care quality level-dependent variations in the survival rate of infants with a birth weight of 500 g or less in korea: a nationwide cohort study. Neonatology 120, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1159/000527613 (2023).

Kim, J. K., Chang, Y. S., Sung, S., Ahn, S. Y. & Park, W. S. Trends in the incidence and associated factors of late-onset sepsis associated with improved survival in extremely preterm infants born at 23–26 weeks’ gestation: a retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 18, 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1130-y (2018).

Bell, E. F. et al. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices, and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013–2018. JAMA 327, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23580 (2022).

Arimitsu, T., Hatayama, K., Gaughwin, K. & Kusuda, S. Ethical considerations regarding the treatment of extremely preterm infants at the limit of viability: a comprehensive review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 184, 140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-025-05976-2 (2025).

Haga, M. et al. Changes in in-hospital survival and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely preterm infants: a retrospective study of a japanese tertiary center. J. Pediatr. 255, 166-174.e164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.11.024 (2023).

Obstetric Care consensus No. 6: periviable birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 130, e187–e199. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002352 (2017).

Silva, E. R., Shukla, V. V., Tindal, R., Carlo, W. A. & Travers, C. P. Association of active postnatal care with infant survival among periviable infants in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2250593. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50593 (2023).

Seasely, A. R. et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes at periviable gestation throughout delivery admission. Am. J. Perinatol. 41, e2952–e2958. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1776347 (2024).

Isayama, T. et al. Survival and unique clinical practices of extremely preterm infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation in Japan: a national survey. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 110, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2023-326355 (2024).

Rysavy, M. A. et al. An immature science: intensive care for infants born at ≤23 weeks of gestation. J Pediatr 233, 16-25.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.006 (2021).

Edwards, E. M., Ehret, D. E. Y., Soll, R. F. & Horbar, J. D. Survival of infants born at 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation receiving care in the NICU: 2020–2022. Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-065963 (2024).

Smith, L. K. et al. Effect of national guidance on survival for babies born at 22 weeks’ gestation in England and Wales: population based cohort study. BMJ Med. 2, e000579. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmed-2023-000579 (2023).

Christiansson, Y., Moberg, M., Rakow, A. & Stjernholm, Y. V. Increased Survival concomitant with unchanged morbidity and cognitive disability among infants born at the limit of viability before 24 gestational weeks in 2009–2019. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124048 (2023).

Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics 130, 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1999 (2012).

Serenius, F., Blennow, M., Maršál, K., Sjörs, G. & Källen, K. Intensity of perinatal care for extremely preterm infants: outcomes at 2.5 years. Pediatrics 135, e1163-1172. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2988 (2015).

Lee, M. H., Lee, J. H. & Chang, Y. S. Neonatologist staffing is related to the inter-hospital variation of risk-adjusted mortality of very low birth weight infants in Korea. Sci. Rep. 14, 20959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69680-1 (2024).

Rysavy, M. A. Time to centralise perinatal care for deliveries at the earliest gestations?. Acta Paediatr 114, 473–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.17555 (2025).

Gadsbøll, C. et al. Centralisation of extremely preterm births and decreased early postnatal mortality in Sweden, 2004–2007 versus 2014–2016. Acta Paediatr 114, 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.17429 (2025).

Cho, I. Y., Lee, H. M., Kim, S. Y. & Kim, E. S. Impact of outborn/inborn birth status of infants born at <29 weeks of gestation on neurodevelopmental impairment: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811718 (2022).

Walther, F. et al. Impact of regionalisation and case-volume on neonatal and perinatal mortality: an umbrella review. BMJ Open 10, e037135. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037135 (2020).

Nishida, H. & Ishizuka, Y. Survival rate of extremely low birthweight infants and its effect on the amendment of the Eugenic Protection Act in Japan. Acta Paediatr. Jpn. 34, 612–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200x.1992.tb01020.x (1992).

Domellöf, M. & Pettersson, K. Guidelines for threatening premature birth will provide better and more equal care. Lakartidningen 114 (2017).

Abdel-Latif, M. E., Kecskés, Z. & Bajuk, B. Actuarial day-by-day survival rates of preterm infants admitted to neonatal intensive care in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 98, F212-217. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2011.210856 (2013).

Jeon, G. W., Oh, M. & Chang, Y. S. Increased bronchopulmonary dysplasia along with decreased mortality in extremely preterm infants. Sci. Rep. 15, 8720. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93466-8 (2025).

Yang, M. et al. Conservative management of patent ductus arteriosus is feasible in the peri-viable infants at 22–25 gestational weeks. Biomedicines https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11010078 (2022).

Jeon, G. W., Oh, M., Lee, J., Jun, Y. H. & Chang, Y. S. Comparison of definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia to reflect the long-term outcomes of extremely preterm infants. Sci. Rep. 12, 18095. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22920-8 (2022).

Funding

This study was supported by the Korea National Institute of Health research project (2025-ER0601-00#). The funding organization played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study concept and design: G.W.J., M.O., and Y.S.C. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: G.W.J., M.O., M.H.L., and Y.S.C. Drafting the manuscript: G.W.J., M.O., and Y.S.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: G.W.J., M.O., M.H.L., and Y.S.C. Statistical analysis: M.O., and M.H.L Obtained funding: Y.S.C. Study supervision: G.W.J., M.O., and Y.S.C. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The institutional review board of each participating center, including Samsung Medical Center (IRB number 2013-03-002) and Inha University Hospital (IRB number 2016-03-006), approved the KNN data registry for both the admission and follow-up phases. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all enrolled infants. This study was approved by the KNN Ethics Committee, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the approved study protocol (protocol number 2024-007).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, G.W., Oh, M., Lee, M.H. et al. Variations in survival outcomes of infants born at 22–23 weeks’ gestation by neonatal intensive care quality level in Korea. Sci Rep 16, 248 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28428-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28428-1