Abstract

Identifying band-specific features —such as amplitude and latency/duration—from event-related desynchronization (ERD) patterns in MEG/EEG time-frequency representations can enhance our understanding of how the brain processes tasks and influences behavior. However, these features can be affected by potential noise, intrinsic instabilities, and inter-trial variability, which makes it challenging to analyze ERD dynamics accurately when multiple peaks with similar amplitudes emerge in the ERD pattern. To address these issues, we introduce SmartERD, a new pipeline designed to extract dynamic ERD features while considering ERD variability. SmartERD automatically estimates a band-specific pseudo-confidence interval around the absolute ERD peak, inspired by uncertainty propagation principles. It then identifies the first local ERD peak within this interval —representing the first component of the induced oscillatory response— and automatically extracts its features. A key advantage of this approach is that it extracts the latency of a common reference point for all subjects —the first peak response after a trigger— facilitating more consistent comparisons. We validated SmartERD through realistic simulations that mimic different trial numbers. Results showed that SmartERD’s estimates are closer to the ground truth across various noise levels compared to standard methods. Additionally, when applied to experimental MEG data, SmartERD demonstrated a better ability to capture individual differences in ERD dynamics, thanks to the selection of a common reference latency. Overall, we propose SmartERD as a valuable tool for extracting meaningful features from oscillatory dynamics, with the potential to improve the analysis of brain-behavior relationships in complex cognitive tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The MEG/EEG study of the dynamics of the rhythmical activity in the brain could provide information regarding the neural mechanisms underlying perceptual and cognitive operations in humans1,2,3. In this regard, the time-frequency representation (TFR) of the oscillatory activity can be achieved through different approaches, e.g. Short Term Fourier Transform (STFT)4, wavelet transform (typically a Morlet wavelet)5 multitaper2 or superlets6, estimated for each trial and averaged for each experimental condition during task. Especially in the alpha and beta bands, indices of stimulus-induced oscillatory modulations can be obtained from event-related desynchronizations (ERD), that are percentage variations relative the mean power-spectrum density over a pre-trigger epoch, or baseline7.

A popular approach to analyze the oscillatory dynamics is the identification, for each band, of dynamic features, like e.g. the absolute ERD peak (AEP) amplitude and the related most responsive frequency, the AEP latency8,9,10,11,12, onset, area, etc., that could be associated with different aspects of neural processing. Specifically, these separate parameters could be processed by a statistical analysis to compare conditions or subjects, automatically considering inter-subject differences in the ERD dynamics since the comparisons are rescaled at the subject-specific responsive frequency/latency. As example, the ERD amplitude and latency/duration were linked with the degree of involvement and the processing time of a brain region, respectively5,13,14.

In general, the reliability of feature extraction depends on various independent factors, that are critical especially when high-order areas are investigated. In this case, multiple peaks, representing different components of the response, may occur, making it difficult to select the representative ERD features. First, the estimator variance (noise) of the TFR method applied to the signals is unavoidable. This depends on the estimator parameters (e.g. the window size and type for STFT, the cycle number for wavelet transform) and could be decreased by averaging TFRs over trials. Second, residual noise due to sources external to brain (e.g. environmental noise, eye blinking, facial muscle and heart fields residuals even after artifact removal, see15 might modify the real power time-courses, potentially introducing false peaks and throughs at the single trial level, and thus reducing the SNR on the averaged TFR. Third, the inter-trial variability could smear or alter the average TFR patterns or the feature extraction. This variability may rely on physiological bases (e.g. changes of attention to the stimulus, habituation) and could be linked to behavior. However, single-trial feature analysis is hard due to the poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), thus multiple trials are averaged to ensure stable results.

Standard approaches for feature extraction (e.g., the AEP identification) have usually been applied without considering the contribution of these noise sources, representing a potential confounding factor for low number of trials and/or high inter-trial variability. An alternate procedure to analyze the ERD dynamics relies on the data-driven identification of significantly reactive time-frequency intervals from many bin-to-bin comparisons of the ERDgrams across conditions or subject groups. A standard procedure to solve the consequent multiple comparison issue is applying a nonparametric cluster-based permutation test (NPCPT)2,16, a non-parametric statistical test that operates on spectral-temporal connected clusters, previously identified based on spectral and temporal adjacency. Thus, NPCPT searches for time-frequency intervals with consistent ERDgram modulations across trials or subjects, but with limited sensitivity to inter-subject or inter-trial variability. This could influence the investigation of higher-order regions during complex cognitive tasks. Notably, the AEP latency could differ up to 500 ms across subjects14, biasing the identification of consistent time-frequency intervals. Thus, a smart ERDgram realignment before applying the NPCPT would facilitate brain-behavioral analyses across subjects.

The present study proposes a new pipeline, namely SmartERD, designed to disambiguate cases where multiple ERD peaks of similar amplitude emerge, which could occur in higher-order associative regions. These peaks, together with the AEP, likely represent distinct components of the brain’s oscillatory response to the same stimulus or task. In such cases, it becomes critical to establish a consistent heuristic for selecting the peak that will be used to extract temporal parameters such as latency, especially in inter-subject or group-level analyses. SmartERD automatically considers the effect of potential noise-related or intrinsic instabilities in the ERDgrams during the automatic extraction of ERD features. A basic assumption of this method is that a variance could be associated with every bin of the across-trial average TFR, and this variance propagates to the ERDgram, so that we could associate a pseudo-confidence interval with the AEP. Thus, provided that appropriate time-frequency analysis methods are used to prevent the creation of artificial peaks, SmartERD, inspired by the propagation of uncertainty on the ERD formula, uses the across-trial variance of the baseline to set a band-specific boundary for identifying local but significant extrema beyond the AEP. Among these extrema, the first peak occurring after the trigger is assumed to be the first component of the induced oscillatory response and is used as a reference peak for extracting ERD features. As the first peak is always present, it provides a stable anchor point for cross-subject comparisons. Later peaks may reflect higher-order or secondary processes, which might or might not be present depending on task complexity or subject-specific strategies. This corresponds to shifting the criterion for ERD feature extraction from the amplitude dimension (AEP) to the temporal dimension (i.e., the latency of the first peak within the band of interest). Using realistically simulated data, we demonstrate the potential benefits of SmartERD compared to the AEP. Eventually, we evaluate typical MEG recordings, benchmarking SmartERD to the standard AEP approach. Furthermore, we evaluate the advantages of pre-aligning the individual ERDgrams to the reference peak identified by SmartERD before applying NPCPT. We show that the main advantages of SmartERD are: (i) the possibility of providing a more detailed analysis of the ERD dynamics compared to the standard AEP analysis, thanks to the consideration of the AEP variance; (ii) the completely data-driven characterization of ERD dynamics; (iii) the possibility of better capturing individual differences compared to the AEP since the same response component, i.e. the earliest reliable oscillatory response, is considered for all the subjects and related to behaviour; (iv) the possibility of its use to pre-align individual ERDgrams before applying other approaches, like e.g. NPCPT, for detecting significant ERD differences across experimental conditions.

Results

ERD time-frequency patterns were estimated as time-resolved, post-trigger percentage variations of power spectrum density with respect to a baseline power density, obtained from the TFRs of MEG source activities. These were mean TFRs across trials, to reduce the variance in the single-trial estimate. In the resulting ERDgrams, multiple peaks could emerge. As long as these peaks reflect genuine modulation of oscillatory activity rather than artifact introduced by the specific TFR and parameter settings (see e.g. Figure S1 and Figure S2 showing that homologous multiple peaks appear with adaptive-width wavelet transform and multi-taper transform applied on the same data, suggesting that their emergence does not depend on the TFR approach), SmartERD identifies which of them are salient in addition to the AEP. Specifically, for each oscillatory band, SmartERD (see Fig. 5 in the Methods section) sets a pseudo-confidence interval on the AEP considering the variance of the ERD estimation, so that local ERD peaks could be identified by a peak-search algorithm, provided that they were comprised in this interval. The local peak with the smaller latency is retained as the earliest reliable oscillatory response following the trigger onset and either the related features are retained for statistical analysis, or it is used to realign subjects over time and frequency to apply statistical analyses over the whole ERD pattern. We first present results on simulations using realistic ERD patterns, then we show results obtained on real MEG data during a memory judgement task.

Realistic simulation 1: comparison between SmartERD and AEP for different noise levels

This simulation represents a possible situation where 2 ERD peaks with similar values occur and a small SNR could result in a switch of the AEP latency from the first to the second peak. We compared the SmartERD ERD peak latency and the standard AEP latency over 7 simulated datasets comprising 20 phantom participants each. In each dataset, the phantom participants were obtained by shifting in time and frequency the real TFR of a subjects comprised in the group performing the memory judgement task, after adding the TFR of a noise sequence with a selected power level (one for each dataset). The 7 different noise levels produced effects on the TFR similar to reducing the number of trials, that in some cases could cause the second peak to surpass the original AEP in amplitude, resulting in a new AEP with a different latency (see Fig. 7 in the Methods section).

Simulation 1: results. A) The TRUE ERDgram of a representative simulated subject; the asterisk marks the TRUE ERD PEAK (ERD=−66.6%, latency 1301 ms, a secondary peak with ERD=−66.1% occurs at 1605 ms). B) Plot of the average MSE on the ERD PEAK latency for SmartERD (black) and AEP (gray) at different noise levels; error bars represent the across-subjects SE. C) Sample ERDgrams of the same simulated subject for three noise levels (power 1%, 8% and 21% of the alpha power) and noise realizations switching the AEP from the first to the second peak; asterisks mark the TRUE ERD PEAK, circles mark the AEP (noise 1%: ERD=−66.2, latency = 1297 ms; noise 8%: ERD=−63.83, latency = 1601 ms; noise 21%: ERD=−59.8, latency = 1599 ms) and squares mark the SmartERD peak (noise 1%: ERD=−66.2, latency = 1297 ms; noise 8%: ERD=−63.79, latency = 1302 ms; noise 21%: ERD=−58.4, latency = 1309 ms).

Figure 1A illustrates the ERDgram of a representative simulated subject with a primary and secondary peak (ground truth-TRUE ERDgram), where the AEP is the first peak. Figure 1B shows the plot of the latency MSEs obtained by SmartERD and AEP as a function of the noise level. SmartERD MSE was in general lower than AEP, as confirmed by a paired t-test (p < 0.05), supporting its efficacy in identifying features of the first significant peak. Examples of the peak latencies extracted by AEP and SmartERD are displayed in Fig. 1C. Both approaches correctly identified the true peak at the lowest noise level. However, when increasing the noise up to levels that might induce a switch of the peaks, only the SmartERD peak latencies corresponded to the true peak. Notably, in the realizations where the noise effects did not switch the two peaks, SmartERD and AEP gave the same results. Figure S3 shows the latencies of the individual AEP, the SmartERD and the true peak for the highest noise level in all the simulated subjects. We acknowledge that this simulation is not a general case, however it allows us to understand a key takeaway. SmartERD re-references all subjects to the same response component, while AEP could correspond to different response components over subjects (See Figure S3), affecting the inter-subject comparison. Of note, the same effect of reduced consistency across subjects would occur if the ground truth AEP was the second peak and noise would sometimes switch it at the earlier peak. While in such cases the AEP might outperform SmartERD in identifying the true AEP, this is not particularly important because the AEP method might not be able to re-reference subjects to the same response component. Finally, the error on the PEAK amplitude was similar for the two approaches, possibly because of the noise-induced blurring on the small amplitude difference in the ground truth.

Realistic simulation 2: effects of intersubject variability on feature extraction

We simulated 10 datasets comprising 20 subjects in 2 experimental conditions, for 5 ERD amplitude differences (from 5% to 25%) and two noise levels (power 1% and 21% of the mean alpha power) to evaluate SmartERD in the detection of ERD differences through the analysis of the first peak latency, amplitude, working frequency. For all the amplitude differences and for all noise levels, SmartERD always identified correctly the individual peak amplitude differences, with a MSE on the peak latency 0.75 ms2 and a null error on the working frequency. Eventually, we evaluated how SmartERD could be applied before NPCPT, to pre-realign ERDgrams before the across-subjects comparison. Figure 2 shows the effect of applying SmartERD before NPCPT, comparing the real difference on the reference subject with the clusters revealed by applying NPCPT directly to the ERDgrams and their SmartERD-realigned version. Qualitatively, for all the amplitude differences, the cluster extension of the SmartERD-realigned ERDgrams was closer to the real one than the results on the not-realigned ERDgrams. Moreover, NPCPT captured the ERD differences of the main clusters better on the SmartERD-realigned than the not-realigned ERDgrams. Notably, secondary artificial clusters were obtained in the not-realigned ERDgrams, although they were not present in the original data. Figure 3 shows how the differences between the real and the SmartERD-realigned cluster extensions are considerably lower than the not-realigned ones for all amplitude differences, as confirmed by a paired t-test promoting the efficacy of SmartERD-realigned NPCPT to detect ERD differences (p < 0.05 for all comparisons).

NPCPT results. Significant NPCPT clusters for the original simulated (left panel) and the SmartERD-realigned data (right panel, referring to a 5 Hz frequency band and a 4 s time interval across the individual working frequency and first peak latency, respectively). The central panel shows the real difference for three ERD amplitude differences (5%, 10% and 15%) and noise level 1%.

Application of SmartERD to experimental MEG data

Finally, we evaluated the performance of SmartERD on the ERDgrams obtained from all 22 subjects in the experimental set. First, we compared the ERD area obtained by using the first peak extracted by SmartERD with the one extracted with the standard AEP. Then, we applied the NPCPT to detect differences across conditions (old vs. new) in the original dataset and the SmartERD-realigned data. While for realistic simulations we knew the ground truth, here, as a measure of the effect of SmartERD on the characterization of individual ERD dynamics, we evaluated the significance of the correlation between the behavioral index (item recognition performance, see subsection on the experimental data17) and the features extracted using the standard approaches (AEP or NPCPT) or SmartERD.

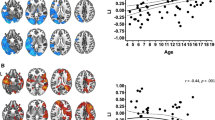

For the comparison between SmartERD and AEP in terms of their sensitivity in detecting a brain-behavioral relationship, we used the ERD area in the IntraParietal Sulcus (IPS) following the presentation of old vs. new images. Confirming17, for the alpha ERD, the old vs. new area difference was behaviorally significant with SmartERD (R = 0.55; p = 0.008, Figure S4). Conversely, the area difference obtained with AEP was not correlated with the behavioral index (R = 0.36; p = 0.10).

Real data results. (A) Group-average ERDgrams for old (left), new (middle), and the significant NPCPT clusters (right) from the original, not realigned data. (B) Same as (A) for the SmartERD-realigned data. (C) SmartERD-realigned NPCPT: statistical significance map for the correlation between old-new ERD difference and the behavioral index. (D) Scatterplot for the most significant sub-cluster. Maps in (B) and (C) display a 5 Hz band across the working frequency and a 3 s interval across the first peak latency.

Eventually, we evaluated SmartERD-realigned NPCPT and compared it with the standard NPCPT. Figure 4 shows the group-average ERDgrams for old and new conditions and the significant NPCPT clusters from the standard (Fig. 4A, four clusters) and the SmartERD-realigned data (Fig. 4B, three clusters), with different shapes and extensions. For each voxel in each cluster, we looked for a significant brain-behavior correlation for the ERD amplitude difference. For the SmartERD-realigned data only, we identified 2 sub-clusters (red clusters, Fig. 4C), showing a significant Spearman correlation between ERD amplitude differences and the behavioral index (R=−0.51 p = 0.015, Fig. 4D; and R=−0.46, p = 0.03). No voxels in the standard NPCPT clusters showed any significant brain-behavioral relationship.

Discussion

In the present study, we propose a pipeline, called SmartERD, that was designed to analyze the ERD dynamics, taking into consideration the ERD variance, due to poor SNR and high inter-trial variability. Importantly, SmartERD is useful when multiple peaks occur in the ERDgram, provided that appropriate time-frequency analysis methods to prevent the creation of artificial peaks are used. When a single ERD peak emerges in the ERDgram, SmartERD completely overlaps with AEP. In the first case, SmartERD addresses the following question: if multiple equivalent ERD peaks occur after the trigger onset, which one is selected to identify a consistent peak to analyse the temporal dynamics of the oscillatory response across individuals? SmartERD first sets a threshold to identify the peaks that are not different from the AEP and then selects the first one occurring after the trigger as representing the earliest oscillatory response, that is the first time an interruption of synchronized activity in functionally related groups of cortical neurons occurs. Later peaks may reflect higher-order or secondary processes of the investigated region. Thanks to the re-referencing to a consistent latency, SmartERD seems to better characterize individual differences in ERD dynamics compared to standard approaches (like e.g. the AEP or the standard NPCPT), as suggested by realistic simulations and experimental data. SmartERD relies on the following basic assumptions: (i) the variance on the across-trial average TFR propagates to the ERDgram, so that we could associate a pseudo-confidence interval with the AEP in each oscillatory band; (ii) a peak occurring before the AEP and within the pseudo-confidence interval is equivalent to the AEP. If one or more ERD peaks are identified within the pseudo-confidence interval, SmartERD retains the first peak occurring after the trigger onset, ensuring that we are always tracking the earliest reliable oscillatory response across subjects, which is less susceptible to inter-individual variability. As the first peak is always present, it provides a stable anchor point for cross-subject comparisons. Then, SmartERD automatically extracts for this first response a set of ERD features (working frequency, first peak latency, first peak amplitude, onset, offset, duration, area). These features can be used to assess the level of involvement and the processing time of brain regions in a particular experimental condition, to detect across-conditions differences and brain-behavior relationships. We show SmartERD performances on simulated data for different noise levels (simulating the effect of different number of trials in the estimation of the TFR) and ERD amplitude differences, and on experimental data through its sensitivity in detecting brain-behavior relationships. Given the promising results obtained with SmartERD, we suggest that this pipeline could be used as a standalone approach, or in association with other standard approaches, or for pre-aligning individual ERDgrams to a common reference peak before algorithms for statistical comparisons (e.g., NPCPT), improving their characterization of individual ERD dynamics.

Variability effects on ERD dynamics

The main, novel aspect of the SmartERD pipeline is (i) the identification of a pseudo-confidence interval considering possible contributions of intrinsic (variance of the applied TFR estimator) and extrinsic (residual artifacts or inter-trial variability) noise effects to the ERD features extraction; (ii) the identification of those peaks with an amplitude level within the pseudo-confidence interval, as peaks equivalent to the AEP; and ii) the selection, among these peaks, of the earliest peak response after the stimulus onset as a reference. We suggest that SmartERD could provide a more detailed description of the ERD dynamics and hence boost the sensitivity of the ERD analysis of individual differences. Our suggestion is supported by the results of simulations, where we used noise levels well below the inter-trial variability of the experimental data considered in this work, and by the significant brain-behavior correlations obtained by our pipeline on experimental data. Using a large number of averages to reduce variability effects on the TFR7, the standard AEP has been widely applied to extract the ERD features, like peak amplitude and latency8,9,10,11,12. However, when only small amounts of repetitions are available due to paradigm constraints or to reduce habituation effects for the subject, the large variance on the TFR could impair the statistical significance of comparisons over conditions or subjects and the sensitivity to behavioral effects. Moreover, multiple, similar peaks could occur in the ERDgram and reflect a set of processing phases especially when high-order regions are involved. Thanks to the pseudo-confidence interval associated with the AEP, an advantage of SmartERD would be the identification of these other significant ERD peaks and the selection of a reference one, i.e. the first peak tracking the earliest oscillatory response. The possibility of identifying the first significant ERD peak provides novel information on the processing sequence associated with oscillatory dynamics. We believe that, since the ERD represents an instantaneous power reduction due to a de-synchronization of the local oscillatory dynamics, the first significant peak marks the earliest stimulus-induced oscillatory response. To further illustrate this point, we show two representative subjects in Figure S2, the one used in the simulations presented in the manuscript and another subject of the same experimental set, during the “Old” condition. We used both adaptive-width wavelets and multi-taper TFR, to show that multiple ERD peaks are present in both cases (see the subsection Methodological Consideration). Notably, the peak frequencies and latencies are different across TFR approaches, but this is due to the different effective frequency resolution of the two approaches. In subj #2 three alpha-band ERD peaks are visible using both wavelet and multitaper TFRs. Notably, the AEP in this case appears at about 1 s after the earliest peak, suggesting that the AEP may correspond to a separate neural event rather than the primary oscillatory response to the task. In contrast, the first ERD peak is present and consistent across both TFR methods and more plausibly reflects the initial task-related desynchronization. In summary, we argue that the first ERD peak provides a more robust and consistent basis for characterizing ERD dynamics, particularly in studies aiming to link neural oscillations to behavior. SmartERD’s selection heuristic ensures that the same functional component is compared across subjects, which is not guaranteed when relying on the AEP, especially in the presence of multiple equivalent peaks. Notably, if the ERD variance is low, e.g. for primary areas and low residual noise or low response jitter across trials, the first peak presumably overlaps with the AEP. Conversely, when the ERD variance is large and multiple peaks occur in the ERDgram, the conventional strategy of selecting the AEP might introduce inter-subject variability: for example, in one subject, the AEP may coincide with the first ERD peak, while in another subject, it could correspond to the second or even third peak. This would negatively affect the correlation with behavior. Instead, SmartERD, by re-referencing all the ERDgrams at the same response component, likely improves the ability to detect a correlation with behavioral performance. Anyway, it is worth investigating the dynamics of the first peak to better understand its functional significance. As an example confirming the advantages of SmartERD, when analyzing correlation between behavioral performance and ERD area during recognition judgements17, we obtained significant results only with SmartERD and not with AEP (see the Results subsection Application of SmartERD to experimental MEG data). Moreover, alpha ERD latencies of the first peak were analyzed as a function of TMS stimulation, during attention re-orienting14. Significant modulations were found according to the stimulated site, suggesting a functional significance for the first peak. Furthermore, MEG recordings during a visuospatial attention task revealed that beta ERD latencies of the first peak significantly correlated with behavior5. Notably, no links between the AEP and behaviour were found in these cases, presumably because the AEP does not mark always the same response phase in a sequence, such as the first response. These results suggest that SmartERD (identifying the first peak) appears to better characterize individual differences in ERD properties. Further studies should delve into the functional significance of multiple ERD peaks.

A side result of the present work is the quantitative evaluation of TFR variance effects on ERD analysis. We believe that no studies have previously evaluated these effects on the extraction of ERD dynamic features, theoretically and with simulations. Previous studies acknowledged the presence of noise in the ERDgrams and applied different strategies to account for its effects on ERD features and improve the standard AEP extraction. As an example, to account for residual noise, several studies a priori selected a fixed threshold to define the ERD onset as the first time the ERDgram steadily decreased below that threshold13,18,19. Although SmartERD also uses a threshold for identifying the ERD peak and onset, it provides two advantages compared to the aforementioned studies. First, the individual SmartERD threshold is automatic and adaptive, as it considers individual variability. Second, SmartERD identifies a first peak different from the AEP and the related onset only when multiple equivalent peaks emerge in the ERDgram, otherwise SmartERD overlaps with the standard AEP. Notably, we acknowledge that further studies running more detailed simulations are needed to deeply understand the effect of all the contributions to the TFR variance. In this study, we applied a simple strategy to evaluate SmartERD, that is manipulate experimental data obtained from a subject by adding the TFR of controlled noise levels to the experimental TFR. We acknowledge that signal patterns different from Gaussian noise have been used in the past for simulating neurobiological signals. As an example, a biophysically principled laminar cortical model of SI to model the dynamics of the mu and beta rhythms was proposed20 and more recently an upgraded version of this model was included in a user-friendly platform21. As an alternative, a novel open-source software based on MATLAB, called SimMEEG22 has been proposed to simulate MEG/EEG evoked and oscillatory activity. However, it is important to clarify that we aim to simulate the effects of multiple contributions to the variance of the measured ERDgrams, both internal (e.g. physiological) and external. Notably, the above-mentioned tools require an optimization procedure to include external contributions, like residual noise, trial-to-trial variability, trigger jitter, etc., which is beyond the scope of this work. Thus, we adopted a simpler strategy, trying to simulate effects similar to the ones obtained when reducing the number of trials (see Fig. 7). This strategy consists in adding the TFR of Gaussian noise filtered in the same band as the physiological signals, to the TFR of the latter ones, to have effects on the ERD peaks comparable to those produced by smaller numbers of averages.

An important advantage of SmartERD is the possibility of running statistical comparisons using a limited number of trials, thanks to the pseudo-confidence interval. According to our simulations this nicely holds even when increasing the noise level, possibly corresponding to putative small numbers of trials, as suggested by the specific case shown in Fig. 1, where the latency error obtained with SmartERD increases very slowly with the noise amount, and it is considerably lower than the standard AEP, and Fig. 3, where the cluster error was tiny even for small amplitude differences at the largest noise level. Thus, the present approach might promote the application of tailored classifiers even to datasets characterized by a limited number of trials per condition.

Individual variability and its influence on ERD

A large amount of literature on ERD aimed at investigating the oscillatory mechanisms elicited by a stimulus7 or representing the neural correlate of an endogenous23 or an exogenous experimental condition, also revealed through the comparison of the ERD dynamic features over stimulus types (e.g2,24,25.

While these works looked for common features across subjects, previous studies reported the variability of oscillatory dynamics within-subject, induced by experimental conditions, and across-subjects. As an example, the inter-individual variability of ERD patterns was linked to different conditions, time periods, and frequencies during motor imagery26, which is important in Brain-Computer Interface. Furthermore, a MEG study demonstrated how alpha peak frequency differed across cognitive conditions and ROIs, both within and between subjects27. Fewer studies showed how the variability of oscillatory dynamics explained behavior, e.g., the EEG alpha ERD amplitude over the frontal-medial electrodes correlated with IQ during encoding and retrieval28. One motivation for this low number of reports might be the difficulty in properly capturing oscillatory features that encode the behaviorally-relevant inter-subject variability, especially when investigating complex cognitive tasks producing high inter-trial modulations.

In this work, we suggest that when multiple equivalent peaks occur in the ERDgram and the AEP is used, this difficulty could be partly explained by the SNR and partly to the lack of a reference latency (e.g. the first, or second or whatever oscillatory response number after the trigger onset), as it might result in comparing different underlying response components across subjects, thereby reducing statistical power and interpretability. We thus propose a strategy to take into consideration their impact ensuring that we are always tracking a consistent oscillatory response across subjects. First, we show and quantify possible effects of noise, (simulating the effect of reduced number of trials), when capturing the ERD features in an ERDgram with multiple peaks, showing that even for small noise power levels the AEP could, in some cases, deviate from the ground truth (see Fig. 1 and Figure S3). Then, we show that, for low SNR, referring individual ERDgrams to the same response phase helps to better capture the association between ERD features and behavior. In support of this statement, we previously applied a procedure similar to SmartERD in a within-subject analysis, predicting the experimental condition (shift vs. stay cue and old vs. new decision) from a particular ERD feature (i.e., the low-beta ERD duration5 or the alpha ERD area17, even from small groups of trials (down to about 10)).

Finally, we show that methods such as the NPCPT2,16 could benefit from the realignment with SmartERD, which in our simulation reduces the error between the ground truth and the estimated extension of the significant difference (Figs. 2 and 3) compared to the standard approach, and adds behavioral significance to the ERD clusters (see e.g., Fig. 4, where a significant behavioral relationship was found using SmartERD). We acknowledge that the ERD realignment, either by SmartERD or AEP, plays an important role. However, SmartERD outperforms AEP in extracting the ERD reference latency, which would also reflect on the realignment.

Methodological considerations

Being completely data-driven, an important advantage of SmartERD is its compatibility with any TFR applied, from spectrograms to multi-taper and superlets, provided that a suitable time-frequency balance is ensured to prevent the creation of artificial peaks and bolster the effectiveness of SmartERD. SmartERD relies on the concept that every voxel in the ERDgrams will always be associated with a variance independent from the specific experimental condition. Although SmartERD takes into consideration this variance, it is important that the TFR parameters are properly selected to ensure a suitable time-frequency balance in the TFR to avoid artificial peaks, since SmartERD would also consider these ones as good peaks if they are comprised within the pseudo-confidence interval. Specifically, the parameters chosen for the TFR estimator (e.g., window length, window type, or taper) determine both its bias (systematic deviation from the true value) and variance (noise added to each bin). Bias manifests as shifts or smearing of peaks in time and frequency, potentially producing small but spurious peaks, whereas variance corresponds to white noise in the TFR, which can be mitigated by averaging across trials. SmartERD is not designed to correct the estimator’s bias, while it explicitly incorporates estimator variance, since variance contributes to BAS(f) and its SE (see Eq. 7), and thus to the BOUNDARY estimated by SmartERD. We acknowledge that no TFR approach can achieve perfect resolution: some smearing in time and frequency is unavoidable, though it can be minimized. As an example, the simulations and experimental results shown in this work were obtained through continuous wavelet transform using Morlet wavelets with an adaptive number of cycles, ensuring a trade-off between temporal and spectral resolution frequencies up to the gamma band5,17. For neurophysiology data, typical width values range from 2 to 15 over frequencies between 2 Hz and 80 Hz29. Conversely, a fixed number of cycles over a large frequency bandwidth implies different time-frequency resolutions, with a decreased/increased time/frequency spanned window with frequency. Potential biases on the TFR caused by an improper choice of the wavelet width would inevitably produce a frequency-dependent noise due to smearing from neighboring frequencies that, in turn, might result in multiple artificial peaks in the ERDgrams. If these peaks lay within the SmartERD threshold, they could be detected as true peaks even producing an artificial consistency across subjects and thus representing an issue for SmartERD. Of course, a similar problem also occurs with the standard AEP. In this context, we verified that SmartERD utility is not tied to the specific TFR method applied, using multi-taper on the same data used in this work to test if multiple ERD peaks emerged also in this case. Similar to the adaptive-width wavelet TFR, one or more peaks were observed before the AEP with different multi-taper parameters (see Figure S1 and Figure S2), with SmartERD correctly identifying the first peak within the boundary. As expected, differences in temporal and frequency smoothing led to slight shifts in the location of salient peaks in the ERDgrams across the three TFR implementations. Nevertheless, the consistent appearance of multiple peaks across methods indicates that they are not spurious. Finally, an optimal strategy would be to use superlets, which are designed to solve the issue of the width selection (see simulation results in6. However, they are not rid of intrinsic variance, due to the estimator, and extrinsic, due to inter-trial variability or possible external sources. Nevertheless, superlets, wavelets with adaptive width and multi-taper would ensure the maximum efficacy of SmartERD. In summary, it is important that future users of this method explicitly report how they computed their TFR in any publication.

As a second consideration, SmartERD estimates the baseline variance in the ERDgram, where no effects of the task are present, to identify a threshold for every frequency band. In this context, we acknowledge that SmartERD does not consider the trial-to-trial variance of the baseline as physiologically relevant but as a noise effect, which is usually reduced by the across-trial averaging procedure. However, previous studies have demonstrated that, in some contexts, pre-stimulus inter-trial variability could be physiologically significant, for example, by influencing stimulus-evoked/induced activity30,31 or predicting saccadic response32 and perception of sound-induced illusion33. Therefore, SmartERD, like traditional ERD analyses based on inter-trial TFR averaging, is not suitable for the study of across-trial variability of the pre-stimulus epoch, which might provide important information, especially when ERD are analyzed and related to behavioral indices in a single-trial approach, where it is crucial to dissect the contribution of pre- and post-stimulus power to the variability of ERD34,35.

Conclusions

The present study proposes a pipeline to extract multiple features from ERDgrams while taking into consideration the variance on the TFR, representing an important tool in the analysis of individual ERD dynamics. This pipeline can also be applied to a small number of trials, representing a valid alternative, in this case, to more sophisticated machine learning approaches, requiring larger data sizes. SmartERD can also be used before statistical comparison approaches (e.g., the NPCPT), providing a multidimensional characterization of the ERD dynamics.

Materials and methods

SmartERD assumes that noise intrinsic to the TFR method or due to external sources (e.g., residual noise due to physiological artifacts) and the intrinsic across-trial variability contribute to the overall uncertainty in the estimation of the TFR. Provided that suitable time frequency analysis methods (e.g. adaptive-width wavelets, multi-taper, superlets) are used to prevent the creation of artificial peaks in the TFR, theoretical assumptions of the methods are: (i) the variance on the across-trial average TFR propagates to the ERDgram, so that we could associate a confidence interval to each value; (ii) we are not able to estimate the exact confidence interval, thus we propose a pseudo-confidence interval for the Absolute ERD peak (AEP) over the frequency band, inspired by the propagation of uncertainties; (iii) a peak with amplitude within the pseudo-confidence interval is not significantly different from the AEP; (iv) since the ERD represents the instantaneous power reduction due to a de-synchronization of the local oscillatory dynamics, a peak as in iii) marks a stimulus-induced oscillatory response, and the first peak after the trigger marks the earliest desynchronization in a group of functionally related neurons. As the first peak is always present, it provides a stable anchor point for cross-subject comparisons. An overview of the pipeline is shown in Fig. 5.

Algorithmic flowchart of SmartERD. Step 1 represents input to the pipeline. Step 2 produces a set of parameters from the ERDgram, that are the input to the core of the algorithm, Step 3. This Step estimates the BOUNDARY and identifies the first peak. Step 4 includes the two possible applications of SmartERD, to be used before NPCPT (left) or standalone (right). Step 5 produces the features for statistical analysis.

We describe SmartERD and its application to simulated and real, typical MEG datasets, comparing it with the AEP. Finally, we evaluate the effect of applying SmartERD to realign the individual ERDgrams before the NPCPT to detect ERD differences across experimental conditions.

Input data type for SmartERD

In MEG/EEG studies, across-trial average TFRs are obtained for the raw activity at the channel or source level. Then a baseline (BAS(f)) is computed as a function of frequency:

Where t1 and t2 limit the pre-trigger period including Nbas samples, typically before the trigger onset. Finally, the ERD is computed according to the well-known formula:

Figure 6 shows a typical ERDgram obtained from the mean TFR of source-level activity.

Time-frequency ERDgram and feature extraction. (A) Example of ERDgram for one simulated subject in the alpha band, where the AEP is the second peak. For the frequency bin 10 ± 1.45 Hz (based on the formula 2f/width, see equation (S1)), the power of the Nbas samples (B) and (C) the distribution of BAS(f) over 52 trials. Time is referred to the trigger onset. (D) Based on the BAS(f) variance, the adaptive threshold defines the pseudo-confidence interval on the ERDgram, where SmartERD searches for the first peak after the trigger onset at 0 s (red cross), if it does not match with the AEP (red circle). The blue cross marks the ERD offset.

Estimation of the adaptive threshold

Every voxel in the ERDgram is associated to a variance, which also depends on the number of averaged TFR. As an example, in Fig. 6B we show single-trial power time courses for the pre-trigger Nbas samples, at a selected frequency bin. In Fig. 6C we show the distribution of single-trial BAS(f) over trials. Thus, when BAS(f) is estimated from the mean TFR, its variance contributes to the error in the ERD formula, together with the variance of the post-trigger power-spectrum density time-course \(\:PSD(t,f)\). Assuming the two variables \(\:PSD(t,f)\) and \(\:BAS\left(f\right)\) as independent, as the covariance between the psd at each time sample post-trigger and the baseline was in principle negligible, the ERD standard error \(\:SE\left(ERD\right(t,f\left)\right)\:\:\)could be estimated as:

where SE is the standard error. Using the propagation of the relative error, Eq. 3 becomes:

The SE on \(\:BAS\left(f\right)\) and the post-trigger PSD could be estimated from their standard deviation across trials. Now, we are interested in evaluating \(\:SE\left(ERD({t}_{\text{A}\text{E}\text{P}},f)\right)\:\)associated with the AEP in an oscillatory band, to set a pseudo-confidence interval where searching for other ERD peaks. We thus evaluate Eq. 4 at the AEP latency. \(\:BAS\left(f\right)\) is already the average PSD over Nbas samples and its SE is lower than the AEP one and is independent from time. Conversely, the AEP might be affected by possible task-induced or behavioral variability, making the estimation of its relative error less reliable. As AEP is always lower than \(\:BAS\left(f\right)\)

From Eq. 4 a lower limit for the AEP standard error is:

Finally, to identify a threshold for the whole frequency band of interest (e.g. alpha) we retained the maximum relative error on \(\:BAS\left(f\right)\) over the band:

We acknowledge that Eq. 7 is more conservative than the standard error in Eq. 4 and we call it threshold, but in this way we prevent possible over-corrections due to large uncertainties in the estimation of \(\:\frac{SE\left(PSD\right(t,f\left)\right)}{PSD(t,f)}\) and we obtained a value independent from time.

Notably, since SmartERD uses the across-trial variance of the baseline to estimate Eq. 7, it is not suitable for the study of the physiological significance of the across-trial variability in a single-trial approach.

Finally, we acknowledge that SmartERD is designed for identifying first ERD peaks and should be modified for the analysis of ERS (event-related synchronization). In this case, the approximation in Eq. 5 is not plausible since the relative error on the post-trigger power is negligible with respect to the BAS relative error. Thus, a future dedicated study using data obtained from paradigms eliciting ERS should address the optimal adaptive threshold in the case of ERS.

Application of the adaptive threshold to feature extraction

We applied the adaptive threshold to automatically extract the first post-trigger ERD peak within a pseudo-confidence interval from the AEP, i.e. the earliest peak oscillatory response, and the related set of features that characterize the ERD dynamics (e.g., responsive frequency, peak amplitude, peak latency for the ERD peak). Usually, the ERD peak (PEAK) is identified as the absolute minimum of the ERD (AEP) over the frequency band. However, due intrinsic physiological processes, multiple peaks could appear on the ERD waveform. The amplitudes of these peaks could be similar to the AEP (see Fig. 6D), and these peaks, together with the AEP, likely represent distinct components of the brain’s oscillatory response to the same stimulus or task. Especially for low SNR, extrinsic or intrinsic power amplitude fluctuations might mask the real PEAK position or might prevent the identification of an earlier peak with a similar amplitude. Thus, selecting the AEP might result in comparing different underlying response components across subjects, thereby reducing statistical power and interpretability. Since the ERD represents an instantaneous power reduction due to a de-synchronization of the local oscillatory dynamics, we believe that the first significant peak marks the earliest stimulus-induced oscillatory response. Hence, we select the earliest response as a consistent anchor-point across subjects. In this view, using Eq. 7 for each frequency band (alpha, beta), we defined a pseudo-confidence search interval for the first local peak, using the AEP as the lower limit of the search interval, while the upper boundary was set to:

We used an automatic peak search algorithm to identify all the peaks in time and frequency for each band, select those within the pseudo-confidence interval and retain the first one after the trigger. In this way, we re-reference all the individual dynamics to the same response component, the earliest one. Notably, if the ERD pattern is smooth within the pseudo-confidence interval, the first peak overlaps with the AEP. Instead, when multiple peaks with similar amplitudes are present, the first peak and the AEP overlap only in part of the subjects. This prevents us from aligning individual responses to a consistent response latency, hampering correlation with behavior. From this first peak, we extract the following set of features: (i) the corresponding frequency bin, or working frequency, which might differ from the AEP most responsive frequency; (ii) the first peak amplitude, that is not significantly different from the AEP; (iii) the first peak latency; (iv) the onset and (v) the offset of the first peak; (vi) the difference between peak offset and onset, or duration; (vii) the area under the curve from the first peak onset to the offset, calculated with the trapezoidal method, that is a more stable measure than the peak amplitude, being proportional to the mean ERD amplitude in a time interval instead of a single time point value. For the onset/offset, we looked for the first zero crossing before/after the peak latency. Then, we assumed this zero- crossing reliable when the first peak preceding/following it was above \(\:THRE\left(ERD\left(band\right)\right)*2\:\)(Fig. 6D). Else, only if a corresponding peak was also detected at the neighboring frequencies, we still retained the zero-crossing. Otherwise, we assumed the peak as a not-significant fluctuation and looked for the next zero crossing.

An alternative strategy to estimate the area is to use the standard onset and offset instead of the features obtained with the adaptive threshold, in this case used only to estimate the working frequency and the first peak automatically.

Experimental MEG data used for test and simulations

To directly test SmartERD and to implement realistic simulations, we used a MEG dataset acquired from 22 subjects performing an item recognition task in which the amount of evidence for old vs. new decisions was manipulated across three evidence levels17. Details are reported in Supplementary Materials. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chieti and Pescara districts (#22 of December 1th 2016). The day after an encoding session (incidental task on visually presented images), MEG data were recorded by a system comprising 153 dc SQUID integrated magnetometers36,37 during a retrieval sessions (item recognition decisions on old and new images). After reconstructing the voxel activities in the source space38,39,40, the TFR was estimated using the Morlet wavelet for each trial and subject, with frequency and temporal sampling of 1 Hz and 1 ms and balanced Time-Frequency resolution, by adaptively setting the wavelet width for each frequency8,41,42 (see Supplementary Materials for a more detailed description). The resulting frequency resolution (\(\:2{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{f}}\)) ranged between 2.5 and 3.6 Hz and the temporal resolution (\(\:2{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{t}}\)) between 260 and 175 ms within the alpha band (8–15 Hz). Such a configuration reduces the likelihood of spurious peaks in single-trial TFRs. In this view, other methods such as multi-taper could also be used. The TFRs were averaged across trials of homologous experimental conditions (about 53+/−9 for each condition). Finally, Eq. 2 was applied to the average TFRs, with time interval [−400 −150] ms to evaluate BAS(f).

For simulations and tests of SmartERD on real data, we used the ERD dynamics in the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) as benchmark since we already showed a significant modulation of the alpha ERD area during visualization of old vs. new images17, consistent with the association between IPS and memory decisions reported in previous fMRI findings using a similar paradigm43,44. In addition, as expected from a region involved in item recognition decisions, in17 we obtained that the difference in ERD area was behaviorally significant, as it showed a co-variation with the inter-subject variability in item recognition performance [behavioral index: correctly identified old trials (HIT) minus incorrectly identified new trials (false alarms, FAs)].

Test on realistically simulated data

SmartERD was tested in a controlled framework consisting of realistically simulated data obtained from left IPS, to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed procedure in possible experimental conditions.

Simulation 1: evaluation of SmartERD vs. AEP for different noise amplitudes

In this simulation, we tested the performance of SmartERD to extract the dynamic features from ERD patterns for different signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) in a plausible experimental situation. Here multiple similar peaks occur in the ERDgram (as an example, the two peaks in Fig. 7). In this specific case, the addition of noise could affect the peaks similarly or cause one of these peaks to surpass the original AEP in amplitude, resulting in a new AEP with a different latency, producing three possible effects: (i) leave the AEP in its original position; (ii) change in AEP selection due to a switch of the AEP to a later peak; (iii) change in AEP selection due to a switch of the AEP to an earlier peak. In this particular simulation, the true AEP was the first one, and noise could produce the first two effects. Specifically, we first tested SmartERD in extracting the first peak latency, and we then compared the obtained results to the standard procedure based on the identification of the AEP. The opposite situation, i.e. the true ERD peak not being the first peak but sometimes shifted to become the first peak, could also occur but it is not considered here since SmartERD is designed to select always the first oscillatory response, i.e. the same response latency for all the subjects. For the simulation, we used the ERDgram in the alpha band (called TRUE ERDgram, Figure S5 panel A) from the medial left IPS in a single subject from the experimental MEG dataset. For this subject, the alpha ERD shows a double peak at 10 Hz with similar values (−67% and − 66%), with the first peak at about 851 ms being also the AEP, and the second one at about 1155 ms. Starting with the TRUE ERDgram, we created 7 datasets each comprising 20 subjects. The inter-subject differences were obtained by pseudorandomly shifting the ERDgrams in time and frequency obtaining the shifted TRUE ERDgrams (Figure S5 panel A). In each dataset, before shifting, we added the TFR of white noise filtered in the same bandwidth as the experimental data, with a fixed power for each dataset. This operation simulated datasets comprising different numbers of trials as it produced similar effects on the latencies of the ERD peaks (see Supplementary Materials, Figure S5 and Figure S6 for details). Larger noise levels simulated the effect of lower numbers of trials. As an example, in Fig. 7 we show the ERDgrams obtained from the experimental subject used in this simulation, with the total number of trials (left), with a reduced one (middle), together with the results obtained by adding the TFR of a sample sequence of filtered Gaussian noise to the original data obtained with all the trials (right). While in the original data the AEP is also the first peak (left), we show that the reduced number of averages could switch the AEP to the second peak (middle) similarly to the original data plus Gaussian noise (right). Notably, selecting different trial subsets or adding the TFR of Gaussian noise could also leave the peak ordering unchanged (see Figure S3).

Simulating different numbers of averages in the ERDgram estimation. (Left) Example of ERDgram for one simulated subject in the alpha band, where the AEP is the first peak. The ERDgram is obtained from the TFR averaged over all the 52 trials. (Middle) The ERDgram obtained from the same data as (Left), but using only a subset of 22 trials to estimate the TFR. For this trial subset, the AEP is now the second peak. (Right) The ERDgram obtained from the same data as (Left), using all the trials but adding the TFR of a filtered Gaussian noise with 16% of the baseline power. For this noise realization, the AEP is now the second peak, similarly to (Middle).

For every dataset we added a noise power level, and we used levels ranging from 1% to 21% of the mean alpha power and simulating the effects of different numbers of across-trial averages in real recordings. For the highest noise level, in the alpha band, this amplitude range corresponded to 1% of the BAS(f) standard deviation for the considered subject, for a conservative evaluation of SmartERD effects and to avoid unrealistically large noise contributions (see Supplementary Materials). Thus, if we demonstrate that SmartERD provides peaks closer to the ground truth for this conservative variability range compared to AEP, we can expect a similar or even better performances for larger variance. To simulate the 20 different subjects, for each noise level, 20 realizations of random noise with similar characteristics were generated for each activity direction and we obtained the shifted ERDgrams with noise in Figure S5 panel B. We finally extracted the features using SmartERD and compared them with the shifted TRUE values as a function of the noise level by computing the mean squared error (MSE) for the peak latency. An analogous comparison was applied to the AEP of the shifted ERDgrams with noise. The MSE obtained with the standard AEP approach and SmartERD were compared as a function of the noise level.

Simulation 2: SmartERD in the analysis of individual variability for different amplitude differences

In this second set of simulations, we tested the efficacy of SmartERD in analyzing individual dynamic features of the ERD patterns when comparing different experimental conditions. Specifically, we first validated SmartERD on the detection of ERD differences as a function of the amplitude difference, and then we evaluated the use of SmartERD before the NPCPT in the same conditions (see Supplementary Materials for details). To realistically simulate two experimental conditions, we used the ERD of the simulated subjects in Simulation 1 (condition 1) and manipulated the amplitude of the ERDgram adding a variable percentage of power modulation to the ERD, from 5% to 25% with a step of 5% (condition 2). We then simulated a dataset comprising 20 subjects by shifting the ERDgrams in time and frequency for each condition. Finally, we obtained two groups of datasets by adding the TFR of two levels of noise (1% and 21% of the mean alpha power in the stimulus interval), before shifting (see Supplementary Materials and Figure S7).

To evaluate SmartERD, we computed the differences between the first peak amplitude, working frequency, and latency extracted in the two conditions, and compared them with the corresponding TRUE differences.

Then, in the second step of the validation, we applied SmartERD before NPCPT implemented in FieldTrip16,45 that calculates a cluster-based test and its statistical significance to detect differences across conditions (see Supplementary Materials for details). SmartERD was used to realign the ERDgrams at the identified first peak latency and working frequency over conditions and subjects (realigned data), before applying the NPCPT. Specifically, we apply SmartERD to identify the first peak in the band of interest for each subject. Then, we randomly select one subject as a reference and shift the ERDgrams of the remaining subjects in both time and frequency, so that their first peaks align with that of the reference subject. Finally, we provide NPCPT with a time-frequency window defined as the intersection across all subjects. We then compared the NPCPT results obtained for the realigned and standard ERDgrams from simulation 2 by comparing the extension of the detected clusters (i.e. the total number of time-frequency pairs) with the true difference across conditions for each noise level, separately. Notably, the identified cluster extensions depend on multiple factors (e.g., the SNR, the TFR parameters, the cluster threshold)46 that have to be the same for comparing conditions, thus we compared results only across the same noise levels.

Test on real MEG data

Finally, we evaluated SmartERD performance on the ERDgrams obtained from all the 22 subjects in the experimental set by estimating correlation between the extracted features and behavior. First, in the IPS, we evaluated the area obtained by using the first peak extracted by SmartERD. We did the same with the area extracted with the standard AEP. While for the realistic simulations we knew the ground-truth, here, as a measure of SmartERD sensitivity to individual variability, we evaluated the significance of correlation between the behavioral index (see subsection on the experimental data17 and the features extracted using the standard AEP or SmartERD. Then, we applied the NPCPT to detect differences across conditions (old vs. new) in the original dataset and the SmartERD-realigned data. For the evaluation of the efficacy of SmartERD re-alignment before the NPCPT, we looked for a significant correlation between the behavioral index and the ERD amplitude difference for voxels comprised into clusters obtained by NPCPT applied to the standard and the realigned data.

Data availability

The empirical data used for this paper are available in the public repository Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17534399).

Code availability

The codes used for this paper are available on GitHub (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17534724).

References

Makeig, S. et al. Dynamic brain sources of visual evoked responses. Science 295 (5555), 690–694 (2002).

Siegel, M. et al. Neuronal synchronization along the dorsal visual pathway reflects the focus of Spatial attention. Neuron 60 (4), 709–719 (2008).

Della Penna, S. et al. Temporal dynamics of alpha and beta rhythms in human SI and SII after galvanic median nerve stimulation. A MEG study. Neuroimage 22 (4), 1438–1446 (2004).

Sebastiani, V. et al. Being an agent or an observer: different spectral dynamics revealed by MEG. Neuroimage 102 (Pt 2), 717–728 (2014).

Spadone, S. et al. Spectral signature of attentional reorienting in the human brain. Neuroimage 244, 118616 (2021).

Moca, V. V. et al. Time-frequency super-resolution with superlets. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 337 (2021).

Pfurtscheller, G. Lopes Da Silva, Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 110 (11), 1842–1857 (1999).

Spadone, S. et al. Temporal dynamics of TMS interference over preparatory alpha activity during semantic decisions. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 2372 (2017).

Babiloni, C. et al. Human cortical rhythms during visual delayed choice reaction time tasks. A high-resolution EEG study on normal aging. Behav. Brain Res. 153 (1), 261–271 (2004).

Ricci, S. et al. Aging does not affect beta modulation during reaching movements. Neural Plast. 2019, p1619290 (2019).

Nakamura, A. et al. Long-Lasting Event-Related beta synchronizations of electroencephalographic activity in response to Support-Surface perturbations during upright stance: A pilot study associating beta rebound and active monitoring in the intermittent postural control. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 660434 (2021).

Doyle, L. M. et al. Levodopa-induced modulation of subthalamic beta oscillations during self-paced movements in patients with parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21 (5), 1403–1412 (2005).

Hosni, S. M. et al. An exploration of neural dynamics of motor imagery for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neural Eng. 17 (1), 016005 (2019).

Capotosto, P. et al. Dynamics of EEG rhythms support distinct visual selection mechanisms in parietal cortex: a simultaneous transcranial magnetic stimulation and EEG study. J. Neurosci. 35 (2), 721–730 (2015).

Larson-Prior, L. J. et al. Adding dynamics to the human connectome project with MEG. Neuroimage 80, 190–201 (2013).

Maris, E. & Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 164 (1), 177–190 (2007).

Spadone, S. et al. Alpha rhythm modulations in the intraparietal sulcus reflect decision signals during item recognition. Neuroimage 258, 119345 (2022).

Leocani, L. et al. Movement Preparation is affected by tissue damage in multiple sclerosis: evidence from EEG event-related desynchronization. Clin. Neurophysiol. 116 (7), 1515–1519 (2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Response Preparation and inhibition: the role of the cortical sensorimotor beta rhythm. Neuroscience 156 (1), 238–246 (2008).

Jones, S. R. et al. Quantitative analysis and biophysically realistic neural modeling of the MEG mu rhythm: rhythmogenesis and modulation of sensory-evoked responses. J. Neurophysiol. 102 (6), 3554–3572 (2009).

Neymotin, S. A. et al. Human neocortical neurosolver (HNN), a new software tool for interpreting the cellular and network origin of human MEG/EEG data. eLife 9, e51214 (2020).

Herdman, A. T. SimMEEG software for simulating event-related MEG and EEG data with underlying functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. Methods. 350, 109017 (2021).

Yu, S., Muckschel, M. & Beste, C. Event-related synchronization/desynchronization and functional neuroanatomical regions associated with fatigue effects on cognitive flexibility. J. Neurophysiol. 126 (2), 383–397 (2021).

Meltzer, J. A. et al. Electrophysiological signatures of phonological and semantic maintenance in sentence repetition. Neuroimage 156, 302–314 (2017).

Meirovitch, Y. et al. Alpha and beta band event-related desynchronization reflects kinematic regularities. J. Neurosci. 35 (4), 1627–1637 (2015).

Wriessnegger, S. C. et al. Inter- and Intra-individual variability in brain oscillations during sports motor imagery. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 576241 (2020).

Haegens, S. et al. Inter- and intra-individual variability in alpha peak frequency. Neuroimage 92 (100), 46–55 (2014).

Capotosto, P. et al. Is there neural efficiency during the processing of visuo-spatial information in male humans? An EEG study. Behav. Brain Res. 205 (2), 468–474 (2009).

Cohen, M. X. A better way to define and describe Morlet wavelets for time-frequency analysis. Neuroimage 199, 81–86 (2019).

Krasich, K. et al. Prestimulus oscillatory brain activity interacts with evoked recurrent processing to facilitate conscious visual perception. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 22126 (2022).

Wainio-Theberge, S., Wolff, A. & Northoff, G. Dynamic relationships between spontaneous and evoked electrophysiological activity. Commun. Biol. 4 (1), 741 (2021).

Bompas, A. et al. The contribution of pre-stimulus neural oscillatory activity to spontaneous response time variability. Neuroimage 107, 34–45 (2015).

Kaiser, M. et al. Single trial prestimulus oscillations predict perception of the sound-induced flash illusion. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 5983 (2019).

Hu, L. et al. Single-trial time-frequency analysis of electrocortical signals: baseline correction and beyond. Neuroimage 84, 876–887 (2014).

Iannetti, G. D. et al. Determinants of laser-evoked EEG responses: pain perception or stimulus saliency? J. Neurophysiol. 100 (2), 815–828 (2008).

Pizzella, V. et al. SQUID systems for biomagnetic imaging. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 14 (7), R79–R114 (2001).

Della Penna, S. et al. Biomagnetic systems for clinical use. Philosophical Magazine B: Phys. Condens. Matter; Stat. Mech. Electron. Opt. Magn. Prop. 80 (5), 937–948 (2000).

Favaretto, C. et al. Multi-band MEG signatures of BOLD connectivity reorganization during visuospatial attention. Neuroimage 230, 117781 (2021).

de Pasquale, F. et al. Temporal modes of hub synchronization at rest. Neuroimage 235, 118005 (2021).

Betti, V. et al. Topology of functional connectivity and hub dynamics in the beta band as Temporal prior for natural vision in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 38 (15), 3858–3871 (2018).

Jensen, O., Hari, R. & Kaila, K. Visually evoked gamma responses in the human brain are enhanced during voluntary hyperventilation. Neuroimage 15 (3), 575–586 (2002).

Spadone, S. et al. Pre-stimulus EEG microstates correlate with anticipatory alpha desynchronization. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 182 (2020).

Sestieri, C. et al. Memory accumulation mechanisms in human cortex are independent of motor intentions. J. Neurosci. 34 (20), 6993–7006 (2014).

Guidotti, R., Tosoni, A. & Sestieri, C. Properties and Temporal dynamics of choice- and action-predictive signals during item recognition decisions. Brain Struct. Funct. 225 (7), 2271–2286 (2020).

Oostenveld, R. et al. FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 156869 (2011).

Sassenhagen, J. & Draschkow, D. Cluster-based permutation tests of MEG/EEG data do not Establish significance of effect latency or location. Psychophysiology 56 (6), e13335 (2019).

Funding

For S.Sp., S.D.P.: This work was carried out under the OXiNEMS project (www.oxinems.eu), funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Gran Agreement No. 828784. For S.D.P., S.Se.: This work was also supported by the European Union – NextGenerationEU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 - M4C2, Investment 1.5 – MIUR Call N. 3277 dated December 30, 2021, Award Number: ECS00000041, “Innovation, digitalization and sustainability for the diffused economy in Central Italy” Concession Degree No. 1057 of DATE 23.06.2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University CUP: D73C22000840006. This work was partially funded by a Bial Foundation Grant (#159–2016) of C.S. and by the “Departments of Excellence 2023–2027″ initiative of the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research for the Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Sciences (DNISC) of the University of Chieti-Pescara CUP: D57G22000370001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Sp., C.S., P.C., A.B., S.Se. and S.D.P. designed research; S.Sp. and C.S. performed research; S.Sp. and S.D.P. contributed new analytic tools; S.Sp. and S.D.P. analyzed data; S.Sp., C.S., and S.D.P. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spadone, S., Sestieri, C., Capotosto, P. et al. SmartERD: a pipeline for referencing subjects to a common peak in the analysis of ERD dynamics. Sci Rep 15, 45486 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28583-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28583-5