Abstract

Little is known about the association between physical activity and the risk of pre-sarcopenic obesity (pre-SO) among adolescents. Hence, this study aimed to examine the association between physical activity and pre-SO in a sample of 2143 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years from Yinchuan, China. The pre-SO was defined by three criteria: low skeletal muscle mass adjusted by weight (SMM/W) combined with body mass index (BMI), fat mass percentage (FMP), and waist circumference (WC). After adjusting for age, smoking, drinking, sleep time, and high-fat food consumption, participants with high physical activity (HPA) had a lower risk of pre-SO compared to those with low physical activity (LPA) according to the obesity criteria of FMP (OR 0.63, 95% CI, 0.48–0.83, P < 0.05), and WC (OR 0.71, 95% CI, 0.52–0.96, P < 0.05). Additionally, restricted cubic spline models showed a linear dose-response association between total physical activity (TPA) and pre-SO no matter what obesity criteria were adopted (all P overall trend < 0.05, all P non-linear > 0.50). Subgroup analyses revealed that individuals with higher TPA levels exhibited a decreased risk of pre-SO in boys according to the obesity criteria of FMP, and WC. In conclusion, HPA is associated with a reduced risk of pre-SO in adolescents, especially among boys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcopenic obesity (SO) is defined as the concurrent presence of sarcopenia and obesity, and is initially proposed among the elderly population1. However, the prevalence of SO among adolescents has also drawn widespread attention in recent years, particularly in the context of escalating obesity rates and sedentary lifestyle2. Results from a system review shows that the prevalence of SO ranged between 5.66% and 69.7% in girls, with a range from 7.2% to 81.3% in boys3. Importantly, compared to individuals who only have sarcopenia or obesity, those with SO face more severe health risks4. It can cause higher risks of metabolic disturbances, a greater incidence of cardiovascular disease and increased mortality5,6,7, thereby posing a significant threat to the long-term health of adolescents.

Pre-sarcopenic obesity (pre-SO), as a critical stage from a healthy state to sarcopenic obesity, is an important period for clinical prevention and treatment. However, there are no effective drugs for treating SO8. The SO and lack of physical activity are fast becoming a concern among children and adolescents. The exercise intervention is regarded as a means with both therapeutic and preventive potential9. Physical activity helps reduce fat accumulation and prevent low muscle mass, which is of great significance for preventing metabolic diseases such as sarcopenic obesity. Data from a survey of community-dwelling older adults in Korea revealed a significant association between high physical activity and a reduced risk of SO10. Choi et al. involved 2071 participants and found that vigorous physical activity may be beneficial for reducing the prevalence of SO5. A randomized controlled trial showed that implementing exercise intervention measures for the elderly with SO could significantly improve their physical conditions9.

Nevertheless, current studies have primarily focused on middle-aged and elderly populations, investigations from adolescents have predominantly centered on the associations between physical activity and sarcopenia or obesity. For example, A cross-sectional study revealed that moderate to high physical activities significantly increase muscle mass among adolescents11. Oshita et al. found that physical activity was significantly positively associated with skeletal muscle mass index among female university students from Japan12. A study from school-going 13 year old multi-ethnic adolescents from population representative samples in Malaysia showed that high physical activity scores were associated with the decreased precursor risk factors of obesity13. In summary, there remains a significant gap in the relationship between physical activity and sarcopenic obesity or pre-SO among adolescents.

Therefore, this study utilizes cross-sectional data from Yinchuan, Ningxia, China, to investigate the association between physical activity and pre-sarcopenic obesity (pre-SO) in adolescents. It aims to provide a theoretical basis for the prevention and management of sarcopenic obesity in adolescents and promote the in-depth application of exercise-medicine integration in youth health initiatives.

Methods

Study population

This study was a series of cross-sectional studies conducted in Yinchuan, China, from October 2017 to September 2020. Stratified random cluster sampling was used to select three junior high schools and three senior high schools as samples. After stratification by grade, 13 junior high school classes and 32 senior high school classes were randomly selected. Inclusion criteria: (1) Willing participation in the study and ability to provide required information; (2) General good health with normal physical development, capable of engaging in various physical activities. Exclusion criteria: (1) Age outside the range of 12 to 18 years; (2) Incomplete physical activity data; (3) Presence of current or recent cardiovascular disease, hepatic, renal, or thyroid dysfunction, or ongoing treatment with steroid hormones or thyroid hormone. Ultimately, 2143 subjects were included.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Ningxia Medical University (Approval ID: 2016 − 123). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians, confirming that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Assessment of physical activity levels

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) has been validated as an effective tool for assessing the physical activity levels of adolescents14. This study utilized the IPAQ - Short Form, which consists of seven items. Participants were asked to retrospectively report the duration and frequency of their engagement in three types of physical activities during the previous week: light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA), and vigorous physical activity (VPA). Physical activity levels were expressed in metabolic equivalents (METs), with the METs values for LPA, MPA, and VPA being 3.3, 4.0, and 8.015, respectively16.

The participants were classified into three levels of physical activity based on the IPAQ guidelines: High physical activity (meeting either of the following two criteria): (1) 7 d of walking or moderate or vigorous intensity activities totaling ≥ 3000 MET-min/week; (2) vigorous intensity activity on ≥ 3 d with ≥ 1500 MET-min/week; Moderate activity (any one of the following three criteria) : (1) ≥ 5 d of walking or moderate or vigorous intensity activities totaling ≥ 600 MET-min/week; (2) ≥ 5 d of 30 min of moderate intensity and/or walking per day; (3) ≥ 3 d of 20 min of vigorous activity per day; And low activity (not enough to meet moderate or high activity criteria)17.

Anthropometric measurements

All anthropometric measurements were performed by trained staff using standardized procedures. Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured twice, and the mean value was used for analysis. Measurements were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm or 0.1 kg. If the two measurements differed by more than 0.5 cm or 0.5 kg, a third measurement was taken to ensure accuracy and minimize technical error18. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Body composition analysis and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) were performed using Inbody 370 (Biospace Co., Seoul, Korea), and the skeletal muscle mass (SMM) and fat mass percentage (FMP) were directly read. FMP has always been regarded as an ideal indicator for evaluating body composition. However, BIA is inevitably limited by factors such as the degree of obesity and age, and there may be problems of underestimating or overestimating FMP19

Definition

According to the study by Xu et al.20 the definition of pre-SO combined the low skeletal muscle mass adjusted by weight (SMM/W) and obesity criteria. Low muscle mass was characterized by SMM/W < 1 standard deviation below sex-specific mean values. To ensure the robustness of the criteria, obesity was assessed using three screening standards for adolescents: body mass index (BMI) ≥ 28 kg/m²21; fat mass percentage (FMP) > 20% for boys and FMP > 25% for girls22,23; Waist circumference (WC) ≥ the 90th percentile in each sex and age group24

Covariates

Based on previous research25,26,27, we examined potential confounding factors among demographic characteristics and health-related factors, and ultimately selected age, gender, smoking, drinking status, high-fat food consumption and sleep time as covariates. Smoking was defined as having smoked or attempted to smoke at least once during the past month. Drinking was defined as having consumed alcohol or attempted to consume it during the same period. Sleep time was calculated based on the participants reported going to bed at night and waking up in the morning on school days. High-fat food consumption was defined based on high-fat dietary behaviors reported during the past week, including fried foods, high-sugar foods (such as cakes and chocolates), high-sugar beverages, and poultry meat consumed more than three times per week. If any one of these criteria was met, the individual was classified as having a high-fat diet.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered using EpiData 3.1 software, and statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and R (version 4.2.2). Normally distributed continuous variables were described as mean (standard) deviation, non-normally distributed data were presented as median (interquartile range), and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Differences between groups were compared using t-tests, chi-square tests, and rank-sum tests. After adjusting for covariates including age, gender, smoking, drinking status, and sleep time, a binary logistic regression model was employed to analyze the relationship between physical activity levels and pre-SO. The dose-response relationship between physical activity levels and pre-SO was modeled using restricted cubic splines (RCS), followed by stratified analysis. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The study included 2,143 participants (1,292 boys and 851 girls). The mean age of participants was 15.00 years. The prevalence of pre-SO based on different criteria; high BMI, high FMP, and high WC were 176 (8.21%), 397 (18.49%), and 315 (14.70%), respectively. Compared to individuals non-pre-SO, those with pre-SO were younger, had a higher proportion of engaging in MPA, and higher proportion of girls (P < 0.05). The TPA was significantly higher in the non-pre-SO group than in the pre-SO group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the differences in the comparison of smoking, drinking, sleep time, physical activity between pre-SO and non-pre-SO adolescents were statistically significant (all P < 0.05).

Association between physical activity and pre-sarcopenic obesity

ORs of different physical activity level groups were examined using logistic regression analysis (Table 2). TPA was significantly associated with pre-SO in the three obesity criteria. Specifically, the risk of pre-SO decreased by 24%, 27% and 24% for each 1 METs-min/week increase in total physical activity, respectively. In the fully adjusted model, when obesity was assessed using FMP, participants who engaged in high physical activity (HPA) exhibited a significantly lower risk of pre-SO compared to those with low physical activity (LPA) (OR = 0.63, 95%CI, 0.48–0.83, P < 0.05). When obesity was assessed using WC, the results indicated a reduced risk of pre-SO for individuals engaging in HPA compared to those with LPA (OR = 0.71, 95%CI, 0.52–0.96, P < 0.05).

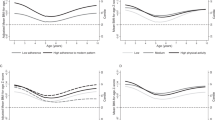

Dose-response relationships between the total physical activity and pre-sarcopenic obesity

The dose-response relationships between the total physical activity and pre-SO using by the restricted cubic splines (RCS) regression models are presented in Fig. 1. After adjusted for age, smoking, drinking, sleep time and high-fat food consumption, the results demonstrated a linear dose-response association between total physical activity and pre-SO no matter what obesity criteria were adopted (all P overall trend < 0.05, all P non-linear > 0.50). RCS analysis results also indicated that with increased of TPA level, the risk of pre-SO was significantly lower in which adiposity status assessed by BMI, FMP and WC.

Dose-response relationships between the total physical activity levels and pre-SO. (a–c) unadjusted model; (d–f) adjusted for age, smoking, drinking, sleep time, and high-fat food consumption. (a,d) Pre-SO was assessed by low SMM/W + high body mass index; (b,e) Assessed by low SMM/W + high fat mass percentage; (c,f) Assessed by low SMM/W + high waist circumference.

Subgroup analyses

The results of the stratified analyses based on age, smoking, drinking, sleep time, and high-fat food consumption are shown in Fig. 2. Results indicated that a negative correlation between TPA and pre-SO across various subgroups. There was a significant interaction between the TPA levels and stratified variables based on sex in which pre-SO status assessed by low SMM/W combined with obesity criteria of FMP, and WC (P interaction < 0.05). Specifically, individuals with higher TPA levels exhibited a decreased risk of pre-SO in boys, but not remarkable in girls. There was no significant interaction between the total physical activity levels and other stratified variables.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between physical activity with the pre-SO in adolescents. The definition of pre-SO based on three criteria: low SMM/W combined with obesity criteria of BMI, FMP and WC. Our results indicated that TPA was significantly associated with pre-SO in the three obesity criteria. After adjusted for age, smoking, drinking, sleep time and high-fat food consumption, participants with HPA had a significantly lower risk of pre-SO than those with the LPA did. Additionally, we found a linear dose-response relationship between TPA and the risk of pre-SO no matter what obesity criteria were adopted.

The SO was previously thought to primarily affect the older, emerging evidence points that SO can also manifest in adolescents, particularly in the context of climbing obesity rates and physical inactivity2. The prevalence of SO in adolescents has been reported to 7.5 to 33.3% according to previous studies28,29. This wide range is because of the different methods employed to define SO and the varying cutoff points applied3. Although the definition of SO different between studies, all of the results indicate that the burden of adolescent SO is substantial. In this study, we found the prevalence of pre-SO included different criteria; high BMI, high FMP, and high WC were 8.21%, 18.49%, and 14.70%, respectively.

Regular physical activity supports weight management, enhances physical function, and slows the muscle loss linked to aging30. Although the benefits of physical activity for combating obesity and sarcopenia have been widely reported, most studies focus on elderly populations. Research examining the effects of physical activity on SO in adolescents remains scarce. Our findings revealed a decline in the risk of pre-SO with rising levels of TPA. A cross-sectional study in post-liver transplantation (LT) children aged between 6 and 18 years showed that lower moderate-to-high physical activity was associated with a high prevalence of sarcopenia in children31. A study by Hao et al. revealed that the skeletal muscle mass index was positively correlated with physical activity, particularly in moderate-to-high intensity activities11. In our study, although individuals with HPA had a lower risk of pre-SO compared to those with LPA, no significant improvement effect of MPA on adolescent sarcopenic obesity was observed. The primary reason may be that the assessment of physical activity was based on the retrospective IPAQ questionnaire, which may subject to bias.

Exercise serves as an effective intervention for Pre-SO. Studies have shown that exercise can upregulate anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, thereby counteracting the inhibitory effect of TNF-α on muscle protein synthesis and alleviating inflammation and oxidative stress in skeletal muscle32,33. Moreover, exercise stimulates the production of IGF-1, a key regulator of muscle maintenance and hypertrophy34. It also activates intramuscular anabolic signaling pathways, including the PI3-K/Akt/mTOR axis, enhancing protein synthesis, increasing lean mass, elevating basal metabolic rate, and ultimately reducing adiposity35. These mechanisms support the beneficial role of physical activity in decreasing the risk of pre-sarcopenic obesity, as observed in our study.

This research focuses on the adolescent population and investigates the preclinical stage of SO, aiming to provide evidence for early prevention and treatment strategies of sarcopenic obesity in adolescents. For the diagnosis of pre-sarcopenic obesity, we employed three criteria to enhance the robustness of the results. However, this study also has limitations. Firstly, due to the cross-sectional study design, this study cannot establish causality between physical activity and pre-SO. Secondly, this study utilized the IPAQ, which is a retrospective survey questionnaire, potentially leading to information bias. Thirdly, the study sample may not be representative of the entire adolescent population, as it was limited to participants from a single city in Northwest China. Moreover, the physical activity data were collected based on self-reporting, which may introduce deviations from the actual situation.

In conclusion, we found that a high physical activity level was associated with a lower prevalence of pre-SO in adolescents.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Donini, L. M. et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Obes. Facts. 15, 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521241 (2022).

Gündüz, B., Çamurdan, A. D., Yildiz, M., Aksakal, F. N. B. & Ünsal, E. N. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sarcopenic obesity among children between 6 and 10 years of age: a prospective study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 184 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-025-06067-y (2025).

Zembura, M. & Matusik, P. Sarcopenic obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 914740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.914740 (2022).

Hsu, K. J., Liao, C. D., Tsai, M. W. & Chen, C. N. Effects of Exercise and Nutritional Intervention on Body Composition, Metabolic Health, and Physical Performance in Adults with Sarcopenic Obesity: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092163 (2019).

Choi, K. M. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Korean J. Intern. Med. 31, 1054–1060. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.193 (2016).

Ghiotto, L., Muollo, V., Tatangelo, T., Schena, F. & Rossi, A. P. Exercise and physical performance in older adults with sarcopenic obesity: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 913953. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.913953 (2022).

Kim, J. H., Cho, J. J. & Park, Y. S. Relationship between sarcopenic obesity and cardiovascular disease risk as estimated by the Framingham risk score. J. Korean Med. Sci. 30, 264–271. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.3.264 (2015).

Goisser, S. et al. Sarcopenic obesity and complex interventions with nutrition and exercise in community-dwelling older persons–a narrative review. Clin. Interv. Aging. 10, 1267–1282. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S82454 (2015).

Hita-Contreras, F. et al. Effect of exercise alone or combined with dietary supplements on anthropometric and physical performance measures in community-dwelling elderly people with sarcopenic obesity: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas 116, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.07.007 (2018).

Ryu, M. et al. Association of physical activity with sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in community-dwelling older adults: the fourth Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Age Ageing. 42, 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft063 (2013).

Hao, G. et al. Associations between muscle mass, physical activity and dietary behaviour in adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 14 https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12471 (2019).

Oshita, K., Ishihara, Y., Seike, K. & Myotsuzono, R. Associations of body composition with physical activity, nutritional intake status, and chronotype among female university students in Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 43, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-024-00360-9 (2024).

Su, T. T. et al. Association between self-reported physical activity and indicators of body composition in Malaysian adolescents. Prev. Med. 67, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.001 (2014).

Pols, M. A., Peeters, P. H., Kemper, H. C. & Grobbee, D. E. Methodological aspects of physical activity assessment in epidemiological studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 14, 63–70. (1998).

Zhai, X. et al. Mediating effect of perceived stress on the association between physical activity and sleep quality among Chinese college students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010289 (2021).

Lynch, L., McCarron, M., McCallion, P. & Burke, E. To identify and compare activpal objectively measured activity levels with Self-Reported activity from the international physical activity questionnaire in older adults with intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabilities: JARID. 38, e13327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13327 (2025).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 35, 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.Mss.0000078924.61453.Fb (2003).

Xu, Y. et al. Role of hyperglycaemia in the relationship between serum osteocalcin levels and relative skeletal muscle index. Clin. Nutr. 38, 2704–2711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.025 (2019).

Eisenmann, J. C., Heelan, K. A. & Welk, G. J. Assessing body composition among 3- to 8-year-old children: anthropometry, BIA, and DXA. Obes. Res. 12, 1633–1640. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.203 (2004).

Xu, Y. et al. Neck circumference as a potential indicator of pre-sarcopenic obesity in a cohort of community-based individuals. Clin. Nutr. 43, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2023.11.006 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Body mass index growth curves for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years. Chin. J. Pediatr. 47, 493–498. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2009.07.004 (2009). (in Chinese).

Ji, C. Y. Children and juvenile hygiene (7 ed.) 126–131 (Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, (in Chinese) (2012).

Lu, X. L. Comparison of cardiometabolic indexes between recessive obesity and normal weight middle school students in Jiaozuo City. Chin. J. School Health. 39, 429–431. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2018.03.031 (2018). (in Chinese).

Ma, G. S. et al. Waist circumference reference values for screening cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 31, 609–615. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2010.06.003 (2010). (in Chinese).

Hayes, J. F. et al. Sleep patterns and quality are associated with severity of obesity and Weight-Related behaviors in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Child. Obes. (Print). 14, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2017.0148 (2018).

Moon, J. H., Kong, M. H. & Kim, H. J. Low muscle mass and depressed mood in Korean adolescents: a Cross-Sectional analysis of the fourth and fifth Korea National health and nutrition examination surveys. J. Korean Med. Sci. 33, e320. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e320 (2018).

Palacio-Agüero, A. & Díaz-Torrente, X. Quintiliano scarpelli Dourado, D. Relative handgrip strength, nutritional status and abdominal obesity in Chilean adolescents. PloS One. 15, e0234316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234316 (2020).

Pacifico, L. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with low skeletal muscle mass in Overweight/Obese youths. Front. Pead. 8, 158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00158 (2020).

Steffl, M., Chrudimsky, J. & Tufano, J. J. Using relative handgrip strength to identify children at risk of sarcopenic obesity. PloS One. 12, e0177006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177006 (2017).

Choi, S. et al. The impact of the physical activity level on sarcopenic obesity in Community-Dwelling older adults. Healthc. (Basel Switzerland). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030349 (2024).

Ooi, P. H. et al. Deficits in muscle strength and physical performance influence physical activity in sarcopenic children after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 26, 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25720 (2020).

Guo, A., Li, K. & Xiao, Q. Sarcopenic obesity: myokines as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets? Exp. Gerontol. 139, 111022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2020.111022 (2020).

Park, J., Bae, J. & Lee, J. Complex exercise improves Anti-Inflammatory and anabolic effects in Osteoarthritis-Induced sarcopenia in elderly women. Healthc. (Basel Switzerland). 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060711 (2021).

Annibalini, G. et al. Concurrent aerobic and resistance training has anti-inflammatory effects and increases both plasma and leukocyte levels of IGF-1 in late middle-aged type 2 diabetic patients. Oxidative Med. Cell. longevity 3937842 https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3937842 (2017).

Leuchtmann, A. B., Adak, V., Dilbaz, S. & Handschin, C. The role of the skeletal muscle secretome in mediating endurance and resistance training adaptations. Front. Physiol. 12, 709807. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.709807 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants for their contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W. Ding and Y. Xu designed the research and helped write the manuscript; W. Ding and Y. Xu contributed to data extraction and provided feedback on the report. And all authors contributed to writing, reviewing, and approving the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Shi, L., Chen, L. et al. Physical activity is associated with a lower risk of pre-sarcopenic obesity in adolescents: evidence from Northwest China. Sci Rep 15, 44712 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28449-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28449-w