Abstract

This study aims to investigate the chain mediating effect of consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity on the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior. A survey was conducted with 4813 adolescents using the School Physical Activity Scale, the Consolidated Helicopter Parenting Scale, the Brief Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and the PROCESS macro for correlation analysis, regression analysis, and chain mediation effect testing. (1) Physical activity is positively correlated with adolescent aggressive behavior and can positively predict consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and aggressive behavior. (2) Consolidated helicopter parenting positively predicts adolescent impulsivity and aggressive behavior, while adolescent impulsivity positively predicts aggressive behavior. (3) A significant chain mediation effect was found, where physical activity indirectly influences aggressive behavior through the path consolidated helicopter parenting → adolescent impulsivity. Physical activity can exacerbate adolescent aggressive behavior by enhancing the level of consolidated helicopter parenting and increasing adolescent impulsivity. This chain mediation mechanism provides new insights into the causes of adolescent aggressive behavior and offers practical implications for school sports interventions and family educational guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aggressive behavior refers to the psychological and behavioral tendency of individuals to intentionally harm others, either directly or indirectly, resulting in negative physical and mental impacts on the victim1,2. It is prevalent among adolescents and is characterized by a tendency toward younger ages and higher frequencies. School environment is one of the key factors influencing adolescent aggressive behavior3. A survey by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) revealed that one in three students aged 9 to 15 has engaged in physical conflict with peers, and 32.4% of students have experienced physical aggression within the past 12 months4. In extreme cases, juvenile impulsive aggression can lead to serious criminal incidents that not only severely disrupt social order but also cause indelible trauma to the victim’s family. Therefore, investigating the influencing factors and mechanisms of aggressive behavior, including family upbringing patterns and individual psychological traits, is crucial for understanding its development and formulating effective intervention strategies. This research holds significant theoretical and practical value in fostering a harmonious and stable school and social environment.

Although previous studies have examined the independent effects of physical activity, family upbringing, and individual traits on adolescent aggressive behavior, the interaction between these factors and their chain-like transmission mechanisms remain key research gaps, providing clear academic positioning and innovation space for the present study. The theoretical perspective on the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior is currently marked by significant controversy. Some studies suggest that physical activity, especially non-competitive exercise, can suppress aggressive behavior by releasing negative emotions and cultivating rule consciousness5,6. In contrast, other studies find that high-intensity, competitive physical activity may activate aggressive behavior cues and exacerbate aggressive tendencies7,8. The core reason for this contradiction lies in the fact that existing research predominantly focuses on the direct relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior, or tests a single mediating variable, neglecting the chain-like transmission mechanism of the environment-family-individual interaction9,10.There is a notable gap in research regarding the chain-mediated effects of consolidated helicopter parenting (family system) and adolescent impulsivity (individual traits)—a crucial link bridging physical activity contexts and aggressive behavior. Accordingly, this study employs the General Aggression Model (GAM) as the core framework, integrating family systems theory to deconstruct the mechanisms of aggressive behavior into a three-dimensional process involving situational input, internal states, and social interactions. Specifically, external environmental cues trigger neuropsychological responses in cognitive, emotional, and physiological systems, which then create a positive feedback loop in social interactions, ultimately leading to the automatic processing of cognitive scripts and the manifestation of overt aggressive behavior.

Research hypothesis

Physical activity and aggressive behavior

Physical activity, as an active lifestyle, has long been a focal point of academic attention regarding its impact on individuals’ psychological and behavioral outcomes. Existing research suggests a potential link between physical activity and aggressive behavior, although conclusions regarding their relationship are inconsistent. Some studies indicate that physical activity may reduce aggressive behavior11, while others propose it could exacerbate aggression12, and some suggest no significant correlation between the two13. The significant heterogeneity among these findings suggests that the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior may involve nonlinear and multidimensional pathways, necessitating further theoretical modeling and empirical research to explore potential mediating variables and underlying mechanisms. Bushman’s14 research found that athletes participating in high-intensity competitive sports exhibited significantly higher verbal aggression scores in laboratory settings compared to non-athletes, potentially due to the generalization of contextual cues related to legitimate aggression in sports. Moreover, physiological arousal induced by physical activity, if not adequately managed, may serve as a physiological foundation for aggressive behavior15. Although some studies suggest that aerobic exercise may reduce aggressive behavior, multiple empirical studies indicate a significant correlation between high-intensity competitive sports and adolescent aggression. Eime et al.16 highlighted that adolescents participating in high-intensity competitive sports exhibited a significant increase in the frequency of adolescent impulsivity in the short term. A longitudinal study by Reynes et al.17 confirmed that adolescents continuously engaged in judo exhibited higher levels of aggressive behavior, particularly in verbal aggression and anger. This phenomenon may stem from the goal-oriented nature of competitive sports, where an emphasis on winning at all costs weakens moral inhibitions against aggressive behavior, and repeated physical contact may reduce sensitivity to aggression18. When the intensity or duration of physical activity exceeds an individual’s adaptive threshold, overtraining may trigger negative emotions such as anxiety and irritability, subsequently increasing the likelihood of aggressive behavior. Selmi et al.19 pointed out that sustained high-intensity training disrupts the physiological and psychological balance of individuals, leading to a significant increase in negative emotions such as anxiety and irritability. A longitudinal study by Endresen et al.20 found that adolescents engaged in strength training exhibited an increase in antisocial behavior, both violent and non-violent, beyond the context of sports. This suggests that the positive correlation between physical activity and aggressive behavior may follow a dose-dependent effect. Based on this, the present study proposes Hypothesis 1: Physical exercise (primarily referring to high-intensity, confrontation-related exercise, such as high-intensity resistance training and contact competitive sports) is positively correlated with aggressive behavior in adolescents.

The mediating role of consolidated helicopter parenting

Consolidated helicopter parenting typically refers to parents exercising a high level of control over their children’s lives and behaviors, similar to a helicopter hovering above, constantly ready to intervene or make decisions on their behalf21. The intensity, type, and potential risks of physical activity may serve as trigger cues for parents to adopt overprotective behaviors. From the perspective of family systems theory22, parents’ concerns about injuries and interpersonal conflicts significantly increase when adolescents engage in high-intensity competitive sports. This, in turn, enhances their intervention behaviors through the threat-assessment mechanisms outlined in Protection Motivation Theory. Studies have shown that the frequency of children’s participation in physical activity is positively correlated with the Consolidated Helicopter Parenting score23. Adolescents involved in competitive sports experience higher rates of excessive communication and behavior substitution by their parents compared to those from typical households. This reinforcement of parenting behavior may stem from parents’ cognitive bias regarding the dangerousness of the sports environment. Even when objective risks are low, parents often resort to controlling behaviors to alleviate their own anxiety24,25. Overcontrol by parents disrupts the balance between moderate monitoring and autonomous development, preventing adolescents from fulfilling their need for autonomous decision-making in sports settings, which leads to resistance through aggressive behavior26,27. Furthermore, Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, by resolving conflicts on behalf of children, deprives adolescents of opportunities to practice emotional regulation in sports. Adolescents subjected to prolonged overprotection show a greater increase in cortisol levels when confronted with unfair judgments in sports and are more prone to exhibit aggressive behaviors, such as pushing and verbal abuse28,29. Based on these observations, Hypothesis 2 is proposed: Consolidated Helicopter Parenting mediates the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior. Physical activity strengthens Consolidated Helicopter Parenting by activating parents’ protective anxiety. This overcontrol, in turn, increases the risk of aggression through the deprivation of autonomy and emotional regulation deficits, forming a complete mediation pathway.

The mediating role of adolescent impulsivity

Adolescent impulsivity can be categorized into cognitive impulsivity and behavioral impulsivity, both of which reflect a tendency to act without foresight or regard for consequences30,31. High-intensity competitive sports enhance impulsivity effects, as the instant reaction prioritized over rational assessment logic in sports such as football and boxing alters neural pathways—reducing the connectivity efficiency between the prefrontal cortex (responsible for inhibitory control) and motor cortex, thereby increasing impulsivity scores in adolescents32,33,34. Adolescents who frequently engage in competitive sports tend to be more impulsive, which may be linked to the generalization of the cognitive pattern in sports where the goal of winning suppresses risk assessment35,36. In contrast, low-intensity aerobic exercises, such as jogging and yoga, may mitigate adolescent impulsivity37. However, this hypothesis focuses on the mediation pathway of high-intensity sports, as it has a more significant association with adolescent aggressive behavior. Moreover, the combination of impulsivity related to sports and unplanned impulsivity weakens the prefrontal cortex’s inhibitory control over aggressive behavior, increasing the likelihood of physical aggression in adolescent school conflicts, with the sport-related impulsivity dimension being the strongest predictor38,39. Individuals with high cognitive impulsivity scores are more likely to attribute hostile intentions to ambiguous situations than those with lower scores (e.g., interpreting an unintentional collision with a classmate as deliberate provocation)40,41. Based on this, Hypothesis 3 is proposed: Adolescent impulsivity mediates the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior.

The chain-mediating roles of consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity

The General Aggression Model (GAM) posits that aggressive behavior results from the dynamic coupling of external contexts, individual traits, and social interaction systems15. The model suggests that situational input (e.g., high-intensity confrontational activities) activates cognitive and emotional systems, which, through the process of social interactions, ultimately lead to aggressive behavior. In this study, the core mechanism of this process is further clarified by incorporating family systems theory, specifically the Consolidated Helicopter Parenting model within family interactions. Family systems theory offers a micro-level explanation of the social interaction process within the General Aggression Model (GAM). As the primary social system influencing individuals, family dynamics, including parenting practices such as overprotection and control, significantly impact how situational inputs are transformed into individual traits. This framework underpins the integration of both theories in this study. The confrontational nature of physical activity activates and strengthens parents’ Consolidated Helicopter Parenting behaviors through two key mechanisms. First, from the perspective of GAM’s situational input risk perception, confrontational sports inherently involve injury risks (e.g., joint injuries from basketball collisions or muscle strains in football). As protectors within the family system, parents often overestimate these risks, triggering overprotective behaviors9,42. Second, from the emotional arousal driven by achievement, confrontational sports are frequently linked to adolescents’ external achievement evaluations, leading parents to heighten controlling behaviors due to achievement-related anxiety. This dual drive of risk and achievement ultimately fosters Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, which inhibits adolescent autonomy and increases impulsivity levels43,44. From the perspective of the micro-level pathways of the GAM’s cognitive-emotional system, this influence operates through two primary mechanisms: (1) The behavioral deprivation mechanism: Consolidated Helicopter Parenting’s overprotectiveness deprives adolescents of opportunities to make autonomous decisions and bear consequences, leading to delayed development in inhibitory control within executive functions. Consequently, when adolescents encounter minor conflicts in sports, the lack of experience in calmly evaluating and rationally responding leads to impulsive reactions45,46. (2) The neurophysiological inhibition mechanism: Over-controlling psychological interventions inhibit the development of the prefrontal cortex in adolescents, a brain region central to suppressing aggressive impulses in the GAM model. Diminished function in this region impairs an individual’s ability to control impulsive aggression in conflict situations, further amplifying adolescent impulsivity47,48. The core features of Consolidated Helicopter Parenting are excessive protection and control, which deprive adolescents of opportunities to practice autonomous decision-making and emotional regulation, thereby hindering the development of their self-regulation abilities10,42. Consolidated Helicopter Parenting shows a significant positive correlation with all dimensions of the Brief Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, particularly in conflict resolution situations, where adolescents’ behavioral inhibition abilities are notably diminished49. Adolescent impulsivity, as an individual trait, directly drives the occurrence of aggressive behavior. According to the cognitive-emotional pathway of the GAM model, individuals with high adolescent impulsivity are prone to hostile attribution bias in conflict situations (e.g., interpreting an unintentional collision as deliberate provocation), with a significant reduction in the prefrontal cortex’s inhibitory control over aggressive behavior50. Based on this, Hypothesis 4 proposes that Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and adolescent impulsivity play a chain-mediated role in the effect of physical activity on adolescent aggressive behavior.

In light of this, we have developed the hypothesized model presented in Fig. 1.

Methods

Study population

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Vocational Institute of Electromechanical Technology (Approval No. 2024117), adhering strictly to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.Utilizing Kendall’s formula and considering the number of items in our study sur-vey, a preliminary estimate of the required sample size was calculated to be 5–10 times the number of study variables51. To account for the potential loss of questionnaire responses, an additional 30% of the sample size was added. Consequently, the formula for calculating the sample size in this study was: n = 10 × number of variables/(1–30%). This resulted in a minimum sample size of 515. From October to December 2024, a stratified cluster random sampling method was employed to survey 12 secondary schools in Hunan, Hubei, and Henan provinces (Hunan: 4 schools, Hubei: 3 schools, Henan: 5 schools). The survey was distributed and collected online using the Questionnaire Star platform. Participants ranged in age from 13 to 18 years, with 2794 male and 2019 female respondents. In terms of school type, 80.8% (3891 students) attended public schools, while 19.1% (922 students) attended private schools. Schools were classified as provincial key, municipal key, and regular schools, comprising 30.0%, 40.0%, and 30.0% of the total, respectively. Regarding family income, 74.15% (3569 participants) had a monthly household income between 5001 and 15,000 yuan. Parent occupations included 35.09% (1689 individuals) in manual labor, 39.39% (1896 individuals) in professional technical positions, and 25.51% (1228 individuals) in management. As for parental education level, 45.06% (2169 individuals) held a bachelor’s degree or higher, 33.16% (1596 individuals) had completed high school or vocational education, and 21.77% (1048 individuals) had an education level below junior high.Prior to survey distribution, the research team obtained electronic written consent from the school administration, class teachers, and students’ parents, informing students of their right to withdraw from the survey at any time. The research team provided standardized training for the class teachers responsible for implementation, clarifying instructions and key considerations. To minimize potential academic pressure, students in their final year of high school (Grade 12) and junior high school (Grade 9) were excluded from the survey. The sampling process included: (1) On-site training of class teachers by the research team; (2) Class teachers distributing the survey link in class groups and reiterating confidentiality principles; (3) An informed consent form attached to the survey’s first page, outlining the research purpose, anonymization procedures, and data usage scope. The survey design took approximately 12 min, incorporating three attention-check questions to eliminate invalid responses. After the class teachers collected the surveys online, two independent researchers exported and cross-checked the data. A total of 5288 surveys were collected, and after eliminating invalid and incomplete responses through attention-check questions and logical validation, 4813 valid samples were retained, resulting in a response rate of 91.01%.

Measurement tools

Physical activity

We employed the Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3), revised by Professor Liang Deqing’s team, to evaluate the physical activity levels of students52. The scale assesses several variables, including exercise intensity, duration, and frequency. The formula for calculating each individual’s total physical activity (PA) is PA = intensity (1–5) × duration (1–5) × frequency (0–4). As a result, the total PA ranged from 0 to 100. Three PA levels were identified: low (≤ 19), moderate (20–42), and high (≥ 43). The scale has been previously administered to a Chinese population53, and the CFA model indicates a good fit: χ2/df = 198.987, IFI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.031, SRMR = 0.038. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.615.

Aggressive behaviour

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ), revised by Liu Junsheng et al.54, was used in this study. The scale utilizes a 5-point Likert scoring system and is suitable for elementary to high school populations. The BPAQ comprises four dimensions: Physical Aggression, Hostility, Anger, and Verbal Aggression, with a total of 20 items. Higher scores indicate more severe aggressive behavior. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model shows a good fit, with the following indices: χ2/df = 179.216, IFI = 0.912, RMR = 0.033, and SRMR = 0.040. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were as follows: Physical Aggression = 0.791, Verbal Aggression = 0.844, Anger = 0.766, Hostility = 0.925, and the overall scale = 0.939.

Consolidated helicopter parenting

The Consolidated Helicopter Parenting Scale was adapted from the Bradley-Geist55 revised questionnaire, with translation adjustments made to maintain the original meaning, while aligning with Chinese cultural context and linguistic characteristics. The final version resulted in a Chinese scale with consistent items and scoring system as the original. This scale examines children’s perceptions of helicopter parenting, specifically measuring the extent to which parents influence important decisions made by their children. The scale uses a 5-point Likert scoring system: "1" indicates "Strongly Disagree," "2" indicates "Disagree," "3" indicates "Neutral," "4" indicates "Agree," and "5" indicates "Strongly Agree." Higher scores indicate a higher degree of helicopter parenting. The scale has been previously validated in a Chinese population10, with a CFA model showing a good fit: χ2/df = 275.942, IFI = 0.944, RMR = 0.024, SRMR = 0.031. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.949.

Adolescent impulsivity

The Brief Barratt Impulsiveness Scale is adapted from the questionnaire developed by Steinberg and Morean31,32, following Chinese cultural and linguistic nuances. The scale was translated with careful adjustments to ensure the meaning remained unchanged, resulting in a Chinese version that is consistent with the original items and scoring system. The scale consists of two dimensions: poor self-control and adolescent impulsivity, comprising a total of eight items. The scale has been previously validated in a Chinese population56, with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showing a good model fit: χ2/df = 100.129, IFI = 0.948, RMR = 0.019, SRMR = 0.026. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for poor self-control was 0.925, for adolescent impulsivity was 0.853, and for the total scale was 0.935.

Data processing

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software, and the PROCESS macro was employed to test for mediation effects. The results showed that Harman’s single-factor test was employed. The analysis revealed that, without conducting principal component factor rotation, three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were identified. The variance explained by the first factor (35.988%) was below the 40% threshold57. As a result, this study did not show significant common method bias.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

To examine the relationships between physical activity, consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and adolescent aggressive behavior, a correlation analysis was conducted for the four variables. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients between the variables. Physical activity showed positive correlations with consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and adolescent aggressive behavior. Strong positive correlations were observed between consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and adolescent aggressive behavior.

Mediating effect analysis

Table 2 reveals the predictive relationships among variables and the characteristics of mediating pathways, thereby validating Hypothesis 1.physical activity directly predicted consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and adolescent aggressive behavior. Consolidated helicopter parenting strongly predicted adolescent impulsivity, while adolescent impulsivity was the strongest predictor of adolescent aggressive behavior. This suggests that adolescent impulsivity may play a central mediating role in the path “physical activity → consolidated helicopter parenting → adolescent impulsivity → adolescent aggressive behavior.” All models passed the statistical significance tests, and the results were statistically significant.

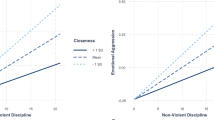

The chain mediation effect was tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro, specifically Model 6, which is suitable for analyzing the chain path X → M1 → M2 → Yʹ58. In the analysis, gender, age, and grade were controlled as covariates. A bootstrap procedure with 5,000 iterations was used to compute the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (BC 95% CI). If the CI did not contain 0, the mediation effect was considered significant. The results indicated a significant total indirect effect (Effect = 0.031, Boot SE = 0.013, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.052]). The core chain path (Physical activity → Consolidated Helicopter Parenting → Adolescent impulsivity → Aggressive behaviour) also showed a significant effect (Effect = 0.019, Boot SE = 0.011, 95% CI = [0.018, 0.069]), with the CI excluding 0, confirming the chain mediation effect. Table 3 presents the mediation analysis results, which support Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4.Tthe indirect effect of physical activity on adolescent aggressive behavior is primarily mediated through three pathways, with the chain mediation path “physical activity → consolidated helicopter parenting → impulsivity → adolescent aggressive behavior” being the strongest, representing the core mediating mechanism of the indirect effect; while the path “physical activity → consolidated helicopter parenting → adolescent aggressive behavior” showed the weakest effect. The overall indirect effect was significant (Effect = 0.031, 95% CI [0.010, 0.052]), suggesting that the mediators (consolidated helicopter parenting, adolescent impulsivity) played a crucial role in the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior, providing empirical evidence for understanding the underlying mechanism of their relationship.

In the section on mediation analysis, we have included the calculation of standardized effects. To better illustrate the relative influence of the variables and the practical significance of the results, we further computed the standardized effects. The results of these calculations are presented in the Table 4 below.

Table 4 results of the standardized effects indicate that the serial mediation effect is the strongest among all pathways. This further confirms that the serial mediation pathway from physical activity, through consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity, to aggressive behavior is particularly significant. Although the total indirect effect remains relatively small, the standardized effect allows for a more accurate assessment of the role of each variable in the overall process.

Discussion

It is essential to recognize that the total indirect effect (0.031) obtained in this study is relatively low. This phenomenon can be explained from various perspectives. First, the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior is not direct but is mediated by consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity. Consequently, the effect weakens through these multiple stages of mediation. Second, adolescent impulsivity is a complex behavior influenced by multiple interacting factors, such as genetic predispositions, family environment, school atmosphere, and peer relationships. These factors result in a limited effect from a singular mediation pathway. This result highlights the need to avoid overestimating the impact when interpreting the research findings.

The impact of physical activity on aggressive behaviour in adolescents

This study found that physical activity positively predicts adolescent aggressive behavior; specifically, higher levels of physical activity are associated with increased tendencies toward aggression, confirming Hypothesis 1. Although this finding appears to contradict the conventional view that physical activity promotes emotional regulation, it highlights the critical influence of activity type and situational norms59,60. According to the General Aggression Model (GAM),Within this study’s sample, adolescents reported physical exercise predominantly concentrated at ≥ 3 sessions per week, each lasting ≥ 30 min of high-intensity activity. This aligns closely with the implicit premise of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, resistance-related exercise. high-intensity, competitive physical activities involving frequent physical contact and win-loss scenarios activate aggression cues, which, if not properly managed, may generalize to daily life, thereby increasing aggressive behavior. Research has shown that brief exposure to competitive video games elevates adolescents’ immediate impulsive responses and aggressive behavior, with adolescent impulsivity serving as a mediator7. Similarly, the immediate feedback characteristic of contact sports may reinforce impulsive response patterns, increasing the likelihood of aggressive strategies during conflicts33,61,62. Previous studies have found that non-competitive physical activities can reduce aggressive behavior37,43, whereas our positive findings suggest that the relationship between physical activity and aggression is not intrinsic but moderated by activity intensity and rule enforcement. For instance, traditional Chinese martial arts emphasize moral cultivation (“wude”), which reduces aggression by enhancing self-control and alleviating depression; however, competitive martial arts lacking such moral training may increase aggression due to an overemphasis on winning63,64,65. Furthermore, in highly competitive matches, when coaches excessively emphasize a "win-at-all-costs" mentality, the competition itself may act as a reinforcement for aggressive behavior, consistent with the theory of situational cues activating aggressive actions66,67,68.

The mediating role of consolidated helicopter parenting in physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour

This study found that physical activity influences adolescent aggressive behaviour through the mediating role of consolidated helicopter parenting. Physical activity has a direct effect on aggressive behaviour, while consolidated helicopter parenting transmits the effect between physical activity and aggressive behaviour (effect = 0.002 for Physical activity ⇒ Consolidated Helicopter Parenting ⇒ Aggressive behaviour). Thus, consolidated helicopter parenting partially mediates the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour. These findings support Hypothesis 2, which posits that consolidated helicopter parenting partially mediates the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour.From the perspective of family systems theory, the competitiveness and potential risks associated with physical activity (such as sports injuries and losses in competitions) significantly enhance parents’ perception of risk, prompting them to engage in more frequent intervention behaviors. Research has shown that parental over-involvement in physical activity directly impairs adolescents’ emotional regulation, making them more prone to aggression in conflict situations69,70. Such interventions not only limit adolescents’ opportunities to cope independently with setbacks during physical activities but also create a vicious cycle through the path "overprotection → low autonomy → increased aggressive behavior." Further analysis revealed that the type of physical activity moderates the strength of the mediation effect of consolidated helicopter parenting71,72. For example, in high-intensity competitive sports, parents perceive the risks associated with physical contact more strongly, leading them to adopt more stringent control measures, which significantly inhibit the development of adolescents’ conflict-resolution skills73,74. In contrast, non-competitive sports, with lower risks, result in less parental intervention, and the mediation effect is not significant75. These results align with the theory of "situational risk activating family control"74, which posits that the inherent risks in physical activity serve as a critical trigger for consolidated helicopter parenting. Over-intervention deprives adolescents of opportunities to make independent decisions, hindering the development of constructive coping strategies during conflicts in physical activities, leading to the reliance on aggressive behaviors to express emotions. Studies have shown that consolidated helicopter parenting significantly reduces adolescents’ satisfaction with basic psychological needs (particularly autonomy), and this lack of need fulfillment directly translates into a desire to control others, leading to stronger aggressive behaviors during sports conflicts and feelings of resentment, which may manifest as verbal or physical aggression23,71,76. Excessive parental protection diminishes adolescents’ emotional self-regulation abilities77,78. Research also indicates that consolidated helicopter parenting increases adolescents’ vulnerability to emotional dysregulation, particularly in stressful situations. This effect is further amplified in high-intensity physical activities79,80. For example, adolescents raised in overprotective environments may react with intense anger when faced with a loss in competition, as they lack the experience to cope with failure. This pattern of behavior may extend to daily social interactions. The mediation effect identified in this study is particularly pronounced in collectivist cultural contexts. The intergenerational dependency tradition in Chinese families, coupled with the educational expectation of hoping for one’s child to succeed, leads parents to be more inclined to intervene excessively to reduce the risk of failure in various activities. This cultural specificity reinforces the pathway of "physical activity → consolidated helicopter parenting → aggressive behavior."

The mediating role of adolescent impulsivity between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour

Physical activity has a direct effect on aggressive behaviour, while adolescent impulsivity mediates the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behaviour (effect = 0.01 for Physical activity ⇒ Adolescent impulsivity ⇒ Aggressive behaviour). Thus, adolescent impulsivity partially mediates the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behaviour, confirming Hypothesis 3.From the General Aggression Model (GAM), the physical contact and competitive scenarios in high-intensity confrontational physical activities activate an immediate response mode. When combined with adolescent impulsivity, this mode may generalize to conflict situations in daily life. Previous studies have found that exposure to competitive video games increases adolescent aggression through the mediation of adolescent impulsivity7,81. This mechanism is similarly applicable to competitive contexts within physical activity. The demands for rapid offense-defense transitions in confrontational sports reinforce adolescents’ tendency for instant gratification, making them more prone to aggressive responses when facing setbacks. The quick-response requirement in such activities strengthens the immediacy of adolescents’ actions82, and when combined with adolescent impulsivity, this behavior pattern makes aggressive behavior more likely to be triggered83. For instance, the quick retaliation behavior in contact sports may transfer to everyday conflicts, prompting adolescents to act impulsively when angered, thus supporting the applicability of the behavioral generalization theory in aggression research. Previous studies have shown that deficits in executive functions are a deep-rooted cause of adolescent impulsivity84,85. High-intensity stimuli in physical activity may further impair executive functions86,87. For example, frequent quick decision-making and physical confrontations in basketball deplete cognitive resources, which may hinder the ability to delay gratification in subsequent conflict situations. This pathway of "executive function depletion → increased adolescent impulsivity" aligns with Baumeister et al.'s88 self-control theory, which posits that high demands in physical activity can lead to temporary depletion of self-regulation resources, making aggressive behavior more easily triggered.

The chain-like mediating effect of consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour

This study provides the first empirical validation of the chained mediating effect of Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and Adolescent Impulsivity between Physical Activity and Adolescent Aggressive Behavior. Specifically, Physical Activity triggers Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, which enhances Adolescent Impulsivity, ultimately leading to the externalization of Aggressive Behavior in adolescents. This finding challenges the traditional focus on a single mediating variable in prior research, revealing a multi-level transmission mechanism of “contextual stimuli → family intervention → individual adaptation.” The chain mediation effect identified in this study can be further elucidated through core evidence from sports neuroscience, particularly regarding the inhibitory function of the prefrontal cortex. The structure and functional status of the prefrontal cortex—especially the DLPFC and vmPFC—serve as critical neural links between parenting behaviours and adolescent aggression tendencies48. Developmental neuroscience research confirms that the maturation of the adolescent DLPFC is dependent on autonomous decision-making and repeated feedback from consequences. When individuals autonomously address challenges in physical activities, the DLPFC strengthens synaptic connections through sustained activation, thereby enhancing the ability to inhibit impulsive responses and plan rational behaviours89,90. In contrast, the integrated form of consolidated helicopter parenting (overprotection and excessive control) in this study deprives adolescents of such crucial practices46,91.From the perspective of family systems theory, the adversarial risks inherent in Physical Activity activate parents’ protective instincts, leading them to engage in frequent intervention behaviors. Previous research indicates that Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, characterized by excessive intervention and low autonomy support, undermines adolescent autonomy and a sense of competence, thereby fostering externalizing behavioral problems92. This study is the first to incorporate this construct into the Physical Activity-Aggressive Behavior model, finding that adolescents with higher levels of Physical Activity are more likely to perceive excessive parental involvement, which in turn increases their tendency towards aggression. A possible explanation is that Physical Activity provides psychological resources such as autonomy, competence, and belonging. In the absence of these resources, adolescents become more sensitive to suffocating parental care, leading to aggression as a means of seeking control or venting frustration. The study further reveals that Consolidated Helicopter Parenting indirectly exacerbates Aggressive Behavior by increasing Adolescent Impulsivity. This finding resonates with Patock-Peckham et al.'s93 study on college students with alcohol use issues, which found that parental control diminishes impulse control, leading to externalizing problems. During adolescence, the prefrontal cortex is not fully mature, and impulse control relies primarily on external support and self-practice94. Consolidated Helicopter Parenting limits opportunities for independent decision-making, inhibiting the development of self-regulation skills and making Adolescent Impulsivity a critical proximal factor in Aggressive Behavior95,96.

Research limitations

Firstly, this study employed a crosssectional research design, analyzing relationships between variables through one-time data collection. This design limits our understanding of causality. Future research could employ longitudinal research designs to track changes in individuals over time to explore the causal relationships between these variables.Secondly, this study used a single self-report scale to measure Physical activity, Aggressive behaviour, Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, and Adolescent impulsivity. Although these scales are widely used in psychological research and have reliability and validity,they still rely on self-reported data and may be subject to selfreport biases. Future research could consider using multiple data sources, such as observations, peer evaluations, or objective measurement tools, to collect more comprehensive data.Lastly, the relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior may be influenced by various factors. While the findings of this study are insightful, caution should still be exercised. Due to the limitations of this study, these findings require further validation through longitudinal studies and the application of multiple research methods. Longitudinal studies could track changes in aggressive behavior over time as adolescents engage in different forms of physical activity, providing a more accurate understanding of the dynamic relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior. The integration of various research methods, such as behavioral observation and physiological measurements, would offer a more comprehensive dataset, facilitating a deeper understanding of the chain-mediated mechanisms involving consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity in the relationship between physical activity and aggressive behavior. Therefore, while the results of this study are promising, further rigorous research is needed to confirm these findings.Additionally, the discriminant validity of the scales used in this study warrants further attention. Given the high correlation between Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and adolescent impulsivity, this suggests potential limitations in the ability of the scales to differentiate between these two constructs. Ideally, separate scales should accurately measure distinct constructs; however, the observed high correlation may indicate that certain items capture similar information, leading to insufficient differentiation between the constructs. For instance, some items in the Consolidated Helicopter Parenting scale measuring parental overprotection may overlap with items in the adolescent impulsivity scale that reflect a lack of self-control, potentially reflecting similar psychological states. This overlap may introduce bias in evaluating the independent effects of these constructs, as well as their chain mediation role between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behaviour. Future research should implement more rigorous scale development and validation procedures to enhance discriminant validity and more precisely assess the relationships between these constructs.

Theoretical discussion

Distinction from Social Learning Theory: Social Learning Theory posits that individuals learn by observing and imitating others, with aggressive behavior being acquired through observing and receiving reinforcement for such behaviors97. The theory emphasizes the process of observing and imitating external models, along with the reinforcement mechanisms involved in this learning process. For instance, children may imitate violent behaviors portrayed by characters on television, and if such behaviors are rewarded or receive attention, the likelihood of exhibiting aggressive behavior again increases.In contrast, the model used in this study incorporates Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and Adolescent Impulsivity as chained mediators between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior within the General Aggression Model (GAM). This model focuses on how family environment (Consolidated Helicopter Parenting) influences individual psychological traits (Adolescent Impulsivity), and how these traits, in turn, affect adolescent aggressive behavior in physical activity contexts. It extends beyond merely observing and imitating external behaviors, delving into the psychological and familial factors that contribute to the development of aggressive behavior.For example, Consolidated Helicopter Parenting may limit adolescents’ autonomy, thereby influencing the development of their Adolescent Impulsivity traits, which subsequently affects their aggressive behavior during physical activity. This differs significantly from the Social Learning Theory, which solely emphasizes external observation and imitation.

Distinction from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory: Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory examines individual development within a multi-layered ecological system, encompassing micro, meso, exo, and macro systems, and emphasizes the interaction between these layers in shaping individual development98. The theory focuses on the individual’s entire ecological environment, ranging from micro-level contexts such as family and school to macro-level influences like socio-cultural factors.While this study’s model incorporates family environment (Consolidated Helicopter Parenting) as a factor, it primarily focuses on how parenting behaviors influence adolescent impulsivity, acting as a chain mediator between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior. Unlike Ecological Theory, which considers the interaction of multiple ecological layers, this model focuses more narrowly on how parenting behaviors and individual psychological traits influence aggressive behavior in specific contexts (e.g., physical activity).For example, this study focuses on how specific parenting behaviors, such as Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, shape adolescent impulsivity, subsequently influencing aggressive behavior during physical activity. In contrast, Ecological Theory considers the interaction of various factors, including family, school, community, and socio-cultural influences.

Conclusions and recommendations

The results of this study indicate a certain relationship between physical activity and adolescent aggressive behavior, although this relationship is not as straightforward as suggesting that all forms of physical activity promote aggression. Specifically, certain types of physical activity, such as high-intensity, competitive, and contact-based activities, may be associated with a higher risk of aggressive behavior under certain conditions. For example, in intense competitive sports, when athletes face significant pressure and the stakes of the competition are high, the combination of emotional tension and desire to win may lead to increased aggression. Conversely, non-competitive activities that emphasize relaxation and cooperation, such as yoga and tai chi, are less likely to provoke aggression and may even contribute to a reduction in aggressive behavior. Moreover, the direct effect of physical activity on aggressive behavior in this study was relatively small, with most of the impact mediated by the roles of consolidated helicopter parenting and adolescent impulsivity. This study employed a chain-mediation model to explore the relationships between Physical Activity, Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, Adolescent Impulsivity, and Adolescent Aggressive Behavior, revealing that Physical Activity is positively correlated with Aggressive Behavior. This relationship is not direct but is mediated through the pathway: "Physical Activity → Consolidated Helicopter Parenting → Adolescent Impulsivity → Aggressive Behavior." Specifically, high-risk, high-aggression Physical Activity may trigger excessive parental concern, leading to more frequent interventions. Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, in turn, suppresses adolescent autonomy, thereby enhancing Adolescent Impulsivity traits. Ultimately, higher Adolescent Impulsivity further amplifies the tendency for Aggressive Behavior in conflict situations. This study enriches the General Aggression Model (GAM) by integrating the "Context-Family-Individual" interaction mechanism. GAM posits that aggressive behavior is a dynamic process involving "input variables (contextual cues, individual traits) → internal states (cognition, emotion, arousal) → output behavior." Previous studies have largely focused on singular contextual or individual factors, overlooking the mediating role of the family system. By incorporating the chain-mediation model, this study integrates Physical Activity (context), Consolidated Helicopter Parenting (family system), and Adolescent Impulsivity (individual traits) into the GAM framework, revealing a pathway where external contexts, via family intervention, influence internal states, ultimately triggering aggressive behavior. This addresses the underemphasis on the family system in GAM, offering a new perspective on the nested causes of aggressive behavior.

Based on the research findings, the following recommendations are proposed: Develop parental education programs to avoid excessive control in sports activities.Establish school guidelines to promote cooperative activities (non-competitive sports, yoga, martial arts with an ethical component).Propose multi-level interventions (family–school–community) to reduce the risks of aggression linked to physical activity.

Research outlook

This study incorporates the family system into the General Aggression Model (GAM) as a chain mediator, with the model potentially displaying different outcomes and significance across various cultural contexts, offering valuable directions for future research. In collectivist cultural contexts, such as many Asian countries, the concept of family is typically more pronounced, playing a crucial role in individual development. The manifestation of Consolidated Helicopter Parenting may differ from that in individualistic cultures, possibly emphasizing family honor and collective interests. Parental control and protection may also focus more on preserving the family’s overall image. In this cultural context, future research can explore how Consolidated Helicopter Parenting interacts with collectivist values, influencing adolescent impulsivity and aggressive behavior. For example, research could investigate whether excessive parental protection in collectivist cultures is accepted by adolescents due to the emphasis on collective interests, thereby affecting adolescent impulsivity and aggressive behavior differently from individualistic cultures. In individualistic cultural contexts, such as in some Western countries, emphasis on personal freedom and independence may lead to Consolidated Helicopter Parenting being viewed as an infringement on individual liberty. Adolescents may develop stronger resistance to this parenting style, potentially further influencing their impulsivity and aggressive behavior. Future research could examine how adolescents in individualistic cultures respond to Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and how such responses affect their aggressive behavior in physical activity contexts. Additionally, physical activity varies across cultures in terms of characteristics and values. In some cultures, physical activity emphasizes teamwork and friendship, while in others, competition and victory are more highly valued. These differing values of physical activity may interact with Consolidated Helicopter Parenting and adolescent impulsivity, influencing aggressive behavior. Future research could delve deeper into how physical activity cultures across different cultures mediate the chain effect between Consolidated Helicopter Parenting, adolescent impulsivity, and aggressive behavior in physical activity (Supplementary Information).

Data availability

Due to the nature of this study, participants in this study did not agree to share their data publicly and therefore supporting data could not be provided. If anyone would like to obtain data from this study, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Piko, B. F. & Pinczés, T. Impulsivity, depression and aggression among adolescents. Pers. Individ. Differ. 69, 33–37 (2014).

Muarifah, A. et al. Aggression in adolescents: the role of mother-child attachment and self-esteem. Behav. Sci. 12(5), 147 (2022).

López, E. E. et al. Adolescent aggression: Effects of gender and family and school environments. J. Adolesc. 31(2), 433–450 (2008).

UNESCO. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status and Trends, Drivers and Consequences. [R/OL]. https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/library/documents/school-violence-and-bullying-global-status-and-trends-drivers-and-consequences (2018).

Biddle, S. J. H. & Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 45(11), 886–895 (2011).

Zhaohui, L. Effects of physical exercise on negative emotion for university students—The mediating and moderating effects of self-efficacy and mental resilience. J. Phys. Educ. 27(05), 102–108 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. Competitive video game exposure increases aggression through impulsivity in Chinese adolescents: evidence from a multi-method study. J. Youth Adolesc. 53(8), 1861–1874 (2024).

Anderson, C. A. & Bushman, B. J. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychol. Sci. 12(5), 353–359 (2001).

Cui, M. et al. Indulgent parenting, helicopter parenting, and well-being of parents and emerging adults. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28(3), 860–871 (2019).

Gao, W. et al. Helicopter parenting and emotional problems in Chinese emerging adults: Are there cross-lagged effects and the mediations of autonomy?. J. Youth Adolesc. 52(2), 393–405 (2023).

Fite, P. J. & Vitulano, M. Proactive and reactive aggression and physical activity. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 33(1), 11–18 (2011).

Dayton, C. J. & Malone, J. C. Development and socialization of physical aggression in very young boys. Infant. Ment. Health J. 38(1), 150–165 (2017).

Wade, L. et al. Mediators of aggression in a school-based physical activity intervention for low-income adolescent boys. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 14, 39–46 (2018).

Bushman, B. J. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28(6), 724–731 (2002).

Anderson, C. A. & Bushman, B. J. Human aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53(1), 27–51 (2002).

Eime, R. et al. Psychological and social benefits of sport participation: The development of health through sport conceptual model. J. Sci. Med. Sport 16, e79–e80 (2013).

Reynes, E. & Lorant, J. Effect of traditional judo training on aggressiveness among young boys. Percept. Mot. Skills 94(1), 21–25 (2002).

Carroll, J. S. et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of contact sports participation on adolescents’ attitudes toward violence. J. Youth Adolesc. 35(3), 427–436 (2006).

Selmi, O. et al. High intensity interval training negatively affects mood state in professional athletes. Sci. Sports 33(4), e151–e157 (2018).

Endresen, I. M. & Olweus, D. Participation in power sports and antisocial involvement in preadolescent and adolescent boys. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46(5), 468–478 (2005).

LeMoyne, T. & Buchanan, T. Does, “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociol. Spectr. 31(4), 399–418 (2011).

Broderick, C. B. Understanding Family Process: Basics of Family Systems Theory (Sage, 1993).

Macias, L. Helicopter Parenting and the Relationship to Health Behaviors During Emerging Adulthood (Palo Alto University, 2019).

Bi, X. et al. Parenting styles and parent-adolescent relationships: the mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Front. Psychol. 13(9), 2187 (2018).

Holt, N. L., Tamminen, K. A., Black, D. E., Mandigo, J. L. & Fox, K. R. Youth sport parenting styles and practices. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 31(1), 37–59 (2009).

Masud, H., Ahmad, M. S., Cho, K. W. & Fakhr, Z. Parenting styles and aggression among young adolescents: a systematic review of literature. Community Ment Health J 55(6), 1015–1030 (2019).

Wang, M. Harsh parenting and adolescent aggression: Adolescents’ effortful control as the mediator and parental warmth as the moderator. Child Abuse Negl. 94, 104021 (2019).

Kokkinos, C. M., Algiovanoglou, I. & Voulgaridou, I. Emotion regulation and relational aggression in adolescents: parental attachment as moderator. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 3146–3160 (2019).

Vega, A., Cabello, R., Megías-Robles, A., Gómez-Leal, R. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. Emotional intelligence and aggressive behaviors in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 23(4), 1173–1183 (2022).

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51(6), 768–774 (1995).

Steinberg, L. et al. New tricks for an old measure: The development of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief (BIS-Brief). Psychol. Assess. 25(1), 216 (2013).

Morean, M. E. et al. Psychometrically improved, abbreviated versions of three classic measures of impulsivity and self-control. Psychol. Assess. 26(3), 1003–1020 (2014).

González-Hernández, J., Capilla Díaz, C. & Gómez-López, M. Impulsiveness and cognitive patterns. Understanding the perfectionistic responses in Spanish competitive junior athletes. Front. Psychol. 10, 1605 (2019).

Costa, K. M. et al. Mood state, motivation and impulsiveness among students participating in youth school games. J. Phys. Educ. 32, e3235 (2021).

Huđin, N., Glavaš, D. & Pandžić, M. Contact sports as a sport of more aggressive athletes? Aggressiveness and other psychological characteristics of youth athletes involved in contact and non-contact sports. Tims Acta naučni časopis za sport, turizam i velnes 14(1), 5–16 (2020).

Albouza, Y., Wach, M. & Chazaud, P. Personal values and unsanctioned aggression inherent in contact sports: the role of self-regulatory mechanisms, aggressiveness, and demographic variables. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 70(3), 100550 (2020).

Javelle, F. et al. Physical exercise is tied to emotion-related impulsivity: insights from correlational analyses in healthy humans. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 23(6), 1010–1017 (2023).

Stanford, M. S. et al. Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Pers. Individ. Differ. 47(5), 385–395 (2009).

Xie, H., Cairns, R. B. & Cairns, B. D. The development of social aggression and physical aggression: A narrative analysis of interpersonal conflicts. Aggress. Behav. 28(5), 341–355 (2002).

Leasure, J. L. & Neighbors, C. Impulsivity moderates the association between physical activity and alcohol consumption. Alcohol 48(4), 361–366 (2014).

Kotbagi, G. et al. Which dimensions of impulsivity are related to problematic practice of physical exercise?. J. Behav. Addict. 6(2), 221–228 (2017).

La Rosa, V. L., Ching, B. H. H. & Commodari, E. The impact of helicopter parenting on emerging adults in higher education: A scoping review of psychological adjustment in university students. J. Genet. Psychol. 186(2), 162–189 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Effects of sports intervention on aggression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 11, e15504 (2023).

Sagar, S. S. & Lavallee, D. The developmental origins of fear of failure in adolescent athletes: Examining parental practices. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 11(3), 177–187 (2010).

Barber, B. K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 67(6), 3296–3319 (1996).

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Son, D. & Nelson, L. J. Profiles of helicopter parenting, parental warmth, and psychological control during emerging adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 9(2), 132–144 (2021).

Zelazo, P. D. & Müller, U. Executive function in typical and atypical development. Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. 445–469 (2002).

Weinberger, D. R., Elvevåg, B. & Giedd, J. N. The Adolescent Brain, Vol. 1, 10–12 (National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 2005).

Grolnick, W. S., Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective. Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory, 44, 135–161 (1997).

Buckholtz, J. W. et al. The neural correlates of third-party punishment. Neuron 60(5), 930–940 (2008).

Wang, J. L. Clinical Epidemiology: Clinical Research Design, Measurement and Evaluation (Scientific & Technical Publishers, 2014).

Liang, D. Stress levels of students in higher education and their relationship with physical activity. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1, 5–6 (1994).

Peng, J. et al. Mobile phone addiction was the mediator and physical activity was the moderator between bullying victimization and sleep quality. BMC Public Health 25(1), 1–13 (2025).

Liu, J. S., Zhou, Y. & Gu, W. Y. Preliminary revision of the Buss-Perry Aggression Scale in adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 17(04), 449–451 (2009).

Bradley-Geist, J. C. & Olson-Buchanan, J. B. Helicopter parents: An examination of the correlates of over-parenting of college students. Educ. Train. 56(4), 314–328 (2014).

Leng, J. et al. Test of reliability and validity of impulsiveness scale among married Chinese. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 903–912 (2022).

Podsakof, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakof, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879 (2003).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Publications, 2017).

Iannotti, R. J. et al. Patterns of adolescent physical activity, screen-based media use, and positive and negative health indicators in the US and Canada. J. Adolesc. Health 44(5), 493–499 (2009).

Bredemeier, B. J. et al. The relationship of sport involvement with children’s moral reasoning and aggression tendencies. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 8(4), 304–318 (1986).

Chauhan, V. S. 15 neurophysiological basis of athletic performance. Innov. Res. 106 (2025).

Smith, R. E. & Smoll, F. L. Sport performance anxiety. In Handbook of Social and Evaluation Anxiety (Springer US, 1990).

Xu, T. et al. Exploring the impact of traditional Chinese martial arts and other martial arts on adolescent aggression: a comparative analysis of underlying mechanisms. BMC Psychol. 13(1), 352 (2025).

Lafuente, J. C., Zubiaur, M. & Gutiérrez-García, C. Effects of martial arts and combat sports training on anger and aggression: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent. Beh. 58, 101611 (2021).

Xu, T. et al. The effects of self-control on bullying behaviour among martial arts practicing adolescents: based on the analyses of multiple mediation effects. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 22(1), 92–105 (2024).

May, R. A. B. The sticky situation of sportsmanship: Contexts and contradictions in sportsmanship among high school boys basketball players. J. Sport Soc. Issues 25(4), 372–389 (2001).

Schuette, J. R. Adolescent sports violence-when prosecutors play referee. Making criminals out of child athletes, but are they the real culprits. N. Ill. UL Rev 21, 515 (2001).

Spiller, V. Young People’s Perceptions and Experiences of Their Physical Bodies (Victoria University, 2009).

Holt, N. L. et al. Parental involvement in competitive youth sport settings. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 9(5), 663–685 (2008).

Bonavolontà, V. et al. The role of parental involvement in youth sport experience: Perceived and desired behavior by male soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(16), 8698 (2021).

Nie, T., Cai, M. & Chen, Y. An investigation of helicopter parenting and interpersonal conflict in a competitive college climate. Healthcare 11(19), 1484 (2023).

Jeanfreau, M. M., Holden, C. L. & Esplin, J. A. How far is too far? Parenting behaviors in youth sports. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 48(4), 356–368 (2020).

Carver, A. et al. Are children and adolescents less active if parents restrict their physical activity and active transport due to perceived risk?. Soc. Sci. Med. 70(11), 1799–1805 (2010).

Grolnick, W. S. The Psychology of Parental Control: How Well-Meant Parenting Backfires (Psychology Press, 2002).

Gustafson, S. L. & Rhodes, R. E. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Med. 36(1), 79–97 (2006).

Sadoughi, M. Overparenting and adolescent’s trait anxiety: Unraveling the roles of basic psychological needs frustration and emotion dysregulation. Acta Physiol. 251, 104579 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Associations between overprotective parenting style and academic anxiety among Chinese high school students. BMC Psychol. 13(1), 1–17 (2025).

Barros, L., Goes, A. R. & Pereira, A. I. Parental self-regulation, emotional regulation and temperament: Implications for intervention. Estudos de Psicologia 32, 295–306 (2015).

Khalid, K. & Akhtar, S. Perceived helicopter parenting, emotional regulation and social anxiety in adolescents. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 14(1), 1676–1686 (2025).

Smetana, J. G. Adolescents, Families, and Social Development: How Teens Construct Their Worlds (Wiley, 2010).

Adachi, P. J. C. & Willoughby, T. Demolishing the competition: The longitudinal link between competitive video games, competitive gambling, and aggression. J. Youth Adolesc. 42(7), 1090–1104 (2013).

Hern, M. One Game at a Time: Why Sports Matter (AK Press, 2013).

Hahn, A. M. et al. Prediction of verbal and physical aggression among young adults: A path analysis of alexithymia, impulsivity, and aggression. Psychiatry Res. 273, 653–656 (2019).

Romer, D. et al. Executive cognitive functions and impulsivity as correlates of risk taking and problem behavior in preadolescents. Neuropsychologia 47(13), 2916–2926 (2009).

Reynolds, B. W. et al. Executive function, impulsivity, and risky behaviors in young adults. Neuropsychology 33(2), 212 (2019).

Soga, K., Shishido, T. & Nagatomi, R. Executive function during and after acute moderate aerobic exercise in adolescents. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 16, 7–17 (2015).

Costello, S. E., O’Neill, B. V., Howatson, G., van Someren, K. & Haskell-Ramsay, C. F. Detrimental effects on executive function and mood following consecutive days of repeated high-intensity sprint interval exercise in trained male sports players. J. Sports Sci. 40(7), 783–796 (2021).

Baumeister, R. F. et al. Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. J. Pers. 74(6), 1773–1802 (2006).

Giedd, J. N. et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 2(10), 861–863 (1999).

Romine, C. B. & Reynolds, C. R. A model of the development of frontal lobe functioning: findings from a meta-analysis. Appl. Neuropsychol. 12(4), 190–201 (2005).

Ching, B. H. H., Li, Y. H. & Chen, T. T. Helicopter parenting contributes to school burnout via self-control in late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Curr. Psychol. 42(33), 29699–29711 (2023).

Kouros, C. D., Pruitt, M. M., Ekas, N. V., Kiriaki, R. & Sunderland, M. Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and college students’ mental health and well-being: the moderating role of sex and ethnicity. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 939–949 (2017).

Patock-Peckham, J. A. & Morgan-Lopez, A. A. College drinking behaviors: mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 20(2), 117 (2006).

Nigg, J. T. Annual research review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58(4), 361–383 (2017).

Padayichie, K. Guidance and Support Model to Assist Parents and Learners With Aggressive Behaviour (University of South Africa (South Africa), 2019).

Romm, K. F., Barry, C. M. N. & Alvis, L. M. How the rich get riskier: Parenting and higher-SES emerging adults’ risk behaviors. J. Adult Dev. 27(4), 281–293 (2020).

Bandura, A. & Walters, R. H. Social Learning Theory (Prentice Hall, 1977).

Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Harvard University Press, 1979).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their contributions to this research.

Funding

Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Science Youth Project "Number Intelligence Empowering College Students Physical Health Wisdom System Construction and Empirical Tracking Research" (23YJC890059).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mengfen, Jiawei and WenLie. conducted the research design, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript.Mengfen and WenLie. conceived the experiment. Mengfen, WenLie, Jiawei, Zeng and Shaokai analysed the results interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Hunan Mechanical & Electrical Polytechnic (2024117) prior to its commencement. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians who were willing to participate in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Chen, J., Qiu, J. et al. The chain mediating role of consolidated helicopter parenting and impulsivity in the physical activity to adolescent aggressive behavior. Sci Rep 15, 45565 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28567-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28567-5