Abstract

In marine environments, strong nonlinear internal solitary waves (ISWs) frequently occur. Due to their significant energy, ISWs have a substantial impact on the deep submergence rescue vehicle (DSRV). This study uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods to establish a numerical model for the stable propagation of ISWs and their interaction with a fixed DSRV, aiming to clarify the effects on the DSRV. Changes in depth lead to transitions in the flow field experienced by the structure. Initially, the flow is dominated by the upper fluid layer, then by both the upper and lower layers, and finally by the lower layer. Consequently, the load characteristics of the structure are complex and variable. Additionally, the drag and lift forces on the DSRV change significantly as it moves through ISWs. Changes in yaw angle result in an exponential increase in drag, according to the sine of the yaw angle. They also cause varying degrees of lift attenuation, complicating the maneuverability of the DSRV when encountering ISWs. Therefore, the effects of depth and yaw angle on the DSRV’s performance should not be overlooked when encountering ISWs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In real marine environments, variations in sunlight, temperature, and salinity lead to stable density stratification in seawater1,2. Under these stratified conditions, internal solitary waves frequently occur3,4, characterized by large amplitudes, long wavelengths, and wide distribution5. During the propagation of internal solitary waves, intense shear flow fields, along with significant amounts of energy and momentum6, often accompany them, leading to substantial instantaneous loads on encountered structures7,8. Extensive research has focused on the interaction between internal solitary waves and various structures, such as cylinders9, slender bodies10, and complex marine structures11, offering preliminary insights into the load characteristics experienced by these structures. Deep submarine rescue vehicle (DSRV), which frequently enters and exits the water during rescue operations, exhibits more complex structural features and operational modes. Considering the significant influence of nonlinear waves on structures12, the load characteristics of such equipment under the influence of internal solitary waves require further investigation.

Cylinders, as the most commonly used structures on marine platforms, experience significant loading effects when encountering internal waves, which directly impact the safety and stability of marine equipment. Numerous studies have focused on the interaction between internal solitary waves and cylindrical bodies, providing in-depth investigations into load characteristics. Ermanyuk and Gavrilov13 conducted experiments on the loading characteristics of a horizontally oriented cylinder encountering internal solitary waves. They found that the horizontal load on the cylinder is small when it is positioned at the interface. Additionally, the thickness ratio between the upper and lower fluid layers influences the horizontal load characteristics when the wave amplitude remains constant. Wang et al.14,15 conducted experiments revealing that the loading variation of a horizontal cylinder encountering internal solitary waves is primarily determined by flow field characteristics, with the load mainly influenced by wave amplitude. They also explained how the evolution of the flow field affects load characteristics. Similar to the horizontal cylinder, the load on a vertical cylinder encountering internal solitary waves is also primarily influenced by wave amplitude9,16. Building on the single-cylinder model, Ding et al17. discovered that a horizontally arranged cylinder with a length-to-diameter ratio of 2.5 experiences the maximum horizontal force. They extended their study to two cylinders and revealed the impact of cylinder diameters and spacing on load characteristics. Wang et al.18 further investigated the effect of a baffle placed at the front of the cylinder on the forces it experiences. In marine engineering, the submerged floating tunnel (SFT) is often considered a cylindrical structure. Zou et al19. studied the load characteristics of SFTs with circular and other cross-sectional shapes, while Chen et al.20, comparing circular and elliptical SFT cross-sections, found that circular sections experience greater horizontal forces. Given the complex influence of internal solitary wave depth on load characteristics, this study focuses on the impact of depth on the load characteristics of DSRV encountering internal solitary waves.

An increasing number of scholars are also focusing on the interaction between internal solitary waves and underwater vehicles. The slender body, as a simplified underwater vehicle structure, has been studied by Wei et al.21, who found that the force on it increases significantly with wave amplitude. Changes in the angle of attack cause a significant increase in horizontal forces, and shift the vertical force characteristics to a " double-peak " form22. The horizontal force on the slender body mainly consists of dynamic pressure and friction, while the vertical force is primarily a combination of wave-induced forces and buoyancy23. Similar to slender bodies encountering internal solitary waves, Liu et al.10 found that the forces on a SUBOFF-submerged body are predominantly influenced by wave amplitude, with the most potent effects occurring near the wave center. Wang et al.24 discovered that the load magnitude in the upper fluid layer is smaller than in the lower fluid layer. Pressure gradients primarily cause the horizontal load on the submerged body, while the vertical load when the vehicle crosses the internal solitary wave is mainly due to gravity. Numerous scholars have studied the interaction between internal solitary waves and structures at various depths, yaw angles, and fluid layer thickness ratios in stratified fluid tanks. As a commonly used underwater structure, the DSRV encounters internal solitary waves during launch and retrieval operations, and its load characteristics under various pitch angles require further investigation. Additionally, the wave direction complicates the forces induced by internal solitary waves, and the impact of yaw angles on the load characteristics of the DSRV needs clarification.

Many scholars, in addition to using experimental and numerical methods, have incorporated the Morrison equation to calculate the structural loads during the interaction between internal solitary waves and simple structures, such as cylinders and slender bodies. Zan et al25. assessed the applicability of the Morrison equation for calculating forces on cylindrical bodies caused by internal solitary waves. They also explored how different methods for determining empirical coefficients affect the solution of vertical cylinder load characteristics under the influence of internal solitary waves26. Wang et al.14 found that horizontal longitudinal and transverse wave forces can be represented using the Morrison equation by projecting velocity in their respective directions. Vertical wave forces can also be calculated based on vertical velocity using the same formula. Cui et al.16 introduced a drag coefficient to calculate the drag characteristics of vertical cylinders subjected to internal solitary waves, resulting in more accurate results. However, the Morrison equation’s application to calculate load characteristics for more complex structures is still limited to simpler bodies, such as cylinders and slender bodies. Therefore, current studies on the interaction between internal solitary waves and complex structures mostly rely on physical model experiments or numerical simulations. Zhen et al.27 investigated the impact of wave amplitude on deep-water artificial seabed (DAS) production systems through experiments. Chen et al.28,29 conducted experiments on the effects of internal solitary waves on semi-submersible platforms. Wang and Zhou30 analyzed the impact of internal solitary waves on tension-leg platforms using numerical methods.

Based on these findings, this study develops a numerical model to investigate the interaction between internal solitary waves and the DSRV. Section 2 presents the fundamental approach used in the numerical model and validates its effectiveness. Section 3 discusses the load characteristics of the DSRV under varying depths, pitch angles, and yaw angles for internal solitary waves with constant amplitude. Finally, Sect. 4 summarizes the main conclusions of the study.

Results

Governing equation

This study simulates the propagation and evolution of internal solitary waves in incompressible stratified fluids and their interaction with DSRV by solving the Navier-Stokes (N-S) equations, including the continuity and momentum equations, using the finite volume method with the Bernoulli approximation. The equations are expressed as follows:

Here, \(\:\rho\:\) denotes fluid density, \(\:t\) represents time, \(\:\varvec{U}\) indicates velocity, \(\:\nu\:\) is the kinematic viscosity, ∇ is the divergence operator, and \(\:p\) denotes pressure, f represents the volume force.

Under the Bernoulli approximation, turbulence calculations simplify to the computation of turbulent viscosity, requiring the introduction of a turbulence viscosity model. This study employs the widely used k-\(\:\epsilon\:\) turbulence model to close the Navier-Stokes equations. The k-\(\:\epsilon\:\) model can improve the accuracy of high-speed flow and vortex flow, and is renowned for its numerical stability, and has been widely applied in studies of internal solitary wave-structure interactions31,32,33. Solving the equations for turbulent kinetic energy (k) and turbulence dissipation rate (\(\:\epsilon\:\)) determines the turbulent viscosity, enabling the resolution of turbulence. The equations for k and \(\:\epsilon\:\) are as follows:

The equation for turbulent viscosity is:

In this equation, \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) represents the dynamic viscosity coefficient, with the empirical constants \(\:{C}_{1\epsilon\:}\) and \(\:{C}_{2\epsilon\:}\:\)typically set to 1.44 and 1.92.

Numerical feasibility

After establishing the numerical method used in this study, we performed calculations based on the experiments by Hu et al.34 The resulting internal solitary waveforms were compared with the experimental waveforms, as shown in Fig. 1. The reliability of the method was further validated by calculating the drag force on the standard Suboff model at various inflow velocities in a uniform flow environment. These results were compared with the experimental data40. Five representative velocities were selected, and the corresponding results from both simulations and experiments are presented in Table 1. The table clearly demonstrates that the numerical method employed in this study accurately predicts the drag forces on the structure. Despite the geometric differences between the Suboff and DSRV models, the total resistance of such underwater bodies is primarily driven by frictional and viscous pressure resistance. The accurate reproduction of Suboff’s total resistance thus validates the effectiveness of the current numerical setup in capturing both surface shear stress and the primary pressure distribution over the body. This confirms the numerical method’s capability to accurately calculate the load characteristics of structures under the internal solitary waves.

Comparison between the numerical waveform and the experimental waveform34.

Fig. 2 illustrates the drag and lift forces obtained from simulations with three different mesh resolutions. Considering that the primary flow field characteristics in the evolution of internal solitary waves are concentrated near the wavefront, the computational domain in the subsequent studies of this paper was divided using a medium-density mesh, as shown in Fig. 3. Additionally, adaptive mesh refinement techniques were applied to capture more precise flow field information near the wavefront.

Numerical setup

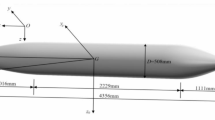

The numerical flume in this study measures 8 m in length, 0.4 m in width, and 0.5 m in height, as shown in Fig. 4. The upper layer of the flume consists of freshwater with a thickness of 0.1 m and a density of 1000 kg/m³, while the lower layer is saltwater, 0.4 m thick, with a density of 1025 kg/m³. Both layers have a dynamic viscosity of 0.0001 m/s². The numerical simulation uses a scaled-down model of the structure with a scaling ratio of 0.025. The entire numerical flume is discretized with a cutting-body grid, and grid refinement is applied in the internal solitary wave region to ensure stable wave propagation. Surface grid refinement and prismatic layer meshing are applied to the DSRV to provide the necessary precision for the k-\(\:\epsilon\:\) turbulence model calculations. In the numerical simulations, the internal solitary wave’s wavefront is captured using the Volume of Fluid (VOF) method.

Method for generating internal solitary waves

In the numerical study of internal solitary wave generation, several wave generation methods have been developed, including the gravitational collapse35, velocity inlet36, and initialization wave generation methods37. The gravitational collapse method uses the gravitational potential energy difference between two fluid layers to generate internal solitary waves. However, this method requires time for wave generation and stabilization, resulting in a longer computational domain and duration, which reduces computational efficiency. The velocity inlet method generates internal solitary waves by setting opposing flow directions for the two fluid layers at the boundary. The initialization wave generation method, based on theories like eKdV, obtains the wave’s two-phase distribution and velocity profile, which is then applied to the initial flow field. Since internal solitary wave propagation is considered a quasi-two-dimensional problem, the two-dimensional wave field is combined using a slicing technique to form a three-dimensional flow field, generating the internal solitary wave. Due to the limitations of the gravity collapse method, most researchers prefer the latter two methods.

This study employs the initialization wave generation method to simulate the propagation and evolution of internal solitary waves. Unlike methods that use theoretical results from eKdV38, mKdV37, or DJL39 to initialize internal solitary waves, this study follows the method used by Yu et al.33. A two-dimensional numerical flume is established using the same method for gravity collapse wave generation, capturing the stabilized flow field data after wave propagation. The phase distribution and velocity characteristics of the stabilized internal solitary wave are transferred to a three-dimensional numerical flume. Multiple two-dimensional flow fields are combined through slicing to initialize the three-dimensional internal solitary wave, as shown in Fig. 5.

Discussion

Extensive research has been conducted on the interaction between internal solitary waves and structures. Many studies have investigated parameters such as the thickness and density ratios of the upper and lower fluid layers, wave amplitude, structure submersion depth, and yaw angle. These studies have shown that the load on the structure increases with larger wave amplitudes. However, changes in parameters such as submersion depth and wave approach angle result in more complex variations in the load on the structure. Therefore, this study focuses on the load characteristics of DSRV under the influence of internal solitary waves, considering various submersion depths(d*), which is defined as the distance from the DSRV’s center of gravity to the interface between the two-phase fluid. The pitch angle (𝜃) is defined as the angle between the DSRV’s longitudinal axis in the mid-transverse plane and the horizontal direction, with a positive value indicating a tilt of the bow towards the positive 𝑧-direction. The yaw angle (𝛽) is defined as the angle between the DSRV’s longitudinal axis in the waterplane and the horizontal direction, with a positive value indicating a tilt of the bow towards the positive 𝑦-direction. The working conditions are summarized in Table 2.

Influence of submersion depth

The forces experienced by a submerged body in the lower fluid layer, when subjected to internal solitary waves, are particularly complex24. Therefore, this study focuses on the submersion depth in the lower fluid layer. As the submersion depth of the DSRV changes, the resulting resistance characteristics (\(\:{F}_{x}^{*}=\frac{{F}_{x}}{{\rho\:}_{1}gSH}\), H represents the overall height of the computational domain in the z-direction.) also vary. As shown in Fig. 6a, at a submersion depth of d* = −0.3, the DSRV is closest to the interface between the two fluid layers, where the resistance variation is most distinct. Specifically, the resistance increases as the internal solitary wave approaches and decreases as the wave moves away. In contrast, at larger submersion depths (d* = −1.2 and − 1.5), the resistance shows the opposite trend. At other submersion depths, the resistance characteristics become more complex. At both low and high submersion depths, the DSRV experiences a prominent single peak in resistance, whereas at intermediate depths, notable fluctuations occur in both positive and negative directions. The lift characteristics (\(\:{F}_{z}^{*}=\frac{{F}_{z}}{{\rho\:}_{1}gSH}\)) follow a similar trend to the resistance. Specifically, at low and high submersion depths, the lift behaves oppositely: it decreases after the internal solitary wave passes at high depths, while it increases at low depths. Moreover, as the submersion depth increases, the amplitude of lift variation decreases.

To investigate the effect of submersion depth on the resistance characteristics of DSRV, three submersion depths (d* = −0.3, −0.9, −1.5) were selected. Fig. 7 shows the velocity field around the DSRV as the internal solitary wave (ISW) passes. At both low and high submersion depths (d* = −0.3), the flow field around the DSRV shows distinct characteristics. At a low submersion depth, the flow field around the DSRV is mainly influenced by the movement of the upper fluid layer. During the internal solitary wave propagation, the DSRV remains within the upper fluid layer, except for a brief interaction with the lower fluid near the DSRV when the wave first encounters it. Consequently, the resistance characteristics are primarily influenced by the motion of the upper fluid layer, as indicated by the positive, unidirectional change in Fig. 6a. As the submersion depth is below the two-phase interface, the lift on the DSRV is initially supported by the buoyancy of the lower fluid. As the internal solitary wave propagates past the DSRV, the surrounding environment shifts from the lower to the upper fluid, and the lift becomes dominated by the buoyancy of the upper fluid. Since the density of the upper fluid is lower, the lift on the equipment decreases further.

At high submersion depths, the environment around the DSRV stays within the lower fluid layer throughout the passage of the internal solitary wave. Therefore, the resistance on the DSRV is consistently influenced by the flow field of the lower fluid layer, leading to a single, opposite directional change in resistance. The lift experienced by the DSRV remains weak throughout the wave propagation, as the buoyancy of the lower fluid primarily influences it. In the early stages of internal solitary wave propagation, the fluid velocity above the DSRV slightly exceeds that below it. This velocity gradient produces a weak downward force on the DSRV, counteracting some of the buoyancy from the lower fluid. Consequently, the lift slightly reduces in the early phase. After the internal solitary wave passes the DSRV, the surrounding fluid flow becomes dominated by the lower fluid, which has a higher velocity. The resulting velocity gradient creates an upward force on the DSRV. Additionally, the attachment of the flow to the rear of the DSRV hinders fluid movement above it, significantly reducing its speed and generating a greater upward force. This phenomenon is reflected in the increased lift experienced by the DSRV in the later stages of internal solitary wave propagation, as shown in Fig. 6b.

The resistance and lift experienced by the DSRV are primarily influenced by the fluid layers of the internal solitary wave (ISW) above and below it. When the DSRV is entirely within the upper or lower fluid layers, the resulting changes are distinctly opposite, but their characteristics are similar. At intermediate submersion depths, the load characteristics become more complex, with changes occurring in both positive and negative directions. Fig. 7h - n shows the velocity field when the DSRV is at d* = −0.9. As the internal solitary wave propagates, the DSRV crosses the wavefront, moving from the lower fluid to a combined environment of both fluid layers. As the internal solitary wave continues propagating, the environment shifts back to the lower fluid. As a result, the resistance and lift experienced by the DSRV follow the patterns shown in Fig. 6. In the early stages of internal solitary wave propagation, the flow field around the DSRV is similar to that at high submersion depths, dominated by the movement of the lower fluid. As a result, the resistance changes are consistent with those observed at high submersion depths.

Due to the higher velocity of the fluid above the DSRV, some lift is counteracted, resulting in a slight reduction. As the internal solitary wave propagates, the flow field around the DSRV becomes influenced by both fluid layers, with the upper fluid gradually dominating. The resistance changes from negative to positive, and the lift decreases as buoyancy from the upper fluid diminishes. As the submersion depth increases, the influence of the upper fluid on the DSRV diminishes, as shown in Fig. 6b. The magnitude and duration of the reduction in lift decrease. As the internal solitary wave propagates, the surrounding fluid shifts back to the lower layer, and the resistance begins to decrease and gradually recover, while the lift continues recovering. During this process, the lift change is significantly larger than that in resistance, with the pitching moment on the DSRV primarily driven by lift. Therefore, the lift change is strongly correlated with the height of the DSRV. The load variation characteristics observed when the DSRV encounters the internal solitary wave at different submersion depths show that the resistance is mainly driven by the velocity induced by the internal solitary wave. Thus, the internal solitary wave is the primary factor responsible for the changes in resistance. The lift characteristics are mainly governed by the background flow, with lift changes due to the velocity gradient of the internal solitary wave being weaker than those caused by the background flow.

Influence of pitch angle

The previous section demonstrated that the load characteristics of DSRV at intermediate depths are complex. This section investigates the effect of \(\:\theta\:\) changes on the load characteristics of the DSRV at a depth of d* = −0.6.

Fig. 8 shows that the \(\:\theta\:\) of the DSRV changes from a downward to an upward dive. During this process, the resistance varies through four turning points, with a more intricate change. The resistance first increases in the reverse direction, then reaches a reversed value over a specific time frame at different θ. The resistance then decreases before increasing again to a new positive value. The resistance continues to decline, reaching a minimum, then increases again and stabilizes. The variation in lift is simpler. As the θ increases, the magnitude of lift decay decreases. Specifically, when encountering internal solitary waves, the significant θ characteristics of the DSRV mitigate the influence of the flow field on lift.

As shown in Fig. 8a, the resistance characteristics of the DSRV are pretty complex. After reaching the maximum positive value, the resistance does not immediately return to its original state but continues to increase, showing a secondary increase in resistance. This characteristic is used to identify the turning point in the resistance change and the corresponding velocity field before and after the process, as shown in Fig. 9a. Subsequently, DSRV passes through the internal solitary wave, as shown in Fig. 9b and Fig. 9c. Before the first trough point, the flow field around the DSRV is mainly within the lower fluid layer, causing the resistance to increase. After the trough point, the DSRV enters the upper fluid layer of the internal solitary wave, with resistance continuously growing in the positive direction, as shown in Fig. 9d and Fig. 9e. At this point, the DSRV is close to the wave trough, and the maximum velocity difference between the upper and lower fluids acts on it, resulting in the maximum resistance. After reaching the maximum resistance, the DSRV moves further from the internal solitary wave, while the surrounding fluid velocity difference does not decrease significantly. When Fig. 9f is reached, the resistance decreases to the second trough point. In Fig. 9g, as the internal solitary wave propagates, the impact of the lower fluid velocity on the DSRV weakens rapidly, causing the velocity difference around it to increase, resulting in a second positive velocity peak, as shown in Fig. 9h. Following this, the internal solitary wave moves further from the DSRV, as shown in Fig. 9i, and the flow field around it continues to weaken, causing the resistance to decrease. Simultaneously, the pitching moment changes similarly to the lift. The buoyant force from the fluid primarily influences the variation in lift. The velocity gradient difference between the upper and lower parts of the DSRV has a slight effect on the DSRV’s performance. As the pitching angle changes, the resistance does not decrease significantly. For larger angles, it decays more slowly, indicating that the influence of the internal solitary wave on the DSRV weakens.

Influence of Yaw angle

During the actual operation of DSRV, various navigation angles are encountered. This section examines the load characteristics of the DSRV when it encounters internal solitary waves at different navigation angles by varying the angle between the DSRV’s extension length and the wave propagation direction.

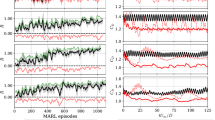

In the following discussion, the amplitude and propagation direction of the internal solitary wave, as well as the centroid position of the DSRV, remain unchanged. Only the navigation angle of the DSRV is changed, covering seven operational conditions where the DSRV faces or encounters the internal solitary wave from behind. The impact of β changes on the load characteristics can be divided into two stages. Stage Ⅰ occurs when the β increases from 0° to 90°, during which the resistance experienced by the DSRV increases continuously in a nearly linear pattern. Stage Ⅱ occurs as the β increases from 90° to 180°, where the resistance decreases in a near-linear trend. These two stages can be summarized by the fact that when the minimum angle between the β and the wave propagation direction is the same, the resistance change characteristics are highly similar. Specifically, at 45° and 135°, the minimum angle between the DSRV’s extension length and the wave propagation direction is 45°, leading to nearly identical resistance change characteristics in both cases, as shown in Fig. 10a. This is also observed when the β is 0° and 180°. Since the flow field around the DSRV is a constant-amplitude internal solitary wave field, changes in the β alter the DSRV’s wave-facing area20. In Stage Ⅰ, the larger the β, the greater the wave-facing area, leading to an increased resistance.

Fig. 10d shows the relationship between the resistance magnitude and the sine of the β. The resistance magnitude and the sine of the β follow a similar inverse sine function relationship. Therefore, when the amplitude of the internal solitary wave is constant, the wave-facing area of the DSRV significantly impacts the resistance it experiences. Changes in the β result in similar lift and resistance characteristics when the minimum angle is constant. Both follow identical trends. In contrast to θ changes, β changes have a negligible effect on lift. As shown in Fig. 10b, the magnitude of lift decay remains nearly constant. Compared to lift changes under θ adjustments, the lift experienced by the DSRV when encountering internal solitary waves behaves differently before reaching the decay magnitude due to β changes. There is a distinct difference between the change of My and the change of resistance, as shown in Fig. 10c. When β = 45o, My has a maximum value. On both sides of 45o, the maximum value decreases continuously, and the influence of small angle on My is weak. There was no significant change in the amplitude as a whole.

In Stage Ⅰ, as the β increases, the DSRV reaches the decay magnitude of lift at nearly the same time. However, the lift evolution under different β, highlighted by the red dashed box in Fig. 10b, exhibits varying characteristics. At small β, the lift rapidly decays before slowing, while at medium β, the decay is more uniform. As the β continues to increase, the lift first decays slightly before rapidly decreasing, particularly at 90°, where a smooth transition region is observed. The influence of depth on the lift characteristics of the DSRV is mainly due to the background flow field. When the β changes, the DSRV’s wave-facing area increases due to the angle deviation. During the propagation of internal solitary waves, the DSRV’s volume in the upper fluid layer increases. As a result, the buoyancy from the lower fluid decreases more rapidly. As shown in the red dashed box in Fig. 10b, the lift decays more quickly as the β increases. Additionally, the angle change causes the DSRV to encounter the wave trough of the internal solitary wave later, leading to a slower variation of lift in the first half of the box. Considering that the pitch moment of the DSRV is referenced to the y-axis of the global coordinate system and is mainly dominated by lift, the pitch moment decreases in magnitude as the β increases in the initial phase. However, during the propagation of internal solitary waves, the changes in pitch moment and its magnitude align with the lift characteristics. This indicates that the pitch moment experienced by the DSRV is mainly dominated by the lift generated by the background flow field.

Conclusion

Based on CFD methods, this study investigates the interaction between a deep sub-mergence rescue vehicle (DSRV) and an internal solitary wave (ISW) with varying wave amplitudes under different operating conditions, including submersion depth, β, and θ. By establishing the correlation between the flow field around the DSRV during ISW evolution and the resulting hydrodynamic load characteristics, this work elucidates the load behavior acting on the DSRV under ISW excitation.

When DSRV encounters internal solitary waves, its resistance is mainly influenced by the velocity field caused by wave propagation, while lift is primarily governed by the upward buoyancy from the background flow field. This finding is consistent with previous studies.

Depth significantly affects the load experienced by the DSRV during the propagation of internal solitary waves. Varying depth changes the flow field environment encountered by the DSRV, resulting in different resistance characteristics. Moreover, when the DSRV traverses internal solitary waves, its resistance becomes more complex. As the background flow field mainly governs the lift, depth primarily affects the ratio of the DSRV’s position in the upper and lower fluid layers. When the DSRV is entirely in the lower fluid layer, its lift remains almost unchanged. However, when the DSRV moves through the internal solitary waves, its lift rapidly decays, and the amplitude of its attenuation approximately doubles.

Changes in θ make the resistance experienced by the DSRV more complex. As θ increases, the resistance magnitude decreases. Notably, the resistance amplitude at θ = 180 ° is approximately 4 times that at θ = 0°. However, the resistance at locations farther from the internal solitary wave becomes more pronounced. Increasing the θ reduces both the duration and magnitude of lift decay, but the overall effect is relatively weak.

As the β increases, the DSRV’s wave-facing area expands, leading to a rise in resistance, with the rate of increase following an exponential trend. Although changes in β minimally affect the magnitude of lift decay, they introduce more complex changes in lift characteristics, making maneuvering more difficult when encountering internal solitary waves. Consequently, the DSRV should alter its β when facing an internal solitary wave. By doing so, it minimizes its presented area to the oncoming wave, thus reducing the wave’s adverse effects on works.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, M. et al. Study on the mechanical characteristics and failure mechanism of the coastal Bridge with a box-girder superstructure under the action of breaking solitary waves. Ocean. Eng. 287, 115834 (2023).

Zou, L., Zhao, T., Ma, X., Wang, X. & Gao, Y. Numerical study of submerged body tail linearization in a strongly stratified fluid on the characteristics of generated internal waves. Ocean. Eng. 288, 116024 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Non-Boussinesq effect on the internal solitary wave propagation under a Lagrangian-like description for various Pycnocline thickness conditions. Phys. Nonlinear Phenom. 458, 134007 (2024).

Zou, L., Gao, Y., Sun, T., Ma, X. & Yu, Z. Experimental investigation of propagation evolution characteristics of internal solitary waves passing through downslope topography. Phys. Fluids. 36 (3), 033611 (2024).

Zou, L., Wen, Z., Sun, T., Ma, X. & Wang, X. Experimental study on transformation and energy properties of depression internal solitary wave over a bottom step. Phys. Fluids. 33 (3), 032109 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Spectral analysis of internal solitary waves propagating over a stepped bottom topography via the Koopman operator. AIP Adv. 11(4), 045225 (2021).

Sveen, J. K., Guo, Y., Davies, P. A. & Grue, J. On the breaking of internal solitary waves at a ridge. J. Fluid Mech. 469, 161–188 (2002).

Sutherland, B. R., Keating, S. & Shrivastava, I. Transmission and reflection of internal solitary waves incident upon a triangular barrier. J. Fluid Mech. 775, 304–327 (2015).

Chen, X. et al. A study of the interaction between depression internal solitary waves and submerged floating tunnels in stratified fluids. Appl. Ocean. Res. 132, 103455 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Multi-Parameter influence analysis of interaction between internal solitary wave and fixed submerged body. China Ocean. Eng. 37 (6), 934–947 (2023).

Zou, L., Ma, X., Hu, Y., Wang, X. & Gao, Y. Experimental study on interaction between the internal solitary wave and a hydrofoil based on the spectral proper orthogonal decomposition. Phys. Fluids. 35 (11), 112118 (2023).

Haider, R. et al. Dynamic response of floating offshore wind turbine to focused wave excitation. Phys. Fluids. 37 (8), 082120 (2025).

Ermanyuk, E. V. & Gavrilov, N. V. Experimental study of the dynamic effect of an internal solitary wave on a submerged circular cylinder. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 46(6), 800–806 (2005).

Wang, S. D. et al. Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional oblique interaction of an internal solitary wave with a horizontal finite-length cylinder. J. Fluids Struct. 111, 103553 (2022).

Wang, S., Du, H., Wei, G., Peng, P. & Xuan, P. Experimental modification of the internal solitary wave force exerted on a horizontal transverse cylinder due to wave-flow and vortex shedding. Ocean. Eng. 269, 113513 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. An improved method for estimating internal solitary waves force on small circular cylindrical structures. Mar. Struct. 87, 103329 (2023).

Ding, W., Sun, H., Zhao, X. & Ai, C. Numerical investigation of an internal solitary wave interaction with tandem horizontal cylinders. Ocean. Eng. 246, 110658 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Reduction of internal-solitary-wave-induced forces on a circular cylinder with a splitter plate. J. Fluids Struct. 83, 119–132 (2018).

Zou, P. X., Bricker, J. D. & Uijttewaal, W. S. J. The impacts of internal solitary waves on a submerged floating tunnel. Ocean. Eng. 238, 109762 (2021).

Chen, X., Liang, J. H., Xu, G. & Chen, Q. A study on the interaction between circular or elliptical cross-section submerged floating tunnels and elevation internal solitary waves. Ocean. Eng. 285, 115291 (2023).

Wei, G. et al. Experimental investigation of the generation of large-amplitude internal solitary wave and its interaction with a submerged slender body. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 57 (2), 301–310 (2014).

Wang, S. D. et al. Experimental investigation of the wave-flow structure of an oblique internal solitary wave and its force exerted on a slender body. Ocean. Eng. 201, 107057 (2020).

Xuan, P., Du, H., Wang, S. D., Peng, P. & Wei, G. Experimental and theoretical study of internal solitary wave loads on a submerged slender body. Ocean. Eng. 272, 113936 (2023).

Wang, R., Zhi, C. & You, Y. Numerical study of internal solitary wave loads on a submerged slender body with multi-parameter coupling. Phys. Fluids 36(11), 113361 (2024).

Zan, X. & Lin, Z. On the applicability of Morison equation to force Estimation induced by internal solitary wave on circular cylinder. Ocean. Eng. 198, 106966 (2020).

Zan, X., Lin, Z. & Gou, Y. Numerical study on the force distribution on cylindrical structure by internal solitary wave and its prediction with Morison equation. Ocean. Eng. 248, 110701 (2022).

Zhen, X., Lv, Y., Duan, Q. & Huang, C. Experimental investigation on the nonlinear dynamic responses of the coupled floating submerged artificial seabed-mooring system in internal solitary waves. Ocean. Eng. 288, 116092 (2023).

Chen, M., Chen, K. & You, Y. X. Experimental investigation of internal solitary wave forces on a semi-submersible. Ocean. Eng. 141, 205–214 (2017).

Chen, M., Chen, J. & You, Y. X. Forces on a semi-submersible in internal solitary waves with different propagation directions. Ocean. Eng. 217, 107864 (2020).

Wang, X. & Zhou, J. Numerical and experimental study of internal solitary wave loads on tension leg platforms. J. Hydrodyn 33(1), 93–103 (2021).

Ding, W., Sun, H., Zhao, X. & Ai, C. Numerical study of the interaction between an internal solitary wave and a submerged extended cylinder using openfoam. Ocean. Eng. 274, 113985 (2023).

Wang, J., Chang, Q., He, Z. & Wu, W. Numerical investigation on motion responses of high-speed self-propelled submersible subject to internal solitary wave. Phys. Fluids 36(12), 123106 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Numerical investigation on motion response and load characteristics of interaction between internal solitary wave and multi-unmanned underwater vehicles. Ocean. Eng. 320, 120156 (2025).

Hu, Y., Ma, X., Zou, L., Yu, Z. & Zhao, J. Numerical investigation of the propagation of internal solitary waves and their reflection by a vertical wall based on a fully nonlinear model. Ocean. Eng. 314, 119776 (2024).

Zhang, J., Jin, G., Cai, Z., Zheng, K. & Zou, L. Numerical investigation on the amplitude and mechanics of internal solitary waves generated by the gravity collapse method. Appl. Ocean. Res. 150, 104127 (2024).

Wang, J., He, Z., Xie, B., Zhuang, C. & Wu, W. Numerical investigation on the interaction between internal solitary wave and self-propelled submersible. Phys. Fluids. 35 (10), 107119 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Dynamics and ‘falling deep’ mechanism of submerged floating body under internal solitary waves. Ocean. Eng. 288, 116058 (2023).

Li, J., Zhang, Q. & Chen, T. ISWFoam: a numerical model for internal solitary wave simulation in continuously stratified fluids. Geosci. Model. Dev. 15 (1), 105–127 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. Numerical investigation on the interaction between large-scale continuously stratified internal solitary wave and moving submersible. Appl. Ocean. Res. 145, 103938 (2024).

Funding

This project was supported by the Program of Deep Submarine Rescue Vehicle Training Simulation System (No. 2021-HCX-MN-020006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z. and C.L.; software, H.Z., C.L. and X.W.; validation, D.L., J.G. and X.P.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, D.L. and X.D.; resources, J.G.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z and C.L.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., C.L. and D.L.; visualization, J.G.; funding acquisition, H.Y.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, H., Liu, C., Wei, X. et al. Numerical study on the load characteristics of deep submarine rescue vehicle under the internal solitary waves. Sci Rep 15, 45780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28561-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28561-x