Abstract

In response to existing compressed sensing ghost imaging (CSGI) schemes, an innovative Bayesian compressed sensing ghost imaging with better anti-noise performance is proposed, by using the sparse representation of K-Singular Value Decomposition (KSVD) and a 3Level (3L)-hierarchical variational message passing (VMP) algorithm. Simulation and experimental results confirm that, this innovative method overcomes the limitations of presetting specific parameters (sparsity, noise level, etc.), and also demonstrates superior performance in terms of reconstruction accuracy and imaging quality, especially for highly complex objects, where it effectively achieves accurate imaging under varying levels of noise at a low sampling rate (below 12.2%). In addition, compared to existing Bayesian compressive sensing ghost imaging (BCSGI), our algorithm moderately reduces time consumption while ensuring high precision. Our results may provide potential applications of CSGI in the field of biomedical imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ghost imaging (GI) has garnered increasing attention due to its novel non-local imaging technique, which reconstructs the image of an object by correlation calculation between two correlated beams. GI was first experimentally validated in 1995 using entangled photon pairs1. Later, it is demonstrated theoretically and experimentally that thermal source and pseudo-thermal source can also be employed to achieve GI2,3. Shapiro further enhanced the technique by introducing computational ghost imaging (CGI)4. Notably, a variety of reconstruction algorithms have been proposed to enhance the imaging quality of GI, such as differential ghost imaging (DGI)5, normalized ghost imaging (NGI)6, pseudo-inverse ghost imaging (PGI)7. However, these algorithms typically require a larger number of samples. And deep learning-based ghost imaging (GIDL)8, which also requires a substantial training data to learn effective feature representations. It is noted that compressed sensing ghost imaging (CSGI) leverages the sparsity of signals to achieve precise reconstruction with a number of samples far less than what is required by the traditional sampling theorem9, which significantly enhanced the imaging efficiency.

Over the years, a growing number of compressed sensing (CS) algorithms have been applied in the field of GI. Pioneering studies have integrated greedy algorithms such as matching pursuit (MP)10 and orthogonal matching pursuit (OMP)11 into the CSGI system, treating the image reconstruction challenge as an optimization task. Nevertheless, greedy algorithms generally require the noise level parameter and sparsity as known conditions, which can be challenging to satisfy in practice, and the parameter settings, significantly affect the reconstruction results the OMPCSGI mentioned in this paper sets the sparsity parameter as \(T_0 =T/4\), T=measurement count). In contrast, the Bayesian learning model offers a notable advantage in its ability to frame the reconstruction problem of complex targets (such as biological tissues) under noisy conditions as an estimation problem of relevant signal parameters through Bayesian inference12. More recently, some studies have introduced Bayesian learning model into the GI system13,14,15, which use the parametrically obtained Gaussian distribution as the prior distribution of the solution (2Level (2L)-hierarchical prior model). It is worth mentioning that the 3Level (3L)-hierarchical prior model16, which adds a layer of latent variables based on the 2L-hierarchical model, enabling the Bayesian hierarchical model to handle more complex dependency structures. Moreover, the majority of studies utilize the discrete cosine transform (DCT) or the fast Fourier transform (FFT) for the sparse representation of signals (the traditional CSGI algorithm mentioned in this paper employs a sparse representation method using FFT). Despite the simplicity of their expressions, both fail to consider the distinctive attributes of individual signals. Consequently, they may not be the most optimal choices for signals that require a more adaptive and flexible approach to achieve the sparse representation. The algorithm of K-Singular Value Decomposition (KSVD)17 demonstrates robust adaptability to diverse complex image datasets, presenting a compelling alternative. This work extends the Bayesian K-SVD framework16 to CGI by two key innovations: (1) Dimensional equivalence-driven measurement model: The equivalence \(KP = L\) enables direct application of measurement matrix \(\varvec{\Phi }\) to sparse codes \(\varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}}\), simplifying reconstruction while maintaining accuracy. (2) 3L hierarchical prior: The Gaussian-Gamma-Gamma hierarchy explicitly models speckle noise statistics, enabling automatic sparsity adaptation without manual parameter tuning.

In this paper, we introduce a novel anti-noise Bayesian model in the CSGI system, which integrates the hierarchical 3L Bayesian model with the variational message passing algorithm (VMP)18,19 evolved by the generalized mean field (GMF)20, to estimate sparse representations of the image obtained through KSVD. To validate the applicability and effectiveness of the model we introduced, simple binary pattern, complex biological tissue, and real human blood cell sample are used as the target objects respectively. In addition, we consider the impact of noise at different levels to validate whether our algorithm outperforms others in terms of noise resistance. The peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), the correlation coefficient (\(r_{TG}\))21, and the structure similarity index measure (SSIM), as metrics, to assess the quality and accuracy of the reconstructed images. The results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm ensures high signal sparsity without the need for presetting sparsity, outperforming traditional GI (TGI)4 and OMP algorithm-based CSGI (OMPCSGI)22 in terms of the adaptability to data changes and the preservation of detailed information in real complex biological samples under noisy conditions, even if the sampling rate lower than 12.2%. In addition, our algorithm strikes a balance between time consumption and imaging accuracy when compared to existing Bayesian compressive sensing ghost imaging (BCSGI)14. Therefore, our approach may have great application potential in the identification of complex biological tissues in biomedicine.

Methods

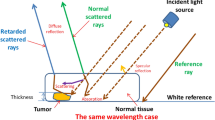

Principle of CSGI System

Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental schematic of CSGI. A digital projector emits random speckle patterns \(\{I_i\}_{i=1}^M\), where each pattern \(I_i \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\) is vectorized as \(\varvec{\phi }_i = \text {vec}(I_i) \in \mathbb {R}^{L}\) (\(L = n^2\)), with \(\text {vec}(\cdot )\) denoting the vectorization operator that stacks matrix columns into a column vector. Subsequently, the light transmits through the target object \(\textbf{W} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\) and is detected by a single-pixel detector. The measurement vector is \(\textbf{B} = [B_1, \dots , B_M]^\top \in \mathbb {R}^M\). The forward model with noise is expressed as9,23:

where \(\varvec{\Phi } = [\varvec{\phi }_1, \varvec{\phi }_2, \cdots , \varvec{\phi }_M]^\top \in \mathbb {R}^{M \times L}\) and \(\textbf{N} \sim \mathcal {N}(0, \lambda ^{-1}\textbf{I}_M)\), with \(\lambda > 0\) being the noise precision (inverse variance). \(\textbf{w} = \text {vec}(\textbf{W}) \in \mathbb {R}^L\) is the vectorized target object, \(L = n^2\).

For Bayesian reconstruction of sparse signals in CSGI, the target object \(\textbf{W}\) should possess a sparse representation. However, since natural images typically lack inherent sparsity, we employ the KSVD algorithm to construct an adaptive sparse representation. The image \(\textbf{W}\) is divided into P non-overlapping patches of size \(p \times p\) (where \(d = p^2\)). In this paper, we set \(p=8\) (\(d=64\)) for computational efficiency, but the method generalizes to arbitrary patch sizes. The image \(\textbf{W}\) is reconstructed by assembling the sparse-represented patches:

where \(\textbf{D}\) is the learned dictionary (\(\mathbb {R}^{d \times K}\)), \(\varvec{\alpha }\) is the sparse coefficient matrix (\(\mathbb {R}^{K \times P}\)), \(\textbf{R}\) reassembles the reconstructed patches \(\textbf{D}\varvec{\alpha }\) into the full image, the constraint \(\Vert \varvec{\alpha }_i\Vert _0 \le T_0\) applies independently to each patch representation \(\varvec{\alpha }_i\) (specifically the i-th column of \(\varvec{\alpha }\)), \(\Vert \mathbf {\cdot }\Vert _0\) denotes the \(\ell _0\)-norm defined as the number of the non-zero elements in a vector, and \(T_0\) represents the sparsity level indicating the maximum allowable non-zero coefficients per patch.

CSGI based on sparse representation and Bayesian estimates

Traditional GI reconstruction techniques like OMP and MP require manual tuning of the sparsity level (\(T_0\)) and exhibit significant noise sensitivity. The proposed CSGI framework, which integrates KSVD dictionary learning and Bayesian 3L-Prior estimation, overcomes these limitations by providing the following benefits: (1) Robust reconstruction under ultra-low sampling rates (<12.5%), (2) Automatic sparsity adaptation without manual parameter tuning, and (3) Explicit noise modeling for speckle-correlated measurements.

Sparse representation via KSVD

Unlike orthonormal bases (e.g., DCT), KSVD learns the dictionary that maximizes sparsity through adaptive representation of image patches, solving a bilevel optimization problem17. The image \(\textbf{W} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\) is partitioned into P non-overlapping patches of size \(p \times p\) (where \(d = p^2\)), with stride equal to patch size (\(\text {stride} = p\)). Each patch is vectorized into \(\textbf{y}_i \in \mathbb {R}^{d}\), forming the training matrix \(\textbf{Y} = [\textbf{y}_1, \dots , \textbf{y}_P] \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times P}\) (\(\textbf{W} = \textbf{R}(\textbf{Y})\)). We seek a dictionary \(\textbf{D} \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times K}\) and sparse codes \(\varvec{\alpha } = [\varvec{\alpha }_1, \dots , \varvec{\alpha }_P] \in \mathbb {R}^{K \times P}\) that solve:

where \(\varvec{\alpha }_i \in \mathbb {R}^K\) denotes the sparse representation vector for the i-th patch. The optimization alternates between sparse coding (via OMP) and dictionary update. Detailed steps are provided in Appendix A, and a more detailed explanation and specific mathematical formulations can be found in the relevant literature 16,24.

The use of non-overlapping tiling (stride p) in the KSVD dictionary learning stage is crucial for adapting to GI, which also effectively enhances computational efficiency. The KSVD algorithm operates on local patches but outputs a globally shared dictionary \(\textbf{D} \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times K}\) and a maximally sparse representation \(\varvec{\alpha } = [\varvec{\alpha }_1, \dots , \varvec{\alpha }_P] \in \mathbb {R}^{K \times P}\) stored patchwise. For Bayesian estimation, we vectorize it to obtain \(\varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}} = \text {vec}(\varvec{\alpha })= [\alpha _{11}, \dots , \alpha _{K1}, \alpha _{12}, \dots , \alpha _{KP}]^\top \in \mathbb {R}^{K P}\).

Sparse estimation using Bayesian 3L-hierarchical prior modeling

In the CGI phase illustrated in Fig. 1, the reconstruction problem is transformed into estimating the sparse coefficient vector \(\varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}} \in \mathbb {R}^{K P}\). For Bayesian reconstruction, we leverage the dimensional equivalence \(K P = L\) when \(K = d\) and \(P = (n/p)^2\). In our experimental setup (64\(\times\)64 images, p=8, K=64), \(K P = 64 \times 64 = 4096 = n^2 = L\). This simple equivalence, \(L = K P\), serves as a mathematical bridge from local sparse representations to the global GI model.

Specifically, this dimensional equivalence enables the linear reconstruction mapping \(\text {vec}(\textbf{W}) = \textbf{G} \varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}}\), where \(\textbf{G} = \textbf{R} (\textbf{I}_P \otimes \textbf{D}) \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times L}\) combines dictionary application and patch reassembly. Whereas the physical measurement model is \(\textbf{B} = \varvec{\Phi } \textbf{G} \varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}} + \textbf{N}\), we employ the computationally efficient model25:

This approximation is justified by three key factors: (1) The dimensional equivalence establishes a one-to-one correspondence between \(\varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}}\) and \(\text {vec}(\textbf{W})\), (2) KSVD reconstruction maintains high consistency with \(\textbf{G}\varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}} \approx \text {vec}(\textbf{W})\), and (3) The hierarchical priors compensate residuals through adaptive error tolerance.

Equation (4) establishes a linear relationship between \(\textbf{B}\) and \(\varvec{\alpha }_{vec}\) via \(\varvec{\Phi }\). This simplification retains sparsity while avoiding the explicit computation of \(\textbf{G}\), and adaptively compensates for the residual through the 3L hierarchical prior model described below.

3L hierarchical prior model: For notational simplicity, we denote \(\varvec{\alpha } \equiv \varvec{\alpha }_{\text {vec}}\) in Bayesian estimation. The likelihood \(f_{B_m}\) models bucket measurement \(B_m\) as Gaussian distributed with mean \(\left[ \varvec{\Phi }\varvec{\alpha }\right] _m\) and variance \(\lambda ^{-1}\), while the three-layer hierarchy decomposes the sparse coefficient prior \(p(\alpha _l)\) into a Gaussian conditional prior \(p(\alpha _l|\gamma _l)\) with precision \(\gamma _l\), a Gamma hyperprior \(p(\gamma _l|\eta _l)\), and a Gamma hyper-hyperprior \(p(\eta _l)\) with non-informative parameters \(a_l = 1\), \(b_l = 10^{-6}\). This ”Gaussian-Gamma-Gamma” hierarchy enables automatic sparsity adaptation while capturing speckle coherence properties. The joint probability distribution of this 3level hierarchy can be factorized as15,26:

This factorization maps to the factor graph in Fig. 2, which provides a visual representation of the hierarchical dependencies and message passing flow:

-

Variable nodes (circles) represent the random variables \(\varvec{\theta } = \{\varvec{\alpha }, \varvec{\gamma }, \varvec{\eta }, \lambda \}\)

-

Factor nodes (squares) encode probability distributions. \(\mathcal {N}(x|\mu ,F)\) represents a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu\) and covariance F. \(\mathcal {G}a(x|a,b)\) represents the Gamma distribution, with the equation given by \(\mathcal {G}a(x|a,b) = \frac{b^a}{\Gamma (a)} x^{a-1} \exp (-b x)\).

$$\begin{aligned}&f_{B_m}=p(B_m|\varvec{\alpha },\lambda ) = \mathcal {N}\left( B_m \mid \left[ \varvec{\Phi }\varvec{\alpha }\right] _m, \lambda ^{-1} \right) :\text {Global measurement model for bucket value}\, B_m \\&f_{\alpha _l}=p(\alpha _l|\gamma _l) = \mathcal {N}(\alpha _l|0, \gamma _l^{-1}):\text {Sparsity prior for sparse coefficient}\, \alpha _l \\&f_{\gamma _l}=p(\gamma _l|\eta _l) = \mathcal {G}a(\gamma _l|\epsilon , \eta _l) :\text {Hyperprior for variance parameter}\, \gamma _l \\&f_{\eta _l}=p(\eta _l) = \mathcal {G}a(\eta _l|a_l,b_l) :\text {Hyperprior-hyperprior for rate parameter}\, \eta _l\\&f_\lambda =p(\lambda ):\text {Prior for noise precision} \end{aligned}$$

Variational Message Passing: The closed-form updates for \(\theta = \{\varvec{\alpha }, \varvec{\gamma }, \varvec{\eta }, \lambda \}\) derive from applying VMP rules to the factor graph (Fig. 2). The adjacency structure restricts message passing to directly connected nodes, ensuring computational efficiency. The update rules derive from the mean-field approximation27:

where \(b(\theta _i)\) is belief (approximate posterior) of variable \(\theta _i\), \(m_{f_n \rightarrow \theta _i}\) is message from factor node \(f_n\) to variable node \(\theta _i\), \(\mathcal {N}_{\theta _i}\) is neighboring factor nodes of \(\theta _i\), and \(b(\varvec{\theta } \setminus \theta _i)\) denotes expectation over all variables except \(\theta _i\). Closed-form updates are obtained by exploiting conjugate prior properties:

-

1.

Sparse coefficients \(\varvec{\alpha }\): Combining messages \(m_{f_{B_m} \rightarrow \alpha }\) (from likelihood factors) and \(m_{f_{\alpha _l} \rightarrow \alpha _l}\) (from prior factors) via Eq. (6) yields28. That is, \(b(\varvec{\alpha }) \propto \left[ \prod _{m=1}^M m_{f_{B_m} \rightarrow \varvec{\alpha }} \right] \times \left[ \prod _{l=1}^L m_{f_{\alpha _l} \rightarrow \alpha _l} \right] = \exp \left( \langle \ln p(\textbf{B}|\varvec{\alpha },\lambda ) \rangle + \langle \ln p(\varvec{\alpha }|\varvec{\gamma }) \rangle \right) ,\) which follows a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}\) and covariance \(\varvec{\Sigma }_{\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varvec{\Sigma }_{\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}}&= \left( \langle \lambda \rangle \varvec{\Phi }^\top \varvec{\Phi } + \text {diag}(\langle \varvec{\gamma } \rangle ) \right) ^{-1}, \end{aligned}$$(8)$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\varvec{\alpha }}&= \langle \lambda \rangle \varvec{\Sigma }_{\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}} \varvec{\Phi }^\top \textbf{B}. \end{aligned}$$(9) -

2.

Noise precision \(\lambda\): \(b(\lambda )\) follows a Gamma distribution with mean:

$$\begin{aligned} \langle \lambda \rangle = \frac{M + c}{\left\langle \Vert \textbf{B} - \varvec{\Phi } \varvec{\alpha }\Vert _2^2 \right\rangle + d} , \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(\left\langle \Vert \textbf{B} - \varvec{\Phi } \varvec{\alpha }\Vert _2^2 \right\rangle = \Vert \textbf{B} - \varvec{\Phi } \hat{\varvec{\alpha }}\Vert _2^2 + \textrm{Tr}(\varvec{\Phi } \varvec{\Sigma }_{\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}} \varvec{\Phi }^\top )\), \(c=\)0, \(d=\)0 in implementation.

-

3.

variance and rate parameter \(\varvec{\gamma }, \varvec{\eta }\)29,30: For each component l:

$$\begin{aligned} \langle \eta _l \rangle&= \frac{\epsilon + a_l}{\langle \gamma _l \rangle + b_l} ,\end{aligned}$$(11)$$\begin{aligned} \langle \gamma _l^{-1} \rangle&= \sqrt{ \frac{ \langle |\alpha _l|^2 \rangle }{ \langle \eta _l \rangle } } \frac{ K_{p}\left( 2 \sqrt{ \langle \eta _l \rangle \langle |\alpha _l|^2 \rangle } \right) }{ K_{p-1}\left( 2 \sqrt{ \langle \eta _l \rangle \langle |\alpha _l|^2 \rangle } \right) } , \end{aligned}$$(12)where \(\langle |\alpha _l|^2 \rangle = |\hat{\alpha }_l|^2 + [\varvec{\Sigma }_{\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}}]_{ll}\), \(K_p(\cdot )\) is the modified Bessel function, defined as \(K_p(z) = \int _0^\infty \exp (-z\cosh t)\cosh (pt) dt, p = \epsilon - 1 = -0.9\), which analytically solves for the hyperparameters, thereby accurately capturing the spatial correlation of the light source speckle noise.

-

4.

Output: \(\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}_{\textrm{est}} = \hat{\varvec{\alpha }}^{(T)}\) (sparse coefficients after T VMP iterations), \(\textbf{W}_{\textrm{est}} = \textbf{R} \left( \textbf{D} \hat{\varvec{\alpha }}_{\textrm{est}}\right)\).

Full derivations are provided in Appendix A, and the derivation follows the framework established in References16,24,27,29.

The overall schematic diagram of the reconstruction algorithm based on Sparse representation via KSVD and sparse Bayesian estimation for GI is shown in Fig. 3.

Workflow of the proposed CSGI framework. (Phase 1) KSVD Dictionary Learning (blue), Input: training image patches \(\textbf{Y}\); Process: sparse coding and dictionary update (details in Appendix A.1); Output: dictionary \(\textbf{D}\), sparse codes \(\varvec{\alpha }\). (Phase 2) 3L-Bayesian Reconstruction (green), Input: bucket measurements \(\textbf{B}\) in Eq. (4); Process: initialize and update parameters (details in Appendix A.4-A.7); Output: \(\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}_{\text {est}}\), \(\textbf{W}_{\text {est}} = \textbf{R}(\textbf{D}\hat{\varvec{\alpha }}_{\text {est}})\).

This algorithm differs from natural image denoising in that it is specifically tailored to the GI physical model, which consists of two processes as illustrated in the blue and green boxes in Fig. 3. Its strengths lie in its physical adaptability, achieved through threefold innovations: physical constraint modeling, non-overlapping KSVD acceleration, and ”Gaussian-Gamma-Gamma three-layer” - Bessel VMP noise adaptivity. These innovations significantly enhance computational efficiency, robustness to low sampling, and noise adaptability, as experimentally verified in next Section.

Results

In order to verify the performance of the model we optimized, simulation and experiment are performed. In this process, a simple binary pattern (“double-slit”), a complex pattern of biological tissues (“lung structure”), and a real biological sample (”human blood cell sample”) are selected as target objects. In the experiment, as shown in Fig. 1, the pregenerated speckle patterns are projected onto the transmissive object using a DLP projector. Subsequently, the transmitted light intensity was then collected using a bucket detector (Thorlabs PDA100A2, detected area 75.4 mm\(^2\), gain 70dB) for correlation-based image reconstruction. The double slit pattern was specifically chosen as the test object (with a center-to-center separation of 1 mm and a height of 4 mm) due to fabrication constraints. The variable M is used to represent the number of samples, and the simulation reconstruction results of four reconstruction algorithms are compared (TGI, OMPCSGI, BCSGI and our approach). In order to quantitatively analyze the imaging quality, the PSNR is introduced, which is defined as the ratio of the maximum possible signal power to the reconstruction error power, with the formula described below31

where \(MSE=1/L\sum _{x=0}^{K-1}\sum _{y=0}^{K-1}\left[ R\left( x,y\right) -T\left( x,y\right) \right] ^2\), with R(x, y) and T(x, y) being the original and restored images, respectively, \(\textrm{T}_{\textrm{max}}\) represents the maximum pixel value of the image.

Firstly, the corresponding simulation and experiment results for the binary object “double-slit” are presented in Fig. 4, where each column corresponds to different measurement times (\(M=\) 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000), and each row represents a type of restructuring algorithms (TGI, OMPCSGI, BCSGI and our approach). For ease of comparison, the PSNR (the PSNR is measured in dB) of every restructuring algorithm is marked at the bottom of results. As shown in Fig. 4(a) and (A), the reconstruction result in TGI is barely visible even for the gradual increment in M. For the BCSGI and OMPCSGI, as depicted in the Figs. 4(b)-(c) and (B)-(C), minor discrepancies are observed in the visual angle effects, where quality of image improves as M increases, and upon reaching a value of 1000 for M, both methods are capable of reconstructing a clear “double slit” image. Notably, the PSNR for BCSGI is marginally higher than that for OMPCSGI. By comparing the four algorithms, it can be found that our approach achieves superior reconstruction quality. Specifically, when M equals 200, the background noise of our approach becomes invisible, while the images from the other three algorithms are still overwhelmed by noise. Upon increasing M to 400, which corresponds to a sampling rate below 12.2%, a near-perfect reconstruction is essentially achieved in our model. In summary, both simulation and experimental results indicate that, for simple binary images, our scheme not only provides clearer and more precise reconstructions but also requires a lower sample count for optimal imaging.

Figure 4 showcases the exceptional reconstruction capabilities of our optimized algorithm, without considering the complexity of the patterns or objects involved. Here, we selected “lung structure” as the target object to simulate the highly intricate biological tissue, and the corresponding simulation results are depicted in Figs. 5 (a)-(d). It is shown that the model we designed achieves near-perfect imaging result, even with a sampling rate below 12.2%. BCSGI can only produce images with sub-optimal clarity (PSNR \(=\) 13.3060 dB), at \(M=\) 2000, as shown in Fig. 5(c5). And the results of OMPCSGI, as illustrated in Fig. 5(b5), lags slightly behind BCSGI in both visual quality and numerical metrics (PSNR \(=\) 11.2790 dB). In addition, its implementation requires preset sparsity, which is difficult to achieve in a real biological tissue environment. Given that the coefficients of KSVD sparse representation are sparser and that BCSGI does not need to preset the sparsity level, our optimized algorithm shows superiority in reconstructive performance under conditions of limited sample data, particularly for images rich in edge information. This offers significant theoretical support and potential application value for the identification of complex biological tissues in the biomedical field.

Simulation results of four reconstruction algorithms for (a0) “lung structure” and the corresponding reconstruction for (A0) “real human blood cell sample”. The first to fourth rows of each image set correspond to TGI, OMPCSGI, BCSGI, and our approach, respectively, while each column represents \(M=\) 400, 800, 1200, 1600 and 2000.

To verify the practical applicability and effectiveness of our method in real biological samples, we employ human blood cell sample as target object. The comparative results of the four algorithms are displayed in Figs. 5 (A)-(D). Our algorithm consistently products the best reconstruction results at various sampling rates. Particularly at \(M=\) 400, our method maintains 29.8964 dB PSNR while perfectly conserving the biconcave discoid shapes and cellular edges. In contrast, for OMPCSGI and BCSGI, it is only at \(M=\) 2000, with PSNR values of 22.2858 dB and 23.4151 dB respectively, that BCSGI manages to achieve a slightly clearer image, while the output of OMPCSGI still has artifacts. Notably, TGI shows the poorest performance and failed to effectively reconstruct the image of the original target object. Apparently, among the four evaluated algorithms, our approach not only exhibits superior reconstruction quality but also significantly decreases the required sampling rate for the algorithm.

The corresponding reconstruction results for (a0) “lung structure” and (A0) “real human blood cell sample” under different Gaussian white noise factors when \(M=\) 2000. The first to fourth columns represent the reconstruction results with no-noise, and noise conditions of 25 dB (\(\eta _{a}=5.6\%\)), 20 dB (\(\eta _{a}=10\%\)) and 15 dB (\(\eta _{a}=17.8\%\)).

Then, we take into account the noise robustness of our proposed scheme, various types of path noises are considered, which degrade imaging quality by perturbing the field strength fluctuations detected by the bucket detector. We introduce the noise amplitude ratio (\(\eta _{a}\)) as a metric to transform the traditional signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, \(\eta _a = \sqrt{10^{-SNR/{10}}}\)), directly quantifying field-strength perturbations, where higher \(\eta _{a}\) values indicate stronger noise interference. The corresponding results for complex biological tissue ”lung structure” and ”real human blood cell sample” (\(M=\) 2000) are compiled in Fig. 6, where each column corresponds to a certain degree of noise effect (column 1: no-noise, column 2-4: noise conditions of 25 dB (\(\eta _{a}=5.6\%\)), 20 dB (\(\eta _{a}=10\%\)) and 15 dB (\(\eta _{a}=17.8\%\)), respectively), and each row corresponds to a kind of algorithms (TGI, OMPCSGI, BCSGI and our approach). It is evident that, with the escalation of noise levels, the PSNR of each method undergoes a decrease, while our approach exhibits remarkable noise resistance, boasting the highest PSNR of the four algorithms, which indicates that our approach performs strong noise resistance while presents better imaging quality even under the noise conditions of 15 dB (\(\eta _{a}=17.8\%\)). However, higher levels of noise (\(\eta _{a}\ge 15\%\)) can interfere with the KSVD algorithm’s ability to sparsely represent the signal, thereby affecting the accuracy of the dictionary update, which may lead to the ”block effect” in the reconstructed image, as shown in Figs. 6 d(4) and D(4). In addition to that, considering complexity and realism, our approach performs best in path noise environments, particularly with Gaussian white noise.

The corresponding reconstruction results of four algorithms for two objects under different multiplicative noise levels. The parameters are the same as those in Fig. 6.

To demonstrate the universality of our approach, Gaussian white noise is replaced with multiplicative noise to assess the noise resistance of four GI methods under different degrees of noises when \(M=\) 2000. The effect of multiplicative noise is distinct from that of Gaussian white noise, it is more complex as it can affect not only the amplitude but also the shape and characteristics of the signal. The corresponding results are depicted in Fig. 7. It becomes evident that as the noise levels increase, the PSNR of each system decreases, with a greater extent than that observed under the influence of Gaussian white noise. It is worth noting that, whether for complex patterns or real biological samples, when \(\eta _{a}\ge 10\%\) (equivalent to 20 dB), GI, OMPCSGI, and BCSGI are particularly susceptible to multiplicative noise interference, which can nearly submerge the images, while our method retains a relatively stable reconstruction capability. However, as shown in Figs. 7 d(4) and D(4), under the influence of higher levels of multiplicative noise (\(\eta _{a}=17.8\%\)), more pronounced structural breaks are evident compared to the Gaussian white noise depicted in Figs. 7 d(4) and D(4). For such significant multiplicative noise interference, effective solutions may be achieved in the future through the application of deep learning (such as Graph Convolutional Networks) or optical path correction techniques.

To objectively and accurately evaluate the capabilities of different algorithms in terms of image reconstruction accuracy, the reconstruction accuracy can be evaluated by computing the correlation coefficient (\(r_{TG}\)) and structure similarity index measure (SSIM) between the reconstructed image G and the original image T. \(r_{TG}\) is a linear description of the degree of approximation between the two images, whereas SSIM provides a more holistic assessment by taking into account luminance distortion, contrast distortion, and structural distortion. Higher values of these evaluation metrics indicate superior image quality, with the maximum attainable value being 1 for both indices. The calculation formulas for \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM are as follows32:

where D(T) and D(G) are the variance of the T and G, respectively. E(T) and E(G) are their means. \(\sigma _{TG}\) is the covariance between T and G, \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are constants to prevent the denominator from approaching 0.

The variation curves of \(r_{TG}\) for above three target objects under different measurement samples are illustrated in Figs. 7(a)-(c), and their corresponding SSIM curves are presented in Figs. 8(d)-(e), respectively. Each curve in these sub-plots corresponds to a different algorithm, with TGI illustrated in black, OMPCSGI in blue, BCSGI in red, and our scheme in green. It is easy to find that all three graphs demonstrate that when \(M=\) 500, the reconstruction effects for three target objects of our optimized model become extremely outstanding, achieving near-perfect results with \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM are almost equal to 1. In Figs. 8(a) and (d), for the binary object “double-slit”, the \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM of the our approach increases rapidly (\(r_{TG}\) and SSIM are equal to 1 at \(M=\) 400), while the values of \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM for TGI, BCSGI and OMPCSGI are difficult to reach 1 and achieve the perfect reconstruction, even if M increases to 1000. Especially for the complex images and the real blood cell sample displayed in Figs. 8(b), (e) and Figs. 8(c), (f), respectively, the values of \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM of reconstructed images for our approach consistently maintain a value of 1. In contrast, the SSIM values for both BCSGI and OMPCSGI are fall below 0.8 at \(M=\) 2000. This disparity sufficiently demonstrates the superior reconstruction performance of our method.

To quantify the anti-noise capabilities and the precision of image recovery for four algorithms, the \(r_{TG}\) curves (Figs. 9 (a)-(d)) and SSIM curves (Figs. 9 (e)-(f)) for complex object and real biological sample under above two types of noises are presented in Fig. 9. The first and third columns correspond to Gaussian white noise, while the second and fourth columns correspond to multiplicative noise. Each curve of different colors corresponds to different methods (with TGI illustrated in black, OMPCSGI in blue, BCSGI in red, and our scheme in green). It is evident that as the \(\eta _{a}\) increases, the system becomes increasingly susceptible to noise interference, leading to a decline in both \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM of the reconstructed image. Figures 9(a) and (e) display the reconstruction results (when \(M=\) 2000) of the ”lung structure” object under different varying levels of Gaussian white noise. Obviously, \(r_{TG}\) values in Fig. 9(a) of our approach are always higher than those of others, and the SSIM curves depicted in Fig. 9(e) reflect the same conclusion. This suggests that our approach significantly reduces the adverse effects of Gaussian white noise. As depicted in Figs. 9 (c) and (g), the same conclusion can be drawn for ”real human blood cell sample”. When accounting for multiplicative noises, whether it is a complex object or a real biological sample, both \(r_{TG}\) and SSIM curves drop sharply as the noise increases. In particular, when the noise ratio \(\eta _{a}\ge 15\%\), although our method still outperforms other algorithms, it is also significantly affected in terms of structural integrity. Consequently, our algorithm demonstrates strong robustness against Gaussian white noise and medium-to-low levels of multiplicative noise. For higher levels (\(\eta _{a}\ge 15\%\)) of non-uniform multiplicative noise, to avoid structural discontinuities (”block effects”), future work could consider integrating deep learning to mitigate the noise-induced damage to the original signal.

For compressive sensing algorithms, the time consumption of the algorithm is an important evaluation criteria. Subsequently, the issue of time consumption is discussed. For existing BCSGI, due to the complex posterior probability calculations involved in Bayesian estimation, it tends to show higher time complexity, especially when dealing with large-scale data. In contrast, our method, by integrating KSVD, optimizes the iterative process, ensuring that the algorithm maintains high imaging accuracy while appropriately reducing computational time. Figure 10 illustrates the time consumption curves for the above three target objects of both BCSGI and our optimized approach, with the red line representing BCSGI and the green line representing our algorithm. It is shown that the time consumption increases with the growth of M, yet our algorithm consistently shows lower time consumption compared to the existing BCSGI. Particularly, for complex target objects and real blood cell sample with \(M>\)1200, as depicted in Figs. 10 (b) and (c), the time consumption exceeds 30 seconds. Conversely, the KSVD algorithm, as shown by the green curves in the three figures, enables our method to achieve a balance between maintaining reconstruction accuracy and moderately reducing the algorithm’s time consumption through its iterative optimization process. Nevertheless, future research should still focus on the time efficiency of algorithm to further optimize the running time of algorithm while ensuring the quality of reconstruction is maintained.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have proposed an anti-noise variational sparse Bayesian estimation CSGI based on 3Level factor graph for the imaging of complex biological tissues at low sampling rates. Comparative analysis reveals that our algorithm surpasses other traditional methodologies in reconstruction quality and anti-noise capability under lower sampling rate, especially for images with complex edge details, indicating near-perfect reconstruction at a low sampling rate (below 12.2%). In addition, compared to existing BCSGI, our approach appropriately reduces the time consumption. These advancements address the practical challenge that the sparsity of traditional CSGI algorithm cannot be preset, which is conducive to the popularization of biomedical imaging applications. And subsequent research can integrate deep learning to address the issue of imaging structural breaks (“block effect”) under significant noise influence.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pittman, T. B., Shih, Y., Strekalov, D. & Sergienko, A. V. Optical imaging by means of two-photon quantum entanglement. Phys. Rev. A. 52, R3429. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.52.R3429 (1995).

Xiong, J. et al. Experimental observation of classical subwavelength interference with a pseudothermal light source. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 173601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.173601 (2005).

Zhai, Y.-H., Chen, X.-H., Zhang, D. & Wu, L.-A. Two-photon interference with true thermal light. Phys. Rev. A. 72, 043805. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.72.043805 (2005).

Shapiro, J. H. Computational ghost imaging. Phys. Rev. A. 78, 061802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.78.061802 (2008).

Ferri, F., Magatti, D., Lugiato, L. & Gatti, A. Differential ghost imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 253603. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.253603 (2010).

Sun, B., Welsh, S. S., Edgar, M. P., Shapiro, J. H. & Padgett, M. J. Normalized ghost imaging. Opt. Express 20, 16892–16901. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.20.016892 (2012).

Zhang, C., Guo, S., Cao, J., Guan, J. & Gao, F. Object reconstitution using pseudo-inverse for ghost imaging. Opt. Express 22, 30063–30073. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.22.030063 (2014).

Lyu, M. et al. Deep-learning-based ghost imaging. Sc. Rep. 7, 17865. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18171-7 (2017).

Katz, O., Bromberg, Y. & Silberberg, Y. Compressive ghost imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 131101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3238296 (2009).

Li, F., Triggs, C. M., Dumitrescu, B. & Giurcaneanu, C. D. The matching pursuit algorithm revisited: A variant for big data and new stopping rules. Signal Process. 155, 170–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2018.09.033 (2019).

Lv, S., Man, T., Zhang, W. & Wan, Y. High quality underwater computational ghost imaging based on speckle decomposition and fusion of reconstructed images. Opt. Commun. 561, 130460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2024.130460 (2024).

Wipf, D. P. & Rao, B. D. Sparse bayesian learning for basis selection. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 52, 2153–2164. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2004.831016 (2004).

Babacan, S. D., Nakajima, S. & Do, M. N. Bayesian group-sparse modeling and variational inference. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62, 2906–2921. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2014.2319775 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Ghost imaging with bayesian denoising method. Opt. Express 29, 39323–39341. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.438478 (2021).

Zhang, Z. & Rao, B. D. Extension of sbl algorithms for the recovery of block sparse signals with intra-block correlation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 61, 2009–2015. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2013.2241055 (2013).

Serra, J. G., Testa, M., Molina, R. & Katsaggelos, A. K. Bayesian K-SVD Using Fast Variational Inference. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26, 3344–3359. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2017.2681436 (2017).

Aharon, M., Elad, M. & Bruckstein, A. K-svd: An algorithm for designing overcomplete dictionaries for sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 54, 4311–4322. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2006.886303 (2006).

Heskes, T., Opper, M., Wiegerinck, W., Winther, O. & Zoeter, O. Approximate inference techniques with expectation constraints. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2005, P11015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2005/11/P11015 (2005).

Dauwels, J. On variational message passing on factor graphs. In 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, 2546–2550, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10883-005-4175-9 (IEEE, 2007).

Xing, E. P., Jordan, M. I. & Russell, S. A generalized mean field algorithm for variational inference in exponential families. arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.2512https://doi.org/10.5555/2100584.2100655 (2012).

Liu, J., Zhang, E., Liu, W. & Zhu, J. Multi-receivers and sparse-pixel pseudo-thermal light source for compressive ghost imaging against turbulence. Inverse Probl. Sci. Eng. 24, 901–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/17415977.2015.1101759 (2016).

Ma, P., Meng, X., Liu, F., Yin, Y. & Yang, X. Singular value decomposition compressive ghost imaging based on multiple image prior information. Opt. Lasers Eng. 182, 108471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2024.108471 (2024).

Han, S. et al. A review of ghost imaging via sparsity constraints. Appl. Sci. 8, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8081379 (2018).

Lesage, S., Gribonval, R., Bimbot, F. & Benaroya, L. Learning unions of orthonormal bases with thresholded singular value decomposition. In Proceedings.(ICASSP’05). IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 2005., vol. 5, v/293–v/296 Vol. 5, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2005.1416298 (IEEE, 2005).

Zhu, R., Li, G. & Guo, Y. Compressed-sensing-based gradient reconstruction for ghost imaging. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 58, 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-019-04013-x (2019).

Pedersen, N. L., Manchón, C. N. & Fleury, B. H. A fast iterative bayesian inference algorithm for sparse channel estimation. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 4591–4596, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2013.6637886 (IEEE, 2013).

Winn, J., Bishop, C. M. & Jaakkola, T. Variational message passing. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 6, 661–694. https://doi.org/10.5555/1046920.1088695 (2005).

Wang, C., Li, Z.-Y. & Huang, L. Sparse channel estimation based on improved bp-mf algorithm in sc-fde system. In 2017 International Conference on Computer Systems, Electronics and Control (ICCSEC), 1065–1069, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCSEC.2017.8446928 (IEEE, 2017).

Pedersen, N. L., Manchón, C. N., Shutin, D. & Fleury, B. H. Application of bayesian hierarchical prior modeling to sparse channel estimation. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 3487–3492, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2012.6363847 (IEEE, 2012).

Jørgensen, B. Statistical properties of the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution (Statistical Properties of the Generalized Inverse Gaussian Distribution) (Statistical Properties of the Generalized Inverse Gaussian Distribution, 1982).

Zhu, R., Li, G.-S. & Guo, Y. Block-compressed-sensing-based reconstruction algorithm for ghost imaging. OSA Continuum 2, 2834–2843. https://doi.org/10.1364/OSAC.2.002834 (2019).

Tan, S., Sun, J., Tang, Y., Sun, Y. & Wang, C. Hyperchaotic bilateral random low-rank approximation random sequence generation method and its application on compressive ghost imaging. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 5749–5763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-09317-0 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study received formal ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Biomedical Sciences Hunan University (Approval date: March 2025). Human blood samples used in this study were voluntarily donated by the research team for scientific purposes, in accordance with international ethical standards for self-experimentation. All participants provided written informed consent covering sample usage and data publication, and procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62301217).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Q.X., X.F.Q., and Y.F.B. conceptualized the study; Q.Z. and J.X.C. developed the methodology; S.Q.X., T.F.L., and X.L. conducted the experiments; Q.Z., Y.F.B., J.Q.Y., J.T.Z., and X.W.H. prepared the original draft; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, S., Bai, Y., Zhou, Q. et al. Anti-noise variational sparse Bayesian estimation ghost imaging based on 3Level factor graph. Sci Rep 15, 44734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28476-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28476-7