Abstract

Geopolymer solidified soil has been extensively studied and however, knowledge gaps exist regarding the long-term influence of temperature and its modelling on the strength characteristics of geopolymer solidified soil. Fly ash (FA), calcium carbide residue (CCR) and NaOH are among the most widely investigated precursor and activator materials. Owing to their excellent performance, a CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer is adopted as the binder in this research. An attempt is made to investigate the long-term influence (7, 14, 28, 60, 90, 150, 180, 240 days) of temperature (20 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C) on strength of solidified marine soft clay. Strength calculation model regarding long-term temperature influence is proposed, modified and established. The model accuracy is verified and deviation between true and predicted values is within approximately 10%. The 7-day strength of the specimen cured at 40 °C reaches 2352.5 kPa, which is 2.44 times that of the specimen cured at 20 °C. Strength improvement index (SI) of temperature is defined, indicating that higher curing temperatures correspond to greater SI values. Surface microgram is obtained by scanning electron microscope, and the stabilization and temperature influence mechanisms are discussed. Strength development is mainly attributed to pore filling, cementitious products and ion exchange. Higher curing temperatures enhance the chemical reaction rate, promoting the generation of more cementitious products. The experimental results can provide theoretical guidance for achieving the target strength of geopolymer solidified soil under long-term temperature influence in engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of urbanization, the available land resources have been steadily decreasing. To meet development demands, it has become essential to explore alternative resources. On the other hand, costal area is surrounded by marine soft clay and its significant features are high porosity, high water content, low permeability, high compressibility and low strength1. In China, enormous expenditures are incurred annually to remove and treat the marine soft clay2. Traditional treatment methods are being increasingly restricted due to environmental concerns. In recent years, various techniques such as dynamic compaction and soil replacement have been employed for the treatment of soft clay3,4,5. Among these, soil stabilization technique has remained one of the most widely used and it has a relatively long history6. Chemical stabilization, a method of soil stabilization technique, is commonly used method, which is achieved by mixing soft soil with cementitious materials. These materials include cement, lime, FA, CCR, cement kind ash, copper slag, ground granulated blast-furnace slag, recycled bassanite, glass powder and nano-SiO27,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. When introduced into clay soil, a series of chemical and physical reactions occur, forming cementitious products that fill the pores and bind soil grains19. Consequently, the strength is improved. Among the various stabilising agents, cement remains the most common materials owing to its reliable performance. When added to clay soil, hydration reaction first occurs and the CSH, CAH and calcium hydroxide are formed, which is in favor of strength development20. The calcium hydroxide can react with active mineral containing silicon or aluminum of clay and also form CSH and CAH, which is responsible for later strength development21. Moreover, the calcium ions formed in the reaction can exchange with sodium ions on soil surface, leading to a reduction in the thickness of the diffuse double layer and promoting flocculation of soil particles22. However, because of the high carbon emissions and energy consumption, associated with cement production, its widespread application has been restricted in recent years. This has created an urgent need for sustainable alternative materials.

Geopolymer (Fig. 1), formed through the chemical reaction between precursor containing aluminum or silicon and alkali, a material possessing the characteristics of green, low-carbon, environmentally friendly, efficient and excellent durability. In recent years, geopolymer technology has emerged as a promising alternative to conventional binders, and its application in soil stabilisation has gained considerable attention. Phummiphan et al.23 utilised CCR and FA for stabilizing marginal lateritic soil, demonstrating that the soaked 7-day strength of sample meets the traffic pavement strength requirement. Horpibulsuk et al.24 confirmed that the CCR-FA can be used as an alternative to cement to act as a soil stabilizer. Zhu et al.25 investigated the mechanical property of CCR-FA-marine soft clay and it found that composite agent solidified soil met the specified requirements for roadbed filler. Siddiqua and Barreto26 reported considerable strength enhancement when CCR and FA were used to stabilise rammed earth and it shows a significant strength growth. Wang et al.27 investigated the mechanical properties of CCR-FA-waste mud and it revealed that the sample had a promising application prospect in subgrade engineering projects. From these studies, it is evident that the CCR-FA-solidified soil has excellent mechanical properties. Therefore, in the present research, the CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer was selected for solidifying marine soft clay, offering both scientific and practical importance.

The mechanical properties of solidified soil are influenced by various factors, including water contents, stabilizer contents, and curing time28,29,30. Moreover, geotechnical structures are often exposed to different temperature environments and the temperature is also one of the most important influencing factors. Therefore, it is of great significance and value to explore the influence of temperature on the properties of solidified soil. It has been investigated by previous researches and has achieved notable findings. For solidified soil with conventional stabilizer such as cement or lime, Al-Mukhtar et al. (2010) investigated the behaviour of lime-solidified expansive soil at 50 °C and the pozzolanic reaction is accelerated at higher temperature, which leads to the strength development of solidified soil31. Bao et al.32 studied the strength evolution of lime-solidified loess under high-temperature and the result demonstrated that the shear and compressive strengths of samples treated for high-temperature both had an improvement. Bi and Chian33 explored the strength evolution of cement‑solidified soil with different temperatures and the result found that the effect of temperature on strength characteristic mainly depends on the presence of fine-grained clay particles and increased strength-enhancing materials in cement-soil system. Lu et al.34 analysed the shear characteristic of cement-solidified silty clay under low-temperature curing and it observed that the cohesion and shear strength were both improved with temperature. Bache et al.35 investigated the effect of temperature on strength evolution of cement-lime solidified Norwegian clays and the result demonstrated that increasing temperature is beneficial to obtaining higher shear strength values and strength development. Yun et al.36 reported that the higher curing temperature can lead to strength development of cement-modified soils. Cai et al.37 presented the strength development of cement-solidified soil at varied temperatures and the unconfined compressive strength of samples was improved with the increment of temperatures. Zhang et al.38 also indicated that the increasing curing temperature resulted in strength development of cement-solidified clay.

For solidified soil with geopolymer or other materials, the temperature effect is also investigated by previous researches. Salimi and Ghorbani39 explored the effect of temperature on strength properties of slag-based geopolymers solidified soft clay and the result showed that the increasing temperature is beneficial to the faster formation of gelling products, which results in a higher unconfined compressive strength value. Liu et al.40 evaluated the mechanical properties of metakaolin based geopolymer or cement solidified soil and it indicated that when the curing temperature decreases, the UCS of geopolymer solidified soil also decreases. Compared to cement treated soil, the geopolymer treated soil has excellent mechanical properties at low temperature due to denser microstructure and hydration products38. Phetchuay et al. (2016) evaluated the effect of temperature (25 and 40 °C) on strength development of fly ash-calcium carbide residue based geopolymer treated soil and the increasing temperature is beneficial to geopolymerization reaction, which can significantly improve the unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil15. Mohammadinia et al.41 explored the properties of fly ash-crushed brick- reclaimed asphaltin and the higher temperature (40 °C) is beneficial to strength development of samples. Bilondi et al.42 presented the experimental results of solidified soil with recycled glass powder-based geopolymer and it indicates that the increasing temperature from 25 to 70 °C can significantly enhance samples strength. Sabrin et al.43 revealed the influence of temperature (40, 60, 80 °C) on solidified subgrade soil with bentonite and magnesium alkalinization and it shows that the desirable strength cured at ambient temperature or 40 °C is not achieved, but increasing temperature is in favor of the strength development. Wang et al.44 investigated the leachability and durability of GGBS-MgO-CaO treated Pb/Zn contaminated soil with different curing temperature and the increasing temperature is beneficial to the increase of durability and leachability. For the strength calculation model of temperature effect, on the basis of Arrhenius equation, Chitambira45 established a calculation model for the strength of cement-stabilized granular soil as it changed with temperature. Based on the experimental results of five different samples of Singapore marine clay solidified with cement, Zhang et al.38 developed a strength calculation model that takes into account the effect of temperature. It is concluded from above analysis that some achievements have been made in the research of temperature effect. However, the main focus of the research is on the impact of temperature on the properties of cement-stabilized soil. For the temperature effect on geopolymer treated soil, the curing time is usually short (≤ 28 days). Strength development models considering the long-term influence of temperature have rarely been reported. The influence of temperature on the properties of geopolymer-cementitious soil can not be fully revealed. Therefore, in this research, the long-term influence (cured for 180 or 240 days) of temperature on mechanical property of fly ash-calcium carbide residue geopolymer solidified marine soft clay is explored and analyzed.

The purpose of this research is to investigate the long-term temperature influence (7, 14, 28, 60, 90, 150, 180, 240 days) on strength properties of calcium carbide residue-fly ash-NaOH geopolymer solidified marine soft clay. The variations of solidified soil strength with water contents, curing temperature and curing time are investigated. The improvement index of temperature is defined and its values under different temperatures are analyzed. The unconfined compressive strength calculation model regarding the long-term influence of temperature is proposed, modified and established and the calculation accuracy is verified. Scanning electron microscope test is adopted for obtaining microscopic image of samples. Finally, the stabilization mechanism of fly ash-calcium carbide residue geopolymer and long-term influence mechanism of temperature are both discussed and analyzed in this research.

Experimental materials and methods

Experimental materials

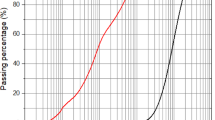

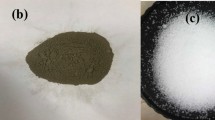

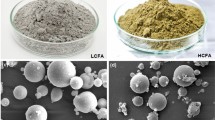

Soil sample selected for experimental tests in this study is marine soft clay collected from Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China. Its physical parameters are listed in Table 1. The liquid-plastic limits are tested according to the ASTM D4318 and the result is presented in Table 146. Soil sample belongs to a low-plasticity clay (CL) on the basis of ASTM D248747. The microscopic photo and chemical composition of marine soft clay are shown in Fig. 2; Table 2, respectively. Its microscopic morphological features show a sheet-like and irregular shape. The particle size distribution curve is presented in Fig. 3. Fly ash, CCR and NaOH are among the most widely investigated precursor and activator materials and based on their excellent performance, the calcium carbide residue-fly ash-NaOH geopolymer are adopted for binder in this study. The CCR was sourced from Yantai City, Shandong Province, China, while FA was from Shijiazhuang City, Hebei Province, China. Their oxide compositions are concluded in Table 2. It can be observed that the main compositions of clay and FA are both SiO2 and Al2O3. The soil also contains a certain amount of chloride ions. But the main composition of calcium carbide residue is CaO. The microscopic image and particle size distribution curve of CCR and FA are presented in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The microscopic morphological feature of CCR show a sheet-like and irregular shape. But the FA exhibits a spherical shape. It can be concluded from Fig. 3 that the particle size distribution characteristics of clay, CCR and FA are similar. Overall, the particle size of fly ash is the smallest, followed by soil, and that of calcium carbide slag is the largest. Sodium hydroxide is chemically pure.

Specimen preparation

To study the influence of temperature on the properties of solidified soil, the process of sample preparation was as following: The marine soft clay was broken into small pieces with a leather hammer and sieved with a 2-mm sieve, followed by drying in the oven. The weighed CCR and FA were both added into clay soil in dry condition. NaOH was dissolved in water and then it was mixed with the above dry mixture well. The cylindrical mold (diameter of 3.91 cm and height of 8 cm) was adopted for holding specimens. A sample was packed into the mold in three times and regular vibration was applied during sample preparation to exclude bubbles. The specimen was placed in the curing room (at different temperatures) for specific curing time. To ensure the experimental results credibility, three parallel samples were prepared with the same content. The ZD/WDW-300 M was used for unconfined compressive strength testing and vertical displacement of 1.0 mm/min was adopted. The chemical composition and microscopic image of samples were obtained by X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) test and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), respectively. The Panalytical Axios was used for conducting chemical composition tests. The ZEISS Sigma 300 was adopted for obtaining the microscopic morphological features. Before conducting the experimental test, the sample needed to be treated with gold plating. The experimental designs are listed in Table 3. The FA and CCR contents were both 8%. Based on the previous researches, the NaOH content was 1%48,49. The addition contents of CCR, FA and NaOH are all in the ratio to dry soil and they are constant in this research. The schematic diagram of specimen preparation is presented in Fig. 4.

Test results and analysis

Unconfined compressive strength

Influence of water contents on unconfined compressive strength

The relationship between water contents and unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil at different curing time is concluded in Fig. 5a–d. Overall, sample strength gradually decreases with water contents. For instance, when the curing time is 7 days and water content is 57.4%, the solidified soil strength cured for 20 °C is 834.81 kPa, as presented in Fig. 5a. When the water content is 73.8%, the unconfined compressive strength is 269.22 kPa. It accounts for only 32.25% of the modified soil strength with 57.4% water content. When the curing time is 90 days and water content is 49.2%, the solidified soil strength cured for 20 °C is 2724.87 kPa, as presented in Fig. 5c. When the water content is increased to 82%, the unconfined compressive strength drops to 511.17 kPa. It accounts for only 18.76% of the modified soil strength with 49.2% water content. The sample strength at other curing times varies with water content in the same way as that at the curing time of 7 or 90 days, as presented in Fig. 5a–d. The increase of water content means the relative decrease of binder content and it leads to the reduction of gelling products. The soil grains cannot be cemented effectively and the sample porosity is relatively large. Based on it, the strength of CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer treated soil gradually decreases with increasing water contents.

Influence of curing time on unconfined compressive strength

The variations of treated soil with different curing time are summarized in Fig. 6a–d. It is evident that the curing time has a positive effect on CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer treated soil strength and it gradually increases with curing time. However, the rate of increase gradually diminishes at longer curing durations. For instance, when the water content is 49.2% and the curing temperature is 20 °C, the 7-day sample strength is 922.08 kPa, as presented in Fig. 6b. The strength of solidified soil cured for 150 days is 3418.87 kPa and it is 270.8% higher than the 7-day strength. when the water content is 73.8% and the curing temperature is 20 °C, the 7-day sample strength is 224.21 kPa, as presented in Fig. 6c. The strength of solidified soil cured for 150 days is 978.56 kPa and it is 336.4% higher than the 7-day strength. The sample strength with other water contents varies with curing time in the same way as that of 49.2% or 73.8% water content. When the curing time increases, the ion exchange reaction and pozzolanic reaction gradually occur after the incorporation of CCR and FA. The gelling chemical products are formed, and it can bond soil grains. The ion exchange reaction is beneficial to particle flocculation and double electric layer thickness reduction. Therefore, the CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer treated soil strength improves with curing time.

Influence of curing temperature on unconfined compressive strength

The influence of curing temperature on unconfined compressive strength of CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer solidified soil under various curing time and water contents is concluded in Fig. 7a–g. The curing temperature has a positive effect on treated soil strength and the strength gradually increases with increasing curing temperature. When the water content is 65.6% and curing time is 28 days, the solidified soil strength cured for 20 °C is 1155.215 kPa, as listed in Fig. 7d. The sample strength cured for 40 °C is 1818.727 kPa and it is 57.4% higher than the 20 °C strength. When the water content is 82% and curing time is 60 days, the solidified soil strength cured for 20 °C is 490.46 kPa, as listed in Fig. 7f. The sample strength cured for 40 °C is 947.19 kPa and it is 93.1% higher than the 20 °C strength. The treated soil strength with other water contents varies with curing temperature in the same way as that of 65.6% or 82% water content. When the curing temperature gradually increases, the chemical reaction rate is improved35. The increasing temperature is beneficial to geopolymerization reaction and pozzolanic reaction, which can result in more gelling products formation15,31. The soil grains can be cemented and it is in favor of the formation of three-dimensional soil skeleton structure. Consequently, the unconfined compressive strength is improved with increasing temperature.

Influence of curing temperature on strength improvement index

In order to more intuitively show the temperature effect, the strength improvement index (SI) is defined in this research and its relational expression is presented in Eq. (1). The relationship between SI and curing temperature is concluded in Fig. 8a–g. The strength improvement index gradually improves with the curing temperature. For example, when the curing time is 28 days and the water content is 57.4%, the strength improvement index of sample cured for 20 °C is 1, as shown in Fig. 8c. The strength improvement index cured for 40 °C is 1.48 and it is 48% higher than that of sample cured for 20 °C. The strength improvement index with other water contents varies with curing temperature in the same way as that of 57.4% water content. The increasing curing temperature is beneficial to the improvement of chemical reaction rate, geopolymerization reaction and pozzolanic reaction15,31. The more gelling chemical products are formed and the SI value increases with curing temperature. Additionally, the strength improvement index of solidified soil cured for 7 days is the largest. For example, the SI value of sample with 65.6% water content and cured for 40 °C is 2.89, as presented in Fig. 8d. The strength improvement indexes of sample under other water contents are all equal to or greater than 2.5. It can be inferred that the temperature has a significant effect on the improvement of 7-day strength and it is in favor of early strength development of CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer.

Where the SI is strength improvement index; qu, T is the unconfined compressive strength of treated soil cured for T °C; qu,20 is the unconfined compressive strength of treated soil cured for 20 °C.

Long-term strength calculation model with temperature influence

Model proposal

In this research, the variation of solidified soil strength at the 20 °C with curing time is described by hyperbolic model50, as expressed in Eq. (2).

Where t is the curing time; qu is the unconfined compressive strength; a is the inverse of the tangent slope of the curve at zero; b is the inverse of the maximum value of the curve. The expression results of solidified soil strength with curing time at 20 °C are presented in Fig. 9. It can be observed that the Eq. (2) can be adopted for calculating the FA-CCR geopolymer treated soil strength at 20 °C and different curing time.

Model modification

Although the Eq. (2) can express the strength development of treated soil at 20 °C relatively well, the strength evolution law with curing time at other temperature (30 or 40 °C) can not be described. The values of a and b affect tangent slope and maximum value of curve and therefore, it is associated with temperature. The Eq. (2) can be rewritten as follows:

Where θ is rate correction index; β is strength correction index. The function image of Eq. (3) under different θ and β values is presented in Fig. 10. It can be observed that the tangent slope and maximum value of curve both gradually increase with decrease in θ and β values, respectively.

The function image of Eq. (3).

Model building

The expression results of solidified soil strength with curing time at 30 or 40 °C are presented in Fig. 11. By adjusting θ and β values, the description of solidified soil strength at different temperatures can be realized. Therefore, the Eq. (3) is suitable for expressing the relationship between strength at 30 or 40 °C and curing time. It is noted that when the values of θ and β are both 1, the solidified soil strength at 20 °C can be described. In this research, the all θ and β values of solidified soil with different water contents and curing time are concluded in Table 4.

The variation of θ or β with temperature is concluded in Fig. 12. Both parameters exhibit a decreasing trend with increasing temperature. In this research, the following equations are used for describing the relationship between θ or β and temperature and the expressions are shown in Eqs. (4) and (5) (Fig. 13).

The values of k1 and k2 of solidified soil with different water contents are concluded in Fig. 14. After removing the outliers, the relationship between k1 or k2 and water-binder ratio (wc/C) is also presented in Fig. 14. The value of k1 gradually improves with increasing water-binder ratio. The value of k2 gradually decreases with increasing water-binder ratio. The expressions are shown in Eqs. (6) and (7).

Combining Eqs. (3)–(7), the Eq. (3) can be rewritten as follows:

The final strength calculation model of FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay regarding the long-term influence of temperature is established in this research.

Model verification

The strength development model of FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay regarding the long-term influence of temperature has been established in this study, as expressed in Eq. (8). To carry out the precision verification of strength development model, the experiments of solidified soil with 69.4% water content cured for 20 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C were conducted. The comparative analysis between the measured strength obtained from laboratory experiments and calculated strength from strength development model proposed in this study is performed and the result is shown in Fig. 15. It can be observed that the deviation between measured strength and calculated strength is generally within 10%, demonstrating that the strength development model proposed in this research is suitable for quantitatively analyzing the long-term influence of temperature on FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay.

Scanning electron microscope

To evaluate the influence of temperature on microstructure of FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay, the scanning electron microscope test was conducted. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 16. When the water content is 73.8% and the temperature is 20 °C, the microscopic photo is shown in Fig. 16a. It can be observed that the porosity is relatively large and a small amount of gelatinous materials are observed, as shown in Fig. 16a. The microstructure image of specimen cured in 40 °C is presented in Fig. 16b and the porosity is small. The dense microstructure is found and a certain amount of gelatinous material is observed, which is in favor of the strength development of FA-CCR treated marine soft clay. When the water content is 57.4% and temperature is 20 °C, the sample microgram is shown in Fig. 16c. Compared with Fig. 16a, the gelatinous material content increases with the decrease in water content, which is in favor of strength development. Figure 16d presents the microstructure photo of sample cured in 40 °C and it can be observed that the small porosity, dense structure and the formation of gelatinous material are the main reason for strength development. Compared to Fig. 16c, the increase of temperature leads to formation of cluster-like gelling material, as presented in Fig. 16d. Therefore, when the temperature increases, the strength of FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay is improved in this research.

Discussions

From the experimental results presented above, it can be concluded that the strength of FA-CCR geopolymer solidified marine soft clay is significantly influenced by water content, curing time and curing temperature. For example, when the water content changes from 49.2% to 90.2%, the strength decreases from 2596.47 kPa to 385.01 kPa (cured for 60 days). Horpibulsuk et al. (2013) investigated the strength development of CCR-FA stabilized silty clay and it reported that the 28-d strength can exceed 6000 kPa with 5% CCR and 10% FA24. Zhu et al.25 explored the mechanical property of CCR-FA solidified marine soft clay and it demonstrated that 7-d strength of CF-1 solidified soil was 501 kPa. Siddiqua and Barreto26 examined the strength performance of rammed earth solidified with CCR and FA and it demonstrated that when the CCR: FA is 40:60 and binder content is 12%, the 28-d compressive strength can exceed 3 MPa. In this research, after the incorporation of CCR into clay soil, the CaO from CCR can react with water and the reaction equation is shown in Eq. (9). The formed Ca(OH)2 can react with SiO2 and Al2O3 from FA and clay and the equations are shown in Eqs. (10) and (11).

The CSH and CAH with gelling properties are formed, which can cement soil grains and fill the pores. A three-position network structure is formed and it can effectively resist changes in external loads. In addition, NaOH raises the pH value of system and is more conducive to promoting the occurrence of chemical reactions between CCR and FA. Consequently, the strength gradually increases after the incorporation of CCR, FA and NaOH. To intuitively show the reaction mechanism, the schematic diagram of stabilization process with CCR and FA is presented in Fig. 17. Yuan et al. (2025) investigated the coupling effect of cement and alkaline solution in solidifying granite residual soil and it found that the enhancement of mechanical properties was attributed to pore filling and granite residual soil connection through the C-(A)-S-H gels51. Additionally, Yuan et al. (2024) explored the mechanical performance of engineering muck-based geopolymers under different SiO2/Na2O and the liquid–solid ratio and it demonstrated that when the SiO2/Na2O ratio was 1.5, highest 7-day compressive strength of 42 MPa is obtained52. Owing to high reactivity, abundance of clay minerals and little harmful substances, engineering muck is an ideal geopolymers precursor52.

The calcium ion released from Ca(OH)2 can exchange with sodium and potassium ions of clay and it leads to double electric layer thickness reduction, which is beneficial to particle flocculation. The schematic diagram is presented in the Fig. 18. Another key factor contributing to the development of a denser microstructure is the pores filling. The particles from FA and CCR can fill the pores of marine soft clay after the incorporation of CCR and FA, which is beneficial to the mechanical properties development of solidified soil. The schematic diagram is shown in the Fig. 19.

When the FA-CCR-NaOH geopolymer solidified marine soft clay is cured in 20 °C, the aforementioned reactions all exist. The mechanical properties of solidified soil are improved and strength gradually increases. Increasing temperature can improve the chemical reaction rate35. Addition, it is good for geopolymerization reactions, and more gelling chemical products are formed15,31,53. The soil grains can be cemented and three-dimensional soil skeleton structure is formed. Based on it, the unconfined compressive strength of FA-CCR-NaOH geopolymer treated soil is improved with increasing temperature. The schematic diagram of temperature influence mechanism is presented in Fig. 20. However, Zhang et al.54 investigated the influence of curing conditions on mechanical property and microstructure of halloysite-based geopolymers and it indicated that the development of halloysite-based geopolymer strength is more suitable under room temperature and humid conditions. The increase in temperature is detrimental to the development of strength because of reduction of geopolymerization caused by excessively rapid setting, hardening, and fast evaporation54.

Conclusions

This research evaluated the long-term influence of temperature on properties of FA-CCR geopolymer modified marine soft clay. The following conclusions are concluded:

-

1.

The water content has a significant impact on strength of CCR-FA-NaOH geopolymer solidified soil. The strength of sample with 90.2% water content only accounts for 13.5% of strength with 41% water content. After the curing period exceeds 180 days, the rate of strength increase becomes insignificant. Increasing temperature has the most significant impact on the development of 7-day strength and the strength improvement indexes of temperature effect under all water contents are all equal to or greater than 2.5.

-

2.

Based on the hyperbolic model and modification, the final strength calculation model containing long-term influence of temperature and wc/C was established in this research. The precision verification of strength development model is carried out and the deviation between measured strength and calculated strength was generally within 10%. It indicates that the strength development model proposed in this research is suitable for quantitatively analyzing the long-term influence of temperature on FA-CCR geopolymer modified marine soft clay.

-

3.

Scanning electron microscope test result indicates that increasing water content can lead to reduction of cementitious product. However, elevated temperature can effectively generate the cluster-like gelling material and the marine soft clay particles can be connected together. A three-dimensional soil skeleton structure is generated and is capable of effectively resisting the adverse effects of external loads.

It is of utmost importance to study the long-term influence of temperature on the strength performance. In this research, by modifying the hyperbolic model, a strength development model of geopolymer modified marine soft clay considering long-term influence of temperature was established. It is of great significance and value for the design of geotechnical structures under the long-term influence of temperature. However, considering the local climatic conditions, only the effects of three temperatures (20, 30, 40 °C) on the mechanical properties were investigated. Further studies examining the impact of higher temperatures on mechanical behaviour of geopolymer-stabilised soils are recommended.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yi, Y. L., Li, C. & Liu, S. Y. Alkali-activated ground-granulated blast furnace slag for stabilization of marine soft clay. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 27, 04014146 (2015).

Huang, Y. H., Zhu, W., Qian, X. D., Zhang, N. & Zhou, X. Z. Change of mechanical behavior between solidified and remolded solidified dredged materials. Eng. Geol. 119, 112–119 (2011).

Impe, W. F. V. Soil Improvement techniques and their evolution. In Animal Science Papers and Reports (Netherlands, 1989).

Kirsch, K. & Kirsch, F. Ground Improvement by Deep Vibratory Methods (Spon, 2010).

Mitchell, J. M. & Jardine, F. M. A Guide to Ground Treatment (Construction Industry Research and Information Association, London, 2002).

Kaniraj, S. R. & Havanagi, V. G. Compressive strength of cement stabilized fly ash soil mixtures. Cem. Concr Res. 29, 673–677 (1999).

Ahmed, A. & El Naggar, M. H. Swelling and geo-environmental properties of bentonite treated with recycled bassanite. Appl. Clay Sci. 121–122, 95–102 (2016).

Changizi, F. & Haddad, A. Effect of nano-SiO2 on the geotechnical properties of cohesive soil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 34, 725–733 (2016).

Güllü, H., Canakci, H. & Al Zangana, I. F. Use of cement based grout with glass powder for deep mixing. Constr. Build. Mater. 137, 12–20 (2017).

Shojamoghadam, S., Rajaee, A. & Abrishami, S. Impact of various additives and their combinations on the consolidation characteristics of clayey soil. Sci. Rep. 14, 31907 (2024).

Ismail, A. I. M. & Belal, Z. L. Use of cement kiln dust on the engineering modification of soil materials. Nile Delta, Egypt. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 34, 463–469 (2016).

Jiang, N. J. et al. Multi-scale laboratory evaluation of the physical, mechanical, and microstructural properties of soft highway subgrade soil stabilized with calcium carbide residue. Can. Geotech. J. 53, 373–383 (2016).

Julphunthong, P. et al. Evaluation of calcium carbide residue and fly Ash as sustainable binders for environmentally friendly loess soil stabilization. Sci. Rep. 14, 671 (2024).

Zhang, L. L. et al. Exploration of sulfamethoxazole removal triggered by copper slag-based geopolymer: Radical versus nonradical contributions. Chem. Eng. J. 496, 154310 (2024).

Phetchuay, C., Horpibulsuk, S., Arulrajah, A., Suksiripattanapong, C. & Udomchai, A. Strength development in soft marine clay stabilized by fly ash and calcium carbide residue based geopolymer. Appl. Clay Sci. 127–128, 134–142 (2016).

Wang, D. X. & Abriak, N. E. Compressibility behavior of Dunkirk structured and reconstituted marine soils. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 33, 419–428 (2015).

Sarkar, M., Maiti, M., Malik, M. A. & Xu, S. L. Waste valorization: Sustainable geopolymer production using recycled glass and fly ash at ambient temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 494, 153144 (2024).

Yu, B. W., Du, Y. J., Jin, F. & Liu, C. Y. Multiscale study of sodium sulfate soaking durability of low plastic clay stabilized by reactive magnesia-activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 28, 04016016 (2016).

Chen, H. & Wang, Q. The behaviour of organic matter in the process of soft soil stabilization using cement. Bullet. Eng. Geol. Environ. 65, 445–448 (2006).

Xing, H. F., Yang, X. M., Xu, C. & Ye, G. B. Strength characteristics and mechanisms of salt-rich soil–cement. Eng. Geol. 103, 33–38 (2009).

Hunter, B. D. Lime-induced heave in sulfate-bearing clay soils. J. Geotech. Eng. 114, 150–167 (1988).

Kazemian, S., Prasad, A., Huat, B. B. K., Mohammad, T. A. & Aziz, F. N. A. A. Stabilization of tropical peat by chemical Grout. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 36, 114–128 (2013).

Phummiphan, I., Horpibulsuk, S., Phoo-ngernkham, T., Arulrajah, A. & Shen, S. L. Marginal lateritic soil stabilized with calcium carbide residue and fly ash geopolymers as a sustainable pavement base material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 29(2), 04016195 (2016).

Horpibulsukn, S., Phetchuay, C., Chinkulkijniwat, C. & Cholaphatsorn, A. Strength development in silty clay stabilized with calcium carbide residue and fly ash. Soils Found. 53, 477–486 (2013).

Zhu, J. F., Xia, Y. N., Ju, L. Y., Zheng, Q. Q. & Yang, H. Experimental study on the stabilization of marine soft clay as subgrade filler using binary blending of calcium carbide residue and fly ash. Appl. Ocean. Res. 153, 104230 (2024).

Siddiqua, S. & Barreto, P. N. M. Chemical stabilization of rammed earth using calcium carbide residue and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 169, 364–371 (2018).

Wang, Q., Zhang, R. B., Xu, H. R., Li, M. & Fang, Z. H. Study on mechanical properties and microstructure of fly-ash-based geopolymer for solidifying waste mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134176 (2023).

Horpibulsuk, S., Liu, M. D., Liyanapathirana, D. S. & Suebsuk, J. Behavior of cemented clay simulated via the theoretical framework of the structured cam clay model. Comput. Geotechn. 37, 1–9 (2010).

Zhang, R. J., Zheng, J. J., Cheng, Y. S. & Dong, R. Experimental investigation on effect of curing temperature on strength development of cement stabilized clay. Rock. Soil. Mech. 37, 3463–3471 (2016).

Wang, D. X., Gao, X. Y., Wang, R. H., Larsson, S. & Benzerzour, M. Elevated curing temperature-associated strength and mechanisms of reactive MgO-activated industrial by-products clay-plant Ash geopolymers. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 38, 659–671 (2020).

Al-Mukhtar, M., Lasledj, A. & Alcover, J. Behaviour and mineralogy changes in lime-treated expansive soil at 50 °C. Appl. Clay Sci. 50, 199–203 (2010).

Bao, W. X., Wang, H. B., Lai, H. P. & Chen, R. Experimental study on strength characteristics and internal mineral changes of lime-stabilized loess under high-temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 351, 128945 (2022).

Bi, J. R. & Chian, S. C. Modelling strength development of cement–stabilised clay and clay with sand impurity cured under varying temperatures. Bullet. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 6275–6302 (2021).

Lu, J. G. et al. Shear behavior of cement-stabilized silty clay exposed to low-temperature curing. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 223, 104215 (2024).

Bache, B. K. F., Wiersholm, P., Paniagua, P. & Emdal, A. Effect of temperature on the strength of lime–cement stabilized Norwegian clays. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 148, 04021198 (2022).

Yun, J. M., Song, Y. S., Lee, J. H. & Kim, T. H. Strength characteristics of the cement-stabilized surface layer in dredged and reclaimed marine clay. Korea Mar. Georesour Geotechnol. 24, 29–45 (2006).

Cai, H., Chen, C. F., Wei, S. Q. & Zhu, S. M. Strength development of cemented soil cured in water–air conditions at varied temperatures: Experimental investigation and model characterization. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35, 04022466 (2023).

Zhang, R. J., Lu, Y. T., Tan, T. S., Phoon, K. K. & Santoso, A. M. Long-term effect of curing temperature on the strength behavior of cement-stabilized clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 140, 04014045 (2014).

Salimi, M. & Ghorbani, A. Mechanical and compressibility characteristics of a soft clay stabilized by slag-based mixtures and geopolymers. Appl. Clay Sci. 184, 105390 (2020).

Liu, F. Y., Luo, H. R. & Wan, X. S. Experimental study of the mechanical and thermal properties of Metakaolin based geopolymer stabilized soil during low temperature curing. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 218, 104085 (2024).

Mohammadinia, A., Arulrajah, A., Horpibulsuk, S. & Chinkulkijniwat, A. Effect of fly Ash on properties of crushed brick and reclaimed asphaltin pavement base/subbase applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 321, 547–556 (2017).

Bilondi, M. P., Toufigh, M. M. & Toufigh, V. Experimental investigation of using a recycled glass powder-based geopolymer to improve the mechanical behavior of clay soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 170, 302–313 (2018).

Sabrin, S., Siddiqua, S. & Muhammad, N. Understanding the effect of heat treatment on subgrade soil stabilized with bentonite and magnesium alkalinization. Transp. Geotech. 21, 100287 (2019).

Wang, F. et al. GMCs stabilized/solidified Pb/Zn contaminated soil under different curing temperature: Leachability and durability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 26, 26963–26971 (2019).

Chitambira, B. Accelerated Ageing of Cement Stabilised/Solidified Contaminated Soils with Elevated Temperatures. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (2004).

ASTM D4318-10. Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils (West Conshohocken, PA).

ASTM D2487-10. Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System) (West Conshohocken, PA).

Du, C. X., Yang, G., Zhang, T. T. & Yang, Q. Multiscale study of the influence of promoters on low-plasticity clay stabilized with cement-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 213, 537–548 (2019).

Du, C. X. & Yang, Q. Freeze-thaw behavior of calcium carbide residue-plant Ash stabilized marine soft clay. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 193, 103432 (2022).

Ran, A., Kong, L. W. & Zhang, X. W. Mechanical properties and generalized Duncan–Chang model for granite residual soils using borehole shear tests. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 42, 1723–1732 (2020).

Yuan, B. X. et al. Optimized reinforcement of granite residual soil using a cement and alkaline solution: A coupling effect. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. 17, 509–523 (2025).

Yuan, B. X. et al. Eco-efficient recycling of engineering muck for manufacturing lowcarbon geopolymers assessed through LCA: Exploring the impact of synthesis conditions on performance. Acta Geotech. (2024).

Yuan, B. X. et al. Sustainable utilization of clay minerals-rich engineering muck via alkali activation: optimization of pore structure by thermal treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 258, 107491 (2024).

Zhang, B. F. et al. Effect of curing conditions on the microstructure and mechanical performance of geopolymers derived from nanosized tubular Halloysite. Constr. Build. Mater. 268, 121186 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202203021222033, 202403021212157), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20241585, Xianyang Engineer and Scientist Funding (S2024-CXNL-KJRCTD-DWJS-2707), Scientific and Technology Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (2024L192).

Funding

Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province, (202203021222033, 202403021212157), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20241585, (GZC20241585), Xianyang Engineer and Scientist Funding, (S2024-CXNL-KJRCTD-DWJS-2707), Scientific and Technology Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi, (2024L192).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. S.C.X.: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. W.Y.L.: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. X.Z.J.: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, C., Suo, C., Wang, Y. et al. Long-term influence and calculation model of temperature on strength of marine soft clay solidified with calcium carbide residue-fly ash geopolymer. Sci Rep 15, 45783 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28534-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28534-0