Abstract

Biocompatible scaffolds play a crucial role in creating 3D in vitro models for precision medicine. Understanding liquid transport dynamics is essential for ensuring timely delivery of nutrients, drugs or imaging agents to cells embedded within the scaffold. Therefore, it is imperative to thoroughly characterise the physical properties of these scaffolds. In this study, we leverage nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine the diffusivity and flow-driven perfusion properties of commonly used cryogels and hydrogels. We used deuterium oxide (i.e. heavy water) as a contrast agent to monitor the reduction in proton concentration from water within the scaffolds due to molecular motion. By analysing pixel intensity in MRI images, we extract information on the diffusion speed and liquid passage efficacy of these materials. This approach allowed us to investigate passive water diffusion in a carboxymethyl cellulose cryogel and polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel. The diffusion rates differed by 50% between the two scaffolds by direct comparison of their diffusion coefficients. Furthermore, we measured their flow-driven perfusion properties in a PDMS microfluidic chip.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models is a central goal in tissue engineering, as these systems provide physiologically relevant environments that support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation1,2,3. Beyond their biological relevance, 3D in vitro models offer a valuable alternative to animal testing and hold promise for applications in personalised and regenerative medicine4. Among the available materials, hydrogels and cryogels have emerged as leading candidates due to their high water content, tunable mechanical properties, and proven biocompatibility5,6.

Hydrogels are used as a support material for cellular proliferation because they replicate the characteristics of the extracellular matrix (ECM)7,8. Encapsulating cells within hydrogels confers several beneficial properties, including high water content and mechanical adjustability to generate specific architectures9,10. However, producing big pores (from hundreds of nanometers to a few micrometers) in a reproducible way remains a challenge5,11,12,13,14. The pore size has a direct impact on the elimination of waste products, appropriate oxygen diffusion, nutrient delivery and vessel formation in tissues14,15,16,17. Moreover, these limitations hamper the possibility of delivering external solutions or substances into cells, such as drugs or contrast agents for imaging, in a fast and controlled manner.

Alternatively, cryogels adeptly address several of the drawbacks and limitations of hydrogel scaffolds18. One can fabricate cryogels with materials that match the properties of the corresponding target tissue and have characteristic big (from a few to hundreds of micrometres) micropore sizes with sponge-like appearance and high pore interconnectivity and water content19,20. These features make them particularly attractive to techniques requiring fast liquid perfusion into scaffolds21,22.

Diffusion (Eppendorf) and flow-driven perfusion process (4-well microfluidic chip) of biocompatible scaffolds using a pre-clinical \(3\,T\) MRI scanner. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental setup consisting of the scaffold under study (hydrogel or cryogel), heavy water, a \(0.5\,mL\) Eppendorf, a 4-well microfluidic platform, and a \(3\,T\) MRI scanner. For diffusion studies, we submerged the scaffolds (origin of the water proton signal) into the Eppendorf containing deuterium oxide (absence of signal). For flow-driven perfusion studies, we enclosed the scaffolds into the microfluidic chip wells and injected deuterium oxide from the microfluidic features of this. (B) Proton MRI coronal (green), sagittal (orange), and axial (blue) plane images of the 4-well microfluidic device filled with water using a T\(_1\)-FLASH MRI sequence. The planes are directly related to the microfluidic platform represented in panel (A).

In the biomaterials research field, studying liquid diffusion and perfusion is of paramount importance23. Understanding how fluids flow throughout biomaterials is crucial for optimising the design of tissue-engineered constructs, drug delivery systems or hyperpolarised molecular imaging24,25. Nowadays, many techniques are available to analyse pore size and distribution, such as NMR relaxometry26, mercury intrusion porosimetry27, micro-computed tomography28,29,30,31, optical coherence tomography (OCT)32, and ultrasound33. These methodologies are useful to examine microstructures but lack the capability to assess and evaluate liquid penetration efficiency through a porous material. For example, confocal fluorescence microscopy may be used to study the perfusion into a shallow external layer of the biomaterials34,35,36 but struggles to penetrate deep into materials, making it less effective for three-dimensional analysis. Moreover, the size and structure of the fluorescent particles play a crucial role in determining diffusion rate constants, while also impacting the chemical and structural properties of the studied object37. Furthermore, such particles can suffer from photobleaching (i.e., destruction of fluorescence activity) after repeated measurements38,39. In contrast, OCT provides micron-scale resolution ideal for surface imaging but is limited by shallow penetration depth, and ultrasound is real-time and portable, suitable for soft tissue imaging, but has lower resolution and is operator-dependent.

Modern medicine extensively uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to accurately and non-invasively characterise the properties of multiple biological materials40,41,42,43,44. A pivotal advancement in MRI technology is the use of contrast agents, which enhance the visibility of specific tissues or structures45,46,47.For example, gadolinium-based contrast agents are widely used in MRI to enhance soft tissue contrast and assess perfusion. In the field of biomaterials, researchers employed gadolinium to investigate the diffusion properties of hydrogels embedded with fibroblasts23.

Among alternative contrast agents, deuterium oxide (D\(_2\)O, or heavy water) offers a unique advantage for MRI studies of water dynamics. D\(_2\)O and H\(_2\)O possess nearly identical physicochemical properties, differing mainly in nuclear spin, mass, and gyromagnetic ratio. Crucially, deuterium does not produce signal in conventional \(^1\)H MRI; thus, replacing H\(_2\)O with D\(_2\)O leads to a quantifiable reduction in the \(^1\)H signal, which is linearly proportional to the local D\(_2\)O concentration48,49,50,51. This approach provides a simple, quantitative and physiologically inert method to monitor water exchange, diffusion and perfusion in biological systems.

In contrast, gadolinium-based contrast agents affect T\(_1\) and T\(_2\) relaxation times in a nonlinear and environment-dependent manner, with performance strongly influenced by local susceptibility effects, field strength, and pulse sequence parameters. These limitations can complicate interpretation in heterogeneous or low-perfusion regions and pose reproducibility challenges.

In this study, we apply D\(_2\)O-enhanced MRI to investigate both passive diffusion and active flow-driven perfusion in two biocompatible scaffolds: cryogels based on carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and hydrogels based on polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) (Fig. 1). By tracking the progressive loss of \(^1\)H signal as D\(_2\)O replaced water, we non-destructively quantified the scaffold’s transport properties. This strategy, compatible with repeated measurements and free from chemical reactivity, offers a robust platform for studying water dynamics in tissue-engineered systems using accessible MRI instrumentation.

To demonstrate the applicability and versatility of this approach, we first use it to investigate passive diffusion within scaffolds immersed in an enclosed D\(_2\)O environment (Fig. 1A, left). In this configuration, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is also used to quantify the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of water both inside and outside the scaffold. Subsequently, we apply the same strategy to study active liquid transport through the scaffolds using custom-designed microfluidic systems (Fig. 1A(right),B). Furthermore, both studies proved to be highly effective and reproducible (non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with p value of 0.029 among replicates) within this easy-to-handle system setup. With these results, we expect to open a new approach for diffusion and flow-driven perfusion studies using MRI technology.

Materials and methods

CMC cryogel fabrication

A prepolymer solution containing a desired percentage of 90 kD carboxymethylcellulose was dissolved in MilliQ water under magnetic stirring for 1 h at \(45^{\circ }C\). We prepared the crosslinking reagents as 0.5 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) hydrate buffer adjusted at pH 5.5 with NaOH, 5% adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH) in MilliQ water, and 5.22 mM N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N’- ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) dissolved in MilliQ water. Next, 1 ml of the prepolymer, 50 mM of MES buffer, 1.83 mM of ADH, and 18.9 \(\upmu\)M of EDC were mixed. Shaking was critical to avoid early crosslinking before freezing the sample. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) circular moulds (chambers measuring 2 mm in height and 10 mm in diameter, enclosed between two square \(24\times 24\) mm cover glasses) were filled with the final prepolymer solution. Then, we stored the samples at \(-20^{\circ }C\) for 24 h. Finally, the cryogels were thawed at room temperature, and the scaffolds were subsequently created by perforating the polymer using a 5 mm biopsy punch. The process finished by autoclaving the scaffolds for sterilisation.

10% PEGDA hydrogel fabrication

A prepolymer solution containing 10% PEGDA (poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, Mn 575 g/mol) and 1% irgacure D-2959 (2-Hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone), all w/v, was dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at \(65^{\circ }\)C for 1 h, filtered and crosslinked under UV light using a MJBA mask aligner (SUSS MicroTech) (power density of 25 \(mW\, cm^{-2}\)). We obtained disc-like samples of 10 mm in diameter by exposing the prepolymer solutions for 500 s. After UV exposure, the unreacted prepolymer solution was washed with PBS and we left the resulting samples to reach equilibrium swelling for 24 h at \(4^{\circ }\)C. Before the MRI measurement, hydrogels were punched to the desired final diameter (5 mm).

Microfluidic chips fabrication

Molds with microfluidic channels and features were fabricated using standard photolithography methods using silicon wafers (4” n-type <111>, MicroChemicals GmbH), photoresist (SU-8 2100, KAYAKU Advanced Materials, Inc.) and UV light52,53. The wafer was silanised by vapour exposure of 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl-trichlorosilane (PFOTS, 97%, Merck). Then, standard soft lithography with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was used to produce the microfluidic devices from the patterned SU-8 (MicroChemicals GmbH) molds. The PDMS prepolymer was prepared (Sylgard 184, Ellsworth Adhesives) in a 10:1 ratio (elastomer base: curing agent, w/w). The chips consisted of two PDMS layers with the microfluidic channels serving two functions: (1) distributing the liquid (in the lower 5 mm thick layer) through four distinct channels that collectively distribute the sample into each well, and (2) removing excess liquid during injection (in the top 5 mm thick layer, unused in the results shown in this work). The chambers and inlet and outlet ports were punched in the corresponding PDMS layers using 6 mm and 1.2 mm biopsy punches, respectively. The two PDMS layers and a glass slide (\(75\times 25\) mm Corning) were activated and bonded together using O\(_2\) plasma in all the components mentioned before (PDC-002, Harrick Plasma). The overall dimensions of the microfluidic chip were 38 \(\times\) 75 \(\times\) 11 mm (WxLxH). We fabricated the device from 2 \(\times\) 5 mm thick layers of PDMS and a 1 mm thick microscope slide to improve the strength and the handling of the platform.

Custom nylon mesh fabrication

A nylon mesh with a pore size of 100 \(\upmu\)m (Lythe Official, Whitby YO21 3RT, UK) was modified by adding a frame of a biocompatible 3D printing resin (SolusArt v3.0, Gesswein, USA) following a customised fabrication process using a Digital Light Processing 3D printer (DLP, Microlay, Versus 385 nm, Spain). A sheet of the nylon mesh was cut with the size of the 3D printer build platform and taped it with special double-side adhesive tape (No.99786, 3M, USA) of 1 cm width and 0.3 mm thickness on the four edges of the building platform. The 3D resin was cured layer by layer following the CAD design of a ring of 6 mm outer diameter and 5.5 mm internal diameter, resulting in an embedded nylon mesh inside a rigid ring-shaped frame formed by the cured 3D resin. We show the mesh itself in Fig. 2A.

Experimental setup with the custom nylon mesh used to allow flow-driven perfusion studies in a microfluidic chip. (A) Schematic image of the nylon mesh used and T\(_1\)-FLASH sagittal images of the 4-well chip used containing the scaffolds at the bottom (water signal from the scaffold) before (top) and after (bottom) injecting water. We highlighted the well region with dashed green lines and the one with meshes in pink. (B) Protocol conducted to execute all flow-driven perfusion experiments with scaffolds using a 4-well (Fig. 1) microfluidic chip and a custom mesh to keep them in place.

Magnetic resonance imaging for diffusion and flow-driven perfusion studies

The MRI images were obtained using a dual-tuned \(^1\)H-\(^{13}\)C volume coil (42 mm inner diameter, Bruker®) inside a horizontal preclinical 3T MRI scanner (BioSpec 105 mm bore diameter, Bruker®). Magnetic field inhomogeneities were corrected with a shimming protocol applied to a water-filled Eppendorf prior to imaging. We used ParaVision 360 version 3.4 to acquire the images in the 3 T MRI scanner.The magnetic resonance proton images were acquired using a T\(_1\) FLASH sequence with the following acquisition parameters: echo time 9 ms, repetition time 425 ms, \(60^{\circ }\) flip angle, 4 averages, \(192\times 128\) image pixel size, \(10\times 40\) cm over a 192 \(\times\) 128 matrix yields \(0.52\times 3.125\) mm voxels with a slice thickness of 20 mm, 1 slice, 2 dummy scans of 849.787 ms, acquired with linear encoding, a bandwidth of 13,888.9 Hz, a working frequency of 127.64 MHz and a working chemical shift of 4.7 ppm. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (22 \(^\circ\)C) controlled by air conditioning.

For diffusion experiments, 0.5 mL Eppendorf tubes were filled with deuterium oxide (D\(_2\)O) and introduced the scaffold under study in them. Immediately after insertion of the scaffolds, the proton MRI imaging sequence started to acquire a frame every 3 minutes and 48 s for about 4.4 h for the hydrogel (Fig. 3A) and 1.9 hours for the cryogel (Fig. 3D). We then manually defined the scaffold and the Eppendorf tube regions of interest (ROIs). This experiments were performed with 1 replicate for each biomaterial.

For liquid penetration experiments, the scaffolds were placed in the dry microfluidic chip wells. To prevent the formation of air bubbles within the microfluidic channels, the channels were first pre-filled with D\(_2\)O, subsequently removing all residual D\(_2\)O from the well and drying it thoroughly using Kimwipes. This last step helped to prevent the contact between the preloaded D\(_2\)O with the water present in the scaffold. Then, the custom-made meshes (Fig. 2A) were placed on top of the scaffolds to ensure the perfusivity of the system while preventing lateral bypass. This process was performed within a couple of minutes. D\(_2\)O was injected through the microfluidic channels to mimic perfusion across the scaffolds (Fig. 2B). We used controlled flow rates of 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 mL/min. For manual injections, we estimated a varying flow rate of \(\approx\) 10–50 mL/min (3 replicates). The system was imaged before and after injection to identify the location of the water proton signal, as MRI cannot capture real-time dynamics during fast injections. We then manually defined the scaffold and well ROIs. Also, note that any flow rate value reported was the one used for the injection through the syringe pump, which, when distributed across the 4 parallel channels, causes the flow rate in the well to be one-quarter of the original one, as the split is symmetric.

Data processing and analysis

Bruker’s inbuilt acquisition software (ParaVision 360, version 3.4) was used to process all the proton MRI images acquired and obtain the subsequent DICOM files. From the DICOM images, we defined the ROIs required (i.e. scaffold and container region) using ImageJ (version 2.14.0) and generated binary masks from them. At this point, all the data was processed using custom-made Python scripts (version 3.10.9) to extract pixel intensity values and compute region averages or sums from individual ROIs. All the data and scripts generated for the processing are available in the GitHub repository ScaffoldsDifPerfPaper_2023.

Results

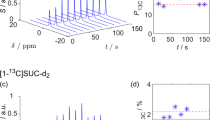

Diffusion studies of commonly used biocompatible scaffolds using MRI. Sagittal proton images at different times of an Eppendorf containing D\(_2\)O and a water-saturated 10% PEGDA hydrogel (A) or 1% CMC cryogel (D). The pixel threshold was individually adjusted in each image to improve visualization. For each image shown, a kernel density estimation of the pixel intensity inside the container for both the hydrogel (B) and the cryogel (E) is displayed, indicating a starting point of a distribution with a long right tail (high proton signal located in a small spatial region) evolving to a normal distribution due to the diffusion of water particles in the whole Eppendorf. Plots of the mean pixel intensity for the scaffold region (green) and the rest of the container (blue) for all images acquired every 3 minutes and 48 seconds during 4 h and 22 min for the PEGDA hydrogel (C) and 1 hour and 54 min for the CMC cryogel (F). In both plots, the vertical lines specify the time frames of the MRI images.

Assessment of passive diffusion properties of bio-compatible scaffolds using MRI

Firstly, we used MRI to test the passive diffusion (or liquid exchange within the scaffold under pure diffusion conditions) of water in both a 10% PEGDA hydrogel (Fig. 3A) and a 1% CMC cryogel (Fig. 3D). We observed the passive diffusion of water out of a scaffold by proton MRI imaging and using D\(_2\)O as a contrast agent. Since H\(_2\)O and D\(_2\)O contain labile hydrogen isotopes, we expected HDO formation via exchange reactions. This effect would also confirm contact between the two liquids and contribute to the observed signal decrease. Analysing the distribution of pixel intensities inside the container used, we observed that both the hydrogel (Fig. 3B) and the cryogel (Fig. 3E) showed water molecule exchange with the surrounding media following Fick’s laws of passive diffusion. First, the proton signal intensity arose only from the scaffold, making a subsection of the ROI to have high pixel intensities (i.e. water-soaked scaffold). Hence, signals close to the machine’s background noise dominated the image. The first kernel density estimates of Fig. 3B,E show this phenomenon for both scaffolds. The highest probability region is located around the background noise value, with the distribution having a long right tail, representing the few scaffold ROI pixels with high intensity. As time progressed, the passive diffusion observed in both cases uniformly distributed the protonated water molecules across the entire container. Consequently, the kernel density estimates evolved towards Gaussian distributions, this time centred at the mean pixel intensity instead of the background ones.

As shown in Fig. 3C, the PEGDA hydrogel exhibited a fast water molecule exchange at the beginning of the analysis, potentially from the water particles surrounding the scaffold on their immediate surface. However, the water trapped in the scaffold’s core took longer to diffuse out. The system appeared to reach equilibrium 2 h and 40 min into the experiment. This diffusion resulted in a time constant of [\(3.31 \pm 0.08] \cdot 10^{-2} \; \textrm{s}^{-1}\) (with a mean squared error of \(5.89 \cdot 10^{-4}\)) when fitting an exponential function (\(A \cdot e(-t\cdot B)\)) to the progression of water intensity within the container (Fig. 3C, blue line). However, the scaffold ROI retained the highest \(^1\)H signal intensity (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, the CMC cryogel showed a more uniform diffusion for its enclosed water, with the system stabilising after 1 h and 20 min, as shown in Fig. 3F. The cryogel presented a diffusion time constant of [\(1.67 \pm 0.06] \cdot 10^{-2} \; \textrm{s}^{-1}\) (with a mean squared error of \(1.43 \cdot 10^{-3}\)), making its diffusion approximately twice as fast as for the hydrogel. Furthermore, the pixel intensities in the \(^1\)H images (Fig. 3D) were more uniformly distributed by the end of the experiment, suggesting complete diffusion of all the water contained in the scaffold. The ADC measured, both for restricted and free water (i.e. inside and outside the cryogel scaffold), was \((2.1 \pm 0.1) \times 10^{-3} \; \textrm{mm}^2/\textrm{s}\), underscoring the high porosity and low tortuosity within the biomaterial.

MRI-based evaluation of liquid penetration in biocompatible scaffolds using microfluidic systems

In certain scientific scenarios, such as the study of drug delivery or metabolic imaging by hyperpolarisation-enhanced MRI, rapid liquid penetration into the scaffold (in the range of a few seconds) is a requirement to prevent deterioration of the injected reagent54,55,56. For this reason, to assess flow-driven perfusion, we placed the scaffolds in wells within custom-designed microfluidic chips. These devices are also used in the bioengineering field to create the so-called organ-on-a-chip devices57. Figure 2B shows the schematic procedure, where a scaffold is inserted into a chip well, and the mesh is added on top to allow fluid flow into scaffolds. In this section, we defined the ROI of the scaffold as the area of the well below the mesh.

Assessment of fast flow-driven perfusion processes for 10% PEGDA hydrogels

Our strategy to study the flow-driven perfusion properties of scaffolds brought attention to the challenges associated with extracting water from the core of PEGDA hydrogels during manual D\(_2\)O injections. The customised meshes fulfilled their purpose by effectively retaining the scaffolds at the bottom of the wells, compelling the injected solution to traverse through the scaffolds. However, even in this case, the water proton signal located in the scaffold region was consistently detected, indicating poor liquid passage of the contrast agent through the PEGDA hydrogel scaffolds. We can observe this phenomenon in Fig. 4A, where some water proton signal (pink) appears at the bottom of the chip’s wells after the D\(_2\)O injection. On average, [\(16.75 \; \pm \; 9\)]% of water remained inside the scaffold after injection. By representing the horizontal pixel sum of each well, as shown in Fig. 4B, we can more evidently observe the presence of water signal after the flow-driven perfusion test, represented by spikes of signal at the bottom of the well in all tests performed.

Assessment of flow-driven perfusion processes for 1% CMC cryogel scaffolds

We reliably and reproducibly detected complete perfusivity of the injected D\(_2\)O in the water-soaked 1% CMC cryogel scaffolds, again performing manual injections and varying controlled flow rates with a syringe pump. The manual injection took approximately 2-4 seconds. The injections performed at pre-defined flow rates went from 12 min in the slowest injection (0.1 mL/min) to 7 seconds for the fastest (10 mL/min). Compared to the experiments performed with manual injections in the PEGDA hydrogel, when using a 1% CMC cryogel, all the D\(_2\)O injected passed through the scaffold, removing all the water from the scaffold and placing it at the top of the well. We can observe this process in the proton images from Fig. 5A and confirm the absence of proton signal after injection by looking at the horizontal pixel sum of each well shown in Fig. 5B. Despite having four replicates per experiment (four independent wells in the chip), we repeated this experiment three times to ensure the flow-driven perfusion process efficiency and reproducibility of the cryogel tested. As we indicate in Fig. 5C, the results were consistent at each trial, forcing all the water proton signal out of the scaffold into the top of the well after the injection of D\(_2\)O. We attributed the small statistical difference between the first two replicates of the pre-injection scenario (assessed using a non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with p value of 0.029) to the different water content between scaffolds caused by the intrinsic nature of pore formation in these. All other comparisons resulted in p values higher than 0.1.

Furthermore, MRI allowed us to determine that the flow-driven perfusion process properties of the 1% CMC cryogel were consistent in a wide range of flow rates. We substituted the hardly reproducible manual injection with a controlled one, leveraging an automatic syringe pump to inject the deuterium oxide. We selected a range of flow rates to represent common ones used for continuous media recirculation in microfluidic devices58, going up to the maximum allowed by our pump. As previously done, we placed a single scaffold in each well of the microfluidic chip used and injected D\(_2\)O at different flow rates for each experiment. As represented in Fig. 5D, in all cases, the water proton signal was removed from the scaffold region and pushed to the top of the well. Also, the low variability in the box plots for the post-injection indicates that the water proton signal was displaced to the top of the well (T ROI) for all the wells in every experiment.

Flow-driven perfusion studies of cryogels using MRI. (A) Sagittal proton MRI image composite of the 4-well chip containing a 1% CMC cryogel in each well. (B) Horizontal pixel sum of each well ROI from panel (A). (C) Average pixel intensity of the four wells scaffold region at the bottom of the image (B ROI) over the rest of the well at the top (T ROI) for three replicates of an experiment with a single 1% CMC cryogel per well. (D) Pixel average of the four wells B ROI over T ROI for experiments with a single 1% CMC cryogel per well injecting the D\(_2\)O at different flow rates (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 mL/min).

Assessment of controlled flow-driven perfusion processes in CMC cryogel scaffolds with varying compositions and stacked configurations

With this new approach of assessing scaffold physical properties, we determined that denser cryogels present higher liquid resistance, hindering liquids from passing through the scaffold, particularly at high flow rates. To further validate the capabilities of MRI to study flow-driven perfusion processes, we tested cryogels with a different CMC% (w/w), modifying their stiffness, density and porosity. Velasco et al. extensively characterized the pore diameter and distribution in Ref.2, reporting that at 5% CMC concentration, approximately 70% of the pores were smaller than 50 µm; at 1% CMC, >70% were below 75 µm; and at 0.5% CMC, the majority were under 100 µm . We made and tested cryogels with 0.5%, 1%, 2% and 5% of CMC. The initial tests, done at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, indicated perfusion issues only with the 5% CMC cryogel, with a displacement of \(\approx 55 \%\) of water outside of the scaffold. We show these issues in Fig. 6A, where there was still water proton signal at the bottom of the well (B ROI) after injecting D\(_2\)O, where the scaffold’s percentage of CMC is increasing from left to right. The horizontal pixel sum (Fig. 6B) clearly evidenced this fact, showing signal in the bottom region after injection of the contrast agent. We indicate the results for three different flow rates in Fig. 6C, where the 5% CMC cryogel only fully ejected its contained water at the lowest flow rate (i.e. 0.1 mL/min). To aid comparison, we normalised the results by the total signal measured for each well, where 1 indicates the total signal measured. We also observed this reduced perfusion when we stacked two 1% CMC cryogels in the same well (Fig. 6D), highlighting the significant influence of scaffold arrangement and fluid resistance. We supported this assumption by also reducing the flow rate in this case to 0.1 mL/min, where again there was a significant increase in fluid passage efficacy as indicated in Fig. 6E. Hence, MRI and D\(_2\)O as contrast agent seem adequate to determine the liquid passage efficiency of scaffolds of different stiffness, densities and porosities, uncovering some fluidic issues potentially caused by high resistances.

Flow-driven perfusion studies of cryogels with different CMC% composition using MRI. (A) Sagittal proton MRI image composite of the 4-well chip containing a 0.5%, 1%, 2% or 5% CMC cryogel in each well (from left to right). (B) Horizontal pixel sum of each well ROI from panel (A) . (C) Well region without scaffold (T ROI) pixel intensity normalised by the total one (T ROI + B ROI) for three experiments containing a 0.5%, 1%, 2% or 5% CMC cryogel in each well injecting D\(_2\)O at different flow rates (0.1, 1 and 5 mL/min). (D) Normalised T ROI for an experiment containing one or two 1% CMC cryogels in each well injecting D\(_2\)O at 5 mL/min. (E) Normalised T ROI pixel intensity for an experiment containing two 1% or one 5% CMC cryogels in each well injecting D\(_2\)O at 0.1 mL/min.

Discussion

A central question in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications is how rapidly a solute, such as a drug or a hyperpolarised metabolite, can reach cells embedded deep within a 3D scaffold. However, standard MRI or DWI techniques often fall short in resolving such fluid transport dynamics within porous materials due to their limited spatial and temporal resolution or reliance on indirect measurements.

In this study, we used MRI to investigate the diffusion and flow-driven perfusion properties of biocompatible porous scaffolds commonly employed in 3D cell culture models. The use of D\(_2\)O and the difference in spin number between deuterium and hydrogen played a key role in our approach, enabling us to track water exchange and diffusion dynamics with high sensitivity.

By immersing water-filled scaffolds within a sealed D\(_2\)O-containing container, we observed a progressive signal loss originating from water diffusion out of the scaffold and into the surrounding medium. The observed signal attenuation, together with the expected formation of HDO via proton–deuteron exchange, provided a direct and quantitative readout of liquid infiltration and molecular exchange within the scaffold. As H\(_2\)O and D\(_2\)O have labile hydrogen isotopes, we anticipated the formation of HDO through an exchange reaction. However, since we are observing bulk species by proton density, and the proton Larmor frequency of H\(_2\)O and HDO are very similar, we did not expect a representative effect in the measurements. The cryogel scaffolds, composed of approximately 98% water59, exhibited negligible diffusional resistance, as evidenced by the identical ADCs measured inside and outside the scaffold. These results confirmed the exceptionally high porosity and low tortuosity of the cryogels, critical properties for facilitating rapid mass transfer. Importantly, the fact that the measured ADC within the scaffold matches that of bulk water establishes a physical upper limit for diffusivity in such porous systems, since, in contexts such as ours (bio-compatible scaffolds), the maximum diffusivity rate achieved will be limited in its maximum by the free water60,61.

The comparison of CMC and PEGDA-based scaffolds revealed clear differences in diffusion rate constants. The 10% PEGDA scaffold, a commonly used concentration in biomaterials, exhibited two times lower diffusion efficiency compared to CMC cryogels. Beyond passive diffusion, our study also assessed liquid penetration (i.e., flow-driven perfusion) properties of the scaffolds using microfluidic systems, where we actively introduced liquid via a controlled injection. MRI allowed us to determine that the flow-driven perfusion properties of 1% CMC cryogels remained consistent across a wide range of flow rates. By replacing manual injection with an automatic syringe pump, we ensured reproducibility and controlled fluid delivery, selecting flow rates representative of those commonly used in continuous media recirculation within microfluidic devices58. The results, depicted in Fig. 5D, show that in all cases, the water proton signal was removed from the scaffold region and displaced to the top of the well. The low variability in post-injection signal distributions further supports the robustness of this process.

The comparison between CMC cryogels and PEGDA hydrogels in a flow-driven perfusion setting revealed significant differences in fluid transport efficiency. While PEGDA hydrogels permitted liquid passage, their efficiency was markedly lower than that of CMC cryogels. In a similar study, Admane et al. used gadolinium-based contrast agents to assess the perfusion properties of a gelatin-based hydrogel embedded with fibroblasts. Their results demonstrated flow-driven perfusion throughout the construct, with gadolinium reaching the entire scaffold within approximately 90 minutes23. This effect has direct implications for applications requiring rapid and uniform fluid exchange, such as hyperpolarisation-enhanced MRI, where the contrast agent has a limited lifetime of 1–2 minutes and must be delivered swiftly53. Similarly, in therapeutic applications, ensuring complete washout of a previously administered drug is critical54. Our findings indicate that 10% PEGDA hydrogels would be unsuitable for these high-exchange requirements, whereas cryogels offer a superior alternative for efficient fluid transport.

Further analysis of stacked scaffolds provided additional insights into the role of scaffold arrangement and resistance to fluid flow. When we stacked two 1% CMC cryogels in the same well (Fig. 6D), we observed a reduction in perfusion efficiency, suggesting that scaffold disposition significantly affects liquid passage. Additionally, for denser and less porous scaffolds, higher pore resistance at elevated flow rates resulted in incomplete fluid displacement. The horizontal pixel sum analysis highlighted this phenomenon (Fig. 6B), which revealed signal retention in the bottom region of the scaffold even after contrast agent injection. The results for three different flow rates (Fig. 6C) further confirmed that the 5% CMC cryogel only fully ejected its contained water at the lowest tested flow rate.

In this work, we used a 3T preclinical MRI scanner and a volume RF coil. We would achieve better sensitivity by using a quadrature \(^1\)H coil and/or at a higher B\({_0}\) magnetic field. At higher fields, techniques such as diffusion MRI and diffusion tensor imaging could enhance the accuracy of diffusion measurements62, while faster T\(_1\) imaging could improve temporal resolution, albeit at the cost of reduced proton signal quantification. Future research should explore the development of more advanced phantoms and scaffold holders to enhance experimental reproducibility, including better control over positioning and temperature stability.

Our results demonstrate an efficient and cost-effective method to study diffusion and flow-driven perfusion processes in porous biomaterials. This method is accessible to non-expert users and provides a straightforward means of characterising fundamental scaffold properties, such as diffusivity, which are critical for applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery systems. Other MRI techniques, such as tortuosity analysis and relaxometry63, have been employed to study porous materials. However, these methods require more complex data acquisition and processing and provide only indirect measurements. Additionally, contrast agents like gadolinium have been used to investigate diffusion and perfusion in porous materials64. Nevertheless, we opted for D\(_2\)O because it provides a direct and quantitative method for assessing liquid exchange without the need for contrast agents that could alter the chemical environment or interact with the scaffold material. Unlike gadolinium-based contrast agents, which primarily enhance relaxivity, D\(_2\)O directly replaces H\(_2\)O molecules, leading to measurable signal attenuation due to the loss of hydrogen protons. This property allows for a straightforward and reproducible analysis of liquid penetration and exchange dynamics. Moreover, the use of D\(_2\)O eliminates the need for additional calibration steps typically required for contrast-based imaging, simplifying the experimental workflow while maintaining high sensitivity to diffusion and perfusion processes.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates the utility of MRI to evaluate both passive diffusion and active flow-driven perfusion processes in biocompatible scaffolds. Our findings highlight the advantages of cryogels for applications requiring rapid and uniform liquid exchange, and underscore the potential of MRI-based techniques to enhance scaffold design and performance in biomedical research. The method’s versatility and reproducibility across different experimental conditions positions it as a robust tool for future studies in tissue engineering and fluid transport in biomaterials. Future work should explore a broader range of scaffold compositions (including synthetic, natural, and hybrid hydrogels)while systematically varying concentration and flow parameters. This approach also holds promise for drug release studies and real-time monitoring applications.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. All the data and scripts generated for the processing are available in the GitHub repository ScaffoldsDifPerfPaper_2023.

References

Bilici, C., Altunbek, M., Afghah, F., Tatar, A. G. & Koç, B. Embedded 3d printing of cryogel-based scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. (2023).

Velasco-Mallorquí, F., Rodríguez-Comas, J. & Ramón-Azcón, J. Cellulose-based scaffolds enhance pseudoislets formation and functionality. Biofabrication 13, 035044 (2021).

Newland, B. & Long, K. R. Cryogel scaffolds: soft and easy to use tools for neural tissue culture. Neural Regen. Res. 17, 1981 (2022).

Aguado, B. A., Grim, J. C., Rosales, A. M., Watson-Capps, J. J. & Anseth, K. S. Engineering precision biomaterials for personalized medicine. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaam8645 (2018).

Annabi, N. et al. Controlling the porosity and microarchitecture of hydrogels for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 16, 371–383 (2010).

Spicer, C. D. Hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering: The importance of polymer choice. Polym. Chem. 11, 184–219 (2020).

Tibbitt, M. W. & Anseth, K. S. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3d cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 103, 655–663 (2009).

Mangas-Florencio, L. et al. A diy bioreactor for in situ metabolic tracking in 3d cell models via hyperpolarized 13c nmr spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. (2025).

Henderson, T. M., Ladewig, K., Haylock, D. N., McLean, K. M. & O’Connor, A. J. Cryogels for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 1, 2682–2695 (2013).

Yue, K. et al. Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of gelatin methacryloyl (gelma) hydrogels. Biomaterials 73, 254–271 (2015).

Foudazi, R., Zowada, R., Manas-Zloczower, I. & Feke, D. L. Porous hydrogels: Present challenges and future opportunities. Langmuir 39, 2092–2111 (2023).

Griveau, L. et al. Design and characterization of an in vivo injectable hydrogel with effervescently generated porosity for regenerative medicine applications. Acta Biomater. 140, 324–337 (2022).

Yanez, F., Gomez-Amoza, J. L., Magarinos, B., Concheiro, A. & Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Hydrogels porosity and bacteria penetration: Where is the pore size threshold?. J. Membr. Sci. 365, 248–255 (2010).

Lee, M. K., Rich, M. H., Baek, K., Lee, J. & Kong, H. Bioinspired tuning of hydrogel permeability-rigidity dependency for 3d cell culture. Sci. Rep. 5, 8948 (2015).

Cao, R., Avgoustiniatos, E., Papas, K., de Vos, P. & Lakey, J. R. Mathematical predictions of oxygen availability in micro-and macro-encapsulated human and porcine pancreatic islets. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 108, 343–352 (2020).

Farris, A. L., Rindone, A. N. & Grayson, W. L. Oxygen delivering biomaterials for tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 4, 3422–3432 (2016).

Gholipourmalekabadi, M., Zhao, S., Harrison, B. S., Mozafari, M. & Seifalian, A. M. Oxygen-generating biomaterials: a new, viable paradigm for tissue engineering?. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 1010–1021 (2016).

Herrero-Gómez, A., Azagra, M. & Marco-Rius, I. A cryopreservation method for bioengineered 3d cell culture models. Biomed. Mater. 17, 045023 (2022).

Gun’ko, V. M., Savina, I. N. & Mikhalovsky, S. V. Cryogels: Morphological, structural and adsorption characterisation. Adv. Coll. Interface. Sci. 187, 1–46 (2013).

Loo, S.-L. et al. 3d photothermal cryogels for solar-driven desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 30542–30555 (2021).

Koch, M., Vrij, E., Engel, E., Planell, J. & Lacroix, D. Perfusion cell seeding on large porous pla/calcium phosphate composite scaffolds in a perfusion bioreactor system under varying perfusion parameters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 95, 1011–1018 (2010).

Lauritsen, S. et al. Bioreactor for quantification of cell metabolism by mr-hyperpolarization. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 1, 047003 (2015).

Admane, P. et al. Multimodal imaging compatible micro-physiological system. Bioprinting 29, e00249 (2023).

Adeoye, A. J. & de Alba, E. A simple method to determine diffusion coefficients in soft hydrogels for drug delivery and biomedical applications. ACS Omega 10, 10852–10865 (2025).

Evans, S. M. et al. A microfluidic method to measure small molecule diffusion in hydrogels. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 35, 322–334 (2014).

Jaeger, F., Bowe, S., Van As, H. & Schaumann, G. Evaluation of 1h nmr relaxometry for the assessment of pore-size distribution in soil samples. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 60, 1052–1064 (2009).

Ouellet, S., Bussière, B., Aubertin, M. & Benzaazoua, M. Microstructural evolution of cemented paste backfill: Mercury intrusion porosimetry test results. Cem. Concr. Res. 37, 1654–1665 (2007).

Shah, S., Gray, F., Crawshaw, J. & Boek, E. Micro-computed tomography pore-scale study of flow in porous media: Effect of voxel resolution. Adv. Water Resour. 95, 276–287 (2016).

Ritman, E. L. Micro-computed tomography\(-\)current status and developments. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 6, 185–208 (2004).

Lui, Y., Tang, E., Allmendinger, A. & Spektor, V. Evaluation of ct perfusion in the setting of cerebral ischemia: patterns and pitfalls. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 31, 1552–1563 (2010).

Landis, E. N. & Keane, D. T. X-ray microtomography. Mater. Char. 61, 1305–1316 (2010).

Kraus, B. B., Ros, P. R., Abbitt, P. L., Kerns, S. R. & Sabatelli, F. W. Comparison of ultrasound, ct, and mr imaging in the evaluation of candidates for tips. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 5, 571–578 (1995).

Jacobson, J. A. Musculoskeletal ultrasound and mri: which do i choose? In Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology, vol. 9, 135–149 (Copyright 2005 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New., 2005).

Wong, H. K. et al. Novel method to improve vascularization of tissue engineered constructs with biodegradable fibers. Biofabrication 8, 015004 (2016).

Than, A. et al. Self-implantable double-layered micro-drug-reservoirs for efficient and controlled ocular drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 9, 4433 (2018).

Tripathi, S., Champagne, D. & Tufenkji, N. Transport behavior of selected nanoparticles with different surface coatings in granular porous media coated with pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 6942–6949 (2012).

Osborne, M., Balasubramanian, S., Furey, W. & Klenerman, D. Optically biased diffusion of single molecules studied by confocal fluorescence microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3160–3167 (1998).

Demchenko, A. P. Photobleaching of organic fluorophores: quantitative characterization, mechanisms, protection. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 8, 022001 (2020).

Klonis, N. et al. Fluorescence photobleaching analysis for the study of cellular dynamics. Eur. Biophys. J. 31, 36–51 (2002).

Bae, W. C. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging assessed cortical porosity is highly correlated with \(\mu\)ct porosity. Bone 66, 56–61 (2014).

Cooper, D., Kawalilak, C., Harrison, K., Johnston, B. & Johnston, J. Cortical bone porosity: what is it, why is it important, and how can we detect it?. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 14, 187–198 (2016).

Bae, W. C. et al. Quantitative ultrashort echo time (ute) mri of human cortical bone: correlation with porosity and biomechanical properties. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 848–857 (2012).

Camaiti, M., Bortolotti, V. & Fantazzini, P. Stone porosity, wettability changes and other features detected by mri and nmr relaxometry: a more than 15-year study. Magn. Reson. Chem. 53, 34–47 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Measurement and visualization of tight rock exposed to co2 using nmr relaxometry and mri. Sci. Rep. 7, 44354 (2017).

Hak, S. et al. A high relaxivity gd (iii) dota-dspe-based liposomal contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 72, 397–404 (2009).

Shellock, F. G. & Kanal, E. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 10, 477–484 (1999).

Denisov, V. P. & Halle, B. Hydrogen exchange and protein hydration: the deuteron spin relaxation dispersions of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor and ubiquitin. J. Mol. Biol. 245, 698–709 (1995).

Callaghan, P. T., Le Gros, M. & Pinder, D. N. The measurement of diffusion using deuterium pulsed field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 6372–6381 (1983).

Pohlmeier, A., van Dusschoten, D., Weihermüller, L., Schurr, U. & Vereecken, H. Imaging water fluxes in porous media by magnetic resonance imaging using d2o as a tracer. Magn. Reson. Imaging 27, 285–292 (2009).

Wang, F.-N., Peng, S.-L., Lu, C.-T., Peng, H.-H. & Yeh, T.-C. Water signal attenuation by d2o infusion as a novel contrast mechanism for 1h perfusion mri. NMR Biomed. 26, 692–698 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. Deuterium oxide as a contrast medium for real-time mri-guided endovascular neurointervention. Theranostics 11, 6240 (2021).

Qin, D., Xia, Y. & Whitesides, G. M. Soft lithography for micro-and nanoscale patterning. Nat. Protoc. 5, 491 (2010).

Yeste, J. et al. Parallel detection of chemical reactions in a microfluidic platform using hyperpolarized nuclear magnetic resonance. Lab Chip 23, 4950–4958 (2023).

Garg, T., Singh, O., Arora, S. & Murthy, R. Scaffold: a novel carrier for cell and drug delivery. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 29 (2012).

Marco-Rius, I. & Comment, A. In vivo hyperpolarized 13c mrs and mri applications. 405–419 (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Marco-Rius, I. et al. Monitoring acute metabolic changes in the liver and kidneys induced by fructose and glucose using hyperpolarized [2-13c] dihydroxyacetone. Magn. Reson. Med. 77, 65–73 (2017).

Boulais, L. et al. Cryogel-integrated biochip for liver tissue engineering. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 5617–5626 (2021).

Bergemann, C. et al. Cellular nutrition in complex three-dimensional scaffolds: a comparison between experiments and computer simulations. Int. J. Biomater. 2015 (2015).

Velasco-Mallorquí, F., Fernández-Costa, J. M., Neves, L. & Ramón-Azcón, J. New volumetric cnt-doped gelatin-cellulose scaffolds for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Nanoscale Adv. 2, 2885–2896 (2020).

Pieciak, T. et al. Spherical means-based free-water volume fraction from diffusion mri increases non-linearly with age in the white matter of the healthy human brain. Neuroimage 279, 120324 (2023).

Duering, M. et al. Free water determines diffusion alterations and clinical status in cerebral small vessel disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14, 764–774 (2018).

Marco-Rius, I. et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of hyperpolarized [13c] urea in mouse liver. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 47, 141–151 (2018).

Maillet, B., Sidi-Boulenouar, R. & Coussot, P. Dynamic nmr relaxometry as a simple tool for measuring liquid transfers and characterizing surface and structure evolution in porous media. Langmuir 38, 15009–15025 (2022).

Thelwall, P. E., Neves, A. A. & Brindle, K. M. Measurement of bioreactor perfusion using dynamic contrast agent-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 75, 682–690 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank the MicroFabSpace and Microscopy Characterisation Facility, Unit 7 of ICTS “NANBIOSIS” from CIBER-BBN at IBEC.

Funding

This work has received funding from: The European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (GA-863037); a European Union ERC Starting Grant (GA-101165045, LIFETIME); the Spanish grants with reference PID2023-151470OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF/EU” (METACHIP), RYC2020-029099-I funded by MCIN/AEI10.13039/501100011033 and by “ESF Investing in your future”, PLEC2022-009256 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (FLASHonCHIP), a grant within the framework Biotechnology Plan Applied to Health funded by MCIN/AEI10.13039/501100011033 and co-financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation with funds from the European Union NextGenerationEU from the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan (PRTR-C17.I1); from the Autonomous Community of Catalonia within the framework of the Biotechnology Plan Applied to Health; the BIST (Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology)-“la Caixa” Banking Foundation Chemical Biology programme; and the ”Juan de la Cierva” grant IJC2019-040289-I by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A., D.G.C., A.P. and I.M.R. drafted and wrote the manuscript. M.A., A.P. and D.G.C. performed the experiments. M.A. did the data collection and CMC cryogel fabrication. D.G.C. performed the data processing and analysis. A.P. and G.M. designed the microfluidic chip and the mesh. G.M. fabricated the microfluidic chips used. N.T. and E.M. designed and fabricated the PEGDA hydrogels. I.M.R. provided guidance in project and manuscript design, raised funding and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azagra, M., Gomez-Cabeza, D., Portela, A. et al. Leveraging magnetic resonance imaging to assess biocompatible scaffolds diffusion and flow-driven perfusion for lab-on-a-chip systems. Sci Rep 15, 45392 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28465-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28465-w